March 22, 2024

Air Date: March 22, 2024

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Personal Care Products and IVF Miscarriage

View the page for this story

A recent study of 1500 women in China found links between personal care product use and in-vitro fertilization problems, including slower embryo development and miscarriage. Pediatrician Leonardo Trasande joins Host Aynsley O’Neill to discuss the findings and the growing evidence linking hormone disrupting chemicals to pregnancy difficulties for people using IVF. (13:25)

Investment Risks from Climate

View the page for this story

Climate disasters, adaptation costs and market shifts threaten the value of public companies that are inadequately prepared for climate change. So the Democratic majority US Securities and Exchange Commission recently approved a rule that will require public companies to inform investors about their greenhouse gas emissions and climate risks. Emeritus Professor Pat Parenteau of Vermont Law and Graduate School joins Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood to explain the rule and the pushback from industry and several Republican-led states. (10:44)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Living on Earth Contributor Peter Dykstra and Host Aynsley O’Neill talk about a study that found safer lead levels in people living in federal public housing versus low-income private housing. Also, a $600,000 sand dune paid for by residents of Salisbury, MA washed away just days after being put in place. And in history they celebrate the birthday of French mathematician Jean Baptiste Joseph Fourier, who first proposed the existence of the greenhouse effect 200 years ago. (04:24)

Orbital: An Earth-Centric Novel Set in Space

View the page for this story

The handful of astronauts and cosmonauts on board the International Space Station float in a strange paradox, with the Earth constantly in view, but always out of reach. The 2023 novel called Orbital explores the splendor of planet Earth as seen from orbit through a day in the life of six astronauts up on the ISS, and author Samantha Harvey joins Host Jenni Doering to discuss her book. (16:22)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

240322 Transcript

HOSTS: Jenni Doering, Aynsley O’Neill

GUESTS: Samantha Harvey, Pat Parenteau, Leonardo Trasande

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

DOERING: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

DOERING: I’m Jenni Doering

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

Some personal care products can worsen the outcomes of IVF pregnancies.

TRASANDE: The more studies like this come out, the more they unravel another layer to the onion, and you realize that embryonic development is a very very vulnerable phase of a child's growth.

DOERING: Also, astronauts on board the International Space Station are far from home, and “home” is a whole planet.

HARVEY: The earth is the answer to every question. The earth is the face of an exalted lover. They watch it sleep and wake and become lost in its habits. The Earth is a mother waiting for her children to return full of stories and rapture and longing.

DOERING: That and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Personal Care Products and IVF Miscarriage

A variety of personal care products, from cosmetics to skin care, have been associated with adverse IVF outcomes. (Photo: Pixabay, Pexels)

DOERING: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston this is Living on Earth. I'm Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

[CLIP FROM CLUELESS]

CHER: Let’s do a makeover.

[GASP]

TAI: No, no…

DIONNE: Aw, come on, let us! Cher’s main thrill in life is a makeover, okay? It gives her a sense of control in a world full of chaos.

CHER: Please??

O’NEILL: If you’ve ever seen the 1995 teen movie Clueless, then you might know the scene where popular girls Cher and Dionne set to work transforming the grungy new girl at school with an arsenal of eyeliner, foundation, lipstick, hair dye, and Coca Cola cans used as hair rollers. Coke Cans aside, putting on a full face is a daily routine for many of us. But we’re all a bit ‘clueless’ about the potential consequences to our health from some of the chemicals in mascara, concealer, and more. What we do know is that the more researchers look for connections between health problems and common cosmetics, soaps, and skin care products, the more links they uncover. These products often contain a slew of endocrine-disrupting chemicals that hack the body’s hormone function and wreak havoc on our reproductive systems. Bisphenol A, or BPA, and phthalates, which can be found in some body washes and shampoos, have been shown to reduce semen quality and negatively impact pregnancy outcomes. Makeup can contain tri-closan and a class of “forever chemicals” called PFOA, which have also been associated with the disruption of healthy pregnancies. And a recent study out of the Tongji region of China followed 1500 women undergoing in-vitro fertilization treatment and asked them how often they used different kinds of personal care products. Statistical analysis showed that the women who used cosmetics just a few times per week after IVF could be twice as likely to miscarry as those who didn’t use any. Joining me now to help us understand the research is Dr. Leonardo Trasande, a pediatrician who directs the NYU Center for the Investigation of Environmental Hazards and was not involved in the study. Dr. Trasande, welcome back to Living on Earth!

TRASANDE: Thanks for having me again.

O'NEILL: So what were the main findings of the research? What did they discover?

Bisphenol A and phthalates, found in many shampoos and body washes, are known to have adverse effects on reproductive health. (Photo: Shora Simasaki, Pexels)

TRASANDE: So when they followed this population, they found that the use of skincare products was associated with a slowing of the maturation of embryos, compared to those that did not use skincare products. And then when they transferred the embryos into the womb, the women who used cosmetics were more likely to miscarry than those who didn't. And then when the researchers looked at gel and soap use, they found some patterns in which there was a slowness of the division rate of the embryo, among younger women, and there was also some changes in the development of certain key parts of an embryo among women with higher weight. So you have multiple threads of evidence coming together with a consistent signal that there's something about this very susceptible window of development that is being disrupted by personal care products.

O'NEILL: And to what extent are the results sort of aligned with what we already know about endocrine disrupting chemicals, and specifically endocrine disrupting chemicals in personal care products? What adds more evidence to what we knew already, and what's new here?

The study found that use of skincare products was associated with slower embryo maturation. (Photo: Polina Tankilevitch, Pexels)

TRASANDE: So there are studies out of colleagues at the Massachusetts General Hospital and the Harvard School of Public Health that have found that when you measure urinary levels of the chemicals that are often found in these personal care products, phthalates, scents that can have sex specific disrupting effects, as well as other adverse effects, in folks who are trying to conceive via IVF, you have delayed pregnancy outcomes, and ultimately, in some cases, more likelihood of miscarriage. And then when you take a population like that and follow the kids themselves, you start to see changes in their health and well being. We already know that children born to in vitro fertilization families have more adverse outcomes. We often thought, well, it's the earlier exposure to contaminants or other factors or genetics, and many reasons, why that couple might be having difficulty conceiving in the first place, which is why they need in vitro fertilization. But those studies at Mass General Hospital and other places across the planet have identified a consistent pattern in which this is an especially vulnerable population almost to a second hit. And that second hit reverberates even more loudly than we do see when the same exposure occurs in folks who don't have in vitro fertilization as the method of pregnancy. But this is a very valuable study in that it adds to the base of evidence suggesting that a population that is likely to be vulnerable to chemical effects can be disrupted at a very crucial window of embryonic development. That embryo is going to divide and divide and divide all the way in to eventually, hopefully, making you a human being.

O'NEILL: One thing that caught my eye is that the study talks about extremely broad categories. It's skincare products, gel and soap, cosmetics. We're not talking specific brands or even really specific products. What do you make of the aspect of that research design in that we're looking at such ambiguous categories?

TRASANDE: That's the grain of salt that has to be put in there. So that introduces what we call exposure imprecision, which literally means you can't precisely evaluate what the exposure is that's causing the potential harm. Now, most statisticians will tell you that when you have that kind of imprecision, it actually makes it harder to find an effect. So that's why I think it's all the more remarkable that you see something and multiple signals, frankly, here.

O'NEILL: As you acknowledge this is a vulnerable population already. And then there's a bit of ambiguity when it comes to this term of personal care products. What else sort of needs to be taken into account when drawing a conclusion from this study?

For the women in the study, the odds of experiencing a miscarriage was higher among those who reported using cosmetics just a few times a week compared to those who didn’t use cosmetics at all. (Photo: Skitterphoto, Pexels)

TRASANDE: That's a completely fair question because the population is from one part of the world. It happens to be from a part of the world where they have a track record of following populations extremely carefully, and providing valuable insights that as an American researcher, I have difficulty pulling off. And then the products used in China, in this region of China, mind you, might not even be representative of the entirety of China. Look at Europe and the United States, for example. The Food and Drug Administration has only banned 11 or so chemicals in personal care products and cosmetics. The European Union has banned over 1300. So when you use a personal care product, simply by virtue of taking a flight across the pond, you have a difference in what your exposure pattern is. That's an important nuance to point out in addition to the fact that this population isn't representative of the United States, there may be different genetics and other coexisting environmental and social factors involved.

O'NEILL: Dr. Trasande, what further questions does this study bring up for you? Where do you see this science, these investigations going from here?

TRASANDE: So coming into the field of environmental health, I, as a pediatrician, was always focused on pregnancy and early childhood, as windows of susceptibility to toxic exposures. But the more studies like this come out, the more they unravel another layer to the onion. So exposures when we measure them in pregnancy are typically, you might get first trimester exposure, you really might get second trimester exposure in many cases. But a study like this, that starts to look at what you might call the embryonic phase of exposure, you get a more refined window of when things might be toxic to a child's development. And you realize that embryonic development is a very, very vulnerable phase of a child's growth. But then the more you unravel the onion, the more you realize, whoa, this is a bigger and more complicated story than you might be able to deal with fully in a lifetime. And that is because the oocytes and sperm cells that make humans living today, were the byproduct of a parent who themselves had their ovaries and testes developing during their in utero development in their grandparents' phase of life. So exposure two generations back may have consequences that only appear now.

Dr. Trasande says this study shows that the embryonic phase of development is extremely vulnerable to chemical exposure. (Photo: MART PRODUCTION, Pexels)

O'NEILL: So even with the caveats that we've discussed, this study does add a piece to the endocrine disruption puzzle. I think it's safe to say that the vast majority of people use personal care products in the categories of skincare, soap, cosmetics, at least some time in their life. So what in the world can be done for those who are concerned about the endocrine disrupting chemicals that might be in their products?

TRASANDE: So the great news is that this doesn't require a PhD in chemistry, and it doesn't have to break the bank. The study I use often to drive this point home is from an agricultural community in California, relatively low socio economic status, in which they simply read the label. And teens were told, teen girls were told, not to use products with fragrances or phthalates. They dropped their levels of phthalates in urine and other related endocrine disruptors in three days. Three days.

O'NEILL: Wow.

And that's the short term readout. In the medium term, in weeks, at most, you see changes in hormone levels. In the longer term, you can see benefits accumulating in the form of reductions in chronic disease. So there are short, medium, and long term consequences to continuing to change behavior, regardless of what disease or disability or exposure pattern you had in the past. And regardless of all the exposures you've had in the previous generations that I talked about. Now, in this very app-ified world we live in, the good news is there's also an app for that. Environmental Working Group has an app called Skin Deep that I like very much, very clear communication scoring system 1 to 10, green lights, yellow lights, red lights, things that make it easy to discern which products have which chemicals of concern.

O'NEILL: Dr. Trasande, what are you hoping will come out of the publication of the study?

Dr. Leonardo Trasande is a pediatrician who directs the NYU Center for the Investigation of Environmental Hazards. (Photo: Cheryl Stockton)

TRASANDE: So we can start with awareness. In addition, we do need more of research. And I know that that's a cop out for most researchers to bring up. But there's studies on the way that are trying to evaluate preconceptual exposure in a systematic way across the United States. That's a program I'm privileged to be part of called the Environmental Influences on Child Health Outcomes program, that is trying to do a preconception study largely with women who just had a baby. And there are other studies on the way that are trying to bring populations who may or may not be planning a pregnancy. And that's the challenge, because reproductive choice is real, and people are deciding when or when not to have a pregnancy. And in that regard, it can be hard to identify or even have people acknowledge that they're trying to have a pregnancy, and so they may not participate as readily in these kinds of studies. So the design is challenging, but it's important to do because what we need to do is to measure these exposures, be it by questionnaire that this study did in China, or using biological measures.

O'NEILL: Dr. Leonardo Trasande de is a pediatrician who directs the NYU Center for the Investigation of Environmental Hazards. Dr. Trasande, thank you so much for your time today.

TRASANDE: It's always a pleasure, Aynsley. Thanks again.

Related links:

- Frontiers in Endocrinology | “Associations of Personal Care Products Use With Reproductive Outcomes of IVF/ICSI Treatment”

- National Institute of Health | “Environmental Influences on Child Outcomes (ECHO) Program”

- Download Environmental Working Group’s Healthy Living App with Skin Deep Database

- Environmental Health Perspectives | “Urinary Phthalate Metabolite Concentrations and Reproductive Outcomes among Women Undergoing in Vitro Fertilization: Results from the EARTH Study”

- Fertility and Sterility | “Maternal and Paternal Preconception Phthalate Exposure and Birthweight of IVF Singletons”

[MUSIC: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Stephen Kovacevich, London Symphony Orchestra, Sir Colin Davis, “Mozart: Piano Concerto No.21 in C, K.467 -2. Andante” on Mozart, UMG Recordings]

DOERING: When we come back, risky business in a warming world. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Stephen Kovacevich, London Symphony Orchestra, Sir Colin Davis, “Mozart: Piano Concerto No.21 in C, K.467 -2. Andante” on Mozart, UMG Recordings]

Investment Risks from Climate

The new SEC rule will require companies to be more transparent about their greenhouse gas emissions and the climate-related financial risks they face. (Photo: Richard Bett, Flickr, Public Domain)

O’NEILL: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

During the Great Depression President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed into law the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, to help safeguard US financial markets against collapses like the Wall Street Crash of 1929. That was decades before scientists alerted the world to the problem of climate disruption, which is creating new financial risks because of just how expensive it is. Climate disasters now cost the US around $100 billion every year. And adapting to sea level rise, extreme heat and hurricanes requires significant and costly upgrades to infrastructure and buildings. The climate emergency mandates a rapid shift towards cleaner energy, bringing new economic opportunities but also tanking the value of fossil fuel assets. So the financial regulatory body that was created by FDR recently approved a rule that by 2026 will require public companies to inform investors about their greenhouse gas emissions and climate risks. The three Democrats on the Securities and Exchange Commission all voted for the climate disclosure rule while their two Republican colleagues voted against it. The fossil fuel industry immediately pushed back against the rule and filed several lawsuits with the help of conservative states, resulting in a temporary stay by the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals. The opposition is part of a broader challenge by Republicans to the right of agencies to regulate on the environment, from protecting fragile wetlands to setting air pollution standards. Pat Parenteau, Emeritus Professor at Vermont Law and Graduate School, joined Living on Earth Host Steve Curwood to explain the SEC rule and the pushback.

CURWOOD: So what exactly is this SEC rule? And what does it require? And why is it such a big deal?

The SEC recently backed off from requiring disclosure of Scope 3 emissions. Scope 3 emissions refers to greenhouse emissions by the end consumer, like when people burn gas in their cars. (Photo: Erik Mclean, Unsplash)

PARENTEAU: Right, so it's requiring for the first time that companies disclose their greenhouse gas emissions, and also their plans for addressing the threats and the financial risks, that climate change poses, that's a variety of risks, physical risks to their assets and their facilities, transition risks, because we're moving out away from fossil fuels into new forms of energy and transportation, liability risks, from the lawsuits that have been filed by states and counties and cities across the country, and even indeed, across the world, reputational risks and so forth. So, this rule for the first time is telling these companies that they have to be more forthright in what their emissions are, and also what they're doing about it, and also how much they're spending, and what the value of their assets are going forward and so forth.

CURWOOD: Now why is the Securities and Exchange Commission, the SEC, allowed to do this? I gather, it covers publicly traded companies. But what's the rationale that they could regulate this?

PARENTEAU: Yeah, the rationale is that they have to ensure that investors have accurate information about the value of the companies they're investing in, and the risks the financial risks that companies are facing. The opponents of the rule are claiming it's just climate policy or environmental policy. SEC is saying no, it has to do with financial risks. And so therefore, the real question is going to be is SEC within the scope of its authority as given to it by Congress from really the 1930s when the Securities and Exchange Commission Act was passed.

The new rule quickly faced legal challenges from the fossil fuel industry. (Photo: AP, Pexels)

CURWOOD: So, this will be settled in court, although one would think that the SEC has the right to raise the question of these companies going to be viable going forward given the climate emergency?

PARENTEAU: Well, that's right. And it isn't the first time actually that the SEC has addressed both environmental issues generally, and the risks of pollution and liability for pollution, oil spills, for example, which can have major billion dollar consequences. Nor is it the first time that the SEC has issued guidance on climate risks. This is the first time they've actually adopted a rule that has the force of law with penalties for non-compliance. So it's definitely a step up from where SEC has been before, but it's not brand new.

CURWOOD: Now, as this rule was getting put together, there were a number of things that were eliminated from the proposed rule that what was finally published, what was changed? And how does that by the way, compared to what's going on in Europe and what California is doing?

Compared to the new SEC rule, emissions disclosure requirements are more rigorous in California, which has the fifth largest economy in the world. (Photo: Peter Miller, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

PARENTEAU: Right. So the proposed rule went all the way to require disclosure of emissions associated with the company's supply chains and with their end use by consumers, that would be us right? People that go to the gasoline station and pump the gas of Exxon and BP and Shell and so forth. It's called Scope 3 emissions, and they comprise the largest percentage of emissions attributable to these companies. But they are extremely difficult to assess and quantify, because, of course, you're talking about literally millions and millions of consumers using these products. So the SEC backed off from requiring disclosure of these so called Scope 3 emissions. You mentioned that companies are already subject to these disclosure requirements that are more rigorous than what the SEC has proposed in California for companies doing business there, California being the fifth largest economy in the world, and also companies doing business in Europe, where the European Union has imposed even more rigorous disclosure requirements. So in many ways, this is not new to these companies. They're either doing it or they're being required to do it in other contexts. The SEC did a couple of other things to water down the final rule. One, they increased the number of companies that are exempt from any disclosure requirements. So now they're just focused on really the largest companies in the world that trade publicly. And they also gave to companies the option of determining whether the risks from climate related disasters are material to the individual companies. That introduces a sort of wildcard into this equation when you have to have individual companies determining: Do we consider the risks to our business plan material enough to disclose to the public?

CURWOOD: Wow, I think the analogy is having the fox have the keys to the henhouse.

PARENTEAU: Yeah. Right the foxes, making sure the chickens are all safe and secure. There is oversight, so once the determination is made, that a company has acknowledged or been told by the SEC, that it's facing some material risks, that calculation of you know, the quantity of the emissions, the level of threat from the physical impacts of climate change, those kinds of things have to be independently verified. That's going to introduce yet another level of analysis for investors to protect them from investing in really risky assets. The danger of stranded assets, if companies don't seriously start moving away from fossil fuels, a lot of the assets on their books are going to be stranded assets, and investors will be left holding the bag.

CURWOOD: Stranded assets such as an untapped oil field that they'll never be able to use.

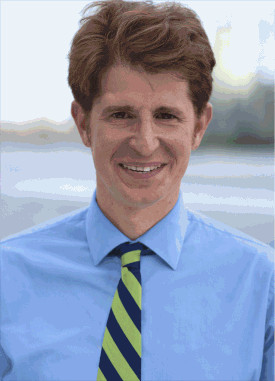

Pat Parenteau is emeritus professor of law at Vermont Law School and formerly served as EPA Regional Counsel. (Photo: Courtesy of Vermont Law and Graduate School)

PARENTEAU: Yes.

CURWOOD: Pat, as soon as this rule was filed, lawsuits were also filed by industry. And I gather that one of those lawsuits has advanced at the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, which has granted their motion to stay the rule. What is the practical effect of these lawsuits? And ultimately, what do you think it says about the ultimate fate of this rule the way that that court has responded to saying, stop?

PARENTEAU: Right, so there have been now lawsuits filed in six different US Courts of Appeal. The Republican attorneys general from 13 different states have filed these cases. And the Fifth Circuit, which is the most conservative court in the country right now, you might argue that Supreme Court itself is the most conservative, but certainly among the courts of appeals. The Fifth Circuit is pro industry, pro oil development, in particular, sits in New Orleans, Louisiana, did issue a stay on the SEC rule. It was a one line order, no explanation. This stay by the Fifth Circuit, will be in existence for a very short period of time. So its practical effect is limited. Because what happens now is there's a special panel, which will draw lots from a lottery to determine which of these six circuit courts where these cases are pending, will actually hear the case. Maybe it'll be the Fifth Circuit, maybe it'll be one of the other circuits. I don't think the stay order says anything about whether the rule survives. And, in addition to those challenging the rule as being outside of the SEC is authority. There is also challenges from the environmental side, saying the SEC erred by dropping the requirement for considering these so called Scope 3 emissions. And that case is pending in the DC Circuit Court of Appeals. And also in the Second Circuit Court of Appeals. Both of those circuits, have a majority of Democrat appointed judges, whereas the other circuits have a majority of Republican appointed judges. So you can see even in the context of where is this case going to be heard, and who is going to hear it and decide it, politics is playing a role in the ultimate fate of the rule itself.

DOERING: That’s Emeritus Professor Pat Parenteau of the Vermont Law and Graduate School, speaking with Living on Earth Host Steve Curwood.

NOTE: After we recorded our interview the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals was designated as the court to hear the challenges to the SEC rule.

Related links:

- Learn more about the SEC’s Adopted Rule

- Reuters | “US Climate Rule Will Boost Sustainable Accounting Industry”

- Wall Street Journal | “U.S. Appeals Court Temporarily Halts SEC Climate-Disclosure Rules”

[MUSIC: ABBA “Money, Money, Money” on Money, Money, Money, by ABBA, Polar Records]

Beyond the Headlines

Lead exposure can lead to harmful health effects including neurological issues. A recent study found that individuals currently receiving federal housing assistance in the United States had blood lead levels that were 11.4% lower than those of other low-income individuals. (Photo: National Cancer Institute, Unsplash)

O'NEILL: It's the time in our broadcast where we want to take a look at some stories from beyond the headlines. And for that we need Living on Earth contributor Peter Dykstra. He's on line now from Atlanta, Georgia. Hey there, Peter, what do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Oh, hi, Aynsley. There's a study in the journal Environmental Health Perspectives that brings us some good news in an area we really don't expect it. Blood lead levels for residents in federal housing were 11% lower in a recent study than those of other low income residents living in private housing. The reason for this is that federal housing has taken strong action to reduce lead paint. And it's shown positive results. And of course, lead is a huge problem, because it impacts neurological systems, particularly those of young kids.

O'NEILL: I feel like there's always something going wrong when we talk about government housing programs. So it's nice to hear some good news for once.

DYKSTRA: It is, and there's still plenty going wrong with government housing and housing in general. But this is good news, particularly in low income housing that tends to have a bias toward people of color.

O'NEILL: Hopefully, the government can take a page out of their own book when it comes to regulating private landlords and housing companies and get some progress on lead exposure in those homes as well.

DYKSTRA: Right and it may take government action there because slumlords are rarely inspired to do the right thing on their own.

O'NEILL: Sadly, all too true. Well, what else do you have for us this week, Peter?

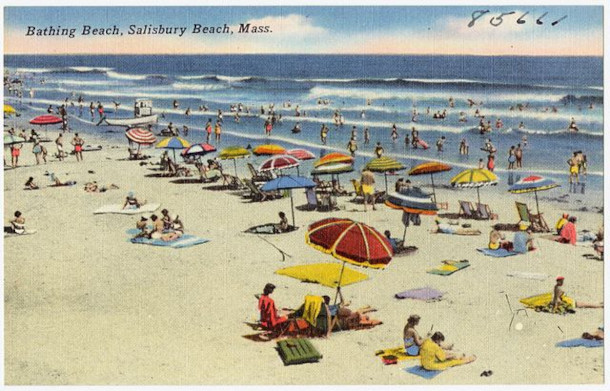

Salisbury beach in Massachusetts, long a popular destination for beachgoers, is now threatened by rising sea levels. Residents spent about $600,000 on sand to protect the beach in early 2024, only to have the protective dune wash away in a winter storm days after it was completed. (Image: Boston Public Library Tichnor Brothers collection, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

DYKSTRA: We go from some good news in low income housing to some potentially bad news for high income housing, specifically Salisbury, Massachusetts. That's a town north of Boston with a beautiful stretch of beach. That beach is lined with million dollar homes, and they have a beach problem. Not the usual beach problems we hear about from spring breakers or sharks, but it's the beach itself, which is washing away. That's what barrier beaches do. But with sea level rise, it's happening quicker and these million dollar homes are threatened.

O'NEILL: Well barrier beaches, if they're always washing away, what's the news story here, Peter?

DYKSTRA: The residents looking at the beach disappearing, having coped with storms, are now looking at more frequent storms from climate change. They're looking at sea level rise. And so private homeowners trucked in $600,000 worth of sand to protect their eroding beach. And that sand, expected to last at least a few years, was gone in a single weekend storm.

O'NEILL: Wow, that is a lot of sand and a lot of money lost in one storm. What else can they do, Peter?

DYKSTRA: Well, when you have million dollar homes, and the beach is gone, you no longer have a million dollar beach home. It's something that has no real solution. A lot of our sandy beaches are disappearing or are going to disappear. Climate change is making that just a quicker phenomenon.

O'NEILL: Well, Peter, before we let you go, it's time for you to tell us what happened in history this week.

The French mathematician Jean-Baptiste Joseph Fourier (b. March 21, 1768) studied heat flow and is often considered the first scientist to describe what we now know as the greenhouse effect, though he didn’t name it that. (Image: Artist Julien-Léopold Boilly (1796–1874), Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

DYKSTRA: Certainly. On March 21, 1768, a mathematician and physicist named Jean-Baptiste Joseph Fourier was born in France. In the early 19th century, specifically 1824, 200 years ago, he authored the first of two papers that looked into the possible origins of the greenhouse effect, because he wondered why the Earth, some 93 million miles on average away from the Sun, stayed so warm and how the planet's atmosphere trapped solar heat.

O'NEILL: Two centuries and we've been building off that knowledge ever since. Happy birthday to Jean-Baptiste Fourier.

DYKSTRA: Happy birthday indeed.

O’NEILL: Well, Peter, thanks as always for taking us beyond the headlines. Peter Dykstra is a contributor to Living on Earth and we'll talk to you again soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, Aynsley, thanks a lot and we'll talk to you soon.

O'NEILL: And there's more on these stories on our website. That's LoE.org.

Related links:

- Read the study about federal housing and blood lead levels here

- WBUR | “Salisbury, Mass. Spent $600K on Shore Protection. A Winter Storm Washed It Away Days Later”

- Learn more about Joseph Fourier

[MUSIC: Visual Melodies-John and his family, “French Music-France Travel Video Uplifting Instrumental Music” by Visual Melodies, available on the Visual Melodies channel - www.VisualMelodies.net]

DOERING: Coming up, a novel explores the sixteen sunrises a day aboard the International Space Station. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Visual Melodies-John and his family, “French Music-France Travel Video Uplifting Instrumental Music” by Visual Melodies, available on the Visual Melodies channel - www.VisualMelodies.net]

Orbital: An Earth-Centric Novel Set in Space

Orbital by Samantha Harvey is a fictional novel about twenty-four hours in the lives of six astronauts aboard a space station orbiting earth. (Photo: Courtesy of Grove Hardcover)

O’NEILL: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Aynsley O’Neill

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

At any given moment there are a handful of humans orbiting the Earth aboard the International Space Station. These astronauts and cosmonauts live in a strange paradox. For them the Earth is constantly in view, but always out of reach. They carry photographs of loved ones to keep them close, but these astronauts are still orbiting 250 miles up. Tethered emotionally and by the pull of gravity to the only home our species has ever known, they become each other’s family for six to twelve months. A new novel called Orbital imagines a day in the life of six astronauts up there as they circle the Earth every 90 minutes. Author Samantha Harvey joins us now to discuss. Welcome to Living on Earth!

HARVEY: Thank you, Jenni. It's my pleasure to be here.

DOERING: So Samantha, could you start us off by reading a passage from the beginning of your novel Orbital?

HARVEY: Okay. "Rotating about the earth in their spacecraft they are so together, and so alone, that even their thoughts, their internal mythologies at times, convene. Sometimes they dream the same dreams — of fractals and blue spheres and familiar faces engulfed in dark, and of the bright, energetic black of space that slams their senses. Raw space is a panther, feral and primal; they dream it stalking through their quarters. They hang in their sleeping bags. A hand-span away beyond a skin of metal the universe unfolds in simple eternities. Their sleep begins to thin and some distant earthly morning dawns and their laptops flash the first silent messages of a new day... Some alien civilization might look on and ask: what are they doing here? Why do they go nowhere but round and round? The earth is the answer to every question. The earth is the face of an exalted lover; they watch it sleep and wake and become lost in its habits. The earth is a mother waiting for her children to return, full of stories and rapture and longing. Their bones a little less dense, their limbs a little thinner. Eyes filled with sights that are difficult to tell."

Orbital features descriptions of fictional astronauts performing experiments, reconstituting dehydrated meals, and living an astronaut’s daily routine on a space station. (Photo: NASA, NASA.gov, public domain)

DOERING: In that passage you just read from the introduction, you have this line, "The earth is the answer to every question. The earth is a mother." And one thing I just loved about this book is how central of a role Earth plays in it despite the fact that this is set in space. Most space novels are about escaping Earth's gravitational pull entirely. What made you decide to write a book like this?

HARVEY: Well, I think you sort of hit the nail on the head in that for me, this was always about the Earth more than it is about space. I think it's really interesting and mind blowing to look out at the cosmos and to see it from that vantage point of low Earth orbit. So it wasn't that I didn't find that interesting. But the thing that I wanted to focus on was the view of the Earth, because it's so singular from that vantage point because 250 miles up isn't actually very far, you know. You don't get an entire view of the Earth, you just see the sort of a limb, the Earth's limb, kind of rounding away beneath you. And you can see... not detail. You can't see traces of humanity. And I think that's very interesting. But you can see the natural world. You can see the continents. You can see forests. You can see desert. Obviously ocean, you can see the different types of ocean, that the oceans in different climates across the world, the different colors, the different blues and greens. And I think that distance is both intimate and panoramic and distant. I think is a very sort of kind of paradoxical vantage point to write from. And that's what interested me about it, that it's so intimate, such an intimate view of our planet. You're not far from it, It's kind of tenderly, the space station is tenderly circling this planet. And yet, of course, it's detached from it. It's outside of its atmosphere. It has a different view to any view we could have on Earth. And I think that that contradiction, that sort of bashing together of different perspectives is really interesting to me.

DOERING: Now, Orbital is built around the 16 sunrises and sunsets that these astronauts see in a 24 hour period as they orbit the Earth 16 times per day. And it seemed to me that this structure mimics some of the themes in the book. How did you decide on this really short, narrow timeframe?

HARVEY: Yeah, it didn't come to me at first, actually, that in the first draft, the book was written over a month. And I wrote it from the point of view of just one of the astronauts, and I found that I couldn't say what I wanted to say. I knew that it was a novel I wanted to write, but I couldn't find the means to say the things I wanted, to get to the heart of what I wanted to say. And I was getting bogged down in the repetition of breakfast times and lunchtimes and dinner times over a month. I knew that I wanted to talk about time, the way time has exploded in space. And it occurred to me, after a conversation with a friend actually about the book that I needed to be cleverer about it. I needed to use the structure of the book to say some of things I wanted to say about the dislocation, that disorientation of being in that environment and the fact that you're going around the Earth every 90 minutes. And then it just became perfectly obvious to me that it should be one day, 16 sunset, 16 sunrises that we, as the reader should experience and the book should try in some way to simulate the experience of going around the earth and how one day really just can't feel like one day in many ways. So as soon as I decided on that structure, the whole thing fell into place and everything aligned, and I rewrote it very quickly. And the book shrunk as a result, and it's compressed down to the length it is now which is quite short. So it suddenly began to work. I could make it do the things I wanted to do. I could focus on the imagery, on the sense of time on the dislocating experience of being there without having to contend with endless kind of domestic concerns about their daily schedule over a month.

DOERING: You have this line in your book, "Space shreds time to pieces." I love that.

Astronauts eat food far more typical than the space ice cream found in many museum gift shops. (Photo: NASA, NASA.gov, public domain)

HARVEY: I mean, obviously, I don't know what it's like to be in space. But if you even watch videos of the Earth, of the ISS orbit online, on the NASA website, or YouTube or whatever, you feel this kind of steady progression of the craft around the planet and the rapidity of the sunrise coming upon you. It's dark, and then suddenly, this light rushes across the face of the earth, in a sort of biblical way, that takes your breath away, even watching it on a video, and suddenly it's daylight, and you're in a different continent. And what do you do with that, as someone who's in orbit, experiencing that and when your space agencies are tethering you to a 24 hour clock. And they're trying to structure your days quite rigidly around a 24 hour clock, but nothing that you're experiencing out of the window is reinforcing that. So again, the weird dissonance between the time that is imposed on you from the ground and the time that you're experiencing space creates a sort of weird limbo that you have to somehow function in. So I wanted to imagine what that might be like. And, of course, it is only my imagination.

DOERING: Right? I mean, you know, I've never been up to space. You've never been up there. And yet, you're able to really delve into what it might be like, as an astronaut on the International Space Station. You talk about everyday life and even how they clean the toilets. So how did you go about researching such a unique experience?

Orbital takes place on a fictional version of the International Space Station. In the book, there are six astronauts and cosmonauts from America, Russia, Italy, Britain, and Japan. (Photo: NASA/Roscosmos, NASA.gov, public domain)

HARVEY: Well, actually, it isn't hard to research this subject, because there's so much information about it. I don't know if you've ever spent very long or any time on the NASA website, but is a deep labyrinth of a place. You can spend a lifetime there. And it has so much information about all aspects of what NASA is doing, but particularly the ISS. I read books by astronauts. I watched endless material films and videos made by astronauts. I did countless online tours of the space station. And everything is there to be found out. And then you get the more kind of niche material. I downloaded the ISS Maintenance Manual [LAUGH] and understood, probably 4% of what I was reading. That's probably generous, probably less than that. But I could get a sense of how many moving parts there are and how much maintenance it requires. And then once I was started, I continued to research the subject throughout the writing of the book. So that became a weaving together of research and imagination and allowing the two to sort of exist in a dance together and to constantly feed one another.

DOERING: And as the astronauts up there orbiting the Earth 16 times a day, they watch this typhoon that's traveling across the Pacific Ocean and building in the Pacific Ocean, and then gathering strength. This is the only disaster that happens in the book. It's on earth, not in outer space. Why was this important to include?

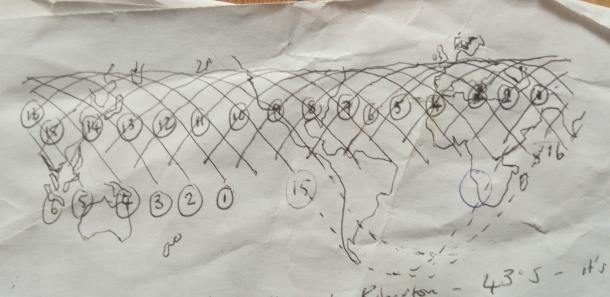

The map of the ISS’s orbit that Samantha Harvey made and referenced while writing Orbital. It was eventually turned into the map included in the front of the book. (Photo: Samantha Harvey)

HARVEY: I wanted something that would kind of mark out time in the book in a straightforward way. So from the beginning, I thought that would probably be a large weather event of some kind so something that is inexorably moving across the earth. And in this case, it's a typhoon that is moving toward the Philippines. Also, I wanted to get to the beauty of some of these weather events from space. And again, the contradiction of that because we know the destruction, they cause on earth but from space they're quite beautiful and mesmerizing. And you can really see the way the weather shifts about the surface of the earth and how the rotation of the earth is pulling the winds and spirals. And I wanted to be able to write about that because it's just actually very inspiring to watch. And also, we know that there are increased weather events, that weather is getting more extreme because of climate change. So I wanted to be able to speak to that without having to make any great claims or lectures on the state of the planet and of climate change. But to be able to say, look, here's something that is happening more frequently. It is something that astronauts see from space quite regularly. It is beautiful; it is magnificent; it is destructive and terrible. And I wanted to be able to hold both of those views in place at the same time, that worldly view and the view from space.

DOERING: It is a really interesting way to be able to observe and sort of comment on what's happening with the earth right now with the climate crisis. Because it is this thing that's so big and huge, that it's usually hard for us to like, even conceive of what's happening. But you're able to narrow this down to a 24 hour period, and to the six astronauts and their perspective. And like watching them, watch this typhoon in the Pacific.

HARVEY: It's hard to know how to think about climate change. It's one thing to sort of intellectually understand what's happening. But to get a grasp on that emotionally or visually, is quite difficult. And I think this was one way of me doing that. And I didn't want this book to be a climate change novel. My motivation was quite different. My motivation was actually to write about beauty and to write about rapture and joy and the splendor of this planet that we live on, you know. I wanted to convey something of what I feel when I look at images of the Earth from space. So I think part of what is implied by looking at the Earth from space and what is implied by its beauty is also the way that beauty is being compromised. And climate change is held within that distanced view of the Earth. It is there to see. And there's a passage in the book in which I sort of talk about that a little bit about how actually, it seems at first, when you look down, it's this kind of humaneness, innocent, unblemished sphere, actually, when you know what to look for, you start to see the signs of mankind, even though you can't see mankind itself, you see signs of it, and of what we are doing to the planet. And that is just a fact of that viewpoint. So it seemed a way of holding the whole view there in front of me at once and just writing about it with a sort of an honesty and sincerity with an eye on its beauty. And to let the rest be implied and to let the reader make of that what they will. And it's just trying to hold a view of the Earth, to the reader to myself, and say, "This is what we have. This is the magnificent thing we have. What do we make of it?"

Samantha Harvey is the author of Orbital and five other books. (Photo: Matt Lincoln)

DOERING: I certainly felt like the Earth is this mother as you write, but it's also really fragile. And it's also this pale blue dot that we can see in this tiny dot in that picture that Voyager took as it turned back towards Earth. At the end of writing this book, how fragile did you feel the earth is? Or did you come away with more of a sense of just how massive and grand it is?

HARVEY: It's interesting when I was writing the book, and I was trying to come up with the descriptions for the earth, you know, obviously things like fragility come up a lot. And it seems like it's made of ether, or it seems like it's made of glass. And it seems rather tiny, because you can orbit it 16 times a day. It's actually not very big. You're in Asia, and suddenly, you're in Australasia, and then suddenly you're in North America, and it hasn't been very long. And the more you watch the videos of these orbits, the more you just become very used to the view. It's like, oh, yeah, there's the East Coast of America. Oh, yeah, there's Central Europe. There's Southern Africa. And it all becomes very familiar, almost like a park, you walk in every day. You come to think of the Earth as quite a small thing. But then at the same time, it's huge. You can't see any manmade objects by day, you know. They just vanish in the immensity of the natural landscapes. And I think in the end, what I came to understand was, the Earth is small, but it's not vulnerable. It's not fragile. It's a lump of rock in space. It will outlive us. We are the vulnerable things — the living things on this planet, the plants, the animals,. It's us we need to think about. I think there's a bit too much talk when we think about climate change of protecting the earth. And I think that's a very abstract way of looking at it. You know, actually, we're trying to protect ourselves and the other creatures that we are fortunate enough to share a planet with. That's what's at stake. We must protect the beings, the... all the living things on this earth, that's our priority. The earth is going to prevail, anyhow.

DOERING: Samantha Harvey is the author of Orbital and five other books. Thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

HARVEY: Thank you. It was my pleasure.

Related links:

- Purchase Orbital and support both Living on Earth and local bookstores.

- Explore the International Space Station.

- Read more of Samantha Harvey’s work.

[MUSIC: Gustav Holst, Berliner Philharmoniker, Herbert von Karajan, “The Planets, Op. 32: 7. Neptune, the Mystic, Deutsche Grammophon GmbH, Berlin]

O’NEILL: Next week on the show, we can now peer deeper into space and farther back in time, than ever before thanks to the James Webb Space Telescope. It’s helped scientists discover very distant and faint black holes.

MAIOLINO: Despite being intrinsically luminous, being so far away it becomes very weak, because it has to travel so much throughout the universe. And that's where the James Webb Space Telescope essentially made this possible. Because it's being the largest telescope in space, with its very large mirror, it can actually collect enough light, even from the most distant part of the Universe, to make the light and the signature of these processes detectable with its instrumentation. It has several fantastic features. But what makes Webb really unique is its sensitivity. It observes primarily in the infrared. And in this band, its sensitivity is orders of magnitude better than any previous facility. Just to give you an idea of the magnitude of the leap, it is equivalent in the visible as suddenly upgrading Galileo's telescope to the modern large telescopes, compressing 400 years of discoveries in the 10, 20 years of operation of James Webb. So we are really making a gigantic leap in the discovery space and in our understanding of the universe.

O’NEILL: We’ll travel 13.3 billion years back in time, next week on Living on Earth.

O’NEILL: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Josh Croom, Karen Elterman, Swayam Gagneja, Sommer Heyman, Mattie Hibbs, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Sarah Mahaney, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments at loe dot org. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth