March 29, 2024

Air Date: March 29, 2024

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Charging Up U.S. Electric Vehicle Markets

/ Jim MotavalliView the page for this story

China’s electric car sales are in the fast lane and lead the world while the U.S. EV industry lags. Although Biden administration policies are designed to jumpstart EVs, a partisan divide on EVs is slowing adoption. Jim Motavalli writes for Autoweek and Barrons and joins Host Aynsley O’Neill to explain what’s going on with the U.S. EV industry and why the future looks bright. (13:14)

Sewage Sludge Danger

View the page for this story

Millions of acres of cropland in the U.S. may be contaminated from PFAS-tainted sewage sludge spread on fields as fertilizer. These “forever chemicals” are taken up by plants and then consumed by livestock and people, making them sick. Kyla Bennett of Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility (PEER) joins Host Jenni Doering to reveal the invisible threat of PFAS in our food and discuss why she believes EPA has failed its mission to protect the public. (18:00)

BIRDNOTE®: The Birds of Yoga

/ Trisha MukherjeeView the page for this story

Bird-inspired yoga poses, from eagle to crow to peacock pose, have deep roots in Hindu mythology and philosophy. BirdNote®’s Trisha Mukherjee explains. (02:03)

From the History Books

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Living on Earth Contributor Peter Dykstra shares a couple of notable items from this week in history with Host Aynsley O’Neill, including the 1971 startup of the first nuclear reactor at Fukushima Daiichi and the 1970 release of environmental classic “Big Yellow Taxi” by Joni Mitchell. (02:23)

Black Hole Breakthrough

View the page for this story

An international team of astronomers recently reported the discovery of a 13 billion-year-old black hole, to date the oldest ever observed, thanks to the powerful James Webb Space Telescope. Lead author Dr. Roberto Maiolino joins Host Jenni Doering to explore new questions about how these mysterious, extremely dense objects form and grow. (09:24)

Star Sounds

/ Aynsley O’NeillView the page for this story

NASA turned infrared, optical, and x-ray data from space into sound in a process called “sonification,” so we can “hear” the gorgeous spiral galaxy known as the Phantom Galaxy. And within our own Milky Way galaxy is the Jellyfish Nebula, the remnant of an exploded star. Host Aynsley O’Neill walks us through these otherworldly sounds. (01:44)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

240329 Transcript

HOSTS: Jenni Doering, Aynsley O’Neill

GUESTS: Kyla Bennett, Roberto Maiolino, Jim Motavalli

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Trisha Mukherjee

[THEME]

DOERING: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

DOERING: I’m Jenni Doering

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

China is racing ahead of the US with EV sales. But don’t count us out just yet.

MOTAVALLI: I think we're going to end up in the same place as China. It might take a little longer, but we're all heading in the same direction. The world is basically moving towards a situation where there will be no new gas cars sold by 2035.

DOERING: Also, treated sewage used as fertilizer is full of toxic chemicals.

BENNETT: I often make the analogy between climate change and PFAS contamination. If we stopped emitting it tomorrow, the amount of PFAS in our water, our soil and our food is going to stay pretty level for hundreds of years or longer before it starts coming down, which is why it's important for EPA to act now.

DOERING: That’s this week on Living on Earth. Stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Charging Up U.S. Electric Vehicle Markets

The Nissan Leaf, priced around $30,000 in March 2024, is one of the cheapest electric vehicles available in the US. (Photo: Benespit, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

DOERING: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I'm Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

China's electric car sales are in the fast lane, leading the world with 7.7 million sold in 2023. And China is sending its EVs abroad, too. The US Energy Information Administration reports that China was responsible for 35% of global EV exports in 2023. That’s in stark contrast to the United States, where automakers like Ford are tapping the brakes on production of the F-150 lightning pickup truck and other EV models. Compared to Chinese drivers, US consumers overall have been slower to switch to electric vehicles. And in this country, where politics drive so much of the conversation, especially during an election year, attitudes towards EVs notably differ across party lines. A 2023 Pew Research Center survey found that 70% of Republican-leaning adults are not likely to consider electric with their next car purchase, while 56% of Democrat-leaning adults were somewhat or very likely to consider an EV. So to help us make sense of the future of electric vehicles, I’m joined now by Jim Motavalli, who writes about green transportation for Autoweek and Barron’s. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Jim!

MOTAVALLI: Great to be on.

O'NEILL: Now I understand that in China, over a third of all the cars that were sold last year were electric vehicles--EVs--assuming that you include a plug-in hybrid in that category. And in the United States, it was less than 10%. Why do you think that China is so far ahead of us in moving to this electric vehicle future?

MOTAVALLI: Well, first off, it is definitely true that EVs are a much smaller part of the market in the US than they are in China. But the market in the US is also growing dramatically. And I would predict 2024 will be the biggest EV sales year. Now China has basically a command-and-control type approach. And they can basically dictate that the country's carmakers will switch to EVs. Right now, it's a big debating point in the presidential election. And we are allowed to give a lot of pushback to any proposal, including switching to electric cars. But the world has basically already voted for that to happen, and it is going to happen very soon. So I think the change is inevitable, though it may take longer in the US than it does in China. I mean, there's other parts of the world that are even more adopting to EVs. In Norway, it's 90% of all new car sales, and you can't even buy from the Volkswagen Group anything but an EV. And that's a major sea change.

O'NEILL: Well, one of the things I've just seen is that BYD, a Chinese company, has just sort of lapped Tesla and become the biggest maker of EVs worldwide. And you wrote an article about BYD now building factories in Mexico?

MOTAVALLI: Exactly. Yeah. And these are the type of small cars, very bare bones vehicles, that Americans don't really like that much. But there's a lot of fear in the auto industry that they could start selling those EVs built in Mexico in the US, and they would avoid some of the biggest tariffs that are now in place against Chinese-made vehicles if they import them from Mexico. But BYD is saying that it's not going to do that. They say they've got their hands full just meeting orders in Mexico and in South America. If you go to Europe now you'll find a lot of Chinese-made cars on the market, in the US hardly any.

O'NEILL: So in your article, you mentioned that some Chinese cars in Mexico are as cheap as $21,000. And in China, the automaker BYD has started selling a car as cheap as $9700. Either way, that's a pretty drastic difference from a lot of cars here in the US. What's going on there?

In March 2024, BYD’s Seagull electric vehicle was being sold in China for as low as 69,800 yuan, or $9,700. (Photo: Quzhouliulian, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

MOTAVALLI: Well, right now you can't buy an EV in America for less than about $30,000. The average price of an EV I think is around $54,000. But keep in mind, gas car prices have gone up way high too—the average one of those is 45 to $50,000. Because people are buying big trucks with lots of options, and large cars are back in favor again. So the average price of any car in America is pretty high. I don't know if people realize it, but America has some of the strongest safety regulation for cars overall, with airbags, and early warning systems, and crash protection. China doesn't have those same regulations, it's not nearly as tough. And it makes it possible for them to build cheaper cars, which they can sell in markets like Mexico, which don't regulate cars as much as the US does either. I went to China, and I drove some Chinese EVs. This was like 10 years ago. And some of them were downright frightening. They would never pass American safety standards. But they were aimed only at the Chinese market. Now, when the Chinese have actually built cars intended for export to the US, like Volvo and Polestar both have done, they make pretty good cars.

O'NEILL: And a key aspect of buying electric in the US is that there are some pretty nice tax incentives, even with a high price point. But there's a number of requirements in order to get these tax credits. What's going on there?

MOTAVALLI: The Biden rules, to the Inflation Reduction Act, essentially had the effect of creating a lot of American manufacturing, because you don't get the incentives unless the car was built in America. And you'll get more incentives if the battery was built in America and the raw materials in the battery come from America. So that has led to the biggest boost in US manufacturing in, I don't know, 50 years—automakers and battery companies and recyclers announcing US-based plants. So it's really been a boost to the American economy.

O'NEILL: I'm thinking again about China and their significantly cheaper EVs. To what extent does something like that affect American carmaker ability to be competitive in a global marketplace?

MOTAVALLI: It affects it very much. But the US automakers are not competitive in the global marketplace. We hardly sell cars outside the US. There's some slight penetration in Europe now. I mean, you've got Stellantis is an international company. So it is selling Jeeps in Italy, for instance, and you could buy Chrysler minivans in Rome, or whatever. But you know, that's not a big part of the mix. And American companies have never had a huge export business, in general because they build cars that are not compatible with other markets. Like Ford, for instance. They have their own divisions in Europe that make cars for the European markets that are just more suited to those markets. So they're there, but they're not selling cars made in America that were intended for American audiences. American cars have just been too big, too gas guzzling, all those things.

US automakers including Ford and General Motors have forged partnerships with Tesla that will allow drivers of their vehicles to use Tesla’s charging network. (Photo: Mr. Satterly, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

O'NEILL: So as I understand it, on March 20, the EPA announced strict new emissions standards for cars and other vehicles. The rules are going to apply to models for 2027 and later, and they don't affect used vehicles. But even with those caveats, this is being described as, you know, a crucial climate action, one of the most important that the Biden administration has taken. What do you think the impact of these rules are going to be? And what kind of responses have you seen to them?

MOTAVALLI: It's nothing new. These rules have been in evolution for a number of years. It's essentially creating very strong incentives for people to buy EVs. But I've seen a sort of partisan uproar over it. Right now, in part because of a lot of rhetoric about EVs, both on the positive side from Democrats and on the negative side from Republicans, it's very split along party lines. A majority of Democrats say they would consider an EV for their next car. And a majority of Republicans say they would not consider one.

O'NEILL: Well, Jim, what do you make of this partisan split? What's going on there? Is it just increasing polarity in the US landscape generally, or--?

MOTAVALLI: Well, Americans are very sensitive about their car choices. It's like if you tell people they're going to take the guns away, people get very upset. If you tell people, you're not going to be able to buy your Ford F-150 pickup truck because the Democrats are going to take it away, that's a very effective organizing tool. The fact is, it's wrong. The Biden initiative is not a ban on gas cars. It is a evolution into electric and it's incentives for electric. And in any case, the Ford F-150 will be available as an EV. And it's going to be more capable than the one you already own. But you know, in terms of campaign rhetoric that might score with the public, you probably do fairly well with a message like that. And again, as I think it's akin to guns, telling people you're going to take their guns away.

An EV charging station for a car-share program in Los Angeles. Several US states, including California, will ban sales of new gas–powered cars starting in 2035. (Photo: Downtowngal, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

O'NEILL: Jim, what kind of misconceptions do you think Americans tend to have when it comes to EVs?

MOTAVALLI: Well, the biggest one is what they call range anxiety. And range anxiety is thinking you're going to run out of juice and get stranded somewhere. EVs have a lot more range than they used to. And it's typical that a new EV you buy should go 300 miles on a charge. It's not that different from the range of a gas car. So that's one. And they don't understand the public charging network that much. I don't think they realize that those networks are fairly robust now, and they're really across the country. So refueling your EV should be fairly easy. But the main things are range anxiety and price. EVs are still higher priced than gas cars. But I think that EVs are better cars than gas cars by almost any measure. And the people who are skeptical about them haven't driven them. You will immediately find that EVs are quieter, that they accelerate better, that they're going to need a whole lot less maintenance, and operating them also costs a whole lot less. So the purchase price is higher. But almost every other measure, they're better. They're also faster. If you look at the three fastest cars on the market today, which are under two seconds to 60 miles an hour, all three of them are electric.

O'NEILL: Well, so let's imagine a situation. I'm situated up here in Boston. Let's say I want to drive down to Philadelphia in an electric car. To what extent would I need to be worried about the distance?

MOTAVALLI: Well, depends on what kind of car you have. Like if you have a Tesla, you shouldn't worry at all, because there are Tesla charging stations everywhere. All the other automakers are switching to the Tesla standard, but that hasn't happened just yet. So if you have something other than a Tesla, you're going to be dependent on ChargePoint and Electrify America and other stations that are now dotting the landscape. Those charging stations have had a very hard time being 100% reliable. So people are showing up at charging stations and finding them out of order. And that's a big issue. It's one reason auto manufacturers are switching to the Tesla standard. Because the Tesla network has been much more reliable. Pretty soon you'll be able to charge your EV at Tesla stations, no matter what kind of brand it is. And so that should actually make things a whole lot better with charging.

Jim Motavalli is a freelance environmental journalist and blogger for Autoweek and Barrons (Photo: Seb Daly, Web Summit, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

O'NEILL: Well, Jim, so we had this all starting out in the context of China's massive EV market. But it sounds like you don't feel like the US is too far behind.

MOTAVALLI: I think we're gonna end up in the same place as China. It might take a little longer, but we're all heading in the same direction. If you look at the way the world is evolving, Europe as a whole, the European Union has actually enacted a ban on internal combustion cars as of 2035. Several American states have also done that, including New York and California. And this is the de facto rule in China. India has even talked about it. So the world is basically moving towards a situation where there will be no new gas cars sold by 2035. And if you look at what the automakers are saying, what their plans are, they're not planning to build any internal combustion cars after 2035. And many of them will stop selling them earlier than that. So this is not something that can be either stopped or started by the Biden administration. It's essentially where these global automakers have to be anyway.

O'NEILL: Jim Motavalli is a blogger with Barron's and Autoweek. Jim, thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

MOTAVALLI: Sure, great to be on.

Related links:

- Read Motavalli’s Autoweek article “Are Chinese EVs from Mexico a Threat to the US?”

- MIT Tech Review | “How Did China Come to Dominate the World of Electric Cars?”

- Learn more about the new EPA emissions rules

[MUSIC: Los Pinguos, “Cielo Escarlata” on Radio Latino, by Los Pinguos, Putumayo World Music]

DOERING: Just after the break, sewage sludge is dosing crops and livestock with toxic forever chemicals. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Along Came Betty, “Buying Clothes For My Imaginary Friend” on The Secret Parts of Fortune, by Biff Smith, published by Along Came Betty]

Sewage Sludge Danger

According to a study in the journal Environmental Health, over 40% of the six million dry metric tons of sewage sludge produced annually in the United States is later applied to the land. (Photo: City of Geneva, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

O’NEILL: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

If you’ve seen the movie Dark Waters, you may remember the story of [West] Virginia farmer Wilbur Tennant, whose cows mysteriously lost weight, developed tumors and died. His farm was just downstream from a landfill where Teflon manufacturer DuPont illegally dumped thousands of tons of toxic sludge containing PFOA chemicals, poisoning the cows that were drinking from the local stream. That real farmer was one of the first whistle blowers whose persistence in the 1990s lifted the veil on the dangers of PFOA and other PFAS known as “forever chemicals”. But we are now learning that the presence of PFAS on farms is a much more widespread problem. A 2022 study by the Environmental Working Group found that about 20 million acres of cropland in the US may be contaminated from PFAS-tainted sewage sludge spread on fields as fertilizer. In 2022, Maine became the first state to ban the practice of using treated sewage as fertilizer after officials discovered astronomical levels of PFAS in water, crops, cattle, soil and even farmers’ blood. Adam Nordell was owner of Songbird Farm, that had to be shut down.

Aerial photo of the Texas farms showing PFAS levels in soil and water. PFAS is toxic to human health in even tiny amounts. (Photo: Office of the Texas State Chemist)

NORDELL: Discovering PFAS on our farm was incredibly devastating. This directly undermined what we're trying to do on our farm. All farmers that I know work incredibly hard to steward the land, to perhaps pass the farm on to the next generation, and the last thing any farmer wants to see is their land and their water contaminated with forever chemicals. Farmers are also, we’re mission-driven. We're working hard for low pay. And you know, we all want to produce a safe product. We all are working to nourish our customers, to nourish our communities. And the last thing any farmer wants to do is to sell contaminated food.

DOERING: Now watchdog group, Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, or PEER, and five Texas farmers have filed a petition to take the Environmental Protection Agency to court for allegedly failing to protect the public from the risk of sewage sludge contaminated with PFAS. Joining me now to discuss is Kyla Bennett. She previously worked with the EPA for 10 years and is now PEER’s Director of Science Policy. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Kyla!

BENNETT: Thank you so much for having me.

Smoking piles of biosolids, and one of the Texas ponds that was tested. (Photo: Office of the Texas State Chemist)

DOERING: So how exactly does PFAS, these forever chemicals, end up in biosolid fertilizer used across the United States?

BENNETT: Well biosolids is actually just a euphemism for sewage sludge. So if you think about it, since PFAS is so ubiquitous in consumer products and food and water, anything that we flushed down the toilet or put into the sink and goes into a wastewater treatment system, that will end up going into the biosolids, because the wastewater treatment plants were not designed to remove PFAS. And indeed, they actually create more PFAS than they remove.

DOERING: How are they creating more?

BENNETT: So we don't really know for sure, except that PFAS chemistry is really kind of complex. And what happens is that whatever the treatment is, in the wastewater treatment plant, what it's doing is certain short-chain PFAS or certain compounds are recombining and forming more PFAS. So studies have been done that show the amount of PFAS in the influent going into the wastewater treatment plant is actually less than the PFAS coming out.

Pictured above is a wastewater treatment plant that treats domestic sewage. Part of this output could be used as biosolid fertilizer. (Photo: Montgomery County Planning, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

DOERING: Wow. So we're not just talking about a matter of concentration here as the sewage gets sort of decomposed at the plant, but it's actually creating more PFAS?

BENNETT: Correct. It's creating all sorts of different kinds, and more.

DOERING: So we're following the path of this PFAS as it goes from the wastewater treatment plant to, you know, spread on the fields, and then it actually can get into plants. How is that happening? How is it actually getting into these plants?

BENNETT: So when PFAS gets into water and soil, that's how plants get their nutrients in their water, they take it up through their roots, and that's the same way the PFAS is getting into the plants. So short-chain PFAS in particular, the ones that have six carbons or less, are readily taken up by plants. And they will just go mostly to the leaves and the stems. So some of the leafy vegetables like kale, rhubarb, things like that tend to have more PFAS than some of the, you know, things like tomatoes or onions, things like that.

One of the dead calves found on the Texas farms tested by PEER for PFAS contamination. (Photo: Office of the Texas State Chemist)

DOERING: So what do we know so far about the impact that agricultural products contaminated with PFAS can have on our health?

BENNETT: Oh, there are so many. In fact, just recently, a study came out that shows that people with high PFAS in their blood serum can be at much higher risk for cardiovascular disease. So certain PFAS are carcinogens, like PFOA and PFOS. EPA said in March of last year that those two PFAS, there's no safe level of them. They will cause kidney cancer, liver cancer, testicular cancer. They've been associated with all sorts of thyroid disease, diabetes, developmental issues in children, obesity and heart disease.

DOERING: These are some of the worst diseases you can get. I mean, you know, cardiovascular disease, cancers, this sounds pretty concerning.

BENNETT: It's very concerning, not just because of how PFAS actually can attack almost every organ in your body, but also how ubiquitous they are. Almost everybody tested, something like 98% of humans, have a certain amount of PFAS in their blood. So it's been found everywhere from the Arctic Circle, everywhere to even remote areas, because it travels through the air, through the water and through our soil.

Kyla Bennett is the Science Policy Director for PEER. (Photo: Courtesy of Kyla Bennett)

DOERING: So this class of chemicals we're talking about is often called "forever chemicals". What is it that makes PFAS so persistent in our environment?

BENNETT: One thing that all PFAS have in common is a backbone of fluorine and carbon atoms. And that carbon fluorine bond is one of the strongest bonds known in organic chemistry. It's almost impossible to break, and that's why they've achieved the nickname “forever chemicals”, because they just don't readily break down.

DOERING: So we're talking about PFAS in this sewage sludge fertilizer. Where in the US is this problem of PFAS in sludge being uncovered?

BENNETT: Right now the states that have the most problems, or at least that we're aware of, are Maine, Michigan, New Mexico and now Texas. But honestly, everywhere biosolids are spread we're going to have this problem, because I have never seen a sample of biosolids that have been tested to not have PFAS. They all have extremely high levels of PFAS, and biosolids are used on many, many conventional farms. They're not allowed to be used on organic farms. But any conventional farm can use biosolids, and those PFAS will get into the soil, the groundwater, the crops and the animals, which can give you PFAS in dairy, in meat and in vegetables and fruits.

DOERING: Now, Kyla, you mentioned Texas, and I understand that you're involved in analyzing samples from two Texas farms that were allegedly contaminated with PFAS and biosolids from a waste management company. What's happening there?

Among the produce grown at Songbird Farm were grains like wheat, rye, and oats, which the farm milled on-site. (Photo: Courtesy of Adam Nordell)

BENNETT: So it's really interesting. We were contacted by an investigator for Johnson County, Texas. She had some, what she calls victims, some farmers who were suffering greatly from not just the smells of biosolids being placed in the farm across the street from them, but they started noticing that their animals were dying, and they themselves were having health impacts. So together with Johnson County, Johnson County paid for a vast array of tests, that we tested soil, we tested surface water, we tested drinking water, and we tested some of the dead animals to find out how much PFAS was in these media, and we found that there were vast amounts of PFAS. One of the stillborn calves, for example—and because it was stillborn remember it never ate grass or drank water on that farm. It was, all the PFAS in this stillborn calf was from its mom through the placenta. We found 610,000 parts per trillion of just PFOS, which is one of the two PFAS that EPA says there's no safe level of. Well people eat calf liver all the time. So just staggering. And the two fish that we tested, one had 54,000 parts per trillion of PFOS, the other one had over 70,000 parts per trillion. So really high levels, dangerous levels. And so right now there are three parallel tracks of enforcement, if you will, going on. Johnson County has an ongoing criminal investigation into what happened. PEER, we did a notice of intent to sue EPA for their failure to regulate PFAS and biosolids. And then finally, there's a private law firm in Austin, Texas, which is suing Synagro, the company that produced the biosolids, for tort, to try to make these farmers whole again.

DOERING: Gosh. So how has this impacted the farmers there? I mean, are they able to even keep farming?

BENNETT: You know, because there's no law in the US about limits of PFAS in food, they could legally just continue to sell their fish and their meat. But because they are so concerned about their friends and neighbors who might be buying these products, they voluntarily stopped selling their products. And so their livelihood is gone. Literally overnight. They are no longer making money from their farm, and they still have these animals that are alive that they have to take care of.

DOERING: Tell me more about how those strategies might help hold companies that sell toxic sludge with PFAS to farmers accountable.

BENNETT: Well I think if the private lawsuit from Austin, Texas is successful, it will severely limit the ability of these companies to provide these PFAS-contaminated biosolids as fertilizer, because if these companies know that they could be held liable and have to pay for the damage that it causes, they're going to not want us to supply it anymore. So that's one possible pathway. And then our suit with EPA, hopefully it will spur EPA to actually start regulating PFAS in biosolids. So this provision of the Clean Water Act, Section 503, came into play in 1987. And EPA was mandated by the statute to every two years identify toxic pollutants in biosolids as step one, and step two, promulgate regulations if there's enough evidence that these toxic chemicals harm human health and the environment. Well, EPA has known for a very, very long time now, decades, that PFAS is harming human health and the environment. They've also known for a very long time that these biosolids contain PFAS. So their failure to identify these PFAS and promulgate regulations is a huge failure on their part to protect human health and the environment, which is EPA's sole mission.

SongBird farm also grew Abenaki Flint Corn (pictured above), a regional, heritage variety traced back to the western Abenaki people of what we now call Northern New England. (Photo: Courtesy of Adam Nordell)

DOERING: So in recent months, Kyla, we've seen EPA unveil some drinking water standards for PFAS. How might those standards help resolve this issue of PFAS ending up in the fertilizer that farmers are using?

BENNETT: It may not, unfortunately. I am all for those drinking water regulations, right now they're in draft form. EPA is very late in finalizing those. We're hoping they come out any day now. But all that's going to do is require public water systems to filter water down below a certain level of just six PFAS. And how that will impact the biosolids, probably not very much unless, what we all are hoping, is that if there are regulations limiting the amount of PFAS in water, one of the only ways to address that is to stop putting PFAS in the consumer product. So what EPA really needs to do is not just force public water systems to filter it out. But what they need to do is regulate PFAS as a broad class rather than this Whac-A-Mole approach of regulating one at a time, because we're talking about a class of 14,000 chemicals. So regulating six is a drop in the bucket, no pun intended there, but honestly, it's really not enough. So they need to regulate them as a class and ban all non-essential uses. And that's the only way that we will ultimately see biosolids be reduced or eliminated, the PFAS levels being reduced or eliminated in biosolids.

DOERING: Now, some folks like yourself say we should really stop producing this stuff, this is toxic, we need to, you know, cut it out entirely. So that's one option. But you know, even if we did that, the fact of the matter is that there is all this PFAS out in the environment, in our water supply, on farms. So what can be done to clean up these so-called forever chemicals once they're already out there?

BENNETT: Not a whole lot. With water, we can filter it, with drinking water, we can filter it, but then you have the problem of what you do with that PFAS-laden filter, which is now hazardous waste. There is some work being done up in Maine on how to clear PFAS out of cattle. And if—it turns out that if you give them clean water and clean food, they can remove it from their body more readily than humans can.

DOERING: They have a superpower?

BENNETT: They do, they have a superpower. So that's a possibility. But another way that people are trying to remediate some of these sites, they're putting in fast-growing plants that will uptake a lot of PFAS. So they're trying to draw it out of the soil and the groundwater using these plants, but then you have the problem of, okay, now you've got tons of this PFAS-laden plant material, what do you do with that? You can't landfill it because the PFAS will get into the leachate which then goes to a wastewater treatment system and we're back to where we started again, you can't incinerate it with a regular incinerator because PFAS can't be destroyed. You need really, really high temperatures to destroy PFAS and traditional incinerators don't really affect it that much. And it can become airborne and travel and then become deposited on the land and water again. So it really is a conundrum. And I often liken, I make the analogy between climate change and PFAS contamination. If we stopped burning fossil fuels tomorrow, we'd still have 425 parts per million of carbon dioxide in our atmosphere for decades, if not hundreds of years before it slowly starts coming down. That's not a reason not to do it, we have to do it. But it's gonna take a while to get back to where we should be. Same thing with PFAS, if we stopped emitting it tomorrow, the amount of PFAS in our water, our soil and our food is going to stay pretty leveled for decades, if not hundreds of years or longer before it starts coming down. Which is why it's important for EPA and the states to act now.

Adam Nordell and Johanna Davis owned and operated Songbird Farm together on a beautiful hilltop farm in Unity, Maine. They were among the 4 farms that were shut down due to dangerous PFAS contamination from biosolids. (Photo: Courtesy of Adam Nordell)

DOERING: This is such a huge issue, Kyla, you know, and it might feel daunting to some of our listeners hearing about just how widespread this problem is. So what can individuals do to limit PFAS in their daily lives?

BENNETT: You can do a lot. I have made a concerted effort in my life for the past five years to get PFAS out of my house. So you know, get rid of your carpets, don't have upholstered furniture that have PFAS in it. Don't buy makeup with PFAS. Don't buy anything in plastic containers, particularly number two plastics because those are the ones that are fluorinated. So I try really hard in my life to eliminate PFAS from our house, but I know that I'm privileged and not everybody has the ability to do that. For example, we have a organic farm that's a mile and a half from our house and we buy our produce from there. We know it's safe, because our town just put in a $10 million filtration plant. So the water is safe. It's an organic farm so there's no biosolids. So I'm pretty positive that the vegetables that I'm buying there are pretty low in PFAS if not PFAS free. And not everybody's able to do that. Unfortunately, it's hard to protect yourself, because you don't know which products contain PFAS. They're not listed as ingredients most of the time. So the only thing you can do is try to self-educate and contact companies and say, "Hey, do you use any fluorinated chemistry in this raincoat,” or in these hiking boots, or in these guitar strings, or whatever it is that you're buying. And it's time consuming. So there is a website that has PFAS-free products. And I often consult with that, that's how I got my rain gear. And so there are scattered lists around of brands that are PFAS free or lower in PFAS, and that's the only thing people can do until our government starts taking control and doing what they're supposed to do.

DOERING: Kyla Bennett is Director of Science Policy at PEER. Thank you so much, Kyla.

BENNETT: Thank you so much for having me.

DOERING: We’ll link to those resources Kyla Bennett mentioned for avoiding PFAS chemicals at the Living on Earth website, loe.org. And we reached out to EPA for a response but did not hear back in time for our broadcast.

Correction: An earlier version of this interview and transcript contained a numerical error regarding the number of Maine farms that had to be shut down.

Related links:

- PEER | “Remove Forever Chemicals from Biosolid Fertilizers”

- The New Lede | “Texas Farmers, Watchdog Group Demand EPA Act on PFAS in Farm Fertilizer”

- The Guardian | “Maine Plans Removal of PFAS From Sewage Sludge Used as Fertilizer”

- Learn more about Kyla Bennett

- WBUR | “Maine Nonprofit Buys PFAS-Contaminated Farm to Help ‘Forever Chemicals’ Research”

- Learn more about Song Bird Farm

- Learn more about PFAS free products

- Learn more Defend Our Health, where Adam Nordell now works on issues around PFAS farmland contamination

[MUSIC: ShadowFax, “Hey! Your Hat’s On Backwards” on Magic Theater, by ShadowFax, Excerpt from “Third Stone From the Sun” by Jimi Hendrix, Earth Beat! Records]

O’NEILL: Coming up, a powerful time machine that’s giving us clues about the early universe. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Keola Beamer, “E Ku’u Morning Dew” on Moeuhane Kika – Tales from the Dream Guitar, by Eddie Kamae/Myrna Kamae/Larry Kimura/arr.Keola Beamer, Dancing Cat Records]

BIRDNOTE®: The Birds of Yoga

Many yoga poses are named after birds, such as the mayūrāsana pose, named after the peacock. (Photo: © Mathias Appel)

O’NEILL: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

DOERING: For thousands of years humans have looked to the skies for spiritual inspiration, as BirdNote’s Trisha Mukherjee explains.

BirdNote®

The Birds of Yoga

[Calming yoga music]

Eagle pose. Crow pose. Peacock pose.

Each of these bird-inspired yoga poses has deep roots in Hindu mythology and philosophy.

[Changeable Hawk-Eagle call]

Eagle pose in Sanskrit is garudasana. Garuda is a giant mythical sun bird with a golden body and eagle’s beak. His wings have so much power that by flapping them, he can stop the spinning of heaven, earth, and hell.

[House Crow call]

Crow pose, or kakasana, harkens back to a legend in the Indian epic The Mahabharata. Many Hindus believe that crows bridge the worlds of the living and the dead. In an annual ritual called shraddha, people cook a feast for the crows outside to satisfy their ancestors who have passed on.

[Indian Peafowl call]

Peacock pose, or mayurasana, is a challenging arm balance pose. The peacock in Hinduism is a symbol of beauty, grace, and pride. Legend says that the peacock used to have dull feathers, but during a battle it shielded Indra, the god of the heavens. In return, he made the peacock’s feathers iridescent.

[Calming yoga music]

Next time you take a yoga class, breathe deeper, stretch longer, and rise higher by channeling the ancient energy of these fearless birds.

For BirdNote, I’m Trisha Mukherjee.

###

Written by Trisha Mukherjee

Senior Producer: John Kessler

Producer: Mark Bramhill

Managing Editor: Jazzi Johnson

Managing Producer: Conor Gearin

Content Director: Jonese Franklin

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Changeable Hawk-Eagle ML182224751 recorded by Rajiv Kalsi, House Crow ML514775631 recorded by Samim Akhter, and Indian Peafowl ML111560 recorded by Linda Macaulay.

Music: “Element Airborne” by Blue Dot Sessions.

BirdNote’s theme was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

© 2023 BirdNote October 2023

Narrator: Trisha Mukherjee

ID# yoga-01-2023-10-26 yoga-01

https://www.birdnote.org/listen/shows/birds-yoga

DOERING: For pictures, glide on over to the Living on Earth website, loe.org.

Related link:

Learn more on the BirdNote® Website

From the History Books

The 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster forced 47,000 people to evacuate their homes. (Photo: Tokyo Electric Power Co., TEPCO, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

O'NEILL: With me on the line now is Peter Dykstra, our Living on Earth contributor in Atlanta, Georgia. He's gonna give us a couple of stories about this week in history. Hi, Peter. What do you have for us from the history books?

DYKSTRA: Hi Aynsley. On March 26, going back to 1971, the Tokyo Electric Power Company, better known as TEPCO, opened the first of its six reactors at Fukushima Daiichi. And 40 years after that in 2011, what had grown into that six-reactor complex is swamped by a tsunami caused by a 9.0 magnitude earthquake. Fukushima then joined Chernobyl as a symbol of concern about the risks of nuclear power generation.

O'NEILL: And 53 years after that first reactor came online, it's still a big argument about whether the contaminated water from the 2011 near meltdown makes nuclear power an unacceptable environmental risk.

DYKSTRA: And 13 years after the near meltdown, there's still a debate whether nuclear power should play a role in rolling back greenhouse gases.

O'NEILL: And Peter, I believe your next history segment is from the previous year.

DYKSTRA: In April of 1970, the famous Canadian folk singer Joni Mitchell released her song Big Yellow Taxi, which decries abuse of the environment with lines like "They paved paradise and put up a parking lot," and you can thank me for not singing it.

O'NEILL: I think that Big Yellow Taxi can really be agreed upon as probably the greatest song of the environmental movement.

DYKSTRA: Well, other than Big Yellow Taxi, do you have another favorite?

O'NEILL: Oh, one that I like is "Feels Like Summer" by the artist Childish Gambino. But Peter, I don't mean to always play the generation card on you, but I do want to know, do you happen to have a favorite from this century?

DYKSTRA: Ouch, playing the generation card. But here you go with a 21st century favorite. Let's try "SOS (Mother Nature)" by Will.i.am.

O'NEILL: All right. Well, we'll have to tune in. Thanks for bringing us these stories and these songs, Peter. Peter Dykstra is a Living on Earth contributor, and we'll talk to you again soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, talk to you soon, young person. Thanks very much.

O’NEILL: And there’s more on these stories on our website, loe,org. And here’s Joni Mitchell.

Related links:

- Read more about the Fukushima nuclear disaster

- Listen to more Joni Mitchell music

[MUSIC: Joni Mitchell, “Big Yellow Taxi” on Ladies of the Canyon, Warner Records Inc.]

Black Hole Breakthrough

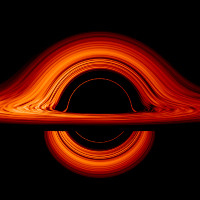

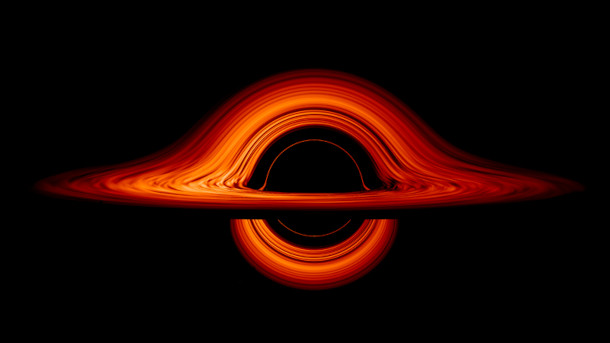

Image depicting an accretion disc around a black hole. Although light cannot escape a black hole, scientists are able to observe the bright, hot gas swirling around it. (Photo: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center/Jeremy Schnittman, cmglee, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

DOERING: At the heart of many large galaxies are enormous black holes, objects so mysterious that cosmologists are largely in the dark about them. Black holes are regions of space so dense that even light can’t escape their powerful gravity, making them extremely difficult to observe. Now the James Webb Space Telescope, in operation since 2022, is giving us clues that could help reveal the secrets of black holes. Using its data, an international team of astronomers recently reported the discovery of the oldest black hole ever observed, dating to more than 13 billion years ago. That’s only 400 million years after the Big Bang, a blink of an eye on astronomical timescales. The findings of the study, published in the journal Nature, suggest that early black holes may have formed differently and grown much more quickly than previously thought. Here to discuss is the lead author of the study, Dr. Roberto Maiolino, Professor of Experimental Astrophysics at the University of Cambridge. Welcome to Living on Earth!

MAIOLINO: Hello, thank you for inviting me.

DOERING: So take us to class for a brief moment. What exactly is a black hole?

MAIOLINO: So a black hole is a region of space where the pull of gravity is so strong that not even light can escape. And typically, we group black holes in two main classes, black holes resulting from the collapse of massive stars—these are called stellar black holes—and so-called supermassive black holes, which can have masses of a million to billions of times the mass of the Sun, which are located in the center of most galaxies, and how they have formed is debated. Certain they have been accreting gas from the host galaxy, but their origin is still a matter of debate.

DOERING: So how big is this black hole that you've discovered? And what does this tell us about black holes and the universe that we didn't know before?

An artist’s depiction of the Milky Way galaxy. The distant black hole discovered by Maiolino and others is about the same size as the one at the center of the Milky Way, but the fact that it achieved such large mass so soon after the Big Bang suggests that black holes may be able to grow more quickly than previously thought possible. (Photo: Pablo Carlos Budassi, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

MAIOLINO: Well, is not particularly big, in the sense that it's of the order of a few million times the mass of the Sun. The black hole at the center of our Milky Way is similar, is about 4 million times the mass of the Sun. However, what makes this black hole particularly exciting is that it has reached such high mass very early in the Universe. We are observing it at an epoch when the Universe was only about 400 million years old, about 13.3 billion years ago. So actually, very soon after the Big Bang. The standard scenarios that were accepted until recently about the formation of these early massive black holes was that they would form out of the relatively light black hole seed, formed out of the remnants of massive stars, and then accrete and grow by eating gas from the host galaxy. But there is a limit at which these black holes could grow according to theory. And with this scenario, essentially, is nearly impossible to make such massive black holes so early in the Universe.

DOERING: So how do you explain this discrepancy?

MAIOLINO: Is not simple. Astronomers had to come up with alternative theories. One possibility is that black holes were born big. There is indeed a theory that in the early Universe, primordial clouds of pristine gas made of helium and hydrogen, under certain conditions would collapse to form an already very massive black hole. If black holes were born so big, then it takes not that much effort, let's say, to grow to the size that we see in this system. Alternatively, black holes could actually originate from stellar remnants—so the collapse of the first generation of stars—but then may have grown much more quickly, either by merging with other black holes, or by gobbling matter much more rapidly than we thought it was possible. So currently, we can't distinguish clearly between these two scenarios. However, this black hole is seen to actually being quite greedy. It's accreting matter indeed at a very high rate. And therefore, it makes us think that the scenario in which this has grown by accreting a lot of matter very quickly could actually be a real possibility.

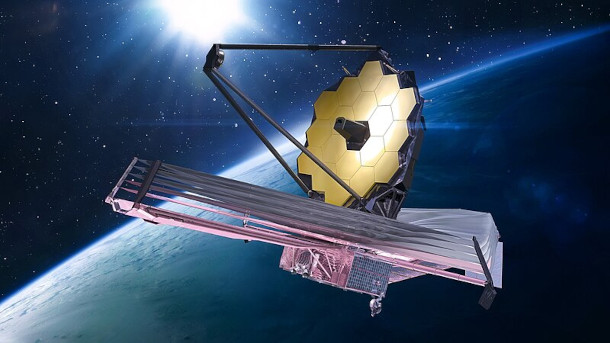

An artist’s rendering of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) above the Earth. The large mirrors on the telescope help it to collect light even from the distant reaches of the Universe. (Photo: NASA/dima_zel, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

DOERING: So black holes are called that because, well, they're black. Light can't escape from them. So how can we actually see or identify one?

MAIOLINO: Yeah, indeed, we don't see directly the black hole. By definition, the black hole doesn't emit light. But what we see is the glow of the gas swirling around the black hole, which becomes indeed very hot, and can radiate a lot in the ultraviolet. We also see the gas which is being illuminated by such energetic radiation. And typically, this results in very dense gas, which is seen around these supermassive black holes, and also very highly ionized gas, that is gas in which the atoms have been stripped of many of their electrons. And so this is a typical signature of gas surrounding a black hole.

DOERING: Now, I understand that you were able to discover this black hole using data collected by the James Webb Space Telescope, which was launched in December 2021. And I don't think it's a stretch to call JWST one of the great achievements of our time. How did the telescope make this discovery possible?

MAIOLINO: These galaxies was already peculiar because it has an exceptionally high luminosity. So there was already the suspicion that the light that we see from these galaxies would not be coming simply by stars, but there might be something more, such as accretion onto a supermassive black hole. The main problem, actually, is that despite being intrinsically luminous, being so far away it becomes very weak, because it has to travel so much throughout the universe. And that's where the James Webb Space Telescope essentially made this possible. Because it's being the largest telescope in space, with its very large mirror, it can actually collect enough light, even from the most distant part of the Universe, to make the light and the signature of these processes detectable with its instrumentation. It has several fantastic features. But what makes Webb really unique is its sensitivity. It observe primarily in the infrared. And in this band, its sensitivity is orders of magnitude better than any previous facility. Just to give you an idea of the magnitude of the leap, it is equivalent in the visible as suddenly upgrading Galileo's telescope to the modern large telescopes, compressing 400 years of discoveries in the 10, 20 years of operation of James Webb. So we are really making a gigantic leap in the discovery space and in our understanding of the universe.

Roberto Maiolino is professor of Experimental Astrophysics at the Cavendish Laboratory (Department of Physics) and at the Kavli Institute for Cosmology of the University of Cambridge. (Photo: Courtesy of Roberto Maiolino)

DOERING: So what's been the most surprising part of telling this story to all these journalists you've been talking with?

MAIOLINO: Well, the most fascinating thing, I think, not only to journalists, but to myself as well, I would say, is the fantastic new golden period that we are living in astronomy thanks to Webb. My career is 20, 30 years long. And I have never experienced such an excitement, because really, Webb is completely revolutionizing several areas of astrophysics. You know, before Webb, my colleagues were saying, maybe the Universe is not so exciting, is just a extension of what we know, but actually, what we're seeing with Webb in this new domain is actually mostly unexpected and completely new. So it's a totally new endeavor, and totally new excitement in making these new discoveries and new findings. And many of these, we still are struggling to understand. And that's also the fascinating part, because if we understood everything, that would be quite disappointing. Instead, Webb is explaining many things, but also is opening extremely interesting new questions that we want to answer and tackle in the coming years with more observations.

DOERING: Before you go, you know, it's obvious that this is scientifically fascinating. But why is it important for humanity to be able to learn more about the universe that we live in?

MAIOLINO: That's a big question. I think is part of the human spirit to understand more of the universe in which we live, and the nature of the everything. I mean, of course, the discovery of Galileo the sun was not orbiting around the Earth but other way around, of course, didn't change the life of the individuals on Earth, but was in the end mind blowing, because it changed the perspective of humanity, of where we are and what we are and our place in the universe.

DOERING: Roberto Maiolino is a professor of experimental astrophysics at the University of Cambridge. Thank you so much.

MAIOLINO: Thank you so much. Bye bye.

Related links:

- Read the University of Cambridge announcement of the discovery

- Access the study in Nature

- View a gallery of images from the James Webb Space Telescope

[SFX – Phantom Galaxy: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2dgle5maku8&t=8s]

Star Sounds

Composite images and data from a series of infrared, optical, and X-ray instruments make up this view of Messier 74, a spiral galaxy also known as the “Phantom Galaxy”. (Photo: NASA, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

O’NEILL: We leave you this week with sounds from deep space.

[SFX – Phantom Galaxy: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2dgle5maku8&t=8s]

O’NEILL: That’s the “Phantom Galaxy”, M74, which is a gorgeous spiral galaxy, just like our own Milky Way, that’s 32 million light-years away from Earth. What you’re hearing is infrared and optical data from the James Webb and Hubble Space Telescopes, plus x-rays from the Chandra observatory. NASA turned these signals into sound in a process called “sonification”, which creates an experience you don’t need to be a scientist to enjoy. So, what sounds like just the plucking of a harp actually represents stars and clusters.

[SFX – Jellyfish Nebula: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NqBfQeJqkfU ]

O’NEILL: Much closer to home at just 5000 light-years away is the Jellyfish Nebula, the remnant of an exploded star, or supernova. The Jellyfish Nebula appears right next to the foot of Castor in the Gemini constellation, but you’ll need a powerful telescope to see it. This sonification also draws on x-ray data from Chandra, as well as radio data from the Very Large Array. The water-drop sounds represent background stars.

[SFX – Jellyfish Nebula: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NqBfQeJqkfU ]

O’NEILL: You can find out more and see stunning images of the Phantom Galaxy and Jellyfish Nebula on the Living on Earth website, loe.org.

Related links:

- More NASA Sonifications

- Sonification of Phantom Galaxy

- Sonification of Jellyfish Nebula

[MUSIC: Junior Mance, “A Smooth One” on Junior, The Verve Music Group]

O’NEILL: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Josh Croom, Karen Elterman, Swayam Gagneja, Sommer Heyman, Mattie Hibbs, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Sarah Mahaney, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Allison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at loe.org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments@loe.org. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth