February 9, 2024

Air Date: February 9, 2024

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Green Cooling and Heating for Public Housing

View the page for this story

To help address the climate crisis the city of Boston is piloting the replacement of natural gas with ground-source heat pumps in a public housing project. The technology brings fossil-free cooling and heating as well as cleaner air to historically disadvantaged tenants. Host Jenni Doering speaks with Kenzie Bok, the Administrator of the Boston Housing Authority. (12:10)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Living on Earth Contributor Peter Dykstra joins Host Steve Curwood with news of a reprieve -- for now -- for the drinking water supplies threatened by saltwater intrusion in coastal Louisiana. Also, a city in Germany is using the Rhine River as a giant source of heat and cooling potential on an industrial scale. And in history, they mark the birthday and exoneration of the Renaissance’s Galileo Galilei. (04:35)

Coming Cleaner on Fracking Chemicals

View the page for this story

Pennsylvania has advanced rules that will warn the public about toxic chemicals gas and oil drillers plan to inject into the ground, but chemicals that are considered “trade secrets” will remain shrouded in mystery. Environmental Health News reporter Kristina Marusic joined Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill to unpack what the new fracking rules mean for keeping drinking water safe. (07:00)

Ice Skating on the Rideau Canal

/ Bob CartyView the page for this story

The warmer winters of climate disruption is bringing shorter and shorter skating seasons on the Rideau Canal in Ottawa, Canada. We head into the Living on Earth archives for a taste of days gone by, when reporter Bob Carty hit the ice to meet locals enjoying the serenity of a skate along the canal. (07:35)

Journeys to the Depths of the Ocean

View the page for this story

The oceans cover 70 percent of our “blue planet” yet remain largely unexplored because of the intense pressures at depth. But there are some intrepid few who have descended into this “underworld” and lived to tell of its marvels, and journalist Susan Casey profiles them in her latest book. She joins Host Steve Curwood to talk about The Underworld: Journeys to the Depths of the Ocean. (14:32)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

240209 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Kenzie Bok, Susan Casey, Kristina Marusic

REPORTERS: Bob Carty, Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

A new geothermal project will help keep low-income Bostonians warm in the winter and cool in the summer.

BOK: All of our public housing developments are environmental justice communities. And the reality is, is that if we weren't intentional about this, because public housing has been historically disinvested in, and because we have very old buildings which require a lot of updating for a fossil fuel transition, they would naturally fall to the back of the line. And here we're doing exactly the opposite.

CURWOOD: Also, what it’s like to dive miles beneath the surface of the ocean.

CASEY: To go into the underworld, it’s the hero’s journey. It’s, you’re going down there and it’s not an easy journey. At the bottom of the Mariana Trench, for example, you’re going to have 16,000 pounds of pressure per square inch. So there are rules that you have to adhere to, to be able to make this journey.

CURWOOD: Those stories and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Green Cooling and Heating for Public Housing

The Franklin Field Apartments in Dorchester, MA will be the first apartment complex in Boston to run on networked geothermal heat pumps. (Photo: John Wilcox, Courtesy of City of Boston Mayor’s Office)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

One of the biggest inequities when it comes to environmental injustice is the heat island effect in cities, where it can be as much as ten degrees hotter during heat waves than in nearby leafy suburbs. BIPOC people in the US tend to be concentrated in center cities, and sweltering summer heat can be especially pronounced in the concrete jungles of housing projects erected for disadvantaged people starting back in the Depression. But now, as part of an effort to decarbonize, the city of Boston is piloting ground-coupled heat pumps in public housing to cool and heat. Using a looped system of pipes filled with water or other liquid, geothermal or ground source heat pumps harvest the 50 to 60 degrees Fahrenheit warmth from down below in the winter and dump excess heat underground in the summer. That process does take some electricity, but if it’s from solar or wind, heating and cooling buildings can be entirely fossil fuel free. That’s the ultimate promise of geothermal projects like the one being piloted at Franklin Field Apartments in the city of Boston, which is led by Mayor Michelle Wu.

WU: This is a demonstration of just how much is possible when we collaborate on ambitious solutions that intersect with our greatest challenges, and when we refuse to choose between those false choices of either the climate crisis or the housing crisis, and instead realizing that they are both one and the same and interconnected.

DOERING: The Boston Housing Authority hopes to have the geothermal system up and running by the fall of 2025. Kenzie Bok is the administrator for the BHA. Welcome to Living on Earth!

BOK: Thank you so much. Thrilled to be here.

DOERING: So paint a picture for me please of what this geothermal project will actually look like. What's the vision here?

Kenzie Bok (left) is the Administrator for the Boston Housing Authority, which is partnering with National Grid to complete the project. Here she stands with Boston Mayor Michelle Wu (right) at the announcement of the project. (Photo: Isabel Leon, Courtesy of City of Boston Mayor’s Office)

BOK: We're incredibly excited about the opportunity to make a public housing development in Boston, Franklin Field, the first neighborhood in Boston to be powered by geothermal. So this is a site we have with 450 families living. This first phase is going to be 129 families. They live across seven buildings that right now are powered by a very old-fashioned central natural gas boiler system. And we were going to replace that boiler with more natural gas a few years back, that was the plan. But then Mayor Wu announced our intention, the BHA's plan, to go fossil fuel free. And we said, well, the first step to going fossil fuel free is not adding new fossil fuel infrastructure. And so we started having to come up with an alternative plan for how we're going to heat these buildings. And initially, it was air source heat pumps, and now it's actually going to be powered by the earth, with geothermal heat pumps. And it's going to mean for the first time, our public housing residents have cooling in their units in addition to heating. So it's really exciting for us.

DOERING: So you know, we're seeing hotter and hotter temperatures in the summer in Boston and around the country and around the world. So you're saying that these residents didn't have air conditioning before?

BOK: That's right. Because of the historically moderate climate, public housing is not actually required to have air conditioning in New England. And so it wasn't built into the specs of these buildings. Now, over recent years, people have often had window air conditioners in their units, but the way the units are built, you have to have a separate window air conditioner in for practically every room in order to cool it appropriately. And you know, that's really inefficient, it can be expensive to acquire those units. There's a lot of disadvantages to that approach. And we're really excited that we're going to be able to really give them state-of-the-art in-unit cooling now for the first time.

DOERING: So give me the big picture here about why you and the Boston Housing Authority are really excited about this project at Franklin Field Apartments.

Boston Mayor Michelle Wu (left) has set a target for the Boston Housing Authority to be fossil fuel free by 2030. Here, she poses with a Franklin Field Apartment tenant (right) for a photo. (Photo: Isabel Leon, Courtesy of City of Boston Mayor’s Office)

BOK: We feel like there's hugely multilayered benefits. So we're actually doing a bunch of electrical and HVAC work as part of the project, and a critical piece is we're actually replacing the old gas stoves in the units with new electric induction stoves, and we're going to be adding mechanical ventilation. So it's both going to bring better air quality, a better experience for our residents who live in the units, it's going to bring jobs to this area. And we actually, the Housing Authority, has historic partnerships with helping to get our public housing and voucher residents into jobs like high quality jobs in the construction trades. And we see geothermal as a space where there could be a lot of those jobs. And I think that everybody wants to see us combat climate change. I mean, Franklin Field is a site where even though it's not right on the coast, it actually has repeatedly been subject to flooding because of groundwater changes. And then you've also got heat island effects in that neighborhood where the in-unit cooling can't come fast enough. So I think everybody sees climate change coming. And the question is like, what do we do with that? And how are we not fatalistic? And I think us getting to do this exciting installation right here in a public housing community, it gives everybody in our community a lot of hope, and a real sense of being at the heart and right at the frontier of that change.

DOERING: Tell me more about this goal for the Boston Housing Authority to be fossil fuel free by 2030. And can you tell me about how this project helps get Boston closer to that goal?

The project plans to provide heating and cooling across 7 buildings and 129 public housing units. Shown here is Mayor Michelle Wu (far left), U.S. EPA Administrator Michael Regan (next left), Massachusetts Governor Maura Healey (center), and Kenzie Bok (far right) among various tenants of the Franklin Field Apartments. (Photo: John Wilcox, Courtesy of City of Boston Mayor’s Office)

BOK: Yeah, so we're the largest landlord in Boston. We own about 10,000 units of housing. And we house many of the lowest income Bostonians, and we're really proud of that. And what we're doubly proud of is that with this fossil fuel free goal, we're really putting our public housing residents at the front of the line in the energy transition. So you know, we talk a lot about environmental justice communities, all of our public housing developments are environmental justice communities. And the reality is, is that if we weren't intentional about this, what you would see is that, because public housing has been historically disinvested in and because we have very old buildings with creaky systems, which require a lot of updating for a fossil fuel transition, they would naturally fall to the back of the line. And here, we're doing exactly the opposite. We really think it's vital that we take the energy transformation and really intertwine it with improving conditions for all our public housing residents.

DOERING: And how do you plan on involving residents of Franklin Field in this process?

BOK: Yeah, so our resident leadership at Franklin Field is amazing. It's a heavily Latino site. And so we have a lot of Latino leaders there. And they're really excited about this. And a lot of the reason that we're doing this here is hearing about some of the air quality challenges at Franklin Field and recognizing that we couldn't possibly do an energy transformation there without also tackling ventilation. We know that our residents suffer disproportionately from asthma, so they've been big advocates for that. They also are, you know, really excited about the job possibilities. They're always pushing for more opportunities for the youth at the site. And we actually have a new big youth program kicking off at Franklin Field that's been funded by Mayor Wu. And there's a workforce development component of it. So we're really interested in, can we get our young people coming in, like seeing this geothermal installation go in, and then open up pathways for them to be future workers, if that's something that excites them. So we see our residents as co-creators of their communities and environments. And so this has been something where every step along the way we've been, we've been talking to them about it.

DOERING: So talk to me a little bit more about how this project might advance environmental justice efforts, you know, here in Boston and beyond and help sort of push things forward in the country.

The project will also replace gas stoves in these public housing homes with new electric induction stoves, which aims to improve air quality and health outcomes for residents. (Photo: rhodesj, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BOK: We think that there are huge advantages to doing geothermal first in public housing. They're both moral and values advantages, putting the communities that have too often been hurt by environmental pollution, and all the kind of negative environmental decisions that our communities have made, putting them at the front of the line for change, for cleaner air, for more comfortable living, that just feels morally important. It's also true that a public housing authority like ours has the advantage where we own a whole bunch of buildings all together. So when you're testing out the mechanism for putting a whole neighborhood on a new source like geothermal, it's actually easier to do it with us than a neighborhood that's split up between lots of different owners. So we see that as a kind of logistical advantage to doing what we should be doing from a values perspective anyways. So we think that if we can do this here at Franklin Field, then we can partner with the utilities, with National Grid and others to do this across all of our sites. So you know, we would love to see this expand to other sites of ours. And then we think that as everybody gets kind of comfortable with this technology, it's going to expand to other neighborhoods in the city, and also everywhere else in the country. You know, we think it would be great if suddenly a bunch of utilities said, "Oh, wait, public housing, that's a great place to start with this transformation." And this sort of Boston-driven focus on putting our public housing residents first became something that was happening all over the country. We think that'd be great.

DOERING: So you've got National Grid involved in this geothermal project, but they're not going to be selling gas to residents or to the Boston Housing Authority anymore. How does that sort of change things? And why are they on board with, you know, giving up a revenue stream?

BOK: I think that for them, it's really exciting to think about a system that they could install and manage the same way that they do kind of existing fossil fuel infrastructure, and there will be a continuing revenue stream for geothermal. It will obviously look different. But I think that for the utilities, the opportunity to have a networked solution is actually more similar to what they've been doing, than some of the other alternatives. You know, there's a lot of solutions that work for one house somewhere, but they don't work for getting a whole city like Boston off of fossil fuel infrastructure. And so we actually think seeing the utilities as a partner in this, rather than as an obstacle, is really critical for us getting to that systems-level approach, and we're excited that they're willing to be that kind of partner.

Residents of Franklin Field Apartments attended the announcement of the project in January. Here they pose for a photo with Boston Mayor Michelle Wu (center). (Photo: Isabel Leon, Courtesy of City of Boston Mayor’s Office)

DOERING: Now switching to geothermal is kind of a first step that we can take towards decarbonization in buildings. What's the next step in Franklin Field Apartments and in the Boston Housing Authority as a whole?

BOK: Yeah, so we know that to really do this well, we have to kind of change all of our systems. So in this case, you know, we're putting geothermal in, but we're also putting updated electrical and HVAC in at the same time, so that the geothermal hyperefficient system can hook up to better infrastructure inside of our buildings. We're also, as we do that additional electrical wiring, looking to ready our buildings for solar on top of the roofs, right? In the long run, I'd love to see Franklin Field actually be a net energy producer, between the geothermal in the ground and solar on the roofs. So we're getting more and more ambitious about this all the time.

DOERING: So how do you actually make this work? I mean, if you're talking about, you know, making a change that's already pretty significant, and then looking even bigger picture and saying, "Well, wait a minute, we need to make sure that the electrical system is going to maybe be able to handle solar panels someday." So how do you make this work with a limited budget?

BOK: The financial support that we're getting from both Mayor Wu at the city of Boston and from the federal government, especially some of the money that's contained within the Inflation Reduction Act, is totally crucial. So you know, there's a lot of tax credits in the Inflation Reduction Act, and for the first time, public institutions like ours are able to take advantage of them, but there's also just funding. You know, we had the EPA Administrator at this site talking about the grants that they're making available for building decarbonization. These are the Climate Pollution Reduction Grants. You know, that's the type of funding that we're going to need. And then the mayor's put really significant funds in the capital budget for the city to support us. So there's no question that this takes money. What we've noticed is that the incentive programs that do exist, both the Mass Saves program at the state and some of the federal incentives, we actually get more money to fund these projects when we go bigger, when we think more about a like holistic deep energy retrofit. So that's really the direction that we're driving things in. And, not for nothing, the world can't wait, right? The timing of climate change is such that we all need to be looking for ways to do the most ambitious projects possible, because we can't stretch this all out over multiple decades.

DOERING: Kenzie Bok is the Administrator for the Boston Housing Authority and former Boston City Councilor for District 8. Thank you so much.

BOK: Thanks so much for having me.

Related links:

- Boston Housing Authority | “Mayor Michelle Wu Announces Agreement Between Boston Housing Authority and National Grid to Develop Networked Geothermal Heating at Franklin Field Apartments”

- Dorchester Reporter | “Franklin Field Complex Will Be Outfitted With Geothermal Heating, Cooling Technology”

- Boston Globe | “Heating at Franklin Field in Dorchester to Be Converted to Geothermal.”

- Read more about the Boston Housing Authority

- Learn more about geothermal heat pumps.

[MUSIC: Joe Sample, “Night Flight” on Joe Sample-Sample This, by Joe Sample, Warner Records]

DOERING: Coming up, unwrapping the secrecy around fracking chemicals in Pennsylvania. That’s just ahead. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Joe Sample, “Night Flight” on Joe Sample-Sample This, by Joe Sample, Warner Records]

Beyond the Headlines

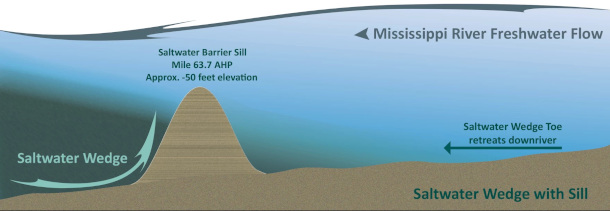

A graphic depicting what a saltwater wedge looks like, how it interacts with freshwater, as well as the sill, or underwater barrier, constructed by the Corps in July 2023. (Photo: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I'm Steve Curwood.

On the line now from Atlanta, Georgia is Peter Dykstra, who takes a look beyond the headlines for us. Hey, Peter, how you been? What's going on down there in Georgia?

DYKSTRA: Well, I've been well, Steve. Topic number one is going to be over in Louisiana, there was a problem with saltwater intrusion threatening drinking water, even in the big cities like New Orleans. Saltwater intrusion happens when there are low levels of freshwater and the saltwater essentially gets into drinking water systems, but that threat is off for now. There was a very, very dry period upstream in the Ohio River, the Mississippi River, and that was threatening for saltwater to come into the drinking water intakes throughout Louisiana. But lately, there's been a very wet, rainy, snowy period and that's postponed the threat.

CURWOOD: So I imagine that Louisiana's guarantee for sweetwater is somewhat limited, and this is a big problem around the world.

DYKSTRA: It's a big problem and a little bit different than the situation in Louisiana, which was caused by temporary drought followed by temporary heavy rainfall. In places like Bangladesh, it's a more permanent and relentless thing. You've got not only higher demand for freshwater, in very marshy, low-lying areas, but the other problem is sea level rise. The oceans and the saltwater levels are getting higher. When those things collide, you could have a food crisis in areas where the freshwater supply is contaminated and you can no longer grow crops.

CURWOOD: Another reason to pay attention to the threat of climate disruption with the rising sea levels.

DYKSTRA: One more.

CURWOOD: One more. Hey, Peter, I understand you have some good news for us about heat pumps. We just talked about a pilot project in Boston in public housing. What's the story you have?

Millions of liters of water flow through the lower Rhine River in Europe daily. Engineers at MVV Umwelt GmbH plan to harness that energy using heat pumps, potentially supplying heat to thousands of homes in the city of Mannheim, Germany. (Photo: Marco Verch. Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DYKSTRA: We're looking at Germany, particularly the city of Mannheim, along the Rhine River. Heat pumps have been in use throughout Europe in much greater extent than in the US. Germany has about 2 million heat pumps, some drawing heat energy from the air, some drawing heat energy from the ground. Mannheim and other cities are looking at repeating this on an industrial scale by drawing heat out of rivers like the Rhine and using it to heat not only homes but larger businesses, to take the heat, pardon the pun, off of other sources like coal and natural gas.

CURWOOD: And how big a deal is this? I mean, how much heat is there in the river going by there?

DYKSTRA: Well, a project manager named Felix Hack says that in the city of Mannheim, the thermal energy could help heat homes many times over. They are hoping that it can be a real weapon in the fight against climate change.

CURWOOD: Okay, Peter, this is the part of our discussions where you open the history books, you take a look. And I think this week, maybe you have a bit of a telescope to look back?

Galileo Galilei was an Italian mathematician, philosopher and astronomer, who was appointed court mathematician to the Medici dukes of Tuscany at Florence in 1610. (Photo: Royal Museums Greenwich, Wikimedia Commons, Fair Use)

DYKSTRA: A long way back. February 15, 1564. Born in Pisa, Italy, is Galileo, who became a famous astronomer, physicist, and for a while in the Catholic Church, heretic, by moving forward the theory that the Earth revolves around the sun, and not the other way around. The official heresy label came in 1633.

CURWOOD: Eventually, though the Church recanted, if I can use that word.

DYKSTRA: They did. They apologized to Galileo, and it took only 359 more trips around the sun when Pope John Paul the second acknowledged the error and declared ‘my bad’ on behalf of the Church.

CURWOOD: Uh, Peter, wasn't that in Latin?

DYKSTRA: Oh, yeah, mea culpa.

CURWOOD: Thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is a contributor from Atlanta, Georgia, and we'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Well, thank you, Steve. Good to talk to you. We'll do it again soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth webpage. That's loe.org.

Related links:

- NOLA | “Saltwater Intrusion Threat to Southeast Louisiana Is Over — at Least for Now.”

- Nature and Environment | “Could Large Heat Pumps Revolutionize How We Warm Our Homes?”

- Learn more about the Galileo Project

[MUSIC: Christopher Wilson, lute, “Calata ala Spagnola” on Early Venetian Music, by Vincenzo Capirola, Naxos]

Coming Cleaner on Fracking Chemicals

Workers at a fracking drill site in Murphy, Pennsylvania. In 2024, Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro announced changes in policy that will require fracking companies to disclose lists of chemicals they plan to use before they break ground on new drilling sites. (Photo by Alice McGown, FracTracker Alliance, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: Back in November 2023, Environmental Health News reporter Kristina Marusic talked with us about the bid by the Democratic Governor of Pennsylvania, Josh Shapiro, to unmask the secret chemicals used in hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking,” though some details were lacking. Now the state has advanced rules that would require gas and oil drillers to disclose any toxic chemicals they plan to inject into the ground, rather than only requiring them to tell regulators after the fact. But some chemicals will remain shrouded in mystery, since those that are considered “trade secrets” are exempted, and the new rule only applies to new fracking operations, not existing projects. Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill got an update from reporter Kristina Marusic about what the new fracking rules mean for keeping drinking water safe.

MARUSIC: So the big changes with this new policy are that now every single company that wants to drill a well in the state of Pennsylvania will have to submit a list of the chemicals they intend to use to the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection before they drill the well, as opposed to after, and the Department of Environmental Protection is now going to post those lists on its own website and make them publicly available before drilling happens.

O'NEILL: So, increased transparency is the goal, and they're going to publicly post these lists. What does that mean for the people in these communities? What can they do with these lists of chemicals now that they are going to be disclosed?

MARUSIC: This theoretically might give communities more of an opportunity to say, “We're not comfortable with these chemicals being used to drill a well in our community,” and to either use that during, like, public hearings about the permitting process, or to negotiate with an oil and gas company or ask an oil and gas company to change the mixtures of chemicals that they're using. There's no guarantee that that would be effective, of course, but I do think, in general, it's helpful for communities to know what chemicals a fracking company is proposing to use in wells that they want to drill near their homes and schools and businesses.

O'NEILL: Kristina, please remind our listeners, what are the concerns with fracking when it comes to chemical exposure?

Fracking companies will still be allowed to keep secret from the public their chemical mixtures that are considered “proprietary”, though these will need to be disclosed to the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection. (Photo: Ted Auch, FracTracker Alliance, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

MARUSIC: There are more than a thousand different chemicals that have been used in these fracking fluid mixtures over the years. And these chemicals can include carcinogens like formaldehyde, arsenic and benzene, possible carcinogens, things like naphthalene and acrylamide, and ethylene glycol, which is linked to damage to the kidneys and the nerves and the respiratory system. We also know that PFAS or forever chemicals have been used in fracking in various parts of the country, including Pennsylvania. And the concern is that, you know, communities may be exposed to these chemicals through the process of fracking. There's a specific federal loophole called the Halliburton Loophole that exempts the oil and gas industry from federal regulation under the Safe Drinking Water Act. And this means that the industry can use hazardous chemicals like these without being subject to the same regulations as other industries that want to use these types of chemicals. I wrote about a 2023 study that found that fracking companies used more than 280 million pounds of hazardous chemicals from 2014 to 2021 that should have been regulated under the Safe Drinking Water Act, but weren't because of this Halliburton Loophole.

O'NEILL: And so Governor Shapiro's announcement means that there's, you know, a step being taken towards increased transparency. But from what I understand, this new policy does not cover chemicals that are considered trade secrets. What's the trouble there?

MARUSIC: That's right. So in Pennsylvania, and lots of other states where there's a big oil and gas presence, a lot of the public disclosure laws for these chemicals have a trade secrets provision that allows companies to withhold information about chemical mixtures that they say are proprietary, or that constitute trade secrets. And there was another study last year that showed that the number of times and the quantities of chemicals that companies are claiming are trade secrets in their public chemical disclosures has increased pretty dramatically over time, which some people find concerning. And this new policy still allows for companies to withhold that information from the public. In Pennsylvania, companies have always been required to provide that information to state regulators if they ask for it. So while that information won't be included in the public disclosures, in theory, the Department of Environmental Protection should get the complete list including those trade secret chemicals. But one problem with that is that operators buy these mixtures of chemicals from third parties. One of the companies that sells the most of this stuff is Halliburton, with the same name as the Halliburton Loophole. And they're called things like 'Frack Magic'. They have, like, very goofy names, these fracking chemical mixtures. And they don't always come with complete ingredient lists, because they're not required to by law. So in a lot of instances, operators don't actually know what's in these fracking chemical mixtures. So they're not able to provide a complete list to regulators. And in Pennsylvania, the law specifically says that they can't get in trouble for not disclosing a complete list if it's because they don't have it. So there's this kind of lack of transparency all throughout the supply chain that causes problems.

Kristina Marusic covers environmental health and justice issues in Pittsburgh and Western Pennsylvania for Environmental Health News. She is also the author of "A New War on Cancer: The Unlikely Heroes Revolutionizing Prevention". (Photo: Courtesy of Kristina Marusic)

O'NEILL: So now that this new policy is taking effect, what repercussions would fracking companies face if they don't abide by the policy, if they don't make these chemical lists available to the public?

MARUSIC: The Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection says it's actively providing training to fracking operators on these new rules, and that it plans to review all of these documents before drilling happens to make sure that this information has been provided. The agency didn't directly respond to my questions about whether drilling permits could be denied if companies didn't provide this information, but they did say that the agency will conduct enforcement as needed to ensure compliance with these new rules. And in general, the agency's enforcement tools typically include notices about violations and kind of ongoing communication with fracking companies about coming into compliance. And if that's not effective, they can ultimately fine a company for not adhering to its policies.

DOERING: That’s Environmental Health News reporter Kristina Marusic, speaking with Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill.

Related links:

- Kristina Marusic’s Website

- Read the statement on fracking from Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro’s administration.

[MUSIC: ARTEMIS, “Bow and Arrow” on In Real Time, Blue Note Records]

Ice Skating on the Rideau Canal

Winterlude Festival on the canal in Ottawa (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: Perhaps the biggest skating rink in the world is one of the many casualties of climate disruption. In downtown Ottawa, Canada, the Rideau Canal usually turns into a skateway each winter. But the winter of 22-23 was one of the warmest on record for Ottawa, and the ice never got thick enough to be deemed safe for skating. And in 2024 it opened for just four days in January before having to shut down again. For a taste of days gone by, we’d like to share this piece from 2013, when veteran broadcaster Bob Carty hit the ice.

[TRAFFIC COMMUTE]

[RADIO ANNOUNCER: “CURRENTLY IN OTTAWA IT’S AROUND 16 DEGREES...]

CARTY: Rush hour in Ottawa on a cold March morning. So cold you have to scrape the frost off the inside of the car windows. So cold your tires have frozen flat on the bottom, and until they warm up you get a bumpy ride, what Canadians call having square tires. And then there's the slippery streets, the snow banks, and the slush.

[RADIO ANNOUNCER: “...AND ANOTHER ACCIDENT. WE’RE UP TO 6 NOW...”]

CARTY: In Ottawa, where winter is a five-month affair, there is at least an alternative to the morning madness of rush hour. Instead of the expressway, you can take the skateway.

[PHONE RINGS]

[RECORDED VOICE: “RIDEAU CANAL CONDITIONS AT 8:30 A.M. THE ICE SURFACE CONDITIONS ARE GOOD FROM THE NATIONAL ARTS CENTER TO PATTERSON CREEK...”]

[SKATES ON ICE]

MAN 1: Early in the morning, when the sun comes up, and there's hardly anybody on the canal and you can just hear your skates, it's about the only thing you can hear. It's wonderful.

WOMAN 1: I haven't skated for years. I skated when I was a kid, and it's great to be able to skate again, and it's just so much fun skating to work. I just think it's incredible. This frozen Rideau Canal is like a wonder of the world.

Winterlude Festival on the canal in Ottawa (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

CARTY: For two-and-a-half months, from late December to the usual mid-March thaw, an old canal running through Ottawa becomes the world's largest skating rink. It's 15 yards wide in most places. On one side students head south towards the University. On the other side, some neighbors and I are heading downtown with backpacks and briefcases. It's a three-and-a-half-mile commute for me, a 20-minute skate on a good day.

MAN 2: There's a few little bumps, but otherwise it's just really smooth and clear. The best part would be just at the beginning here, when you're sort of on the ice, just between the two walls of the canal.

WOMAN 2: What's interesting for me, being able to look at the sides of the canal, is that my ancestors were Irish stone masons who were brought over to work on the canal. The canal was built by Colonel By in 1832, and it was to give Canadians a route so they could avoid being ambushed by Americans on the St. Lawrence River. It's an amazing engineering feat.

CARTY: And there's another engineering feat just in keeping the skateway in operation every day. It takes 40 full-time employees, and a fleet of snow blowers, plows, and tractor-mounted sweepers, to clean off the snow and the ice shavings. Then, every other night, workers drill holes through the ice to pump up water to flood the surface. It's the equivalent of flooding 125 end-to-end hockey rinks. It takes eight hours. The result is a clean, smooth surface. Almost. You do have to watch out for the occasional rut. And the choice of skates is critical.

WOMAN 3: This took me a long time to get it straight about what kind of skates. I tried the new plastic molded skates that have Velcro snaps, and they're supposed to be really quick to put on. But I hated the feel of them. Then I tried the traditional women's fancy skates with the picks. Didn't like them, and so I now am the proud owner of my first pair of men's hockey skates, and they're great.

CARTY: Hockey skates are my choice, too. Though the new fad on the skateway are speed skates, the ones with long 14-inch blades, worn by men and women in spandex outfits who torque by you as you're struggling against the headwind. [GASPS] Did I mention the wind? It can turn a pleasant, just below freezing temperature into a wind chill that feels like 15 degrees below zero. Doesn't seem to bother some skateway commuters, though I have a personal rule of thumb: If your nostril hair freezes in the first minute, maybe it's too cold to skate today, even if you do have the appropriate apparel, such as some or all of the following.

WOMAN 4: Scarves and a “toque,” mitts, long underwear.

MAN 3: Fairly light shell jacket and a sweater. Shirt and tie. And the trick is not to get too sweaty on the way to work.

WOMAN 5: I, for one, need knee pads. [LAUGHS]

WOMAN 6: As you can see, I got on a really ugly hat that keeps me warm. And you need Kleenex in your pocket.

WOMAN 7: You need to have Kleenex in your pocket for two reasons. One, you need to be able to blow your nose, because it gets cold and then you go into the warmth. The second reason is to wipe off your skate blades when you're finished.

[CHILDREN TALKING, SKATING]

CARTY: After the morning rush hour, the skateway is taken over by others - children and their teachers on a school outing, pairs of mothers, on skates, pushing strollers, reckless teenagers bobbing in between tentative tourists who are trying not to break any bones.

[SKATES SWOOSHING]

WOMAN 8: The amazing thing is, on a beautiful Saturday or Sunday, to see thousands and thousands of people on this canal walking, pushing their kids in these little sleighs. And you see people who are new to Canada, who are valiantly trying to skate and kind of staggering along, and it's great.

[SKATING ON ICE]

CARTY: At the end of the day, the commuters reappear on the skateway, a bit rubbery in the legs. Which sometimes requires a brief stop for rest and refreshment at one of the outdoor eateries on the canal.

CLERK AT COUNTER: How are you? What can I get for you?

CUSTOMER: One orange juice, one hot chocolate, and a famous beaver tail.

CARTY: Yes, you heard it right. He ordered a beaver tail. What exactly is a beaver tail?

CUSTOMER 2: It's really a flat, long, dough-like pastry thing, and this one has garlic butter and cheese on it, so it's almost like a mini-pizza. But you can get just plain cinnamon and sugar, and even if you want some jams on top, you can do that, too.

Ottawa skaters (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

[SKATES ON ICE]

CARTY: Recharged and refreshed, the final mile home is like skating downhill. The wind is gone. The stars are coming out. Skateway commuters can give you sound ecological arguments for doing this: it saves fossil fuels, it reduces pollution, it lessens the risk of climate change. But frankly, the real reason is that it just feels good. As one 7-year-old put it, you don't have to go around in circles. It's fun to skate straight. For Living on Earth, I'm Bob Carty, skating straight on the Rideau Canal in Ottawa, Canada.

[MUSIC: Paul Winter “Wolf Eyes” from Common ground (A&M Records 1977)]

CURWOOD: We first aired this piece back in 2013. The following year Bob Carty passed away after an award-winning career with the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation and producing many fine stories for Living on Earth. We miss him and his great gifts in audio and reporting.

Related links:

- Ottawa Citizen | “Big void left by the closure of the Rideau Canal Skateway”

- CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation) remembers Bob Carty

- More about Bob Carty and his music

[MUSIC: Paul Winter “Wolf Eyes” from Common ground (A&M Records 1977)]

DOERING: Coming up, we go down… way down. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Along Came Betty, “Smoke & Mirrors” on The Secret Parts of Fortune, by Biff Smith, published by Along Came Betty]

Journeys to the Depths of the Ocean

The Underworld: Journeys to the Depths of the Ocean is Susan Casey’s latest book. (Image: Courtesy of Susan Casey)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Seen from space, ours is a blue planet thanks to the oceans that cover some 70 percent of its surface. Yet despite their dominance we really know very little about them. Our soft human bodies just aren’t designed to withstand the intense pressures of the deep oceans, let alone the lack of air for lungs to breathe. But there are some intrepid few who have descended into this vast and seemingly forbidden underworld and lived to tell of its marvels. Journalist Susan Casey is among them, and in her latest book, The Underworld: Journeys to the Depths of the Ocean, she illuminates the immense world miles beneath the surface and the people committed to exploring it, and she joins me now. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Susan!

CASEY: Thanks, Steve.

CURWOOD: So when you step into the formal text of your book, you start talking about the history of the ocean and how humans thought of it as filled with monsters hundreds of years ago, their drawings are some famous ones. There are myths that Atlantis is down there. This is supposed to be a fairly spooky place. Of course, nowadays, we know better. But I have to say some of the photos in your books of some of the deep-sea creatures, well, maybe they are kind of monstrous. How do you think about both how far we have come in understanding the ocean and the mysteries that remain?

The Limiting Factor landing on the seafloor of the Mariana Trench’s Challenger Deep, the ocean’s deepest spot (35,876 feet). (Photo: Courtesy of Susan Casey)

CASEY: Well, it's really exciting to me that basically, we're the first generations of people that will actually be able to know, what are these creatures, what is down there. Technology is helping us, but it wasn't all that long ago, only about 150 years, that nobody knew at all what the bottom of the ocean looked like, what it was made of, you know, what lived down there, did anything live down there? So there were, preceding that, a lot of superstitions and myths and lack of knowledge, which led to confusion, I think. And one of the things I say in the book is, imagine you're a medieval farmer, and you're walking along the shore in Scandinavia sometime during the 16th century. And you come across the stranded, beached body of a sperm whale, like what are you thinking that is? You don't really know. But it looks pretty monstrous. And we've been told, throughout sort of the deep history, that, you know, there were monsters in the Bible, there was Leviathan, there were monsters in Greek myths. They lived underwater in this hidden underworld that we weren't privy to. And the thing is, they really aren't monstrous, but they're very different from us. They have a very different set of evolutionary needs. They've adapted to incredible pressures. They've adapted to living full time in the darkness. And this is not something that we relate to, life that really doesn't look like us. It may not even obey the same basic laws of life that we do, that, you know, say we thrive on photosynthesis. There are creatures at the bottom of the ocean that will never see the sun. And so their lifeforce is basically coming from the internal heat and minerals and gases and microbes from the planet in a process known as chemosynthesis. We only discovered this in 1977. So life had this entirely different trick up its sleeve that we didn't even know about. And we're still finding out all sorts of things. But I do think it's the otherness, sometimes, that makes people think ‘monster.’ But a lot of the times when you see these creatures, I mean, I tend to think of them as just adorable. A lot of the times they're quite small, the fish with the really big teeth and the big eyes, that's what you get when you adapt to living in the darkness 100% of the time, and food doesn't come along very often, and when you catch it, you have to have jail bars on the front of your mouth to make sure it doesn't get away.

CURWOOD: Now, of course, you point out in your book that yeah, maybe they don't have the visual acuity all the way down, but they use sound in intricate and exquisite ways.

The elongated bristlemouth, a tiny, glittery predator that is likely the most abundant vertebrate on earth. Trillions of these fish live in the uppermost layer of the deep ocean, known as the twilight zone (from 200–1,000 meters). More creatures live in the twilight zone than in all the other regions of the ocean combined. (Photo: Paul Caiger, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

CASEY: Oh, absolutely. I mean, sound travels far and fast in the ocean, more so than it does in air. And when you think about it, you know, we're primarily visual creatures. But that's not the greatest sense on a planet that's 95% in darkness 100% of the time. So there are other means in the ocean of communicating, and sound is one of them. There's also bioluminescence, which is the ability to create light. Not very many creatures have this on land. But in the ocean, it's a major part of the arsenal of tools that they have to be able to hunt, to mate, to get away from danger, to do all sorts of things. So when you go down in a submersible, you see these bursts of light, like fireworks kind of all around you. Because 80% of the animals in the uppermost parts of the deep ocean can illuminate themselves.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about the layers of the deep ocean. I mean, I've gotten to go, I don't know, maybe 70 or 80 feet down. And you know, with a tank strapped to my back at one point, there's a lot more ocean there. And you in fact, were able to go on a few deep-sea dives. What was that like? And talk to me about the layers that you went through.

A Sloan’s viperfish, also found in the twilight zone. Eighty percent of the twilight zone’s creatures use bioluminescence for hunting, mating, hiding, and other purposes. Deep-sea fishes like this one look fearsome, but most are quite small. (Photo: Paul Caiger, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

CASEY: When people think of the ocean, they typically think of the very uppermost layer, which is the sunlight or photic zone, where there's light through the water. And even at the deepest you can scuba dive, you're still seeing sunlight, at least there is sunlight in the water. But below that is the uppermost layer of the deep ocean, and that's the twilight zone or the mesopelagic zone. And that goes from 200 meters, so about 600 feet, down to 1000 meters, so about 3300 feet. And then below that you have another vast midwater area called the midnight zone that goes from 1000 meters to 3000 meters. Below that you have the abyssal zone, or the abyss, which goes - it's the largest ecosystem on Earth, and it's 3000 meters to 6000 meters. And then below that, in certain parts of the ocean, there's the deepest part. It's where the tectonic plates collide and one plate is being subducted beneath another, and that's from 6000 meters almost down to 11,000 meters in the deepest spot in the ocean. That's called the hadal zone. And those deep areas are called hadal trenches, where these tectonic plates are colliding. The Mariana Trench is one that people tend to know. But there are dozens of others. So the deepest spot that we know of is called the Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench, and that's 35,867 feet by our latest calculations. It's actually very hard to get an exact depth calculation. And I went as far down as the abyssal zone. I went about 17,000 feet, about 5200 meters. I also went through the twilight zone, which is really amazing, because I call it the Manhattan of the deep, because there are more creatures living in the twilight zone than in all the other regions of the ocean combined. So it's a really active place and very scenic because all these creatures are illuminating themselves and flashing and blinking and wafting in front of you and sparkling.

A Triton three-person submersible with a transparent pressure sphere at 3,300 feet in the Bahamas. Transparent pressure spheres offer passengers a kaleidoscopic view of the deep, but they can’t be used below 6,000 feet. At greater depths, a titanium or steel pressure sphere is required because of the immense pressures. (Photo: Courtesy of Susan Casey)

The abyss is... it took us two and a half hours of free falling to get down into that realm and get the sense that the deeper you go, the more profound it feels. You're definitely aware of the weight, the pressure. I mean, that's 500 atmospheres on your head. There's a gravitas to it. But there's also a serenity, a real serenity, you realize that it is not space, because it's alive. I never forgot where I was. But I was in such awe of where I was that the time goes very elastic, like you could be down there for an hour and you would think you were down there for 15 minutes. There's no signposts. There's none of the things that we tend to look for above, you know, that give us a sense of our surroundings. It's all fluid. It's a spectacular experience that really changes your perspective of your place on Earth. This vast, vast, vast region that we never even think of - it is the vast majority of the Earth. So it's amazing to meet it.

CURWOOD: It's interesting the nomenclature, though, we use culturally. All the way at the bottom, the Hades zone. Hades, the god of the underworld. Your book, in fact, is called The Underworld. And in a colloquial way, we are thinking of, you know, crime, the wrong side of life when we talk about the underworld. Why did you pick this title? Why did you pick this name? And why do people who look at the oceans use such names to describe what's there?

Leptothecata jellyfish are one of the many creatures living in the twilight zone. (Photo: Paul Caiger, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

CASEY: Well, I think we have it baked into our language, you know, enlightenment, you're being raised up. And anything that takes us upward toward the light, like, up is good, down as bad. And we're kind of scared of bad, you know, it's dark, and we don't know what's there and we can't breathe. But to go into the underworld in Greek mythology is, it's the hero's journey. It's, you’re going down there, and it's not an easy journey. It takes humility, actually, it's the opposite of conquest. When we go into the deep ocean, we're using the best technology that we have, the best engineering that we, we have, and we know exactly what kind of forces we're going to be meeting. At the bottom of the Mariana Trench, for example, it's, you're gonna have 16,000 pounds of pressure per square inch. So there are rules that you have to adhere to, to be able to make this journey and come back home. And we're not necessarily the best at that. We're good at, you know, we love to the idea of blasting our rockets into space, and maybe we'll get a Mars colony, and maybe we'll expand our reach. But the inward journey, the journey into darkness, it's a different kind of journey. And the underworld in other cultures, it - that's where they kept the treasure. And I mean, I think that's one of my major theses in this book, is that this is a realm that is magical beyond measure, fascinating beyond measure. And we've neglected it, even though it really behooves us to understand more about it, because we're a little bit scared of it. And some people are a lot scared of it. But it is where the treasure is.

A species of cusk eels known as robust assfish, found in the waters as deep as 27,000 feet. These assfish live in the ocean’s deepest realm, known as the hadal zone (named after Hades, the underworld). (Photo: Alan Jamieson and Thomas Linley)

CURWOOD: So your book describes a series of some kind of amazing characters, people who, in fact, decide to go down there. Talk to me about some of those people and their love of this underworld.

CASEY: When I report my books, I try to embed myself with people that are sort of doing the most extreme things in the environment that I want to write about and doing them well, so that there's a sense of being on the cutting edge as I'm following them through, say, in this book, it was embedding with the Five Deeps Expedition, which took place in 2019, and it was sort of the debut of the first full ocean depth manned submersible, which was owned by an individual named Victor Vescovo, businessman from Texas, who's also a very committed adventurer. And by the time I met up with him, Victor had already been to the top of the tallest peaks on every continent and skied to the north and south poles, and had looked around and thought, "Okay, what else can I do?" and was kind of shocked to find out that we hadn't been to the bottom of the hadal trenches, for the most part. And only three people in history had been to the bottom of the Challenger Deep, which is the deepest spot in the Mariana Trench. And in the time that it had taken three of us to get down there, you know, like 200 people had been to the International Space Station and thousands of people had been to the top of Mount Everest. So he thought, "Well, wait a minute, let's do that." I tend to like very obsessive, very colorful characters, and he is certainly one. He commissioned, I think the best submersible company in the world, this company Triton Submarines based in Florida (I call them the Apple of submarine design) to create a two-person sub that could repeatedly go safely to the bottom of the deepest spots in the ocean every day of the week. And we had never had such a vehicle. It was not necessarily agreed upon that it was even possible because of the pressures to do this. And so Five Deeps was this sort of historical expedition that I was fortunate enough to be able to embed myself with. You know, in nonfiction, I make room for luck. And this was really a stroke of luck, timing wise, because I think in the history of deep-sea exploration in the future, will be divided before this submersible and after this submersible. It really opened up the hadal zone. And along with taking me down there, Victor also took a whole lot of hadal scientists who had been studying this realm, and it's not easy to study the deepest parts of the ocean, but they had never seen it. So he took them down in person. It just changed everything, this submersible, so I really wanted to share all kinds of details of that with readers.

These hadal snailfish, photographed in the Mariana Trench, are the world’s deepest fish. They’ve been found as deep as 29,300 feet and have adapted to the hadal zone’s crushing pressures. Hadal snailfish have no swim bladders or other air cavities in their bodies; their innards are encased in a buoyant, transparent gel. (Photo: Alan Jamieson)

CURWOOD: You have the curiosity for what's down there, then you get to go. What did you discover?

CASEY: I love the question because you discover things about yourself. You discover this perspective, our place on Earth, like I really am a fan of this humility in the face of nature that's bigger than we are, so much bigger than we are. And I think it's very hard for people to wrap their heads around how vast the deep ocean is. Everything we know, we see on land, is 2% of Earth's biosphere. The deep ocean is 95. So you get the sense of yourself as exquisite, but insignificant piece of the cosmos. You know, we're just here as part of it. And I love that. I love that feeling of humility, of being part of nature and being able to sort of revel in it. I think we lose sight of the fact that we are part of nature, and we think our job is to run it and own it, and, you know, use it. That's a delusion, and the ocean will set you very straight about this very fast.

CURWOOD: So, Susan, before you go, what do you hope for the future of underworld exploration?

Susan Casey, the author of The Underworld, entered the hatch of Victor Vescovo’s full ocean depth sub, the Limiting Factor. (Photo: Joe MacInnis, Courtesy of Susan Casey)

CASEY: You know, if you're not claustrophobic, I think going deep, like going below 600 feet if the possibility arises, and I think there will be more opportunities in the future to do this safely, it really is something that I think everybody would revel in, except for possibly claustrophobic people. But I just think that it is, the ocean is the greatest teacher, and the deep ocean in particular, for the sense of humility. I think it's a superpower. And I wish we could avail ourselves of it more above the surface, because I think that we would have a smoother ride. If we realize that this is all this massively interconnected, intricate system, and we're just beginning to understand that, and we should move with respect and caution. And at the same time, just delight in the beauty of it. Because everybody thinks they know that the deep ocean is spooky and scary, but I don't think people realize at all how beautiful it is.

CURWOOD: Susan Casey's book is called The Underworld: Journeys to the Depths of the Ocean. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

CASEY: It's my pleasure.

Related links:

- Explore more of Susan Casey’s work.

- Learn more about the Five Deeps Expedition

- Differentiate the ocean’s zones.

- Purchase The Underworld and support both local bookstores and Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Abel Korzeniowski, “Dance For Me Wallis” on W.E.-Music From The Motion Picture, Interscope Records]

There’s much more to discuss about the deep ocean, and we’re excited to let you know that we are planning to host a live event this May with Susan Casey at the New England Aquarium in Boston and online. We’ll dive into topics such as polymetallic nodules on the abyssal seafloor that some companies want to mine for their metals that can include manganese, iron, cobalt, copper, and niobium.

CASEY: How they form is that there's a nucleus, some hard scrap on the sea floor. And then over millions and millions and millions of years -- think of how pearls form -- metal precipitates or accrete from the seawater and builds in atomic layers around this nucleus. And eventually you get something that might be the size of a plum or an apple, and they're embedded in the sediments, but they're not just lumps of metal, they actually grow. So a better analogy would be trees or corals, because they have microbial life and other microorganisms and larger animals living on them, under them, inside them. 50% of the animals that are found around nodules are there only because of the nodules. They’re a hard substrate to cling on to, for animals like sponges, lots of different sessile animals, a really large part of a very stable ecosystem that we have not had our paws on up till now.

DOERING: We’ll talk with Susan Casey about that and much more this May. Stay tuned for the date and how you can attend. You can sign up for our newsletter at loe.org to make sure you don’t miss out.

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Quentin Bell, Paloma Beltran, Josh Croom, Karen Elterman, Swayam Gagneja, Sommer Heyman, Mattie Hibbs, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Sarah Mahaney, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments@loe.org. I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth