September 8, 2023

Air Date: September 8, 2023

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Too Hot to Learn

View the page for this story

As extreme heat linked to climate disruption becomes more common during the school year, many U.S. schools lack adequate cooling and ventilation systems to keep kids safe and focused on learning. Dr. Joseph Allen, an Associate Professor and Director of the Healthy Buildings Program at the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, joins Host Paloma Beltran to explain how temperature and air quality affect learning outcomes for low-income kids and students of color the most. (13:08)

Maui's Toxic Landscape

View the page for this story

The wildfires that killed more than 100 people and displaced thousands on the Hawaiian island of Maui left in their wake a toxic mess of melted and charred metals, plastics and more. Andrew Whelton, a Professor of Civil Environmental and Ecological Engineering at Purdue University, recently returned from Maui to help assess the risks and joins Host Jenni Doering to explain how testing air, water, and soil can keep communities safe from contamination as they rebuild. (13:00)

BIRDNOTE®: Birds and Plants of Hawaii

/ Michael SteinView the page for this story

For millions of years the Hawaiian Islands have been forged with fiery lava, a destructive as well as life-bringing force. BirdNote®’s Michael Stein reports on how this rocky archipelago became so abundant in life. (01:55)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Living on Earth Contributor Peter Dykstra joins Host Paloma Beltran to note the concern about climate change from young conservatives and discuss the results of a study that found coronavirus circulating among deer in Ohio. In the history books, they look back 35 years to 1988, when the massive Yellowstone wildfires spared the historic Old Faithful Inn. (04:45)

Hydrogen Fueled Future

/ Bruce GellermanView the page for this story

If you combine hydrogen from carbon-free sources and oxygen in a fuel cell, you get water and electricity. Bruce Gellerman reports on how this chemical reaction is fueling visions of future, carbon free flights and changing voyages of fantasy into reality. (13:30)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

230908 Transcript

HOSTS: Paloma Beltran, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Joseph Allen, Andrew Whelton

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Bruce Gellerman, Michel Stein

[THEME]

DOERING: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

DOERING: I’m Jenni Doering

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

In a warming world U.S. schools are failing at keeping kids and teachers safe.

ALLEN: It’s not too much to ask for a building that isn’t 80 or 90 degrees where a student can learn. It’s not that much to ask to have a building that prevents outdoor pollution from penetrating inside. We know exactly what to do, the money is there, the threat is known, and yet we haven’t done it.

DOERING: Also, big hopes for powering the world with the tiniest element.

BELT: Because of advances in renewable energy, because of the advances in electrolysis technologies, it’s absolutely feasible to see within 10 years that we could have a massive piece of the energy infrastructure based on green hydrogen.

DOERING: Those stories and more, this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Too Hot to Learn

Extreme heat can affect us in subtle ways, impairing our cognitive abilities and reaction time. (Photo: Chris Yarzab, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston this is Living on Earth. I’m Jenni Doering.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

Kids are back in school in the U.S., which may feel like the ninth circle of hell for some of them, and not just because of the homework and tests. With extreme heat still baking the country, many schools aren’t prepared for the effects of the climate crisis, leaving students and teachers with no other choice than to work inside sweltering buildings. In 2020, the Government Accountability Office estimated that around 36,000 schools in the US needed to update or replace their heating, ventilation and air conditioning, or HVAC systems. Many of those schools don’t have AC at all. Here to tell us what that means for kids and teachers is Dr. Joseph Allen, an Associate Professor and Director of the Healthy Buildings Program at the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health. Dr. Allen, welcome back to Living on Earth!

ALLEN: It's great to be on again. Thanks for having me.

BELTRAN: So talk to me about what happens to humans when the temperature climbs, and how do these health effects play out in academic settings?

ALLEN: Well, I mean, I think there's been a lot written this summer, in particular, because of all the heat waves we've had, around the health effects associated with extreme heat, everything from heat exhaustion, heat stress. I think what we tend to focus less on are the more subtle impacts, and particularly around what happens to kids in school, or anybody in school for that matter, including teachers. So this is not the kind of heat exhaustion where someone is going to collapse, or needs to be rushed to the hospital, has to be cooled down rapidly. But this is just what heat is doing to us while we're inside, even in conditions that are tolerable, right, to the body, that we think are tolerable. We think we're compensating, but study after study shows that it's having an impact on our ability to concentrate and perform and think clearly.

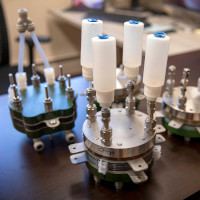

According to a study from Harvard University, students are 12% more likely to fail a test on a 90-degree day versus a 72-degree day. (Photo: US Department of Education, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BELTRAN: So what are some of those subtle effects? Can you tell me about a few of the studies here?

ALLEN: So in schools, there are studies that have measured indoor temperature and test scores, for example. And a really important one was one done in New York State, where they followed students for 10 years of test data. And it turns out that students were 12% more likely to fail a test if it was a 90 degree day versus a 72 degree day. And I think that's really interesting, one as a parent of three kids myself, but also as a public health researcher, and thinking about all the things we do for academic achievement, and it turns out temperature on the day of the test is going to have this impact on test scores. And this is something we see across every age group. We see similar results for workers, where we see worse performance on memory tests. We've done studies of university students showing that in higher temperatures during a heatwave, their reaction times on these cognitive tests decline. So it's really consistent in the sense that across every study, every age group, we see the impacts of heat in situations where people probably don't even know it's having that effect.

BELTRAN: Yeah, you know, how might short term learning outcomes affect long term education outcomes for the students, when we're talking about heat?

ALLEN: Well, you know, for example, SAT scores, well, if you're more likely to fail that test, and that's a standardized test that helps you get into college, well certainly then, the heat on the day of the test has influenced your long term prospects. I think another aspect of this when there's extreme heat, that's not just about your ability to concentrate, but also about whether or not you're in the school. And if you look at what has happened, as the climate changes, and the heat waves start earlier, and end later, we're starting to have conditions where schools are closed due to extreme heat. It's not just they're gonna perform worse when it's hot when they take a test. They're not even in the school.

BELTRAN: Wow.

Many school buildings in northern climates are designed to retain heat. This makes them particularly underprepared for heat waves exacerbated by climate change. (Photo: Jonathan E Shaw, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

ALLEN: I wrote about this in the Washington Post last year, where we had school closures in May, in places like Philadelphia, New York City, Washington, DC, Boston. I grew up in the northeast. We never had school closures due to heat, even in June. So you have like the direct impacts of extreme heat on learning and cognitive function. And then you have these, what's called indirect effects where the students are missing additional school days, because the building just can't handle the temperatures, right? The teachers, the students, the staff, can't be in the building. So this is interesting, too, because it becomes an equity issue. Because what do you do on an extreme heat day? You let some kids stay in schools, the schools that have air conditioning, and the kids in schools without air conditioning, you send home? That doesn't seem right. And not only is it not right, it should be totally unacceptable. So extreme heat's changing, or should be changing a lot of people's minds about how we think about the role of the school building and buildings in general, on well being.

BELTRAN: So there's different outcomes for different geographical areas here.

ALLEN: Yeah, that's really important, because in a lot of these conversations I've been having this summer with the heat waves, we need cooling in our buildings and our schools. And the reality is that a lot of the South already has this. A bigger issue, even though the temperatures don't get as high, is what's happening in places that are traditionally cold weather climates, like the northeast, like in the Pacific Northwest, in Seattle. Very few buildings have air conditioning, they haven't had a need for it. And in fact, the buildings, many buildings in these climates were designed to retain heat. Think about schools where I'm in Boston. They're designed to retain heat, because most of the time, we need to heat these schools, and we're protecting against the cold. And now you have these buildings that don't have the ability to cool, the building materials actually absorb and retain heat. And it's a recipe for a problem that we haven't had to face. And because of climate change, we're facing it, it's acute, and it's only going to get worse.

BELTRAN: Yeah, I mean, extreme heat, which as you mentioned right now, will only get more extreme as the climate crisis continues, that's a major challenge. But it's not the only one. How does extreme heat intersect with other environmental issues? I'm thinking, air pollution and wildfire smoke.

ALLEN: Yeah, this has been a source of frustration for me, because what I see out there a lot is that we're treating these crises in different silos. In June, on the east coast, we were, everyone's focused on wildfire smoke. In the middle of the summer, everyone's talking about extreme heat. Then we're talking about COVID. And the conversation starts to hit, you know, these cycles of panic and neglect. And the reality is that all of these crises run through our buildings, and they're related. So if you make improvements to the building systems that help with COVID, specifically improving ventilation and filtration, well, that's going to help against wildfire smoke, which is an outdoor pollution problem. But it becomes an indoor problem as that starts to seep into our buildings. Same thing with extreme heat. The problem runs through our buildings, the solutions run through our buildings, right? If you if you have a high performing building, then wildfire smoke is not a threat, then extreme heat is not a threat. And COVID, influenza, RSV, other respiratory pathogens, are a much lower threat.

BELTRAN: And what do we know about CO2 levels in classrooms? And how does it connect to ventilation?

Dr. Allen says school building designs should simultaneously address the threats of respiratory infections, outdoor air pollution, and extreme heat. (Photo: Chris Zuniga, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

ALLEN: So when you design a building, there are standards for how much outdoor air should come in, right? We've talked about ventilation, how much outdoor air is coming into the space. Based on the number of people in the space, the size of space, and those rates of air coming in, that will determine the CO2 level, the carbon dioxide level, because humans are the main source of carbon dioxide indoors. And so carbon dioxide levels are related to ventilation, but we regulate or set standards for ventilation rates. Couple problems. The current standards for schools are bare minimums, not designed for health. It's the standard for quote unquote, "acceptable" indoor air quality. Not good, not healthy, not optimal, just acceptable. A bare minimum. So we design our schools for these low ventilation rates that are well below what the science says we should be doing. And then they drop in performance over time if they're not maintained very well. So you can actually use carbon dioxide as an indicator of that ventilation rate. Now, that said, there are some efforts, including some underway in New York City, to set requirements for monitoring carbon dioxide, which is a great indicator for ventilation. To me, that would go a long way. Because it's the classic business maxim, you can't manage what you don't measure. We haven't been measuring indoor air quality. Boston Public Schools, where I am, deployed real time indoor air quality sensors with carbon dioxide monitoring in all their schools. Parents can look up the data about their kid's classroom, a teacher can look up about the classroom. And I think it should be standard in schools across the country to measure it, because then we can't hide from the problem. It's one thing, it's pretty, you can be pretty hand wavy about it and say, oh, yeah, we have indoor air quality and ventilation under control. It's another thing to have someone monitor in that space, and objectively determine, is this space performing as it should? How are you actually going to know if it's meeting the new CDC target, let's say, of 800 parts per million of carbon dioxide? The only way to know is to measure. So we should be measuring and monitoring. We also need to lift those baseline standards from these acceptable minimums up to true health based targets.

BELTRAN: To what extent is this issue disproportionately affecting students of color and low income students?

ALLEN: Well, like much of what we see in society, and much of what COVID revealed, the disparities are wide when it comes to school buildings and the indoor air and indoor environmental quality. Take, for example, ventilation rates. So we know that all schools are not designed to the appropriate health based targets. But we also know that schools where the majority of kids are Black or Hispanic, have even lower ventilation rates on average. And in schools where the higher proportion of students are on free or reduced lunch, so lower income communities, we also see even lower ventilation rates. So it's truly appalling, the state of our schools, the state of some of our schools, that we've let them slide so far that even these, these well known hazards are not addressed. This is one of the big issues with this topic. We shouldn't even be having this conversation. It is totally unacceptable that we would have kids in a learning environment that was not safe, comfortable and healthy. It's not too much to ask for a building that isn't 80 or 90 degrees where a student can learn. It's not that much to ask to have a building that prevents outdoor pollution from penetrating inside. It's not that much to ask to have a school building with ventilation and filtration that protects against respiratory pathogens. We know exactly what to do, the money is there, the threat is known. And yet we haven't done it. We've neglected our buildings and our school buildings in particular, for decades upon decades. It should be totally unacceptable.

On average, schools with higher proportions of students of color and low-income students have lower ventilation rates. (Photo: Melinda Young Stuart, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BELTRAN: So you mentioned that the money is already there to make these changes. So what kind of federal funding is available for schools to implement some of these strategies?

ALLEN: Well, the best source of funds right now is still the remaining pandemic funds, which can still be spent on improving the school building. They're COVID related, but it goes well beyond that. The changes you make to ventilation and filtration address the extreme heat issue, address the air pollution issue. The funding can be used for things like indoor air quality monitoring. You can give your building a tune up, a process we call commissioning, which is a great step. It saves energy and also improves indoor air quality. It's like giving a tune up to a car. So there's actually a lot you can do. And the money that's sitting on the table is still out there and available through the pandemic relief funds.

BELTRAN: What can people do here, listeners that are concerned about air quality in their schools, ventilation? What can they do?

ALLEN: I think first thing people can do is just start talking about it a bit more, right? The way things get done is you start to socialize it, and then demand it, and you start asking questions. What have we done to improve ventilation? Are we meeting the new CDC targets for carbon dioxide indoors? So I think the first part is start asking it, I'd start to demand monitoring and disclosure. Because I think that's when real change can happen, because there's some data to point to. There's also some tools we built if people are, you know, on to that next phase. So you can go to the Harvard Healthy Buildings Program website, we built a tool that helps you set a carbon dioxide level for a classroom. A teacher can do this, a parent can do this, to say, you know, what, if we're measuring, what level is acceptable, and what's unacceptable? We built a little tool to help you think about a portable air cleaner in the space, how to size it right. So it's great for wildfire smoke, great for COVID, great for influenza, but I think most important, we just have to keep talking about it, make sure that the school building isn't an afterthought.

BELTRAN: Dr. Joseph Allen is an Associate Professor of Exposure Assessment Science at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. He's also the Director of the Harvard Healthy Buildings Program. Thank you so much for joining us.

ALLEN: Thanks for having me on. It's my pleasure.

Related links:

- Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health | “Healthy Buildings Program”

- US Government Accountability Office | “School Districts Frequently Identified Multiple Building Systems Needing Updates or Replacements”

- Harvard University | “Temperature, Test Scores, and Human Capital Production”

- Harvard University | “Education Under Extremes: Temperature, Absenteeism, and Disciplinary Infractions”

- American Economic Association | “Heat and Learning”

[MUSIC: Senor Happy, “Love If You’re Real” on I’m Sorry, by Derek Schanche, Division Records]

DOERING: As harvest season approaches, join the Living on Earth Book Club to hear how regenerative farming can combat climate change and food scarcity. “The Great Regeneration” author Dorn Cox will join us for this free event on September 14th. Tune in to our livestream at 6 p.m. Eastern or join us in person at the Dover Public Library in New Hampshire. Just go to loe.org slash events to register and learn more.

[MUSIC: Senor Happy, “Love If You’re Real” on I’m Sorry, by Derek Schanche, Division Records]

BELTRAN: Coming up, the environmental hazards to manage as Maui communities clean up the destruction left by the deadly wildfires. Stay tuned!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Clifford Brown, “Yesterdays” on Artist’s Choice: Elvis Costello, by Clifford Brown, He/ar Music/Universal Music Special Markets]

Maui's Toxic Landscape

This is an area impacted by the Kula Fire visited by Professor Andrew Whelton. (Photo: Andrew Whelton)

BELTRAN: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Paloma Beltran

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

This summer has brought no shortage of climate trauma. Heatwaves across the world, supercharged hurricanes in the Atlantic and Pacific, and floods in India, China, and Turkey. Wildfires have scorched Canada, Greece and Hawaii, where blazes on the island of Maui killed more than 100 people and displaced thousands. And with neighborhoods in ruins, the danger is far from over. The homes and shops that burned in the fires are now a toxic mess of melted and charred metals, plastics, and more. Locals have been getting some help understanding the risks and how to safely go about cleaning up the debris from people including Andrew Whelton, a Professor of Civil Environmental and Ecological Engineering at Purdue University. He and his team helped assess contamination and water safety issues after the 2017 Tubbs Fire and the Camp Fire just a year later in California, and the 2021 Marshall fire in Colorado. Professor Whelton recently returned from the communities of Lahaina and Kula on Maui and joins me now. Welcome to Living on Earth, Andrew.

WHELTON: Thanks for having me.

DOERING: What kind of toxic waste usually results from fires like the one we saw in Lahaina, Maui. What hazardous materials are we talking about?

WHELTON: Well, several days after the fires were put out, US EPA and other agency officials went in to start removing and separating hazardous waste and hazardous materials from the property so that it can start to be cleaned. These types of things include paints, propane tanks, other chemical materials that may pose a health risk, and you can't necessarily pick them up and put them into a truck and send them to a landfill, you have to separate these things. There was also concerns about many of the homes that were destroyed, were made of asbestos, there was asbestos parts of it and so under living conditions, asbestos doesn't necessarily pose a hazard. But once the structures are destroyed, that asbestos can be released into the air and the environment and then pose an immediate health risk to everybody around them. Fires like we saw in Lahaina and Kula can exceed 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit, sometimes even burn hotter. And this sometimes can cause metals to deform in some cases melt. So you can have metals on cars kind of melt out and then cool right underneath the cars. Or, you can have tires burn, which are plastics and other plastics in buildings and infrastructure. When these materials burn, they create all sorts of new chemicals that were not necessarily present in the parent product. And those can be released into the air, they can release into the water, or they can form particles that deposit on the ground and nearby that can run off and pose inhalation or exposure risks.

Several properties had observed plumbing damage. Some were uninhabitable. In Kula, the community fought the fire itself with hoses and water tanks until the fire department arrived. There are some harrowing stories. (Photo: Andrew Whelton)

DOERING: And are these chemicals that it'd be very clear if they're smelling in the air or tasting in the water? Or are some of these, you know, harder to detect and not necessarily obvious to people in the area?

WHELTON: Many of the chemicals that are produced when you for example, burn plastics, can be immediately harmful. And some of them you can smell at levels before they cause harm. And others you cannot. For example, benzene, you can smell benzene in drinking water at 2,000 parts per billion. But it's immediately harmful at 200 parts per billion. So you wouldn't necessarily be able to smell it, which is why officials need to do extensive environmental and water testing of the area to find and then remove these threats from the communities that were impacted.

DOERING: And how do they decide what kinds of chemicals to test for? I mean, I know that in trying to ensure that PFAS chemicals are not contaminating water systems, we're not testing for all of the PFS chemicals that are out there. There's really just a handful that we test for. So how do people who are trying to keep the people in Maui safe decide which chemicals are most important to test for?

Lots of drinking water safety questions - and rightly so.

— Andrew Whelton ????????❄️???? (@TheWheltonGroup) August 20, 2023

Residents have seen water utility staff put sampling and have told them they appreciate them.

We’ve been taking samples too with @UHawaiiNews collaborators.

8/n pic.twitter.com/u7nsX4Af38

WHELTON: That's a great question. And generally what happens is right after a disaster testing isn't necessarily conducted. It's primarily triaging the contamination trying to stop it from moving off site. In Maui and near Lahaina, for example, Lahaina borders the ocean and so there's concerns that some of the contamination will be flushed into the ocean and then affect the coral reefs nearby. So a lot of the initial work is to protect the environment from the contamination moving off. During disaster debris removal, there are, for example, 21 different types of heavy metals that would be tested for including arsenic, cadmium, and some of the others that are used to determine whether or not the soil poses the health risks to people nearby, and whether or not additional cleanup has to happen. For drinking water. That's more nebulous and what I mean by that is, since 2017, we've been compiling a list of chemicals that show up in drinking water after wildfires but prior to 2017, there was no list and people really didn't test. So different aspects of this recovery, in how they go about testing differs based on just the level of knowledge that officials have in who they engage to help them.

DOERING: And then what about chemicals in the air? How does that testing work and what's really the big concern there?

WHELTON: One of the concerns in Maui is that the particles and dust, toxic dust from structures burning and such can be resuspended in windy days. And so while we were there, recently, there were 30 mile an hour winds and that can cause suspension of these particles in the air. Some of those not only carry with them contaminants like heavy metals, but they can be small enough that they can go deep into your lungs and impose another hazard. So one of the testing approaches that is typically used are look for particulate matter. These are particles to see you know what size, what amount of particles in the air. And then there's also other testing approaches where you try to capture and then quantify how many and what type of VOCs or volatile organic compounds are released from debris or just suspended in the air.

There were remarkable stories of residents. Many fought the fire before responders arrived. The fire moved so fast through the dry underbrush and trees. Some of the residents nearly died. Propane tanks exploded. (Photo: Andrew Whelton)

DOERING: And what if anything, can cleanup crews actually do about that dust? Is there anything they can do to prevent it from just flying around in the air?

WHELTON: Yes, what is happening in Maui is similar to what type of countermeasures were in place after the Marshall fire. So what the officials will do is they'll spray this type of polymer coating on top of the debris. And then that will prevent that debris from being suspended by air, it's kind of like a shield. And it also reduces the hazard of people walking around, say, the middle of the streets, so that they know that the debris won't find its way to where they are.

DOERING: So given all those hazards, what steps are required before communities in Maui actually begin to rebuild or move back in?

WHELTON: Well, the process right now is still in the response phase, where officials are trying to understand the scale of environmental contamination, at the same time as helping households and businesses relocate and try to stabilize their near term future. In the larger picture, it's going to be months before the debris is removed from these damaged properties. And that's primarily because of the contracting process, the government policies and procedures that have to go into selecting these contractors, we typically see debris remain on property sometimes for six months, before it's removed. And so that's why it's really important to stabilize this material, so that it doesn't run off into the waterways and the nearshore environment. So it's going to be a long process.

DOERING: You know, after a devastating fire like this sweeps through a community, there's often these pictures that we see after the event of people going back home and picking through what's left of their lives. You know, maybe finding a photograph here, a family heirloom there that somehow survived. But how is that able to happen? If there's all of this potentially hazardous stuff around in Lahaina? What does sort of picking through the remains of their lives look like there?

Some households in the Unsafe Water Alert area are relying on water buffalos for water.

— Andrew Whelton ????????❄️???? (@TheWheltonGroup) August 21, 2023

Some households don’t for various reasons we are finding.

10/n pic.twitter.com/HMKqHVHbzL

WHELTON: Well, there are some very skilled groups that will come in and help households and business owners sort through their properties. And one of them is Good Samaritan's Purse. They have the training and the safety equipment needed to go in and help people search through their property for special mementos and other things that they can recover. We actually encountered some of these professionals in Kula, and they were helping out a family who said that they just couldn't bring themselves back to go through their property. They were looking for specific things and they also had several young children who couldn't see their house because they couldn't process what was happening. For people that go and do their own searching of their property they need to wear very specific personal protective equipment, gloves, long sleeve shirts, close toed shoes, sometimes respirators, and sometimes Tyvek suits, because the materials that are there are now hazardous. And you need to protect yourself and your family from any exposures that could cause harm because we don't want this disaster to have long term health implications. And that's one way that we can help avoid that.

DOERING: Now, from what I understand you talked to elders in Lahaina about some recovery options. What did you take away from talking with them?

WHELTON: While we were in Maui, helping out the local community, University Hawaii and government agencies we did get invited to talk with the Hawaiian community. And that was an amazingly memorable experience. The Hawaiian community came together right after the fires and started helping each other, get through this disaster. The Hawaiian community was rescuing people from their cars and their homes. They were setting up convoys, to bring in bottled water and other food items to people through the beaches. And they truly have a connection with the environment and community that I have not seen anywhere else at any other disaster.

Andrew Whelton is Professor of Civil, Environmental, and Ecological Engineering at Lyles School of Civil Engineering, in Purdue University. (Photo: Courtesy of Andrew Whelton)

DOERING: Of course, a lot of the recovery effort depends on the help of government agencies, in addition to the hard work of the local community itself. What's been the communication like so far between agencies like FEMA and local communities?

WHELTON: Initially, the local communities were the ones who organized and started supporting each other. They were in many cases, the first responders, not just the firefighters.

DOERING: But everyday people basically got garden hoses and buckets and started trying to fight fires. And together, they were able to put out some spot fires.

WHELTON: FEMA and other agencies came in shortly after. And there has been some friction between these groups primarily because these agencies came in and started telling people what to do, not necessarily recognizing the trauma that the community had gone through, and the just heroic acts that the community members had done in absence of FEMA and these other agencies. And so, over the last several days, we've seen multiple meetings with these agencies and local community to try to iron out any of these remaining issues, so that the majority of energy can be focused on helping the people in a way that they need help.

DOERING: Andrew Whelton is a professor of Civil Environmental and Ecological Engineering at Purdue University. Thank you so much, Andrew.

WHELTON: Thanks for having me.

Related links:

- Andrew Whelton for The Conversation | "After Maui fires, human health risks linger in the air, water and even surviving buildings"

- PBS | “Amid Grief and Loss, Maui Residents and Businesses Continue Wildfire Recovery”

- Learn more about Professor Andrew Whelton

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

BIRDNOTE®: Birds and Plants of Hawaii

The I’iwi or scarlet honeycreeper primarily lives in moist forests between 4,000 and 6,000 feet on the islands of Maui and Hawaii (commonly known as “the Big Island”) and uses its long, curved bill to drink nectar. (Photo: USFWS Pacific Region, public domain)

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

BELTRAN: For millions of years the Hawaiian Islands have been forged with fiery lava, a destructive as well as life-bringing force. BirdNote®’s Michel Stein reports on how this rocky archipelago became so abundant in life.

BirdNote®

The Birds and Plants of Hawaii

[A volcano erupting]

Massive volcanic eruptions brought forth the Hawaiian Islands from deep beneath the sea. [A volcano erupting]

How did these remote islands of lava rock grow lushly green with plant life?

[Waves] Birds played a vital role. Birds like the Pacific Golden-Plover we’re hearing now. [Pacific Golden-Plover calls]

Three-quarters of Hawaii’s native flowering plants probably came from seeds that hitched rides with birds. [Pacific Golden-Plover calls]

Plant seeds travel with birds in several ways. Sticky or barbed seeds adhere to the feathers — much like the seeds stuck in your socks after a walk in a weedy field. Other seeds travel in mud caked on a bird’s feet. And still others cross the ocean in the stomachs of birds. [Pacific Golden-Plover calls]

The ʻakiapōlāʻau is an endangered species of Hawaiian honeycreeper endemic to the island of Hawaii that eats insects in the bark of trees, like a woodpecker. (Photo: © Brooks Rownd)

The bird-borne seeds that sprouted in Hawaii evolved into more than a thousand new species. The most likely seed-carriers were strong fliers like plovers or tropicbirds, which travel thousands of miles across the Pacific. [Red-tailed Tropicbird sounds] Or perhaps the seeds hitched a ride on the ancestors of this Akiapola’au we’re hearing — caught in a storm and blown to the Hawaiian Islands. [Akiapola’au calls]

Learn more at BirdNote.org.

###

Bird audio provided by The Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Pacific Golden-Plover recorded by W. Ward. Red-tailed Tropicbirds recorded by C. Robbins.

Akiapola’au calls from honeycreeper-01

Assorted ambient recordings by Kessler Productions.

BirdNote’s theme music was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Chris Peterson

© 2015 Tune In to Nature.org November 2013/2017/2019 Narrator: Michael Stein

ID# 111307plants2HIKPLU SotB-hawaii-04-2011-11-20

https://www.birdnote.org/listen/shows/birds-and-plants-hawaii

BELTRAN: For pictures, soar on over to the Living on Earth website, loe.org.

Related links:

- Learn more on the BirdNote® website

- Hear the ‘I’iwi or scarlet honeycreeper’s song

- Watch an `Akiapōlā`au honeycreeper hunt for grubs

[MUSIC: Abby Rabinovitz, “Tumbadito” on Flute Stories, by Abby Rabinovitz, Northeastern Popular Arts Records]

DOERING: Just ahead – the tiniest element in the universe is generating energy on Earth and new technologies. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Earl Hines, “Mack the Knife” on Tour de Force, by Weil, Brecht & Blitzstein, 1201 Music]

Beyond the Headlines

Presidential candidate Vivek Ramaswamy is a staunch climate denier. (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

It's that time now for a look beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra, our Living on Earth contributor. Peter joins us from Atlanta, Georgia. Hey there, Peter, what do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Paloma. Looking back to last month's Republican presidential candidate debate in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. There was even a question about climate change. Most of the candidates hemmed and hawed and didn't say very much. Only one was an outright climate denier. And that's the political newcomer, Vivek Ramaswamy. He said climate change is a hoax. But the fact that there was a question has heartened many young conservatives who see it as a point of vulnerability when the Republicans either deny or don't talk about climate change at all.

BELTRAN: So young Republican voters are really pushing the conversation around climate change for their party. Interesting.

DYKSTRA: Well, that makes sense, because they're the ones that are going to have to live with it. And what we've seen this year with wildfires, those atmospheric rivers that are dumping rain in places that don't get much rain, all of the storms, typhoons, hurricanes, and the fact that these things are on the upswing in precisely the way that climatologists have predicted for 30 years, it's becoming a harder and harder issue to ignore. And young conservatives want to see it at least get in the discussion, as we approach the 2024 presidential election, elections of the entire House of Representatives and 1/3 of the Senate in November 2024.

BELTRAN: And, you know, there's this recent poll between the Washington Post and the University of Maryland, that says that 35% of Republicans say that climate change is a major factor in extremely hot days compared to around 85% of those who lean Democrat.

DYKSTRA: Well, it shouldn't be a political issue at all. It's a weather and climate issue. And it's a multi multi billion dollar issue. And someday, hopefully not in the too distant future, American politicians will be on the same page and realize that this is a problem. We're already late in dealing with, we don't want to get much later.

BELTRAN: What else do you have for us, Peter?

White-tailed deer have tested positive for COVID, sparking concerns about the disease bleeding over from animals to human populations. (Photo: Tom Murray, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

DYKSTRA: A little potential come back for COVID. It has vanished from the news, although it's still killing people. But there's a research project in Ohio, that's been testing white-tailed deer for COVID infections. They tested over 1500 deer using nasal swabs. And all of us who got a nasal swab test for COVID know how much fun that is. And in about 10% of the deer tested COVID positive. It's something that needs to be watched. Because deer can be a vector, not just to other wildlife, but even back to humans in a potential return of the intensive and tragic toll that COVID inflicted throughout the world in the last few years.

BELTRAN: Yeah, we'll definitely need to come back for updates on that research. What do you have for us from the history books?

DYKSTRA: 1988, 35 years ago, it's hard to believe that the Yellowstone fire, that massive wildfire, took place 35 years ago. Paloma, where were you 35 years ago?

BELTRAN: I wasn't yet on this earth, Peter. Where were you?

DYKSTRA: I was in Washington DC. An argument could be made that that's really not on this earth either. But from there, we watched the Yellowstone fire overtake a lot of the park. The fire reached the perimeter of Old Faithful, that geyser that is the most known symbol for Yellowstone. Firefighters were not able to save 19 outbuildings around the Old Faithful complex, but they did save the vulnerable and wooden, Old Faithful Inn to continue serving tourists who come to see not just the geyser, but the beauty of this park.

The Old Faithful Inn stayed standing during the 1988 North Fork Fire. (Photo: Jim Peaco, National Park Service, Public Domain)

BELTRAN: Amazing, Long live Old Faithful and long live Yellowstone.

DYKSTRA: And let's be faithful to our national parks.

BELTRAN: Well, thank you, Peter. Peter Dykstra is a Living on Earth contributor and we'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, thanks a lot, Paloma. Talk to you soon.

BELTRAN: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth website. That's LOE.org.

Related links:

- CNN | “As Young Conservatives Try to Get Climate on the Agenda in 2024, Denial Takes the Spotlight Instead”

- Forbes | “Latest COVID Twist: Coronavirus Is Spreading in Deer, Study Finds—And Many Are Getting It from Humans”

- Learn more about the Yellowstone wildfire in 1988

[MUSIC: Leo Kottke, “Twilight Time” on Live, by Buck Ram, Marty Nevins and Al Nevins, On the Spot/A Division of Private Music]

Hydrogen Fueled Future

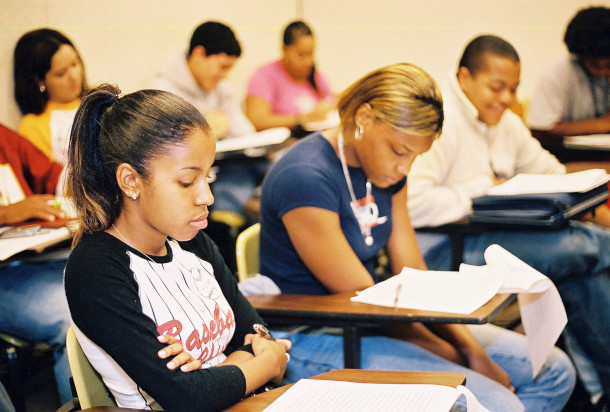

These electrolysers from Giner, Inc split the bonds of water to produce hydrogen and oxygen. (Photo: Robin Lubbock, WBUR)

DOERING: Ok Paloma, in honor of the start of the school year, you ready for a pop quiz?

BELTRAN: [nervous laugh] oh-oh kay??...

DOERING: How much do you remember from gen chem?

BELTRAN: Oof, I wasn’t a big fan of chem…

DOERING: Me neither, truth be told but maybe you remember the atomic number of Hydrogen?

BELTRAN: Let me see… hmm… would that be… number 1?

DOERING: Yep! That’s an A+

Hydrogen is Atomic Number 1 on the periodic table because it’s the smallest, lightest element in the universe. It’s also by far the most abundant, making up about three-quarters of all matter. And if you combine hydrogen and oxygen in a fuel cell, you get water and clean, green electricity [Editor's Note: that's true if the hydrogen was derived using carbon-free energy]. This chemical reaction is fueling visions of future, carbon-free flights and voyages of fantasy that could soon become reality. Our friend Bruce Gellerman first produced this story for WBUR-Boston.

GELLERMAN: 150 years ago, Jules Verne captured the world's imagination with his science fiction novel, “Mysterious Island”, continuing the journey of the Nautilus submarine.

CAPTAIN NEMO: I'm Captain Nemo. Welcome to my island.

[“MYSTERIOUS ISLAND” MUSIC]

GELLERMAN: Verne wrote that "water will one day be employed as fuel," that the separated elements, hydrogen and oxygen, quote, "will furnish an inexhaustible source of heat and light, of an intensity of which coal is not capable.” Pure hydrogen is a powerful energy source and it is the most abundant element in the universe. And over the decades, the dream of harnessing hydrogen to transform the world's economy has persisted in the hearts and minds of scientists and politicians.

SOVACOOL: And the term in the communications studies literature and psychology is, "they came to a symbolic convergence.”

GELLERMAN: Benjamin Sovacool, Director of Boston University's Institute for Sustainable Energy, is author of the book: "Visions of Energy Futures.”

SOVACOOL: Symbols, ideology, values and language all coalesced around this miraculous vision of what a hydrogen economy would do, and the fantasy itself was very very real, and it was very effective at shaping funding patterns, and at shaping even scientific discourse.

GELLERMAN: Sovacool recalls President George W Bush's 2003 State of the Union Address.

BUSH: Tonight I am proposing 1.2 billion in research funding, so that America can lead the world in developing clean hydrogen-powered automobiles.

[APPLAUSE SFX]

SOVACOOL: Whenever anyone talks about a hydrogen economy, they’ll usually say things like, "well, and its only output is water."

[APPLAUSE SFX]

BUSH: A simple chemical reaction between hydrogen and oxygen generates energy, which can be used to power a car, producing only water, not exhaust fumes.

While most of the hydrogen produced today uses fossil fuels, green hydrogen uses renewable energy sources. (Photo: Robin Lubbock, WBUR)

GELLERMAN: Chances are you're not driving a hydrogen-powered car, at least not yet.

There are several good reasons. On earth, most hydrogen is chemically bonded to oxygen to form water or to carbon to make fossil fuels. And the procedure most often used emits a lot of climate disrupting gases. Sovacool says scientists have color-coded hydrogen according to the kinds of energy used in the separation process.

SOVACOOL: So there’s gray and black, which is fossil fuel, there’s blue which comes from natural gas, there’s green which comes from renewables, and there’s pink which comes from nuclear power.

GELLERMAN: Today, most of the hydrogen we separate today is black. Green is the kind you want, using electricity generated by renewable solar and wind power. But until recently, it wasn't practical or profitable to make large amounts of green hydrogen.

Scientists at the Massachusetts-based R&D company, Giner Inc, have been working at it for 50 years.

BELT: We operate at the frontiers of electrochemical technologies, pushing the envelope. We're actually the best in the world at that.

GELLERMAN: Andy Belt is Giner's CEO. He says the company has been perfecting the technology to split water efficiently. It's a process known as electrolysis. It's done in a device called an electrolyser.

BELT: In the guts of the electrolyser, where the magic happens, you combine water with electricity, and you break the bonds of water and out comes hydrogen and oxygen. And that's the magic that goes on in the center of an electrolyser.

GELLERMAN: Inside the devices are thin membranes, coated with precious metals. They enable the electrochemistry magic to work. Low cost wind and solar electricity make the process green.

BELT: Because of advances in renewable energy, because of the advances in electrolysis technologies, it’s absolutely feasible to see that within 10 years that we could have a massive piece of the energy infrastructure based on green hydrogen.

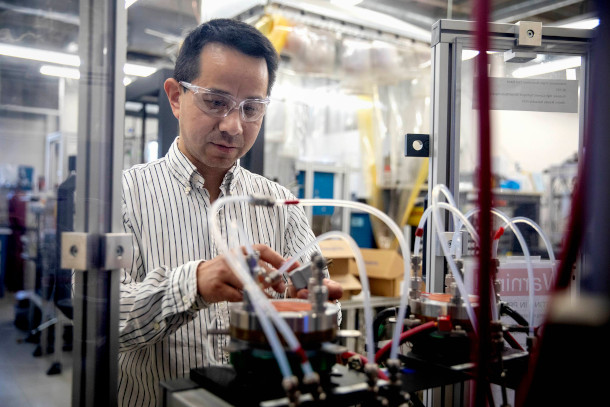

Andy Belt, CEO of Giner, Inc, says that the cost of producing green hydrogen is declining. (Photo: Robin Lubbock, WBUR)

GELLERMAN: Belt says producing green hydrogen is becoming more cost effective as the price of generating electricity from solar and wind declines. Today, in many places the renewable energies are cheaper than burning natural gas and coal.

BELT: So if I can buy electricity at 2 cents per kilowatt hour and make hydrogen with my electrolyzer, the cost of electricity to make a kilogram of hydrogen is now a buck or less.

GELLERMAN: And that's one of the Department of Energy's goals. Cut the cost of separating hydrogen by 80 percent in a decade. It would make the price of energy from hydrogen equal to gas selling at about a dollar a gallon. Boston University's Benjamin Sovacool says that price doesn’t even consider the hidden costs of burning fossil fuels on the climate and human health.

SOVACOOL: You start pricing coal accurately, hydrogen’s much more competitive. You start pricing things like oil more competitively, hydrogen and renewables are more competitive. Energy’s cost does not match its price.

GELLERMAN: Sovacool still has doubts about the future of a green hydrogen economy, but he's cautiously hopeful the proposed federal hydrogen hub program could work.

SOVACOOL: I'm slightly skeptical, but I think there's a lot more rationality for hydrogen here. If the government were to continue to create the right policy architecture, hydrogen transitions could very much occur in the next 10 or 15 years. They won't happen by themselves in the market, but if they had the right sort of incentives and policy, I could see it happening.

Bill Spellane is Chief Operating Officer of Alakai Technologies, a company hoping to make hydrogen-powered air travel a reality. (Photo: Bruce Gellerman, WBUR)

GELLERMAN: It’s already happening in Massachusetts, where engineers with Alakai Technology are unlocking hydrogen’s power.

[HANGER SFX]

GELLERMAN: In a large hanger at Minute Man Air Field in Stow, Mass workers are assembling prototypes of clean green, flying machines unlike any that have flown before.

SPELLANE: So we’re building a hexacopter that will fly up to 400 miles, a thousand pounds of people or cargo, we’re hydrogen powered, not battery powered. We do hydrogen.

GELLERMAN: Bill Spellane is Chief Operating Officer of Alakai Technologies. He's standing under one of the six rotor blades of the company's Skai aircraft, spelled S-K-A-I. The hydrogen-electric hexicopter looks like a futuristic minivan that can take off and land vertically.

Aboard SKAI will be cyclinders filled with liquid hydrogen that's warmed to a gas and pumped into fuel cells, where the hydrogen will combine with oxygen from the atmosphere, producing H2O and electricity.

There are no fossil fuels, no climate disrupting emissions.

SPELLANE: Hydrogen plus oxygen equals water and energy. We use the energy, expel the water. That’s our emissions, water.

GELLERMAN: That’s it?

SPELLANE: That’s it, water.

GELLERMAN: Hydrogen packs a powerful energy punch, pound for pound, gallon for gallon. Three times more energy than jet fuel. And refueling takes just a few minutes.

SPELLANE: For an aviation application, hydrogen is compelling. You need to store a lot of fuel in order to fly a vehicle. Hydrogen provides that to you. We have fewer moving parts, the vehicle is simple to operate, simple to maintain. You don’t have to pay as much in maintenance.

GELLERMAN: Spellane says the hexacopter is stable in high winds, has room for a pilot and 4 passengers, can be used for air taxi and cargo services, medical flights, and disaster relief. Top speed? 115 miles per hour. Rotors mounted on the 6 arms, stretch skyward, each powered by an electric engine.

SPELLANE: If you want to tilt forward, the rotors in the back speed up, the ones in the front speed down, your attitude changes, and now you can fly forward. If you want to go right, you speed up the left side, turn down the right side, you roll right.

[RADIATOR FAN SFX]

GELLERMAN: Technicians test a radiator fan aboard one of three SKAI prototypes. Today 50 engineers, many ex-military aviators and engineers, work at Alakai.

Bill Spellane, speaking with an understated passion, says he’s worked 7 days a week for the last 5 years.

Alakai Technologies’ hexacopter is powered by hydrogen fuel cells, which emit only water. (Photo: Tamara Willsie)

SPELLANE: This is the second vehicle ever built, R&D vehicle. Pure iron bird test vehicle.

GELLERMAN: Do you have a name for it?

SPELLANE: We call it Prototype 0.5.

GELLERMAN: No endearing term, no like Bluebird 7, or something like that, or Hydro 3?

SPELLANE: We are engineers, sir. Prototype 2.

GELLERMAN: Spellane hopes a public demonstration of the hydrogen-powered hexicopter takes place soon. Then, he predicts, things are going to take off. But actually, hydrogen fuel cells have been around for 60 years, when a breakthrough launched the technology into orbit, literally.

BELT: And that was a technology developed by GE in Lynn, Massachusetts, for the Gemini space program..

GELLERMAN: Andy Belt, head of the hydrogen research company Giner, says back then, General Electric engineered fuel cells that were reliable, powerful and safe for space, and beyond.

BELT: That was extraordinarily exciting. Fuel cells, hydrogen, were going to be the future of not just of space travel, but transportation in general.

GELLERMAN: But so far hydrogen hasn't fueled our general transportation needs. It may be the most abundant element in the universe, but isolating hydrogen has been expensive and climate disruptive. Clean renewable sources of electricity could change the equation. Large solar and wind projects may make it possible to power electrolysis to split water and produce green hydrogen on an industrial scale. Judith Lattimer, a senior project scientist at Giner, looks to the horizon for a way to make hydrogen low cost and climate friendly.

LATTIMER: What we’re working on is to couple offshore wind turbines directly with electrolyzers, in order to produce hydrogen offshore for fueling ships, or you can use a pipeline to get it on shore.

GELLERMAN: Either way would be a sea change. In fact, “Sea Change “ is the name of a green hydrogen powered ship now being tested in Puget Sound, Washington State.

RATTI: We are turning hydrogen into electrons, into electricity, through a fuel cell, without the carbon, which is kind of incredible.

GELLERMAN: Pace Ratti is founder and CEO of Switch Maritime, developer of Sea Change. He says the 70 foot vessel, powered by hydrogen fuel cells, will soon start ferrying passengers across San Francisco Bay. Ratti has spoken with other seafaring companies. He won’t discuss specific deals, but suggests they're in the works here.

RATTI: There’s going to be a lot of exciting projects on the east coast.

GELLERMAN: The green hydrogen economy, powered by solar and wind energy, is picking up speed as a replacement for fossil fuels. And Pace Ratti says the developments haven’t gone unnoticed.

RATTI: Traditional oil and gas companies are trying getting into this game as well, you know, seeing hydrogen as the next commodity they want to be selling in addition to or in place of oil and gas.

[CHEVRON ADVERTISEMENT MUSIC]

CHEVRON:What lies on the horizon, the answers lie beyond the roads we know.

GELLERMAN:Chevron oil advertised its hydrogen hopes on air.

CHEVRON: We recognize that energy demand is growing and the world needs lower carbon solutions to keep up.

The hexacopter can fly at up to 115 miles per hour while carrying a pilot and four passengers. (Photo: Robin Lubbock, WBUR)

GELLERMAN: Chevron, ExxonMobil, and Shell Oil have joined forces with other energy interests to develop a large-scale hydrogen hub along the US Gulf Coast.

They are competing for a chunk of the 9.5 billion dollars in hydrogen funding set aside in the federal Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. But while big oil has big plans, building a green hydrogen economy will require tens upon thousands of small companies developing innovative products like the ship Sea Change and Alakai’s SKAI hexacopter.

[HEXICOPTER SFX]

GELLERMAN: The unique flying machine is now going through the F-A-A certification process. Watching is company COO Bill Spellane, who stands in a field as a test pilot puts the hydrogen powered vehicle through its paces.

SPELLANE: It’s quieter than a helicopter, it’s quieter than a turbine aircraft. It’s quieter than the piston aircraft that also take off at this airport. Is it something you can sleep under? No, but you be the judge of how loud it is.

[HEXICOPTER SFX]

GELLERMAN: And slowly, surely, the hydrogen powered hexacopter lifts off the ground.

For a century and a half, the green hydrogen economy has been predicted by novelists, researched by scientists, and hyped by politicians. But as the global climate crisis worsens, the technology advances. China, Saudi Arabia and Brazil are among the countries investing billions to produce green hydrogen, their ambitions generating real hope for a future imagined long ago by science fiction writer Jules Verne.

[MUSIC]

GELLERMAN: For Living on Earth, I’m Bruce Gellerman.

Related links:

- WBUR | “Moving Hydrogen from Hype to Hope”

- WBUR | “Freeing—and Capturing—Hydrogen in Mass.”

- WBUR | “Going with Hydrogen, by Land Sea or Air”

- Giner, Inc.

- Alakai Technologies website

- The Switch Maritime website

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Tall Journey”]

BELTRAN: Next time on the show, marine protected areas in Turkey show the power of setting aside some space for nature.

KIZILKAYA: So it's not that difficult. You know, we're talking about 1% of the ocean's surface under protection right now. You know, if we can increase this to 20 in the real sense, we could save the entire future of oceans, you know, marine biodiversity and the fisheries at the same time.

BELTRAN: That’s next time on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Tall Journey”]

BELTRAN: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Josh Croom, Swayam Gagneja, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Sarah Mahaney, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari. We say goodbye to Clare Shanahan and Maddie Goldberg this week. Thanks for all your hard work this summer!

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. Special thanks this week to WBUR Boston. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments at loe dot org. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Jenni Doering.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth