February 16, 2024

Air Date: February 16, 2024

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

$250 Billion Yearly Economic Costs from Plastics

View the page for this story

Hormone-disrupting chemicals in plastics take a yearly economic and health toll in the hundreds of billions of dollars in the U.S. alone, according to a recent study. Pediatrician Leonardo Trasande discusses the research with Host Steve Curwood and explains why PFAS, phthalates, BPA and flame retardants in plastics are so harmful to human health. (16:03)

Exxon Sues Climate Investors

View the page for this story

ExxonMobil recently sued activist investors in federal court in Texas for a repeated effort to bring a climate resolution to a vote at the company’s annual shareholder meeting. The giant oil company has persisted even though the activists have withdrawn the petition. Pat Parenteau of Vermont Law and Graduate School joins Host Paloma Beltran to explain the backstory and chilling effect Exxon’s actions could have on investor engagement. (11:17)

Mann Bites Lapdogs (Beyond The Headlines)

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Living on Earth Contributor Peter Dykstra and Host Steve Curwood catch up on climate scientist Michael Mann’s $1 million legal victory over bloggers who were found to have defamed him. Also, Puerto Rico is encouraging more solar development to help with grid reliability and reduce emissions, and in history they look back to when an ice jam left Niagara Falls high and dry. (05:21)

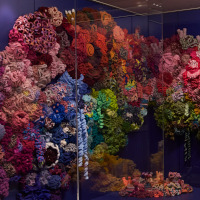

The Crochet Coral Reef

View the page for this story

To raise awareness about the threats facing coral reefs, crafters everywhere are picking up their crochet hooks and contributing to a worldwide “Crochet Coral Reef.” Host Paloma Beltran spoke with Alyssa Velazquez, the curator of the Pittsburgh Satellite Reef at the Carnegie Museum of Art about what it’s like to stand inside the exhibit and how it came together. (10:59)

Remembering Bob Edwards and Ross Gelbspan

View the page for this story

Host Steve Curwood shares some recordings and memories of the late Bob Edwards and Ross Gelbspan, two giants of journalism who helped support Living on Earth from its earliest days getting on the air. (03:10)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

240216 Transcript

HOSTS: Paloma Beltran, Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Pat Parenteau, Leonardo Trasande, Alyssa Velazquez

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

Toxins in plastic are costing our health and the economy hundreds of billions.

TRASANDE: There are downstream costs that are terribly important at a societal level, and we ultimately pay because the chemical industry contaminates us through the products we use in our daily lives and through the chemicals that are used in those products and in particular plastic.

CURWOOD: Also, an eco-illusion of a coral reef created with crochet.

VELAZQUEZ: A coral colony found its way out of the Gulf of Mexico, through the Mississippi, converged as a group along the Ohio, swam the Allegheny or the Monongahela River, depending on which one they wanted to swim, and they just started growing in our galleries for our visitors near and far.

CURWOOD: Those stories and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

$250 Billion Yearly Economic Costs from Plastics

Many chemicals used in plastics disrupt normal hormone function and can hurt human health, costing the US upwards of $250 billion a year in healthcare costs. (Photo: Laura James, Pexels)

BELTRAN: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Paloma Beltran.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

$250 billion. That’s the annual health and economic costs of toxins in plastics in the United States, from the plastics found everywhere, in food packaging, clothing, furniture, cookware, and even nail polish. They’ve come to permeate our environment so thoroughly that some have started calling our time the “Plasticene.” Plastic trash is ugly enough, but the invisible host of chemicals they contain wreak havoc on the hormone systems of the human body, leading to devastating and costly health outcomes. A recent study published in the Journal of the Endocrine Society found that in 2018 alone, disease and disability caused by chemicals in plastic cost the U.S. a whopping quarter of a trillion dollars in health and economic losses. Lead author Leonardo Trasande is a pediatrician who directs the NYU Center for the Investigation of Environmental Hazards and he joins me now. Dr. Trasande, welcome back to Living on Earth!

TRASANDE: Thanks for having me again, Steve.

CURWOOD: So your study focused on the costs of just a few of the thousands of chemicals that are used in plastics. What were the chemicals that you included in your study? And how do they threaten our health?

TRASANDE: So we started by focusing on brominated flame retardants. Brominated flame retardants are best known to hack thyroid hormone. The baby relies on thyroid hormone through the second trimester of pregnancy, such that even low levels of thyroid hormone can disrupt brain development in the young child and have consequences that are permanent and lifelong. Then we also focused on phthalates, chemicals used to soften plastics that not only have effects on metabolism in adults as well as kids, but disrupt sex hormone function and thereby can have effects on fertility. And these chemicals, particularly the phthalates, may have behavioral consequences not just for attention deficit, but for depression and other mental illnesses. We also looked at bisphenols used in polycarbonate plastic and aluminum can linings. Bisphenols are synthetic estrogens, they mess with fat distribution in the body by disrupting how cells in the body develop. Instead of bone or muscle, they become fat. And they disrupt the protective function of proteins that are important for heart function. And then finally, there are these forever chemicals as they're called, per and polyfluoroalkyl substances, nonstick chemicals that are used in oil- and water-resistant clothing, too. They do a host of things. They contribute to cancers, they disrupt metabolism, they can impair cognitive function. And the reason why these chemicals have such broad effects is they weren't designed with the human body in mind the way drugs are. And so you mess with hormones, you have reverberations that cut across all sorts of organ function in the body.

Plastics can be found in unexpected places like furniture, clothing, and even nail polish. (Photo: Maksim Goncherenok, Pexels)

CURWOOD: And we have an obesity epidemic in this society. How might exposure to these chemicals and plastics be related to that?

TRASANDE: So we used to think, simply calories in, calories out. And nothing I'm saying today mitigates the importance of diet and physical activity in the twin pandemics of obesity and diabetes in the U.S. and globally. But we know that chemicals can scramble our body's response to normal dietary cues. Take for example a study that followed a population of adults who had lost weight through healthy diet and physical activity. They drew a blood sample, they measured PFAS in that blood sample, and then they saw who gained weight back the fastest. The ones who gained the most weight back were the ones with the highest levels of PFAS. And then they dug in deeper. And they found that the resting metabolic rate of those adults had actually slowed down in relationship to the chemicals. So talk about the body's thermostat being turned the wrong way.

CURWOOD: Now your study found that using these chemicals in plastics costs us some $250 billion in U.S. health costs a year, I guess you said maybe between 225 and 275. But it's still a huge number. So what kind of costs did you include in those calculations?

TRASANDE: Well, to just start at the basic level, we looked at direct medical care costs, doctor's visits, prescriptions, emergency room visits, hospitalizations. But you have to dig deeper, because there are downstream costs that are terribly important at a societal level. And we ultimately pay, because the chemical industry contaminates us through the products we use in our daily lives and through the chemicals that are used in those products and in particular plastic. So just take lost economic productivity. A big driver of our costs was early death from phthalate-induced cardiovascular mortality. That's mortality during people's peak productive years. And so those are big dollar drivers, often over and above the cost of the medical care that you can count. Another example is when a child doesn't perform well in school, I might not notice as a pediatrician, the mother might not notice, the teacher might not notice. But if 100,000 kids lose an IQ point, the entire economy notices, because each IQ point is worth a 2% decrease in that child's ability to perform in the economy. And if somebody makes on average a million dollars over his or her lifetime, 2% of a million dollars is a big number, particularly when you multiply that by 4 million births in the U.S. each year.

Chemicals used in plastics like PFAS have been linked to obesity. (Photo: Andres Ayrton, Pexels)

CURWOOD: So give me some context for this enormous number. I mean $250 billion. How big a deal is that?

TRASANDE: It's 1.2% of the gross domestic product of the United States. The chemical industry profits to the tune of $750 billion a year. So that's not even a great return on investment. That's a loss of 1/3 of that economic output as a result of disease and disability. When you put that side by side with U.S. healthcare costs, it's a bit of apples and orange comparison, I'm just going to be honest intellectually, but it's about 5%. In the big picture here, we looked at only maybe 10 or so chemicals used in plastic. There are thousands. And then we only looked at a subset of diseases due to the few chemicals we studied. And a subset of costs due to the few diseases due to the few chemicals we studied, so I'm afraid to say that the costs that we identify here, may actually be much, much bigger.

CURWOOD: This number, though, is one of those classic problems of externalities for pollution. Somebody makes products, spews it in the air or distributes it, but somebody else pays for the impact of that. And the plastic-making companies, they are profiting, well, let's face it, they make a lot of money from our addiction to plastics. So if we can't get the companies to pay for these costs, who will? And actually a sub-question of that is, what's the point of your research, pointing out this huge burden if no one's going to pick up the tab?

The stated figure of $250 billion in healthcare costs from toxic plastics is comprised of both direct medical costs and indirect economic costs, such as lost economic productivity due to early mortality. (Photo: Pixabay, Pexels, CC BY 2.0)

TRASANDE: Well, the point of the research is that we all pay the cost of the profit of the chemical industry in this case. And right now, countries across the globe are negotiating a Global Plastics Treaty. It's a landmark watershed moment in history where we can take on the challenge of the plastic threat to our planet. Now, there are some people out there, particularly from the chemical industry, that are pushing very hard to make the plastic pollution threat just a waste threat. They want you to focus on the Pacific Garbage Patch, for example. But we all have a little bit of that Pacific Garbage Patch in our bodies, and it's harming us, it's hacking our hormones and contributing to disease and disability. So we not only need to get rid of waste from plastic, we need to reduce our use and production of plastics, period. That's going to face a lot of resistance from within the U.S. delegation because we produce, as an economy, a substantial amount of plastic, not just for the United States but for the planet. And we're only recycling 9%—lifetime—of plastics on our planet. The best rates of plastic recycling are 30%. And so if we don't turn off the tap, what will happen is this plastic will accumulate even more in our bodies, and the disease burden that we're talking about will escalate even further.

CURWOOD: But be clear with me for a moment. If we were to recycle all of the plastic that's out there, to what extent will we still be at risk from disease?

TRASANDE: Even more, in an indirect way, because when you recycle plastic, you don't simply do a basic burn and reuse kind of operation, you add chemicals to it to make the plastic reusable. And the few studies that are out there have documented that chemical contamination in recycled plastic, including heavy metals, by the way, is higher than the virgin plastic. And so we need to use the Global Plastics Treaty as a chemicals treaty. A lot of people want to just sweep the chemicals under the carpet. But there are tens of thousands of chemicals used in plastic materials to this day, of whom 12 or so have been regulated by existing environmental conventions globally.

Attendees of the 2022 United Nations Environment Assembly celebrate the passing of a plastics resolution, which called for the UN to recognize and address concerns related to plastic pollution. A Global Plastics Treaty is now being negotiated. (Photo: UNEP/ Cyril Villemain, Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: So if I'm hearing you correctly, if you were in charge of everything, you would simply get rid of plastics from our society, at least the way that they're made right now.

An art installation showing plastic waste flowing from a “tap” at the 2022 United Nations Environment Assembly. (Photo: UNEP/Ahmed Nayim Yussuf, Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

TRASANDE: Well, I wouldn't get rid of essential plastic. There is a distinction here. I use the analogy of the cucumber wrapped in the proverbial plastic tight wrap. That cling wrap has no use. No logical use. During the pandemic, when I started flying again, I would see these tray tables be delivered to me with an extra two layers of plastic wrapped under the guise of well, I'm trying to prevent COVID by doing this. COVID is transmitted by air particles, not by droplets. So it was the biggest plastic theater episode that I have ever witnessed. We seem to have gotten into the mindset that plastics is the future. Plastics have definitely provided crucial innovations to our life as a society. But the pendulum has swung way too far. We are excessively focused on profiting from finding any potential use of plastic in our life.

[MUSIC: Biff Smith, “Five of a Kind” on Biff Smith Solo Piano, by Biff Smith, self-published]

CURWOOD: We’ll be back after the break with more from our conversation with Leo Trasande about chemicals in plastics, including solutions. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

Although the FDA banned Bisphenol A (BPA) in baby bottles and sippy cups in 2012, it did not prohibit the use of the chemical in water bottles and other plastic containers. (Photo: Andrew Seaman, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

[MUSIC: Biff Smith, “Five of a Kind” on Biff Smith Solo Piano, by Biff Smith, self-published]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Jimmy Smith/Thornel Schwartz/Donald Bailey, “Willow Weep for Me” on At the Organ, Volume 3, by Ann Ronell, Blue Note Records]

BELTRAN: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Paloma Beltran.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

We’re back now with pediatrician Leonardo Trasande with more about the enormous costs of toxic substances used in plastics. These chemicals are powerful endocrine or hormone disruptors linked to health problems as varied as fertility issues, developmental delays and obesity, just to name a few. Even so-called bioplastics made from vegetable oils, food waste and cornstarch instead of petroleum are often laced with them. But there’s little regulation of the consumer products and even food packaging that chemicals like PFAS, phthalates, and Bisphenol A or BPA wind up in.

TRASANDE: Well, we've generally failed, particularly when it comes to the Food and Drug Administration. Take BPA or Bisphenol A, for example. We knew that it was a problem back in 2008. So the FDA banned it in baby bottles and sippy cups but didn't ban it in any other plastic materials. Let's go to phthalates now. The Consumer Product Safety Commission banned eight phthalates in toys, or restricted them to a very low level. The Food and Drug Administration has only limited two of those eight. So talk about a logical inconsistency. It's not as though kids don't eat food from packaging the same way they play with toys.

Bioplastic packing peanuts. Bioplastics come from biological sources such as starches or vegetable oils. Although they are sometimes advertised as safer than petroleum-derived plastic, they can also contain endocrine disrupting chemicals. (Photo: Christian Gahle, nova-Institut GmbH, CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: To what extent is dealing with this problem a bit of "whack-a-mole"? Because when one type of chemical is taken off the market, let's say Bisphenol A, industry comes up with Bisphenol S. How safe are the alternatives that industry has been putting forth when certain chemicals are identified as problematic?

TRASANDE: Unfortunately, the little we see is that these are not safer. Bisphenol S is a prototype example. It's as estrogenic, as toxic to embryos and as persistent to the environment. Bioplastics are often proposed as a whole other alternative. But what little we know about bioplastics, which you would assume are naturally derived and safe, right? Nope. They are as endocrine active and endocrine disrupting as the chemically based plastic. There are safe materials. It's just that we have become aware of the many different ways in which things that we thought were safe are actually not.

CURWOOD: So for someone who's listening to us right now and concerned about this, what steps can they take to protect themselves and our society as we wait for some sort of response from the politicians that govern our regulations?

TRASANDE: So there are safe and simple steps we can take in our lives to reduce our plastic footprint and protect ourselves. If you need to use plastic, particularly don't machine wash or microwave plastic. The chemicals in some cases we're talking about are not covalently bound to plastic and the harsh ingredients and high temperatures can lead to degradation and eventually absorption of those chemicals into food more readily. Also, avoiding certain recycling number plastics is important because three is for polyvinyl chloride, which typically adds phthalates. Six is polystyrene, which breaks down into styrene, a known carcinogen. And seven is typically for polycarbonate plastics, which include bisphenols. But more generally, we can reduce our use of plastic. People use plastics in our daily lives when they actually could save money and save grief by using glass or stainless steel.

Dr. Leonardo Trasande is a pediatrician who directs the NYU Center for the Investigation of Environmental Hazards. (Photo: Cheryl Stockton)

CURWOOD: This is so overwhelming that a quarter of a trillion dollars every year, it's costing people in this country, in other words, every four years that's a trillion dollars, because of the health effects from plastics. It's a huge number, it's overwhelming. What gives you hope?

TRASANDE: What gives me hope is we've seen decreases in levels of these chemicals of concern over the past two decades. BPA levels, for example, have declined as attention to BPA-free materials has come into vogue. Now that's come with some unfortunate consequences, there are some replacements of BPA that are starting to come on the scene and detectable in people. But again, the awareness has fundamentally changed. And the more we keep growing awareness of this issue, people will use the power of the pocketbook or wallet to drive the change they seek. Ultimately, these companies are accountable to the consumer. So it's the consumer that gives me hope, not to mention the fact that with the attention to climate change, particularly among Generation Z, you have a spirit of awareness that is there that hasn't been there before.

CURWOOD: Dr. Leo Trasande is a pediatrician who directs the NYU Center for the Investigation of Environmental Hazards. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

TRASANDE: Always a joy to be with you Steve. Thanks again.

Related links:

- Journal of the Endocrine Society | “Chemicals Used in Plastic Materials: An Estimate of the Attributable Disease Burden and Costs in the United States”

- Environmental Health News | “Chemicals in Plastic Responsible for Nearly $250 Billion Worth of US Health Costs in a Single Year”

- New York University | “Center for Investigations of Environmental Hazards”

[MUSIC: Open Road Folk Music “Light On The Mountain - Instrumental” on Instrumental Indie-Folk, Vol.2, alexrainbirdRecords]

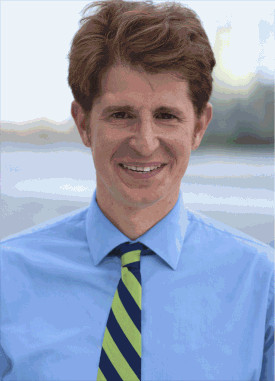

Exxon Sues Climate Investors

The activist shareholders’ resolution called on Exxon to set targets limiting Scope 3 emissions, which include emissions from customers burning gasoline in their cars. (Photo: Mr. Satterly, Wikimedia, Public Domain)

BELTRAN: Much of the world aims to slash greenhouse gas emissions in the coming decades, and even some fossil fuel companies are adding clean energy to their portfolios. But others are digging in and fighting back. ExxonMobil recently sued activist investors in federal court in Texas for a repeated effort to bring a climate resolution to a vote at the company's annual shareholder meeting in May. The investment firm Arjuna Capital and shareholder activist group Follow This had filed a resolution last year asking Exxon to adopt tighter emission targets on what are known as “Scope 3” emissions. Those are the greenhouse gas emissions that happen when we fill up at an ExxonMobil pump and then burn that gasoline in our cars. The Securities and Exchange Commission is in the process of drafting rules that would require companies to disclose Scope 3 emissions so that shareholders are aware of climate-related financial risks. But Exxon claims that since a similar resolution was already defeated, the activists are out of line, and the company is using its huge economic muscle to push back against them. Critics say it sends an intimidating message to any activists who try to challenge the oil giant, despite the responsibility of shareholders of public companies to see that they are well run and well managed. Even though Arjuna Capital and Follow This have withdrawn their proposed shareholder resolution, Exxon hasn’t dropped its lawsuit. In a statement on the Living on Earth website, loe.org, Exxon said in part, “the intent of our lawsuit is simple – we want clarity on a process that has become ripe for abuse.” Here to discuss is Pat Parenteau, an Emeritus professor at Vermont Law and Graduate School. Pat, welcome back to Living on Earth!

PARENTEAU: Thanks, Paloma, good to be with you.

BELTRAN: So what was the resolution brought forward by these shareholder groups? And what are these shareholders asking Exxon to do?

PARENTEAU: So the resolution is fairly short. And it's asking Exxon to set targets and timetables to reduce what are called Scope 3 greenhouse gas emissions. And what that means is, it's all of the emissions connected with the supply chain that delivers Exxon's products, of course, gasoline, to consumers. So the Scope 3 emissions are the largest segment of emissions that Exxon is responsible for, it's the biggest chunk of their emissions, it's about 70-plus percent of the total emissions that Exxon is putting into the atmosphere every year. So that's what the shareholders were trying to put on the ballot for the meeting, which is in May, for Exxon shareholders, the annual meeting.

BELTRAN: And from what I understand, after this resolution, Exxon pushed back and actually sued the shareholders. What is Exxon's strategy here? Why would a company sue its shareholders? And why would they continue to do so after the resolution was dropped?

An Exxon Mobil building in Houston, Texas, where the company is headquartered. The company filed its lawsuit against the activist investors in the in the Northern District of Texas federal court. (Photo: WhisperToMe, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

PARENTEAU: Well, part of this, frankly, relates back to when a group of shareholders were able to put members on the board of directors for Exxon. And this was obviously over Exxon management's objections. And the management of Exxon has been smarting from this move to put shareholders on their board, which, frankly, want them not only to reduce their emissions, but ultimately, to change their whole business plan. So in context, you know, this is part of all the pressure that's being put on Exxon, and Exxon is now pushing back. Normally, what happens when shareholders seek to put a resolution on the agenda, Exxon has to go to the Securities and Exchange Commission and request permission to block the resolution from being placed on the ballot for the annual meeting. Exxon did not do that in this case. This is the first time that Exxon has ever bypassed going through the Securities and Exchange Commission and gone directly to court to stop the resolution from being placed on the ballot. So, first time.

BELTRAN: And, you know, Pat, you mentioned Exxon bypassed the regular SEC legal process. How might this affect investor engagement?

PARENTEAU: Well, it certainly is a chilling effect, isn't it? I mean, if the price for you putting a resolution on the agenda is you get sued, that's going to discourage a lot of shareholders, and certainly the smaller shareholders. And I think that's a legitimate concern, that Exxon is bullying these small investors, because they know they don't have the resources, basically, to fight legally in court with Exxon. And so Exxon is, you know, they're using a hammer, frankly, approach to this situation. Exxon may have a legitimate point that you can't just keep repeating over and over the same resolution. That's legitimate. But there is a process for determining that through the SEC. And that's obviously why that process is there. And of course, Exxon went to Texas to file this case, no surprise there. That's a home-court advantage for them. And they directed this case to a Trump appointee, who has ruled in favor of oil companies before. So this is a staged attempt, you know, to not just knock out this resolution, but discourage anybody else from thinking about doing the same thing.

An Exxon oil refinery in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, in 2017. Exxon has faced pressures from governments, shareholders, and international markets regarding the company’s disinformation about the climate and contributions to climate change. (Photo: Wclarke, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

BELTRAN: How does Exxon's behavior when it comes to emissions resolutions like the ones brought forward by these shareholders compare to other fossil fuel companies?

PARENTEAU: Well, Exxon is the outlier in this regard. The other major Western, as we call them, oil companies like BP, Shell, Conoco, they have all adopted resolutions that were very, very similar to the resolution that these two groups are trying to get Exxon to adopt. In other words, these other resolutions do deal with Scope 3 emissions, which are admittedly the most difficult ones to deal with. But the point is, Exxon is digging in its heels. It's part of a pattern that we've seen with Exxon in responding, for example, to cases we've talked about before, where states and cities are suing them for the damage from climate change, and they are countersuing these governmental entities, they are pillorying them in the media, insulting the individual mayors and governors that are bringing these cases and so forth. So this is the playbook for Exxon, they play rough. You know, this is a no-holds-barred kind of defense of what Exxon is doing.

BELTRAN: And in this case, the Norwegian sovereign wealth fund, which owns a sizable chunk of Exxon stock, issued a response to Exxon's lawsuit. What does this mean, Pat?

Pat Parenteau is emeritus professor of law at Vermont Law School and formerly served as EPA Regional Counsel. (Photo: Courtesy of Vermont Law and Graduate School)

PARENTEAU: Yeah, so that's a major shareholder, I mean, percentage-wise, it may only be 1%. But you're talking about a company that's valued in the hundreds of billions, right. So that's the kind of shareholder that has the muscle, I think, to push one of these resolutions. The Norwegian sovereign wealth management fund did not file its own resolution, it supported these other groups' resolution. But it'll be interesting to see if one of the major institutional investors decides to take up the cause and come back at Exxon, maybe with a more refined resolution, one that is different enough from the ones that were previously tried that you could legitimately say it's a new resolution, and you don't run into this repeated resolution problem. But there are plenty of ways to frame a resolution. The best benchmark for these resolutions is to refer to the commitments made in the Paris Agreement. And there's a term of art that we could use called Paris-compliant corporate policies. And many corporations—Google, Microsoft, others—have signed up for these Paris-compliant protocols, if you will. So it may be that one of these major investor groups can frame a resolution that's different enough from the ones that were voted down before that they can get it back on the ballot in a future annual meeting, and then see what happens.

BELTRAN: So what power do shareholders have in continuing to raise their voice on climate and transparency issues like the ones brought forward by Arjuna and Follow This?

PARENTEAU: Shareholders have a tremendous amount of power. I mean, you know, the divestment movement that was launched by Bill McKibben and 350.org over 10 years ago, has, frankly, had a major impact on the fossil fuel industry. I mean, trillions of dollars have been divested. So you know, there's that aspect of institutional investors simply disinvesting and reinvesting in other cleaner sources of energy, that's part of it. The other thing that's going on that should be mentioned is that the SEC is still working on finalizing a rule requiring more robust disclosure of emissions from companies like Exxon, and also identifying that there is a material risk to shareholders from companies that are not transitioning away from fossil fuels. So what I'm suggesting is there are different avenues to put pressure on the companies, there's going to be pressure coming from the government, pressure coming, frankly, from the international markets in the European Union, and pressure coming from shareholders, as well as pressure coming from these lawsuits against the company seeking damages. So all of these different vectors. I think, ultimately, the goal would be to move these companies much more quickly into the transition that is inevitable if the question is how soon can we get there?

BELTRAN: Pat Parenteau is an emeritus professor at Vermont Law and Graduate School. Thank you for joining us.

PARENTEAU: Hey, Paloma, it's always a pleasure.

Response from ExxonMobil:

The intent of our lawsuit is simple – we want clarity on a process that has become ripe for abuse. We hope our suit motivates the SEC to go back to applying the proxy rules as they were written, not as they’ve been interpreting them over the last few years. The current process to get proxy proposals excluded is flawed and permits activists with minimal shares to bring an increasing number of repeat proposals that do nothing to grow long-term shareholder value.

Related links:

- Financial Times | “Norway Oil Fund Boss Criticises ExxonMobil’s ‘Aggressive’ Climate Lawsuit”

- Financial Times | “Investors Pull ExxonMobil Climate Motion After Oil Supermajor Sues”

- Reuters | “Exxon Files Lawsuit Against Investors’ Climate Proposal”

- Bloomberg “Investors Ask Court to Throw Out Exxon Suit Over Climate Bid”

[MUSIC: Joe Hicks, “Pieces – Instrumental” on Instrumental Indie-Folk, Vol.2, alexrainbirdRecords]

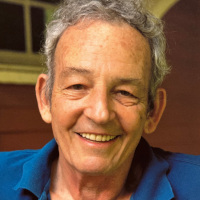

Mann Bites Lapdogs (Beyond The Headlines)

Michael Mann is a world-renowned climate scientist and a Presidential Distinguished Professor at the University of Pennsylvania. (Photo: Eric Sucar, Courtesy of Michael Mann)

CURWOOD: And now it's the time in the broadcast when we turn to Peter Dykstra. Peter is a contributor to Living on Earth and typically looks beyond the headlines for us, although he does offer other observations from time to time. He's on the line now from Atlanta, Georgia. Hi there, Peter. How you doing?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve. I'm doing well. And I hope you are too. We're gonna start with a landmark case, a big victory for climate science. Michael Mann, one of the best-known climate scientists, and that also makes him one of the biggest targets among climate scientists on a political and climate denial level. He just won a judgment for more than a million dollars. He was judged to have been defamed by bloggers who accused him of data manipulation and somehow drew an analogy to a child molester who had a famous case on the Penn State campus years ago. Mike Mann, in defense of his own work and that of other scientists, dove right into the political and the legal end of it, and took on the people who were found to have defamed him. It was a big victory for climate science, and a huge and costly loss for one of the sources of climate denial.

CURWOOD: That's right. I mean, Michael Mann, who has been on this broadcast a number of times because he does a great job of explaining climate science, had his emails hacked back in 2009, in the run-up to the Copenhagen UN Climate Summit. And these emails had some casual conversation among scientists that folks in industry tried to twist into, oh, this isn't really happening. That is, climate change isn't really happening, or the scientists are skeptical about it. And from then on, things were very difficult. And now he has this amazing victory against those people online who would defame him unfairly and frankly, maliciously.

DYKSTRA: Now there's a consequence for some of the worst of the climate deniers, and Mann is richer for it, although I don't think he ever got into this for the money. And now he's going to be much, much harder to attack irresponsibly, as are other scientists who deal not only with climate, but also things like vaccines.

CURWOOD: Hey, what else do you have for us today?

Puerto Rico is planning to convert massive amounts of their electrical grid over to solar power in hopes of creating a more reliable, sustainable system. (Photo: Chris Bentley, WBUR, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DYKSTRA: A story from Puerto Rico. And of course, Puerto Rico's electric grid was almost entirely taken down by Hurricane Maria back in 2017. The island went without power for a long time. Some of the more remote places in Puerto Rico went without power for months on end. A lot of corruption was found in the Power Authority there. That's been addressed, in addition to the fact that Puerto Rico has affirmed its commitment to turn more and more to solar energy.

CURWOOD: Right, I've seen the plans are to use solar to set up microgrids in various parts of the island so that when the storms come—and the storms come fairly often to Puerto Rico, given where it is in the Caribbean—that all the lights won't go out. Plus, when you use solar, you don't have to pay the oil bill, because central power in Puerto Rico was done by bunker fuel, expensive oil that had to be shipped over to the island, whereas Puerto Rico itself has plenty of local sunshine. And Peter, I believe, as we were getting ready for the broadcast, you told me they had put this in the law, actually, to go solar.

DYKSTRA: Right, and they specifically addressed climate change as a reason for going solar. Puerto Rico has arguably more to lose from climate change than many places in the world.

CURWOOD: Indeed. Time now to take a look back in history, Peter, what do you see?

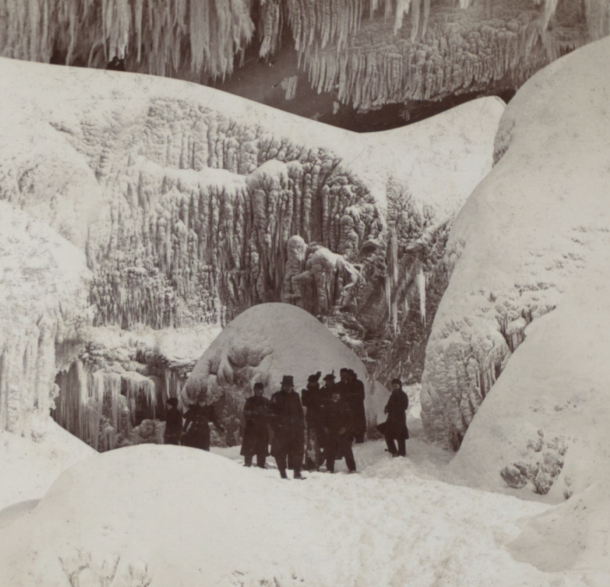

Niagara’s Cave of the Winds, photographed in the 19th century. (Photo: The Robert N. Dennis collection of stereoscopic views, New York Public Library, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

DYKSTRA: We can go back to February 18, 1896. An ice jam in the Niagara River above Niagara Falls reduced that landmark to a trickle of water, it blocked the flow over those 150-plus-foot twin falls. The Cave of the Winds, a famous part of the landmark, went virtually dry for the first time in 50 years. The falls going dry is a periodic thing, sometimes due to ice jams or droughts. Sometimes due to human intervention. In 1969, engineers blocked the American Falls, diverting water to the Horseshoe Falls on the Canadian side so that geologists could study the cliff on the American side. And again just a couple of years ago in 2022, the American Falls was briefly shut down to allow for repairs to century-old trails and bridges.

CURWOOD: Well thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is a contributor to Living on Earth, and we'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Okay, Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth webpage. That's loe.org.

Related links:

- The Washington Post | “Famed Climate Scientist Wins Million Dollar Verdict Against Right-Wing Bloggers”

- Grist | “As States Slash Rooftop Solar Incentives, Puerto Rico Extends Them”

- Learn more about Niagara Falls’ Cave of the Winds going dry in 1896

[MUSIC: Joe Hicks, “Pieces – Instrumental” on Instrumental Indie-Folk, Vol.2, alexrainbirdRecords]

BELTRAN: Coming up, we’ll visit a vibrant coral reef in landlocked Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Joe Hicks, “Pieces – Instrumental” on Instrumental Indie-Folk, Vol.2, alexrainbirdRecords]

The Crochet Coral Reef

Alyssa Velazquez, the curator at the Carnegie Museum of Art, organized the Pittsburgh Satellite Reef by color to mimic the way water filters visible light. (Photo: Sean Eaton, Courtesy of Carnegie Museum of Art)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

Coral reefs are in trouble. The upper layers of the oceans absorb most of the warming and around a third of the carbon dioxide emissions from the climate crisis, making the water hotter and more acidic. These conditions are leading to coral bleaching and making it harder for corals to grow. Back in 2005, sisters Christine and Margaret Wertheim, founders of the Institute for Figuring, learned about the threats facing coral reefs. And they felt inspired to pick up their crochet hooks. They got to work making corals of all different shapes and colors, and with the help of many other crafters and museums their project has grown into a worldwide Crochet Coral Reef with around 50 “satellite reefs.” One of those is on display until 2025 at The Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The project brought crochet workshops to diverse communities around Pittsburgh and collected contributions from nearly 300 crafters. Here to talk to us about the project is Alyssa Velazquez, who led the Pittsburgh Satellite Reef as a curator at the Carnegie Museum of Art. Hi Alyssa, and welcome to the show!

VELAZQUEZ: Thank you. I'm so excited to be here.

The Pittsburgh Satellite Reef combines layered “frilly cabbage leaves” with cylindrical structures to mimic actual coral reefs. (Photo: Sean Eaton, Courtesy of Carnegie Museum of Art)

BELTRAN: We're really happy to have you. So if someone was walking through the Pittsburgh Satellite Reef exhibit, what would they see?

VELAZQUEZ: The Pittsburgh Satellite Reef is on the second floor of our hall of sculpture along the balcony with this decorative iron railing that visitors can walk around to view the marble sculptures. There's this little U-shaped gallery. If you enter the gallery, you travel along a curved and glassed-in display case. If you ever been to an aquarium, you might recall a similar space with low lighting and almost floor-to-ceiling glass panels in front of you. And so behind that glass is a large-scale wooly archipelago, chromatically organized to represent how colors filter through water. In other words, as light passes through a great distance of water, color is selectively absorbed by the water. So for the installation, all the hot or warm colors, those pinks, those reds, those yellows are at the top. And as your eye moves down the 2D wall pieces and rests on the floor of the case to roam over the 3D coral sculptures, you're left with blues, and purples, and greens. So they're all growing out of the space that's painted a rich plum, purple color to better offset the multicolored yarn. And to create the illusion that a coral colony found its way out of the Gulf of Mexico through the Mississippi, converged as a group along the Ohio, swam the Allegheny or the Monongahela River, depending on which one they wanted to swim, and they just started growing in our galleries for our visitors near and far. Which was one of the reasons why we felt the Carnegie Museum of Art was a great fit for this project in a city known for those three rivers, Ohio, Allegheny, Monongahela, and those waterways have a trickle effect, literally and pardon the pun, but on the ocean acidification and coral health.

The Carnegie Museum of Art brought together 281 artists to make the Pittsburgh Satellite Reef. (Photo: Sean Eaton, Courtesy of Carnegie Museum of Art)

BELTRAN: Sounds absolutely beautiful. You know, coral reefs are often referred to as the rainforest of the sea. They can be huge, and they support approximately 25% of all marine species. As a curator, how did you try and convey the grandiosity of this diverse ecosystem?

VELAZQUEZ: As a curator, I knew that for the piece itself to really shine, we needed to get inventive with our display strategies. And one of the things that was working in our favor was the space itself, the fact that it was a boxed-in aquarium just waiting to be filled with specimen-like objects. I started looking at lots of pictures of home aquariums, as well as public aquariums. And they all have somewhat of a purple, blue, green tinge to them, which is where we came up with the background color. And then within the coral pieces that we started receiving from community members, wanting them to dictate a lot of the design. And so when thinking of 2D elements that we would mount on the wall, that was because a lot of the corals that were being generated in these workshops were flat, or what I would lovingly term frilly cabbage leaves. Then so those have more presence when you're able to lay them down and build on top of each other, and how much more presence would they have, if you lay them down, build them on top of each other, and then turn them upright and mount them on a wall. And so then you create a 3D effect that's coming directly at you from the back of the case, reaching out to the glass and in some cases, to give greater that effect of rogue corals growing in the space, some of the corals touch the glass. And that was really important for us to create it. And then in addition to those 2D elements, having 3D sculptures on the ground, so that you have a diversity of visitors that can come in from various ages, and that there is something on everyone's eye level to really catch their intrigue, and make them look in amazement at where they are, both like literally and physically within the space.

BELTRAN: So also the little people could see the exhibit and live it.

VELAZQUEZ: Yes.

Coral reefs around the world are threatened by the climate crisis and plastic pollution. (Photo: bryceguy72, DeviantArt, CC BY-NC-ND 3.0)

BELTRAN: It sounds like there's such a variety of different forms in this exhibit. Like layered cabbage leaves.

VELAZQUEZ: Right, so for the cabbage-leaf-shaped, what they call hyperbolic planes or the hyperbolic corals that are flat, we layered them on top of each other, or in some cases, to create dimensionality, especially on the 2D wall sculptures, I would condense them, you could say almost in a tulip-like shape, and then would stuff them into various crevices to create a sense of growing out of and blooming. So there were some more three-dimensional shapes. If you think of tubers that are very iconic of coral formations on ocean floors, those sometimes were given additional rigidity with cardboard, or we did fill them with the stuffing that are in teddy bears.

BELTRAN: What types of materials did people use to make these corals?

VELAZQUEZ: The material used to make the corals are varied. They are from simple weighted thread, to cassette tapes, to VHS's, to water bottles, to wire. It all depended on the crocheter's comfortability with a hook. And so if you look at the coral reef, you'll see some shiny bits, and that might be a little bit of a reflective cassette tape. Or you'll see some sparkly bits, and that might be a unique type of yarn that's very delicate and thin and has some metallic elements. Or you might see some really warm, earthy greens and reds, and that's coming from some basic medium-weighted yarns for beginners.

BELTRAN: So I have yet to live the exhibit, but I've been told that it includes acrylic nails, what is the significance of that?

The Pittsburgh Satellite Reef brought together people from across the generations to work on a unique crochet project. (Photo: Sean Eaton, Courtesy of Carnegie Museum of Art)

VELAZQUEZ: Yes, so as the exhibition space, I described that U-shaped gallery, that's the primary space that we display the coral reef, but we also within that hall of sculpture off of the balcony, one of the ways of accessing that gallery space is by a staircase. And when you're going up the staircase, on that second floor, there's a little niche with glass covering over it. And for that niche, we wanted to put some corals in. And I saw that we were developing an exhibition design that was very bombastic in the main exhibition space. And for this small case, I really wanted to explore some of the stereotypes from contemporary art museums, one of them being the white cube. So rather than painting it purple, like the main exhibition space, we left it white. And rather than filling it with as many corals as possible, I selected two corals. And so I created a space in which you could have a small coral and a large branch coral within a white box. And on the floor of this white box, where these corals seem to be growing out of, is a bed of white acrylic nails. As a material, they're plastic. A lot of the acidification in the oceans is due to our single-use and non-degradable plastic waste, but also this discussion about primarily the makers of the Pittsburgh Satellite Reef, but also most of the satellite reefs, part of the Worldwide Crochet Project.

BELTRAN: Why is having art that relates to the environment so important?

Velazquez created the feeling that the corals are alive and spreading by having them push up against the glass. (Photo: Sean Eaton, Courtesy of Carnegie Museum of Art)

VELAZQUEZ: I think you need exhibitions about the environment, about your local both land and water health, to inspire a pride of place, which Pittsburgh definitely has. We have a lot of Pittsburgh pride, and with good reason, but pride of place of how that fits in within the international discourse. How what we do here does matter. And that's both the metaphorical statement and the literal physical statement that what we do to these three rivers, they do have a cause and effect on the larger world. And that can be both negative and it can now be positive with this exhibition. We hope that individuals who participated in the project, they'll bring their family and loved ones from far and wide, to not just showcase themselves as being an artist, but to showcase what one person can do to inspire really positive change. I think that's what's so beautiful about having this exhibition.

BELTRAN: Alyssa Velazquez is a curator at the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh and was in charge of developing the Pittsburgh Satellite Reef. Thank you so much for joining us.

VELAZQUEZ: Thank you for having me. It's been a pleasure.

Related links:

- Read more about the Pittsburgh Satellite Reef.

- Understand the Institute of Figuring’s mission.

- Learn about coral bleaching.

- Watch Margert Wertheim talk about the coral reef project.

- Learn more about UpstreamPgh a nonprofit that works to secure equitable, just access to clean, natural water for all and collaborated on the "Crochet Coral Reef".

- Learn more "Crochet Coral Reef"collaborator Kid Ewe Knot

[MUSIC: We are the Fossils. “None the Wiser – Instrumental” on Instrumental Indie-Folk, Vol.2, alexrainbirdRecords]

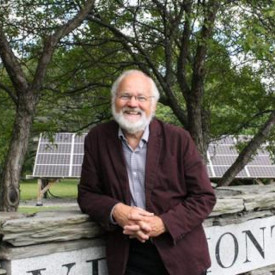

Remembering Bob Edwards and Ross Gelbspan

Ross Gelbspan was a journalist for several decades at a number of establishments, including The Boston Globe. (Photo: Courtesy of Thea Gelbspan)

CURWOOD: I’ve been saddened by the recent deaths of two giants of journalism, Bob Edwards and Ross Gelbspan, who were also good friends of mine. If you have long listened to public radio, you likely heard Bob during the nearly a quarter of a century that he hosted NPR’s Morning Edition, sometimes with a bit of whimsy.

[NPR's "Morning Edition" Theme Music]

EDWARDS: Good morning, I'm Bob Edwards. A Cooper's hawk in pursuit of a pigeon flew through an open door into a Home Depot store in suburban Cleveland last week, and has been living in the rafters of the store's 25-foot-high ceiling. It's a bit disturbing to some customers when the bird decides to have lunch, but Cooper's hawks are an endangered species and cannot be harmed. Wildlife experts say the hawk likely will leave the store when it runs out of pigeons. You're listening to Morning Edition, from NPR News.

CURWOOD: In 2006, after he left NPR, Bob produced an award-winning environmental documentary called Exploding Heritage, based in and around his home state of Kentucky.

EDWARDS: The Appalachian Mountains were standing before the Ice Age. They’re nearly 300 million years old. They have survived everything nature has thrown at them. But they might not survive man. [Sound of explosion.] Using a mixture of ammonium nitrate and fuel oil, mining companies are blowing up mountains to get to the valuable coal deep inside.

CURWOOD: Bob Edwards’s interest in environmental journalism also brought him onto the advisory board of Living on Earth back in 1990 when I was starting the show. He gave a lot of help with contacts and encouraged the mission at a time when some in public radio doubted the need for a show dedicated to environmental journalism. Thank you, Bob Edwards, for knowing the stories and telling them.

Ross Gelbspan was a brilliant journalist who wrote for the Washington Post, the Philadelphia Bulletin and the Boston Globe, where he won a Pulitzer Prize for a series he created on discrimination in hiring. He was also my editor and boss when I wrote for the Globe in the 1980’s, and a great teacher and resource for Living on Earth. Ross authored two incisive books about climate change, The Heat is On and Boiling Point. And back in 2002, Ross Gelbspan warned Living on Earth listeners that scientists were increasingly worried the climate could unravel.

GELBSPAN: The latest IPCC Report also said that the climate is changing much more quickly than the scientists had anticipated even a few years ago. So, there’s a very strong note of alarm in the latest IPCC Report. And it’s anyone’s guess as to what the IPCC Report five years down the road will contain.

CURWOOD: Ross Gelbspan summed it all up this way: “Climate change is not just another issue. It is the issue that, unchecked, will swamp all other issues. The only hope lies in all the countries of the world coming together around a common global project to rewire the world with clean energy. This is a path to peace—peace among people, and peace between people and nature.” Thank you, Ross, for your care and brilliant career.

Related links:

- Read Bob Edwards’ Obituary

- Read Ross Gelbspan’s Obituary

[MUSIC: Open Road Folk Music. “Long Summer Day” on Instrumental Indie-Folk, Vol.2, alexrainbirdRecords]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Quentin Bell, Josh Croom, Jenni Doering, Karen Elterman, Swayam Gagneja, Sommer Heyman, Mattie Hibbs, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Sarah Mahaney, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari.

BELTRAN: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments@loe.org. I’m Paloma Beltran.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth