January 5, 2024

Air Date: January 5, 2024

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Climate is a Public Health Emergency

View the page for this story

The climate emergency is creating a public health emergency by increasing risks for heat stress, vector-borne diseases, traumatic injuries and more. Dr. Vanessa Kerry is the World Health Organization Special Envoy for Climate Change and Health and joins Host Aynsley O’Neill to discuss these risks and the importance of fortifying health systems against climate impacts. (10:09)

Key Court Cases of 2023

View the page for this story

2023 saw some notable environmental decisions in U.S. federal and state courts, from the Supreme Court’s removal of some wetlands protections to the landmark win for youth plaintiffs in a Montana climate case. Law professor Pat Parenteau joins Host Steve Curwood to explain what these decisions could mean for environmental law and policy going forward. (13:06)

Environmental Figures We Lost in 2023

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Household names like Jimmy Buffett, Harry Belafonte, and Senator Dianne Feinstein were among the environmental figures who passed away in 2023. Living on Earth Contributor Peter Dykstra and Host Aynsley O’Neill remember these and some other less recognized people who made contributions to environmental causes. (05:42)

Our Fragile Moment

View the page for this story

2023 is likely to go down in history as the hottest year ever seen by humans. But we still have a chance to rein in global warming before it runs too hot for our civilization, says UPenn Professor Michael Mann. He joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss his recent book Our Fragile Moment: How Lessons from Earth’s Past Can Help Us Survive the Climate Crisis. (16:21)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

240105 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood, Aynsley O’Neill

GUESTS: Vanessa Kerry, Michael Mann, Pat Parenteau

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

Human health and the health of the planet are closely linked.

KERRY: We know that over 8 million people a year are dying from air pollution. Over 5 million of those deaths are from fossil fuels. Climate change is driving increases in poor health, whether it is for infectious diseases, mental health, pretty much everything you could imagine is being impacted by climate change.

CURWOOD: Also, while many governments greenlight fossil fuels, some courts put on the brakes.

PARENTEAU: The Held case is going to be the first time I think we will see a solid court decision recognizing a constitutional right to a stable climate. Once the courts enter the arena of climate law, what exactly are they going to start ordering governments to do?

CURWOOD: That and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Climate is a Public Health Emergency

The 2022 floods in Pakistan submerged one third of the country, affecting 33 million people, half of whom were children. The floods damaged most of the water systems in affected areas, forcing more than 5.4 million people to rely solely on contaminated water from ponds and wells. (Photo: Abdul Majeed, European Union, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

O’NEILL: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

Just last month COP28 in Dubai became the first climate summit to observe Health Day. 124 countries endorsed the Declaration on Climate and Health, sounding the alarm on the severe public health and wellness implications of the climate crisis. The World Health Organization or WHO estimates that by the end of this decade the cost of the climate impact on health will be between 2 and 4 billion dollars per year. But that figure is surely an underestimate because it doesn’t include massive climate burdens on agriculture, water, and sanitation, which all shape public health. And WHO says the health sector receives just one half of one percent of global climate financing. In light of that shortfall, COP28 included an announcement of 1 billion dollars towards climate and health, though some of that funding was already committed before the talks began. Dr. Vanessa Kerry is the WHO Special Envoy for Climate Change and Health and helped organize Health Day. She also leads the non-profit Seed Global Health, which works primarily to strengthen medical systems in Sub-Saharan Africa. Dr. Kerry joins us now. Welcome to Living on Earth!

KERRY: Thank you very much. It's really a pleasure to join you.

O'NEILL: Now, a statistic I've seen is that according to the World Health Organization, between 2030 and 2050, climate change is expected to cause approximately 250,000 additional deaths per year from things such as undernutrition, malaria, cholera, diarrhea and heat stress alone. Can you walk us through the connection between the climate crisis and these particular diseases?

KERRY: Absolutely. The climate crisis is a health crisis. It is the 250,000 deaths a year is probably an underestimate. The data has been changing rapidly. We're learning every day, we're playing catch up on exactly how we're being impacted from climate change in terms of our survival, our human health and our well being. There are very direct impacts of climate change on human health in terms of extreme weather events, whether it is deaths from drowning, wildfires, air pollution, if it is changes and increases in infectious diseases, non communicable diseases that are being driven. Just to give a very concrete example, the floods in Pakistan and 2022 led to four times the rates of malaria, after the floods, including in provinces where malaria had been almost completely knocked out. We're seeing this in non communicable diseases, data just came out just before COP that told us that over 5 million deaths a year are directly attributable to fossil fuel use and the air pollution from fossil fuels. We're seeing this in pregnancy. But we're also seeing indirect impacts that are happening on human health from climate change, which is, for example, that we're seeing changes in dry seasons in drought, like we're seeing in the Horn of Africa, food insecurity, we're seeing changes in access to water. We're seeing this in terms of people's livelihoods and their abilities to go to work because of extreme heat. We're also seeing it in terms of gender based violence. We've heard reports of young girls who have to walk farther and farther now for water in Kenya, who then are at increased risk of gender based violence and sexual assault because of the distance or traveling. So what we're dealing with is quite literally in every possible way, climate change is impacting our daily experience today, here and now. And our ability to live healthy lives, and to have the opportunities that we want for ourselves and our family.

Seed Global Health midwife educator assessing a pregnant woman at Makeni Hospital in Sierra Leone. (Photo: Courtesy of Seed Global Health)

O'NEILL: Now, there are all these overarching issues that tie together climate and health. But I want to think about some of the immediate impacts that we might be seeing. If we reduce fossil fuels, if we cut fossil fuel emissions, how immediately can we start to see health benefits from that?

KERRY: It is urgent that we absolutely commit to a phase out of fossil fuels. And it is urgent if we're going to keep to the Paris 1.5. And certainly, we're going to protect human health. So we did talk about the study that talked about the fact that there's over 5 million deaths a year that are directly related to fossil fuel use. But what we know is there are scientific studies, for example, in the inner cities and in communities and other places that show that when you actually get rid of gas or fuel burning buses and pollutants, you can actually reduce asthma attacks hospital and emergency room visits. And you can start to see direct benefits and health just in the immediate moment of reducing fossil fuels. But fossil fuel use is actually driving our extreme weather. So as long as we are burning fossil fuels, and we are continuing to see an increase in greenhouse gas emissions, we are going to continue to drive the extreme weather that is leading all the health bad outcomes that we're seeing. So some of it is absolutely immediate, but some of it will drive a change that might take a little bit longer to see. But the important thing to remember is there is an urgency to reducing fossil fuel use today, we may not see all the direct outcomes for a year or two years until we start to really see the crest in terms of the greenhouse gases that we're doing. But we will be in completely the wrong direction and we will be accelerating the number of deaths and we will be accelerating the harm if we do not commit to a phase out of fossil fuels today.

O'NEILL: Now Dr. Kerry, your organization Seed Global Health works with nurses, midwives and physicians in Malawi, Sierra Leone, Uganda, Zambia, how have you seen the fallout from the climate crisis and the work that you do in that field?

Health workers at Mulago National Referral Hospital participating in an Ebola infection prevention and control training in Uganda in 2022 following the Ebola outbreak there. (Photo: Courtesy of Seed Global Health)

KERRY: See Global Health got involved in the climate change discussions because we have felt very directly the impacts of climate change in the communities where we work and it's made our job harder. As we have trained over 34,000 healthcare workers over the last decade that are in service to catchment areas of about 73 million people. What we have found is that extreme storms in Malawi that are more severe happening more frequently lasting longer, are making it harder for the healthcare workers be trained to do their job. There's more malaria at the height of the malaria season. There's more malaria when it's not Malaria season. We're seeing bridges washed out. I mean, a colleague of ours, Chauncey Banda, who's a midwife in the Sonjay district in Malawi, ended up having to help the government, you know, advocate for the government to have to set up new birthing centers, that Seed ended up supporting to help stand up because the bridges washed out to the existing birthing centers. And it turns out that when you're in a climate crisis, or when you have storms, women go into preterm birth more frequently. So this has a very real impact if you can't have continuity of services. Together, we ended up working to open these facilities such that C sections could be provided, and that women could have that continuity of care. And not a woman or child died in the wake of some of these storms after they lost their original facility. But that makes our job harder, that's more work, when we could be delivering primary care services or ensuring services, you know, elsewhere. And so we're finding that we're seeing more and worse health outcomes because of climate change. It's the same in Uganda, it is the same in Sierra Leone, it is the same in Zambia, it's across the continent, and it's across the world. It's here in the United States. So we know we're going to need more workforce to meet the challenges from climate change, we're going to need health systems that can be resilient to the climate changes that are happening to keep delivering services. And we need to adapt to these changes here and now or we're going to lose more lives.

Vanessa Kerry is the director of the Program in Global Public Policy and Social Change in the Department of Global Health and Social Medicine at Harvard Medical School. She is also the founder and CEO of Seed Global Health as well as a physician at Massachusetts General Hospital and serves as the associate director of Partnerships and Global Initiatives at the hospital’s Center for Global Health. (Photo: Courtesy of Seed Global Health)

O'NEILL: Dr. Kerry, what inspired you to get into this world of strengthening global health care?

KERRY: I grew up in a house a public service with both my parents very, very committed to being global citizens, and to being advocates for those that maybe couldn't advocate for themselves. And so as I was always interested in going into medicine, I very much brought some of those experiences forward with me into my medical career. When I was 14, I had the opportunity to travel to Vietnam back before sort of we normalize relations for the country and saw a level of poverty that was just shocking at the scope, the scale and the degree of the poverty that I saw. And I didn't know what to do with it at age 14. But I held on to it so that when I went to medical school became very clear to me that my medical career needed to integrate some of that experience that I had had in Vietnam and actually, it had the opportunity to see in other countries as I had lived and worked in other places. And it put me very much on a path to realize that, you know, at that time, it was 2,000 but I've been saying the same thing now for 20 years, so that I can still say unfortunately, in 2023, it is unacceptable, that there are two such different standards of medical care in the world. And we have the technology, we have the wherewithal we have the resources were just not making the choice to provide the services to people. And that is just fundamentally unacceptable. So my career and my colleagues that I have the privilege of working with whether it's in any of our African countries or globally or with the team at Seed, we are all committed to that same mission, to really close that gap with every capability that we can to make sure that there's a strong and robust healthcare workforce to deliver services to hold someone's hand when they die. So they don't die alone. And they die with dignity to ensure that a woman when she's hemorrhaging, childbirth, has that bag of blood hung for her son, you can save her life. To make sure that we're diagnosing patients appropriately, managing them appropriately and that the medicines are available to be able to treat them. So for us climate change is just exacerbating that gap even more and driving it even further, which is what has brought me to this place of now getting engaged in the climate health Nexus because the work that we spent a decade doing is all at risk if we don't step up to this moment with a new and accelerated commitment and to bring others on board to meet this moment.

O'NEILL: Dr. Vanessa Kerry is the CEO of Seed Global Health and the WHO Special Envoy for Climate Change and health. Vanessa, thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

KERRY: Thank you very much for having me. It's a pleasure to be able to connect.

Related links:

- Learn more about Dr Vanessa Kerry’s appointment as WHO Director-General Special Envoy for Climate Change and Health

- Learn more about Seed Global Health

[MUSIC: Linny Hoo, “Original Song Glides Chalamanda” Single, Malawi Music]

CURWOOD: Coming up, remembering the environmental impacts of some of those we lost in 2023. That’s just ahead. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Jimmy Smith/Thornel Schwartz/Donald Bailey, “Willow Weep for Me” on At the Organ, Volume 3, by Ann Ronell, Blue Note Records]

Key Court Cases of 2023

The United States Supreme Court reversed five decades of legal precedent when it cut wetlands protections in the Sackett v. EPA case. (Photo: Susan Melkisethian, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

O’NEILL: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. 2023 saw some notable environmental decisions in U.S. federal and state courts, and this year brings the prospect of even more. So of course, we called up Pat Parenteau, Emeritus Professor of Law at Vermont Law School. Happy New Year, Pat!

PARENTEAU: Hey, Steve, Happy New Year to you. Good to be with you, as usual.

CURWOOD: Always glad to have you, Pat. Hey, let's take a moment now to go over some of the crucial environmental court cases from last year. What happened in the United States in 2023 that we'll be seeing the consequences of this year, 2024?

PARENTEAU: Well, probably leading the list would be the Supreme Court's decision in the Sackett case involving the wetland in northern Idaho where the court has now redrawn the geographic scope of the Clean Water Act and greatly reduced it. And we haven't yet seen the full implications of this decision. But it's rolled back the power of the federal government to protect wetlands and small streams all across the country. By some estimates, as much as 50% of the remaining wetlands in the country are now at risk, because they now no longer have federal protection. And of course, EPA and the court had no choice but to accept the ruling of the Supreme Court in Sackett. And so they've now issued a rule, basically saying our jurisdiction now is greatly limited. There's still some questions about just how many streams are still covered by federal law and how many are not, and what the fate of those streams and their associated wetlands are going to be, particularly in states where there is no gap-filling state law to replace the loss of federal protection with state protection. And that is true in about 27 states across the country. So in 2024, what we're going to see in water quality and wetlands protection is, frankly, a lot of chaos. I mean, wetlands are the nature's kidneys, as they're called by the scientists, meaning they cleanse a lot of the pollutants that would otherwise get into water supply.

Wetlands conservation is critical to keeping drinking water clean, as well as combatting biodiversity loss and climate change. (Photo: Jim Liestman, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

And EPA has done extensive studies showing the connection between protection of streams and wetlands, and drinking water supplies. So when you take away nature's protections for water quality, you have to replace it with artificial means of protecting it. And those costs have not yet been calculated, either. A lot of people were saying Sackett was supposed to resolve the question of federal jurisdiction, but it certainly doesn't resolve the question of what's the fate of these waters that are no longer subject to federal law, they've been subject to federal law for over 50 years. I mean, this is very similar, of course, to the Dobbs decision, overturning Roe v. Wade. 50 years of law is now no longer the law of the land. So, a lot of uncertainty around wetlands and water quality in 2024.

CURWOOD: All right, hey, let's talk about efforts to bring the government to action when it comes to climate disruption. There are a couple of key cases that are going on, Pat, what about the one in Montana?

PARENTEAU: Yeah, so this was a breakthrough case, precedent-setting case where Our Children's Trust, which represents youth plaintiffs in cases, frankly, in every state in the United States, finally won a major victory in Held v. The State of Montana, where a lower court in Montana ruled for the first time that there is a constitutional right, based on state constitutional law, to basically a stable or safe climate system. And the Montana court ruled that the state of Montana's energy policy was violating the youth plaintiffs' constitutional rights under the Montana constitution, because it was forbidding the state agencies from considering the effects on the climate system from continued production of oil and gas and coal. And of course, Montana is one of the major producers of fossil fuels in the country.

Youth plaintiffs Badge Busse, Mica Kantor, and Eva L. are cheered on by supporters as they arrive for their second day of the Held v. Montana trial in June 2023. (Photo: Robin Loznak/Courtesy of Our Children’s Trust)

So now that case goes on appeal to the Montana Supreme Court. So we will see a decision probably this year from the Montana Supreme Court. The betting, I guess, I would say is that the Montana Supreme Court is likely to uphold Judge Seeley's decision in Held because she did such a great job of building a record to support her rulings and making the case that the state's policy was not only illegal, but stupid. I mean, telling agencies not to consider what the science is telling us is the effects of continuing to burn fossil fuels. That doesn't make any sense at all. So the Held case is going to be the first time I think we will see a solid court decision recognizing a constitutional right to a stable climate. So the question is going to be once the courts enter the arena, if you will, of climate law and climate remedies, what exactly are they going to start ordering governments to do? State governments, and a little later, we may talk about the federal government in the Juliana case as well. But right now, I think it's interesting to watch how these various state courts deal with these constitutional questions. And we're testing the limits of the power of the courts to deal effectively with a problem as massive as climate change.

Youth plaintiff Levi Draheim rides on the shoulders of a supporter as he makes his way to a rally following a hearing in the Juliana v. United States climate change lawsuit. (Photo: Robin Loznak/Our Children’s Trust)

They're not going to order an immediate decarbonization, right, of the entire economy, the energy system, the transportation system. But what they will do, perhaps is begin to demand that the government start looking more at specific actions, not just promises of future decarbonisation like net zero by 2050. We see that terminology used a lot in climate law. It doesn't mean much. The question is, what are you doing today, to reduce emissions and to promote renewable energy, solar and wind and battery storage, and so forth? So we will see, I think starting in 2024, how far are courts going to be willing to go in ordering specific actions by the government or ordering the government to stop promoting fossil fuel development. I mean, the United States is the world leader in both oil and gas production. And we're still building new export terminals for oil and gas. Part of it's related to the war in Ukraine, of course, but it's a bigger economic question than that. So lots to look forward to on that front in 2024.

CURWOOD: Yeah, talk to me about the federal case, the Juliana case. That's in Oregon, but it's in federal court. What's going on with that?

PARENTEAU: Yeah, so that case was dismissed by the Ninth Circuit now almost two years ago. And so now it's back before the Oregon federal district court in Eugene. And back before Judge Ann Aiken, who was the judge in the original Juliana case. Judge Aiken has just issued a decision within the last few days, denying the Biden administration's motion to dismiss the case throw it out, and ruling that no, the court has jurisdiction, it's going to allow the youth plaintiffs led by Kelsey Juliana. And she is ordering the case to proceed to trial. The Biden administration is vowing to fight this and take it up to the ninth circuit and if necessary, probably all the way to the US Supreme Court and refusing to acknowledge that the court has any jurisdiction to have a trial on the federal government's actions and inactions dealing with climate change.

The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) is one of the largest national wildlife refuges in the United States. It is considered one of the country’s last untouched areas of wilderness. In 2023, the Biden administration canceled seven ANWR oil and gas leases that had been put in place during the Trump presidency. (Photo: Hillebrand, USFW, Flickr, Public Domain)

Of course, the Biden administration has done a lot. Done more than any administration, in fact. So you know, one of the puzzling things to me is, why doesn't the government just show up for trial and defend its record, if that's what it wants to do? And it could also point out that it's doing as much as the current law allows. And, you know, it's also trying to get Congress to pass new laws, it was very successful with the Inflation Reduction Act, which is the biggest investment in renewable energy and clean energy that we've ever seen. So, you know, the question is, why is the Biden administration digging in its heels and refusing to even have a trial to let the youth plaintiffs have their day in court? And, of course, the big question is, would a decision recognizing a constitutional right under the federal constitution to a safe or stable climate, would that survive ultimate review in the United States Supreme Court? The odds of that are long, obviously, with this very conservative court. But as Judge Aiken was saying in her recent decision, the plaintiffs here, the young people here have a right to make their argument and get a decision. That's what courts are supposed to do. When there's an allegation of a violation of fundamental constitutional rights, it's the job of the courts to say what the law is. And so that's what Judge Aiken has ruled. She is going, unless she's stopped, she's going to proceed to hear the case, hear the evidence, and issue a ruling on whether there's a constitutional right under the 14th Amendment, due process clause, to a safe climate system for the future of these young people.

CURWOOD: Now, Pat, you're the lawyer. I am not, but just to spin forward for a moment, if Juliana were to win at even the trial level, one of the remedies might be to say that the United States government has all this fossil fuel that it's spewing out into the air, that it has all these coal reserves, that it's saying, hey, it's gonna move ahead with what's in Alaska, and that at the very least, the government could stop making the situation worse.

PARENTEAU: Right.

CURWOOD: I wonder to what extent the Biden administration is concerned that there might be such a remedy type ruling that would, you know, go right in the face of the fossil fuel industry, which is so powerful in this country?

Pat Parenteau is emeritus professor of law at Vermont Law School and formerly served as EPA Regional Counsel. (Photo: Courtesy of Vermont Law School)

PARENTEAU: Yeah, I think that Biden administration faces a dilemma. On the one hand, I think it's fair to evaluate what they've been doing as the most aggressive policies we've seen. You have the president setting aside areas of high environmental value in Alaska, in public lands in the West national monuments, national parks, Chaco cultural area where there's a lot of oil and gas and saying, we're not going to continue to develop oil and gas around these high value areas in our country. But on the other hand, we are going to promote oil and gas development in the Gulf of Mexico, in certain places in Alaska, both because we are in a position where we can't simply stop producing oil and gas immediately. And also, because the laws on the books don't let us do that. Don't let us just declare, for example, a permanent moratorium on oil and gas development. And courts have ruled that the Biden administration can't do that. So Biden is in a bind, he wants to move as aggressively as possible towards cleaner energy sources, for example, electric vehicles, for example. But he's constrained in part by the law on the books, and in part by the reality that you can't simply turn on a dime and flick a switch and become clean and green overnight. So that's where we are. And these court cases are pushing the boundaries, pushing the government to do more of what it can do, and less of what it really shouldn't do and doesn't need to do. So, it's a difficult, complicated situation we find ourselves in. And the science is just getting more and more dire, the consequences are becoming more and more real every day. And so that's kind of where we are. And obviously the courts only have a limited role to play in all of this, but they do have an important role to play.

CURWOOD: Pat Parenteau is an emeritus professor of law at the Vermont Law School. Pat, thanks so much for your time and wisdom today.

PARENTEAU: Thank you, Steve.

Related links:

- Listen to our previous coverage of Sackett v. EPA with Pat Parenteau

- Listen to our previous coverage of Held v. Montana with Pat Parenteau

- Learn about the most recent updates in the Juliana v. United States case from Our Children’s Trust

[MUSIC: Tingerpalm*Bay, “Soul Wax” Single, Tingerpalm*Bay]

Environmental Figures We Lost in 2023

Biologist Roger Payne put the songs of humpback whales on billboard charts in the 1970s. (Photo: Pedro Szekely, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

O'NEILL: With me on the line now from Atlanta, Georgia is our Living on Earth contributor, Peter Dykstra. Together, we're gonna take a look back at some of the people that we lost last year in 2023. Hi there, Peter, who do you have for us?

Dr. Roger Payne brought Living on Earth to his ship, “Odyssey”, to explain whale songs in 2008. (Photo: Iain Kerr)

DYKSTRA: Well hi, Aynsley. And let's start with Roger Payne, the scientist who bridged the gap between science and art. He was the first to record the songs of the humpback whale. It was so popular in the 1970s that humpback whales made billboard charts of hit music. Roger Payne was 88.

O'NEILL: It's incredible seeing people who are able to incorporate environmental messages in their artistry, in their music. Do you have anybody else like that, Peter?

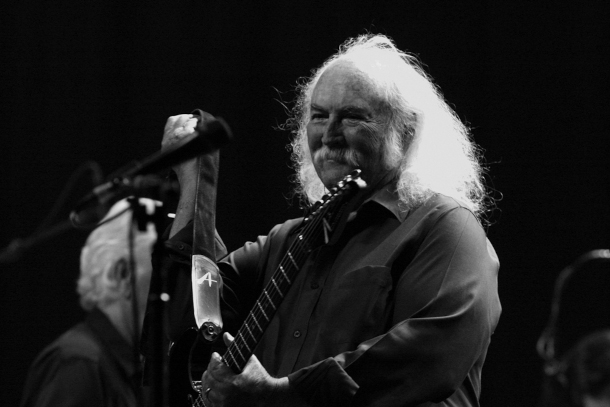

David Crosby’s song, “To the Last Whale,” warned of the consequences of commercial whaling. (Photo: Eva Rinaldi, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Couple of giants in music from that era. They devoted time, talent and cash to environmental causes. David Crosby's song, "Wooden Ships" told of a grim post-apocalyptic world, his song, "To the Last Whale," which he did with Graham Nash, warned of the consequences of converting our largest animals into some mundane commercial goods. Crosby was 81. Another huge artist was Jimmy Buffett. He died this year at age 76. He had a huge following of hedonistic "Parrot Heads" as they call themselves. But offshore, Jimmy Buffett's passions were drawn to protecting corals and sea turtles and manatees.

On and off stage, Jimmy Buffett advocated for the protection of coral reefs, sea turtles, and manatees. (Photo: Steven Miller, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

O'NEILL: Sadly this year, we also lost Harry Belafonte, known for songs such as, "Day-O (The Banana Boat Song)" or "Jump in the Line."

Musician Harry Belafonte was an ardent civil rights and environmental activist. (Photo: Thomas Altfather Good, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

DYKSTRA: I promise I won't sing "Day-O" for you, but it's kind of sad that Harry Belafonte's lifetime of performing and his lifetime of activism have been condensed into that "Day-O" song, whose two words sung at ballparks all over the world. Harry was 96. President Obama said of him, "He lived a good life, transforming the arts while also standing up for civil rights. And among those rights, Harry Belafonte also stood up for environmental justice.

And Doris Bradshaw died at age 68. She was one of the strongest voices in America on environmental justice from her community in Memphis. She led protests against the siting of toxic waste facilities in poor and African American communities around the country.

O'NEILL: And Peter, sometimes we've talked about horrific consequences that come from people who stand up for environmental justice. In the past, we've talked about indigenous leaders who've been murdered for trying to protect their home.

Quinto Inuma was a prominent Kichwa leader who fought against logging operations, land trafficking, and other environmental threats in his community. (Photo: Vicki Brown, Forest Peoples Programme)

DYKSTRA: That's right, and one of the many who died in the past year is Quinto Inuma, the Peruvian activist and indigenous leader. He was killed for trying to protect the Amazon rainforest from logging around their community. We don't know how many indigenous and developing nations activists died in 2023. There are so many, sometimes over 100 in a given year, but that authoritative list won't be finalized for months.

O'NEILL: And Peter, we've talked a lot about art and activism. How about politics?

California Senator Dianne Feinstein (D) helped create Death Valley National Park and championed many environmental causes. (Photo: Senate Democrats, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DYKSTRA: There are two strong women leaders of the Democratic Party. Senator Dianne Feinstein was 90 when she passed away a few months ago. She helped create the Death Valley National Park and supported all manner of environmental measures. Congresswoman Pat Schroeder was 82. She was big on Western forest protection and the protection of water sources throughout the West. Turning to environmental journalists, my friend JoAnn Valenti was 78 years old when she passed. JoAnn's career included stints as a reporter, a journalist and professor, a publisher of environmental journalism textbooks, and a longtime member of SEJ, the Society of Environmental Journalists.

Colorado Congresswoman Pat Schroeder (D) helped protect water sources throughout the West. (Photo: marciaphotog, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

O'NEILL: And Peter, I believe you had one more activist, this time from somewhere in South Asia?

DYKSTRA: Right, in India, Aditya, nicknamed "Dicky" Singh. He was a nature photographer who became a wildlife and forests advocate, calling for reforestation of some of the many areas in his homeland that have been damaged and deforested over the years.

Wildlife photographer and conservationist Aditya “Dicky” Singh advocated for the protection of wildlife and reforestation in India. He frequently photographed tigers in northern India’s Ranthambore National Park. (Photo: Julian Mason, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

“Earthrise” gave humans their first glimpse of Earth from space. Frank Borman commanded the crew responsible for the photograph, Apollo 8. (Photo: NASA, Archive.org)

And finally, we turn to Frank Borman, died at age 95 this year. He commanded the Apollo 8 crew that took Earth's first portrait. Their "Earthrise" photographs helped millions of Earth-bound humans realize that we're all in it together.

O'NEILL: More than a half century later, that photo is still I think one of the most iconic photos of Earth.

DYKSTRA: It is indeed.

O'NEILL: Well, thank you, Peter, for helping us remember these men and women who have had such an impact on our environment. Peter Dykstra is our Living on Earth contributor from Atlanta, Georgia, and we'll talk to you again really soon.

Frank Borman suits up for Apollo 8 on launch day, December 21, 1968. (Photo: NASA, Archive.org)

DYKSTRA: Aynsley, thanks a lot, and we'll talk to you soon.

O'NEILL: And there's more on these stories and these people on Living on Earth webpage, that's loe.org.

Related links:

- Learn more about Roger Payne

- Learn more about David Crosby

- Learn more about Jimmy Buffett

- Learn more about Harry Belafonte

- Learn more about Doris Bradshaw

- Learn more about Quinto Inuma

- Learn more about Dianne Feinstein

- Learn more about Pat Shroeder

- Learn more about JoAnn Valenti

- Learn more about Aditya “Dicky” Singh

- Learn more about Frank Borman

[MUSIC: Jimmy Buffett, “Defying Gravity”, on Havana Daydreamin’, MCA Records Inc.]

CURWOOD: Just ahead, the climate emergency is getting worse, but scientists say all is not lost… yet. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Matthias Trapp, “Peaberry” Single, Chill Palm]

Our Fragile Moment

Michael Mann is a world-renowned climate scientist and a Presidential Distinguished Professor at the University of Pennsylvania. (Photo: Eric Sucar, Courtesy of Michael Mann)

O’NEILL: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Aynsley O’Neill

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Once the figures for December are officially tabulated, 2023 is likely to set the record as the hottest year ever seen by humans, topping the previous record for global average temperature readings set in 2016. And thanks to the current El Niño weather phenomenon, 2024 could be even hotter. But we still have a chance to rein in global warming before it runs too hot for our civilization, says UPenn’s Michael Mann. He makes the case in his recent book called Our Fragile Moment: How Lessons from Earth’s Past Can Help Us Survive the Climate Crisis. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Professor Mann!

MANN: Thanks, Steve, always great to be with you.

CURWOOD: So your new book uses paleoclimate research and by paleoclimate, I mean, looking way back in time fact back to... what was it.. four and a half billion years ago the Earth started as to be the Earth to frame the implications of this current climate crisis. Why is that kind of research useful when facing human caused climate change?

Michael Mann’s latest book is Our Fragile Moment: How Lessons from Earth’s Past Can Help Us Survive the Climate Crisis. (Photo: Courtesy of Michael Mann)

MANN: Yeah, thanks. Well, you know, I do cover four and a half billion years in a couple hundred pages, which is a challenge. But I do try to draw upon some key events along the way that really do inform our understanding of climate change past natural changes in climate that tell us something about the climate system, and really allows us, for example, to evaluate the models that we use to predict future changes in climate from human activity. It allows us to sort of assess how reliable those models are. It provides some constraints on those models. It allows us to look at past rapid events that might be analogues for what's happening today. And it also allows us to address some of the past events that are sometimes pointed to by what I call the climate doomers — those who insist it's too late to act on the climate crisis. And there are times when they will point to the paleoclimate record and past extinction events as evidence of that. And so I felt it was important to really review the evidence objectively and talk about that. Are we doomed? And what we see when we review the collective evidence is we're not doomed. Our fate is still in our hands. That may not be true, if we continue headlong on this course that we're on of increased extraction of fossil fuels and warming of the planet. But there is still time. And so in my review of paleoclimate of Earth history of billions of years of Earth history is a message of both urgency and agency, as I like to say.

Michael Mann hopes that sharing the latest paleo history research will give the public a better sense of the nature of the climate crisis and what we can do about it. (Photo: Robert Mace, Courtesy of Michael Mann)

CURWOOD: There's an interesting section in your book where you allude to some research, looking back to the beginning of agriculture, and how, you know, given the wobble as the Earth spins on its axis, so we should have been descending into an ice age six or 7000 years ago, things stayed warm, stayed as warm because of, say, the methane from rice production, and maybe the cutting of trees as well. How fair is it to say that a little goes a long way in terms of affecting this sort of Goldilocks climate that civilization has been able to thrive in?

MANN: Yeah, Bill Ruddiman was a former colleague of mine back when I was at the University of Virginia and formulated back then what's now known as the early Anthropocene hypothesis. We sort of created our own geological period. Now, human beings are such a large impact on the planet, that it rivals, you know, all of the other factors that drive changes in the Earth system. And so we can argue there's a whole new geological epoch that has to be defined for the period during which humans have had such an outsized impact on the environment. And we tend to equate that with the Industrial Revolution, which is when CO2 levels really ramped up. But what Bill pointed out was that you can actually go back 1000s of years, and his argument, and it's not without controversy, and there are scientists who disagree with the hypothesis. But I think he's made an interesting and solid case here, that these long term natural drivers that drive the coming and going of ice ages over many 1000s of years, were actually slowly leading us into the next Ice Age ever so slowly, the planet should have been cooling. And yet it didn't cool.

Prof. Mann spreads a message of “urgency and agency” when it comes to addressing the climate crisis. (Photo: Amanda Mustard, Courtesy of Michael Mann)

Global temperatures remained remarkably flat. He argues that that's because already through rice cultivation, deforestation, and other activities, human beings were impacting the climate, very moderately, just enough to offset a very small natural cooling trend that would have occurred. And so it really is an example a little bit of a good thing, a little bit of impact on the climate, actually kept global temperatures, as stable as they were. The problem is we got more and more efficient at impacting the climate. We started burning fossil fuels, oil, natural gas, and coal. And pretty soon we're having not a modest small impact on the Earth system, but a massive impact. And that's where we are today.

CURWOOD: Now, your book both highlights the degree of the crisis, but also dispels some apocalyptic myths about where we're headed right now. For example, you explain why runaway climate change is not inevitable, because of say a methane bomb. And by the way, what is a so called methane bomb and why is it unlikely to occur and lead to runaway climate change? I mean, I believe you mentioned methane bombs as part of the paleoclimate history.

According to Prof. Mann, solving the climate crisis depends on a thriving American democracy and American leadership. (Photo: Bill Clark/CQ Roll Call file photo, Courtesy of Michael Mann)

MANN: You know, a lot of the sort of doomism that you hear today, this idea that it's too late to even act on climate because we have, you know, unleashed runaway warming that will lead to our extinction no matter what we do. And there is a pretty large movement, so called deep adaptation, you know, a movement that has widespread appeal to a fairly large number of people out there been taken in by this sort of narrative that, you know, we now just have to find a way to adapt to this harsh new existence, because there's nothing that we can do to stop it. And the argument is premised on the notion that, for example, we have unleashed methane from the permafrost of the Arctic, the warming of the Arctic has caused the release of methane, a very potent greenhouse gas, it can potentially push us across certain thresholds. The idea is that we've released massive amounts of methane that are going to push us beyond catastrophic thresholds. And it's unstoppable because the warming is in place. It's a runaway we call feedback mechanism, and we can't stop it. And that notion is often premised on the idea that we know that's happening today because it's what happened in the past with past extinction events. The sort of doomers out there will point to, for example, a period known as the Paleocene Eocene Thermal Maximum just rolls off the tongue, the PTM, as we call it. Fifty-six-million years ago, there was a fairly abrupt natural warming event. And it did lead to all sorts of consequences, extinction of many species.

Climate “doomers” frequently say that, due to humanity’s release of methane (a potent greenhouse gas modeled here), there is nothing to be done to minimize the climate crisis because we’ve initiated an unstoppable feedback loop. Prof. Michael Mann believes that the paleoclimate record indicates that this is not the case. (Photo: Christine L. Miller, Courtesy of Michael Mann)

The doomers will argue that it was caused by the same sort of release of methane, the unstoppable release of methane that's happening today. And so I spent quite a bit of time unpacking what the evidence actually says about the PTM, looking at it in some detail. And the best available science now suggests that methane at most was a very small player. The main factor was the release of carbon dioxide, in this case, a natural release of carbon dioxide over 1000s of years from an unusually active period of volcanism, in fact, volcanoes located in the vicinity of Iceland that just pumped huge amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere over 1000s of years. And so the lesson here was the massive warming was caused by the release of the very same greenhouse gas, carbon dioxide, that we are releasing today through unnatural activities, the burning of fossil fuels, and we can do something about it. We can stop the generation of this carbon dioxide and the continued warming of the planet. So the real lesson here is about the agency that we still have in preventing catastrophic warming.

CURWOOD: So the Biden administration issued the Fifth National Climate Assessment in the fall, how does that assessment stack up? I mean, where is it strong? And from your perspective, not so strong? What more should it do? And what did it do well?

MANN: Yeah, I think the report is a good summary of the mainstream scientific understanding. You know, it's sort of driven by the climate models that we have today, much of the, you know, the predictions are really based on climate models. Some of our own work suggests that there are certain types of extreme weather events, for example, that aren't really being very well captured by the climate models. And it has to do with subtle sort of the subtle physics of the behavior of the Jetstream when you warm up the planet, that are difficult to capture in the still somewhat coarse resolution global models that we use. So I've argued that you know, these models are probably underestimating the impact that climate change is already having on these very destabilizing extreme weather events. It's really where the rubber hits the road is with these extreme events, the wildfires and floods and heat waves and droughts, superstorms. The models may be underestimating the dynamic nature of the ice sheets. The ice sheets might not be quite as stable as the climate models envision them as being, which means we could see more rapid disintegration and faster sea level rise. Uncertainty, as I like to say, is not our friend. And so while the report does a good job summarizing the mainstream scientific understanding, that understanding is substantially driven by the models we have and those models aren't perfect. Uncertainly isn't our friend. The models may be underestimating some of the threats that we face.

COP28, the annual U.N. climate conference, concluded in December 2023. While there was promising progress, many climate advocates say it’s not enough. (Photo: International Labour Organization, Courtesy of Michael Mann)

CURWOOD: Sounds to me like you're not exactly thrilled with some of the predictions that the National Climate Assessment makes regarding extreme weather events, and sea level rise and that sort of thing.

MANN: I think these reports tend to be conservative because they stick pretty close to like what can be justified based on the state of the art climate models. I certainly wouldn't fault my colleagues. And I would point to some of the successes at the same time. The models have done a remarkably good job in predicting the overall warming of the planet. People love to poopoo the models. But in fact, if you look at early predictions of warming, those predictions have been right on target. So if you feed them the increase in carbon dioxide, that has actually resulted from the decisions we've made, or the decisions we haven't made to curtail fossil fuel burning, the models warm up almost exactly the right amount. Where they tend to go wrong is in some of the more subtle consequences of that warming, the complicated dynamics of the ice sheets. They're difficult to model in this context accurately. There are processes that we know occur in nature that we're still having trouble representing accurately in the models. Same thing with extreme weather events, subtle features, the Jetstream that are difficult to capture in some of these models. And so the lesson is, it's sort of a mixed picture. They've predicted the overall warming of the planet quite well. And that's important, because so many consequences are related to that. But some of the impacts have probably been under predicted. And the assessments have to be based in part on guidance from the models that we have. And to the extent that those models are overly conservative with respect to some of the consequences, those assessment reports, the IPCC assessments and the National Assessment Report of the United States are going to under state some of those potential consequences.

Some paleoclimate scientists hypothesize that human activities such as rice farming warmed the planet, preventing an ice age. This is referred to as the “Early Anthropocene” since it occurred before the Industrial Revolution and the climate crisis. (Photo: Marie Anna Lee, Courtesy of Michael Mann)

CURWOOD: So Professor Mann, we're putting you on the air at the beginning of 2024, to give us some hope, going forward for this next year, in the aftermath of a Conference of the Parties at the UN summit, that some people found less than satisfactory. So it's interesting, though, because COP28, some people say, well, there was progress made, and other people say, but that progress is totally insufficient to what needs to be done. And in a way your book says, "Well, if we are kind of in the middle, and doing something, things may not turn out so bad. It may not be a totally existential threat to our civilization." How fair is that?

MANN: Yeah, you know, right now, we haven't yet seen the progress necessary to limit warming to 1.5 Celsius. It's a little under three degrees Fahrenheit, if you do the translation. That amount of warming of the planet will be deeply problematic, not civilization ending, but if we exceed that amount of warming, there's going to be that much more damage that much more mortality and harm than we've already seen. And we will start to see the erosion of our adaptive capacity, especially those in the Global South, who are facing some of the worst consequences of climate change already. So we are sort of in that in between area where we're seeing progress, perhaps enough progress to prevent what we might think of as sort of civilization ending climate change, but not enough progress to avert great amounts of damage and harm. That's where we are. And that window of opportunity to limit warming, again, below 1.5 Celsius, we're at 1.2 Celsius, we want to keep it below 1.5 Celsius, to avert some of the worst consequences, that's not a lot of wiggle room. And that window of opportunity to decarbonize our civilization fast enough to avert that amount of warming is closing with each COP. With each Conference of the Parties, where we don't see a substantial ratcheting up of the commitments from the various countries of the world. That window gets shorter and shorter, gets smaller and smaller. And that's where we are right now.

CURWOOD: So, Michael Mann before you go, your book, Our Fragile Moment, ends with a message that while the situation is in a perilous state, there is still time to change course. So as 2024 begins, what do you think the next steps are for the United States? And what do you hope from the rest of the world as well?

MANN: I don't think there's any path to meaningful global climate action where the United States fails to lead. We are the world's largest cumulative carbon emitter. China may be emitting more carbon right now, but we've put more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere than any other country. And, in the end, that's what the climate system cares about. It cares about the accumulation of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. That means we have, you know, the greatest responsibility to take leadership. And when the United States does lead, we've seen that other countries like China tend to come to the table. So U.S. leadership is critical. There is no possibility of U.S. leadership on climate if we fail to preserve democratic governance in this country. Our democracy is on the line in this next election. And people need to think about that, because if we fail to preserve our democratic institutions, it's very difficult to see how we act when it comes to the crises we face like the climate crisis.

CURWOOD: Michael Mann's book is called Our Fragile Moment: How Lessons from Earth's Past Can Help Us Survive the Climate Crisis. Thank you so much, Professor.

MANN: Thank you, Steve. Always a pleasure.

Related links:

- About Prof. Michael Mann

- Explore Michael Mann’s other work

- Learn more about COP28

- Watch videos about paleohistory

[MUSIC: Rikard From, “Let Me Take You for a Walk” on Sun Of June, Rikard From Records]

O’NEILL: Next time on the show, we all have a role to play in addressing the climate emergency to help save life as we know it. But it’s a different story when it comes to who’s responsible.

ORESKES: We know from our research and the research of others that as early as the 1960s, the oil industry was quite well aware that burning fossil fuels put greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, and those gases were almost certain to warm the planet. And they also knew that the effects would likely be very serious. We begin to see really serious, sustained work on issue in the 1970s. And by the mid to late 70s, some companies like ExxonMobil actually had their own in house scientists doing this research. And so we've shown in our work, we've gone back and we've looked at those reports, we've looked at the scientific papers that were published, either by industry scientists or co-authored by them with academics, and they show very clearly that by the late 70s, early 80s, the oil industry had a very clear picture of what this problem was understood that it was serious that it would have large social, economic and political consequences, that it could include very substantive sea level rise, and that it might make their product unsellable.

O’NEILL: That’s next time on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Rikard From, “Let Me Take You for a Walk” on Sun Of June, Rikard From Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Josh Croom, Jenni Doering, Swayam Gagneja, Mattie Hibbs, Mazzi Ingram, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Sarah Mahaney, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari.

O’NEILL: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments at loe dot org. I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth