July 7, 2023

Air Date: July 7, 2023

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Montana Youth Climate Suit

/ Richard ForbesView the page for this story

A case in Montana brought by sixteen youth plaintiffs has become the first constitutional climate suit in the U.S. to make it to trial. They allege that the state of Montana has violated their constitutional right to a “clean and healthful environment” by promoting fossil fuel extraction in the face of intensifying climate disruption. Inside Climate News reporter Richard Forbes was in the courtroom and fills in Host Jenni Doering on what happened and how the young plaintiffs’ powerful testimony contrasted with a bare-bones defense from the state. (11:21)

Antarctic Deep Ocean Currents Slowing

View the page for this story

Climate disruption is showing up in the slowing of deep ocean currents that transport heat, carbon, and nutrients around the globe. Researchers found that deep ocean circulation around Antarctica has slowed by almost a third in the last 30 years, faster than predicted by climate models. Physical oceanographer Kathy Gunn joins Host Steve Curwood to explain what’s happening and why it may spell trouble for the entire climate system. (09:47)

A New War on Cancer – Part 1

View the page for this story

Treatments for cancer are better than ever, but cases continue to rise and cancer is still the second leading cause of death in the US. And with environmental factors linked to as many as two thirds of all cancer cases, some are calling for stronger chemical regulations as a means of cancer prevention. Kristina Marusic is the author of the book “A New War on Cancer: The Unlikely Heroes Revolutionizing Prevention” and joins Host Steve Curwood in Part 1 of their conversation to talk about why prevention is often overlooked. (09:47)

A New War on Cancer – Part 2

View the page for this story

Kristina Marusic and Host Steve Curwood continue their conversation about preventing cancer by reducing exposure to carcinogenic chemicals. Kristina Marusic shares the inspiring stories of cancer prevention advocates and discusses how lifestyle choices are overemphasized as cancer culprits, while chemical and pollution risk factors that people have no individual control over are too often overlooked. (14:33)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

230707 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Richard Forbes, Kathy Gunn, Kristina Marusic

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

Young people in Montana get their day in court to press their state to act on climate.

FORBES: It’s tempered hope, I think, what the plaintiffs are describing. Because they’re not ignorant of the fact that this one court decision is not going to fix climate change. But they’re unwilling to live without hope, and so they’ve decided that they’re going to believe.

CURWOOD: Also, a call to fight the cancer epidemic by cleaning up the environment.

MARUSIC: It's estimated that only 7-9% of global cancer funding goes toward prevention and the rest goes toward treatment and cures, and one of the big reasons for that is money. But any cancer survivor would tell you that they would have much rather had prevention, and I wanted that message to be central throughout the book.

CURWOOD: We’ll have that and more this week on Living on Earth – stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Montana Youth Climate Suit

Youth plaintiffs Badge Busse, Mica Kantor, and Eva L. are cheered on by supporters as they arrive for their second day of trial. (Photo: Robin Loznak/Courtesy of Our Children’s Trust)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

In June, a case called Held v. Montana became the first constitutional climate lawsuit in the U.S. to make it to trial. 22-year-old Rikki Held and fifteen fellow young plaintiffs allege that their state’s actions to promote fossil fuel extraction in the face of intensifying climate disruption violate their right to a “clean and healthful environment,” which is codified in Montana’s constitution. Their state and the world are already feeling the effects of the climate emergency, from extreme weather to wildfire smoke and ever-warming temperatures. The global average temperature reached a new record high on July 4, at 62.92 degrees Fahrenheit, breaking the record set just the day before. Facing down a future of even more warming, the young plaintiffs are asking the state of Montana to enact a plan for a clean energy transition. Richard Forbes is an environmental journalist focusing on the intersection between climate change and mental health, and he’s been covering the trial for our media partner Inside Climate News. Richard joins us now from Missoula to discuss the case. Thanks for joining us!

FORBES: Thank you.

In Held v. Montana there were 16 plaintiffs who were between the ages of 2 and 18 years old when the lawsuit was filed in 2020. Pictured here are plaintiffs Lander Busse, Badge Busse, Taleah Hernandes and Mica Kantor. (Photo: Robin Loznak/Courtesy of Our Children’s Trust)

DOERING: So, Richard, you were actually in the courtroom every day of this trial. What was it like to be there and see this trial in action?

FORBES: It was really special to be there. I started covering this story about 16 months ago, and at that point there was no real guarantee they were going to make it to trial, it felt very far off. So just for that simple reason of having talked to these young people, three of them in particular for about a year or more, and then realizing that they've made it all the way to trial, and that this was the first youth-led climate trial in the United States, it was incredibly special. Beyond that, I think there was a pretty remarkable amount of energy in the room. I don't know if there was anyone who was supporting the state who was sitting in the audience. From everyone I talked to, it seemed as if the audience was made up of parents, and some supporters, and then also the expert witnesses. I think the plaintiffs' testimony was very powerful.

The state of Montana argued that its contributions to global greenhouse gas emissions are so small that the state could not have a meaningful impact on global climate or on the health and wellbeing of the plaintiffs, even with significant changes to Montana’s fossil fuel extraction and energy systems. (Photo: Tim Evanson, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

DOERING: So, the plaintiffs in this case are concerned about catastrophic climate change affecting the state of Montana. How has the state responded to those claims?

FORBES: In essence, what the state is saying is that they're being sued for a particular statute that's part of the Montana Environmental Policy Act and that is purely, according to the state, a procedural act. And what that means is that it doesn't have any teeth. So the state argues that they don't have the capacity to deny permits based on MEPA. And as a result, they can't do what the plaintiffs are asking for, and even if they could, they say that Montana's emissions are so small, when compared to the global total, that it wouldn't make a difference in Montana. That was the state's framing, that if everyone doesn't fix this right now, at the same time, no one should be required to try, and that it's not worth trying. The plaintiffs were saying the complete opposite, which is that anyone can do anything to try to help, no matter what it is, the act of simply trying to help is a powerful act.

Youth plaintiff Rikki Held testifies in court (Photo: Robin Loznak/Courtesy of Our Children’s Trust)

DOERING: So I understand each of the 16 young plaintiffs in this case got involved because of their personal experiences with climate change in Montana, which I would imagine made it a very powerful trial to witness. Was there a particular moment or story during the trial that stood out to you as especially impactful or moving?

FORBES: Yeah, there were a lot of them. 12 of the young people testified, one father testified for his daughters. So, there were 13 different folks representing the plaintiffs' perspectives. I think the moment for me that stood out most clearly was, I spent a lot of time with Rikki Held in the reporting of my piece, and she was the first plaintiff to testify on the stand and the second witness in the trial overall. And she was asked what it felt like to be trying to work on her family ranch in temperatures that are 110 degrees, while there's wildfire smoke, and it was very emotional to watch her as she tried to hold back tears because of how awful it is for her to be trying to do manual labor, fixing fences and managing the cattle on her family ranch in those types of temperatures, and she did end up breaking down while trying to describe what that feeling felt like. That's only one of the many different ways that plaintiffs described their harms. A lot of it focused on wildfire smoke, being trapped in their homes unable to go out. People who suffer from asthma having trouble breathing, feeling like their throats were being closed up, unable to exercise, unable to do things that bring them joy, like spend time on the rivers. The plaintiffs' testimony was hard to listen to, and at the same time, it's their lived experience, it's the lived experience of everyone who lives in Montana nowadays.

During the trial, Rikki Held and other plaintiffs in the case described the impact of living with frequent wildfires and wildfire smoke on their health and wellbeing. (Photo: US Fish and Wildlife Service, USFWS National Digital Library, Public Domain)

DOERING: You mentioned that Rikki Held, the lead plaintiff in this case, who the case is named after, is a young rancher in Montana. And that's a very traditional line of work in the state. I'm wondering, to what extent do you think that connects with people in the state who might not otherwise really care or pay attention to a case like this?

FORBES: In many ways, her background is what I think folks think of a Montanan. She grew up riding horses, herding cattle, out on the range on her family ranch, it's 7000 acres in southeastern Montana. And that's her story and she's extremely proud of it. It's a huge part of who she is, she loves living there. It was incredible to be able to go spend some time with her on that ranch, and I hope that her story resonates with people across Montana. One of the biggest things that I heard from Rikki and some of the other plaintiffs I spoke to is that they feel very strongly they're not fighting for any political background or for any political perspective. They're trying to protect their state, and they're trying to fight for Montanans, and they want to protect Montanans, no matter their background, no matter where they come from. I don't know how that would resonate with other folks, but I hope they hear what the kids are trying to say.

Rikki Held is a fifth-generation cattle rancher on a 7,000 acre ranch in Southeastern Montana, a traditional role in the state. She described how being a rancher exposes her to climate impacts like extreme heat and wildfire smoke. (Photo: Zug Zwang, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: So, Richard, to what extent were there any surprises in the courtroom?

FORBES: I think I had a particular perspective on this lawsuit that's somewhat unique in that I've been following it for more than a year. And so, a lot of my experience following this case has been trying to understand what arguments the defense was going to make, and trying to figure out how effective those would feel. And I think the thing that I was most surprised by when coming into the courtroom is that the state did not have the most compelling argument. The defense, and I think this was a legal strategy, they decided really not to wade into the climate change issues whatsoever. They had a scientist, Dr. Judith Curry, who had been brought in for a deposition, who was expected to question some of the numbers of the plaintiffs' experts and who was expected to call into question some of the representations about how climate change is affecting both the plaintiffs' health and the state of Montana. And the defense decided not to call her to the stand. So, what the state did do is they brought two different employees of the Department of Environmental Quality to be very specific about what the Department of Environmental Quality actually permits and what authority they actually have. And, to be clear, that's quite limited.

Plaintiffs in the case are hopeful that if they speak up and try to make a change, they can have a future they want in the state of Montana. Montana is a state known for its natural beauty, with sites like Glacier National Park renowned nationally. (Photo: Cameron Cress, Unsplash)

And then they brought an economist named Terry Anderson, who was asked to compare the numbers between Montana's greenhouse gas emissions and the global greenhouse gas emissions. And he represented certain numbers during his testimony to the state, which was about five to eight minutes at most, and it was intentionally small, that's what it felt like, because under cross examination, Terry Anderson was unable to say exactly where he'd gotten the numbers from. And he claimed, in particular, that there was 2022 information that was available from a particular government agency. And the plaintiffs then revealed that that data has not yet been published. So, it is a real mystery as to where he got his data specifically. And I think that characterizes how the entire experience of being in that courtroom felt, is that the plaintiffs showed up extremely prepared with a really beautiful presentation that was easy to follow, and they presented over five days a really compelling argument. The defense presented their case in one day.

DOERING: Richard, climate change is one of the most daunting challenges we face. How much hope are you hearing from the young people involved in this case?

FORBES: It's tempered hope, I think, what the plaintiffs are describing, because they're not ignorant of the fact that this one court decision is not going to fix climate change. At the same time, and this was put different ways by different plaintiffs, but, they're unwilling to live without hope. And so they've decided that they're going to believe that changes can be made, that they could have a future that they want, they could have a future that is healthy and that isn't characterized by wildfires, and by extreme drought, and by the rivers drying up. They are aware that that's a possible future, and they've decided that they're going to feel hope. And every single one of them when they finished their testimony was asked by the plaintiffs' attorneys, "What would it mean to you if you succeeded in this case?" and they each said in different ways, I would feel hope. Not that everything can be fixed, necessarily, but what they were saying is, I feel hope that my state is listening to me, that people are listening to me, that changes can be made.

Youth plaintiffs walking and chatting outside the courthouse (Photo: Robin Loznak/Courtesy of Our Children’s Trust)

DOERING: So whether or not the youth plaintiffs actually win this case, to what extent do you think they've won in a way, just by speaking up?

FORBES: When I got involved in this story, I saw two different options for how I was going to cover it. There was the option where I was going to cover it from a very legally-minded perspective, trying to dig in as deeply as I could to the exact legal specifications of how this would work, what exact laws were being argued over, what exact strategies the lawyers were taking. I chose not to do that, one, because while that's all fascinating to me, I think it kind of misses the point a lot of the time with what this case actually is about, which is so much more about how people feel about climate change and what they're doing in relationship to it. This lawsuit matters, but it matters only in the context, I think, of how it's making these young people feel powerful and strong, and how they're hoping to then give that gift to the people who listen to their stories. It's so easy for this case to be turned into, like, very nitty-gritty legal stuff that really misses the point to me.

DOERING: Richard Forbes is an environmental journalist who covers the intersection between mental health and climate change. Thank you so much, Richard.

FORBES: Thank you.

Related links:

- Inside Climate News | “Love of the Land and Community Inspired the Montana Youths Whose Climate Lawsuit Against the State Goes to Court this Week”

- Inside Climate News | “In a Montana Courtroom, Debate Over Whether States Can Make a Difference on Climate Change, and if They Have a Responsibility to Try”

- The Guardian “‘Green Amendments’: Advocates Push for Constitutional Guarantees in Face of Climate Crisis”

- Montana Free Press “Landmark Climate Trial Over. Youth Plaintiffs Describe it as ‘Just the Beginning’”

[MUSIC: Geoff Muldaur, “I Can’t See Your Face Anymore” on Beautiful Isle of Somewhere, by Walter Davis, Tradition & Modern Gambit’/Radio Bremen]

CURWOOD: Coming up, climate change is wreaking havoc on deep ocean currents. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: The Marshall Tucker Band, “Can’t You See” on The Marshall Tucker Band, MT Industries, Inc.]

Antarctic Deep Ocean Currents Slowing

Oceanographers used research vessels to measure the temperature and salinity of Antarctic waters and gather data about deep ocean currents. (Photo: courtesy of Steve Rintoul)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

The oceans are home to a system of deep currents that circulate heat, carbon, and nutrients around the globe. And the icy landmass at the southern end of our planet plays a vital role in driving that global cycle. But as the planet warms, deep ocean currents around Antarctica are changing, much sooner than climate models predicted. A recent study from Nature Climate Change found that deep ocean circulation there has slowed by almost a third in the last thirty years, decades ahead of projections. Here to tell us more is lead author Kathy Gunn, a physical oceanographer from CSIRO Environment, who joins us from Hobart, Tasmania, in Australia. Welcome to Living on Earth, Kathy!

GUNN: Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: I was, well, frankly astonished to see that your research shows that Antarctic ocean currents are slowing much faster than predicted. What's going on?

GUNN: Yeah, so we had a study where we used observations to look at the Antarctic currents over the past 30 years or so. And we found this slowing of the circulation of about 30%. And that's something that wasn't predicted to happen by climate models until about 2100. And more recently by a model, which had a more realistic change in the ocean circulation, and they don't see it happening until around 2050. So, observational study suggests that the impacts from climate change are running a little bit ahead of schedule.

CURWOOD: So, talk to me about why the Antarctic ocean currents are slowing down.

GUNN: Of course. So around Antarctica, there's this very salty, very cold water formed. Because it's very salty and cold, it's very dense, and it falls off the Antarctic continental shelves and into the deep ocean. By that falling, it creates these currents. And those currents go on to fill the rest of the ocean. And they lie at the bottom, and they take about 40% of the ocean volume. So, they're very cold, and you can't really get them any colder. So, they're fixed there, but you can change their salinity at the source. And what we've seen is a freshening, so that makes these waters less dense and less heavy, so they're less able to sink. And that is effectively what's creating the slowing of those deep ocean currents.

Between 1992 and 2017, deep ocean currents slowed by 30%, according to the recent study in Nature Climate Change. (Photo: courtesy of Steve Rintoul)

CURWOOD: How concerning is this? I mean, what could long-term consequences for this change, this slowing of the deep ocean currents in Antarctica, what could it look like?

GUNN: So on the long-term, the consequences of the slowing is that we will start to see a decline in the health of our oceans. These deep ocean currents take oxygen down to the bottom of the ocean, where there will be creatures there that need the oxygen to survive. And with the slowing of the currents, there's less oxygen going to the deep ocean. So those creatures will have to change their behaviors or adapt where they're foraging for food to be able to survive. In a similar way to, you don't want a aquarium to stagnate, over time with this continued slowing, we'll see the ocean begin to stagnate. And that's as the oxygen doesn't reach the bottom. And also, these deep currents, they can stir up nutrients that have fallen from shallower places down to the bottom. But with a slowing of that deep ocean current, we'll see less of that stirring and refreshing, so the ocean will begin to stagnate. But that will play out over centuries or so.

CURWOOD: Or maybe a little bit faster, now, as we see that these changes are coming a little faster than we thought.

GUNN: Yeah, exactly. So, we might already be starting to see some of these changes, and we just don't really know exactly what's happening down there.

CURWOOD: What do you see as the relationship between these slowing Antarctic currents and climate disruption?

GUNN: The ocean as a whole plays a really important role, a critical role, in redistributing heat and carbon around the Earth. And these currents that we've been talking about are the deepest part of that ocean circulation. And if you start to get changes in one part of that circulation, because it's all connected, we would expect to see changes in the whole circulation system, which is what we call this overturning circulation, just really a north-south movement of water. So, we know that global surface warming is proportional to carbon change and carbon emissions. And that relationship is then partly determined by this ocean circulation. So, if we start to see changes in this ocean circulation, we expect that we'll see changes in how the carbon and heat is taken up in the ocean, and then redistributed around the globe.

Slowing ocean currents can exacerbate melting of the Antarctic ice sheets, causing further sea level rise. (Photo: Pedro Szekely Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Talk to me about where we might start noticing impacts of these slowing ocean currents, not just there in Antarctica, but also out into the global ocean.

GUNN: So, one impact that's been overlooked so far is how the change in this deep circulation will change sea-level rise. So, as you get the deep circulation slowing down, there's just less of that cold water at the bottom. And that gets replaced by warmer water that's overlying it. And that warmer water takes up more space, and it will increase sea-level. So, some of the impacts from that sea-level rise will start to happen over the next 10 or so years. And that sort of change is going to slowly creep further northwards with time. So places, low-lying islands, such as, say the Pacific Islands, places like New Zealand and Tasmania, would start to see some of those signals first, because they're closest to Antarctica.

CURWOOD: What impact do these changes in the deeper currents have on the Antarctic ice, do you think?

GUNN: Around Antarctica, as you get this melting in ice, you get more freshwater input. And that changes the structure of the water around Antarctica. With more freshwater, it changes the stratifications of the water. And that could then cause some feedback loops for the melting of the ice. But it's hard to say exactly how that will play out.

CURWOOD: I'm wondering if what I'm hearing you saying is that, as things get warmer, it's going to make things warmer?

GUNN: Yes, there's definitely going to be some positive feedbacks with these processes going on. But the reason that we don't exactly know how things are going to play out is because we might start to see some positive feedbacks in some areas, and then some negative feedbacks or opposite feedbacks in other areas. So this comes back to what we mentioned at the start of this, which is that it's very hard to model these processes, because there's so many interacting different components. And they all can be acting in slightly different ways.

CURWOOD: Let's take a look into the future. What condition might these deep ocean currents be in another 10 or 20 years, do you think?

GUNN: So over longer terms, I expect to see a continue of this slowdown. Now, there's definitely going to be some ups and downs on that with natural variability. And other things like sea ice, for example, the amount of sea ice can affect those deep ocean currents as well. But over the next 10 to 20 years, I expect that we'll continue to see a slowdown.

CURWOOD: You have your research protocol already set out for yourself.

GUNN: I guess so, yeah.

Kathy Gunn is a physical oceanographer at CSIRO Environment in Hobart, Australia. (Photo: courtesy of Kathy Gunn)

CURWOOD: So, how did you get all this data? How do you know what you're telling me?

GUNN: So, we used three different types of data. So, the first was observations from these repeat sections, cross sections of the ocean, where you collect measurements of temperature and salinity, essentially using buckets. But they're more sophisticated than that. And they're repeated every 10 years or so. And then we combine that with these instruments called moorings, which are moored to the seafloor in different locations. And they give us information about the temperature and salinity, as well as the speed. And so, we combine those two to come up with the estimates of the strength of this deep circulation. And then we filled in some gaps using some model output, which gave us information about the structure of how that flow looked like.

CURWOOD: How do you feel about this data now that you've gathered it and written up this impressive paper for nature.

GUNN: I feel that this provides more motivation to reduce emissions as quickly as possible. So that's the first thing, and the second thing is that it really motivates us to try and understand more about this very remote, very interesting region of the Earth. Because we expect to see these long-term signals, but we still don't know how that's going to play out with the shorter-term and more natural variability.

CURWOOD: Now, I'm speaking to you from the northern hemisphere, you're in the southern hemisphere. Us folks in the north tend to forget that the biggest part of the oceans are towards the south of this planet. And there's an awful lot of ocean there. To what extent is the data you've gathered a warning to the rest of us that live in the northern part of the planet?

GUNN: It's a warning in the sense that the whole ocean is connected and changes that we see in one part, which we might think is very remote to us, will actually impact the whole ocean.

CURWOOD: Kathy Gunn is a physical oceanographer and climate scientist based with CSIRO Environment in Hobart, Australia. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

GUNN: Thank you very much for having me.

Related links:

- The Conversation “Antarctic alarm bells: observations reveal deep ocean currents are slowing earlier than predicted”

- Nature Climate Change | Recent reduced abyssal overturning and ventilation in Australian Antarctic Basin

- Learn more about Kathy Gunn and her research

- The Guardian “Slowing ocean current caused by melting Antarctic ice could have drastic climate impact, study says”

[MUSIC: “The Greene Space at WNYC & WQXR” from “Arturo and Adam O’Farrill Live”]

A New War on Cancer – Part 1

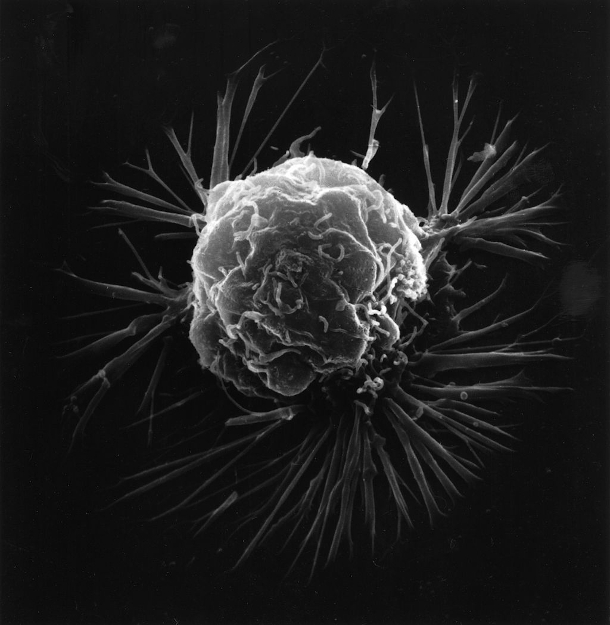

A breast cancer cell, photographed by a scanning electron microscope. Photo: National Cancer Institute, Wikimedia Commons)

DOERING: President Richard Nixon declared a war on cancer when he signed the National Cancer Act in 1971 and unleashed a wave of oncology training programs across the country. Now, more than 50 years later, treatments are better than ever, but cancer is still the second leading cause of death in the U.S., claiming the lives of one in five men and one in six women. And according to a 2008 study by a team at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Texas, more than two thirds of all cancer cases are linked to preventable environmental causes, including chemical exposure.

CURWOOD: Yes, and since the 1970s, more than 87,000 chemicals have been approved for commercial use in the U.S., but only around a thousand have been studied for their potential to cause cancer. And unlike the European Union, which takes a precautionary approach when it comes to approving chemicals, the United States generally does not examine the safety of chemicals before they’re put on the market for consumer use. But there are scientists and leaders across the U.S. advocating for stronger chemical regulation as a means of cancer prevention, as Kristina Marusic points out in her book, A New War On Cancer: The Unlikely Heroes Revolutionizing Prevention. Kristina is a journalist for Environmental Health News and joins us now from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Kristina, welcome back to Living on Earth!

MARUSIC: Hi, thanks so much for having me.

.jpg)

A New War on Cancer is Kristina Marusic’s first book. (Image: courtesy of Island Press)

CURWOOD: So, when President Biden came into office, he announced a war on cancer. How does that compare to the new war on cancer you're talking about here?

MARUSIC: Biden's war on cancer is a big influx of funding for, mainly, cancer treatment and looking for cure for cancer, which is important and worth pursuing, but my book really focuses on cancer prevention. And the new federal Cancer Moonshot plan does talk about prevention in a more meaningful way than it has in the last 50 years, so that's an exciting new development, but I'm still hoping to see more of a focus on prevention than we have in the past.

CURWOOD: I get the impression from reading your book that we spent an awful lot more on treating and trying to cure cancer than dealing with prevention. I'm wondering, to what extent is that related to where the money is, that this big money to help cure older people, perhaps who have a lot of money, and there's not a lot of money to help prevent cancer in kids and other people who have so much risk.

MARUSIC: So right now, it's estimated that only 7-9% of global cancer funding goes toward prevention and the rest goes toward treatment and cures, and one of the big reasons for that is money. So, the global oncology market was valued at around $280 billion in 2021, and it's expected to reach more than $580 billion by 2030. Cancer cases are expected to rise by 47% from 2020 to 2040, and investors point to that as evidence of strong growth for that market and, unfortunately, no one stands to profit like that from cancer prevention. So, if we want to shift our focus to cancer prevention, that's going to have to come from places outside of the market, through things like regulations and laws.

McDonald’s, one of the fast-food companies found to use PFAS in their packaging, vowed to stop using PFAS chemicals entirely by 2025. PFAS chemicals have been linked to kidney and testicular cancers, with links to other cancers under investigation. (Photo: Famartin, Wikimedia Commons)

CURWOOD: I'm wrinkling my brow because that kind of thinking sounds like, say, people who make ambulances seeing the car crash rate go up as a sign for better business for them. If people crash cars more, then they'll be able to sell more ambulances that'll get used without thinking about the tragedy behind the crashes.

MARUSIC: Yeah, it's a little distasteful, isn't it, to think about people profiting off of cancer treatments, but unfortunately, that's where the money is. And if we think about this, you know, if this was an actual war, this would be like spending 91% of our budget on treating soldiers who came back from the battlefield wounded, and only 9% of our funding on offensive or defensive measures that could stop them from getting hurt in the first place. So, it's not a great strategy, which is why my book is advocating for a bigger focus on prevention, specifically, preventing our exposure to cancer-causing chemicals in our everyday lives.

According to the American Cancer Society, about 9,910 children in the United States under the age of 15 will be diagnosed with cancer in 2023. (Photo: Tamaki Sono)

CURWOOD: One of the surprising pieces of information in your book is about the rising rates of childhood cancer. Since the 1970s, you say they've increased substantially, and it's now the leading cause of death by disease for children in this country. Why is that? Why are children so vulnerable to cancer now?

MARUSIC: Kids are vulnerable to all sorts of environmental exposures, more so than adults, because their systems that can help filter toxic chemicals out of their bodies are still developing, right? They're not fully there yet to be able to kind of process through harmful things that enter their bodies in the same way than an adult body can. They're also undergoing really complex development that adults have already been through and for all of that development to happen correctly, a long sequence of events needs to happen in just the right order, and at just the right time. And so, when there's a disruption to those processes, kids are more sensitive to those disruptions than adults are. There's also this growing body of research that suggests that parents’ exposures, both before and during pregnancy, can play a big part in not only childhood cancer risk, but also the risk that their kids will develop cancer as an adult, and there are a handful of more recent studies suggesting that those types of exposures might influence cancer risk for up to two or three generations. So, like, your grandmother's exposure to a cancer-causing chemical in the environment might influence your cancer risk, either in childhood or in adulthood.

CURWOOD: That's not good news, I have to say.

MARUSIC: It's not good news, no. It's a little alarming.

This ethane cracker plant owned by Shell is located outside of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. It uses ethane gas to make polyethylene, a process that releases cancer causing chemicals like benzene, toluene, hexane, formaldehyde and ammonia. After a lawsuit filed by environmental groups, Shell agreed to pay $10 million to Pennsylvania for violating state air quality regulations. (Photo: Nathan Smallwood)

CURWOOD: Kristina, why do you think it was important to include the stories of the scientists and doctors that are working on cancer prevention as you tell your story?

MARUSIC: So I mentioned that that funding problem we have with cancer prevention, that's one of the reasons we tend to not have resources devoted to prevention. The other reason for that is that it's a lot easier to advocate for cures and treatments than it is to advocate for prevention. So, when you're advocating for a cure or a treatment for cancer, you can put the face of a mom or a cute little kid on the poster or on the t-shirts, or on the Facebook page, someone who's battling cancer and it's really easy to get people to feel empathy and want to join the fight and help them out, because how could you not? And when we talk about prevention, it ends up being really data-heavy. So, there's a lot of statistics, and there's a lot of long-term trends in cancer rates, and it's just the nature of prevention that you don't get to know whose cancer you prevented. So, you don't get to meet the person whose life you saved, or get hugs from the family you spared from going through a cancer diagnosis and going through the process of getting treatment, and that's why I wanted to include these stories in my book. So, I profiled people who are advocating for cancer prevention, because I really wanted to humanize this story and try to put a face to cancer prevention. And I also found that as I was reporting on this topic as a journalist, the more I learned about these people who've devoted their lives to this work, the more I felt hopeful about our ability to do something to change this. And the more it made me feel inspired to want to get involved and help out, and so I hope it does that for readers, too.

Ami Zota is an environmental health scientist at Columbia University and directs the Agents of Change in Environmental Justice program. (Photo: Courtesy of Ami Zota)

CURWOOD: Now, throughout your book, you point to a few scientists or some leaders who are working hard to bring awareness to cancer-causing chemicals, and push for legislation or other steps to phase them out. Could you please walk us through the Ami Zota story?

MARUSIC: Sure. Ami Zota is a public health researcher and professor at Columbia University's School of Public Health. And her story is really interesting. So her background, long before she became a professor, she's a second-generation Indian American who grew up in rural North Carolina, and she told me that as a kid, she never imagined that she would be a scientist or a professor, in part because she'd never seen any women who looked like her in those kind of roles. Ami's life has been wildly different from the lives of previous generations of women in her family. Her mom grew up milking cows and water buffaloes in a rural part of India. And Ami's mom stopped going to school after fourth grade so she could stay home and help raise her seven siblings. And then, at a young age, she entered into an arranged marriage with Ami's dad, and Ami’s dad worked the night shift at their village gas station, but he wanted more than the opportunities their hometown could offer and he'd always been really good at school. So, he applied for scholarships, and he got one to go to medical school in a nearby city. And eventually, Ami's dad moved to the United States to finish up his medical residency at a hospital in Chicago, and he sent for Ami’s mom a year later. When she first moved to the States, Ami's mom didn't speak a word of English. She told me it was really difficult, tough for her mom to adjust, she was still really close with her family, and she was really homesick. And soon after, the family moved to rural North Carolina, where Ami grew up, and she shared with me how hard it was being the only Indian American that most of her classmates and her teachers had ever encountered. She shared one story about a friend coming over to play once when she was very young, and her grandparents were visiting from India. And the friend got so scared of Ami's grandparents that she started crying. She shared that one of her teachers consistently mispronounced her name as “Army.” And all of these experiences really helped shape the work that Ami does now as a researcher and as a professor.

Related links:

- Find the book “A New War on Cancer: The Unlikely Heroes Revolutionizing Prevention” here (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

- Learn more about Kristina Marusic

- National Library of Medicine “Environmental exposures and cancer: using the precautionary principle”

- National Cancer Institute “Cancer-Causing Substances in the Environment”

- Learn more about President Biden’s Cancer Moonshot Plan

- Learn more about Ami Zota

[MUSIC: Ravi and Anoushka Shankar, “Raaga Anandi Kalyan – Alaap” on Youtube, by Ravi Shankar]

CURWOOD: We’ll have much more with Kristina Marusic on the “new war on cancer” coming up right after the break. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Hugh Masekela, “Grazing in the Grass” on The Promise Of a Future, by Hugh Masekela, Chisa Music/BMI]

A New War on Cancer – Part 2

Clairton Coke Works is owned by US Steel and is the largest coke plant in the US, producing about 4.7 million tons of coke per year. In early 2023 US Steel was fined $307,000 by Allegheny County for air pollution violations. (Photo: Njaimeh Njie)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

We’re back now with our conversation with Kristina Marusic about her book, A New War on Cancer: The Unlikely Heroes Revolutionizing Prevention. Before the break, we heard the backstory of one of those heroes, Ami Zota, who teaches public health at Columbia University.

CURWOOD: So, Ami is noted for her work in cosmetics and other risks from endocrine disrupting chemicals. In fact, she's been on the Living on Earth broadcast. What do you think her experience as a woman of South Asian descent and a woman, what do you think her experiences along those lines helped her when she came to the field of public health and questions about these chemicals, which can be pretty dangerous to us, not just endocrine disruption, but of course cancer itself as well?

MARUSIC: Ami was one of the first researchers to frame those disproportionate exposures of toxic chemicals in beauty and personal care products among women of color as an environmental justice concern, and she helped develop a framework called the environmental injustice of beauty, but this framework links racism, sexism, and classism to negative environmental health outcomes. And one of the studies I wrote about in my book was a study she conducted in 2015, or she was a co-author for, and it was one of the first scientific studies to look at the connection between race and exposure to phthalates in feminine care products. Phthalates are endocrine-disrupting chemicals that interrupt our body's natural hormonal processes, and exposure to phthalates is linked to lots of negative health impacts, including things like obesity, reproductive harm, lowered IQ, and cancer. And Ami's study from 2015 found that using products like vaginal douches can contribute to phthalate exposure, and that higher rates of douching among Black women contributes to higher levels of exposure to certain phthalates than those seen in white women. But Ami's work is really revolutionary because she didn't just discover that link. She also insisted in her paper that we need to contextualize why practices like vaginal douching are more prevalent among Black women. And the context for that is that historically, white colonizers and enslavers used real or invented racial differences, like skin color, hair texture, and vaginal odor, as justifications for treating Black women as less than human. And so, striving to erase those real or invented differences became a survival adaptation. And the continued prevalence of vaginal douching among Black women is a lingering effect of that survival adaptation. So, Ami wrote, like, we can't address this problem of Black women being more exposed to these harmful chemicals without acknowledging the ways that systemic racism contributes to those realities. Another example is that women of color are more likely to use relaxers and straighteners to achieve straight hair, and hair relaxers and straighteners marketed to women of color contain more toxic and cancer-causing chemicals than hair products marketed to white women. And this also contributes to disproportionate exposure to cancer-causing chemicals among women of color.

Many personal care products and cosmetics contain phthalates which have been linked to breast and bone cancers, among other health problems. (Photo: pmv chamara on Unsplash)

CURWOOD: Your book is wonderfully written, and I encourage anyone who's more curious about this to look at it but we don't have enough time here to go through all of the people you call as unlikely heroes. But briefly, aside from Ami Zota, who else really impressed you in the process of writing this book?

MARUSIC: I also profiled an activist named Melanie Meade, who is a clean air advocate in Clairton, Pennsylvania, which is near where I live in Pittsburgh, it's in the same county about a 20-minute drive away. And Clairton regularly has some of the dirtiest, most polluted air in the country. Clairton is home to U.S. Steel's Clairton Coke Works, which is the biggest coke-making plant in the country. Coke is an ingredient used to make steel, and it's made by heating coal to extremely high temperatures, and the emissions are very, very carcinogenic. And it's also one of the oldest plants still doing that in the country, and the pollution controls have not been updated appropriately in a long time. And so, advocates there tend to refer to this as a pay-to-pollute system where it's cheaper for U.S. Steel to just pay the fines that they get for violating clean air laws on a regular basis, rather than overhauling their operations and putting in better pollution controls. And Melanie grew up there, has lived there most of her life, and over the span of about eight years, she lost every member of her immediate family to either cancer, respiratory disease, or heart disease. So that included both of her parents and her three siblings. And most people, I think, would have left at that point, but she has stuck around and is determined to fight for cleaner air on behalf of her community. I find her story and her resilience really moving. And it was really a privilege to get to know her and share her story in the book

Melanie Meade is a grassroots clean air advocate from Clairton, Pennsylvania, the location of the largest coke making plant in the United States. (Photo: Njaimeh Njie)

CURWOOD: And remind us of what you wrote when people said, "Well, why don't you just move"?

MARUSIC: Melanie told me, you know, that's where her community is. She's lost her immediate family, but that's really where her roots are. That's where both of her parents grew up, her family actually owned land and farmed that land in Clairton for generations, long before U.S. Steel ever came to Pittsburgh. So, she really feels like this is my community and it's worth staying and fighting for them. And I think part of the reason that's so inspiring is because I know there are Melanie Meades all over the country, who are in communities facing pollution and up against huge corporations and facing really impossible odds. And they stay and they fight instead of just moving somewhere else.

Berry Breene in her family's Oil City, Pennsylvania home. Berry was diagnosed with breast cancer at the beginning of the Covid 19 pandemic. (Photo: Kristina Marusic)

CURWOOD: Let's talk about PFAS for a moment. The so-called “forever chemicals” that are used in a wide range of products, including plastics and clothing and cosmetics and, and such. Now, in March, the EPA announced its first-ever national drinking water standards for six of these forever chemicals. Actually, there're probably thousands of them, but it's taken years for the federal government to even take action on these issues. What are some of the researchers that have pushed for regulations around PFAS, and what kind of impact have they had?

MARUSIC: I spoke with one researcher whose work focuses on PFAS for the book, her name is Laurel Schaider, and she's a researcher at Silent Spring Institute, which is a breast cancer prevention research nonprofit. And her work was among the first to find that PFAS are being applied to most of our to-go food wrappers, like the paper underneath of your pizza in the pizza box. And the little brown sheets of paper that your baked goods go in at the coffee shop. And even those brown biodegradable containers on your favorite salad bar often are coated with PFAS on the inside. And then she did a follow-up study that found that those chemicals are also migrating from that packaging into our bodies. And that people who tend to eat a lot of takeout had higher levels of PFAS chemicals in their bodies than people who mostly cooked their food at home. So those new drinking water limits that you mentioned are really important, you did mention that there are thousands, every time I check, the number of PFAS seems to have gone up. I think in my book, I said upward of 9,000 and now they're saying upwards of 15,000 different chemicals that fall under this category. So, putting a limit on six in drinking water, a lot of activists and advocates and health advocates say that doesn't go far enough, but it's still a big deal to kind of get the ones that tend to get into our water most frequently. But certainly, you know, we're exposed to PFAS in many, many other places in addition to drinking water, and food is a really big source of that. So, I would say, you know, based on my conversations with Laurel Schaider, that we also really need to think about regulating PFAS in food and food packaging, if we want to meaningfully reduce our exposures to those chemicals.

Berry Breene singing with the band Her Ladyship. Berry is an artist and a musician and her public murals can be found across Western PA. (Photo: Kristina Marusic)

CURWOOD: Throughout your book, The New War on Cancer: The Unlikely Heroes Revolutionizing Prevention, you tell us the story of Berry and her struggle with cancer. She's a young artist, I guess she grew up not too far from where you are in Pennsylvania. What sort of cancer did she experience, and why did you tell Berry's story?

MARUSIC: Berry was diagnosed with breast cancer at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. She got her diagnosis in March 2020. So, she had a particularly difficult experience going through her cancer diagnosis and treatment because she was mostly alone, because the world was in quarantine. And I wanted to include Berry's story in the book because it felt important to include a portrayal of what we're trying to prevent. So, we've gotten very good at treating cancer, thanks to all of that funding that goes toward cancer treatment and prevention that we discussed. So, a lot more people survive cancer today than did in the past. But treatment is extremely difficult. It's painful and it's scary and it's traumatic, and cancer survivors can have lifelong health complications related to the disease or the treatment they get for it. And any cancer survivor, including Berry, would tell you that they would have much rather had prevention than a cure. And I wanted that message to be central throughout the book, which is why Berry's story is woven throughout the chapters about the other people I write about in the book. Berry also had an experience that's common to a lot of people who get a cancer diagnosis, which was wondering if the choices she had made throughout her life contributed to her disease. You mentioned that she's an artist, and she mostly paints large murals and so, she was thinking, is this because I haven't worn protective gear when I've been painting? Is this because of those cigarettes I smoked when I was in college? Is this because I haven't been working out, or eating my leafy greens? And one of the reasons I thought her story was so important to include is that when we talk about prevention, we almost exclusively talk about personal lifestyle choices like diet and exercise and not smoking. And as a result, a lot of people who get a cancer diagnosis immediately start blaming themselves, or they feel shame and concern about, you know, what choices they made that might have led to their diagnosis. Especially if, like Berry, Berry didn't have any breast cancer in her family and she wasn't genetically predisposed to the disease, but Berry did grew up in a town that was once filled with oil refineries, and she spent most of her adulthood living in a city with lots of air pollution. And there are factors that raise our cancer risk that are outside of our individual control, that require us to work together and address them at a systemic level. Things like air pollution, things like our exposure to cancer-causing chemicals in our cosmetics and our beauty products and our food and our water. Those are things we need to work together to find solutions for. And when we leave out those kinds of risk factors in our discussions about cancer prevention, and make it all about, you know, the individual person's consumer and dietary habits, we're just not seeing the full picture and we're missing a whole world of opportunities for cancer prevention.

Kristina Marusic covers environmental health and justice issues in Pittsburgh and Western Pennsylvania for Environmental Health News and she is the author of "A New War On Cancer: The Unlikely Heroes Revolutionizing Prevention". (Photo courtesy of Kristina Marusic)

CURWOOD: Part of your subtitle includes the words “revolutionizing prevention.” In this season of the independence of the United States and that Revolutionary War, what revolution are you calling for?

MARUSIC: I'm calling for a revolution in the way we think about and talk about cancer risk and cancer prevention. And I'm specifically calling for a revolution in the way we fund cancer research and cancer prevention, right? So, I'm saying we need an influx of funding to help advance meaningful cancer prevention, and we need to really engage systems-level thinking and collaborative systems-level work to find solutions that will lower cancer risk for all of us, instead of putting all the burden on the individual to, you know, be a perfect consumer and eat organic and filter their air. All those things are worth doing, I would never want to discourage anyone from taking steps that might protect their individual health. And I would never say that we should stop funding or advocating for cures or treatments for cancer. My sister had thyroid cancer and cures and treatments saved her life, so I'm incredibly grateful that those existed. I am saying that while we continue looking for a cure, and funding new treatments, we need to do a lot more to prevent cancer. And it's not just that we need to, but it's that we can, right? It's that there's this whole array of ways to prevent cancer that we are not currently tapping or taking advantage of, and we could be preventing a lot of cancer if we shifted the way we think about this and talk about this.

CURWOOD: Kristina Marusic's book is called A New War on Cancer: The Unlikely Heroes Revolutionizing Prevention. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today, Kristina.

MARUSIC: Thanks so much for having me, Steve. It's been great talking to you.

Related links:

- Find the book “A New War on Cancer: The Unlikely Heroes Revolutionizing Prevention” here (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

- Learn more about Kristina Marusic

- National Library of Medicine “Environmental exposures and cancer: using the precautionary principle”

- National Cancer Institute “Cancer-Causing Substances in the Environment”

- Living on Earth February 17, 2023: High Levels of PFAS in Wild Freshwater Fish

- Watch Kristina Marusic’s conversation with grassroots activist Melanie Meade

- Watch Kristina Marusic’s conversation with Ami Zota and Zaria Golombek

- Learn more about Laurel Schaider

- Learn more about Berry Breene

[MUSIC: Goldmund, “The Ballad of Barbara Allen” on All Will Prosper, Western Vinyl]

DOERING: Next time on the show, the chasing arrows symbol gives consumers unrealistic expectations that our yogurt tubs, takeout containers, and bubble wrap will be made anew.

ROMER: The symbols on the bottom of plastic bottles and containers are called resin ID codes. And they were created to identify the type of plastic resin that the containers are made of. But the symbol isn't really meant to convey whether something is recyclable, it's just meant to tell you the resin number. And it doesn't necessarily mean that it can be recycled in your community. And so that's why EPA has recently urged to have the chasing arrows symbol decoupled from the resin identification codes, and to really set a very high bar for when something can be marketed as recyclable.

DOERING: Preventing harm to human health and the environment by giving consumers truthful information about plastics. Tune in to Living on Earth next week to hear that and more.

[MUSIC: Goldmund, “The Ballad of Barbara Allen” on All Will Prosper, Western Vinyl]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Josh Croom, Swayam Gagneja, Madison Goldberg, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Sarah Mahaney, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Clare Shanahan, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari. We bid a fond farewell to Bobby Bascomb and thank her for her many years of covering the environment and climate change for Living on Earth from the Brazilian Amazon to Puerto Rico.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at loe.org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram @livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments@loe.org. I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth