June 23, 2023

Air Date: June 23, 2023

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

EU Bans Deforestation Products

View the page for this story

The European Union has enacted legislation aimed at reducing global deforestation with a ban on the sale of products made from cattle, cocoa, coffee, palm oil, soya, and wood, produced on land deforested after 2020. Anke Schulmeister, the Senior Forest Policy Officer for the World Wildlife Fund joined Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering to explain. (09:19)

An Introduction to Queer Ecology

View the page for this story

The academic discipline known as “queer ecology” looks at environmental politics through a queer lens, rejecting heterosexual and cisgender identities as the only norms. Host Aynsley O’Neill speaks with Cate Sandilands, who coined the term ‘queer ecology’ in the 1990s, about diverse displays of gender and sexuality in nature, as well as how queer resistance can make an impact in the fight against the climate crisis. (07:48)

BirdNote®: The Power Of Albatross Partnerships

/ Wenfei TongView the page for this story

Raising a chick is no small feat for Albatrosses and both parents play a vital role. BirdNote®’s Wenfei Tong describes the strong and unique bonds that help albatrosses raise their young. (02:07)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Living on Earth Contributor Peter Dykstra joins host Aynsley O’Neill to discuss how a batch of hastily crafted hand sanitizer inadvertently released toxic chemicals like the carcinogen benzene. Also, how outdoor activities during the summer are moving indoors due to increasing temperatures from climate change. They follow with REI and Dick’s Sporting Goods banning PFAS forever chemicals in their products. And for history, after a 1907 decision by President Theodore Roosevelt the Owens Valley water was diverted to serve Los Angeles, eventually leaving the valley dry. (05:35)

Danger Days

View the page for this story

Poet Laureate of Mississippi Catherine Pierce describes these days of extreme heat and humidity that are changing summer vacation as the planet warms in her book Danger Days. (02:34)

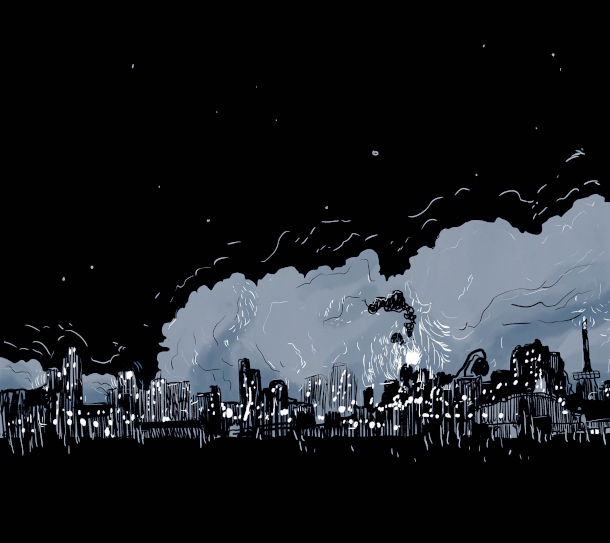

Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands

View the page for this story

The Athabasca oil sands in Alberta; Canada ranks as one of the world’s most destructive crude oil operations. People laboring in the Athabasca oil sands often live in austere work camps, with long 12-hour shifts and female workers imperiled by sexual harassment and violence. Kate Beaton captured that painful reality in her 2022 graphic memoir Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands and joined Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering to talk about her experience. (17:03)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

230623 Transcript

HOSTS: Jenni Doering, Aynsley O’Neill

GUESTS: Kate Beaton, Catherine Pierce, Cate Sandilands, Anke Schulmeister

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Wenfei Tong

[THEME]

O’NEILL: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

O’NEILL: I’m Aynsley O’Neill

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

The European Union has a new law that requires coffee, chocolate and more to be deforestation-free.

SCHULMEISTER: If you ask me, I do think that this law is a game changer, but this law will only be successful if it is properly enforced and implemented. That means there are enough controls, there is prosecution if there is a breach of the law detected and we can then keep deforestation off our plates or out of our supermarket shelves.

O’NEILL: Also, a firsthand account of life in the Alberta oil sands.

BEATON: How would you feel if people around you were contracting these rare cancers, and the government was trying to deny it, and the corporations were not claiming responsibility, and then they went out and made a gigantic fuss about these ducks? And everybody cared so much about the ducks?

O’NEILL: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

EU Bans Deforestation Products

Deforestation in Brazil from palm oil development. (Photo: Miguel Pinheiro, CIFOR, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

O’NEILL: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston this is Living on Earth. I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

The European Union is speaking for the trees, at least with a new policy. Its 27 member countries recently adopted rules aimed at reducing their contribution to global deforestation. According to the World Wildlife Fund the EU is one of the world’s largest importers of goods from tropical deforestation and associated emissions, second only to China. So the EU Deforestation-Free Regulation will block certain products from entering the European market if they have been produced on land deforested after December 31st, 2020. Members of the EU will need to inspect imported products and turn away non-compliant shipments, and they’ll also check the compliance of goods produced within the EU itself. Anke Schulmeister is a Senior Forest Policy Officer for the World Wildlife Fund and joins us from Brussels to explain the new anti-deforestation law. Welcome back to Living on Earth Anke!

SCHULMEISTER: Yeah, thank you so much for inviting me again.

DOERING: So, can you give me an example of a product sold in the EU that might be affected here.

SCHULMEISTER: So, it could be the steak for dinner. It could be the chocolate for either in your hot milk or with your hot coffee, it could actually be even the coffee that you are taken for breakfast, or for lunch.

DOERING: So which countries are the producers of these kinds of products like palm oil, beef, soy, cocoa, coffee, and wood that could be affected by this EU deforestation law?

SCHULMEISTER: Yeah, I think there could be quite a number of countries are affected. So for example, the biggest producers of palm oil worldwide are Indonesia and Malaysia. But we also have big slide producers like Brazil, Argentina, or also the United States who do that. And we also produce even some soy here in the EU. For Cokoa we have countries in Latin America, but also in Africa. Timber is US also a lot, it is also in China and in the EU itself. I mean, the products come from a lot of different places all over the world.

DOERING: So how will companies be able to actually prove that their products weren't involved in leading to deforestation?

SCHULMEISTER: So the companies would need to use a system that is called due diligence. What due diligence means is that companies need to assess the risk on whether a product that they would like to place on the market in the EU can be linked to deforestation or not. If their analysis comes to the conclusion, that there might be a risk, they would need to take measures to mitigate this risk and if this risk cannot be mitigated, then they will not be allowed to place this product on the market. What is important to understand this that this law applies before a product is placed on the market. If for example, there is a big soy shipment coming to the EU, this will be checked by the customs authorities, you know, they will look into the information and they will decide whether this ship can then be unloaded or not.

Deforestation near Yangambi in the Democratic Republic of Congo. According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization around 10 million hectares of forest are cut every year contributing to biodiversity loss and speeding up climate change. (Photo: Axel Fassio, CIFOR, Flickr, CC-BY-NC-ND-2.0)

DOERING: Also, a company might be able to say that a product came from this particular plot of land. But is there any other way of really identifying and verifying that that is in fact the case?

SCHULMEISTER: Yeah, so to determine these plots of land, companies will need to provide geolocation data. So they will actually provide the longitude and latitude data on where these products were produced. What that means is that you could imagine, it's like being a big map of all the plots of land that you are sourcing your products from, which can then be checked via satellite imagery. So they see has the land being converted after a certain date. So that makes the verification easier.

DOERING: We hear a lot about the deforestation happening in the Amazon, or in Indonesia, or increasingly these days in the Congo, which is another huge tropical rainforest. How might these regulations help ease deforestation pressures in those places?

SCHULMEISTER: Yeah, so this legislation also has an article that really clearly talks about cooperation with producer countries. So countries that are producing these kind of products, they set up a specific so called strategic framework, to support those countries to address the underlying causes for this deforestation and also to help small holders, so small farmers and others to comply with the demands of the legislation. But we also need to keep in mind, this legislation is not a one size fits all solution, it needs a lot of other complementary measures to really address the global problem of deforestation.

According to the Union of Concerned Scientists wood production causes 380,000 hectares of deforestation annually. (Photo: Codie, Flickr, Public Domain)

DOERING: Anke, can you give me examples of products that could be produced in a forest on forest land without degrading the forest without requiring the forest to be cut down? I mean, I'm thinking of shade grown coffee, you know, we hear about that as a way to both preserve the forest and a way for people locally to make some money off of the forest. Are there any other examples like that, that would still comply with these rules?

SCHULMEISTER: I mean, when we look at the degradation perspective the definition that is in the new law, only covering part of what degradation is, so degradation could be you still have the forest standing, but you have cut so many trees that it has lost some of its functions. But that does not mean that you cannot cut certain timber out of a forest. If it keeps all the functions and if the forest is still resilient, again, this could very well be placed on the market. So for example, the timber that you would like to have for your kitchen table. And I think maybe another element which for us at WWF is very important, but which unfortunately we did not get in this legislation, is this law only applies currently to forests but it does not apply to other ecosystems, but the conversions or the destruction of other ecosystems is also very important and at the moment, very much going on. So as we speak the Cerrado, which is a savanna, so the mix of grass and woodland in Brazil has the highest rate over 80% more that was converted of that area than it has been in the May last year and that is quite a number. And that means that even if you protect the forests, we might have an effect a negative effect that it moves into other areas, and that should be stopped. And therefore, we need to make sure that we also include in this new legislation, other ecosystems and other wooded land and the first review to include potentially other wooded land would take place in a year's time.

DOERING: Anke, I understand that over 1,000 indigenous rainforest communities actually still exist and of the world's 300 million indigenous people 50 million live in or depend on tropical rainforests. So deforestation has a major impact on indigenous communities. How would this law connect with that issue?

Cacao is one of the products impacted by the new EU deforestation law. According to the Center for the Promotion of Imports from Developing Countries, Europe's total imports of cocoa beans amounted to 2.2 million tons in 2021. (Photo: Peter Burka, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

SCHULMEISTER: Yeah so this legislation actually also has elements that says that products cannot be linked to conflicts with indigenous and local peoples but it puts this on the level of national law. So what the law says is products to be placed on European market have to be free from deforestation, and need to be produced by respecting the national laws of a country of origin. So looking at this national framework, the respective national framework of a country with regard to indigenous people, so their land rights, their claims, will need to be taken into consideration and be checked by the companies. What we however, are missing a bit is that this law does not make any links to the international conventions. So, if a country did not sign up to or implement this national conventions and put them into national law, this will unfortunately not be covered by the legislation. That is a challenge, because we know that in a number of countries, there are disputes about lands to indigenous peoples, sometimes with the government and I do think that we need to really look into this. However, companies in their risk assessment will also look into this, they will need to look into are indigenous or are communities in my area, do they have claims? Are those claims justified? And did we talk about free prior and informed consent? Was a discussed with those people upfront on what shall happen on certain lands? So, it is not addressed as thoroughly as we would like it to be, but it is addressed.

DOERING: And why adopt this law now? Why is the EU making this move at this moment?

SCHULMEISTER: That is a very interesting question. So think the move at this moment comes also after long years of negotiation and preparation. So I've been working quite a long time on this legislation more than 10 years. So I think it's the accumulation of a lot of work from different stakeholders. But why now it is, I think also because we are seeing more and more the pressures on those precious forests and the impacts can be felt across the world. We should not forget that if there are no good forests left, no timber that you can export. If the soy is on a soil that is totally dry and has no more value, then there will be less harvest. So I do think in a way to keep in mind that things are changing and I do think that is one of the reasons why the commission acts now. But of course, what we do hope that this law is going to do it's set an example for other regions for other countries to also look into; how can I address my impact on deforestation?

DOERING: Anke Schulmeister is a Senior Forest Policy Officer for the World Wildlife Fund. Thank you so much, Anke.

SCHULMEISTER: Thank you so much. It was lovely to speak to you again.

Related links:

- European Commission | “Green Deal: EU Agrees Law to Fight Global Deforestation and Forest Degradation Driven by EU Production and Consumption.”

- Council of the European Union | “Council Adopts New Rules to Cut Deforestation Worldwide.”

- Thomson Reuters | “Implications for Global Trade Professionals as EU Legislation Seeks to Limit Deforestation.”

[MUSIC: Bela Fleck & Edgar Meyer, “Bug Tussle” on Music For Two, by Bela Fleck, Sony Classical]

O’NEILL: If you enjoy the stories you hear on Living on Earth, please consider signing up for our newsletter. You’ll never miss a show, and you’ll have special access to show highlights, notes from our staff, and advanced information about upcoming live virtual events. The Living on Earth newsletter is sent to your inbox weekly. Don’t miss out! Subscribe at the Living on Earth website, loe.org That's loe.org. By the way, you’ll also find photos, links to more information and a full transcript of every single show there. For even more LOE, follow us on Instagram – we’re @livingonearthradio. We tweet from @livingonearth, and our Facebook page is Living on Earth. And we’d love to hear from you! You can write to us any time at comments@loe.org that’s comments@loe.org.

[MUSIC: Bela Fleck & Edgar Meyer, “Bug Tussle” on Music For Two, by Bela Fleck, Sony Classical]

O’NEILL: Coming up, how “danger days” of extreme heat are forcing summer activities indoors. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Peter Calo, “Oh! Dem Golden Slippers” on Cowboy Songs, Traditional American/arr.Peter Calo, Tune Stew, a division of North Star Music]

An Introduction to Queer Ecology

White mulberry trees have been known to change sex, from male (those that produce pollen) to female (those that produce fruit) and vice versa. They also sometimes produce fruit and pollen from the same plant. (Photo: Luis Fernández García L. Fdez, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.1 ES)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

June is Pride Month in the United States, a time to celebrate the LGBTQIA+ community. That’s a group that includes lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or questioning, intersex, and asexual people. So we wanted to take a look at some of the diverse displays of gender and sexuality that are found in nature. For example, take the New Mexico whiptail, an all-female species of lizard that reproduces asexually. Or consider the seahorse, where the female partner lays the eggs that the male partner becomes pregnant with. While situations like these break our societal norms of gender and sexuality, that doesn't make them any less natural, and that’s one of the key themes of the academic discipline known as "queer ecology". The idea of "queer ecology" connects the worlds of queer theory and environmental politics, by examining the environment through a lens that rejects heterosexual and cisgender identities as the only norms. Cate Sandilands is a writer, scholar and professor in the faculty of Environment and Urban Change at York University in Toronto. She originally coined the term “queer ecology” in the 1990s and she joins me now. Thank you for being here, Cate!

SANDILANDS: Thank you very much Aynsley.

O'NEILL: So, what are some standouts, or possibly some of your favorite examples of the queerness of gender and sexuality in nature.

SANDILANDS: There are many, many examples. Some of the ones that are held out as the most significant are examples that can be found in our relatively close primate relatives. One quite famous example are bonobos, who, let's say have very rich sexual and social lives that do not necessarily have anything to do with procreation and the creation of the next generation. Some of the examples that I like the best, however, come from my focus on the plant kingdom. And at one level plants are sexually very different kinds of beings than homosapiens. The idea that a plant possesses a sex or gender is actually a bit of an alien concept. However, one of my favorite examples of a delightfully queer plant is mulberry trees. Mulberries are, at least white mulberries, Morus alba, are normally dioecious, which means that there are pollen producing, quote, male trees and also pollen receiving, quote, female trees, the female ones being the ones that --- having received the pollen --- produce berries. But it gets a little bit more complicated because some mulberries in certain conditions are monoecious, meaning that they both produce and receive pollen. So they're both male and female. Mulberries also change sex quite frequently. The mulberry orchardist, to their immense frustration will you know, sort of one year discover that a certain proportion of their trees have decided to become male, thereby not producing fruit. And the reverse can also be true. But one of my favorite mulberry stories is that because they're a very fast growing quite beautiful, I think, and pollution-resistant tree, they are highly favored as street trees. And the trees that are favored as street trees tend to be the male trees because they don't produce large amounts of purple splats on the sidewalk. And precisely those male clonally reproduced trees are becoming a real problem, because they are producing prolific amounts of pollen. So they're actually also one of the most allergenic trees in the world. You cannot legally plant mulberry trees in some cities in the United States for this very reason. So, I like this story, because it demonstrates that this attempt to use sex as a way of controlling the trees' behavior completely backfired. And the trees kind of got their revenge. So, I'm fascinated with mulberry trees, because I am sort of fascinated by the complexity and diversity of sexual expressions in the more than human world. But I also think that thinking about sexual diversity and in fact, sex change as a relatively banal fact, of the multispecies universe, it's actually really important to emphasize that.

The concept of ‘queer ecology’ intersects with the fight for queer liberation and the fight for climate justice. (Photo: Alisdare Hickson, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

O'NEILL: What impact does looking at nature through this queer lens have on us as humans, not just the LGBTQIA+ community but the whole world?

SANDILANDS: I think that understanding nature as far queer, far more ritually sexually complicated, far more corporeally complicated and gender complicated. Thinking about the world in those terms, and not through the narrow lens of reproductive heteronormativity is, first of all, it's a very humbling experience to imagine that you know, what we as humans happen to do, or think or understand about ourselves as sexual beings is a tiny, tiny, tiny piece in a marvelously complicated universe. But politically, it also really challenges the idea that reproductive heterosexuality is the one natural way of doing reproduction and doing sex, and at a variety of different political moments, but I would say particularly at this political moment, that's pretty powerful evidence against the argument that queer and trans embodiments, queer and trans behaviors are somehow unnatural. And we see that rhetoric of unnaturalness occurring in, for example, the criminalization of homosexuality in Uganda, and also in arguments against providing gender affirming care for youth in Florida. The idea is that somehow that homosexual activity, homosexual attraction is unnatural, and the idea that trans embodiment is somehow against nature, that we're interfering with sort of the natural course of adolescent development by providing gender affirming care. The idea of queer nature really calls those rhetorics into question.

O’NEILL: How can we use queer ecology as a tool to help us fight the climate crisis?

There are many LGBTQIA+, and especially queer, trans and BIPOC networks of farmers who have found ways to creatively use the land and provide mutual aid for one another through practices like organic farming. (Photo: Markus Winkler, Unsplash)

SANDILANDS: I think queer ecology is one of a number of nodes of creative resistance to the economic, social, political, ecological relationships that are creating the climate crisis. I don't think that queer ecology is the only way to go. But I think that drawing on LGBTQIA+ histories of resistance and thinking seriously about the ways in which our intimate relationships can be other than tied to petrocapitalism, I think that's why queer ecology is actually pretty important at this moment. And that in current conditions, we see a flourishing of queer forms of land and property ownership. There's a number of queer networks and also more specifically QTBIPOC, queer trans BIPOC, networks of farmers who are grappling with these multiple forms of relationship and multiple forms of creatively providing mutual aid in times of economic crisis and that mutual aid extending to include better relationships with our more than human kin, either through organic agriculture, for example, or forms of thoughtful ecological restoration.

O’NEILL: Cate Sandilands is a writer, scholar and professor in the Faculty of Environment and Urban Change at York University. Cate, thank you so much for taking the time with me today.

SANDILANDS: It was my pleasure. Thank you, Aynsley.

Related links:

- Learn more about Cate Sandilands and explore her extensive body of work.

- Read more about the many examples of queerness in gender and sexuality in nature.

- Explore the Institute of Queer Ecology to learn about the intersection between queer ecology and art.

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

BirdNote®: The Power Of Albatross Partnerships

A Waved Albatross pair (Photo: Wildlife Travel, CC)

DOERING: The queerness in nature extends to birds, too. Wenfei Tong has this BirdNote about how sexual fluidity helps some seabirds raise the next generation.

BirdNote®

The Power of Albatross Partnerships

For most albatross species, raising a chick is a real challenge. Waved Albatrosses produce such slow-growing, needy offspring that females lay only a single egg every two years. And both parents need to share the load until youngsters can hunt on their own.

[Waved Albatross https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/203698321#_ga=2.41689515.888524604.16… 0:16-:19]

Albatrosses tend to pair for life, and it can take a while to find the right partner — so some species don’t start breeding until they are 10 years old, with some individuals even waiting until they are 20. Reunited pairs go through an elaborate, synchronized ritual of braying, wing spreading, and bill tapping to reaffirm their bonds before getting down to the business of breeding.

[Wandering Albatross https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/116338191#_ga=2.265744463.1576298121… 3:14-3:18]

In Hawaii, biologists were puzzled to find that some Laysan Albatross pairs had not one, but two eggs. Then they found that some of the birds going so faithfully through the ritualized series of courtship displays were both female.

Albatrosses tend to mate for life and can live more than 50 years. (Photo: Sidney Bragg, CC)

[Laysan Albatrosses https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/959#_ga=2.267683079.888524604.1609180… :24-:31]

Although the eggs were fertilized by males that had since died or were from other pairs, the females were bonded to each other. Many of these female couples remain together for years. They can’t successfully raise both offspring, but their combined efforts are necessary to raise one chick.

[Juvenile Laysan Albatross https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/32669#_ga=2.101412488.888524604.16091… :06-:12]

###

Written by Wenfei Tong

Senior Producer: John Kessler

Production Manager: Allison Wilson

Producer: Mark Bramhill

Associate Producer: Ellen Blackstone

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Waved Albatross ML203698321 S. Olmstead, Laysan Albatross ML959 E. Booth, Laysan Juvenile ML 32669 C. Robbins

BirdNote’s theme was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

© 2021 BirdNote March 2021 Narrator: Wenfei Tong

ID# albatross-03-2021-03-26 albatross-03

https://www.birdnote.org/listen/shows/power-albatross-partnerships

DOERING: For pictures, soar on over to the Living on Earth website, loe.org.

Related links:

- Find this story and many more on the BirdNote® website

- Learn more about the Waved Albatross

- Learn more about the Laysan Albatross

[MUSIC: Philip Boulding, “Margaret’s Arrival” on Musings: Celtic Harp Originals, by Philip Boulding, Magic Hill Music]

Beyond the Headlines

During the pandemic, the FDA relaxed its standards for the production of hand sanitizers, resulting in the use of some dangerous ingredients like benzene. (Photo: Trinity Care Foundation, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

O'NEILL: It's time now for a look beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. He's Living on Earth's contributor, and he joins us from Atlanta, Georgia. Hey there, Peter, what do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Aynsley, we've got a few eclectic items. There was a story in Wired magazine about how hand sanitizer had an industry wide boom thanks to the pandemic. The FDA relaxed its rules on how one could make hand sanitizer, and a lot of people got irresponsible to the point where one manufacturer out in the LA area had enough nasty things that killed germs and could potentially kill people, that it's hand sanitizer supply exploded and burned. And we're talking about chemicals like the known carcinogen, benzene, and many, many others. People who thought they were protecting themselves from COVID were actually exposing themselves to a whole new set of problems.

O'NEILL: Just a few weeks ago, I did a story where I talked with a scientist about hand sanitizers that contained quaternary ammonium compounds, which are now being linked to antimicrobial resistance. So that's another factor to take in. You gotta be judicious about your hand sanitizer use.

DYKSTRA: Well, I actually made my own three years ago. It's glycerin and alcohol, and a little bit of lemon juice for aroma. I think I'm pretty safe, but now you got me wondering whether I should throw it out.

O'NEILL: Peter, I feel like three year old lemon juice might be a good enough reason to toss it.

DYKSTRA: Oh, you have enlightened me once again, Aynsley.

O'NEILL: All right, and Peter, what else do you have for us this week?

Many typical outdoor summer activities, like summer camps, may be moving indoors due to extreme heat. (Photo: Smithsonian National Zoo, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Aynsley, I don't know if you went to camp in your summer vacations. I went once, my parents thought it would straighten me out. It actually, in their eyes, made me worse. So I never got to go to summer camp again. But I did spend a ton of time outside. There's a piece in The Atlantic that says that that is changing due to climate change, and warmer summers. The institution of summer vacation is making a change. And more and more of it is happening indoors. We're actually seeing some parks close because of the excessive heat this summer. Even worse, with the intense smoke from Canadian wildfires hitting some of the most heavily populated areas of the country and the American Northeast. And how much of summer memories are going to be impacted by a warming planet?

O'NEILL: One of the camps that I went to that was outdoors was marching band camp, and although I played clarinet, you can't have a kid marching around holding a tuba in that kind of uniform in this kind of weather. That's a recipe for disaster. So, looks like a lot of kids are going to have to start moving those camp stories indoors.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, but if you're going to stay outside, I've got another item that may be a little bit of good news. Dick's Sporting Goods became the second major sporting goods retailer after REI to ban PFAS, the forever chemicals that are of such a high health concern, in all of the Dick's Sporting Goods clothing, other textiles, tents, sleeping bags. And that will be something added to what Dick's calls its restricted substance list, including flame retardants, formaldehyde, phthalates, the plastic softener, and heavy metals as well. And when two industry giants like REI and Dick's make a decision, that tends to cascade down to all the other competitors.

Dick’s Sporting Goods is the second major outdoor apparel giant after REI to announce the removal of PFAS from many of its products. (Photo: Mike Mozart, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

O'NEILL: Well, Peter, do you have anything for us from the history books this week?

DYKSTRA: Of course, I've got some history for you, Aynsley. This goes back to 1906 when President Theodore Roosevelt decided that Owens Valley in California needed its lake and its river much less than the growing city of Los Angeles hundreds of miles away, needed it. What Teddy Roosevelt said was that the Owens Valley water is, "a hundred or a thousand-fold more important to the state and more valuable to the people as a whole, if used by the city, that being LA, than if used by the people of Owens Valley." That sealed the fate of the Owens Valley, dried up the lake, dried up the river, and turned them into prodigious producers of dust. It was also the first step in major water politics for LA and for so much of the southwestern US. And it also was a major irony, because we remember Teddy Roosevelt as the conservation president, and he absolutely killed off this productive farmland in order to grow a city in the southern part of the state. Now LA is huge, and Owens Valley is dust.

After over one hundred years of diverting its water to the metropolis of Los Angeles, Owens Valley is now a relatively dry landscape. (Photo: reverendlukewarm, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

O'NEILL: Alright, Peter, thank you for bringing us all these items. Peter Dykstra is a Living on Earth contributor, and we'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, Aynsley. Thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

O'NEILL: And there's more on the stories on the Living on Earth website. That's loe.org.

Related links:

- Wired | “The Explosive Legacy of the Pandemic Hand Sanitizer Boom”

- The Atlantic | “Summer Vacation is Moving Indoors”

- Environmental Health News | “Dick’s Sporting Goods Bans PFAS In Its Clothing and Other Textiles.”

- Archive.org | “Complete Report on Los Angeles aqueduct”

[MUSIC: Luizinho Vieira & Brazil Exess, “ Papai Oxala” on Musica Negra in the Americas, by Luizinho Vieira, Network Media]

Danger Days

Catherine Pierce’s poem “Danger Days” references a trope of 1980s movies commonly known as “kids on bikes” that harkens to a childlike innocence and freedom that she feels has been lost. (Photo: Berkan Küçükgül, Unsplash)

DOERING: By the way, there’s a name for those days of extreme heat and humidity that are changing summer vacation as the planet warms. Poet Laureate of Mississippi Catherine Pierce made it the focus of her latest work and its central poem.

PIERCE: The title of the book and the title of the poem is Danger Days, and that’s a weather term, and the definition of it is the epigraph of this poem. It’s when the combination of heat and humidity makes it feel like 105 degrees or hotter.

Danger Days

when the combination of heat and humidity makes it feel like 105°F or hotter

In the movies from the eighties, children

wore red pants and wild hair.

They were always circling cul-de-sacs

on banana-seat bikes, always wandering

after dark into woods full of hoots

and clicks. What haunted me more

than the ghoul-girls or gloved slashers

were the missing parents—not dead, usually,

just elsewhere. When the séance began

innocently, when the doll’s eyes popped open,

the grown-ups were never around.

They were off smoking pot,

they were date-nighting, affair-having.

They were office-stuck, their kids set

with house keys and frozen Salisbury steaks.

Sometimes they were home but sleeping,

snug and unghosted. Wherever they were,

they weren’t watching. We don’t live

on a cul-de-sac, so my kids ride their bikes

in a long, slow loop up our driveway

and back. I’d like to send them

rocketing down our tree-named streets—

Oakwood, Elmridge—but the main road

is Shadow Pines, and I’ve seen enough

movies to know what that means. I think

Catherine Pierce is Mississippi’s poet laureate, as well as the author of four books of poems including Danger Days and The Tornado Is the World. (Photo: Megan Bean / Mississippi State University)

of those gone grown-ups a lot now.

When the latest mass shooting alert pings.

When ire is gilded again into policy.

Tonight the weatherman says

Three danger days in the next week,

the heat a mouth closed around our state.

Outside, the humidity moans.

Trees grow talons. My husband and I

are up late again, watching the news

while our children sleep. We’re here

in our house off Shadow Pines, here

in the first part of a century bent

toward flaming out. Dear children

of the eighties, across the dark

country, phones and laptops and TVs

flicker. We’re watching now,

room after room after room.

Dear children of the eighties, can you

tell us now what was in the woods?

Can you tell us if watching

stopped anything from happening?

DOERING: That’s poet Catherine Pierce, whose latest book is called “Danger Days.”

Related link:

Catherine Pierce’s poetry and more

[MUSIC: Stan Samole, “It’s Raining It’s Pouring” on Childish Dreams, Traditional American/public domain/arr.Stan Samole, Jazz Inspirations]

O’NEILL: Just ahead, a firsthand account of working in the Canadian oil sands. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Afro-Cuban All Stars, “Fiesta de la Rumba” on A Toda Cuba le Gusta, Traditional/arr.Juan de Marcos Gonzales, Nonesuch Records/World Circuit]

Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands

The cover of Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands. (Image: copyright Kate Beaton. Courtesy Drawn & Quarterly.)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

The Athabasca oil sands in Alberta, Canada have been called the world’s most destructive oil operation, and for good reason. Extracting the thick bitumen involves razing the boreal forest and then strip mining the oil-rich sands underneath. And often, natural gas is burned to heat steam to force the oil out. The process is exceedingly resource intensive and, as a result, it’s one of the most costly ways of producing oil. It all makes the use of tar sands oil a major source of greenhouse gas emissions. And in May, a study from the government of Canada found that those emissions may be at least 65 percent higher than those reported by industry, adding even more warming to the atmosphere. And the effects of climate change were tragically felt right in the epicenter of the Athabasca oil sands when a 2016 wildfire in Fort McMurray burned twenty-four hundred structures. Eighty thousand people had to flee their homes, and the fire caused nearly $9 billion Canadian dollars in damages.

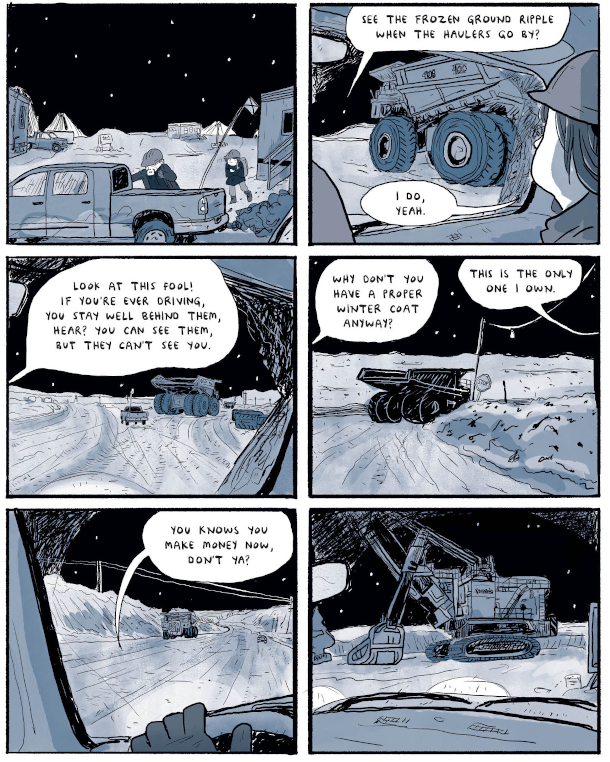

DOERING: And Aynsley, in addition to this environmental and climate toll, the extraction of these fossil fuels has also taken an emotional toll on some of the people who work in the industry. They typically live in austere work camps and rotate through 12-hour shifts both day and night, in temperatures frequently below zero degrees Fahrenheit. And for the women who have sought employment in the male-dominated oil sands, the job can bring unwanted comments and sexual violence. That’s a painful reality captured in the 2022 graphic memoir “Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands” by cartoonist Kate Beaton. Please be advised that we will discuss sexual assault in this segment. Kate Beaton joins me now from Cape Breton, Nova Scotia. Welcome to Living on Earth, Kate!

BEATON: Thank you.

DOERING: So can you tell our listeners the story behind the title and explain why you chose it?

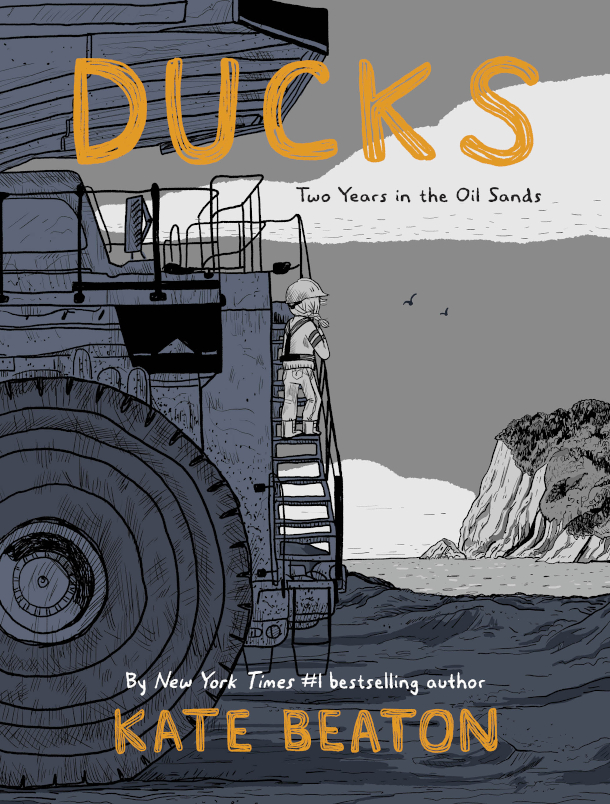

Ducks in flight. In 2008, around 1,600 ducks died after landing on a Syncrude tailings pond in Alberta. (Image: From Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands, copyright Kate Beaton. Courtesy Drawn & Quarterly.)

BEATON: Sure. The book is called Ducks. And there are a number of different things that you can take from that title. The main thing is that there was an incident in 2008, when I worked in the oil sands, when hundreds of ducks flew into a tailings pond at Syncrude, which is one of the sites that I worked at, and they died. And this became international news. And it was one of the first times where people really took a hard look at what was going on in the oil sands and decided that they didn't like it. When we were working there it seemed to be farcical because it was not as though those were the first animals that you saw that were endangered or dead because of the oil sands operations. And when you're reading the book, it's not the first animals that you encounter who have been impacted by these things. Around that same time, local Indigenous people were catching fish, and saying that they were finding cancerous lesions on them. And people were scrambling to find ways to discount that, to disprove it, to say, "No, I don't think so. I don't think this is what you think it is." And people didn't seem to care about the fish in the same way that they did about the ducks. Because it was easy to see that the ducks were all dead. But it was harder to admit that an entire watershed was poisoned. And these Indigenous communities were also reporting themselves to have high rates of cancer, rare cancers, things like bile duct cancer in their communities, in Fort Chipewyan and Fort Mackay, much higher incidences of those in their communities than you find in other places. And they're saying amongst themselves and to other people, you know, it's clearly linked to the oil communities. And people are bending over backwards to say "No, probably not." [LAUGHS] When it, when clearly the link is there. And how would you feel if people around you were contracting these rare cancers, and the government was trying to deny it, and the corporations were not claiming responsibility, and then they went out and made a gigantic fuss about these ducks? And everybody cared so much about the ducks? You know, you would, you'd be like, disgusted.

DOERING: Why did you decide to go work in the oil sands?

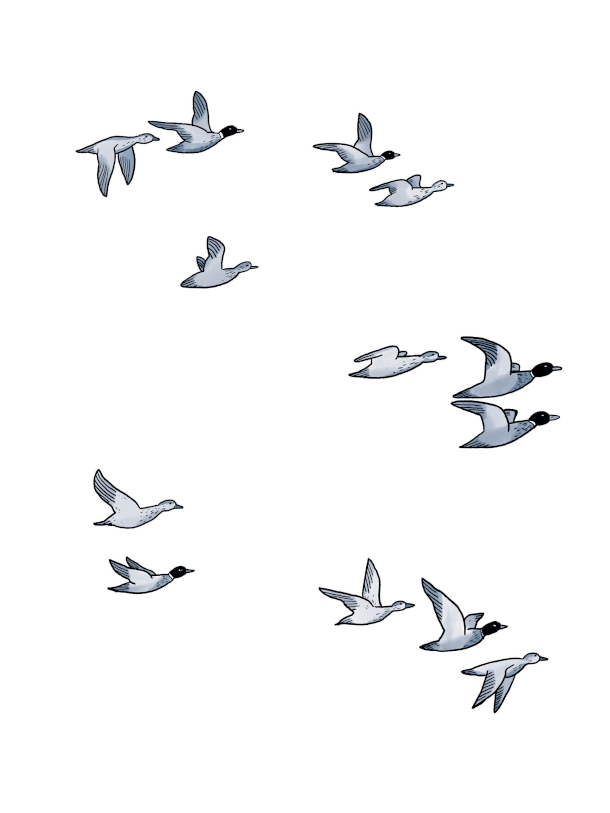

With $40,000 in student loans and no job prospects in her home of Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, Kate Beaton traveled West to work in the Alberta tar sands. (Image: From Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands, copyright Kate Beaton. Courtesy Drawn & Quarterly.)

BEATON: At that time, in 2005, that was the place where everybody was going to work. I had graduated from university, and I had this debt. It was only $40,000. But the truth is that I maxed out both the federal and provincial loans to get it. And it was more money than I could possibly fathom owing to anybody. And if I paid back only the minimum, I would end up paying it back so many times over in interest by the time I ended up paying it back. In Cape Breton, we had a pulp mill, we had Sydney steel, we had coal mining; all three of those were shut down by the end of the '90s. Those were major employers. And when you'd go to the guidance counselors in school, and you were like, "What do I do?" And they were like "Leave. There's nothing here." It felt like you had no options.

DOERING: There is this trauma of environmental health. And you describe some of the health issues that you had working at camp, and some of the perceived health risks. Can you tell our listeners about those and whether any of those have persisted?

Traveling to the Syncrude oil sands mine (Image: From Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands, copyright Kate Beaton. Courtesy Drawn & Quarterly.)

BEATON: Oh, yeah, there were lots. I mean, I think the first thing I drew in the book was when you would come home and you, I would always, like, cough up this weird gobs of things. I didn't know what they were; you'd just cough up this phlegm. And you'd be like, "Well, that was whatever I was breathing in all day. Don't know what that is." And I would get these rashes, especially on my back. They were from, like, what I assume is whatever was in the air rubbing between your skin and your clothes. Because we would come to work in the morning, when I worked in the office, like you'd be gone just like overnight, or maybe a couple of days. And you'd have to, like you could take your finger and wipe the film of dirt off the computer screen. So you knew that there was just stuff flying around in the air. Like that doesn't happen in your house. But it's flying around enough in the air there that it's settling on your desk in a short amount of time. So, you must be breathing it in all day. And everywhere you went, the signs were like, "Non potable," like, the water is non potable. So you had to drink from jugs of water that they had. It was like, it was an active mine.

Kate Beaton’s comic self-portrait. (Image by permission: © Kate Beaton)

The dangers were everywhere. We would have meetings every morning, safety meetings about how to not slip and fall and how that kind of thing so that if we hurt ourselves on site, the company couldn't get sued. But we never talked about things that would happen in the long run. Because anecdotally, you hear about people getting cancer who worked for a long time at Syncrude or Suncor, but no one's going to trace that back to the company. And no one is going to do a study on people who were working in the camps. If they worked there for a decade, and they got cancer two years later, no one's going to link that back. And no one's going to do that study, because who's going to fund it? The Alberta government? Yeah, right. My sister got cancer. Several years after working on site, and she, she worked there for longer than I did, several years longer than I did. And she had cervical cancer. And that's not related to breathing in things, and. But it spread so fast through her body that you will always wonder.

DOERING: I'm so sorry about your sister -- Becky, I think?

BEATON: That's right.

DOERING: Yeah, she's a pretty important character in the book.

BEATON: Yeah. And we joked about getting cancer in the book. I wrote that line in there before we even knew she had it.

DOERING: During your two years working in the oil sands, you experienced sexual harassment and assault, which you depict in your book Ducks with the lead up, and then just jet black pages completely filled with ink. How did the experience affect you emotionally?

The Syncrude oil sands mining complex at night. (Image: From Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands, copyright Kate Beaton. Courtesy Drawn & Quarterly.)

BEATON: Well, there was the harassment on the job, in the heavily masculine environment. It was nothing like I had ever experienced before, and I was completely unprepared for it. And even if you think that, it's going to be bad, it's nothing like what it is in person, the relentlessness of it. Because you don't just work there, you live there. You live in the work camp; you get up in the morning, and you go to work, and then you go home at night, and you sleep next to everybody. You shower with them in the morning, you eat your meals next to them, and there is no escape from it. There are people who don't know that they make you feel unsafe. There are people who don't care that they're bothering you. There are people who think that they have a connection with you because they are lonely. And they don't know that you are desperate to get away from them. It's not like regular society at all. And it becomes so much your new reality that you become inured to how much danger you're in, you stop pushing back. And when I did complain to my boss, when I was in a situation that was unsafe, he told me that he had no room for people looking for special treatment, and I felt ashamed. It was a signal to never complain again. And you don't want to be anything but a good worker, you want to be seen as a good worker, you are there to do the same job as everyone else. And you want them to respect you. When an episode of, of actual sexual violence happens, in retrospect, it wasn't surprising, although I never saw it coming. And in fact, it happened twice in a row very quickly. I had stopped seeing the danger around me because it was everywhere. And I was like a shell of myself. So of course, this was traumatic. And I carry that with me to this day. But I do not think that the men who raped me consider their acts to be rape. We came out of that place with different memories of what happened.

DOERING: What kind of support did you feel that you had, or didn't have, you know, from official channels and also in your personal life when this happened?

A panel from Ducks expressing the dangers of the heavy hauler trucks in the Athabasca oil sands. (Image: From Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands, copyright Kate Beaton. Courtesy Drawn & Quarterly.)

BEATON: [LAUGHS] There was no support from official channels. It was a place that prided itself on being a happy place for women to work. If you went to the website, you saw smiling women in hard hats and smiling people of color. It paid a lot of lip service to the idea that there was a zero-tolerance policy for things like harassment, which was just complete nonsense. But I did have support from my friends who were there. My sister was there, and my friend from university who joined me. And there were other female workers there, who you knew were going through the same things as you, and you could talk to them. I was lucky to have people who were close to me that I could talk to eventually. But it's not like it happens immediately, when something traumatic happens to you. You don't start processing it immediately. And that happens, I show it in the book -- it takes a while to talk about it and to understand my own feelings about it.

DOERING: Can you help me understand the way that you intersperse this image of bare feet on a shoreline throughout the book repeatedly? I think it returns again and again amid traumatic events. And it feels like it's kind of an escape or a balm for you, but I wanted to hear you talk about it yourself.

BEATON: Sure. That's the West Mabou beach in Nova Scotia. That's the beach in my home village. It's a very beautiful place. It's always peaceful. It's funny, growing up here, you can be like, "I need to get out of here. This place sucks!" In almost any kind of like beautiful, like bucolic rural space, the kids can be like, "I wish I went to, I wish I could go to a mall." Then you grow up and you leave and you come back and you're like, it's beautiful here. I see why tourists like to come here. [LAUGHS] You like took something for granted your whole life. And then you miss it so much. So these reoccurring images in the book of the feet in the water on the shoreline. It's kind of like, knowing where you're from, and where you're safe, and where you belong.

Steam-assisted gravity drainage is an “in-situ” oil recovery method in the oil sands. It requires heating steam, usually by burning natural gas, to force oil out from underground. (Image: From Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands, copyright Kate Beaton. Courtesy Drawn & Quarterly.)

DOERING: You managed to portray glimpses of beauty and wildness amid this grim landscape of the oil sands. Can you share what the Northern Lights and the pictures by your coworker represented for you there?

BEATON: The Northern Lights were beautiful. I had never seen them before. It was a night that was freezing. And they, they put me in a, in a shutdown shift, which is one where people are working overtime to fix this broken machine thing. And so I was alone in a tool crib. And it only had this tiny heater to heat it and it was minus 50 Celsius. And I don't know what that is Fahrenheit, but it's very cold. And a bunch of the workers had left a bunch of dirty tools outside and the bitumen had frozen on and I had to use degreaser to clean them all, but it was, they were all frozen. So I had to clean them really hard to get it off because it was so cold, but they were all metal as well, so they were all frozen solid. And my hands were just like popsicles. And all I had was that tiny space heater. So, I was laying on the floor next to it a lot of night as well. And I remember crying on the floor too, because I-- I never felt so alone. And then I walked outside to get another bucket of those tools. And I, I looked up, and the Northern Lights were above. And they were beautiful. And I took my helmet off. And I just I stood there staring at them for as long as the cold let me, because it was so beautiful. Before I left, there was a man, I called him Norman in the book. His name was Conrad Tabak. He had taken up photography as a hobby. He was like, "Everybody's got to have something to do here that makes them happy." He was a lovely man, an older, older man. And he went out when the Northern Lights were out, and he would go and take photos. And he was making blown up copies for people. He gave me one before I left, I still have it. It's downstairs. He was always looking for these beautiful things to take pictures of. But he died of cancer this year, just before the book came out. And I was so sad to hear that, because he was such a nice person. There were lots of nice people there. There were lots of nice people who looked for the beauty in things. It wasn't all terrible people. There were nice ones.

Cartoonist Kate Beaton (Photo: Morgan Murray)

DOERING: You now live back in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia. And I'm wondering what are things like there now, economically, socially, what does it feel like to be back?

BEATON: Well, it's different than when I left. It's not as bleak. Coal mining is gone; well, actually, they keep trying to bring coal mining back, but it's gone. Steel is gone. The pulp mill is back. But it's not the same as it was. The Internet has changed a lot, you know. We didn't have the internet when I left, really. But now, you know, people can work from home and they can start new businesses here. It really changes how a rural economy can operate when you have online options. And so someone like me can, I can work from here, whereas before I would have to live in a city or something like that, but I can, I can live here. There are more and more young people moving back, and people are hopeful about it. It's nice. And I'm glad to be part of that.

DOERING: Kate Beaton is the cartoonist author of "Ducks: Two years in the Oil Sands" and creator of the comic strip "Hark! A Vagrant." Thank you so much, Kate.

BEATON: Thank you, thanks for having me.

Related links:

- Find the book Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands here (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

- Kate Beaton’s Hark! A Vagrant comic archive.

[MUSIC: Cyrus Chestnut, “Over My Head” on Blessed Quietness: A Collection of Hymns, Spirituals, and Carols, anonymous 19th century African-American spiritual, Atlantic Records]

O’NEILL: Next time on the show, problems and pollution plague a Shell petrochemical complex in Pennsylvania.

FRAZIER: In one month, they essentially hit their 12-month quota even before the plant had started, and they've exceeded similar limits for carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, in subsequent months. And they've had other, you know, problems with air pollution, there was a release that caused benzene and volatile organic compounds to spike a couple months ago. Workers reported headaches and irritation in their eyes, according to the company. So, there've just been a lot of problems.

O’NEILL: And while the state has levied fines, they don’t carry much weight.

FRAZIER: Shell reported a nine-billion-dollar profit in the first quarter of 2023. And if you do the math, that's 100 million dollars a day. So, compare that to a ten-million-dollar fine. That's just not that much money compared to the size of the company.

O’NEILL: Tune in to Living on Earth next week to hear that story and more.

[MUSIC: Cyrus Chestnut, “Over My Head” on Blessed Quietness: A Collection of Hymns, Spirituals, and Carols, anonymous 19th century African-American spiritual, Atlantic Records]

DOERING: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Josh Croom, Swayam Gagneja, Madison Goldberg, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Sarah Mahaney, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Clare Shanahan, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari.

O’NEILL: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments at loe.org. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth