January 26, 2024

Air Date: January 26, 2024

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

SCOTUS Could Strip Agency Power

View the page for this story

Two cases in front of the Supreme Court are looking to restrict federal agency power by overturning the longstanding Chevron Doctrine. Pat Parenteau, emeritus Professor at Vermont Law School, joins Host Aynsley O’Neill to explain how this could limit the ability of federal agencies to set strong environment and climate regulations. (12:35)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Living on Earth Contributor Peter Dykstra joins Host Aynsley O’Neill to share research that found a positive link between kids’ access to green space and their bone density. They also talk about how the practice of “deconstructing” buildings instead of demolishing them allows for reuse of many materials. And in history, they remember Pete Seeger, who passed away ten years ago after a lifetime of contributions to environmental causes and, of course, folk music. (04:40)

The New Climate Denial

View the page for this story

A recent report finds that social media platforms like YouTube are amplifying and sometimes profiting from new forms of climate denial that falsely claim it’s too late to act on the climate crisis. Imran Ahmed is the CEO and founder of the Center for Countering Digital Hate and joins Host Steve Curwood to talk about how climate disinformation has evolved from attacking science to attacking solutions. (13:44)

In Defense of Little Foxes

View the page for this story

Living on Earth Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender, describes his internal conflict when a red fox who’s a welcome visitor to his backyard pursues a familiar squirrel. (02:36)

"Phoenix" Trees Rise from the Ashes

View the page for this story

Nearly all the tall coast redwoods in California’s Big Basin Redwoods State Park burned in a 2020 wildfire. But within a few months, the charred trunks had grown a fuzz of healthy green shoots. A new paper documents how the trees were able to regenerate using energy reserves stored for many decades. Lead author Drew Peltier teaches at the University of Nevada – Las Vegas and joins Host Jenni Doering to explain the science behind this stunning recovery. (12:32)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

240126 Transcript

HOSTS: Jenni Doering, Aynsley O’Neill

GUESTS: Imran Ahmed, Pat Parenteau, Drew Peltier

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Mark Seth Lender

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

DOERING: I’m Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill. Two cases in front of the Supreme Court are looking to restrict federal agency power.

PARENTEAU: The pattern here is crystal clear. No environmental regulation that comes before this court is going to emerge unscathed. This court seems to be on a mission to roll back federal regulation.

DOERING: Also, after a fire burned 97% of a redwood forest, the trees survived thanks to stored energy.

PELTIER: Some of these carbon reserves were on order of 50 to 100 years old. What that means is that carbon that was photosynthesized in the atmosphere potentially back in the 1940s is being used to regrow new leaves now after fire.

DOERING: And we’ll continue our climate disinformation series this week on Living on Earth. Stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

SCOTUS Could Strip Agency Power

If the Supreme Court were to overturn the forty-year-old Chevron doctrine, it could allow for a reduction in the power of federal agencies like the EPA. (Photo: Thomas Hawk, Flickr, CC BY NC 2.0)

DOERING: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill. The majority conservative Supreme Court made waves in 2022 when it overturned Roe v. Wade, throwing out a legal precedent that had protected reproductive rights for nearly fifty years. And the Court has signaled its interest in reversing other established precedents, including one that could bring major consequences for climate and environment. On January 17, two cases were heard in the Supreme Court, both of which proposed overturning the longstanding Chevron doctrine. The country’s highest court had adopted it back in the 1984 case, Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council. Pat Parenteau is an emeritus professor at Vermont Law School, and he says the doctrine has guided federal regulatory law for decades.

Challengers of the Chevron doctrine like Associate Justice Neil Gorsuch say federal agencies have too much power. (Photo: Franz Jantzen, Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

PARENTEAU: The Chevron doctrine basically says, when Congress writes laws that have some ambiguous terms, in other words, terms that are vague and not precise enough, that agencies like EPA that are interpreting those statutes have some discretion. And as long as their interpretation is reasonable, the Chevron doctrine says courts must defer to the agency's interpretation. And that has been the law for 40 years. And it has been the source of considerable agency authority to deal with problems that Congress did not, and frankly could not, have anticipated many years ago when these laws were originally enacted. If you think about air pollution, water pollution, climate disruption, you know, all of these things have come into focus over the years. And the statutes that were written in the 1970s don't always anticipate those. So the doctrine has been a bulwark of environmental protection for 40 years, and it's now on the line in the Supreme Court.

O'NEILL: So this doctrine has been instrumental in upholding a range of environmental protection rules. But from what I understand, environmentalists were not exactly thrilled about the Chevron doctrine when it was first adopted. Why was that?

PARENTEAU: Well, because it cuts both ways. You see, if an agency, let's take, for example, the prior administration under Trump, that was rolling back environmental protections across the board, you see, that doctrine also applies to agencies that are undercutting or weakening environmental protections. And environmental groups have lost a number of cases, because the courts deferred to an agency's interpretation, even though the interpretation was not as protective of public health and the environment as it might otherwise have been.

O'NEILL: Talk to me about these two cases that the Supreme Court heard. What's going on that's bringing it back up now? What are the arguments for overturning a 40-year-old doctrine?

In the two cases brought to the Court, the offshore fishing industry objects to NOAA’s mandate that vessel owners pay for federal monitors on board. (Photo: Lochaven, Flickr, CC BY NC ND 2.0)

PARENTEAU: Right. Well, the cases themselves are surprising because they deal with so little. They both involve the requirement in the offshore fishing industry to have monitors on the boats to make sure that fishing boats are not exceeding their catch quotas, because overfishing is a major problem. So the controversy here is over who has to pay for having these monitors on board. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration adopted a rule saying the vessel owners must pay for these monitors. That's what the fishing industry is objecting to. And the statute involved doesn't speak directly to this question of who pays for the monitors. And that's the narrow legal question that's presented in the case. But you see, it's a very, what I would characterize as a "small potatoes" kind of problem. And yet, it's one that the Supreme Court has decided to use as a vehicle to reevaluate the Chevron doctrine. We know that several justices, led primarily by Justice Gorsuch, have had their eye on overturning the Chevron doctrine for many years. They've written about it. Gorsuch has filed dissenting opinions in cases saying we should directly address this and overrule Chevron. So the conservative justices have been waiting for an opportunity to decide once and for all whether the Chevron doctrine will remain as it has for 40 years, or perhaps whether some form of it will remain, albeit one that's significantly modified.

O'NEILL: And Pat, can you explain to me the why somebody would want to overturn this Chevron doctrine? What would be the consequences if it were to be thrown out?

PARENTEAU: Well, I think the industry critics and challengers believe that the agencies are overreaching, and that isn't just the industry. That's a lot of Republican state attorneys general. They're the ones that have been leading the charge against federal authority and particularly environmental regulations. So there's a feeling out there, among what I would say, anti-regulatory forces, that without Chevron, they'll be more successful in challenging, for example, EPA, but other agencies. In this case it’s NOAA, you know, protecting marine mammals and fish, but it could be the Department of Interior protecting endangered species, a number of different agencies that have come under fire. And getting rid of Chevron, these opponents of federal regulation believe, will make it harder for these agencies to restrict activities that people don't want to have restricted.

Main entrance of U.S. EPA Headquarters; the William Jefferson Clinton Federal Building on 12th Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. The Chevron Doctrine says courts should defer to the expertise of federal agencies like the EPA when legal language is ambiguous. (Photo: EPA, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

O'NEILL: So we've seen the conservative Court take down some pretty foundational environmental protections over the last year. We always talk about Sackett versus EPA, which seriously endangered wetland protections in the country. To what extent do you think the Court is likely to continue that trend of chipping away at environmental protection?

PARENTEAU: Yeah, there's no indication that this Court has changed its attitude or view, the majority of the Court, towards not just environmental regulation—I think the bigger picture here is that this Court simply believes agencies across the board have gone too far, that they're asserting authority that only the legislative branch should assert. It's not clear that they're correct, that these burdens that are being imposed by regulation are unjustified. In fact, study after study shows that they are economically justified, that by protecting public health, you have less medical costs, you have less lost time from jobs, you have cleaner air, cleaner water, less cost of treatment for pollution, etcetera. But nevertheless, it's pretty clear that the conservative justices do adopt that worldview, that agencies have too much power. And they are going to cut back on that when they get cases before them like these two cases that are pending today. Like the West Virginia case where they struck down EPA's authority to regulate greenhouse gases from power plants, like the Sackett case you mentioned, where the Court for the first time dramatically reduced protection for wetlands and streams all across the United States. The pattern here is crystal clear: no environmental regulation that comes before this Court is going to emerge unscathed. It may not even emerge still functional. This Court seems to be on a mission to roll back federal regulation.

O'NEILL: And, Pat, if this Chevron doctrine gets thrown out, what would be replacing it?

After environmental advocacy groups sued Shell over the excess emissions produced by the ethane cracker plant in Beaver County PA (pictured above) Shell agreed to pay $10 million to the state. Overturning the Chevron doctrine could weaken agencies’ ability to regulate industry when it comes to pollution, species loss, and public health. (Photo: Mark Dixon, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

PARENTEAU: There's another doctrine that we lawyers call Skidmore. And this doctrine basically says, agency interpretations of vague or ambiguous statutes will be given the deference they deserve. In other words, it's what Justice Kavanaugh called, “the power to persuade, not the power to control.” What that means is, if an agency's articulation of its reasons for taking the action it's taking are convincing enough to the courts, then their interpretation will be given some weight. It simply won't be controlling in the way that the Chevron doctrine has required, right? And so what that means practically, think about this for a minute. There are 800 federal judges in the United States right now. If you've removed a rule which is pretty straightforward, if the agency's interpretation is reasonable, you'll have to accept it, and they're going to replace that with individual judges deciding for themselves what these words mean—maybe they'll give the agency some deference or some weight, maybe they won't. Think about the chaos that could create. And if you think about who has appointed many of these judges, former President Trump has appointed over 300 federal judges, of course, including three Supreme Court judges. So I think it's not too hard to say you're going to see a lot of conflict in the lower courts as a result of this decision, because the people that are challenging Chevron aren't going to be satisfied once they do away with the doctrine. They're immediately going to be challenging each and every rule that comes down the pike. And there are many in the pipeline right now with the Biden administration trying to correct what the Trump administration had done.

Pat Parenteau is emeritus professor of law at Vermont Law School and formerly served as EPA Regional Counsel. (Photo: Courtesy of Vermont Law and Graduate School)

O'NEILL: So how is this decision going to affect pending cases that are right now trying to challenge the Biden administration's environmental agenda?

PARENTEAU: Right, well, there's a raft of them. The Biden administration is having to replace the old Clean Power Plan that regulates greenhouse gas emissions from power plants. That's in the final stages of being adopted. We know that's going to be challenged. So that's one. Another one is the methane rule, which regulates methane emissions from the oil and gas industry—that’s being challenged. Another one is yet another Clean Water Act rule, which gives states the authority to veto federal permits and licenses for pipelines and other infrastructure where it's damaging or potentially damaging water quality, beneficial uses of water wetlands and so forth. The Endangered Species Act rule that the Department of Interior is adopting to correct what the Trump administration tried to do. All of these rules are in litigation or about to be in litigation. So all of these different cases are going to involve controversial interpretations that could go one way or the other. And if you're just going to leave it to individual judges to make that decision, we're surely going to see inconsistencies, conflict, and uncertainty going forward.

O'NEILL: Pat Parenteau is an emeritus professor of law at Vermont Law School. Pat, as always, thank you so much for your time today.

PARENTEAU: Thanks, Aynsley. It's always good to be with you.

Related links:

- Inside Climate News | “Supreme Court Weighs Overturning Chevron Doctrine”

- SCOTUSblog | “Supreme Court Likely to Discard Chevron”

- Harvard Gazette | “‘Chevron Deference’ Faces Existential Test”

[MUSIC: Greg Brown, “Poet Game” on In the Hills of California, by Greg Brown, Red House Records]

DOERING: Coming up, there’s a new kind of climate denial in town. That’s just ahead. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green, and protect the seas they love. More information at sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: The Marcus Roberts Trio, “Nothin’ Like It” on In Honor Of Duke, Sony BMG Music Entertainment]

Beyond the Headlines

A study in the journal JAMA Network has linked increased bone density in children to the amount of green space near their homes. (Photo: Lee Simpson, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

O'NEILL: And I'm Aynsley O'Neill. It's just about the time in our show where we take a look beyond the headlines with our Living on Earth contributor, Peter Dykstra. He should be joining us now from Atlanta, Georgia. Hi, Peter, what's going on out there in the world that didn't quite make it to the headlines yet?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Aynsley. Didn't quite make it to the headlines, but a couple interesting stories that may yield positive results. The first one is a study from Belgium. It was published in the journal JAMA Network Open. Three hundred children were study subjects, ages four to six in the Flanders region of Belgium. Urban, suburban, and rural areas were included. And these kids showed much greater bone density if they lived in areas where green space, natural areas, were nearby.

O'NEILL: All right, well, green space areas sound pretty good to me. But what does the increased bone density mean for the kids?

DYKSTRA: It means a lot. It accelerates growth and the development of those kids' bodies as they move toward adulthood. But it also means a lot further down the road. Bone density as we age is a very important factor in preventing problems like osteoporosis. This Belgian study says that kids have a much lower risk of that low bone density, and their development can be much stronger at a younger age.

O'NEILL: All right, well, we'll add that to the list of great reasons to have green spaces near your home. What else do you have for us, Peter?

Deconstruction is the process of dismantling a building so that its materials can be reused. Here, the Deutsche Bank building in New York City underwent deconstruction in January 2008. (Photo: ProhibitOnions, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

DYKSTRA: Another one that's an experiment that may already be paying off benefits in US cities like Portland, Oregon and San Antonio. Those cities are working to keep building materials out of landfills. Deconstruction is the name for it. We tend to look at buildings as something that we put up and when their useful lives end, we simply throw them away at a demolition site. 150 million tons of debris makes it to landfills and dumps across the US. Globally, the problem is much bigger than that.

O'NEILL: But so what is deconstruction, Peter? Is it just to save us the difficulty of trotting a wrecking ball out there?

DYKSTRA: It could be as simple as reusing wood from older buildings in order to build anything from flooring to a mantelpiece for a fireplace, but it could also involve grinding down old concrete and turning it into newer concrete. Concrete is essentially sand and glue. So when you think about it, it's not that hard to recycle and reuse again the basic elements of concrete.

O’NEILL: Reducing the new and reusing the old, that's a good step towards sustainability when the world is only getting more urbanized. And now Peter, I would like you to take me back into history and tell us what went on there.

Pete Seeger died in 2014, leaving behind a musical legacy as well as a history of environmental activism. (Photo: Donna Lou Morgan, U.S. Navy, Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

DYKSTRA: January 27, 2014, only 10 years ago, the beloved musician and activist Pete Seeger passed away at age 94. Seeger was blacklisted during the McCarthy era in the Cold War, and later he was voted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, a pretty unique honor for a folk singer. He steered much of his good-natured zeal toward cleaning up the Hudson River. He launched the sloop, "Clearwater" as an educational and political floating symbol. Then he was instrumental in founding the first "Riverkeeper" on the Hudson. There are now hundreds of "Riverkeeper, "Baykeeper," "Soundkeeper," "Harborkeepers" throughout the world. Seeger helped start the first. His life and legacy go beyond the music, and all the way toward cleaning up one of the world's great rivers.

O'NEILL: Yeah, and I know he spoke about his environmental activism with our executive producer, Steve Curwood, back in 1998. We'll always remember Pete Seeger fondly here at Living on Earth.

DYKSTRA: We will indeed.

O'NEILL: All right, Peter. Thank you for bringing us these stories, as always. Peter Dykstra is a Living on Earth contributor, and we will talk to you again really soon.

DYKSTRA: Ok, Aynsley. Thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

O'NEILL: And there's more on these stories, including a link to that afternoon with Pete Seeger, on the Living on Earth website. That's loe.org.

Related links:

- The Guardian | “Children Living Near Green Spaces ‘Have Stronger Bones’”

- Read the JAMA Network article here

- Grist | “To Keep Building Materials Out of Landfills, Cities Are Embracing ‘Deconstruction’”

- Find Living on Earth’s “An Afternoon with Pete Seeger” here

[MUSIC: Lex Von Sumayo, “Turn! Turn! Turn!” on YouTube/lexvonsumayo@gmail.com, Music by Pete Seeger/arr. by Lex Von Sumayo-Words from The Book of Ecclesiastes]

The New Climate Denial

Social media platforms are making it easier than ever to promote climate disinformation. (Photo: Oleksandr P., Pexels)

DOERING: We continue our series on climate change disinformation with a look at how climate denial has evolved in just the last few years. Climate science has been under attack for decades. But some climate deniers are no longer refuting the fact that the Earth is warming because of human activity. Now their message focuses on doom. They admit our planet is running a fever, but shrug and say there’s not much we can do about it. A new report from the Center for Countering Digital Hate takes a close look at this new form of climate denial and how it shows up in videos on one of the internet’s most popular content sharing platforms, YouTube. And when ads run on those videos, the climate deniers and YouTube often pocket the profits. Imran Ahmed is the CEO and founder of the Center for Countering Digital Hate, and he joined Living on Earth host Steve Curwood to share the findings.

CURWOOD: So how long did you work on this study looking at how social media is, in some cases, maybe many cases, promoting disinformation about climate change?

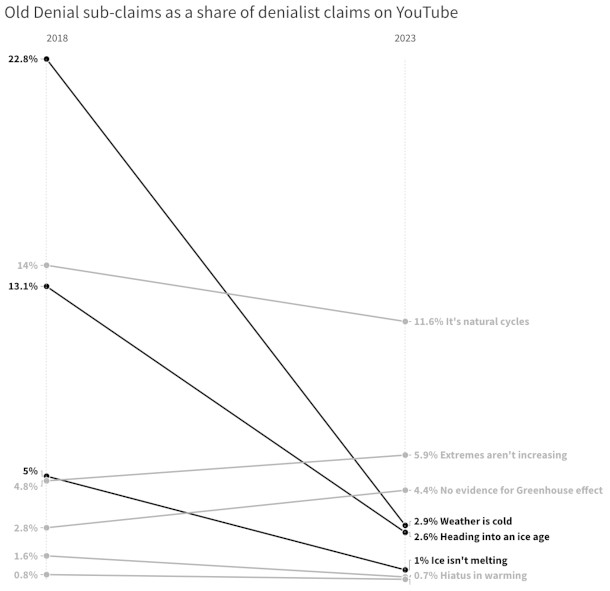

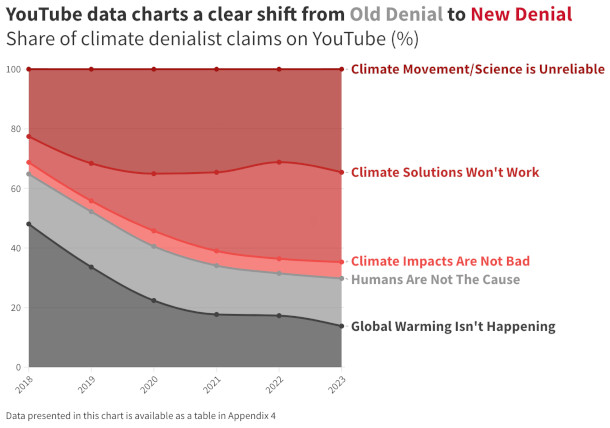

AHMED: Well, this has actually been one of the longest and most complex studies we've ever done. We had to work with university researchers who have developed an AI model that allows them to identify, to actually schematize and work out what type of climate denial claim is being made in this piece of text. What we used that tool to do was analyze thousands of hours of YouTube videos produced by prominent climate deniers and study the evolution of the types of claims they've been making between 2018 and 2023. And what we saw was startling: a real collapse in the volume of claims being made that anthropogenic, so manmade climate change, is not happening, that either it's not happening at all or that it's not manmade, and an explosion in the volume of claims that, you know what, climate change may be happening, but the solutions don't work. So climate deniers have transitioned from the old climate denial, which is rejecting anthropogenic climate change, to a new climate denial, which is casting doubt on solutions.

CURWOOD: So talk to me more about this question of old denial and new denialism. Your report says that climate denial folks have moved beyond trying to say that climate change isn't happening and humans aren't related to this. But moving into the area that the solutions won't work, why is that new? Because from day one, people opposed to climate action said, oh, it costs too much, that won't work, the technology is too expensive, and you know, we're gambling way too much on "iffy" technology. What's new about the kind of, what you call new denial?

Imran Ahmed is the CEO and founder of the Center for Countering Digital Hate. (Photo: Courtesy of CCDH, Imran Ahmed)

AHMED: So it's really the focus that we're looking at here. As solutions have developed to become more sophisticated, as the world has become more convinced of the dangers of climate change, as political actors and as companies and as others have taken action, what you have seen is the battleground shifting. And so in 2018, over two thirds of all the claims made were rejecting the reality, the scientific consensus, on climate change. Now, that's less than three in 10. So less than a third. And what is now two thirds of all claims made is these other forms of denial. The three major families in the new denial are: that climate solutions won't work, that the impacts of global warming are beneficial or harmless, or that the climate science and the climate movement are unreliable. Because let's be absolutely frank about this. This has never been a debate about the science. This has been a debate between scientists and those who want to stop action being taken on climate change because that would destroy the oil and gas industry. And they are implacably opposed to climate solutions being put in place. They don't care whether it is by persuading people that climate change isn't real, or even more cynically, by dashing their hope that climate change can be dealt with.

CURWOOD: So how do they sell this notion that nothing can be done about climate through social media? How do they tell that story?

AHMED: You know, one of the things that you learn after studying disinformation and conspiracy theories and this kind of content over years and years, as my team has, not just in climate, but also public health, is that underpinning every conspiracy theory, every bit of misinformation, is fundamentally a lie. The lie is that there's nothing we can do about it. The lie is that solar power, that wind power, that tidal power, that switching to electric vehicles, couldn't substantially help to mitigate the worst ravages of climate change. But what they then claim is that well, sure, you might want to switch to an EV. But did you know that throughout the supply chain of an EV, in that creating that EV actually uses more CO2? Now, that's actually nonsense. It's been shown by the EPA and by a raft of scientists that actually the lifetime emissions of an electric vehicle is significantly lower. But what they're doing is, they're selling a lie, which is, don't buy an EV because it's worse for the environment.

“Old Denial” claims, which reject the reality of anthropogenic climate change, no longer make up the majority of denialist claims on the YouTube channels studied. (Photo: Center for Countering Digital Hate)

CURWOOD: Let's talk about how this social media works in part to appeal to a sense of "doomerism" among young people, that, yeah, well, climate's a problem, but hey, we're over the edge. So we might as well party until the asteroid or whatever hits.

AHMED: Well, I can't think of anything more cynical, can you, than telling young people that, yes, the world's climate is changing in potentially catastrophic ways, but there's no hope, and nothing that you can do could help, so may as well live with it. You know, we did some polling to go alongside this study, just to check what the acceptance levels are of different types of climate denial with young people. What we found is that acceptance of the old climate denial is incredibly low. What's been replacing it is more acceptance of the new climate denial. But you know, I think that there is a really important message here. Science won that first battle. Scientists, journalists, politicians, communicators have persuaded and explained to the public and young people that climate change is real. But the opponents of action on climate change have opened a new front. It's vital that this message is heard by the climate advocacy movement, because we're going to have to refocus our efforts, our counternarratives, our resources on explaining why climate solutions are viable, how we can save our planet and save our ecosystems.

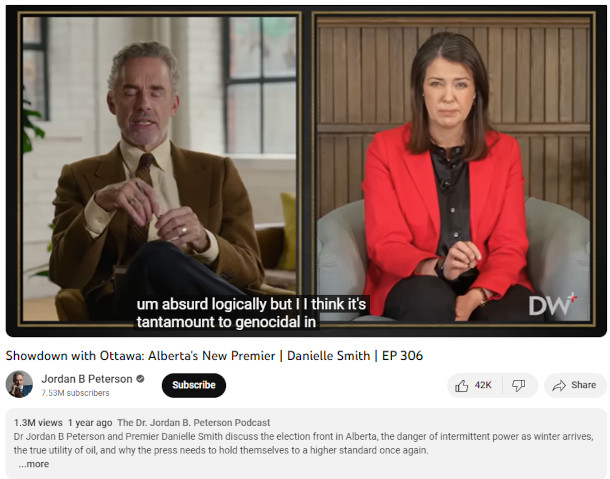

CURWOOD: So talk to me about what these videos look like, how they feel. I mean, what kind of strategies are these YouTubers using to make their information seem legit?

“New Denial” claims now dominate the YouTube channels studied. (Photo: Center for Countering Digital Hate)

AHMED: Well, they bring on experts. They have the appearance of academic or research neutrality, they have visuals, graphs. Sometimes the presenters even wear a tweed jacket to make it look as though they're erudite. It's a trick I have used in the past myself. And cherry-picked data, which is not representative of the whole. So all the tricks that you expect from shysters and snake oil salesmen. It's a toxic mélange of lies and truth that make it very difficult to discern what on earth is going on, often delivered at, you know, a fevered pace that, if you're trying to fact check it, you're overwhelmed by the next lie before you've even, you know, managed to consume or work out the truth behind the last lie. It's a sophisticated industry, and they learn from each other. They learn from other sectors. There is an enormous amount, as you will know, of disinformation around public health, around vaccines. I mean, one of the things that we always find with this is that there is an asymmetry when it comes to disinformation. You know what, it takes no effort at all, it takes no science, it takes no education, it takes no thinking to actually come up with a lie. The problem is that debunking that lie often requires effort, it requires expertise, it requires resources. And so you get this asymmetric tidal wave of disinformation, in particular on social media, because social media is the environment where bad actors can not just promulgate, can not just spread this disinformation, these lies, very easily. But also, ironically, they get amplification, and they get economic reward for it. So they get amplification because people engage with that content, often in anger, saying this is nonsense. But that actually signals to the platform, this is high engagement material, and they publish it to more and more people and more and more timelines. But second, the platforms, like YouTube in our study, place ads on this content. Those ads make money for YouTube, millions of dollars a year, in spreading disinformation about climate, but also for the producers as well, who get a take of all of that. So actually, there is this sick industry that is profiting from making people feel there is no hope on climate change.

“New denial” claims cast doubt on climate solutions and the climate movement. In this video Jordan Peterson interviews Canadian politician Danielle Smith. While in conversation he says, “In the terms that the environmentalists themselves hypothetically hold dear, the idea that we can make the planet more habitable on an environmental, on the environmental front by impoverishing poor people, by raising energy prices and food prices, is absolutely, it’s not only absurd logically, but I think it’s tantamount to genocidal.” (Image: Screenshot of Jordan Peterson video, courtesy of Center for Countering Digital Hate)

CURWOOD: So what kind of money are we talking about, with the millions of dollars of ads in social media?

AHMED: So just looking at the 100 channels that we studied, and there are thousands more, of course, but the 100 that we studied, which was 12,000 videos, 4,000 hours of content that we studied, that's worth around $13.4 million, we estimated, a year. Now that's using figures which are freely available, you know, on how much an ad costs, how often those ads appear, et cetera, et cetera. We don't know precisely what the split is, but it's about 55 to 45, 60 to 40, for the content creator and the platform. So both of them are profiting lavishly from this kind of content. What we will find, though, is that there'll be other channels around as well. So actually, these numbers are a very, very small estimate of the channels we looked at. We could be talking about $100, $200 million industry in total.

CURWOOD: Yeah, I was going to ask, did you look at the advertisements that happened on Facebook, and other social media that's out there?

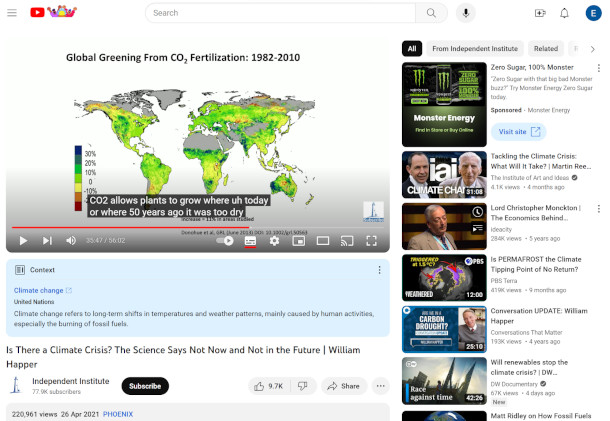

Other “new denial” claims argue that CO2 has positive effects. These screenshots show ads for Monster Energy served on and next to a video from the Independent Institute promoting the claim that CO2 has been beneficial for greening, saying: “The western United States is greening, western Australia is greening, western India is greening and this is almost certainly due to CO2. And the reason this happens is that CO2 allows plants to grow where today or where 50 years ago it was too dry.” (Image: Screenshot of Independent Institute video, courtesy of Center for Countering Digital Hate)

AHMED: You know, this initial study was based on YouTube because it's a platform that we were able to study using this tool very easily. However, we are absolutely certain that this is happening not just on Meta platforms, so on Facebook, on Instagram, on TikTok*, but also on X, which is owned by Elon Musk, a man who recently claimed that no human being on earth has done more for the planet than he has, but at the same time runs a platform that is rife with disinformation about climate, and that is helping to undermine the consensus that we need for action to be taken to mitigate climate change.

CURWOOD: What about the issue of censorship, though? I mean, everyone does have a right to free speech, not the right to shout "fire" in a crowded theater, but we have pretty strong free speech rights. Where do you think the limits should be set on this kind of information?

AHMED: Everyone has absolutely the right to hold opinions, no matter how ridiculous or counterfactual they are. People can post it if they want to. But not everyone has a constitutional right to profit from it, nor do they have a right to have a megaphone handed to them so that they can scream it to a billion people. And that's the issue here. Censorship is about the government saying that you're not allowed to say something. A private company has every right to say, I'm not gonna give you money for the content that you've just produced. That's not censorship. That's just not paying people for what they say. And so this isn't a question of censorship. This is a question of rewards. Look, in the past what YouTube has said, and this is their own rules, not my rules, their own rules, that they've said that they will not put ads on, nor will they amplify climate denial content that goes against the scientific consensus on climate change. Now, what we found was, first of all, that they're not sufficiently enforcing that policy anyway. And they responded to our study by saying, whoops, you're right, we'd better take the ads off these videos that you found. But second, we've said they should extend their policy, which only applies to the old denial, to the new denial, too. You simply cannot be calling yourself a green company, and then commit the stultifying hypocrisy of both profiting from and amplifying to billions, climate denial content.

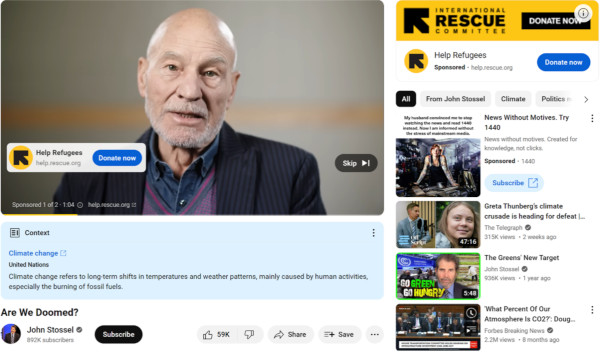

While YouTube says it does not monetize “old denial” claims, the CCDH found the policy was not fully enforced. These screenshots show ads for the International Rescue Committee served on and displayed next to the video “Are We Doomed?” from John Stossel. In the video, Stossel moderates a panel with members of denialist think tank The Heartland Institute, where one member claims, “There is no relationship between hurricane activity and the surface temperatures of the planet.” (Image: Screenshot of video by John Stossel, courtesy of the Center for Countering Digital Hate)

CURWOOD: To what extent can government play a role here in cleaning up social media? And to what extent is this just something that the free market is going to have to do?

AHMED: I think governments can mandate transparency of companies, so they explain how their algorithms work. They explain how their content enforcement rules work. I think they can explain how their economics work, how the advertising works, so we have more understanding of that as well. And you know, one of the biggest problems that advertisers have, is they often don't know where adverts are appearing. Do you know what sorts of organizations were appearing on these climate denial videos? The United Nations High Commission for Refugees, Save the Children, the International Rescue Committee. Three bodies which are dedicated to dealing with climate change were accidentally having their ads appearing on these climate denial videos. And they will be furious. And I think that when the market has more transparency, when people identify problems, as our research does, then I think that people will take action.

O’NEILL: That’s Imran Ahmed, CEO and founder of the Center for Countering Digital Hate. He spoke with Living on Earth host Steve Curwood. We reached out to YouTube for comment and received a response from a YouTube spokesperson that reads in part: “Our climate change policy prohibits ads from running on content that contradicts well-established scientific consensus around the existence and causes of climate change.” The full statement is on the Living on Earth website, loe.org, where you can also find the rest of our climate disinformation series.

Full YouTube Statement: “Our climate change policy prohibits ads from running on content that contradicts well-established scientific consensus around the existence and causes of climate change. Debate or discussions of climate change topics, including around public policy or research, is allowed. However, when content crosses the line to climate change denial, we stop showing ads on those videos. We also display information panels under relevant videos to provide additional information on climate change and context from third parties.” - YouTube Spokesperson

*Editor’s Note: To clarify, TikTok is not owned by Meta.

Related links:

- The Center for Countering Digital Hate | “The New Climate Denial: How Social Media Platforms and Content Producers Profit from Spreading New Forms of Climate Denial”

- Living on Earth “Part I” Fossil Fuel Deception with Naomi Oreskes

- Living on Earth “Part II” Climate Deception with Naomi Oreskes

- Find YouTube parent company Google's climate change policy here

[MUSIC: Julian Lage & Chris Eldridge, “Greener Grass” on Mount Royal, Free Dirt Records]

DOERING: Just ahead, how ancient redwood trees seem to come back to life after devastating wildfires. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Clarinet Fusion, “King of the Road” recorded live in the summer of 2021, by Roger Miller/arranged by Keith Terrett]

In Defense of Little Foxes

RedFox takes a bite out of the squirrel Mark Seth Lender nicknamed “The Fat Man.” (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill. Over the years, Living on Earth Explorer in Residence Mark Seth Lender has peered through his camera lens at wild animals all over the world, from cheetahs to polar bears to wildebeest. But sometimes, memorable encounters happen right in his own backyard.

LENDER: RedFox is sitting on the stone garden wall, her expression doubtful. On the other hand, she wouldn’t be out in the open like that if she didn’t feel safe. We have a not quite entente cordiale. She thinks she belongs. And I love to see her.

Today that love was put to the test.

Valerie’s yelling, “Mark! Mark! She’s got a squirrel!”

“She” can only be RedFox.

Grab the camera, down the stairs two at a time; not a thought for the squirrel.

Until I see him:

The squirrel is a squirrel that I know. The Fat Man, named after Sydney Greenstreet’s character in The Maltese Falcon, and just as unsavory. The Fat Man has done better than the birds on sunflower seeds I put out, driven out the other squirrels. And he’s unfriendly. Now, too much success has caught up with him. RedFox has him limp in her jaws.

RedFox fixes Mark Seth Lender with a look. (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

She puts him down – game over – except it isn’t. He comes to and escapes.

She catches him, he breaks free, turns on her - The Fat Man is like a cornered tiger - and I am impaled. I want to let things take their course but I know him.

I move quickly toward the fox.

RedFox retreats maybe ten feet. Stops. Does not growl. Grimace. She just looks. Head tilted a little. Eyes not too wide nor narrow:

“What are you doing?” This is what that look means, clear as day, “What are you doing?”

I am breaking the law, that’s what I’m doing. And this is a law you do not break.

Knowing even a little who that squirrel was, look what I did. Why only him? Why only those that we know? Why not everyone.

O’NEILL: That’s Living on Earth Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender. For pictures, check out our website, loe.org.

Related links:

- Read the corresponding field note for this essay

- Visit Mark Seth Lender’s website

[MUSIC: Amanda Ventura, harmonica with Tommy Hegel, acoustic guitar, “The Way” on Pocket Session-Take One Estudio, on YouTube.]

"Phoenix" Trees Rise from the Ashes

Sprouts at the base of a redwood tree in February 2021, 5 months after the 2020 CZU lightning complex fire. (Photo: Melissa Enright, co-author of the study “Old Reserves and Ancient Buds Fuel Regrowth of Coastal Redwood After Catastrophic Fire”)

DOERING: Coast redwood trees are the tallest in the world at over 300 feet, and that height, as well as their thick bark, usually keeps their upper branches and needles safe from wildfires. But in the hot, dry summer of 2020, the CZU Lightning Complex Fire climbed straight into the heart of California’s Big Basin Redwoods State Park and up into the crowns of its iconic redwood trees.

[FIRE SFX]

DOERING: As the Park lay smoldering, rangers returned to see what remained.

RANGER 1: We finally make it to Park headquarters and there’s nothing left.

RANGER 2: The visitor’s center, the shop, residences, every vehicle in the fleet: gone. It’s all gone. And on top of that, you know, we talk about facilities like they’re structures, our trail system got hammered. We lost everything. You can say, we lost everything.

Study coauthor Lissy Enright took this photo of what remained of the Big Basin Redwoods State Park visitor center after the fire. (Photo: Lissy Enright)

DOERING: 97% of Big Basin had burned, including almost all of its coast redwood trees. Though many still stood, they were completely blackened all along their trunks, without any needles intact. But incredibly, within a matter of months these redwoods began to grow fresh, bright green needles. A group of Northern Arizona University scientists and other researchers visited the forest after the fire to learn its secret. Lead author Drew Peltier is an assistant professor in the School of Life Sciences at the University of Nevada Las Vegas, and he joined us to explain the science behind this stunning recovery.

PELTIER: Redwoods are really remarkable in that they have this ability to resprout after fire. They have a lot of really neat fire adaptations, they have super thick bark at the base up to a foot thick. They're also just really, really tall, which helps to survive fires, because you're often above the flames. And all those things mean that they usually survive fire events, it seems like, and then they have this remarkable ability to regrow new leaves after the fire, even if they lose them all. And so we were there to kind of study these resprouting individuals. And so what you have now a couple years later, is what we've been calling these green telephone poles. So these trees that have lost all their branches, but then they've resprouted new foliage all on their stems. And so yeah, it's much less shady, it's a much different place than it was before the fire.

DOERING: That sounds like a really strange and different kind of forest to stand in. And you're talking about [LAUGH] green fuzzy telephone poles. So the sprouts aren't just coming from the base of these trees.

PELTIER: No, these trees resprouted from everywhere: from the roots, from the stems, from branches if they managed to keep some of them. It's really kind of all over these trees. They produced a really gigantic amount of new foliage from these buds that they maintain. And so it seems like they were really primed to very rapidly recover after this fire event.

DOERING: So tell me about this transformation. I mean, given this devastation with, you know, this intense fire that went all the way up into the crown and burned all of the green needles—for these trees to then have all of this new green growth. How is this happening?

PELTIER: Yeah, so the way that these trees do this is there are kind of two key adaptations that our study was really about. The first is that, well, they store a lot of energy, because you need energy to grow. And when you don't have any leaves as a tree, you're not bringing in any new energy through photosynthesis. And so one of the things we did was to look at sort of the age, essentially, of those energy reserves or carbon reserves, and basically that's just in the form of things like sugars and starch. And so by using this process called radiocarbon dating, we were able to estimate that some of these carbon reserves were on the order of 50 to 100 years old. So to think about that another way, what that means is that carbon that was photosynthesized from the atmosphere, potentially back in the 1940s and 50s, is being used to regrow new leaves now after fire. So really, really long-term storage of energy. And kind of the second part of that is they have to have the anatomical tissues to grow these new leaves. And so the other really amazing thing that we found is when you look in the wood underneath these, these little sprouts coming out of the stem, what we saw was a line going all the way to the center of the tree, which basically means that these sprouts arose from really ancient bud tissue, so buds that were sort of as old almost as the tree itself, which in some cases could be thousands of years. So that's just sort of was shocking to us. It's this really long-term preservation of bud tissue. And those two things together—really large amounts of very old carbon reserves and lots of really ancient buds—means these trees were very prepared in a sense.

A small sprout emerging from a very large redwood. (Photo: Drew Peltier)

DOERING: And it sounds like if these buds are just sprouting now, all this time they've been lying dormant, they go all the way back to in some cases when that tree first sprouted. So somehow, it sounds like, the tree knew, you know, this is my savings account. I need to keep this around in case I need it someday. And this is the moment.

PELTIER: Yeah, I mean, I guess that's one way to think about it, for sure. A useful comparison, I think, is to the giant sequoia in California. So these are the other giant tree species that lives in California. They unfortunately do not have this ability to do this resprouting thing. And a lot of those trees actually burned as well in 2020 and also in 2021. And those two fire events combined, I think, killed around 15% of the largest giant sequoia in California. So 15% of the largest giant sequoia on Earth. Because essentially, when those trees lose all their leaves, that's kind of it. It’s game over. So this resprouting adaptation, this maintenance of buds for really long time periods, is a super important adaptation, it seems like, to extreme wildfire.

DOERING: So not all trees can do this.

PELTIER: Definitely not. It's pretty common in, you know, what we call broadleaf trees. You know, what you think about in the East with the autumn colors, things like maples and hickory, lots of those trees, particularly oaks, will resprout from the base. It's almost entirely absent in pines, and it seems to be a thing in the Cupressaceae, so this is stuff like junipers, cypress, redwood.

DOERING: So you mentioned these carbon stores that are really old. That's the way that these trees were able to grow new tissue, new green needles after this fire. Where exactly are they storing this and how?

A giant sequoia where Drew Peltier installed a phenocam, a digital camera used to monitor ecosystem dynamics over time. Many giant sequoias are between 250 and 300 feet tall, the tallest being about 325 feet high. (Photo: Drew Peltier)

PELTIER: Yeah, so, everywhere, is the answer to that question. In all living cells. You know, animals have fat cells. That's how, you know, you and I, and my dog, store our energy. But plants do not have that. Some of them store lipids, but mostly they store energy in the form of sugars and starches. And those are stored pretty much throughout the tree. Some trees have specialized below-ground organs, but in redwoods it's everywhere in living cells. So in branches, in leaves, in the stem, in roots. But the oldest reserves seem to be in really, really deep tree rings.

DOERING: So how did you actually figure out how old these stored carbon reserves were?

PELTIER: Yeah, so we did a bunch of sampling for this study, but the main thing we did was simply just to collect some of these little sprouts. So Lizzy Enright, who’s a co-author on our paper, was out there in just a couple of months after the fire, and she covered parts of the bark, basically, to keep those sprouts from photosynthesizing. So they only were drawing on stored carbon reserves. And then we just sort of clipped them when they got big enough and used them for analysis. And so the way that we actually figure out the age of the reserves that were used to build those sprouts, is based on what's called radiocarbon dating. And so the way to think about this is kind of by using a bookmark, and the bookmark in time is basically atmospheric bomb testing in the 50s and 60s. And so, you know, this was a pretty strange period in human history, but one thing that did happen was we basically doubled the concentration of radiocarbon in the atmosphere. Since that time, we've stopped testing nuclear bombs in the atmosphere, which is great, and so as a result, that concentration of radiocarbon has dropped off over time. And so what we can do is simply just look at the carbon that's in this little sprout and see how much radiocarbon is there now using what's called accelerator mass spectrometry. And by comparing it to that kind of annual record that we have of radiocarbon, we can estimate how old it is. And so I say how old, but what I really mean is that's a measure of how long it's been since that carbon was photosynthesized from the atmosphere. It's a measure of sort of how long that sugar has been sitting in that tree before it was used.

This is a cross section of a branch showing the "bud trace" of a sprout. These same structures are present on the main stems of these resprouting redwoods, showing the buds that grew these sprouts may be thousands of years old. (Photo: Drew Peltier)

DOERING: So how does your research add to previous knowledge of tree growth?

PELTIER: So we have a lot of models of the global climate system, and what are called dynamic global vegetation models, or terrestrial vegetation models. And a lot of these make certain assumptions about how tree growth works, because tree growth is a really important process in the global carbon cycle. Forests pull huge amounts of carbon out of the atmosphere every single year and so kind of having a good handle of that and being able to predict that process going forward is a really important constraint on atmospheric carbon dioxide, basically. One assumption of many, many models about how tree growth works is that there's basically little or no storage of photosynthate or carbon reserves over time. And so what we've shown is not only are there really, really old reserves present in these very old trees, but also there are pretty substantial amounts of them. So in one estimate, it seems possible that there were perhaps hundreds of kilograms of 50-year-old carbohydrates in these trees, in the old ones. And so that's like a small motorcycle of sugar from 50 or 60 years ago. So it's a pretty big amount.

DOERING: Yeah, that is fascinating. So not only is this a story about how these forests are being affected by climate change induced impacts, like wildfires that are getting worse, but also we're learning potentially how we can improve our climate models.

PELTIER: Definitely. There's more and more research that I'm doing, at least, this is something that I work on, that basically shows that trees have this so-called memory of past climate, and they respond to their environment over really long timescales because they live a really long time. And so this storage of carbon reserves is one mechanism for how that works. So we know, for example, drought can leave really long legacies on tree growth, where trees grow more slowly for up to five years after drought events. And so there are similar examples of that in the literature, but this is sort of how that works, basically. Trees are doing photosynthesis all the time, they're putting energy into this kind of gas tank of sugars and starch, and they're using it to grow at different times. And when times are bad, maybe they draw a little bit more on this gas tank, and when times are good, maybe they put more in. But what this study shows is that there are really, really old energy reserves in that pool of carbon, at least in old trees. You know, some of these trees were upwards of 2000 years old.

DOERING: What does it feel like to study trees with such long lifespans compared to ours?

Drew Peltier at the top of a giant sequoia installing a new phenocam to monitor some fire impacts in the Mariposa Grove in Yosemite National Park. (Photo: George Koch, co-author of the study “Old Reserves and Ancient Buds Fuel Regrowth of Coastal Redwood After Catastrophic Fire”)

PELTIER: Well, I can answer that by an experience I had recently in a different tree species, but recently I was in Yosemite in the Mariposa Grove in giant sequoia trees, basically, and we got the opportunity to collect some tree cores. And I took a tree core from one of these giant sequoia that was just really, really big and had all these fire scars. And when I took the core out it became immediately obvious, you can tell when the rings are really, really small and really, really close together, that this tree was just thousands of years old, and I cried, basically. It was just a really emotional experience for me. I mean, they're, you know, I think everyone has to go to these old growth redwood groves and giant sequoia, because the pictures just do not do it justice. You know, when you go, I assume you'll have the experience of trying to take a picture on your phone, and you just can't capture it unless there's like a bus in there or something for scale. They are just kind of beyond belief in terms of how large they are, and they're really just magical, really important places that I think we need to preserve.

DOERING: Drew Peltier is an assistant professor in the School of Life Sciences at the University of Nevada Las Vegas. Thank you so much, Drew.

PELTIER: Thanks very much for having me. It was great to chat with you.

Related links:

- Nature Plants | “Old Reserves and Ancient Buds Fuel Regrowth of Coastal Redwood After Catastrophic Fire”

- Learn more about Drew Peltier

[MUSIC: Neena Goh “Only Time (Instrumental)”]

O’NEILL: Next time on Living on Earth, the latest book from Pulitzer Prize finalist Elizabeth Rush takes readers to the glaciers at the ends of the earth.

RUSH: I really had no idea [LAUGHS] how far away this place would be. It literally took us a month to arrive. From southern Chile, we started to cross the Drake’s Passage, which is considered the wildest ocean in the world. And so you tend to get really heavy, high seas and big storms. At one point, a gigantic refrigerator slammed across the lab. And then you get across the Drake’s Passage and then suddenly you’re in iceberg territory. Our ship, an icebreaker, is made to ride up on top of ice floe, which is relatively flat sea ice. It’s not made to like run into an iceberg!

O’NEILL: That’s next time on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Keola Beamer, “Ku’u Lei ‘Awapuhi Melemele (My Yellow Ginger Lei) & Pua Be Still” on Moe’uhane Kika – Tales from the Dream Guitar” Ku’u Lei… by Darby & Emily Taylor/Abbie K. Wilson, and John Keawehawai’i/Pua Be Still byBill Ali’iloa Lincoln, Dancing Cat Records]

O’NEILL: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Quentin Bell, Paloma Beltran, Josh Croom, Swayam Gagneja, Sommer Heyman, Mattie Hibbs, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Sarah Mahaney, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari. We welcome interns Karen Elterman and Caitlin Quirk this week.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Allison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts, and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments@loe.org. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth