February 2, 2024

Air Date: February 2, 2024

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Biden Pumps Brakes on Gas Exports

/ Halle ParkerView the page for this story

The Biden Administration has paused new export permits of liquefied natural gas over concerns that these enormous facilities would emit millions of tons of greenhouse gases every year. Reporter Halle Parker of WWNO in New Orleans joins Host Jenni Doering to discuss why LNG exports have been rising in recent years and the impact they are having on the Gulf Coast and the global climate. (12:35)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Living on Earth Contributor Peter Dykstra joins Host Jenni Doering with news of a study that found hermit crabs are using plastic trash as their homes instead of seashells. Also, New Jersey approves two major offshore wind projects that could power 1.8 million homes. And in history, they remember when Jacques Cousteau published The Silent World and revealed the mysteries of the oceans. (04:44)

Renewable Power Surge in China

View the page for this story

China surged ahead of other countries in 2023 to add 66% more wind power than it had before and bring online as much solar energy as the entire world had developed in 2022. Isabel Hilton, founder of China Dialogue, joins Host Aynsley O’Neill to examine the geopolitical and economic implications of China’s dominance in the renewable energy sector. (10:22)

Journey to a Melting Glacier in Antarctica

View the page for this story

Thwaites Glacier in Antarctica holds enough ice that its melting could raise sea levels worldwide by 2 feet, but it’s so remote that until recently no one had ever approached where it meets the sea. Elizabeth Rush was a writer-in-residence on board the first research icebreaker to visit Thwaites and she chronicles the journey in her new book The Quickening: Creation and Community at the Ends of the Earth. She joined Living on Earth Host Steve Curwood to share the experience of witnessing the glacier’s unraveling and the crucial data the scientists on board unearthed. (19:01)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

240202 Transcript

HOSTS: Jenni Doering, Aynsley O’Neill

GUESTS: Isabel Hilton, Halle Parker, Elizabeth Rush

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Halle Parker

[THEME]

O’NEILL: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

O’NEILL: I’m Aynsley O’Neill

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

President Biden puts a pause on new gas export projects.

PARKER: These gas export terminals are also nicknamed “carbon bombs.” There’s one facility that’s proposed on the Gulf Coast. It’s called CP2 and it would, if it was constructed, actually emit up to 10 million metric tons of carbon each year.

O’NEILL: Also, China leads the world in building new renewable energy.

HILTON: China is building absolutely enormous industrial-scale solar parks in the western deserts. They’ll have a capacity equivalent to two or three times the Three Gorges Dam when completed, for example. So that’s a truly massive investment in renewables.

O’NEILL: That and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Biden Pumps Brakes on Gas Exports

The Calcasieu Pass liquefied natural gas (LNG) export facility in Cameron Parish, Louisiana, US, is operated by Venture Global Calcasieu Pass, a subsidiary of US-based LNG production company Venture Global LNG. (Photo: Halle Parker)

O’NEILL: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston this is Living on Earth. I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

The Biden administration has paused new export permits of liquefied natural gas over concerns that these enormous facilities would emit millions of tons of greenhouse gases every year. Environmentalists hailed the move and canceled a sit-in protest planned at the Department of Energy headquarters this month. DOE said that it will conduct an environmental review focused on better understanding energy costs and methane emissions from liquified natural gas. The last review of “LNG” export projects was in 2018 when capacity was 4 billion cubic feet per day, according to DOE. That capacity has increased by more than threefold and would rise further if the paused projects come online. Halle Parker is an environment reporter on the coastal desk of station WWNO in New Orleans. She’s working on a forthcoming 3-part series for WWNO covering the export boom and following American gas around the world and she joins us now. Welcome back to Living on Earth Halle!

PARKER: Thanks for having me again, Jenni.

DOERING: So Halle, the Biden administration decided to pause multiple new LNG or liquefied natural gas facilities. What are the politics involved in this decision?

PARKER: Yeah, so this was a really, really huge decision. And it was the result of years of protest from different environmental activists on the coast, different local groups on the Gulf Coast, where this proposed build out of liquefied natural gas export terminals is really happening. And so then over the past few months, a bunch of national green groups started to get involved and now that it is an election year, they really got strategic with what they were asking for. They knew that, you know, it wasn't going to be possible to just completely shut down liquefied natural gas production in the US. I mean, it's a huge industry and it's growing right now. But they knew that they would legally be allowed to ask for a pause, like a little bit of a hiatus for the Biden administration to actually be able to sit and review whether all of these facilities that are being proposed and are coming to their desk are actually needed. And so that's what this pause is allowing them to do.

DOERING: And you mentioned these green groups, why do they care so much, especially when natural gas has sometimes been called a bridge fuel from dirty sources like coal in the past?

A gas tank at the Cameron LNG facility in Hackberry, Louisiana. (Photo: Halle Parker)

PARKER: So, yes, gas has allowed us to transition, especially us as a country, to transition from dirtier fuels like coal before but these gas export terminals are also kind of nicknamed climate bombs or carbon bombs. There's one facility that's proposed on the Gulf Coast, it's called CP2. And it would, if it was actually constructed, become the largest export terminal in the country. And beyond just exporting gas, it would emit up to almost 10 million metric tons of carbon each year. To put that in a context that is almost the same amount of the annual emissions that Costa Rica puts off in a year. So a whole country.

DOERING: Halle, the Gulf Coast of the US is a really important place for gas refining and for exports already. So what kinds of impacts could some of these proposed projects like CP2 have on Louisiana's coastline?

PARKER: So there are a lot of concerns with these facilities. There's also a lot of people who are advocating for them, because where they're being proposed, and Louisiana is actually for the most part, this area in Southwest Louisiana, a parish called Cameron Parish. And they've historically relied on the offshore oil and gas drilling industry for a lot of their work. But that industry has declined at times, they've also been hit by a lot of different hurricanes. So they've seen their population cut by a lot because people haven't been returning. And so they've kind of viewed this gas industry as a new way to start building resources again, and start paying for what's needed to take care of their citizens. And it is bringing in a lot of tax revenue for that area. But, then there's also the concern of the fact that these facilities are being built in these coastal areas that, again, are known to be hit by hurricanes. And so there's a question of safety there. And also, they're worried about, you know, shutdowns. There's a plant that already exists down in Cameron parish in Southwest Louisiana called Calcasieu Pass LNG. The company who operates it Venture Global, has said that it's safe, everything is fine over there, but they have had a lot of different issues in terms of reporting blackouts that have led to releases of pollution that weren't intended. And all of that has kind of like raised questions for some of the residents living nearby.

Gas flaring from the Calcasieu Pass LNG in Cameron, Louisiana. Gas flaring puts multiple chemicals out into the air including benzene, which can give people who live nearby headaches, tremors and irregular heartbeats. Benzene can also cause cancer. (Photo: Halle Parker)

DOERING: Yeah, what have you been hearing from local residents in the area?

PARKER: Yes, so I've talked to quite a few of them. A man that I've spoken to a lot John O'ler he's a retired environmental engineer. And he lives in a trailer, less than a mile from Calcasieu Pass. And he has said that he sees flaring almost every night, or at least he did in their first year of operation. And he also has the receipts, because each time he sees that flaring, he's taking photos and documenting them. And so he is one of the ones who is much more skeptical of whether this direction is the right one for the community to go in. But then you go to maybe like a public hearing, like I've gone to where people who are working for companies who are maybe supplying catering or doing cleaning services or maybe their son works at the plant, they're much more likely to have a more positive outlook on what opportunities these plants present.

DOERING: And I understand that the country started exporting LNG in 2016. And we're now one of the biggest exporters. How did we get here?

PARKER: Yeah, so to figure out how we got here, we'd have to go all the way back to talking about when horizontal fracturing became a thing and that you're more likely to have heard it called fracking. And that technology made it, you know, so easy for us to get gas over in the US that we started to have this surplus. And that's why historically, natural gas prices in the US have been so low why everybody calls gas, this, you know, this cheap resource, cheap way to get energy. But over time, you've seen the country commit to transitioning away from fossil fuels. And you've also seen the oil and gas industry start to look for new markets for their product. So liquefied natural gas exports are a way for them to expand who their customer base could be. Historically, the gas that has been drilled in the US has just, you know, stayed in the US. And that's through a system of pipelines, and it's usually transported through. But opening up the world to LNG being able to cool down this gas and ship it in actual vessels overseas gives the gas industry, more countries to sell their product to.

Calcasieu Pass LNG in Cameron, Louisiana. President Biden has paused pending liquified natural gas export terminals like the one pictured above while his administration reassesses how best to determine whether additional infrastructure serves the public. (Photo: Halle Parker)

DOERING: So there's a huge push from industry itself. And of course, the Biden administration has pretty strong climate goals. But in fact, it has been expanding liquefied natural gas production even more. Why is that?

PARKER: Yes. So to understand that, we'd have to go back a couple years to 2022. And remind ourselves of when Russia started invading Ukraine. When that happened, you know, the European Union has historically relied on Russia to supply gas. But in order to try to pressure Putin to stop this invasion, they were really looking to cut off Russian gas. And then the Nord Stream, the major gas pipeline, that would be bringing that product in, ended up exploding. And those are still not operating. So there's this huge concern that Europeans wouldn't have enough gas to heat their homes during the winter as a result. That meant President Biden made this big pledge to ramp up our exports of gas in order to help and meet the need and support our quote unquote, allies. And that really opened up this like huge faucet of proposals from the gas industry to build these new export plants. Although I will say a lot of these new export plants won't be done for years and this crisis with European energy might not exist them.

DOERING: So you mentioned that it takes in some cases, years for these projects to come online. But some folks are looking at the long term of the climate and wondering, you know, how will this kind of expansion of liquefied natural gas affect the world's ability to meet the Paris Agreement, climate goals of keeping warming below 1.5 degrees Celsius? What's the information we have on that?

Environmental advocates Jade Woods of CIEL and James Hiatt, founder of For a Better Bayou pose in front of Cameron LNG with German Parliament member Kathrin Henneberger. (Photo: Halle Parker)

PARKER: Yeah, absolutely. Just to say that is a huge reason why this pause on LNG exports is happening in the first place. There's been several reports that have come out, one came out last year from the Natural Resources Defense Council and it talks about how LNG really isn't a very effective strategy to actually reduce our planet warming emissions. And they actually conclude that it could make it nearly impossible for us to keep global temperatures from increasing above that 1.5 degrees Celsius mark that you mentioned, Jenni. And that's partially because of the lifecycle of natural gas, you know, it's very, depending on where they're getting the gas from. It can be very leaky, there's a lot of methane emissions associated just with gas drilling. And in some cases, that can mean that LNG produces even more carbon than coal ultimately, if you look over the course of its whole lifecycle.

DOERING: Now given the geopolitical issues of Europe, cutting down on Russian gas, how are people in Europe responding to this move by the Biden administration?

PARKER: I haven't heard as much backlash from European countries over this. In fact, when Biden made this announcement, there were 70 lawmakers who are part of Parliament's across the EU, who wrote a letter to support the decision saying that they want Biden to take a step back and figure out how many export facilities are actually needed versus just you know, letting this bonanza continue indefinitely. Just to be able to like have that research and figure out if all of these facilities are in the public's interest. I had spoken with a German environmental advocate a few weeks ago, and there's a coalition of more than a dozen environmental groups from Germany who had filed a letter asking the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission to deny permits for CP2 that really large facility planned in Louisiana that we talked about earlier. And that's partially because they felt there were human rights implications because of where these facilities are being built. Like I mentioned, a lot of these communities are already historically dependent on fossil fuels. And some of them are also already heavily industrialized. So there's this question for some over in the EU about whether they might be exporting human rights violations in exchange for importing the gas they need to heat their homes.

Halle Parker reports on the environment for WWNO's Coastal Desk. (Photo: Courtesy of Halle Parker)

DOERING: That sounds like a real moral dilemma.

PARKER: It absolutely is.

DOERING: So coming back to these major liquefied natural gas projects that the Biden administration has put on hold for now. What’s next?

PARKER: So what's gonna happen is the Department of Energy is going to start this review. Through the course of their analysis, they're going to start weighing different factors from effects on the economy, from effects on health, from effects on the climate, and use the information that they gathered to issue some sort of determination about whether the development of liquefied natural gas export plans are in the country's interest. When I was on a call with Secretary Jennifer Granholm, she was not really clear about how long that process will take. But there is a belief that it will likely take through the end of this year so that pause will likely still be in place by the time we are casting our votes in November.

DOERING: Halle Parker is a reporter for WWNO in New Orleans. Thank you, Halle.

PARKER: Thanks, Jenni.

Related links:

- Learn more about coastal desk reporter Halle Parker

- Carbon Brief | “Q&A: What Does Biden’s LNG ‘Pause’ Mean for Global Emissions?”

- The White House | “FACT SHEET: Biden-Harris Administration Announces Temporary Pause on Pending Approvals of Liquefied Natural Gas Exports”

- Reuters | “Biden Pauses LNG Export Approvals After Pressure From Climate Activists”

- NRDC | “NRDC Report: U.S. LNG Exports Undermine Climate and Environmental Goals”

[MUSIC: Mississippi John Hurt, “Candy Man” on King of the Blues, by traditional/Rev. Gary Davis/Mississippi John Hurt]

O’NEILL: Coming up, 2023 brought an impressive surge in renewable power worldwide, driven mainly by China. That’s just ahead. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Amy Turk, “When You Wish Upon a Star” single, by Leigh Harline/arr.Amy Turk]

Beyond the Headlines

Researchers reviewing online imagery found 386 examples of hermit crabs using artificial shells such as plastic caps. (Photo: Eric Heupel, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

O’NEILL: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

Down in Georgia, Living on Earth Contributor Peter Dykstra has some stories from beyond the headlines he’d like to share. Hey, Peter, what’s on tap this week?

DYKSTRA: Hi Jenni, we've got a lot of stuff from the water. Number one is based on a study from a team of scientists in Poland, publishing in the Science of The Total Environment Journal, and they have found hermit crabs, those adorable little crustaceans you see running up and down the beach whose shells are borrowed, usually, from other species. But in this study, they found 386 examples of hermit crabs who found garbage as a more acceptable home than another animal's shell. Those more innovative hermit crabs, if that's in fact what they are, were using plastic bottle caps, sometimes small pieces of metal or glass. And while this doesn't constitute any kind of a majority of hermit crabs, hermit crabs could be the latest manifestation of how plastics and other manmade materials are beginning to take over corners of marine life we would have never imagined they'd take over.

DOERING: Well, it certainly does speak to the volume of plastic trash that we're putting out into the environment. You know, Peter, I don't know if you're on TikTok these days. But one of my favorite TikTokers is actually taking some of these hermit crabs, like going out and finding the ones that have these plastic bottles as their home, and offering them a natural home, a shell, and they always move in and seem to enjoy it.

DYKSTRA: I'll have to check it out.

DOERING: Well, Peter, what else do you have for us beyond the headlines this week?

New Jersey recently awarded contracts for two large offshore wind projects. (Photo: Jess Stromberg, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

DYKSTRA: My home state of New Jersey, often known as the Garden State, occasionally depicted as the mafia state, lost two big offshore wind projects last year. But after losing those two projects last year, that could have powered a million homes, they're in the midst of signing up two new projects for not just a million but 1.8 million homes worth of electricity from offshore windmills.

DOERING: That is quite a lot of wind power, Peter.

DYKSTRA: It is. And it's a sign that even though there was a little bit of a glitch in the growth of wind power, the confidence is there to make these things work and battle against climate change from the overuse of fossil fuels.

DOERING: Sounds like wind in the sails of offshore wind.

DYKSTRA: That's what it is exactly.

DOERING: So Peter, for history this week, are we sticking with this ocean theme?

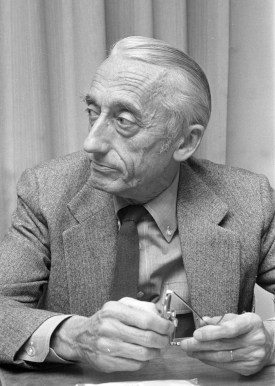

Oceanographer Jacques-Yves Cousteau was known in part for his book The Silent World, published on February 3, 1953, and for his 1956 documentary of the same name. (Photo: Hans Peters / Anefo, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

DYKSTRA: Yes, we're sticking with this ocean theme. On February 3, 1953, one of the greatest ocean explorers ever, Captain Jacques Cousteau, published his smash hit book, The Silent World. Just absolutely riveting, breathtaking, never-before-seen images of what lies below the ocean surface. Cousteau followed up this book that sold 5 million copies. Later, he did The Silent World as a documentary that eventually won an Academy Award, and he became the master explorer, bringing those images from beneath the oceans to people's living rooms. Cousteau was always a hero of mine, with his documentaries on ABC, and later on TBS. Cousteau kept producing this kind of work right until his death in 1997, and his children and grandchildren continue the work today.

DOERING: I've heard so many people talk about just how influential Jacques Cousteau's work, and bringing the undersea world to the rest of the world, was in shaping our understanding of the oceans.

DYKSTRA: Really, anything you see that's in documentary form, about the oceans or about the sea floor was preceded and certainly inspired by the work of Captain Cousteau.

DOERING: And the ocean is a place we're still discovering. I mean, it's been said that we've mapped more of the moon than we have the ocean floor.

DYKSTRA: And hopefully we'll continue to discover it and protect it before we're discovering the downside, like hermit crabs wearing bottle caps.

DOERING: Well, thank you, Peter. Peter Dykstra is our Living on Earth contributor, and we'll talk to you again next week.

DYKSTRA: Okay, Jenni, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

DOERING: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth website. That's LOE.org.

Related links:

- Washington Post | “Majority of Land Hermit Crab Species Now Use Trash for Shells”

- Access the original study in Science of The Total Environment

- E&E News | “NJ Hits Reset on Offshore Wind, Approves Two Massive Projects”

- Learn more about Jacques Cousteau and The Silent World

[MUSIC: Paul Winter, “Ocean Dream” on Paul Winter: Greatest Hits, by H. Whale and Paul Winter, Earth Music Productions]

Renewable Power Surge in China

In 2023, China commissioned as much solar energy as the entire world did in the previous year. (Photo: Pixabay, Pexels)

O’NEILL: At the COP28 climate summit in Dubai, countries set a goal to triple global renewable energy capacity by 2030. It’s an ambitious target but in a new report the International Energy Agency, or IEA, says we’ve got a good shot of reaching it. Global renewables capacity grew 50% in 2023 to more than 500 gigawatts. And the main driver of that growth is China. Last year China surged ahead of other countries, adding 66% more wind power than it had before and bringing online as much solar energy as the entire world had developed in 2022. Isabel Hilton is founder of the China Dialogue group and a non-executive director of E3G, a climate think tank. She’s here now to speak with us about the implications of China’s dominance in the renewable energy sector. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Isabel!

HILTON: It's a real pleasure to be here, Aynsley. Thank you for having me.

O'NEILL: What sort of advantages does China have that's allowing them to produce this renewable energy at such an incredible scale?

HILTON: China is just the world's biggest industrial economy. And it has built up a capacity for producing extremely efficiently, for organizing supply chains extremely efficiently. It still has relatively low labor costs, and it is moving to very high rates of automation. The other thing I think that helps China to keep its costs down is that it's producing at scale for a very large domestic market and then an export market. China is building absolutely enormous industrial scale, utility scale, solar parks in the western deserts. They will have a capacity equivalent to two or three times the Three Gorges Dam when completed, for example. Not that many Western companies produce at that scale in that sector. And that's, you know, because China invested nearly 20 years ago and has built up its capacity since. So it's very hard to challenge it.

China dominates the supply chain of many renewable technologies, including electric vehicles. (Photo: Rathaphon Nanthapreecha, Pexels)

O'NEILL: So China is seeing such success in increasing their renewable sector. What does that mean for the rest of the world's economy?

HILTON: The problem is that it has gone to a level of dominance that this is felt to threaten the industrial economies of other G20 countries. There's a particular concern in the European Union about government subsidies in China, which are undermining the capacity of European companies to compete. And if you don't challenge that, as a trading practice, then every advanced industrial economy risks losing its own sector. We saw it in the past in solar panels, we're seeing it now, and this is going to be quite a big one, in electric vehicles. We have to move transport, essentially, to electric vehicles. The problem is that China is producing very good electric vehicles around 10,000 euros cheaper than a European manufacturer. And that's a massive price difference. Now, in a world where you're only thinking about climate, you would say, that's great, you know, let all those cars come into the European market. But if you look at the importance of the car industry, in the European market, so particularly in Germany, but also in Slovakia, in the Slovak Republic, for example, where there's a significant car industry and all the supply chains that feed that car industry, then you have a serious problem. You know, if that was to be undermined by cheap Chinese vehicles, you would get political backlash, economic downturn, you'd get a lot of unrest and unhappiness. So managing this is going to be the challenge of the year.

China is still building coal-fired power plants, despite its simultaneous massive rollout of renewables. (Photo: V.T. Polywada, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

O'NEILL: Well so what about some of these other global superpowers, the EU, the United States? How are they responding to China's progress and the global surge towards renewable energy?

HILTON: Well, the G20 economies are responsible for most of the emissions. But the good news is that the European Union and the United States both have strong policy commitments now to the energy transition. So the IRA in the United States is really important. And Europe has had a whole series of very important policy initiatives around a green transition. I think, though, that both in the European Union and in the United States, there is some concern about political opposition to the transition. The US election, for example, in November, where Donald Trump to come back, he has threatened to leave the Paris Agreement again, and to you know, drill for yet more oil. So that's discouraging. But, you know, the commitment, I think, still in Europe to the Paris Agreement and to the goals set, after the global stock take is pretty solid. And Europe could meet that tripling target, but it would depend slightly on there being no political obstacles or no political setbacks.

O'NEILL: What's the outlook in China right now? How are they faring in terms of, you know, obstacles that they might be facing? How's their economy doing? What's next after this scaling up all in terms of renewables?

Above, a vent stack at a gas processing station; gas is mostly made of methane, a powerful greenhouse gas. Reducing methane emissions now can have a significant benefit for the climate. (Photo: Clean Air Task Force, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

HILTON: The economy in general is not doing terribly well in China, and it's overshadowed by the slow-motion collapse of a very, very large property sector. China's also hitting some trade obstacles with the United States, with the European Union. And China's ambition to transfer from an export-oriented, investment- heavy economy to one that's far more consumer-led hasn't really worked because people's incomes haven't gone up enough. There's a lot of uncertainty following COVID. So people in China are just not spending the way they would need to to sustain the Chinese economy as substantially a consumer and service based economy. So we're still seeing a lot of investment in industrial capacity. And that's feeding into the problem we just discussed, which is overproduction of lots of renewable technologies, which are then going to be dumped on global markets and cause further trade friction. That's a big problem. The other problem in terms of Chinese mitigation, so that's reducing emissions, is a question of energy security. Because we're in an age of geopolitical tensions, security has come right up the agenda for China and energy security is a concern because every fossil fuel that China consumes except for coal has to be imported. And although China has increased its imports of both oil and gas from Russia, there is still a concern about were the security situation to deteriorate further, China likes to have a kind of domestic fuel to fall back on. And unfortunately, that tends to be coal. So we're still seeing in China more building of coal fired power stations. But fortunately, the dial is moving towards the more positive side. You know, when you look at who is likely to be able to meet that tripling of renewable capacity by 2030, China's well ahead. China would have no great trouble meeting that goal.

O'NEILL: Isabel, despite this good news about the world possibly being on track to meet the UN agreed target of tripling renewables by 2030, the IEA has warned that the goal still isn't going to be enough to keep warming under 1.5 degrees Celsius above the preindustrial levels that we're looking for. What needs to be done in order to push beyond what we previously thought was possible, in terms of this renewable energy capacity?

Isabel Hilton is the founder of the China Dialogue group and a non-executive director of E3G, a climate think tank. (Photo: Anne Heslop)

HILTON: I think you probably have to look at it from two dimensions. We are still emitting an awful lot of carbon and methane. We can buy ourselves a bit of time by cutting way back on methane emissions. And that was a concern at the last Conference of the Parties. And we have seen a number of countries sign up to a methane pledge. The point about methane is that it's a relatively short-lived greenhouse gas, so that if you reduce levels of emission now, you do get a benefit within a decade, whereas with carbon, it takes 100, 200 years to see the benefit of reducing emissions now. The second thing, of course, is to reduce all emissions, much faster. Global emissions have not yet peaked. After 30 years of discussing this, we have not peaked our emissions. We really have to move faster on that. So yes, of course, we need to accelerate the deployment of renewable energy, there are a lot of administrative barriers, but that isn't going to do it unless we simultaneously reduce the carbon emissions from all sorts of sectors. It's not rocket science, if you like, but there are a lot of things in the way we have done things in the past that will need to change. And one major thing is finance, you know, getting the World Bank, the multilateral organizations to invest- to stop investing, first in fossil fuels, which banks and multilateral still do. Stop doing that, and just put the money into renewables instead. And finally, there are a lot of countries that have yet to build energy systems. And it's very important that those developing countries, those emerging economies, build renewable systems rather than passing through that phase of heavy fossil-based economies that until relatively recently, we thought was necessary for a developing country to boost its economy. That is no longer the case. But they will need investment and they will need advice and technology in order to do that. But we would certainly avoid another big problem if we manage to do that.

O'NEILL: Isabel Hilton is founder of the China Dialogue group and a non-executive director of E3G, a climate think tank. Isabel, thank you so much for joining me today.

HILTON: It's been a real pleasure, thank you.

Related links:

- The International Energy Agency | “Massive Expansion of Renewable Power Opens Door to Achieving Global Tripling Goal Set at COP28”

- The Financial Times | “Renewable Energy Surge of 50% Driven by China, IEA Says”

- Read more about the China Dialogue

- Read more about E3G

[MUSIC: Derek Fiechter, Brandon Fiechter, “Calligraphy” on Chinese Festivals]

DOERING: Coming up, a journey to a melting glacier at the ends of the earth. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Bela Fleck and the Flecktones, “Lovers Leap – Live at the Quick” on Live at the Quick, Sony BMG Music Entertainment]

Journey to a Melting Glacier in Antarctica

Thwaites glacier surrounded by sea ice. (Photo: Elizabeth Rush)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

The so-called “Doomsday” glacier in Antarctica known as Thwaites holds enough ice that its melting could raise sea levels worldwide by 2 feet. And seas could rise 10 feet or more if the loss of Thwaites destabilizes the massive West Antarctic Ice Sheet that it’s holding back. But because the climate is entering uncharted territory in human history, most climate models don’t account for that amount of sea level rise. So to help fill the data gap, in 2019 a few dozen scientists and crew made the long and stormy journey to Thwaites. Also on board their ship were a couple of journalists and the expedition’s writer-in-residence Elizabeth Rush. Her 2023 book The Quickening: Creation and Community at the Ends of the Earth chronicles the two-month expedition. But The Quickening also weaves in Elizabeth’s personal story of another epic journey.

RUSH: The amount of paperwork you have to do to go to Antarctica is like astronomical, and I can still remember getting this sort of like huge packet in the mail and reading one sort of line in it that said, pelvic exam. And it turns out that pregnant people aren’t allowed to deploy to the ice. I had really wanted to start trying to get pregnant around this time.

O’NEILL: And putting that off would mean Elizabeth would be 35 when she could finally start trying for a baby, right on the edge of the supposed “fertility cliff,” though she points out that’s somewhat of a myth. But the ice was calling, and she sensed it had a story to tell about what was happening to our rapidly changing planet, the very world she hoped to someday bring a child into. Elizabeth Rush recently joined Host Steve Curwood to talk about the journey to Antarctica and what it revealed.

The cover of The Quickening: Creation and Community at the Ends of the Earth. (Image: Courtesy of Elizabeth Rush)

CURWOOD: The subtitle of your book calls this the "Ends of the Earth," Antarctica. And you have a pretty strong telling of how difficult it is to get to the Thwaites Glacier. Talk to me a bit about the geography of this place and what makes it so doggone difficult to get to.

RUSH: Oh gosh, I remember when I accepted the invitation from the National Science Foundation, my program officer said to me, "You know, it's going to be easier for us to get help to folks at the space station than it will be for us to get help to you guys when you finally reached Thwaites. Are you sure you still want to go?" And I was like, "Yeah, of course I want to go!" And [LAUGHS] I really had no idea how far away this place would be. It literally took us a month to arrive. We were on an icebreaker called the Nathaniel B. Palmer that set sail from Punta Arenas in Chile. And the Palmer's about the length of a football field, so you can walk it from end to end in under a minute. From southern Chile, we sailed out the Strait of Magellan, and then started to cross the Drake's Passage, which is considered the wildest, most predictably wild ocean in the world. Basically, it's kind of the choke point between South America and the Antarctic Peninsula. And so all of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current that swirls around Antarctica gets squeezed right there. And so you tend to get really heavy high seas and big storms. Our crossing was pretty eventful. We had regular sort of 25-foot swell. At one point, you know, like, a gigantic refrigerator in the lab became untethered from the ship and, like, slammed across the lab. And we had to, like, strap it back down. Most people got really horribly ill during our crossing. And then you get across the Drake's Passage, and then suddenly, you're in iceberg territory. Our ship, an icebreaker, is made to ride up on top of ice floe, which is relatively flat sea ice, and then it kind of causes the ice floe to crack beneath it. It's not made to like run into an iceberg. So then we had to cross a bunch of big sea ice fields for days. And right when we first arrived at Thwaites, we then had a medical emergency on board that caused us to have to reroute to Rothera Base for 10 days, and then come back. So it did take us a month to arrive, which was wild.

An iceberg drifting in the ocean as the Nathaniel B. Palmer makes its way to Thwaites glacier. (Photo: Elizabeth Rush)

CURWOOD: So given how difficult it is to get an expedition down to this part of the world, why were so many scientists keen to go there -- and writers, too?

RUSH: Thwaites really is considered ground zero for the possibility of accelerated sea level rise this century. And yet, I mean, no one in Earth's history before us had ever been to the place where the glacier discharges ice into the sea. So we don't know basic, basic things like, how warm is the water circulating beneath Thwaites? How strong are the currents pushing that water under the ice? So the reason Antarctica, and in particular, West Antarctic glaciers are so vulnerable to our changing climate is not because they're melting because of atmospheric warming. They're melting because there's this warm water that's circulating beneath them, eating away at the ice from below and causing it to become physically unstable, which just has the potential to give you a rate of retreat and collapse that outpaces significantly glacial retreat, as we normally think of it, where you have kind of atmospheric warming above causing the ice to melt. Thwaites is sort of like a house of cards. And we're concerned as we lose some of the base, or the underside of the glacier, you're taking cards out of that house, and you could cause it to become so unstable that the whole thing falls apart really quickly. And I think one last kind of nerdy thing that's useful to know is that, you know, we know from studying different geologic records that in Earth's history, let's say like 15,000 years ago, roughly, there were rapid pulses of water into the ocean that caused sea levels to rise 50 feet over a couple hundred years. These events are called meltwater pulse 1A and 1B. And the supposition is that a significant portion of the ice that's causing that rapid, accelerated sea level rise is coming from Antarctica. But no human beings have ever lived through or recorded those events. Like, we know that they happened, but we don't really know what caused them. We don't know the drivers or the mechanisms behind that change. And so I think in the scientific community, at this deep level, there's a question, like, if we lose Thwaites, are we in the meltwater pulse 1A territory? Are we thinking about a rapid acceleration of sea level rise that's not really in our models -- yet.

Thick ice floes often slowed the icebreaker’s progress. (Photo: Elizabeth Rush)

CURWOOD: Liz, take me to the moment that you first set eyes on Thwaites, it's in your book on page 200. Please set it up first.

RUSH: Yeah, so this is just a short passage that's really about the morning of our arrival. And it starts, I guess, a few hours before we arrive. And I remember this evening really well, and I remember almost feeling like a kid on Christmas. You know, when you wake up and you're like, Is it Christmas yet? And you're like, No, it's 11:15 at night, Okay, I gotta go back to bed. And then you wake up two hours later, and you're like, Is it Christmas yet? And you're like, okay, it's 1:12, and then you go back to bed. That was what this night was like for me. [READING] That night, sound sleep eludes me. I wake often, each time hopeful that we have arrived. Finally, around five o'clock I rise, shuffle up the four flights of stairs, undog the door by the ice tower and walk out onto the bridge wings. Thwaites' gray margin wobbles in the gloaming. We wind alongside, entering small coves and rounding odd promontories, our pace slow to hold this precarious line. The ice face soft as dunes. The night's new hint of darkness gives way to the bruised light of dawn, and many others appear to watch what each of us has been working towards, for weeks, for years, and in some cases, for decades, come into sharp focus. We don't talk. When someone wants to say something they whisper, as though we're in a giant, roofless cathedral. We, who have been at sea for so long, finally gaze upon the glacier that has already given us one another. Rick, the chief mate, stands attentive at the ship's helm, the captain next to him, steering us along the edges of Thwaites' unfathomable fracturing, its hemorrhaging heart of milk.

Penguins on an ice slab near Antarctica (Photo: Elizabeth Rush)

CURWOOD: Then soon, after navigating through previously unnavigable waters, there's a huge collapse of ice and you're witness to a radical and rapid change that happened almost just before your eyes. Tell me about that.

RUSH: Yeah, so we worked probably for about six days nonstop. When you're on one of these scientific missions, once you get to your field site, there's no off switch, the ship is really just cranking on all cylinders at all times. So we were doing science 24 hours a day for like six days nonstop. And then, suddenly, there were more icebergs in the bay; suddenly, the waters became a lot less easy to navigate. And everyone was sort of wondering what had happened or what had changed. And it turns out that, you know, a piece of Thwaites like 25 miles wide and 15 miles deep had literally broken apart alongside us and was basically discharging these massive icebergs into the very bay that we were sailing in. And I can remember seeing these, we got these aerial satellite images of our study area. And indeed it looked, you know, this ice shelf was solid one day and the next day it looked sort of like a belligerent teenager had, like, taken a baseball bat to a car windshield and shattered it into hundreds of pieces. And I saw those and I literally just ran up to the top deck to try to see this process unfolding right in front of me. And I stood up there for hours. And on the one hand, part of me when I saw that was like, "This is why we're here, right? Like, man, we're getting, like, we are really getting the right data right now. This will be really useful”. And then that's coupled with a, you know, a deep sense of, “what I wouldn't give for none of this to be happening. What I wouldn't give for this to not be falling apart in front of me." And the bizarre thing was that it was actually like the most, one of the most beautiful days of our expedition. The sun had finally come out, the air was, like, crisp and cold. And all of a sudden, there were these like lavender-faceted icebergs in the bay, and I could only see them as icebergs, I could only see them, you know, for the first time, not, not a sign of significant change. So I stood up there for many hours and kind of tried to witness what was happening. And I felt like I always fell a little short of being able to, to actually perceive it.

As the Palmer made its way along Antarctica’s frozen, rocky edge, penguins and other wildlife came into view. (Photo: Elizabeth Rush)

CURWOOD: So of course, this was a journey for you, Liz, in understanding life, motherhood, our place on the planet. And for the scientists, there was a lot of data for them to gather. What were the big scientific takeaways from this expedition, do you think, to Thwaites?

RUSH: Well, I think of a couple. One of the most significant things that we were able to accomplish when we were at Thwaites is that we sent a submarine beneath the ice shelf. And that submarine was able to give us some really important information about the temperature of the water circulating beneath Thwaites. The most significant finding there was that the water beneath Thwaites is actually a little bit cooler than scientists had calculated. And I think folks tend to want to celebrate that, it's like, "oh, the water's cooler, that's so great!" But just because the water is cooler, doesn't mean that the glacier is moving any less quickly. In fact, the glacier's deteriorating at the same rate, and its water that's not as warm that's causing that deterioration. So in many ways, this proves that the ice shelf itself is actually more physically vulnerable than we had been calculating. The other really significant findings from that submarine was that it also drew very close to the seafloor and created these incredibly detailed sonar images of the seafloor. And from them, one of the sedimentologists on board was basically able to reconstruct the retreat of Thwaites during a really significant event that happened sometime in the last two centuries. He basically kind of read the ridges on the seafloor. Through that information, he was able to calculate a maximum rate of retreat for Thwaites that is two to three times faster than we had previously calculated.

After a month of travel through stormy seas, thick sea ice and iceberg territory, the Palmer finally arrived at its destination, Thwaites glacier. (Photo: Elizabeth Rush)

CURWOOD: Before you go Liz, talk to me about the strong thread of community that's, that's in your book. You have scientists and crew working around the clock, cooking, measuring, fixing, surviving, I guess, a nail-biting medevac. I mean, that, can't tell the whole story here. But that was quite a, it took, A, a lot of time and B, it was rather harrowing.

RUSH: Yeah.

CURWOOD: Later on, we feel that you're surrounded by support as you bring your son into this world. How did you witness community on the ship? And how does that influence how you see this world working together on the climate dilemma?

Fractures permeate Thwaites’ edge, soon to calve new icebergs. (Photo: Elizabeth Rush)

RUSH: You know, so we were, there were 57 of us on board this boat. And we came from all over the planet. We're from the Philippines, from Brazil, from Sweden, from the US. And we had this seemingly sort of impossible task, which was gathering information about this place that no one has ever been able to even reach before. And that we were able to do that, sort of, while existing inside of one of the most, you know, extreme environments on the planet, to me, was an absolute testament of what is possible when you work together with other human beings. In the climate conversation, it seems to me like there's been a bit of a shift in the past couple years, away from the kind of blame game narrative where you're an individual consumer and your decisions about organic or non-organic tomatoes, and cardboard packaging and plastic packaging is really where your, your impact on the climate crisis is going to be most profoundly felt. It seems to me like we're moving away from that, towards this idea that real climate action is going to be collectively achieved. But I don't think we have a lot of good stories that do justice to the ways that communities come together and are formed around shared concerns.

Elizabeth Rush is the author of The Quickening and Rising: Dispatches from the New American Shore, a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. She teaches at Brown University. (Photo: Stephanie Ewens)

And so one of my goals in writing this book was really to try to create a narrative that is not just about my singular expedition, but more about this community and the way they came together. So the book also has a pretty unconventional format in that, I don't know, about 50% of it is narrated in my first person, but my first person is regularly interrupted by the voices of my shipmates, and they're talking about their experiences on board. So if you were to flip open The Quickening, it kind of looks like a screenplay half the time. And I think it's important to know that what they say is, like, literally what they said on the boat. So I conducted 213 interviews while on board, and I hand-transcribed them all to create the archive that would, like, build the backbone of this story. And so it's my hope, really, that the book can be sort of like an experiment in storytelling that highlights collective labor. And it definitely, I mean, it definitely made me come home and think about how often I feel powerless in the face of the scale of the climate crisis. But when I feel that, I realize I have tools for combating that kind of desperation. And so for me, that's meant becoming much more involved in community organizing around just climate adaptation in Rhode Island. Any kind of collective climate action beyond the individual, I think, is, is where our power really resides.

O’NEILL: That’s Elizabeth Rush, Professor at Brown University and author of The Quickening: Creation and Community at the Ends of the Earth speaking with Living on Earth Host Steve Curwood.

Related links:

- Find a copy of The Quickening (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

- About author Elizabeth Rush

- Learn more about scientific research on Thwaites Glacier

- Listen to LOE’s interview with Elizabeth Rush about her previous book Rising

[MUSIC: John Butler, “Ocean” Single, Family Music Pty Ltd]

O’NEILL: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Quentin Bell, Paloma Beltran, Josh Croom, Karen Elterman, Swayam Gagneja, Sommer Heyman, Mattie Hibbs, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Sarah Mahaney, Sophia Pandelidis, Caitlin Quirk, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments at loe dot org. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth