May 13, 2022

Air Date: May 13, 2022

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Drought Threatens Hydropower

/ Luke RunyonView the page for this story

Amid extreme drought and record low water levels in the Colorado Basin, the federal government has decided to retain more water in Lake Powell and release less to Lake Mead and beyond. The action preserves hydropower generation for the short term, but as reporter Luke Runyon explains to Host Steve Curwood, the Colorado River basin still faces a long-term water shortage that imperils the future of cities and farms in the Southwest. (11:22)

BirdNote: The Zone-tailed Hawk

/ Michael SteinView the page for this story

Turkey vultures soar over the landscape, searching for dead animals. But the Zone-Tailed Hawk, an American raptor that’s a vulture look-alike, soars with them, its sharp eyes searching for mice and birds that ignore the carrion-seeking birds. Michael Stein has today’s BirdNote. (01:58)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

On this week's trip beyond the headlines Environmental Health News' Weekend Editor Peter Dykstra and Bobby Bascomb consider a record-setting heat wave in India and Pakistan, a positive trend in solar and wind power in the United States and the fate of the law behind the historic Scopes Monkey Trial which prohibited teaching evolution in Tennessee public schools. (05:05)

“SmartICE” Helps Inuit People Adapt

View the page for this story

For thousands of years the Inuit people of Northern Canada have relied on stable sea ice for travel and hunting, but as the climate warms the ice is growing dangerously thin. Now, some Inuit communities are working with SmartICE, an organization that uses sensor and GPS technology along with Inuit traditional knowledge to help find safe passages over sea ice in real time. Rex Holwell is Inuit and the North Production Lead for SmartICE and he joined Host Bobby Bascomb to discuss how this technology is helping communities on the frontlines of climate change. (09:58)

Invasive Jumping Worms

/ Kara HollsoppleView the page for this story

Jumping worms, native to Korea and Japan, are spreading quickly across several states within the U.S. The invasive worms degrade soil texture as they eat and deplete it of nutrients, causing problems for gardens and lawns. This week, Kara Holsopple of the Allegheny Front reports on how to spot and avoid jumping worms and what to do if you encounter them. (04:40)

How to Save the Climate

View the page for this story

The Earth is hurtling toward climate disaster as evidenced by many scientific studies, including the latest results from the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Yet the world continues to rely heavily on fossil fuels and drag its heels on transitioning to clean energy. Harvard University Professor of the History of Science Naomi Oreskes joins Host Steve Curwood to note climate change science is unequivocal and why the paths to solving the climate crisis are political and social. (13:55)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

220513 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Rex Holwell, Naomi Oreskes, Luke Runyon

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Kara Holsopple, Michael Stein

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

I’m Steve Curwood

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb

The federal government has taken unprecedented steps to restrict the flow of the Colorado River.

RUNYON: These are emergency measures that the federal government is taking in order to preserve hydro power. And Lake Powell over the next year still has a possibility of losing hydropower production so even with these measure I don’t think we’re out of the woods.

CURWOOD: Also, the social and political costs of fossil fuels beyond climate disruption.

ORESKES: The war should be a reminder to us of how many good reasons there are to act on the climate besides just the climate system itself. If we had started the process of transitioning away from fossil fuels to renewable energy, if we had started that back in 1988 when the IPCC was first gathered we could have made that transition by now.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Drought Threatens Hydropower

Glen Canyon Dam forms Lake Powell, one of the largest man-made reservoirs in the United States. (Photo: Udo S, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston this is Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Western water is in trouble, thanks to the rising temperatures of climate change and a record-breaking drought that’s been decades in the making. The extensive water project built nearly a century ago in the Colorado River Basin delivers both water and hydroelectric power to millions of people in the Southwest. And now to keep electric power generation from being cut off the federal government is taking the unprecedented step of holding more water in Lake Powell, behind the Glen Canyon Dam, instead of releasing it to Lake Mead and beyond. Both reservoirs are sitting with record low water levels. For more I’m joined now by Reporter Luke Runyon who covers the Colorado River. Welcome to Living on Earth.

RUNYON: Hey, thanks. Good to be here.

CURWOOD: So how far is it to say this is the first time the federal government is stepped in a big way to say that there are some restrictions now on the flow of the Colorado?

RUNYON: Well, it's not completely unprecedented. The federal government has kind of always played some role in management of the Colorado River. But I think the latest announcements from the federal government are impressive in their scope, and in sort of the precedents that they're setting. And so the decisions that have come out recently, and the proposals from the Biden administration are twofold. One is to restrict the amount of water that would be released from Lake Powell, which is the nation's second largest reservoir on the Colorado River. And the second would be to release a really large volume of water from reservoirs upstream of Lake Powell in order to preserve its hydropower production capacity. And, and really, these are kind of emergency measures that the federal government is taking in order to preserve that hydropower. That's really the sole thing that the federal government is interested in protecting right now. And Lake Powell over the next year still has a possibility of losing hydropower production. So even with these measures, I don't think we're out of the woods when it comes to that.

CURWOOD: Luke remind us of the scale of the Colorado River watershed. Where does the water come from? And how many states in the US and Mexico does it flow across and serve?

RUNYON: Yeah, the Colorado River is a really critical water supply for almost the entire American Southwest. And in the US, its watershed crosses seven states, and that watershed is split into two basins. So you have the upper basin states of Colorado, Wyoming, Utah and New Mexico. And then the lower basin states are Nevada, California and Arizona, the river also crosses over the US Mexico border, and two Mexican states use water from the Colorado River, you also have 30 federally recognized tribes in the basin. So there's a lot of entities, agencies, cities, agriculture, that rely on this water supply. And it's really critical because this area of the country is incredibly dry. And it's a very arid region of the country. And the Colorado River is really the only substantial water supply for for this region.

Lake Powell is holding around 25% of its total capacity in the spring of 2022. (Photo: Zetong Li on Unsplash)

CURWOOD: So let's talk about the major reservoirs, Lake Mead and Lake Powell, as you say, they're kind of running low, just how low are they currently and in comparison to last year?

RUNYON: So the two largest reservoirs in the country are on the Colorado River. And those are Lake Mead outside of Las Vegas, and Lake Powell on the Arizona Utah border. And Lake Powell is currently at 24% of its capacity. Lake Mead is at 30% of its capacity. And both of those reservoirs that's a record low for both of them. And just the other day, Lake Mead dropped low enough that one of the intakes that the city of Las Vegas uses to draw water from Lake Mead was exposed and was sitting above the lake level. And so I think once people start seeing images like that, the concern level and the alarm bells start ringing a little bit harder and louder. And residents of the Southwest, I think are maybe paying more attention to what's going on at those large reservoirs now that we're seeing some of these impacts.

CURWOOD: And so the federal plan talks about an increase there for Lake Powell with I guess, water from the upstream dam, what's going on here and how does this decision affect the hydropower supply stability situation?

RUNYON: Well, as the reservoir declines, it loses the capacity to produce hydropower. And part of it is based on the water pressure. So if you have a really full reservoir, that rush of water through the dam can generate a lot of hydropower. So the capacity for power generation is already diminished. What the concern is now is a total loss of hydropower production at Glen Canyon Dam. And that's something that the federal government with the Bureau of Reclamation was seeing in its models that if actions weren't taken, the reservoir was going to be rapidly approaching a level to where hydropower production would not be possible. It would hit a level where you couldn't send water through those hydropower intake.

CURWOOD: And of course, Lake Mead gets almost all of its water from releases from Powell. So the decision to hold back water at the Glen Canyon Dam will cause it to fall even lower. I mean, what does that do to the water supply? In places like Arizona and Las Vegas?

Arizona farmers typically rely on water from the Colorado River to irrigate crops. (Photo: Yooperann, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

RUNYON: They're having to have harder discussions about how to rein in their water use. And this is really kind of the crux of the whole problem on the Colorado River right now is, it's always been a story of supply and demand. And what we're seeing is that the supplies keep shrinking. And the demand has not shrank alongside those shrinking supplies. And now it's getting to a point where the reality on the ground shows that if we don't shrink our demands on the Colorado River, we're going to drain these giant reservoirs. And so in states like Arizona, in particular, in Arizona, they're having to have hard discussions about who takes less water from the Colorado River. Under what condition do they take less water? Who has to use less? And when and the the hardest cutbacks really are falling on something called the Central Arizona Project. This is a large, more than 300 mile canal that sneaks its way through the deserts of Arizona to deliver water to Phoenix and Tucson, and to agriculture and tribes in central Arizona.

CURWOOD: Oh, man. I mean, so let's say you're in the agriculture business, you're growing something? How do you get by with less water? Or if you're resident and you want a glass of water? How do you get by with less water?

RUNYON: Those are the hard discussions that are taking place in the Colorado River Basin right now. And in particular, in parts of the lower basin that are going to be taking these really large cutbacks. So say, you're a farmer in central Arizona who relies on this water from the Colorado River that's being cut back, you might switch to groundwater, and start pumping water out of the ground in order to irrigate your crops, you might be investing in irrigation technology that makes your operation more efficient. You might be switching crops, you might be retiring all together and saying I'm not going to stay in agriculture when my water supply is being restricted in this way. And I think you're probably seeing all of those play out in Arizona, right now. You know, when it comes to cities, their focus really is on outdoor water use. And you're starting to see a lot more cities focusing on lawn removal, lawn buyback programs, investing more in that, because in homes and you know, a lot of water can be recycled and reused and put back in rivers. It's not a loss to the system. But when you're watering a lawn, that is a loss, that is water that's not being returned to a stream. And so I think cities are seeing that as a potential bank of water that they can use. It's like start mandating people to take out their lawns. And you're seeing that in cities like Las Vegas,

CURWOOD: Now how has these limits on water affecting the different tribal nations that that rely on the Colorado?

RUNYON: Kind of runs contrary to the overall message in the Colorado River Basin, which is everyone needs to use less water in order for us to survive and to kind of keep the whole region healthy. But on tribal lands, there's a lot of water rights that were never fully realized that are senior, so highly protected old water rights, that tribes were never given the opportunity to use. And I think you're increasingly hearing a call for there to be more use of water on tribal land within the Colorado River Basin. And that seems to be the kind of just thing to do. But it runs slightly contrary to this overall message of we all need to use less water, when really in some pockets, there probably needs to be more water use because the tribes had been denied that in the past.

CURWOOD: What about migration for the ag industry? There are a couple of folks who have suggested that the lower Mississippi River has plenty of water, plenty of bottom land, and even not terribly expensive labor. And these days, they don't have much of a water shortage problem, to put it mildly. If anything, sometimes they get flooded out.

Reporter Luke Runyon covers the Colorado River basin for KUNC and 20+ NPR stations in the southwest. (Photo: Courtesy of Luke Runyon)

RUNYON: Yeah, I mean, it's difficult because in parts of the Colorado River Basin, you can essentially have a year round growing season. So in Yuma Arizona, in the Imperial Valley of California, in those desert climates, you could be growing food almost 12 months out of the year, which is not what you can do in you know other parts of the country where you're restricted by long, cold winters. And the limiting factor is water availability. And so if you know farmers are able to keep irrigating, I mean these areas of the country are intensely farm. So if you're eating a salad in December in New York City, there's a really good chance that lettuce was irrigated with Colorado River water. And so I think sometimes it can be really easy for people in different regions of the country to feel like, oh, this is that region's problem and we don't really have to worry about it. No, our diets would have to change if the Colorado River was not irrigating romaine lettuce in parts of the Desert Southwest. So we're all connected.

CURWOOD: Luke Runyon is a radio reporter who just completed a year of study on a fellowship at the University of Colorado. Luke, thanks so much for taking the time with us and I look forward to hearing you back on the air soon.

RUNYON: Thanks, Steve.

Related links:

- Los Angeles Times | "As Colorado River crisis deepens, government will release less water from Lake Powell"

- New Yorker | "The Lost Canyon Under Lake Powell"

- Previous Living on Earth discussion with reporter Luke Runyon about the Colorado River basin

[MUSIC: Enya, “Miss Clare Remembers” on Watermark, by Enya, Reprise Records]

BASCOMB: Coming up – Inuit communities in Canada’s far north are building resilience in the face of dramatic climate change. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org. Support also comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Dan Kaplan, “Shuffle & Skip” on Vera Hall, by Dan Kaplan, VH001 available on CD Baby]

BirdNote: The Zone-tailed Hawk

The Zone-tailed Hawk (right) and Turkey Vulture (Photo: Eric Bruhnke)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

CURWOOD: A common sight in the skies of the American South West is the Zone-tailed Hawk, which has an unusual way to sneak up on its prey. BirdNote’s Michael Stein has more.

BirdNote®

Zone-tailed Hawk: A Vulture Mimic?

[Zone-tailed Hawk cry, http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/140253, 0.15-.18]

The Zone-tailed Hawk of the American Southwest looks a lot like a Turkey Vulture. It’s dark all over, has a long tail, and soars on long, upward angled wings while tilting from side to side. And – this is where it gets intriguing – Zone-tailed Hawks often soar among groups of Turkey Vultures.

But there’s a crucial distinction between the two, especially if you happen to be a dove or lizard exposed on the terrain below. While the vultures are searching for carrion, the Zone-tailed Hawk in their midst is hunting live prey.

[Zone-tailed Hawk cry, http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/140253, 0.15-.18]

By consorting with vultures, a Zone-tailed Hawk gains a distinct advantage as a predator. Because while doves and lizards would quickly flee the flight silhouette of a Red-tailed Hawk, they seem to ignore the shadow of a vulture overhead, a bird that poses no threat. So floating among the vultures, a Zone-tailed Hawk is a sort of wolf in sheep’s clothing – and can sneak up on its prey undetected.

Just how Zone-tailed Hawks developed this relationship with Turkey Vultures isn’t clear. But we do know that Zone-tails occur only within the geographic range of vultures. And they don’t just soar with them – they also nest and roost near their scavenging accomplices.

[Zone-tailed Hawk cry, http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/140253, 0.15-.18]

###

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. 140253 Recorded by Gerrit Vyn.

BirdNote’s theme music was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Sallie Bodie

© 2016 Tune In to Nature.org September 2016 Narrator: Michael Stein

http://birdnote.org/show/zone-tailed-hawks-mimic-vultures

CURWOOD: For photos soar on over to the Living on Earth website, LOE dot org

Related links:

- Listen to the original story on the BirdNote® website

- More on Zone-tailed Hawks from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology

[MUSIC: Shakey Graves, “If Not For You (Demo)” Shakey Graves And The Horse He Rode In On (Nobody’s Fool and The Donor Blues EP), Dualtone Music Group]

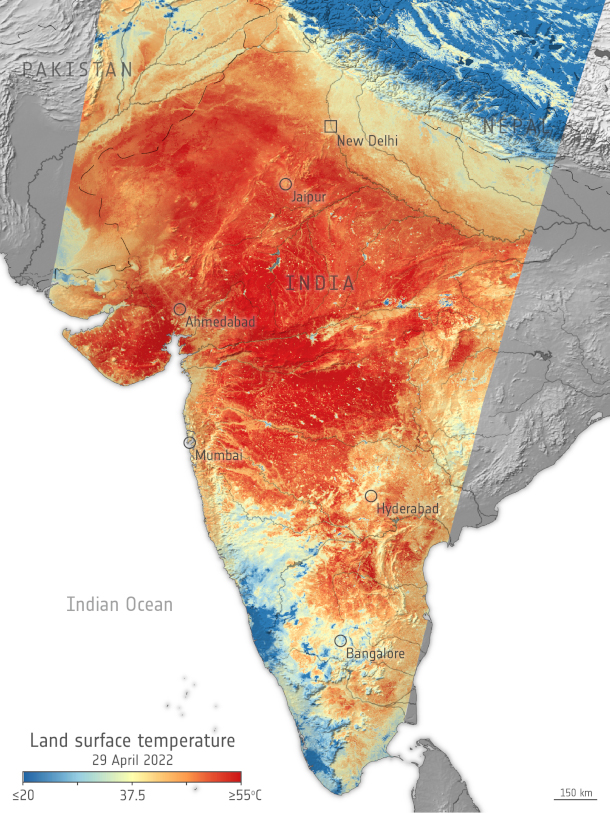

Beyond the Headlines

The heat wave in India and Pakistan has been ongoing since March 2022. (Photo: Copernicus Sentinel data, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA IGO 3.0)

BASCOMB: Well, it's time for a trip beyond the headlines this week with Peter Dykstra. Peter is an editor with Environmental Health News. That's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. Hey there, Peter, what do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Bobby. You know, there's been an absolutely unprecedented scorching heatwave in the middle of the spring in India and Pakistan, temperatures up to 120 degrees Fahrenheit. In one Indian state alone, the early numbers say 25 people have died, the full number's likely to be much, much more than that. 122 years worth of record keeping on weather in India, this was the hottest month of March they've ever had.

BASCOMB: My goodness, 25 people have died in one state, you said, I'm sure that number's got to be much higher.

DYKSTRA: That's right. And as the heat has gone through April, and now the first half of May, there's a very tragic irony in all of this. India has seen tremendous growth, population estimates are now 1.4 billion. They've also seen tremendous economic growth. And that rise in the standard of living involves buying refrigerators and involves buying air conditioners, all of which adds to the power demand. India's building and expanding its coal plants, so the problem is getting worse rather than better.

BASCOMB: Sure, yeah. It's a terrible feedback loop.

DYKSTRA: It is.

BASCOMB: Well, what else do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Well, here in the US, we have our own problems with oil and gasoline and coal and natural gas. But on the solar front, some really encouraging news, courtesy of PV Magazine. That's an industry publication, Photovoltaic Magazine. But using the Department of Energy's own statistics, they've crunched the numbers, and they say that solar power generation increased by 36%, in just a year, from the first two months of 2021, to the first two months of this year. 36%. If you're a Wall Street analyst, and you're looking at that kind of growth, you have to be looking very seriously at investing in the solar industry, maybe wind power as well.

Solar power generation in January and February of 2022 is 36% higher than in the first two months of 2021. (Photo: Oregon Department of Transportation, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: Did they have anything to say on wind power?

DYKSTRA: Wind power, crunched the numbers a little bit differently. But wind power is now 9.2% of all large utilities' electric generation. That too, is a big jump. We're seeing wind power finally get moving on offshore wind farms, onshore wind farms. Traditionally oil and gas states like Oklahoma, Texas, both are catching on. Both are not going to be slowed down. And both have pardon the pun, the wind at their backs.

BASCOMB: Well, gosh, I hope so. I mean, we've all seen gasoline prices and the price of a barrel of oil go up so dramatically in the last few months. It seems like these alternative energies would be looking pretty attractive right now.

DYKSTRA: Pretty attractive, and they don't bounce up and down at the whim of the world's oil markets, a big factor in what we're seeing now.

BASCOMB: What do you have for us from the history books this week, Peter?

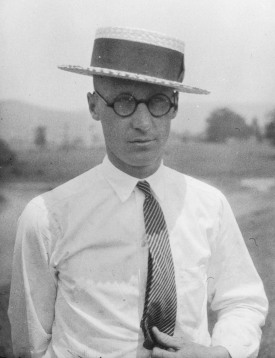

DYKSTRA: Something from May 13, 1967. The final chapter is written on the Scopes Monkey Trial. That was something that happened in Dayton, Tennessee, in 1925. Tennessee had a state law called the Butler Act, which outlawed the teaching of evolution in Tennessee schools. A substitute teacher named John Scopes, was arrested and put on trial for doing exactly that, teaching evolution in a Tennessee public school. He was found guilty. The law stood for another 42 years, before the Tennessee legislature finally repealed it on May 13, 1967. It took that long for the Tennessee legislature to acknowledge solid science, it kind of makes you wonder about other things.

High school teacher John T. Scopes was accused and put on trial for violating Tennessee’s Butler Act, which banned the teaching of human evolution in public schools. (Photo: Watson Davis, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

BASCOMB: Yeah, it does. I mean, 42 years to acknowledge the science of evolution, how long will it take us to acknowledge the science of climate change?

DYKSTRA: Climate change, or sexuality, or vaccines, or all the other things that are being forced back in the headlines now. We're sort of turning the calendar backwards on ourselves. Let's hope some of these things can work themselves out quicker than the 42 years it took for Tennessee to stop making a monkey out of itself.

BASCOMB: Yeah, for sure. Let's hope we can learn from the mistakes of the past, huh?

DYKSTRA: Right.

BASCOMB: All right, well, thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News. That's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, Bobby, thanks a lot, we'll talk to you soon.

BASCOMB: And there's more on the stories on the Living on Earth website, that's LOE.org.

Related links:

- Inside Climate News | “An Unprecedented Heat Wave in India and Pakistan Is Putting the Lives of More Than a Billion People at Risk”

- PV Magazine | “Solar Generation Up 36% in the First Two Months of 2022”

- More on the Scopes Monkey Trial

[MUSIC: The Osborne Brothers, “Rocky Top” (State Anthem of Tennessee), by Boudleaux and Felice Bryant]

“SmartICE” Helps Inuit People Adapt

The Arctic is warming at a faster rate than the rest of the world. Scientists at the California Institute of Technology and the University of Washington observed that Arctic sea ice thinned 1.5 feet (0.5 meters) between 2018 and 2021. (Photo: Kathryn Hansen, NASA, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: The Arctic is warming faster than nearly anywhere else on earth, scientists estimate it is warming at roughly twice the rate of lower latitudes. That means the sea ice is increasingly unstable and unpredictable, which makes life in the Arctic difficult for many Inuit people who rely on stable sea ice for travel. Rather than give up and stay home, Inuit communities in Canada’s far north have mobilized for resilience. They developed SmartICE, an innovative technology that uses both stationary buoys and sensors that trail behind a snow mobile to gather data on ice conditions. That data in conjunction with GPS technology can give Inuit travelers information about the ice that can make the difference between life and death. For details I’m joined now by Rex Holwell, he is Inuit and Manager of Nunatsiavut Operations. He joins me now from Nain, the northernmost permanent settlement in the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador where he says the sea ice is crucial for their subsistence.

HOLWELL: A lot of people here rely on seal for the food. A lot of people rely on Arctic char for fishing. And you know, traditionally, like Inuit have always relied on sea creatures to feed them and it's still the case to this day. The sea ice is our highway. If you can imagine if you living in your little community, if you're only able to travel on your main street to the first stop sign, you're pretty limited on where you can travel. For us it's the same way, when we don't have sea ice. You know, when the sea ice finally comes in, it opens up our highway. So when the sea ice freezes inn, and it's nice and safe to travel on, it allows everybody to travel to go to their hunting grounds to go get the seal, to go get the caribou. It gives you the freedom to go to areas that may not be hunted or over harvested. So the sea ice is vital to our culture, not just for hunting, but I mean to be able to go out and to get seals and caribou and to harvest their furs and their skins to make traditional clothing such as seal skin boots and seal skin mitts. It's vital to the Inuit people.

BASCOMB: Now I don't need to tell you that the Arctic is really on the frontlines of climate change. It's warming faster than any other region on Earth by many measures. Can you tell us please about the changes that you've seen on the landscape just in your lifetime?

HOLWELL: One story that I always tell is when I was a young boy in Nain the sea ice would sometimes be freezing in the harbor, sometimes as early as early December. And you know, they would come in and freeze and stayed through the whole year. But now 2021 last year, so last year, it didn't freeze nice and solid and safe enough that people weren't actually traveling on the sea ice till it was almost the end of January. So you know, in my lifespan and from when I was young boy to now, 40 years, I'm seeing that the sea ice is taking a month and a half later to form safely. So we're getting we're seeing it firsthand here. And you know, when the sea ice isn't as thick, a lot of the people can't predict how the sea ice is as reliably as they used to back, you know, 40 years ago, when we had warmer temperatures and a thicker ice. So people who have their traditional knowledge, they're unsure if their traditional knowledge will keep them safe because with climate change, it's making the sea ice so unpredictable, that again, those traditional ways may not be the right way anymore.

BASCOMB: And so if those traditional ways aren't working and the sea ice is coming later, and perhaps even thinning out earlier in the season earlier, you know, towards summer, how does that affect people? I mean, you said that it makes it more difficult to get to their hunting grounds and to travel. But what does that actually mean in a person's day to day life?

Andrew Arreak is Inuit and the Regional Operations Lead for SmartICE in the Qikiqtaaluk Region known as Pond Inlet. (Photo: Courtesy of Rex Holwell)

HOLWELL: So for a lot of people here, you know, in Canada's North, the cost of living is huge. So you know, a good size seal will feed a family for two or three days. But if the sea ice isn't safe enough and that person isn't going out hunting for the seal, you know, they'll have to rely on a store. So just for the cost of say, a tank of gas in your snowmobile and to feed the same family for the two or three meals that one seal would have cost him for the cost of a tank of gas, you know, that's going to cost them three to four times as much to buy the stuff in the store as opposed to being able to go out and harvest that seal to feed their family. Some of the older Inuit people say, you know, I don't feel full when I eat chicken or beef, because I mean, they've grown up eating seal their whole life and it's more nutritionally dense, it has more nutrients, and it's protein rich. So there is some truth to that. You can buy processed foods in the store that are not as healthy as seal meat or caribou meats. So, we're finding with people getting away from their traditional diets to leading them into more health issues in the future.

BASCOMB: Now, I understand that you are working on a really innovative solution to this problem of the ice thinning and coming later in the season and just being so unpredictable. Can you tell us please about SmartICE and the goals that you have with this project?

HOLWELL: So SmartICE was actually founded because of climate change. Back in 2009, here in Nain Labrador where I am, we had rain in January, in 2009 and 2010. In January, in January, in this area, it's supposed to be minus 40.

BASCOMB: Wow.

Rex Holwell is Inuit and the SmartICE Regional Operation Lead for Nunatsiavut. (Photo: Courtesy of Rex Holwell)

HOLWELL: So climate change led to the founding of SmartICE. So what we do here in SmartICE is we are a not for profit social enterprise. And one of the main things that we do is we manufacture a stationary ice measuring sensor that's actually made here in Nain, Labrador. And if you can just really imagine a nine foot long thermometer that measures ice thickness, and this is what the SmartBUOY does. And we have a separate ice measuring center called the SmartQAMUTIK. If you can imagine somebody's towing behind a center on a sled behind a snowmobile and as that person is operating the sensor as they're traveling along, it'll tell them in real time how thick the ice is. So they can travel on the sea ice for you know, as little as 20 minutes or they can go, I just recently went for a ride yesterday that took me eight hours long. And as I'm traveling along on the sea ice, you know it's measuring the sea ice thickness as I'm traveling along. Then when I get back to my home base, it will automatically upload the data into a website where everybody who wants to access this data is free for them to do so. And we try to get the data out to as many people as possible in the community, you know, we'll post it on Facebook, we'll print off images, and we'll put them up into stores and in the post office. You know, a lot of people here in Canada's North don't have phones or internet. So we want to get the data to as many people as possible.

BASCOMB: So just to be clear, if you are out and you have one of these sensors on your snowmobile, you can see in real time, okay, I'm maybe getting to a point that's unsafe, I should turn around. If you don't have one of these sensors, and say you're planning a trip the next day to go out to your hunting grounds or something, you can just go to the local post office and look at a map and say, oh, gosh, I maybe I shouldn't do this right now or plan a different route. Is that basically true?

HOLWELL: Yes, it's just like a GPS. It's just like, you know, people using your phone, it's a tool that they can use to help make informed decisions when you're traveling on the sea ice.

SmartICE members deploying SmartBUOY, a stationary sensor which measures ice thickness and snow using thermistors. (Photo: Hamlin Lampe)

BASCOMB: Tell me more about how would people traditionally assess the ice to make sure it's safe? I mean, I've gone ice skating where you have to get out an axe and you measure how thick is the ice is, but you can't be doing that if you're traveling, you know, hundreds of miles potentially across the ice or maybe not that far. But what are the traditional ways of making sure that the ice is safe?

HOLWELL: So traditional ways? You know, it actually doesn't very much with what you were saying, if you were traveling with your axe. You know, traditionally if Inuit people were traveling on the sea ice they would carry harpoon with them. And we always tell people, you know, if you're traveling long, and you're unsure of the ice, get off your snowmobile, and you take your harpoon. And if you really stabbed the ice really hard, one strike, if it goes through is not safe to walk on. If you have to strike the ice twice, and it doesn't go through, then it's safe for you to walk on. And if you strike the ice three times with the Harpoon, then it's safe for you in the snowmobile. So that's traditionally how they would check the ice. But you know Inuit people were more of an oral history, teaching people. So you know, a lot of the people who went out seal hunting on the sea ice, they learned from their grandfathers, from their fathers, from their uncles. It was just traditional oral history that it was passed on from generation to generation on how to keep safe while they were traveling on the sea ice.

The SmartQAMUTIK, pictured above, is towed behind a snowmobile and provides real-time ice and snow thickness measurements along community trails. SmartQAMUTIK trips are completed at least once per week and data is made available to the community on SIKU.org. (Photo: Lynn Moorman)

BASCOMB: Rex, a lot of what we know about the Arctic ice is from the perspective of oil and gas companies that want to know about shipping routes or scientists that are worried about permafrost and the emissions that can come with it. But SmartICE is really a body of information by and for Native people in the Arctic. These are people who are trying to live their normal lives, while the world is quite literally changing around them right in front of them. What does it mean to you and your community to have this kind of information made by you and for you?

HOLWELL: That's a great question. You know, who better to have handle these technologies and the new learnings and to interpret the data that comes from other agencies, then somebody from your community. So that's one thing that we really believe in, you know, with SmartICE operators, you know, we want the locals to do their routes, because they know where the majority of the people go. So they want to do the routes that will help keep their people safe. One project that we're doing is we're actually using satellite imagery. And we're trying to interpret it into usable maps for the people from the community. Like you mentioned, a lot of these maps that you can find online they're not meant for people in their communities to go to do it or traditional hunts, they're for the ships to go into or pass these communities safely. We're actually hiring on local people, teaching them how to read this data and how to take that data and turn it into something useful that their community can use to help keep them safe while they're traveling on the sea ice.

BASCOMB: Rex Holwell is manager of Manager of Nunatsiavut Operations. Rex, thank you so much for your time today.

HOLWELL: Oh, you're welcome. I was glad to be here and to help spread the story of the Inuit people and what we do with SmartICE.

Related links:

- Learn more about SmartICE

- Bloomberg | “How the Inuit are Reshaping Arctic Climate Science”

- Kicker | “SmartICE and Choices for Youth Make Waves in Northern Communities”

- Atlantic Business | “Climate Change: Ground Zero”

- Exploring by the Seat of Your Pants | “The SmartICE Story | Blending Indigenous Knowledge with Advanced Science”

[MUSIC: Juurini, “Saimaniq” Single, Joey Partridje]

CURWOOD: Coming up – Harvard historian Naomi Oreskes on how to save the climate. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Marilyn Morales/Kirk Whipple/The Unconservatory Festival Orchestra, “Sevillana Linda” on Danzas Para Does Pianos y Orquesta, by Marilyn Morales, self-published]

Invasive Jumping Worms

Jumping worms can grow up to eight inches long. When disturbed, they move like a snake, sometimes appearing to be jumping as their namesake would suggest. (Photo: Njh5880, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb

As people take care of lawns and gardens this spring they may encounter a new and unwelcome kind of worm. Jumping worms native to Japan and Korea are larger than earthworms and wriggle more like a snake. These invasive worms have been found across much of the eastern half of the United States and can be extremely damaging to soil quality. Kara Holsopple has been digging into the story for the Allegheny Front and has more.

HOLSOPPLE: It was about seven years ago when Nancy Canals first spotted them in Pittsburgh.

KNAUSS: I was working in my own yard, just digging up the ground and I thought- what are these things they don't look like your earthworms.

HOLSOPPLE: Canals is the Statewide Master Gardener Coordinator for Penn State Extension, so she knows her worms. These were large and they behaved more like snakes than common European earthworms.

KNAUSS: They ride around and jump and I'm thinking there's so many of them, these are different!

HOLSOPPLE: With a little research, she solved the mystery. They were Asian jumping worms and in a garden or forest habitat, they're a real problem canal says.

KNAUSS: The jumping worms actually degrade the soil. Your soil texture will change. So it's very granular, and people often compare it to coffee grounds.

HOLSOPPLE: She says the invasive species which lives close to the surface can eat anywhere from two to three times its body weight in soil every day. Those coffee grounds are the castings the worms excrete.

KNAUSS: What happens is if you get a rainstorm, the rain will hit those castings and you'll get a large flush of nutrients that will be available and the plants really can't absorb them all. So very little of those nutrients may reach some of the plants.

HOLSOPPLE: The nutrients just wash away and that can leave the soil depleted. Canal says researchers are looking at how the phenomenon could impact the germination of maple seedlings which rely on that upper layer of soil. In gardens, it presents other headaches.

KNAUSS: Personally I had a wild ginger just ground cover wild ginger growing in my garden, and it completely disappeared once I had the Asian jumping worms. So you now have bare soil and then that can leave space for your invasive plants like stoke grass, knotweed, garlic mustard to sort of take over.

HOLSOPPLE: Though not all plants are susceptible Knauss says the jumping worms can even live below turf grass, damaging the lawn so that it just lifts off. She says now is the time to prevent them in your yard. Because while the adults are annual and die off in the winter, their cocoons do not.

KNAUSS: These cocoons are very small, they're the size of a mustard seed. So while you are sharing plants with neighbors and you don't see any worms, there could be many, many cocoons in that soil.

HOLSOPPLE: In April when temperatures reached 50 degrees consistently. The cocoons hatch Knauss says if you're going to plant sales or trading with neighbors, the plants should be washed to remove garden soil.

KNAUSS: They can either be sold bare root, or they could be potted up in a sterile medium and then shared with somebody.

HOLSOPPLE: She says the cocoons are in mulch too. So buy it from a reputable dealer and make sure it's been heated to 130 degrees Fahrenheit. If prevention measures have failed, and you do end up having some of these in your yard or your garden, what can you do about them?

KNAUSS: One way that you can get rid of the cocoons is by solarization. So this is something that you do in late spring or early summer when our temperatures are high. You want to wet the area where you know you have the jumping worms and then cover it with clear polyethylene not black plastic, and let that heat up for two to three weeks until the soil temperature exceeds 104 degrees Fahrenheit for at least three days.

HOLSOPPLE: To get rid of the adults, you have to use your hands.

KNAUSS: I've done plenty of hand picking myself. You want to just put them in a plastic bag and set the bag in the sun and then throw it in the trash. You can also use a dry mustard solution. So making a solution of 1/3 cup of dry mustard in one gallon of water, and then you drench the area. And this mustard irritates the worms. It brings them to the surface so then you can easily harvest and pick them and throw them away.

HOLSOPPLE: What did you think when you saw the Asian worms in your garden?

KNAUSS: Actually, I was a little creeped out because I you know I'm not a fan of snakes. And then you know I learned more about it and unfortunately they're with me now.

HOLSOPPLE: You still have them?

KNAUSS: Yes, I do.

HOLSOPPLE: So the bottom line is if you can help it. Don't let Asian jumping worms happen to you or your garden.

BASCOMB: That story from reporter Kara Holsopple comes to us courtesy of the Allegheny Front.

Related links:

- Find this story and more on the Allegheny Front website

- Information from the Department of Natural Resources about Jumping Worms

- Kara Holsopple’s bio on the Allegheny Front website

[MUSIC: Orchestra Baobab, “Gnawoe” on Mouhamadou Bamba (Remastered Reissue), by Orchestra Baobab, Jambaar Records/Syllart Records]

How to Save the Climate

Youth activists participating in a climate protest in Santa Rosa, California. (Photo: fabola, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: There is now a steady drumbeat of increasing climate peril. Researchers at the UK’s Met Office have just reported there’s a 50-50 chance that sometime in the next four years there will be a year when the average mean global near-surface temperature will exceed 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. A brief blip at that level does not spell immediate disaster, scientists say, but if it becomes a long-term trend we will be in deep trouble, which is why staying below a 1.5 degree increase is the target of the Paris Climate Agreement. The Met Office report comes on the heels of dire warnings last month from the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. The IPCC says we must act before it is too late to avert a horribly overheated climate, yet emissions keep rising, especially from huge amounts of methane linked to the natural gas industry. We face an existential threat of historic proportions, so we thought we’d call up a historian for some guidance. Naomi Oreskes is a Harvard Professor of the History of Science. Naomi, welcome to Living on Earth.

ORESKES: Thanks, Steve. It's a pleasure to be with you.

CURWOOD: So we thought we'd call you up to ask what's going on? What should we do? Why is it that we are marching in such lockstep towards climate disaster at this point?

ORESKES: Well, in terms of what's going on, I'd say this is a classic good news and bad news story. And most unequivocal statement of the scientific evidence that we have seen to date. My colleagues and I have tracked this for a long time. And one of the things we've noticed is that the IPCC has been very conservative, they've been very cautious. They've tended to understate the threat. The reports were more or less correct. But on the low side, on the conservative side of predicting what would actually happen. This is the first time where I think the scientific community has stated very clearly very accurately, you know, calling the climate spade a spade. So that's the good news. The bad news is how bad the news is, live really wasted 30 years, you know, the IPCC was first gathered in 1988. We have lived through now more than, you know, 30 years of inaction, of disinformation of disingenuous promises. And so now we are at a point of crisis, a lot of climate deniers, the fossil fuel industry, even ordinary people accuse scientists of being alarmist. Well, we have seen that they did not exaggerate the threat, they really called it pretty much correctly, but because we have ignored it now, it really is something to be alarmed at. Now, we are truly facing a climate crisis.

CURWOOD: At what point are we going to act? We've seen this last year, there was the climate summit in Scotland. But about the only thing that was agreed upon there was the ability for Wall Street to trade in carbon emissions, in terms of direct action to help less fortunate countries mobilize in terms of actually getting emissions down, not much has happened.

ORESKES: Well, of course, and we are in a very bad place. To me, the message that we need to get across now is that this is no longer a scientific question. At this point, there's really no science to argue, the IPCC should declare victory, they should close working group one, they should say, we did the job we were asked to do, we were asked to tell you what level of carbon pollution represents, quote, dangerous anthropogenic interference in the climate system, we've given you that answer. And now the onus is on you, the world society, political, business leaders to do something about it. And I think that's really the message that should be front and center now. So we need to shift our attention away from the science, but really focus on the political, social, and economic aspects of this problem. The reason we haven't acted is because of powerful political, economic, and social forces standing in the way deliberately trying to block action. And then just also all the inertia, the normal inertia and status quo bias that we face any time we want to make change.

CURWOOD: We saw President come into office making a lot of noise about doing something on climate. And yet with the war in Ukraine, the same president is saying to the fossil fuel industry drill, baby drill.

Pictured here is Senator James Inhofe (R-OK) visiting the US Embassy in Ukraine on October 27-28, 2014. Senator Inhofe is notable for holding up a snowball on the Senate floor as evidence that global warming does not exist due to the existence of snow. (Photo: U.S Embassy Kyiv, Ukraine, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

ORESKES: I know and this is really astonishing, because the war should be a reminder to us of how many good reasons there are to act on climate besides just the climate system itself, if we had started the process of transitioning away from fossil fuels to renewable energy, if we'd started that process back in 88, when the IPCC was first gathered, or in 1990, when they first issued their report, or 1992, when the world's nations signed the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, we could have made that transition by now, all the technologies that we know are available to fix this problem, have been around already for quite a while they've become much cheaper in the last 10 years or so it's kind of a tragedy of historic proportions. I do think historians will be writing about this for years to come.

CURWOOD: And in fact, the president of the United States is looking at midterm elections where the price of gasoline is seen as an indicator of his possible success, the more expensive gasoline is, the lower his odds of keeping control of one or both houses of Congress.

ORESKES: Well, that's right. And this is where I think the messaging of the fossil fuel industry has been far more effective than the messaging of the people who would like to see action on climate. Some of this, I think, is a legacy of effect of having to find this problem as a scientific problem. Scientists are really not the right people to articulate a new political and cultural vision of what it would look like for us to actually be freed from the stranglehold of the fossil fuel industry. But the Democratic Party and scientists and people involved in the climate issue by and large, have not been good at articulating that positive vision of what this looks like how in the long run, we save money by switching to renewables, how in the long run, we save lives, we improve our health, we generate jobs that can't be outsourced. Our political leaders and the people involved in this issue have not done a good job of articulating it. And so the fear mongers can say, oh my god, the price of gas is going up. You know, we have to drill for more oil and gas even though it commits us to a dangerous future and will cost us billions, if not trillions of dollars in damages, which, of course, the American people, the taxpayer, will be picking up the bill for that.

CURWOOD: This year, we have a forecast of 19 named hurricanes and the United States in 3,4,5, serious ones, and only a handful of people driving electric cars who don't care about the price of gasoline going up at the pump.

This is a photo of a burning vehicle in Luhansk Oblast in March 2022 during the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The war in Ukraine has led to inflation in the fossil fuel market. But the war has also become a catalyst for renewable energy to be considered a viable alternative as it carries far less security risks than fossil fuels. (Photo: State Emergency Service of Ukraine, CC BY 4.0)

ORESKES: Right. So I mean, it seems to me, one thing the President should be doing is announcing a massive incentive program to switch us all to electric cars, but a really front and center program, tax credits for anyone buying electric car. So first of all, to give incentives for people to get electric cars, which are now really great. I mean, electric cars are good to drive, the forces of darkness, want to cast this as a story of sacrifice. But this is really not about sacrifice. It's about transition. But the alternative is actually better. Electric cars aren't just more efficient and cleaner, they drive better, they're faster, they accelerate faster. And again, that's not a message that's getting out in the way that it needs to I mean, Elon Musk has tried, but he's got his own issues.

CURWOOD: Interestingly enough, Musk did this as something cool for the elite to do not something for the masses to save money on maintenance and fuel expenses, and to not have these fumes in the air that kill 300,000 of us early every year in this country from burning fossil fuels.

ORESKES: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, according to the World Health Organization, 7 million people die every year from air pollution, most of which is driven by fossil fuel combustion, 7 million people. I mean, so this is essentially a global pandemic of death caused by air pollution, mostly caused by fossil fuels. But getting back to the elite versus the everyday again, this is why I think the Ford F 150 truck and the whole Ford fleet, right, Ford has announced there's going to be an electric Mustang, you know, electric trucks, electric sedans. I mean, this is fantastic, right. So I would like to see the President, do a giant press conference with the CEO of Ford Motors to announce this initiative and to say, this is an initiative for all Americans, and we will all benefit. And I just think that could be a really powerful message. And honestly, I don't, I don't know why that's not happening.

CURWOOD: Really. You don't know why?

ORESKES: Well, okay. I guess I do know why. Yeah.

CURWOOD: Yeah. Can you say a little?

A cloud of air pollution envelopes the city of Mashhad, Iran. Air pollution prematurely kills 7 million people every year according to the World Health Organization. (Photo: رامین صفاری, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

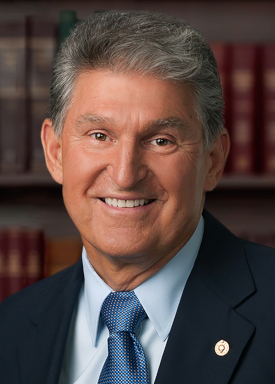

ORESKES: The fossil fuel industry has a stranglehold on Washington, DC. And it's not just the Republicans. I mean, we saw that this year with Joe Manchin's, refusal to play ball. And if you think about it, why are we even in a place where it comes down to one vote, right? There are a lot of people in the Democratic Party who are too close to the fossil fuel industry who are afraid of the fossil fuel industry, the fossil fuel industry does, in fact, target people who stand up against them. But if we don't stand up, then we've given up the fight without a fight. And this is a fight. And it may be dirty, and it may be messy but you know, we have to confront it. Because if we don't, well, then we're looking at 2,3,4 degrees of climate change and massive damage, massive losses.

CURWOOD: Hopefully, the urgency around the use of fossil fuels, because of what's going on in the war in Eastern Europe will abate and people will be able to see that if we weren't so dependent on them that we would have better health and better security. You know, the chief executive of Blackrock, Larry Fink, I don't know, they manage what seven $8 trillion in assets for various people. He said that the war is going to really speed up the greening of, of our economy. But you say that the private side folks may be very helpful. They may be, in fact necessary, but they're not sufficient really to get it done.

ORESKES: Yeah, that is what I think. If we look at history, what we see is that government playing an active role has been essential in all of the major technological transitions of the last century or even more, if we look at the rise of radio or television, or commercial aviation, or rural electrification, what we find is that not one of these was done by the private sector working alone. All of them were done, either by the US government, like rural electrification, or the development of the Internet, or they were done through private public partnership. And so that's why I think that seeing active leadership from the US federal government and state governments, I think that's going to be really important. And I think it's really important for business leaders to reach out to political leaders and vice versa, to figure out what that kind of partnership could look like, in the 21st century.

Senator Joe Manchin, Democratic senator for West Virginia is most notable for his direct support of the fossil fuel industry and for being the Democratic senator who has helped to block President Biden’s climate agenda. (Photo: United States Photography Studio, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: How sufficient Do you think democracy is to this challenge? You and a partner have written a novel a couple of centuries in the future, showing that it was China under a fairly authoritarian regime that best dealt with the climate emergency.

ORESKES: The world's democracies have not been very effective in dealing with this problem. I wouldn't say China has been exactly effective either, but they've taken stronger steps particularly in supporting a powerful solar energy industry. Democracy relies upon the assumption that we have access to good information, and that we can have a free and full exchange of ideas because people are operating in good faith. But if people are lying, and if we're saturated by a sea of disinformation, propaganda, lies, half truths, it makes it incredibly difficult for us as citizens to do our job in a democracy. So I guess another part of this story, a bigger part has to do with disinformation and social media and what steps we need to take to address the spread of disinformation on social media. The myth that many people have the idea that many Americans have that problems are best solved by letting the market do its magic. History refutes it. And so then the question is, why do so many people believe this idea, which is so clearly refuted by experience? And the answer is propaganda. And so we've tracked a 100 year propaganda campaign by American business leaders to promote this free market ideology and to teach us to distrust government. If we don't trust government, then I think we will not actually be able to solve this problem, we really have to address the root causes of people's distrust in government. And some of that, or at least one of the major root causes is propaganda.

Harvard University Professor of the History of Science Naomi Oreskes speaking at the History of Science Society meeting on November 8, 2008. Prof. Oreskes has studied how the distrust of government is linked to corporate propaganda as well as documented the decades long climate denial campaign launched by the fossil fuel industry. (Photo: Ragesoss, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: How do we get from here to there?

ORESKES: Well, that's a great question. And again, if you look at history, I think history tells us that bottom up social movements are really important. And especially if you think about civil rights in America, I like to think a lot about Rosa Parks, partly because she was an ordinary person, but also because Rosa Parks didn't actually work alone. But she was actually part of a social movement that had planned that moment. It wasn't spontaneous. But it's really important for us to understand, social change doesn't actually mostly come from individuals working alone, it comes from individuals working together. And bottom up social movements can be very, very powerful, especially then, if they can be linked with articulate and charismatic leaders like Martin Luther King, there's a role for all of us to play, we all need to get involved. And we shouldn't just be sitting in our seats waiting for the Martin Luther King of climate change to emerge, we should all be getting involved to create that bottom up social movement, and to put pressure on our political leaders, because we know they're getting the pressure from the fossil fuel industry, but they're not getting the same kind of counter pressure from ordinary citizens who care about this issue.

CURWOOD: So Professor Oreskes is what gives you hope in this situation?

ORESKES: What gives me hope is the fact that this thing can be solved. There are the technologies, the innovations, the policies that we need all exist, we know what they are, we don't have to invent some new miracle technology. We don't have to invent some new miracle policy. We have the tools at our disposal. We just have to use them.

CURWOOD: Naomi Oreskes is a professor of the history of science at Harvard University. Thanks for taking the time with us today.

ORESKES: You're welcome. It's been a pleasure.

Related links:

- Mother Jones | “A Closer Look at Joe Manchin’s Ties to the Fossil Fuel Industry”

- The New York Times | “How Joe Manchin Aided Coal, and Earned Millions”

- World Resources Institute | “6 Big Findings from the IPCC 2022 Report on Climate Impacts, Adaption, and Vulnerability”

- Nature | “What the War in Ukraine Means for Energy, Climate, and Food”

- The New York Times | “Naomi Oreskes, a Lightning Rod in a Changing Climate”

- More on Naomi Oreskes

[MUSIC: Enya, “River” on Watermark, by Enya, Reprise Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Chloe Chen, Iris Chen, Josh Croom, Gabriella Diplan, Jenni Doering, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Louis Mallison, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Teresa Shi, and Jolanda Omari.

BASCOMB: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth