March 25, 2022

Air Date: March 25, 2022

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Natural Gas for Europe

/ Julie GrantView the page for this story

While the UN Secretary General warns the world not to drill for more fossil fuels, Pennsylvania gas producers are looking to expand and help supply natural gas to Europe in the face of Russia’s attack on Ukraine and tightening energy supplies. The Allegheny Front’s Julie Grant reports on these efforts and the pushback. (05:37)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s segment, Environmental Health News Editor Peter Dykstra and Host Bobby Bascomb discuss how the Deni people of the Amazon rainforest have managed to protect an important fish. Next they examine how a wastewater treatment plant in Oregon is converting the methane from raw sewage into a renewable source of electricity. And they commemorate the Exxon Valdez oil spill of 1989 and two other major events that all happened in the same week of March across different years in the town of Valdez, Alaska. (05:10)

Nuclear and Net Zero

View the page for this story

European nations are taking a fresh look at nuclear power as a more secure source of energy than fossil fuels, especially in light of the politics of Russian oil and gas. Maria Korsnick is CEO and President of the Nuclear Energy Institute and joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss why existing and new nuclear technology can help countries reach their net-zero by 2050 carbon emissions targets. (09:56)

Record Heat Wave in Antarctica

View the page for this story

During the March equinox in Antarctica, the eastern portion of the continent recorded temperatures around 70 degrees Fahrenheit higher than typical. At the same time, the Arctic also boasted higher-than-average temperatures. Climate scientist Zeke Hausfather joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss what these heat waves mean for global climate change. (10:00)

Trump’s Zombie Border Wall

View the page for this story

President Biden campaigned on a pledge to not build another foot of the wall along the US-Mexico border, but construction has recently resumed to the dismay of some ecologists. Myles Traphagen, conservation biologist and Borderlands Program Coordinator for Wildlands Network joins Host Bobby Bascomb to talk about how the construction is threatening crucial habitat in the borderlands region. (10:36)

Not Just Maple Syrup: Birch, Beech and Other Sappy Trees

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

It’s maple syrup season, but sugar maples aren’t the only sappy trees that can be tapped to make syrup. Host Bobby Bascomb visits syrup producer David Moore in New Hampshire to taste and learn about syrups made from birch, beech, walnut, and other trees. (05:13)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood and Bobby Bascomb

GUESTS: Zeke Hausfather, Maria Korsnick, Myles Traphagen

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Julie Grant

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb

With war leading to chaos in the fossil fuel markets some countries are looking to more nuclear energy, despite worries about waste.

KORSNICK: I love nuclear waste. There’s a lot of really good energy still stored in what we call nuclear waste. And I would liken it to sort of one man’s trash is another man’s treasure. And so we should store it in a way so that in the future we’ll be able to access it and reuse it.

CURWOOD: Also, construction resumes on the US Mexico border wall making it tough for migrating animals.

TRAPHAGEN: So to believe that 50 of these wildlife passageways along a span of 455 miles of border wall is going to accomplish the goal of allowing safe wildlife passage is completely absurd.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Natural Gas for Europe

Pictured above: three shale gas wells in Pennsylvania. (Photo: Jeremy Buckingham, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

As the Russian invasion of Ukraine has seen world oil and natural gas prices skyrocket, United Nations General Secretary Antonio Guterres is warning that short-term thinking about disrupted fossil fuel supplies could imperil climate safety for all of humanity. He spoke about failures to meet the Paris Climate agreement goal of limiting global temperature rises to 1.5 degrees centigrade, on March 21st at an Economist magazine forum.

GUTERRES: You have kindly invited me to speak on the topic of keeping 1.5 alive. Well, there is no kind way to put it. The 1.5 degree goal is on life support. It is in intensive care.

CURWOOD: In fact, even without the war he said we are already facing disasters.

GUTERRES: In 2020, climate disasters forced 30 million people to flee their homes three times more than those displaced by war and violence.

CURWOOD: Secretary-General Guterres begged nations not to let the quest for fossil fuels escalate into an unwinnable battle against the deadly forces of climate disruption.

GUTERRES: As major economies pursue an all of the above strategy to replace Russia and fossil fuels, short term measures might create long term fossil fuel dependence and close the window to 1.5 degrees. Countries could become so consumed by the immediate fossil fuel supply gap that they neglect or kneecap policies to cut fossil fuel use. And this is madness. Addiction to fossil fuels is mutually assured destruction.

CURWOOD: But with supply gaps created with the Russian-Ukrainian War, fossil fuel producers are already looking to expand production and infrastructure, including those fracking in the Marcellus shale region in Western Pennsylvania. Reporter Julie Grant with the Allegheny Front has more.

GRANT: Europe currently relies on Russia for as much as 40% of its natural gas supply, and that has many people worried that Russia is weaponizing its energy by reducing the flow to Ukraine and in Europe. The Pennsylvania natural gas industry wants to step in.

CALLAGHAN: We see obviously a need in Europe for more energy.

GRANT: David Callaghan is president of the Marcellus Shale Coalition, which represents gas producers in the Appalachian region.

CALLAGHAN: We have the opportunity, we have the means to help supply them with additional supplies of natural gas from the United States.

GRANT: Even before the current conflict, natural gas prices in Europe were at record highs. So US gas production has also been on the rise.

This map depicts major existing and planned natural gas pipelines, supplying Russian gas to the rest of Europe. In 2021, Russia was responsible for 45% of the European Union’s total natural gas imports. (Photo: Samuel Bailey, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 3.0)

CALLAGHAN: We've seen the rig count tick up a little bit here regionally and nationally. So yes, there is increased activity in response to those price signals, and in response to the crisis as well.

GRANT: The European natural gas market came into this winter in what Dustin Meyer, Vice President of Natural Gas Markets at the American Petroleum Institute calls a bit of a perfect storm. Europe's own gas production was in decline over the last decade. Last year, it experienced a cold winter and then a hot summer and had little energy in reserve.

MEYER: The European natural gas market, even before this conflict began, was already very, very tight. And so this conflict is really happening at the worst possible time for European gas markets. It's a reminder of just how vulnerable and exposed the European continent is to Russia and their dependency on natural gas, specifically.

GRANT: The effort to stabilize Europe's energy sources means additional export business for the US natural gas industry, according to William Ryan, Senior Advisor at the Washington based Center for Strategic and International Studies. He ran the US Export Control Program during the Clinton administration.

RYAN: For gas producers, particularly in the eastern part of the United States, it's a fairly positive outlook, long term.

GRANT: That could be good news for Pennsylvania producers, but ramping up enough production to replace Russian sources and expanding US export capabilities won't happen overnight.

RYAN: This is not like next month. You know, this is something that's going to happen over a period of years.

Climate protection advocates warn against switching out dependence on Russian fossil fuels for another country’s, and instead advocate for Europe to move towards green alternatives, like this solar park in Crimea, Ukraine. (Photo: Activ Solar, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

GRANT: Oil and Gas groups including the American Petroleum Institute and Pennsylvania's Marcellus Shale Coalition are calling on state and federal leaders to get more approvals for long term projects like pipelines and export terminals. New export capacity already in the works in Louisiana will give the US the largest natural gas export capacity in the world. But environmentalists say it doesn't make sense to invest in large scale infrastructure to support fossil fuels. Rob Altenburg is director of Penn Futures Energy Center.

ALTENBURG: They are contemplating you know hundreds of millions, if not billions of dollars of investment in new infrastructure, from pipelines to LNG export facilities, and all of this largely paid with taxpayer money. These are projects that will take years to complete and will likely never pay for themselves.

GRANT: He points out that in the wake of the Russian aggression, Germany has accelerated plans to move toward 100% renewable energy. It now intends to be free of fossil fuel use in 13 years, at which time it will no longer be clamoring for natural gas.

ALTENBURG: Companies want to build infrastructure that will lock us into this fuel use for decades. And it's not by no means clear that there'll be the markets for decades to come to allow them to do that.

GRANT: Altenburg says given climate change, the only sustainable solution for the US is to follow Europe's lead and rapidly transition to renewable energy generation.

CURWOOD: Reporter Julie Grant’s story comes to us courtesy of the Allegheny Front.

Related link:

Read more on the Allegheny Front website

[MUSIC: Billy Childs Ensemble, “American Landscape” on Lyric, by Billy Childs, Lunacy Music]

Beyond the Headlines

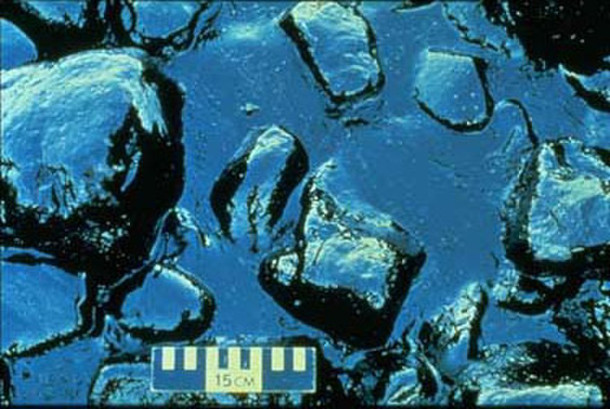

Remnants from the Exxon Valdez spilling into the rocks of beaches in the Knight Island Chain, west of Prince William Sound, three days after the oil spill. (Photo: USGov-DOC-NOAA, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

BASCOMB: Well, it's that time in the show for our trip beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peters an editor with environmental health news. That's ehn.org and daily climate.org. Hey there, Peter, what do you have for us this week?It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb

DYKSTRA: Hi, Bobby. We're gonna start out with not one but two pieces of positive news, tough to find on the environment beat but we've got'em this week. The first ones from the Amazon rainforest. There's an indigenous community of about 2000 people the Deni people who live in a so far, unspoiled part of the Amazon, no mining operations, no logging operations, turning forests into poorly performing farmland, they have lived traditionally, on a very large fish called pirarucu. They've managed to not only save, but boost their numbers over the last decade or so by taking old fashioned tradition with newfangled management techniques.

BASCOMB: Wow, that's amazing. So what are they doing?

DYKSTRA: They have outlawed, so to speak the taking of smaller fish letting the juveniles grow up and reproduce. They've protected the waters in which the pirarucu grow and thrive and are eventually fished and eaten. And they've taken a lot of steps based on some coaching from rainforest scientists to preserve the pirarucu. And perhaps most importantly, it's a protection and a culture that's being allowed to continue.

These are the Arapaima gigas, otherwise known as pirarucu, photographed in an aquarium. (Photo: Grant223, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

BASCOMB: But you know, of course, the problem in Brazil for a lot of indigenous people is having access to their land and the rights to use their land in their traditional way. But it sounds like these people have figured that out. That's right. All right. Well, what else do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: A little bit more good news from the state of Oregon, they found a way to turn some of their sewage into a potentially endless supply of renewable clean energy in Clackamas County. The sewage treatment plant operators, over the last few years, have looked up in the sky, and seen the smoke from nearby wildfires. They were concerned that if wildfires knocked out power to the sewage treatment plant, that their plant would turn into a pollution disaster for waterways in Oregon. So what they've done is they've taken techniques that are also being researched and deployed in farming operations to turn poop, partly into methane and use that as renewable energy. Methane, of course, is a major climate change gas when released into the air.

BASCOMB: Wow. Yeah, that seems like a real win win. I mean, it's renewable. As you said, we're not going to run out of sewage anytime soon. And I would think it's going to lower the electricity bills, you know, reduce methane emissions and build resilience into these systems, you know, in the face of climate change and wildfires.

DYKSTRA: I will mark your words on that, Bobby, we will not run out of poop anytime soon.

The sprawling body of water surrounded by trees is of the Willamette River located at Molalla River State Park in Oregon. During the summer of 2020 wildfires were nearing the Clackamas County’s water treatment facility, which would flood the Willamette River if the facility’s power failed. (Photo: M.O Stevens, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

BASCOMB: No, no, indeed. All right. Well, what do you have for us from the history books this week?

DYKSTRA: Here's a little Trifecta from Valdez, Alaska. Three of its most momentous events, all happened in different years. But in the same week, the last week in March, go back to 1964. There was a massive earthquake that resulted in the tsunami, the tsunami wiped out what was then a sleepy little fishing port of Valdez, Valdez had to be rebuilt, they built the town six miles away and uphill, so it wouldn't ever be wiped out again, and the sleepy little port turned into a major bustling money making port. March 27 1975 construction began on the trans Alaska Pipeline, which ended in Valdez when completed in 1977. Valdez was that oil boomtown and shipping oil out of Valdez resulted in a calamity on March 24 1989, when the Exxon Valdez ran aground spilling up to 12 million gallons of crude oil in Prince William Sound. The spill prompted the US Congress to pass the Oil Pollution Act of 1990, which requires the use of double hull tankers in US waters. But the lawsuits over the spill took 20 years to resolve. Some fishermen and others who were supposed to receive money from Exxon over the spill, about 20% of them died before the first checks were cut.

BASCOMB: Wow, that's a lot of history for one little area in the same week of March. That's that's kind of amazing that all of these things happened around the same time. All right, well, Thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News. That's ehn.org and daily climate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, Bobby, thanks a lot talk to you soon.

BASCOMB: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth website that's loe.org

Related links:

- Climate Home News | “Amazon Indigenous Community Restores Giant Freshwater Fish And Thrives”

- Reasons to be Cheerful | “Oregon Is Turning Sewage into an Endless Supply of Green Energy”

- Read more on the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill

- Learn More about Alaska’s 1964 Good Friday Earthquake

- PBS | “Alaska Pipeline Chronology”

BASCOMB: Coming up – The polar regions are warming at a shocking rate, with Antarctica recently seeing a heat wave roughly 70 degrees warmer than expected. We’ll dig into why just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org. Support also comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Billy Childs Ensemble, “American Landscape” on Lyric, by Billy Childs, Lunacy Music]

Nuclear and Net Zero

Wind turbines alongside cooling towers at the Tricastin Nuclear Power Plant in France. Nuclear power can supply a steady source of baseload power to a grid that also gets a significant amount of energy from intermittent renewables like solar and wind (Photo: Jeanne Menjoulet, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has also prompted some European nations to take a fresh look at nuclear power as a more secure and carbon-free source of energy. The Belgian government has just announced it will extend the life of two of its reactors. And French President Emmanuel Macron said "the time has come for a nuclear renaissance" when he recently announced plans to build up to 14 new nuclear reactors. Other countries are also looking anew at nuclear power, including the US where the Tennessee Valley Authority is actively pursuing advanced nuclear technology to reduce deadly air pollution from the burning of fossil fuels and to help reach net zero emissions by 2050. Here to discuss is Maria Korsnick, CEO and President of the Nuclear Energy Institute, an industry trade association. Maria, welcome to Living on Earth!

KORSNICK: Glad to be here.

CURWOOD: So how does nuclear energy fit into goals to reach net zero carbon emissions by 2050, speaking in general?

KORSNICK: Yeah, well I would say, just looking at the United States today, right, nuclear energy is 20% of our energy mix, and more than 50% of our carbon-free mix here in the United States. And I think as you look ahead to net zero, we need to get there and we need to get there affordably. And one of the things that's beautiful about a pairing of nuclear and renewables is that nuclear is there 7/24, 365, around the clock, and it pairs very well with resources that are intermittent. I think many folks are taking a look at, what does it really take to decarbonize, what does that picture really look like? And I think you've seen that in France; just a few years ago, you would hear France talking about slowing down, if you will, from nuclear. So this is a very significant announcement on their part that they are looking forward at growing their fleet. We've seen a lot of interest from Poland, we've seen a lot of interest from Romania, we have done trade missions down to Brazil. Canada just announced in December that they've selected something that they want built, it's American technology that they want built by 2028. So a lot of interest right now in nuclear for its carbon-free future.

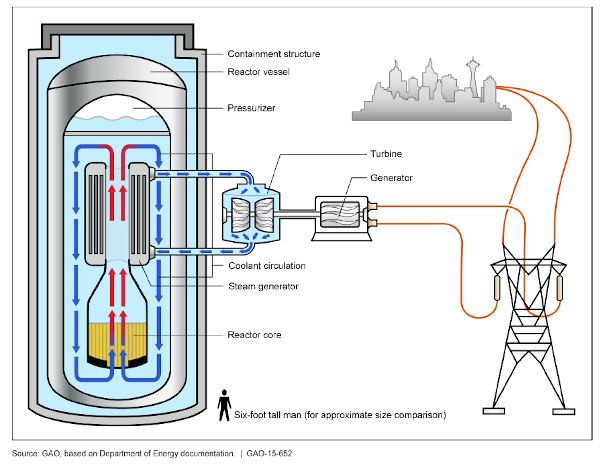

Illustration of a light water small modular reactor (Image: U.S. Government Accountability Office, public domain)

CURWOOD: Some criticize nuclear power as being very expensive. Power stations take a long time to build, the tab seems to get higher and higher, and especially vis-a-vis renewable energy it's just many orders more expensive than renewable. And your response?

KORSNICK: Well, I think you have to really take a look at the entire value proposition. And yes, there are examples of nuclear being expensive. You know, we did a recent study looking at the Pacific Northwest Area, company Energy Northwest, specifically. The governor there in the state of Washington said, Let's go carbon free, and let's go carbon free by 2045. And so they took a look, let's do that all with renewables. And then they said, All right, well, let's do it with some renewables and let's do it with some small modular reactors. And adding those small modular reactors saved the customers $8 billion a year. And so again, it's that combination of that always-there electricity, carbon-free, paired with those intermittent renewables, that at the end of the day, is the most affordable solution for customers.

CURWOOD: So there's a lot of talk about small modular reactors, whether it's the pebble bed that the Germans developed and the South Africans tried, and I think the Chinese are doing, and now the TVA is talking about small modular reactors. What are they, and how would they be both safer and more cost effective than the big units? What's the advantage of these smaller reactors?

KORSNICK: Yeah, I would almost wish that we didn't name them small modular reactors, I wish we would have named them simple modular reactors. Because what's really different about them is their simplicity. And the simplicity in the design allows for much less than what you have in the large ones, so not just much less in size, but you need fewer systems, for example, some of the systems are passive, so they don't need active components. So it's the simplicity in the design that allows for these things to be made in, say, in a factory setting. And so you're not sort of building it, almost think about a house, you're not sort of stick building your house from scratch, but that you're getting the sort of modular compartment that you can then bring to the site and set up. So the simplicity and the manufacturing of these designs is really what's making them different. And, you know, a prime place to build a nuclear plant could in fact be where there's a coal plant today that needs to be shut down, for reasons that they want to retire it. The small modular reactors, those are more the size of a coal plant. It's very attractive to build a carbon free source there, that also produces a lot of megawatts, maybe similar to a coal plant, it's a very attractive place for small modular reactors.

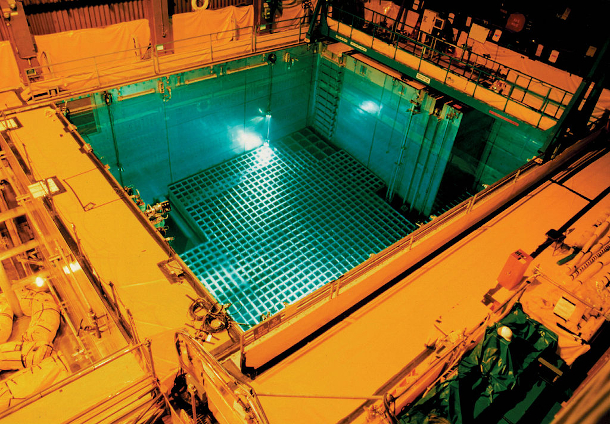

The spent fuel pool containing nuclear waste at the San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station in California, which was taken offline in 2013. Nuclear “waste” contains more than 90% of the potential energy of the original material, according to the U.S. Department of Energy. (Photo: Nuclear Regulatory Commission, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Simple but safe as well? To what extent does this approach sacrifice safety?

KORSNICK: Oh, not at all. No, these are actually even safer, and I say that because the plants we have today are also very safe. But this passive design actually relies even less on individual action or operator action.

CURWOOD: Impossible to melt down, the way say a pebble bed reactor is apparently impossible to melt down?

KORSNICK: Yes, I would say some of these designs are -- we would use a different term, we call it "walk-away" safe, but yeah, you could walk away and it stays safe.

CURWOOD: What's the view of the Nuclear Energy Institute and your own about nuclear waste? Most of the time when this discussion comes up, people say oh, yeah, okay, carbon free, but what about all that nuclear waste that remains hot, remains radioactive for thousands of years. And if you reuse it, the way the French do with breeder reactors, then you get plutonium and you could get weapons. In other words, people think that this stuff is really pretty dirty. And we don't really have great places to put it or good ways to reuse it. What do you say?

KORSNICK: Yeah, it's interesting. I know waste can be a very controversial issue. And I would be a bit provocative, perhaps, to say, I love nuclear waste. And what do I mean by that? There's a lot of really good energy still stored in what we call nuclear "waste." And I would liken it to sort of one man's trash is another man's treasure. I think the best thing that we could do is appreciate a lot of the different components that are in that thing we call waste, that in the future, our grandkids and their grandkids, they're going to want to be able to reuse this. And so we should treat it as we do today, in a very safe way, we should store it in a way that in the future, when we want to, we'll be able to access it and reuse it, whether we're reusing it in another reactor, or we're reusing it for medical needs. And so again, I look at it more as a resource for the future.

CURWOOD: Tell us what you make of what the Biden administration has proposed for the nuclear industry. I know there were some provisions in what was known as the Build Back Better bill, who knows what's gonna happen with that budget reconciliation, but what do you think of what they were talking about?

KORSNICK: Yeah, first, I'd start with the bipartisan infrastructure bill, because that did pass. And there were many very positive provisions in there for nuclear power. One very important one is the Advanced Reactor Demonstration Project, ARDP, which is funding two new-style plants. And it fully funded that program out for several years, that was to the tune of two and a half billion dollars, so very significant. And that's a public-private partnership, if you will, that will bring two new designs online before the end of this decade. They also had $6 billion in their for a civil nuclear credit program to help financially support reactors that are at risk of closing. So a really strong vote of support, I would say in that bipartisan infrastructure package. Now, the Build Back Better package obviously has not passed, and we all can have different opinions of what its success may be, but built into the Build Back Better plan are some production tax credits for nuclear power and the current operating fleet that would really level the playing field for nuclear across the board.

Maria Korsnick is the CEO and President of the Nuclear Energy Institute, an industry trade association. (Photo: Courtesy of Nuclear Energy Institute)

CURWOOD: Right now, oil and gas prices are sky high, you know, you've got Russia's invasion of Ukraine and Europe is acutely feeling the risks of dependence on Russian hydrocarbons, particularly gas. How do you think this volatility is influencing the conversation around nuclear energy right now?

KORSNICK: Yeah, I mean, it's for an unfortunate reason. And my heart goes out to the Ukrainians and everything that they're going through. But it's a stark reminder of paying attention to who you're doing business with. And the reality is, Russia is also in the market to sell reactors. And Russia is very much interested in doing business with lots of different countries. And why is that? Because they want to control your energy supply. And this is a case where we are very interested in ensuring that the strength of American technology, American operating experience, we operate plants the best in the world, and we want to share that experience and our technology and help others meet their carbon-free pledges. When you do business on nuclear power, you form 100-year relationships. You're gonna design it, you're gonna build it, you're gonna operate it for 60 to 80 years, you're gonna decommission it. And it's because of that long term relationship and the value that we place on it and our value for non-proliferation that we should want countries to do business with the United States, and not with state-owned enterprises.

CURWOOD: Maria Korsnick is the CEO and President of the Nuclear Energy Institute. Maria, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

KORSNICK: Thanks, enjoyed it.

Related links:

- About Advanced Small Modular Reactors from the US Department of Energy

- Video: Small Modular Reactors Explained – Nuclear Power’s Future?

- About Maria Korsnick

- CNN | France announces plans to build up to 14 nuclear reactors

- Tech Explore | Belgium delays nuclear energy exit 10 years due to Ukraine war

- Listen to LOE’s recent interview about how “future thinking” is guiding safe storage of nuclear waste

[MUSIC: Schwey, “Sh'qweyla” on Schwey, 604 Records]

Record Heat Wave in Antarctica

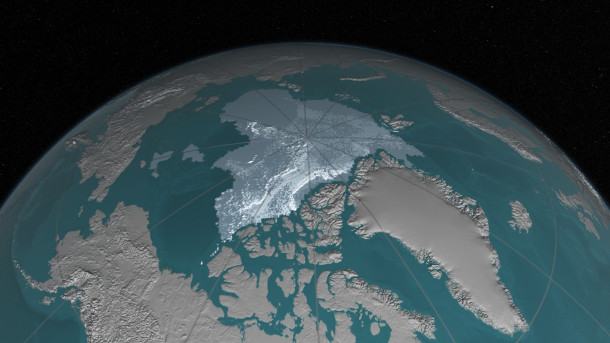

Around the March Equinox in 2022, parts of Antarctica were seeing temperatures spike to nearly 70 degrees Fahrenheit hotter than average. (Photo: Christopher Michel, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: March 20th marked the most recent equinox. That’s when the sun appears to be directly above the equator and shines equally on both polar regions. But this time both the Far North and Far South also shared some record heat waves. As summer was ending in the Antarctic, some weather stations there recorded several days at 10 degrees Fahrenheit. Now that might seem quite cold to us, but it’s a whopping 70 degrees warmer than seasonal norms, and a huge surprise to scientists. And at the same time portions of the Arctic had some days that were more than 50 degrees warmer than usual, though far Northern heat waves are not as uncommon these days as this recent far Southern one. To find out what might be going on, we called up Zeke Hausfather, a climate scientist and climate research lead at Stripe Climate. His company is looking at ways to finance and build systems intended to remove massive amounts of carbon from the atmosphere and thereby reduce the impact of global warming. He’s on the line now from Oakland California. Zeke, welcome back to Living on Earth!

HAUSFATHER: Thank you. It's great to be here.

CURWOOD: So tell me what do climate scientists and meteorologists think is happening in Antarctica to start up this specific heat wave.

HAUSFATHER: So what's happening in Antarctica is, to be honest, mind boggling for us, you know, it's 70 degrees Fahrenheit hotter than it should be for this time of year in parts of eastern Antarctica, which is really unprecedented. We've never seen anything like this in the 70 years of data we have from that region. We're working, as we speak, to figure out, you know, what role climate change played in this, how much more likely this sort of heat wave was made by the warming that we've experienced there in the world? And we know that, you know, warming has certainly contributed to these sort of extreme heat events, but exactly how much is something we're gonna be figuring out using both the data we've collected over the years and our climate models.

CURWOOD: Now, the southern hemisphere has a lot of heat problems in Australia. Any relationship, do you think, to what's going on in Antarctica?

HAUSFATHER: So certainly, both are being exacerbated by a common cause, which is the the warming of the planet, you know, we've seen around the world, these sort of extreme heat events becoming more common. Another great example is what we saw in the Pacific Northwest this past summer, you know, we had 116 degree temperatures in Portland, 121 degree Fahrenheit temperatures in Canada. And we actually took a look, we being climate scientists took a look after that event. And what we found was quite interesting, you know, it was still an extremely rare event, a maybe one-in-1000 year event. But without climate change, it would have been a one-in-150,000 year event, so already has been made 150 times more likely. And if the world warms by two degrees Centigrade, about four degrees Fahrenheit, by the end of the century, which we're on track to warm more than that today, it would become a one-in-20 year event. And so that teaches us that, you know, this larger global warming can have a disproportionate impact on the likelihood of these sort of extreme heat events.

????Heat wave in Antarctica, +38 °C (+68 °F) above normal.

— Dr. Robert Rohde (@RARohde) March 21, 2022

That's not an error, or a typo.

The remote research station at Dome C recorded a temperature nearly 40 °C above normal for this time of year, beating the previous March record by a startling 20 °C. pic.twitter.com/HkzydQyQ7A

CURWOOD: To what extent, is there's some sort of atmospheric river bringing water vapor down into Antarctica from places that usually doesn't get it?

HAUSFATHER: So, any extreme heat event is going to have meteorological conditions or weather patterns that are driving it. And so in this case, what seems to have happened is there was an atmospheric river that brought a lot of moisture over East Antarctica. And that moisture carried a lot of heat with it. And so that drove these extreme temperatures we've been seeing in the region. Or relatively extreme, I should say, it's still below zero, but it's not negative 70. And so that, you know, there was a direct cause of that. But that sort of event, you know, has not happened in the past, you know, we have nothing similar to it in the seventy year record we have for that region.

CURWOOD: So this particular heatwave in Antarctica, how fair is it to attribute this to global climate change that humans are involved in?

HAUSFATHER: So we know that climate change has made Antarctica warmer than it was a century ago. You know, Antarctic is actually a fairly complicated place when it comes to the climate, in part, because there's really two factors going on. One is greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, which are warming the region. But at the same time, the ozone hole that we created through emissions of chlorofluorocarbons back in the, you know, 60s 70s, and 80s, has actually led to a lot of cooling in that region relative to what would have happened if we hadn't emitted those. And so because of that Antarctic has warmed more slowly than the Arctic. You know, that being said, it's still warmed enough that there's probably, you know, an influence in terms of the likelihood of the sort of extreme heat event. It's not warming as fast as the Arctic, which is warming about three to four times faster than the rest of the world, in part because one of the big drivers of Arctic heating is what we call albedo, or reflectivity changes. So as you melt sea ice, you melt snow, you expose dark surfaces underneath, those dark surfaces absorb much more of the sun's heat, and reflect much less back to space, Antarctica is a bit more resilient for that, in part, because so much of the continent is covered by mile thick ice sheets that you need a lot of melting to expose darker surfaces. So in part, because of that, we haven't seen quite the degree of amplification of global warming in Antarctica, as we've seen in the Arctic, there's also the possibility and this is an area where, you know, it's a little harder for us to be sure about, that climate change is changing weather patterns in a way that might make this sort of event more likely. But again, until we have time to, you know, do research on this, do attributional studies of this, it's, we can't say with confidence today exactly how much more likely climate change made this sort of extreme heat.

Scientists have estimated that the Arctic Circle is warming from 2-4 times as fast as the rest of the world, causing permafrost to thaw at a rapid rate, impacting infrastructure and people’s livelihoods. (Photo: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Tell me, how does climate modeling work when it comes to figuring out possible extreme weather events?

HAUSFATHER: Sure. So you know, what we saw in Antarctica is an interesting example, right? It's so far outside anything that we've observed in that region, that we can't easily use the historical temperature record there to figure out, you know, what are the odds of this sort of event. And so for that climate models are actually really useful. And in particular, a fairly new development in the climate modeling world called large ensembles are really useful. And the idea behind large ensembles is you take a state of the art sort of supercomputer climate model, and you run the same model, say 50 different times. But each time you start it up slightly differently. Of a butterfly flap its wings in Brazil, so to speak. And that leads to you know, different chaotic weather patterns in each of those model runs. And so you can look across, say 50 different versions of the world with slightly different weather and say, do we see anything like what we saw this past week in Antarctica in any of those models. And it turns out some initial work being done by Flavio Lehner at the National Center for Atmospheric Research shows that we do. There is a particular member of that ensemble that has a sort of crazy extreme heat spike in 2018 in that model run. That’s similar to what we saw in the real world in 2022. And so we can look at that and say, okay, given these 50 versions of the real world we see this one time, what does that tell us about the odds of this event? And then what we can do, which is really cool, is we can sort of say, okay, let's go back in time in those models to say, or the 1800s in general and say, okay, in the climate of the 1800s? How likely would this event have been? And we can look at the difference between that likelihood to get some sense of how much more likely climate change has made these sort of extremes. So a really cool way to use climate models to sort of study how the variability of weather and the likelihood of extreme heat events has changed.

Antarctica is not warming as fast as the Arctic, in part because of a feedback loop in the Arctic, where the thinner ice melting faster reveals dark open water, which absorbs sunlight and traps more heat. In contrast, Antarctica has much thicker ice sheets, so most of the melting has yet to reveal the dark open water. (Photo: Jeremy Potter, NOAA/OAR/OER, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Okay, I'm sitting down. Now, Zeke, just tell me what sorts of predictions are the climate models showing us now in terms of extreme weather events going forward?

HAUSFATHER: So it really depends on what we do. If we can bring our emissions down to zero, the Earth will stop warming, we're still going to be stuck with the warming we've had so far, at least unless we're removing carbon from the atmosphere. But we can ultimately control how much warming we have. That said, the world today seems on track under current policies for about three degrees warming, by the end of the century, three degrees centigrade. So about five, five and a half degrees Fahrenheit, that could be much higher, if we end up getting unlucky with what we call feedbacks in the climate system, or could be a little lower if we end up getting lucky, but it's still a very scary future. You know, one of much more extreme heat events, more extreme wildfires, sea level rise, many of the world's species going extinct because the temperature ranges they live in are shifting faster than they can move, impacts in agriculture. You know, they're sort of a parade of horribles so to speak, that would happen in that world. But the good news is, we can change that, you know, we still have time to reduce our emissions. And if we get our emissions globally to zero, in the latter half of the century, we could still limit warming to well below two degrees, which is what countries agreed to under the Paris Agreement back in 2015.

CURWOOD: So, Zeke, you're a scientist, but I'm going to ask you a political question. Right now, with the war in Ukraine, and with the boycott of Russian oil, there's a lot of talk of building out more fossil fuel infrastructure. How advisable do you think it is that we should add more infrastructure for fossil fuels to meet the problems that have been caused by this unprovoked attack on another nation by the President of Russia?

Zeke Hausfather is a climate scientist and Climate Research Lead at Stripe. (Photo: Courtesy of Zeke Hausfather)

HAUSFATHER: It's a tough question. I think we need to be very careful about locking in further dependence on fossil fuels, given the challenges of climate change, and the big impacts it's going to have on the world. You know, at the same time, high fuel prices fall mostly on the poor. Lower income people spend much more of their paychecks on transportation, they tend to have older, less efficient cars. And so I think we need to target our climate policies in a way that really helps the poorest people. You know, electric vehicles are great, it's great, they've been getting a lot cheaper, as someone who drives an electric vehicle, you know, I don't pay that high cost of the pump. But electric vehicles are new cars, and most people who are lower income, don't buy new cars, they can't afford to. And so having ways to give relief to those people in the short term, I think is important to consider. At the same time, we need to make sure that any additional oil and gas infrastructure we build, you know, is built with a view toward eventually getting off it. You know, if we're building liquefied natural gas terminals to bring more gas to Europe, we should make sure that those could also support liquefied hydrogen for a future green hydrogen economy. You know, we need to make sure that pipelines we're building to transport natural gas, say from the Middle East or from Africa to Europe could potentially take CO2 in the future to places to sequester and underground you know, any of the future fossil fuel infrastructure we build we need to build with an eye toward repurposing it for the clean energy economy in the future.

CURWOOD: Zeke Hausfather is the Climate Research Leader at Stripe. Zeke, thanks for taking this time with me today.

HAUSFATHER: No worries. It's great to chat.

Related links:

- The Washington Post | “It’s 70 Degrees Warmer Than Normal in Eastern Antarctica. Scientists Are Flabbergasted.”

- NBC News | “Antarctica, Arctic Undergo Simultaneous Freakish Extreme Heat”

- About Zeke Hausfather’s company, Stripe Climate

- About Zeke Hausfather

[MUSIC: T-Bone Walker, “Mean Old World” on T-Bone Blues, Atlantic Recording Corp.]

CURWOOD: Coming up – Wall construction has resumed along the US Mexico border, raising concerns for migrating species. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining a passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Joshua Redman “Floppy Diss” on RoundAgain 9feat. Brad Mehldau, Christian McBride, Brian Blade), Nonesuch Records Inc.]

Trump’s Zombie Border Wall

The “heartland of North America,” where Neotropical and temperate zones meet at the US-Mexico border, is home to animals like the American pronghorn (Antilocarpa americana). (Photo: Myles Traphagen, Wildlands Network)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

The Trump administration spent roughly 15 billion dollars to build some 455 miles of wall along the US border with Mexico. President Biden campaigned on a pledge to end construction and vowed to not build another foot of the wall. But construction has recently resumed to the dismay of many ecologists in the region.

[SFX BIRD SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: Far from the barren desert one might think of, much of the borderlands are teeming with biodiversity.

[SFX BIRD SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: Myles Traphagen is a conservation biologist and Borderlands Program Coordinator for Wildlands Network. He notes the US Mexico border is a crucial habitat for countless iconic species.

TRAPHAGEN: It's actually one of the most rich biodiverse places on the North American continent. You know, when I hear the term Borderlands, I'm thinking less that it's the border, but rather it's the heartland of North America. And what makes this area unique is that it's the meeting ground of the Neotropics and the temperate zones. So what that means in layman's terms is that Southern species such as the Jaguar and the ocelot and the javelina, and the coatimundi, they all reach their northern limits in this part of the world. And then iconic North American temperate species such as the black bear, they reach their southern limit. So in this region, you have this merging of these different biotic communities. And that's what makes this area extremely biodiverse.

BASCOMB: Well, on the campaign trail, President Biden said he would not build another foot of the wall once he was elected. To what degree has he kept that pledge?

With only four inch gaps in between the steel bollards, these thirty foot “pedestrian fences” in Arizona, New Mexico, and California only allow for very small animals to pass through. (Photo: Myles Traphagen, Wildlands Network)

TRAPHAGEN: Well, it was looking pretty good for about a year. And fairly recently, they began border wall construction in South Texas in the McAllen area. And this is sort of undercover of levee construction, because you know, they have flood zones down there. But um, you know, from all accounts, the levees were intact, and there were no existing problems with them. And so now they're building concrete levee walls. And compared to the steel bollard walls that we have here in Arizona, California and New Mexico, a concrete levee wall is about the most extreme impermeable barrier you could apply to impeding wildlife movement. Not much can really pass through the steel bollards here. These are 30 feet tall. And they have six inch steel bollards, which are essentially six inch diameter, cold rolled steel. In between each one of these beams is a four inch gap. So nothing larger than a skull size of four inches would be able to pass through there. Maybe a Cottontail rabbit could fit through, lizards and snakes and things like that. But when you have a concrete wall, you know, nothing can pass through that. So it's really unfortunate that they have started that construction. And then recently, they just announced last month that they are going to be filling in the gaps that were not completed here in Arizona, New Mexico, and California. And the really difficult part of this is that these existing gaps are acting as wildlife corridors. They facilitate movement. And if you go down to the border and visit these locations, you see so many tracts of deer, Javelina, mountain lions, all passing through these small gaps, which may be you know, ranging from two meters to thirty meters wide. So if they fill in these gaps, that's really gonna be devastating for wildlife in the region, because they will no longer be able to migrate back and forth in their ancestral homes. In an arid region like this water sources are few and far between and they change seasonally. So generations of animals have been born into places where they've learned the terrain, and where to go throughout the season. And now we've cut that off and altered that ecological process in a matter of two years time.

BASCOMB: Yeah, it's hard to adapt to something like that. Well, why are these gaps there to begin with, and why now the need to fill them in?

TRAPHAGEN: Well, the construction crews were working towards each other, that seemed to be a strategy is to divide up the crews and see who could build fastest. And so some of these meeting grounds, they had not matched up things perfectly. The engineering, you know, was not done very well. In other cases, they hadn't figured out how to deal with the hydrological engineering. So essentially, they were making it up as they were going along. So a lot of these places were just left there, and they assume that they would just go back and figure it out. And so that's what's gonna happen now is that they're gonna go back and basically fix what they didn't have a good design for to begin with.

BASCOMB: But I mean, President Biden said he wasn't going to build another foot of the border wall, and it sounds like this is many, many feet, you know, two meters at six feet at a minimum for some of these gaps.

This family of javelina, also known as collared peccary (Pecari tajacu) in the Sonoran Desert of Pima County, Arizona, are among those animals that are prevented from traveling to historic water sites due to border wall construction. (Photo: Myles Traphagen, Wildlands Network)

TRAPHAGEN: It is. And you could take one location and say Okay, we're going to add five miles of border wall in a location that may not be as critical to wildlife as one location. And so some of these places where there might just be, you know, a two, three, four meter gap in the wall is weighted a lot more heavily, because it occurs in a place that's really crucial to wildlife migration.

BASCOMB: Well, from what I understand, at the end of 2021, the Customs and Border Protection authorized funds for working along the border, and you know, that we've already talked about filling in these gaps, but that work is also supposed to include things like cleaning up abandoned construction sites and repairing erosion. Can you tell us more about that?

TRAPHAGEN: Okay, so the remediation plan. The plan basically, is to support the border wall infrastructure, and that includes the patrol road, cattle guards, fences, and making sure that places don't erode and undercut the border wall, but none of it is really addressing the environmental concerns. They say that they are going to provide wildlife passageways along these some stretches of border wall. And when I first read it, they said it was eight by eleven. And I thought, okay, you know, eight feet by eleven, that'd be great. But no, it turns out, it was eight by eleven inches. So you're talking the size of a piece of paper and smaller than the standard doggie door you would buy at PetSmart. So to believe that 50 of these wildlife passageways along a span of 455 miles of border wall is going to accomplish the goal of allowing safe wildlife passage is completely absurd.

Mountaintop removal in the Coronado National Forest in Arizona has drastically altered the natural landscape and devastated unique ecosystems. (Photo: Myles Traphagen, Wildlands Network)

BASCOMB: Now, the Trump administration used the REAL ID Act of 2005. And that allowed them to basically move forward with wall construction in a way that ignored dozens of environmental laws. Can you tell us more about that, please, and to what degree is President Biden still leaning on the REAL ID Act to continue the work there?

TRAPHAGEN: Well, the REAL ID Act is unique in American legislation. So they enacted this in 2005. And there's a provision that allows the Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security to waive all laws for the construction of border barriers. And there's been upwards of around 60 laws waived for border wall construction. This includes the National Environmental Policy Act known as NEPA, the Endangered Species Act, the Safe Water Act, the Wilderness Act, the native Graves Protection Act, Bald Eagle Protection Act, I mean, the list goes on.

BASCOMB: And we talked earlier about the Biden administration constructing you know, these new levees and filling in the gaps in the wall. Is the REAL ID Act still in place? Is that what they're relying on? Or is it no longer applicable?

Mountain lions in the San Bernardino National Wildlife Refuge are too large to pass through the pedestrian fences erected along the Southern border. (Photo: Myles Traphagen, Wildlands Network)

TRAPHAGEN: Unfortunately, the waivers are still in place. And so for each segment of a border wall project, a waiver is issued in the Federal Register. We were hoping that the waivers would be rescinded. But they have not been. They still have the ability to go in there and do whatever they want without having any congressional oversight with having no environmental impact studies done. And that's just simply unacceptable in the American system of government, where we have been a world leader in conservation and careful review of how we treat our land and how we implement public works projects.

BASCOMB: Well, President Biden has said that he won't actually tear down the wall that was built in the previous administration. And as we talked about, he's actually filling in some gaps. But what do you think at this point should be done to mitigate the damage to wildlife?

TRAPHAGEN: Well, we need to convert these walls to vehicle barriers. There's a couple different types, and the one that's the most well known is called the Normandy barrier. And those are basically those x's constructed of, they used old railroad tracks. That still allows animals to pass through because there's sufficient gap size underneath them, for animals to get through. In fact, just a couple of weeks ago, I was down on the border in New Mexico, and a big mule deer, you know, was going down the road and I observed it jump right over the border, the Normandy barrier, that was there. That is a fundamentally different structure in terms of how it affects the environment than the 30 foot walls. And in fact, not only do they not allow wildlife to pass through, they also are really dangerous to people who are attempting to cross these fences. So these border walls are killing machines on every level and in a humane and just society, we can't allow this to go on.

Vehicle barriers, which have larger gaps than pedestrian fences and concrete levees, may allow more animals to migrate successfully along the border. (Photo: Myles Traphagen, Wildlands Network)

BASCOMB: Myles Traphagen is a conservation biologist and Borderlands Program Coordinator at Wildlands Network. Myles, thank you so much for your time today.

TRAPHAGEN: Thank you so much, Bobby, and I really appreciate that Living on Earth has taken an interest in this important topic.

BASCOMB: We reached out to US Customs and Border Protection and a spokesperson replied via email. “During the environmental planning process for (the) border barrier, CBP coordinated closely with the Department of Interior (DOI) and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) to identify potential impacts to wildlife and approaches that support both wildlife migration and border security to the greatest extent possible.” To read their full statement visit the Living on Earth website loe dot org.

Full US Customs and Border Protection statement by a CBP spokesperson

"During the environmental planning process for border barrier, CBP coordinated closely with the Department of Interior (DOI) and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) to identify potential impacts to wildlife and approaches that support both wildlife migration and border security to the greatest extent possible.

These elements include the installation of small wildlife passages and opening of flood gates. CBP has been actively engaged with its interagency partners, including various bureaus of the Department of the Interior and the Department of Agriculture, regarding the development of potential long-term environmental mitigation measures to include wildlife use and movement studies."

Related links:

- Wildlands Network | “The Border Wall in Arizona and New Mexico–July 2021”

- Living on Earth | “How the Border Wall Could Harm Wildlife”

- Living on Earth | “Science at Risk at the Border”

- Living on Earth | “The Border Wall’s Wildlife Impacts”

- Living on Earth | “Exploring the Parks: Cactus and Snow in the Desert Sky Islands”

- The Washington Post | “Where Trump’s border walls left deep scars and open gaps, Biden plans repair job”

[MUSIC: Old West Trio, “My Rifle, My Pony, And Me” on Hoofin’ It, Old Wes Trio]

Not Just Maple Syrup: Birch, Beech and Other Sappy Trees

Maple syrup is classified into different grades. A darker syrup indicates a stronger flavor. (Photo: LexnGer, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

BASCOMB: These warm days and cold nights of spring mean it’s maple syrup season in much of the northeast. And like the crocuses that pop up through the cold spring soil, sap buckets start to appear on maple trees across the region. But not all syrup comes from maples, as one tree farmer in New Hampshire showed me.

[WALKING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: David Moore leads the way down a wide dirt path on his farm in Lee, New Hampshire. The path is lined on either side by stone walls built by farmers more than 200 years ago in the typical New England style. Those farmers were likely tapping maple trees this time of year. A skill no doubt learned from Native Americans in the region who have a long tradition with maple syrup. But David Moore is turning centuries of syrup making on its head.

MOORE: So, I have five beech trees tapped here. American beech. You need a vacuum pump to extract sap. Maple and birch, the sap will come out of the tree without a vacuum but other species you need a vacuum.

BASCOMB: Light blue plastic tubes jut out from each of the 5 beech trees in this stand. Another tube runs through a vacuum pump covered by an inverted plastic bin and into a plastic bucket.

[OPENING BUCKET SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: David takes the top off the bucket. Inside, a couple inches of frozen beech sap.

MOORE: Maybe one gallon or so. So this is about what I've been getting from these trees.

BASCOMB: David tells me he had a lot more luck tapping a different set of beech trees last year and got a lot more sap. Still, he’ll need something like 200 gallons of beech sap to get one gallon of syrup. The sugar content for good old maple syrup is far more concentrated. So it takes just 40 gallons of maple sap to make a gallon of syrup.

MOORE: So nothing will replace maples. But it'll certainly add some value to your operation if you can do it.

BASCOMB: And that is David’s goal here. For his PhD work at the University of New Hampshire, he wants to figure out the best trees, other than maple, to tap and make syrup. It could be useful information for maple syrup producers in the region. They could use their existing equipment to tap other kinds of trees on their land and make more money.

MOORE: Just getting a little more value out of your woods and especially with beech. Beech around here is thought to be just a really weedy kind of a nuisance species. And so if there's a good use for it, then… yeah, just good for the producer.

BASCOMB: More than 20 different species of trees can be used to make syrup. Here on the farm, David is experimenting with basswood, poplar, hickory, sycamore and the beech he’s been showing me. Right now most alternative syrups are a lot more expensive than maple, largely because that sap to syrup ratio is so much higher. Still, David says there is a niche market for his syrups.

MOORE: I would sell to farmers markets in the beginning and specialty food stores. Several different restaurants, and also a lot of mail orders.

Harvesting sap from a birch tree. Maple trees are not the only sources to make syrup. (Photo: Ole Husby, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

BASCOMB: I’ve never had anything other than maple syrup so to see what I’ve been missing out on he invites me try a couple.

[CLINKING OF SILVERWARE, PLATES]

MOORE: Alright, so I have some birch syrup that I made. And some beech syrup from upstate New York from my friend Mike. So, should we try the birch first?

BASCOMB: Yeah, sounds great.

[BOTTLE OPENING SOUND]

MOORE: There you go.

BASCOMB: Thank you. It looks really really dark, much darker and thicker than maple syrup usually is. Yeah, let me try it. Let me take off the mask here. Wow. It's different. Yeah, it's sweet. It's definitely sweet, but also not at the same time somehow. It's got like a familiar flavor that I can't quite put my finger on.

MOORE: Miso?

BASCOMB: Miso! I don't know about that. Maybe molasses.

MOORE: It's nice as a glaze on red meat and salmon. Yeah. And it's also nice if you mix it with olive oil and balsamic vinaigrette to make a salad dressing. Should we try some beech?

BASCOMB: Yeah, sounds great.

[FAINT SOUND OF TASTING]

BASCOMB: That tastes a lot more like maple syrup.

MOORE: Yeah.

BASCOMB: Yeah, it's really good. I wouldn't I wouldn't think this isn't maple syrup. If you put this on a pancake and gave it to me.

MOORE: I think if we had walnut syrup, here, you would have the same reaction tastes a lot like maple with a little more maybe nuttiness to it. But yeah, birch is pretty different Sycamore I would say is pretty different. So, yeah, cool. I'm glad you like them.

BASCOMB: Yeah, I really do. And I have to say, I really learned something new today. I had no idea before, you know, coming out here to meet you that you could make syrup out of anything but maple. So you really opened my eyes today.

MOORE: Yeah, thanks, Bobby. Thanks for coming out. This was a lot of fun.

BASCOMB: Yeah, it was Thank you.

Even before David Moore finishes his PhD at the University of New Hampshire he may find his research is in high demand. With the changing climate maple syrup production can be a lot more variable. Making alternatives more attractive. I hear sycamore actually tastes like butterscotch or honey but there wasn’t any ready today for me to try on David’s farm. Maybe next time.

By the way, we’re still in the heart of syrup season here in New England but last summer’s heavy rains has producers optimistic that it will be a good year.

Related links:

- Click here for more on how maple syrup is made

- Read more about making syrup from birch and hickory trees

[MUSIC: Gary Burton, “Clarity” on Next Generation, by Julian Lage, Concord Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Chloe Chen, Iris Chen, Josh Croom, Gabriella Diplan, Jenni Doering, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Louis Mallison, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Teresa Shi, and Jolanda Omari.

BASCOMB: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth