March 31, 2023

Air Date: March 31, 2023

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Dire Climate Warning From IPCC

View the page for this story

The world has no more than a year or two to start bending the curve of carbon emissions downward to avoid more drastic impacts of climate change, according to the latest scientific consensus the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. UPenn climate scientist Michael Mann joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss what’s at stake for the planet and what’s necessary to keep warming below 1.5 degrees Celsius. (11:22)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Living on Earth Contributor Peter Dykstra joins Host Bobby Bascomb to talk about Scotch whiskey going green. Also, armadillos are marching north into the Midwest thanks to climate change. And in history, they look back to likely the only time mafia boss Charles “Lucky” Luciano was held accountable for a killing, with the victim a pheasant. (04:26)

Natl Audubon Keeps Enslaver’s Name

View the page for this story

The namesake of the National Audubon Society was an enslaver, racist and white supremacist, so several local chapters are changing their names. But the leadership of the national group has rejected making a change. DC chapter President Tykee James joins Host Steve Curwood to say the decision is an obstacle to a more inclusive birding community. (12:36)

Microplastics – “A Poison Like No Other”

View the page for this story

Microplastics are everywhere scientists have looked for them, from the deepest ocean trenches to mountain peaks. Micro and nano plastics are in our air, water, food, and our own bodies. The recent book “A Poison Like No Other: How Microplastics Corrupted Our Planet and Our Bodies” takes a deep dive into the world of these tiny pollutants laden with thousands of different chemicals. Author Matt Simon joins Host Bobby Bascomb to discuss the dangers and options to address the problem. (17:31)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

230331 Transcript

HOSTS: Bobby Bascomb, Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Tykee James, Michael Mann, Matt Simon

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra,

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

The National Audubon Society is keeping its name despite the association with slavery and racism.

JAMES: John James Audubon enslaved people, he perpetuated indigenous genocide. This is a legacy we're upholding everyday we introduce ourselves to somebody. So we should change it because we can do much better than Audubon ever did.

CURWOOD: Also, scientists are finding microplastics literally everywhere.

SIMON: There was one study that looked at a remote mountaintop in the Alps and detected for nanoplastics, these very, very tiny ones, and found that if you were standing on the top of this mountain, just by standing there for a little while, you would have millions of these nanoplastics falling on your shoulders. That's outdoor air.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Dire Climate Warning From IPCC

The latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Synthesis Report delivered a final warning on the climate crisis, as rising greenhouse gas emissions are now pushing the world closer to warming levels that would collapse civilization. (Photo: Chris LeBoutillier, Unsplash)

BASCOMB: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston this is Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Usually conservative, scientists are now sounding the alarm about climate change. They warn that if the world fails to stop cutting carbon emissions in the next year or so we will burn through the Paris agreement limit of 1.5 degrees Centigrade of average warming, with dire consequences. Since its establishment 35 years ago the collective scientists of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change have been careful to avoid alarmist predictions and have made cautious projections about the advance of global warming. No more. The sixth and latest IPCC synthesis report of its three working groups cautions that the rising incidence of devastating storms, floods, fires, and heat waves show trouble from climate disruption is already baked in, even though we have yet to pass 1.5 degrees centigrade of warming. Getting hotter than that won’t suddenly push us over a cliff but they say unless we immediately start reducing emissions and cut them by 60 percent by 2035, more and more of us will get pulled into a cauldron that will eventually boil away our civilization. Michael Mann was a lead author of the IPCC’s third assessment report and directs the Center for Science, Sustainability & the Media at the University of Pennsylvania. Michael, welcome back to Living on Earth!

MANN: Thanks, Steve, it's great to be with you.

CURWOOD: What are your key takeaways from this latest IPCC report? I think it was 2015 when we last saw a full report, why does this report matter so much?

MANN: This report really is fundamentally different in tone, the IPCC has basically come out and said, Look, we really have a crisis on our hands. Now, we haven't made the progress in lowering carbon emissions that we had hoped to make over the past few years. And so it will take a far more Herculean effort now to keep warming below a catastrophic three degrees Fahrenheit, or one and a half degrees Celsius. This is about as close as you will ever come to hearing the scientific community scream at the top of their lungs from the highest buildings from the tallest buildings. That's basically what we're seeing.

CURWOOD: I think one of the startling lines in the report is that we have to stop increasing carbon emissions right away.

The IPCC report said carbon removals from the atmosphere are key to achieving the Paris Agreement target of limiting the global average temperature rise to below 1.5 Celsius. (Photo: Marcin Jozwiak, Unsplash)

MANN: Yeah, so carbon emissions have sort of flattened, okay, that's the good news here. They're not rising anymore. But the bad news is, it isn't enough to keep them flat, we've got to reduce carbon emissions by 60%. Now, by 2035, if we are to keep warming below three degrees Fahrenheit, where we really will start to see far worse consequences. We're already seeing devastating consequences. But there'll be that much worse if we exceed that level of warming. And to avoid doing that, there can be, for example, no new fossil fuel infrastructure.

CURWOOD: But the world is looking to add more fossil fuel infrastructure. I'm thinking of plans to drill in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, in the peatlands there, the approval of the willow project in Alaska for huge amounts of oil there. To what extent is this report say, no, we have to stop. Right now. We can't do any more infrastructure, we can't increase carbon emissions at all, if we are to have a chance.

MANN: So you're absolutely right, we can't continue these new coal fired power plant projects, new oil and gas pipelines to build new fossil fuel infrastructure. That's a decision to basically lock in place infrastructure that will deliver fossil fuels to the market for decades. That's what we have to stop doing. But ultimately, what will probably be the deciding factor is the demand. And so, if we can put in place the right incentives to shift demand away from fossil fuels, towards renewable energy, then even though that fossil fuel infrastructure is there, it will be less of a return on investment, it will be less profitable.

CURWOOD: So we're in it already exceeding that one and a half degrees Celsius target or three degrees Fahrenheit, roughly speaking, will put us in deeper trouble much deeper trouble. How can we reach this goal now?

MANN: If you look at the provisions of the inflation Reduction Act, independent experts have said that if they are basically implemented on time, that should be enough to keep warming below two degrees Celsius. So that's major progress from where we were headed, say back before the Paris Agreement, where we were headed towards something closer to four degrees Celsius, seven degrees Fahrenheit. Now, if we implement the existing commitments, we're looking at two degrees Celsius less than four degrees Fahrenheit. That's real progress. But it's not enough progress.

The report said increasing temperatures will result in substantially more poverty, extreme heat, sea level rise, habitat and coral reef loss, and drought, and if left unchecked would upend human civilization. (Photo: Rachman Reilli on Unsplash)

CURWOOD: Michael, you said that all things considered, we're probably looking at two and a half degrees centigrade rise closer to four degrees Fahrenheit rise. But there was recently an analysis by the World Resources Institute that says, if we do that, we're going to see fires of the increase in burnt areas across the Mediterranean Europe, for example 60 to 87%, greater than now. These things sound really disastrous. The heat, the extreme heat and fires and kind of the related drought sounds apocalyptic.

MANN: Yeah. And it's sort of interesting. You're absolutely right. And you know, a three degrees Celsius five degree Fahrenheit, warmer world is a world, it's hard to imagine. Because look at the devastating consequences we're seeing now. Just imagine doubling those impacts, making those storms, twice as intense. If we're already struggling to deal with the consequences of climate change fueled extreme weather events. Now, just imagine how much worse it'll be. This is why there's so much emphasis still on trying to limit the warming below one and a half C below three degrees Fahrenheit, because that's a level of warming that we feel we have the adaptive capacity to confront to deal with.

CURWOOD: And by the way, right now we're at 1.1 degrees centigrade warmer 1.2 degrees.

MANN: Yeah, it depends precisely on how you measure it, but we're close. We're at 1.2, I would say C, and we're talking about not going above 1.5. C, that isn't a lot of wiggle room, that's a few tenths of a degree see. And what that tells you is that our budget, our carbon budget, the amount of carbon that we can still burn and keep warming below one and a half Celsius, that is shrinking with each additional year where carbon emissions don't come down sufficiently. And that was one of the key take home messages of this latest IPCC synthesis report.

CURWOOD: Now there is some good news in a way in the IPCC report, because it says that sufficient support could be available for adaptation solutions, build some resilience to these climate risks. I mean, what are some of the most realistic solutions to our dilemma?

MANN: Well, I mean, they're coastal defenses that we can build to, you know, try to insulate ourselves from modest levels of sea level rise, once sea levels get too high, then ultimately, you have to start retreating away from the encroaching seas, and that's very expensive, requires a massive redistribution of infrastructure. So you know, there are things we can do there. When it comes to agriculture, there are ways to use different cultivars to grow different crops to try different strategies of crop rotation. So there are experts in each of these areas that have looked at the possible adaptations that we could take to try to insulate ourselves from sea level rise to try to insulate ourselves from the devastating possible impacts on agriculture, et cetera.

CURWOOD: So to what extent is the bad news already baked in? And what aspects Do we have a better chance to avoid? Do you think?

MANN: Yeah, so you know, the extreme weather events, the heat waves, the wildfires, the floods, the superstorms. To a large extent, those are really related to the warming of Earth's surface, the warming of the ocean surface, the warming of the planet surface. And we know the science tells us that once we bring carbon emissions to zero, the planet's surface stops warming up. So that's really important. So we're sort of stuck with the worsening of those impacts that we've already seen. In the best-case scenario, we've got to live with that. But we can prevent them from getting worse. Now, where things are a little more concerning, is with say, the behavior of the ice sheets, and sea level rise, those sort of components of the system are sort of more cumulative in nature, they are a consequence of sort of the inertia of the climate system and the oceans, you know, will continue to warm up for decades, the surface might start warming up, but the sub surface of the oceans will continue to warm as that heat from the surface sort of diffuses down and penetrates into the deep ocean, and sea level will expand as the ocean continues to heat up. And those ice sheets are very sluggish in their response. So once you start to see the disintegration of those ice shelves, and then parts of the ice sheet, it's very difficult to stop that. And so some of those impacts could continue to get worse. Even if we stop our carbon emissions. Even if we stop the surface of the planet from warming up.

CURWOOD: For the years that you've been working on this. There's been pretty robust discussion about this problem. But at the end of the day, we still aren't headed in the right direction, we may be slowing down, there may be some more awareness. But still, if we continue with the present rate, this report says we're really in for it. We are in the process of destroying our civilization. But what's the bright side here? What's the opportunity here? What's thing that we're missing?

The IPCC predicts the world could warm 2.4 degrees Celsius by mid-century—surpassing critical tolerance thresholds for agriculture and health. (Photo: Karsten Wuerth, Unsplash)

MANN: The reason for cautious optimism here is that we're not heading headlong into the climate crisis in the way that we were, say 10 or 20 years ago with our carbon emissions, they've stopped going up carbon emissions were rising, and that was deeply problematic. Now, they've sort of hit a plateau where they're no longer rising globally. And we know that that is due in substantial part to the decarbonization of the global economy. We are seeing movement away from fossil fuel energy to renewable energy. The obstacles at this point, aren't climate physics, and they're not technology. The obstacles right now are entirely political, and political obstacles can be overcome with enough sort of popular support with an uprising with a global movement like we're seeing now with climate, the Youth Climate movement has really sort of recenter the conversation where it always needed to be on our ethical obligation to act before it's too late. And I do think that we're seeing a tipping point of the good kind, it gives me hope that it's not too late for us to do this.

CURWOOD: Michael Mann is the director of the Center for Science, sustainability, and the Media at the University of Pennsylvania, and author of the forthcoming book, Our Fragile Moment. Professor thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

MANN: Thank you Steve, always a pleasure.

Related links:

- The Guardian | “Scientists Deliver ‘Final Warning’ On Climate Crisis: Act Now or It’s Too Late”

- The Nature Conservatory | “The Latest IPCC Report: What Is It and Why Does It Matter?

- ABC6 | “Most Recent IPCC Report Calls for Urgent Action”

[MUSIC: Darol Anger featuring The Nashville Lumberyard, “John Henry” on Diary of a Fiddler, traditional Amaerican/arr.Anger, Compass Records]

BASCOMB: Coming up – The National Audubon society chooses to keep a name associated with slavery and racism. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Darol Anger featuring The Nashville Lumberyard, “John Henry” on Diary of a Fiddler, traditional Amaerican/arr.Anger, Compass Records]

Beyond the Headlines

A group of 140 Scotch distilleries in Scotland have agreed to achieve net zero carbon emissions to maintain a good reputation among tourists and preserve the local peat bogs. (Photo: PublicDomainPictures, Pixabay)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

Well, it's time for a trip now beyond the headlines. With Living on Earth contributor Peter Dykstra. He's on the line from Atlanta, Georgia. Hey there, Peter, what do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: First, we'll go to Scotland, where there are 140 distilleries that have united to try and make whiskey making net zero. They're using a mix of wind energy, possibly tidal energy, and other things to get away from the traditional use of fuels and peat from peat bogs, traditionally burnt in Scotland for warmth and energy. And they're making some progress, but an awful lot to go.

BASCOMB: Well, that's great. But why the sudden interest in green energy there in Scotland?

DYKSTRA: Well, several things. Number one, in recent decades, the people of Scotland have been very environmentally aware. Number two, whiskey is a huge export in the entire United Kingdom. It's one of the biggest dollar-for-dollar food and beverage exports they have. And number three, a lot of these small Scotch distilleries are tourist attractions, and they want to keep goodwill with tourists. It all amounts to something that is enlightened self-interest for the Scots who makes scotch.

BASCOMB: Wow, well, that's a great example of you know, consumer demand driving progress for the environment. What else do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Little story that's been brewing for 20 years on this side of the pond. And armadillos, you either love them or they're just kind of an ugly little nuisance. They started showing up here in Georgia 20 and 30 years ago, and now there are reports of armadillos as far north as Southern Illinois and Southern Indiana. They're moving north due to climate change as things warm up. Armadillos food source is more available, and they're surviving at much higher rates. There was a study done by researchers at Valdosta State University about 10 years ago that projected that with projections of climate change and warming, that someday we will see armadillos as far north as Washington DC on the East Coast and Omaha in the Midwest.

Due to climate change, Armadillos' habitat is expanding further and further north as the warming winters provide them with food year-round. (Photo: MikeGoad, Pixabay)

BASCOMB: Wow. So what kind of impacts might armadillos have in a new ecosystem? You know, further north?

DYKSTRA: Not much they leave quite a stank when they're dead by the side of the road. They don't tend to be disruptive with other ecosystems. They survive on things like grubs and worms.

BASCOMB: You said that they're common roadkill, you know, armadillos, they're sort of like these little well armored tanks. I wonder if they can be dangerous at all as roadkill?

DYKSTRA: Not necessarily dangerous. There no match for a tire, and they just tend to be helpless out there by the side of the road.

BASCOMB: Oh, poor armadillo. Well, I hope they fare better in the north. Well, what do you see for us from the history books this week?

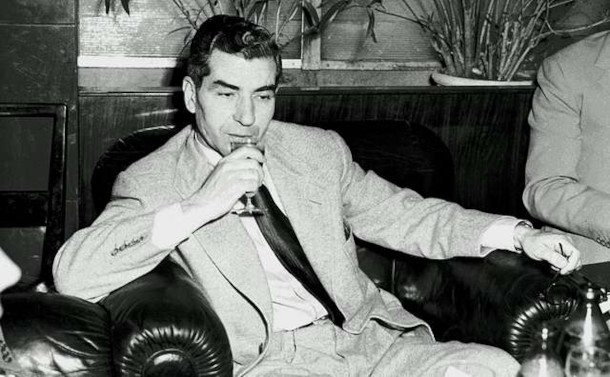

DYKSTRA: March 31st, 1929, big mafia boss Charles Lucky Luciano. He was said to head all of the mafia families in New York. He was successfully prosecuted the only time in his life for killing. And that killing wasn't a mobster or somebody in debt or a rival. It was a pheasant. An Ulster County New York Game Warden fined Lucky Luciano 50 bucks for shooting a pheasant out of season. That pheasant of course sleeps with the fishes. And Lucky went on to do his day-by-day supervision of killing for which he was never put in jail, not for murder.

Gangster Charles “Lucky” Luciano never served time for the human murders he facilitated, but he was caught for one killing: that of a pheasant. (Photo: Remo Nassi, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

BASCOMB: Well, that sort of reminds me of Al Capone that got put away for tax evasion. But of course, I don't suppose anybody's going to see prison time for shooting a pheasant?

DYKSTRA: No. Capone actually ended up doing serious time for that. Lucky Luciano did not. He eventually got caught on some other charges, but not for killing any human being.

BASCOMB: Well, thanks for sharing these stories with us, Peter. Peter Dykstra is a contributor for Living on Earth, and we'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, Bobby, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

BASCOMB: And there's more on the stories on the Living on Earth website. That's loe.org.

Related links:

- To read more about the distilleries’ decision to go net zero, read the original Washington Post article by William Booth

- To learn more about Armadillos' movement north, read about it on the Yale Climate Connections website

- You can read more about Lucky Luciano’s pheasant failing and his life story in Tim Newark’s book Boardwalk Gangster: The Real Lucky Luciano

[MUSIC: Darol Anger with Martin Hayes, “A Little Help From my Friends” on Diary of a Fiddler, Compass Records]

Natl Audubon Keeps Enslaver’s Name

A portrait of American ornithologist, naturalist, painter, slaveowner and white supremacist John James Audubon. (Photo: White House Historical Association, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: The National Audubon Society, formed in 1886, is one of the oldest environmental organizations in the United States. The bird conservation group was named after naturalist John James Audubon, author and illustrator of The Birds of America, widely considered one of the best ornithology books ever created. Mr. Audubon also bought and sold slaves, actively advanced research designed to boost the myths of white supremacy, and denigrated Native Americans and black people in his writings with the “n” word, even though some sources suggest his birth mother may have been of mixed race. The National Audubon Society recently voted to keep the name honoring Mr. Audubon despite pressure to distance themselves from his racist legacy. Several local chapters are in the process of changing their name, including the District of Columbia where Tykee James serves as President. Tykee has previously served on the government affairs team at the National Audubon Society and joins me now for more. Welcome to Living on Earth, Tykee!

JAMES: Thank you for having me, Steve. Always great talking with you.

CURWOOD: What did John James Audubon do that's so racist that you and many others think that his name needs to come off the society's masthead?

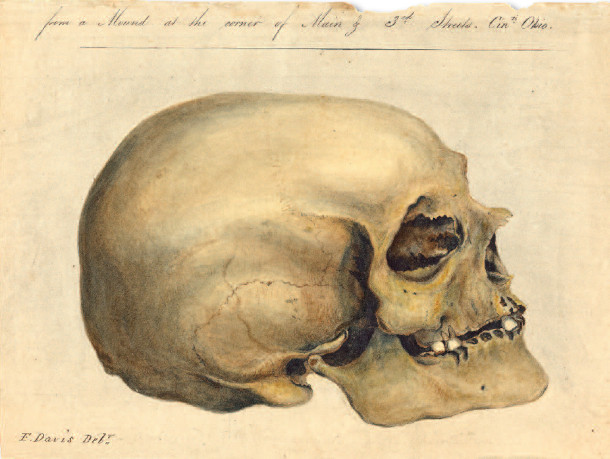

JAMES: The legacy of John James Audubon is based in enslaved Africans being enslaved upon his journeys and his perpetuation of indigenous genocide and he journaled and from his journals we can see what he thought we can see what he said about his own adventures. Using words that I wouldn't use to describe the people that he's around, that are black and indigenous. He's also used his position as a rich white guy in the mid 1800s, to make interactions with indigenous communities that led to violence and he collected a few skulls in that and not bird skulls, human skulls. What does it carry human skulls for? Not a guy that inspires from his work.

CURWOOD: I read someplace that John James Audubon worked with this guy Samuel George Morton, helping dig up bodies of black people to measure their skulls with the hypothesis that somehow the shape of skulls indicated that black people were inferior to white people.

JAMES: Well, I'm glad you brought that up, because it is an important reference to so many stereotypes and so many ways that folks understand race and how folks of different races are treated. A lot of it comes from that now you didn't have to study, you didn't have to go to any of Morton's classes to know this. But the belief that hypothesis, disproven, even though it was disproven and continuously can be disproven, that hypothesis is still carried in culture and in practices that we see today.

Lithograph from Samuel George Morton, Crania Americana. John James Audubon was among the scientists who stole human skulls from burial sites of Native Americans and Mexican soldiers. They sent the remains to Samuel George Morton, who used them in his racist science practices claiming that intelligence can be ranked by skull size. (Photo: F. Davis (engraver), Wikimedia Commons, University of Pennsylvania Museum, Public domain)

CURWOOD: Tykee what was your reaction when you learned that the National Audubon Society leadership had decided to keep the name, despite the rather loud sound of folks who are saying it's time to get rid of it?

JAMES: I first thought, okay, they did not consult chapter leaders, they did not consult members and it's in their statement. You know, it would've been very different if in their statement they had, we've heard overwhelmingly from members we've heard overwhelmingly from chapter leaders, and this is what we decided, no, they said, we talked to a couple people when we made this decision, and by the way here's 25 million to shut up about it. But after some digestion, I've reflected on the fact that it's one thing to inherit the name, right, I inherited the name when I took over part of the leadership at DC Audubon, I inherited the name, but I am not endorsing it, by choosing to keep it, I am not promoting it further by choosing to keep it. There were so many people who have been and hopefully still are rooting for the currently named National Audubon Society to see this differently at some point. And I honestly think it's a leadership decision, not a decision that represents the community, not a decision that represents the workers. And in fact, the workers who have organized their own union, I've helped organize it, now are calling themselves Bird Union as a placeholder name so that they can go through their own process of renaming an organization within the organization that better reflects their values and ambitions. The reality around seeing what inspires us is the important part of this because they talk about how the name is synonymous with bird conservation, I don't believe that for one second, I don’t believe that not for one minute. Maybe for a certain demographic and then that's, of course, what gets into why I see this as a leadership decision. Most of the people on the board, as well as in leadership, are old white folks. Who will google Audubon near me to find a local chapter, same demographic. And if that's a name that folks are familiar with, from a certain demographic, there's something that we should reflect on if that's also the reflection of their leadership, because that then doesn't possess an endorsement from the current or next generation of leaders that they're seeking to inspire and stay relevant to.

CURWOOD: You referred to the National Audubon Society's $25 million commitment over five years to fund equity diversity and inclusion and belonging work, which they announced the very same day that they were keeping the name Audubon. I mean, to what extent do you think that commitment makes up for the fact that they're keeping the Audubon name in your view and to what extent does it tell you that this is to please certain key donors?

Portland, Oregon’s Audubon chapter is among the many organizations moving away from the name Audubon due to the racist legacy it upholds. (Photo: Finetooth, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

JAMES: This is definitely about that but I also think that the $25 million being mentioned specifically on that day is easily one of the best, I hope it gets nominated for best performance of wokeness of 2023. You read their statement and I really encourage everybody to read it. It reads as discrete thoughts, not as a flowing document, it reads as like every person got one paragraph to say one thing about it. The lack of transition shows how short sighted a decision this is. This is very short sighted for an organization that wants to be relevant to the current generation and the next. There is no amount of money that can distract us from the additional wrongdoing that's taking place in that leadership at that organization. Mind you, what organization what company would make an investment in a department that hasn't had a department head for more than a year, for the last four years. They hadn't had somebody in that position for over a year. Twenty-five million dollars, zero leadership in that position. The workers have been doing the work, don't get it twisted, the workers have been doing the work. But if you don't have a vice president of equity, diversity and inclusion, and you're putting $25 million in it, is that $25 million gonna find somebody to lead it? Or is this going to be led by the same folks who chose to keep the name?

CURWOOD: Describe for me a bit of what is the work that you're talking about here? Why is Audubon important? Why is this work important?

JAMES: I've been watching birds for about a decade and when I worked at the National Audubon Society, I helped organize bird walks with members of Congress and congressional staff. I see that from my neighbors in West Philly, to congressional staff on the hill, everybody has a story about birds. And those stories about birds can be very powerful motivators to protect them and the places they need. Less stories about birds means we have less protectors. So to get more of those stories, let's make space for those stories because everybody has a story, but not everybody has a space for it. And I hope that organizations like the National Audubon Society, with all the potential it has for good realizes that it can still change its name and keep the mission. That's something that I think everybody will support.

CURWOOD: So what's your understanding of why they want to keep this name? I believe the National Audubon Society went on the record not so long ago, calling or at least joining the call for the removal of Confederate monuments that, of course are based on racism.

JAMES: You know, it gets back to the point I made earlier. If knowing better means doing better you don't have to do better if you don't feel like you're going to be held accountable. National Audubon Society, their leadership, they do not feel like they can be held accountable and I am very disappointed in that but not surprised. I've been part of the chapter network for a pretty long time I've been talking to other chapter leaders and a lot of us are taking our own steps towards renaming. DC Audubon is going through the process, Seattle Audubon is leading very, very well. Madison Audubon, Chicago Audubon, New York City Audubon recently just announced, Portland as well. So there are folks realizing that this Audubon name whether you're affiliated with National Audubon Society or not, this Audubon name has to go. There's no reason to keep this.

This sketch of the Louisiana Heron is amongst the many featured in John James Audubon’s most famous book, Birds of America. (Photo: Rawpixel Ltd., Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: To what extent do you think that national Audubon's reluctance to let go of the name of this rather extreme and enslaver? If one looks closely at his record, he just wasn't sort of casual, he really was associated with people that had deeply racist beliefs. To what extent do you think that inhibits the mission of bringing more people into the birding community in the environmental movement? I mean, we've seen over the last 70 years a decline of 70% of the populations of animals across the board, birds populations are really crashed. So to what extent does this get in the way of getting more people to bird to become more defenders of bird to understand and participate in what I think you have called a time's the magic of birding?

JAMES: If you have to become a branded ambassador to an enslaver to protect the things and places you care about most, we are not achieving environmental progress. I believe firmly that there are no casual enslavers. That being said there are no casual enslavers. If you are taking away somebody's liberty and your legacy is based off of that, your family's wealth is built off that, this country's wealth is built off of that, well there's something that we need to examine in that, there's something that we need to look at and it's not just renaming things. It's disrupting the status quo. And at the end of the day, at the beginning of the day, we can't forget the effects that slavery has had on where we are today, you know, the aspect of Morton and pushing the hypothesis that brain size is intelligence and therefore there's an attachment to skin color, like that whole racial classification system that's been found false 20 ways to Tuesday, but why it remains in the culture it's because people don't always know where those ideas come from. So it's important to know where things come from because if you're just trying to attack this tree of evil, not good and evil, not even knowledge, just just evil and you're just pruning the buds you're not going to get to the root of the issue. So if you see me playing in the dirt, I'm not there to have fun, I’m trying to uproot this issue, and ignoring that, that's where National Audubon Society is.

CURWOOD: Tykee James is currently serving as president of the Audubon Society of the District of Columbia, and previously served on the government affairs team at the National Audubon Society. Thank you so much for taking this time with us today, Tykee.

JAMES: Thank you, Steve looking forward to talking to you again.

CURWOOD: National Audubon has said a name change would divert resources from their mission. Their full statement is on our website loe.org.

Related links:

- Smithsonian Magazine “National Audubon Society Votes to Keep the Name of an Enslaver”

- Follow Tykee James on Twitter

- Audubon | “National Audubon Society Announces Decision to Retain Current Name”

- Learn more about Tykee James

- Crosscut | “Amid Controversy, Seattle Audubon Changes Its Name”

- The Guardian | “Bird Union Drops Audubon Name to Distance from Namesake’s Racist Past”

- Common Place | ““WE LEFT ALL ON THE GROUND BUT THE HEAD”: J. J. AUDUBON’S HUMAN SKULLS”

- National Audubon Society Statement

[MUSIC: Jacqueline Schwab, “La Paloma (The Dove)” on I Lift My Lamp: Illuminations From Immigrant America, by Sebastien Yradier/arr.Jacqueline Schwab, Sono Luminus]

BASCOMB: Coming up – It is likely the next breath you take is loaded with nano particles of plastic that pose risks to your health. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Hubert Laws, “Moonlight Sonata:” on My Time Will Come, by Beethoven/arr.Hubert Laws, Music Masters Jazz]

Microplastics – “A Poison Like No Other”

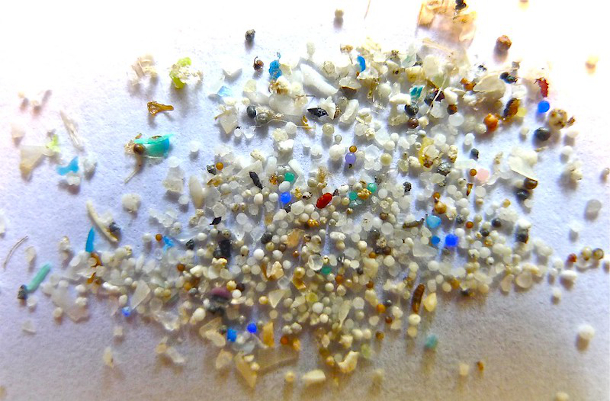

Microplastics from the Chesapeake Bay watershed are pictured in a laboratory. (Photo: Chesapeake Bay Program, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

Plastic is ubiquitous in modern life, plastic bags, plastic furniture, plastic playgrounds. Even most of our clothes are now made of plastic fibers. But a lot of the plastic surrounding us is so small you probably don’t see it. Microplastics are literally everywhere scientists have looked for them: from the deepest ocean trenches to mountain peaks, in our air, water and food, even in our own bodies. And most plastic is made from a cocktail of thousands of chemicals which can cause unknown harms to both our health and the health of the ecosystems they contaminate. In the recent book “A Poison Like No Other: How Microplastics Corrupted Our Planet and Our Bodies” science journalist Matt Simon takes a deep dive into the world of microplastics and what we can do to stop them. Matt Simon, welcome to Living on Earth!

SIMON: And thank you for having me.

BASCOMB: So why do you consider microplastics "A Poison Like No Other," as is the title of your book?

SIMON: I mean that I think in two forms. So by one kind of metaphorical sense of poison, I'm talking about this material that has corrupted essentially every corner of the environment. It is in the air, it is in the land, it's in the sea; absolutely everywhere, so a widespread kind of material in that poisonous sort of sense. But I also mean poison in the classical toxicological sense, that this is a very complicated material, and a very toxic material, that has at least 10,000 different chemicals in it, a quarter of which scientists consider to be of concern, meaning it's either straight up toxic or persistent in the environment or in organisms. But plastic's this weird sort of poison and pollutant in that it's this physical thing in the environment. It is something that can get up in the atmosphere and change cloud formation; it is something that organisms that are small enough can swallow and choke on. In addition to that, as these particles are flying through the environment, floating through the environment, they are picking up this really complicated community of bacteria and viruses. So it's this, unlike a classical poison, like mercury, or lead, which is just an element, obviously neurotoxins, this is far more complicated. And scientists are just beginning to come to grips with it.

Microplastics contain and can leach the 10,000 or so different chemicals that plastics are made of. (Photo: 5Gyres, Oregon State University, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

BASCOMB: You write in your book that there have been studies done showing that when people just walk through a room, they're literally bringing with them a wave of microplastics, you know, sort of depositing it in the air.

SIMON: I call it the "Pigpen effect" in the book, so Pigpen from the "Peanuts" comics: this perpetual, swirling aura of dirt and grime; we are doing the same thing with microfibers. So two thirds of clothing is now made out of plastic, I don't think very many people realize that. So polyester, nylon -- that's all plastic. It's very soft plastic, but it comes apart, both when it's being washed in a washing machine, but also, as you say, as we're walking through the environment. There was one calculation that we are shedding something like a billion of these fibers a year, just by walking around. And because we spend 90% of our time indoors, a good amount of that microplastic is settling on the floors of our homes. And scientists are finding that we are inhaling a lot of those particles every day. By one calculation, it's 7,000 particles that we inhale a day. And we know virtually nothing about the potential human health effects, other than to say that this is certainly not a good thing to have in the body.

BASCOMB: I mean, inhaling 7,000 a day; and, you know, the particles that we're talking about here are extremely small, hence the name microplastic. And you write in your book that any calculation that you can make is immediately outdated, because we're always creating more plastic, there's always going to be more microplastic introduced to the environment. But is there any way to quantify how many pieces of microplastic we're talking about here? Or, you know, give us a scale; or, I think the number is too big even to really understand. But can you compare it to anything that would you know, be real for our listeners?

An illustration representing the breakdown of a plastic bottle in the ocean into smaller microplastics and nanoplastics that are then eaten by fish. “Think of those macro plastics, like bottles and bags, as pre-microplastic,” Matt Simon says. (Image: European Environmental Agency, Wikimedia Commons public domain)

SIMON: Yeah, so when we're talking about microplastics as defined by scientists, these are bits that are smaller than five millimeters. And that's about the width of a pencil eraser. So that's actually a microplastic you can see with your naked eye, and actually, if you look through a window in your home, and the sunlight is coming through it at sunset or sunrise, and you see little bits of things floating around, there's a good chance that a lot of those are actually plastic microfibers coming from bed sheets and clothing, carpeting, those sorts of things. But scientists are now getting better at detecting nanoplastics, and nanoplastics are far smaller. There's some debate over there what the threshold should be, but it's typically around a millionth of a meter. These nanoplastics are very, very tiny. And scientists are finding consistently -- it's still difficult and expensive to test for them, but when they do in the environment -- they're finding way, way more nanoplastics than microplastics. There was one study that looked at a remote mountaintop in the Alps, and detected for nanoplastics, these very, very tiny ones and found that if you were standing on the top of this mountain, just by standing there for a little while, you would have millions of these nanoplastics fall on your shoulders. That's outdoor air. So the atmosphere is thoroughly saturated with nanoplastics in numbers that are just difficult to comprehend. The frontier is, okay, well, when it comes to inhaling all those particles, how much is going to be too much to have in the human body? We don't want any of them. But when does it become a problem? And we'll see those studies probably in the next five or 10 years.

BASCOMB: Well, what do we know so far about the human health impacts of microplastics and micro fibers?

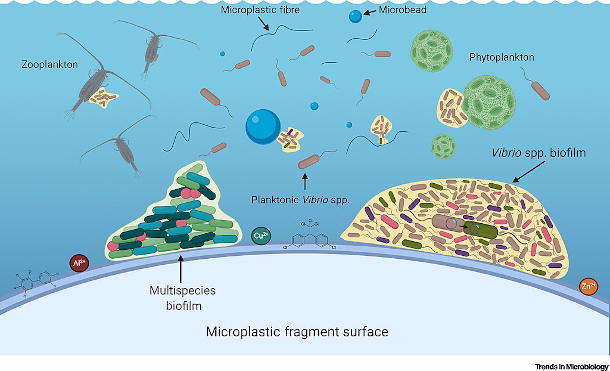

A graphic depicting surface microbial interactions with microplastics compared to zooplankton and phytoplankton (Image: Jake Bowley, Craig Baker-Austin, Adam Porter, Rachel Hartnell and Ceri Lewis, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 4.0)

SIMON: So we are getting early studies on mouse models, in particular where you know you feed these mice microplastics or make them inhale the microplastics. And they're actually showing that these particles, especially the very small ones, can readily move through our tissues. Which is not surprising, because we are finding microplastics in human blood, and human lung tissue and guts, we are finding them in placentas, but also in the first feces of newborns, which means that these newborns are exposed to microplastics while they had been in their mothers, so these particles are crossing barriers. And it's not any surprise, because nanoplastics get down to a size where they're able to penetrate cells. And we have seen in a couple of studies that exposing human cells in the lab -- not exposing people, to be clear, you can't dose people with microplastics, just ethically -- but exposing cells themselves is highly, highly toxic.

BASCOMB: Well, you mentioned newborn babies with microplastics in their bodies, and you write in your book that babies and young children are particularly susceptible. Can you tell us more about that? Why are young children particularly of concern?

SIMON: The primary concern here is a group of chemicals known as endocrine disrupting chemicals, or EDCs. There are a bevy of these in plastics. The most famous one is BPA, which has been largely phased out because it was linked to any number of, of human health problems, cancers in particular. That is one of just many EDCs that we have in plastics. When we're considering these EDCs, they mess with the hormone system. And for children in particular, you do not want that. You especially do not want that, because we know that fetuses are exposed to microplastics in the womb, this is a very delicate time. It's this, I talk about it in the book as this kind of, this ballet, this intricate dance of so many of these hormones kicking off in sequence to build a healthy human being. But then, you know, when a kid is walking around the home, a toddler is toddling around on the floor, they are down to the level where so many of these fibers are settling. So EDCs, these are the groups of chemicals that scientists are mostly concerned about in plastics just because they are mucking with these very delicate hormone systems in the human body.

Microplastics on a beach (Photo: Vera Kratochvil, public domain CC0 license)

BASCOMB: And you write in your book, babies that are fed formula -- it has to be made with hot water, perhaps in a plastic bottle, and the action of shaking it, you know, is also releasing a lot of microplastic.

SIMON: This is a pretty scary study that came out a couple of years ago; perhaps not surprising, I think scientist knew for a long time that these are the forces that are best able to break apart plastic. If you are preparing hot liquid in plastic, and then shaking it up, you are providing exactly the sorts of things that do break apart plastics, which are these, of course, very tough chemicals, but they're not invincible. So these scientists showed that a baby might be ingesting a million of these particles a day. But coming back to this idea that they were looking for a certain size range of these plastics, they were not looking at nanoplastics. And it's likely much, much more nanoplastics, again, at this extremely delicate period of human development.

BASCOMB: So it's obviously very harmful to people and to the natural environment. You know, we've all seen images of sea turtles strangled by six pack rings, or seabirds with their stomachs full of plastic, and they're awful. But those are macro plastics, you know, large pieces of plastic that we can identify. But what about microplastics in the environment? Can you share a few examples of the kinds of impacts they're having on, you know, animals and ecosystems?

“Mr. Trash Wheel” is a floating garbage scooper that’s helping intercept plastics and other garbage in Baltimore, Maryland’s inner harbor. (Photo: Dicklyon, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

SIMON: First of all, I think it's really important to think of those macro plastics, like bottles and bags, you know, a turtle choking on a plastic bag, that is essentially pre-microplastic, is I think a good way to think of it. Any of those plastic products are going to break down over time into microplastics and nanoplastics. So when they do eventually disintegrate, they haven't disappeared, they've just deconstructed into sort of this galaxy of particles that then float around the ocean. So macro plastics are not available to a tremendous amount of sea creatures, right? So like a whale or a dolphin or a turtle is able to choke on these things, but there are vastly more smaller creatures in the ocean that are able to choke on microplastics. So primarily, this is the planktonic community. So you have phytoplankton, which are little plant-like organisms that grow on the surface. Those are eaten by zooplankton, these little tiny animals. It's this very delicate food web where that then goes on to feed everything else. So fish larvae feed on those zooplankton, the larvae themselves become food for bigger fish, and on and on. Scientists have been finding that these zooplankton, little crustaceans and things like that, readily eat microplastics. These are just the right size to kind of jam into these tiny digestive systems. So there are two concerns here. One is that these creatures are filling up their stomachs with microplastics, and that decreases their appetite for actual food, so they starve to death. The other is that you have these plastics breaking apart further in their digestive systems and leaching out the component chemicals -- again, 10,000 of them, any one of which might be toxic to a particular organism.

BASCOMB: You know, the Earth is really good at cycling energy, you know, we think of ocean and atmospheric currents like the Gulf Stream or the jet stream, and you write here about how microplastics are really getting taken up in those currents to get transported literally everywhere scientists have looked for them. Can you tell us a bit about that, please?

The after-market microplastic filter attached to author Matt Simon’s washing machine. (Photo: Matt Simon)

SIMON: In the ocean, it probably shouldn't come as any surprise, really, that we're finding these microplastics, you know, up and down the water column here in the ocean. They are finding extreme amounts of these plastics in the Mariana Trench, one of the deepest points in the ocean; it has gotten absolutely everywhere, because it is a fundamental part now of this carbon cycle. Creatures eat these, they poop them out, they sink, other creatures eat them, they sink, and it's gathering in these ocean sediments. And it's important here to not think of these as separate systems, right? So the ocean is not at all a separate entity from the atmosphere. And scientists are showing in fact that when bubbles come up in the ocean, they gather microplastics, and pop at the surface and actually fling those microplastics into the atmosphere. And that then blows onto land as a sea breeze. And that is part of the reason why the atmosphere is so thoroughly contaminated with microplastics, because it's basically burping out of the ocean. That then is flying around in, essentially, atmospheric currents, as it is in the ocean. They are so light, these microplastics, so tiny, they very readily get everywhere.

BASCOMB: So we know of course, that plastic is made from fossil fuels. And it's widely considered to be the the fossil fuel companies' Plan B, if we're going to move away from combustion engines and you know, fossil fuels for energy. Can you talk a bit about that, and the trajectory that we're on for creating more plastic going forward?

Matt Simon is a science journalist at Wired magazine, where he covers the environment, biology, and robotics. He’s the author of “A Poison Like No Other” and two other books. (Photo: Jenna Garrett)

SIMON: These companies have really made no secret about the writing on the wall, as they see it, and as we all see it: that we're going to decarbonize our economy at some point. We're going to move away more and more from fossil fuels into renewables. And what these companies -- these are the same companies, basically, these fossil fuel companies, petrochemical companies, it's all the same crew -- they are massively shifting their production into plastics, tripling production, perhaps by the year 2050, because that's their source of revenue going forward. All along the supply chain, we have issues with climate change and these plastics, and in these interesting ways, once they get out into the environment as well, there has been research showing that as microplastics degrade in the environment, they release methane in particular, which is a extremely potent greenhouse gas, something like 80 times more powerful a planet warmer than carbon dioxide. So now we have to consider, there is so much of this stuff in the atmosphere. How much of this it is actually off gassing? How much methane is it contributing to global levels? There's a calculation that if we have this exponential increase in the production of plastic by 2050, the emissions inherent in that will be equal to 600 coal fired power plants, which is a lot. It's a lot of carbon. And that's the injustice here, is that as we're actually making good progress as a species decarbonizing, switching to renewable energy, decommissioning coal plants in the United States and elsewhere, we're having the rise of this separate source of emissions in plastics. This is an emissions intensive industry, and as it grows exponentially, so too, will the emissions.

BASCOMB: How do we, you know, adequately think about really tackling this problem? I mean, it's ubiquitous, plastic is everywhere; it's all things, we all use it. I mean, where do you even begin to really address this issue?

“A Poison Like No Other: How Microplastics Corrupted Our Planet and Our Bodies” (Image: Island Press)

SIMON: At the end of the day, the only way we're going to fix this problem is to just stop producing so much plastic. There is no substitute for that. You've probably heard of the ocean cleanup -- a giant plastic catcher in the Pacific Ocean -- rather silly, in my opinion, and the opinion of a lot of plastic scientists, that it's too late at that point. We need to stop these plastics from getting out there in the first place. So the farthest upstream we can go is stopping producing so much plastic. That is the only thing that's going to fix this; that is roundly agreed upon by plastics activists and plastic scientists. We can go a little bit farther downstream; a really fun and very useful piece of technology is called "Mr. Trash Wheel." It is a barge in Baltimore Harbor that has big googly eyes. It's absolutely adorable, but it's also very useful. It catches a lot of this plastic floating out to sea before it can get to sea. And then when it comes to mitigating something like the microfibers from our clothes, perhaps millions of these fibers break off in a single load of laundry and then flush out to a wastewater treatment facility. 10% of those fibers are flushed out to the ocean, where they of course go on to get into the stomachs of these zooplankton and other sea creatures, but 90% is sequestered in sludge, which is human waste applied as fertilizer to fields. So we're applying concentrated microplastics to our crops. So what we need, then, is filters on washing machines, right? Unfortunately, don't have those in the United States, we have filters on our dryers to catch the lint. But what you can get right now is an aftermarket filter for your washing machine. I have one at home, and it seems to work pretty well. I mean, it's fantastic that we do individual things. And I think that can add up into something actually very impactful if, you know, you tell your friends about microfiber filters on washing machines, maybe we all get one. But we need a mandate, a government mandate that all washing machines that come off the line have to have these filters. And France is actually the first to do this. They're requiring that by 2025, all machines have to have filters. So that needs to happen in parallel to extreme urgency in bringing down the production of plastic, because there is absolutely no substitute for that.

BASCOMB: Matt Simon is author of "A Poison Like No Other: How Microplastics Corrupted Our Planet and Our Bodies." Matt, thank you for your time today.

SIMON: Thank you for having me. I appreciate it.

Related links:

- Find the book “A Poison Like No Other: How Microplastics Corrupted Our Planet and Our Bodies” (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

- A recent article on microplastics in the ocean by Matt Simon

- Author Matt Simon’s website

- Learn more about “Mr. Trash Wheel”

[MUSIC: 2Cellos, “Halo” on Dedicated, by Beyonce/arr.2 Cellos, Sony Masterworks]

CURWOOD: Next time on Living on Earth, a legal battle for civil rights and environmental justice for black communities in Louisiana’s "Cancer Alley".

HARDEN: Oh my gosh, you can talk to any person in St. James Parish, and residents can tell you about chemotherapy treatment that they're taking, or doctors trying to figure out and diagnose a particular health problem that's affecting their liver, or kidneys. Asthma is a huge problem, especially for children. You name it, in terms of what is scientifically known about the toxic chemicals raining down on people in St. James Parish, you will see those health effects show up in the symptoms suffered by the residents.

CURWOOD: Now residents are fighting back in court. Hear that next time on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: 2Cellos, “Halo” on Dedicated, by Beyonce/arr.2 Cellos, Sony Masterworks]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Fern Alling, Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Iris Chen, Josh Croom, Jenni Doering, Swayam Gagneja Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Jusneel Mahal, Louis Mallison, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari.

BASCOMB: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments at loe dot org. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood, thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth