April 26, 2024

Air Date: April 26, 2024

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Uncle Sam Wants YOU for Climate Corps

View the page for this story

On Earth Day President Biden announced the official launch of his new climate-focused jobs program, the American Climate Corps. Maggie Thomas is Special Assistant to the President on Climate and joins Host Aynsley O’Neill to discuss the thousands of jobs the Corps offers in community outreach, biological surveys, invasive species removal and more. (12:36)

Pushback Against 'Chemical Recycling'

/ Kristina MarusicView the page for this story

Small towns in Appalachia are being targeted for so-called chemical recycling plants, but residents are pushing back and citing concerns about chemical fires, air pollution, and toxic wastewater polluting local rivers. Opponents in Point Township, Pennsylvania succeeded in canceling a project there, and Kristina Marusic of Environmental Health News joins Host Jenni Doering to discuss two other proposed chemical recycling plants in Ohio and West Virginia. (11:07)

Lake Erie Sickly Green

View the page for this story

Lake Erie is being sickened by agricultural runoff and polluted wastewater, turning this important source of freshwater green. The US Department of Justice and two environmental groups recently filed suit against the Campbell Soup Company for its alleged contribution to the problems. Lake Erie Waterkeeper Sandy Bihn joins Host Aynsley O’Neill to explain the toll that multiple sources of pollution are taking on the lake. (09:01)

Lithium from Deep Underground

/ Wyatt MyskowView the page for this story

Lithium is used in electric vehicle batteries and plays a key role in the global shift towards clean transportation, but current extraction methods come with environmental costs. Some companies are exploring an alternative that taps brine water deep in the Earth. Wyatt Myskow of Inside Climate News joins Host Jenni Doering to explain how it works and what questions about its impacts remain. (10:15)

The "Green Flash"

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

On rare occasions a green “flash” can appear on the horizon at sunrise or sunset. Living on Earth’s Explorer-in-Residence Mark Seth Lender has been lucky enough to catch it more than once. (02:43)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

240426 Transcript

HOSTS: Jenni Doering, Aynsley O’Neill

GUESTS: Sandy Bihn, Kristina Marusic, Wyatt Myskow, Maggie Thomas

REPORTERS: Mark Seth Lender

[THEME]

DOERING: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

DOERING: I’m Jenni Doering

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill

The American Climate Corps is now hiring.

THOMAS: All positions that are listed on the website, all have some kind of climate or environmental impact. That means clean energy, it means climate resilience, which is a new burgeoning workforce that we really need to develop today. And we want to make sure that we're equipping this next generation with the tools to succeed in the workforce of the future.

DOERING: Also, getting lithium from deep inside the Earth.

MYSKOW: A really big factor that makes it an exciting option is that it can exist with other infrastructure. Those facilities bring that water up to do the geothermal process. What they're proposing is okay, we're already bringing it up, why not extract the lithium from this water, and get both the geothermal energy from it and also lithium.

DOERING: That and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Uncle Sam Wants YOU for Climate Corps

The American Climate Corps will partner with existing programs like AmeriCorps. (Photo: EL Gringo, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

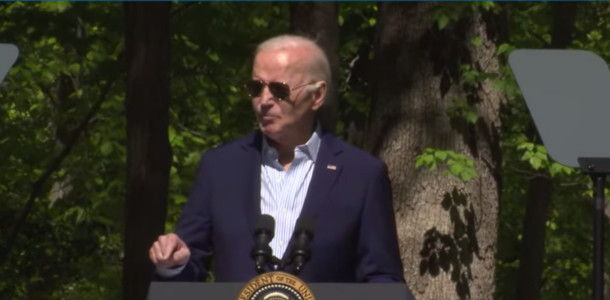

At an Earth Day event in Virginia just outside Washington, DC, President Biden announced the official start of his new climate-focused jobs program.

PRESIDENT BIDEN: It's patterned after the Civilian Conservation Corps and the Peace Corps and America Corps. Like them, it brings out the best in young people to do what's best for America. And we will put tens of thousands of young people to work at the forefront of our climate resilience and energy future, clean energy future. Today, I'm proud to announce that Americans across the country can now apply, now apply to become the first members of the American Climate Corps.

[APPLAUSE]

O’NEILL: All kinds of skills and industries are needed to address the climate crisis, so the jobs board for the Corps lists everything from community outreach to biological surveys to invasive species removal. Maggie Thomas is Special Assistant to the President on Climate and is here to explain just what the American Climate Corps has to offer. Maggie, welcome to Living on Earth!

THOMAS: Thanks so much for having me, really excited to be here.

O'NEILL: So exciting news, the website is now live for the American Climate Corps. Walk me through the history of this program. How did we get to this point?

THOMAS: Yeah, it's a really great question. And I think one of the most exciting parts about President Biden's American Climate Corps is really that it harkens back to as early as the 1930s, when President Roosevelt originally launched the Civilian Conservation Corps or the CCC. FDR launched this program to put millions of young men to work. And really with the idea that our economic crisis at the time, and the environmental crisis and the crisis of the Dust Bowl, were intertwined, they were one and the same. And so through a public works program, and that the CCC ultimately became really one of the New Deal's most popular programs, FDR put hundreds of thousands of young men to work. And even though today we have new crises, and we have a whole new diverse generation of young people who can be put to work, we thought to ourselves, it's a really good idea. Let's see if we can do it again. And so that's what President Biden's American Climate Corps is all about. It's this idea that in every community across the country, everybody has a role to play, we need to field a full team to tackle the climate crisis. And we want to make sure that at the federal level, we're providing jobs in communities across the country. So right now you can go on to climatecorps.gov, you can apply, we have about 2,000 positions that are listed with lots and lots more on the way. And it's really exciting.

President Biden delivers a speech commemorating Earth Day on April 22, 2024. (Photo: The White House, YouTube)

O'NEILL: Alright, so looking at the website, I think there are some programs that are sounding pretty familiar to some of our listeners, AmeriCorps for one. What kind of jobs are going to be open through that?

THOMAS: Yeah, so the way the American Climate Corps works is that we're going to leverage a number of implementing partners, which means that we're working with federal agencies, we're actually working across seven federal agencies to launch this historic initiative. We're working with local nonprofits, grantees of those federal programs, and state-based Climate Corps as well. So there have now been 13 states that have come forward and launched state-based Climate Corps programs that are at varying stages of implementation. And we want to make sure to leverage every single one of those programs. We know there's incredible work that's going on across the country right now. And it is our job to lift that up and expand those opportunities. So AmeriCorps is a key partner in the American Climate Corps, they are actually the lead agency, we are establishing an ACC hub at AmeriCorps. And, you know, there are a lot of benefits that come from being in an AmeriCorps position as well, one of which is a Seagull Education Award, which means that if you complete your term of service, you can get a little over $7,000 of student debt relief that can be used for student debt, like I mentioned, or for future education. So there are certainly a lot of benefits that come from AmericaCorps-specific positions. The other thing that you'll notice is that all positions that are listed on the website, no matter what implementing partner that they're being hosted in, all have some kind of climate or environmental impact. That means climate, it means clean energy, it means climate resilience, which is a new burgeoning workforce that we really need to develop today. And we want to make sure that we're equipping this next generation with the tools to succeed in the workforce of the future. And so that's really what the positions that you see on the website are all about.

The American Climate Corps is in part inspired by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Civilian Conservation Corps, which put hundreds of thousands of young men to work in the 1930s. (Photo: Richard, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

O'NEILL: And another program that I'm seeing is the Forest Corps. What's that one about?

THOMAS: Yeah, the Forest Corps is a new partnership that we announced last fall between AmeriCorps and the US Forest Service. One of the really, really tragic impact of the climate crisis is the large-scale wildfires that we're seeing across this country. We're seeing wildfires burn hotter, faster, and they are more devastating than ever before. And so one of the thoughts that we had was how do we make sure to give young people the tools that they need to succeed in case they want to become wildland firefighters? We know we're going to need a whole lot more wildland firefighters than we have today to tackle the impacts of the climate crisis. And we wanted to make sure that through those training opportunities, we were actually giving young people an opportunity to make an impact today during their term of service. And so you know, you can imagine as part of Forest Corps, you will have young people all across the country, say, clearing defensible space around communities that are in the wildland urban interface, where you have hazardous fuels right next to home. So we want to make sure to be protecting those homes, doing the same, you know, clearing brush and forests that are at high risk of wildfire and doing that in line with the Forest Service's wildland fire crisis strategy, to make sure that when the forest says, you know, we've got priority areas, that we're putting young people to work in those priority areas to get the job done.

O'NEILL: And there's also jobs related to FEMA, there's gonna be the FEMA Corps. What will that look like?

THOMAS: Yeah, absolutely right. I think disaster response and preparedness are two absolutely critical careers that we can imagine needing to expand a whole lot more in a future warmed world. So one of the things that we need to do is to be able to prepare for those disasters, to make sure that communities know when disaster strikes, what do you do? Where do you go? What are the resources that are available, so that the community is most prepared as possible. And once disaster does strike, which hopefully it doesn't, that we are sending people in as quickly as possible to repair and rebuild. And to do that in a way that is cleaner, that is better, that is stronger than ever before.

The Forest Corps will collaborate with the US Forest Service and AmeriCorps to train workers in wildfire mitigation. (Photo: Pacific Southwest Forest Service, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

O'NEILL: Now, the Biden Harris administration has this Justice40 goal, which as I understand it, is where 40% of the benefits of government investment in things like clean energy or sustainable housing must be directed towards disadvantaged communities. How is that reflected in the American Climate Corps?

THOMAS: Yeah, we want to make sure that the American Climate Corps looks like America, first and foremost. We know that we've got a new diverse generation of young people that want to be put to work in careers in climate, clean energy, and climate resilience. And we want to make sure that we're giving them the opportunity to do that, and the tools to succeed in the workforce of the future. And so one of the ways that we do that is we just make a commitment. And we say, look, we know that the American Climate Corps needs to serve all of communities around the country. And it needs to look like all of those communities. And that's a really, really important goal for us, as the President has been building this program. We also know that there are some communities that are indeed hit first and worst. And so we want to make sure that we're prioritizing those communities when we're selecting projects and locations for those folks to go to work in.

O'NEILL: And so if you're listening to this story, and you're going, sounds pretty neat, I'm in, how does one join the American Climate Corps?

THOMAS: It's simple, all you have to do is go to climatecorps.gov, look for a position that is exciting to you and apply directly through the site. The first class of the American Climate Corps will be deployed in June of this year. And the website will be live and rolling and taking applications for all of the positions that we're recruiting for over the course of the next several weeks and months.

Other American Climate Corps jobs will focus on disaster response and preparedness. (Photo: Nicholas Erwin, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND)

O'NEILL: I know there's going to be so many jobs, so this really is probably not a one answer fits all, but how permanent are these positions going to be?

THOMAS: Yeah, so all the positions in the American Climate Corps are term limited, which means they are likely going to be, you know, you could imagine a summer term position, perhaps up to a year. Some of the positions themselves, you know, may get extended, and that's sort of up to the American Climate Corps member and their project host, of course, but the idea is that these really are term limited positions, to fill a clear and present gap and need in climate impact that we know needs to happen in communities across the country, and make sure that young people have the skills in order to succeed in the workforce of the future. And so these are not permanent jobs, but they are giving young people an opportunity to be put on a pathway to a permanent job.

O'NEILL: Now, this was not the only part of the President's announcement. What else happened on Earth Day?

THOMAS: One in particular, we're really excited about, which is a new partnership with the North American Building Trades Unions nonprofit partner called Trades Futures, and NABTU and Trades Futures and the American Climate Corps got together because we really wanted to put our heads together around how do we ensure that American Climate Corps positions really do lead to good paying union jobs? What are the skills that we need to make sure that we're equipping young people with in order to put them on a pathway into registered apprenticeships, if that's the way they want to go, or perhaps a career in the federal government. And so this new partnership announcement that the President made on Monday is going to make the NABTU preapprenticeship curriculum, which is really the industry leading curriculum on training and workforce development, available to every American Climate Corps member during their term of service. And that's really exciting, because it means we're making good on the promise that we made, ensuring that these jobs really do lead to good paying union jobs. The other announcement that the President made on Monday that I think is really exciting, is that a majority of the American Climate Corps members are actually going to have an expedited pathway into federal service, again, if that's the route that they choose to go. We really saw the American Climate Corps as an opportunity to expand pathways. And that's what these two announcements are all about, pathways into good paying union jobs, if that's the trajectory that these young people want to go on. Or if you want to go directly into the federal service, there's now an opportunity and an expedited pathway to do that, if you're a member of the American Climate Corps. And the goal is to make joining the American Climate Corps as attractive as possible. We know that there is an infinite number of climate solutions and work to do out there in communities across the country. And so we want to make sure that we're equipping young people with the tools to do just that.

Maggie Thomas is the Special Assistant to the President for Climate and Senior Advisor for Strategic Planning, White House Climate Policy Office. (Photo: Courtesy of Maggie Thomas)

O'NEILL: So I mean, this is sounding really exciting. It's all sounding really promising. The thing is, we are, in fact, in an election year, and the curiosity is, how does this program stick around after the election? If the administration changes, what's going to happen to this program?

THOMAS: It's a great question. And we're working really hard to make sure that this program lasts for years to come. And we're building those decisions into the implementation and the design of the program. So, you know, one of the things that always comes to mind for me is, it's hard to say no to successful programs like this. And we want to make sure that we are really reaching every community across the country and having an impact in each one of those communities. And I think the impact of this program will become immediately clear to folks when they see young people put to work gaining the skills that they need to be members of the workforce of the future, and making a really clear, tangible climate impact in communities across the country. And, you know, from our perspective, we're doing everything we can to sprint at that goal. The President has set big bold goals before, he will continue to set big bold goals when it comes to his climate agenda. And the American Climate Corps is no different.

O'NEILL: Maggie Thomas is the Special Assistant to the President for Climate in the White House. Thanks for joining us, Maggie.

THOMAS: Thanks so much for having me. It was a great conversation, and I hope everybody goes out and applies to join the American Climate Corps.

Related links:

- The American Climate Corps website

- Grist “The American Climate Corps is Now Hiring”

- The White House “FACT SHEET: President Biden Marks Earth Day 2024 with Historic Climate Action”

- Watch several speeches commemorating Earth Day including President Biden

[MUSIC: Supertramp, “Take the Long Way Home” on Breakfast in America, by Roger Hodgson, A&M Records]

DOERING: Just after the break, a small Pennsylvania town tells a proposed chemical recycling plant, “Back off!” Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Biff Smith, “Five of a Kind” on Biff Smith Solo Piano, by Biff Smith, self-published]

Pushback Against 'Chemical Recycling'

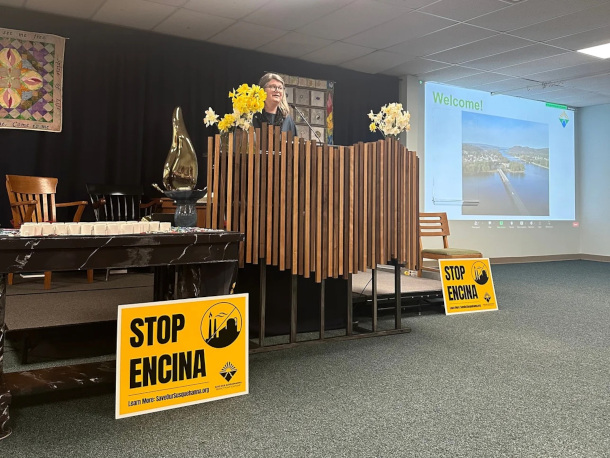

Save Our Susquehanna members tabling and giving out signs at a river event at the Campus Theatre in Lewisburg, PA. (Photo: Courtesy of Sandy Field)

O’NEILL: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

Texas-based Encina corporation recently canceled its plans to develop a chemical recycling plant for plastic waste along the banks of the Susquehanna River in Point Township, Pennsylvania. So-called chemical recycling is an umbrella term for different techniques that use heat, pyrolysis, and/or chemicals to break plastic waste down into fuel or component chemicals like benzene, toluene, and xylene that can be used to create new plastic products. It differs from mechanical recycling, which physically breaks plastic down before repurposing it. The facility in Pennsylvania was proposed to use millions of gallons of water a day from the Susquehanna River, threatening to pollute a vital source of drinking water with microplastics and “forever chemicals”. Sandy Field is a member of the local advocacy group Save Our Susquehanna.

FIELD: We know that microplastic and forever chemicals, you know, PFAS chemicals are not actually regulated in wastewater in Pennsylvania. And so those would have been found in the effluent, 2.9 million gallons a day from the river, used to wash the plastic and then put the water back in the river after some treatment. There would have been carbon dioxide emissions and other emissions from burning fossil fuels. And then they were going to make chemicals. And so the site is actually in the 100-year floodplain. So we were concerned about the storage of chemicals and the manufacturing of chemicals at that site, the possibility of leaks into the river, the possibility of flooding, but also they were going to ship the chemicals by rail along the river. And so we were concerned about spills and derailments and things like that happening during that process.

DOERING: The company Encina decided to back down after intense pressure from Save Our Susquehanna led a local council to pass a resolution that “strenuously and unequivocally” opposed the plant. Encina says that even though it will not proceed with construction in Point Township, it plans to “pursue other opportunities in the United States and around the globe to increase recycling and lessen society’s reliance on petroleum.” Sandy Field and her fellow activists say they’ll try to thwart those plans, too.

Sandy Field kayaking on the Susquehanna River downstream of the proposed chemical recycling site. (Photo: Courtesy of Sandy Field)

FIELD: We've learned so much about the plastics crisis, and about advanced recycling, that everyone wants to stop it, that it's just a bad idea. And we don't want it to go anywhere else.

DOERING: Late in 2023, the advocacy groups Beyond Plastics and the International Pollutants Elimination Network performed case studies of the 11 chemical recycling plants that were then operating in the U.S., one of which has since shut down. They concluded that chemical recycling mainly produces hazardous waste and greenhouse gasses, with only a small fraction of the plastic actually being reused. Kristina Marusic of Environmental Health News has been reporting on Point Township and two other proposed plants in the Appalachian region. Kristina, welcome back to Living on Earth!

MARUSIC: Hi, Jenni, thanks for having me.

DOERING: So what are local communities saying about these so-called chemical recycling plants? And why are they pushing back?

Sandy Field speaking at a public meeting at the Unitarian church in Northumberland, PA, near the proposed chemical recycling site. (Photo: Courtesy of Sandy Field)

MARUSIC: Each of these communities is relatively small. The proposal in West Virginia comes from a company called Empire Diversified Energy. And that company initially proposed a medical waste processing facility at this site. But there was a lot of community resistance to that. The community heard that they were going to be incinerating medical waste and really quickly said, "absolutely not, we don't want that in our neighborhood". So after there was lots of vocal community resistance to that plan, the company changed their plan, and announced that they would instead build a chemical recycling facility at the same site that would convert plastic waste into energy for electricity, and chemicals that could be used for fuel and other products. The folks who live in Follansbee, West Virginia, that's also a very small community population, around 2,700 people, and people there are concerned about air pollution, they have several other sources of air pollution in the region, and the region is a valley. So they're worried about pollutants being trapped, because of the way that air moves geographically through the region, and kind of increasing their overall burden of air pollution. And then they're also worried about the potential for explosions and accidents. These types of facilities are typically using heat, like really high temperature heat or really volatile chemicals or both for these processes. And so the ones that are functional, we've seen some pretty scary stories about big explosions, big fires, big accidents, particularly one in Ashley, Indiana, a Brightmark facility has been in the news a lot in the last couple of years for some really big kind of scary chemical fires. And so the people in Follansbee, West Virginia, where this proposed site is, read those stories and said, "Wait, we only have a volunteer fire department here, you know, we're a really small community, what happens if there's like a huge chemical fire at a plant like this?"

DOERING: Yeah, I mean, we've seen what happened in East Palestine, Ohio, when an industrial fire happens and can release massive amounts of pollution into a community.

MARUSIC: That's right. The activists I spoke with in Follansbee mentioned that too. They said, "These are the same chemicals that caused the fire in East Palestine, and we saw what happens when small community that doesn't have like a huge emergency response team available faces an incident like this, and we're worried about something like that happening here."

Akim Lattermore in front of her Youngstown, Ohio home. Lattermore and other residents fought to stop SOBE’s proposed chemical recycling plant. (Credit: Kristina Marusic for EHN)

DOERING: Let's talk about Youngstown, Ohio. How does that community feel about the so-called chemical recycling plant that's being proposed there?

MARUSIC: The proposal in Youngstown, Ohio comes from a company called Sobe Thermal Energy Systems. And they're proposing to convert not only plastic waste, but also tires and electronic waste into fuel. So essentially just incinerating all that stuff or heating it in a oxygen-free environment. There's a lot of contention about whether it's appropriate to use the word incineration. Because the industry is often saying like, you know, we're doing this in a safer way, we're heating it in a different way that's not less burning and more melting. But you know, the end result is kind of the same, that these products are melted down and broken up into component parts that can then be used for something else. But in each instance, there are some toxic air emissions and there's generally a pretty significant volume of hazardous waste created through this process as well. So that community is also concerned about air emissions and the potential for accidents, especially because the proposed site is in a really busy urban area. And there are a lot of concerns in that community about environmental justice, because a lot of residents in the region are people of color, are low income, and are people who don't speak English as their first language. So they may not have access to like public meetings with information about the proposal on the site and what it might mean for the health of the community.

The Shell ethane cracker plant in Beaver County, Pennsylvania turns ethane, a component of natural gas, into tiny plastic pellets. These are then used to make plastic products, a process that emits multiple environmental pollutants including greenhouse gases. (Photo: Ted Auch, FracTracker, Flickr, CC BY NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: So what tools do these communities have at their disposal to try and prevent some of these plants from moving in?

MARUSIC: Some of these communities have been focusing on zoning. So a lot of these facilities are proposed in kind of rural or residential areas, and one thing that local government can do is, you know, look at their zoning rules and potentially make changes to their zoning rules. Youngstown, Ohio came up with an interesting solution to this. City council there, after being approached by activists in the community who were opposed to this chemical recycling plant, passed a one-year moratorium on this type of facility, so that they could take more time to do their research and hear from the company and determine whether this was something that was safe for the kind of urban area where they want to put this facility in. So they passed that in December and the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency actually did issue a permit to the company that wants to build this advanced recycling facility. But because city council passed this one-year moratorium on these types of projects, the project can't move forward at this time. And they did that in December of 2023, so they now have until December of 2024 to decide whether the moratorium will become a permanent ban, or whether they will lift it so the company can move forward with its plans.

DOERING: So this is all taking place in the Appalachian region. Why is this a sought-after location for chemical recycling plants?

Kristina Marusic covers environmental health and justice issues in Pittsburgh and Western Pennsylvania for Environmental Health News and she is the author of "A New War On Cancer: The Unlikely Heroes Revolutionizing Prevention". (Photo courtesy of Kristina Marusic)

MARUSIC: Appalachia is already home to a really dense network of oil- and gas-related infrastructure. We have fracking and conventional oil and gas wells, pipelines, established transportation routes, and we also have a huge plastic manufacturing plant here in Western Pennsylvania that's owned by Shell. So it's really convenient to put another piece of that network close by so that those resources can kind of overlap. And it's also important to know that this region tends to have fewer environmental regulations, particularly when it comes to, you know, oil and gas and oil- and gas-adjacent industries, because we're already so set up for extractive industries here. Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia are three of 24 states that have recently passed legislation to reclassify chemical recycling facilities from waste processing facilities to manufacturing facilities. And that's a really important change, it means that they're subjected to fewer regulations and less regulatory oversight. And it also makes these types of facilities more eligible for public subsidies at the local and state and federal level. And those bills in the 24 states that have passed them are something that the American Chemistry Council and the plastics industry is lobbying for, to try and make it easier for these types of facilities to be constructed.

DOERING: Christina Marusic is a journalist for Environmental Health News. Thanks so much for joining us again.

MARUSIC: Thank you so much for having me.

DOERING: We reached out to the American Chemistry Council to ask about its lobbying efforts and received a response that reads in part:

“So far, 25 states regulate advanced recycling facilities as manufacturers. These modernized regulations are not only more appropriate from a technological perspective, but they can provide certainty to incentivize increased investment in advanced recycling technologies, green jobs, and more sustainable manufacturing.”

We’ll post the full response, as well as Encina’s statement about ending its plans to build in Pennsylvania, on the Living on Earth website, loe.org.

Related links:

- EHN | “Pennsylvania’s First Proposed Chemical Recycling Plant Canceled”

- Inside Climate News | “A Giant Plastics Chemical Recycling Plant Planned for Pennsylvania Died After Two Years. What Happened?”

- EHN | “Listen: Why Communities in Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia Are Fighting Chemical Recycling Plants”

- EHN | “Residents Fear Pennsylvania, West Virginia Chemical Recycling Proposals Will Deepen Fossil Fuel Ties and Pollution Problems”

- EHN | “Paused Ohio Chemical Recycling Plant Puts Spotlight on Appalachia as “Prime Target” for the Controversial Practice”

- Allegheny Front | “A New Investigation Shows State Regulators Have Struggled to Keep Up With Pollution Events at Shell’s Petrochemical Plant in Beaver County”

- Learn more about Kristina Marusic

[MUSIC: Doc & Merle Watson, “Home Sweet Home” on Home Sweet Home, Traditional American/arr.Doc Watson, Sugar Hill Records]

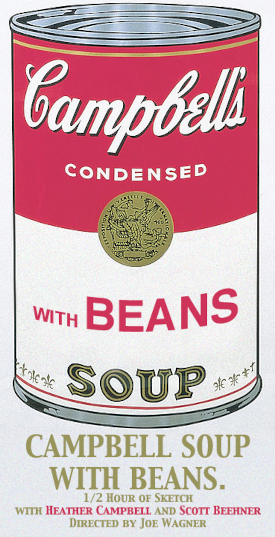

Lake Erie Sickly Green

Lake Erie provides drinking water for about 11 million people. (Photo: Jackie, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

O’NEILL: Lake Erie has been at the forefront of a national water pollution crisis for decades. And in March, the United States Department of Justice and a couple of environmental groups filed two lawsuits against the Campbell Soup Company. They allege that the company’s manufacturing plant in Napoleon, Ohio has allowed polluted wastewater to flow into the Maumee River and then into Lake Erie. This pollution is on top of a more widespread problem of runoff from nearby agriculture and livestock operations. The resulting bacteria found in the lake include E. coli, linked to human health concerns like diarrheal diseases. And the phosphorus-rich wastewater also feeds algal blooms that turn the water green – and we don’t mean eco-friendly. For more, we turn now to Lake Erie Waterkeeper Sandy Bihn. Sandy, welcome to Living on Earth!

BINH: Thank you. Thank you for having me here.

O'NEILL: For those of us who haven't been to the Great Lakes region, tell us about Lake Erie and why a clean Lake Erie is so important.

BINH: Well, the Great Lakes are an amazing surface body of water, they provide drinking water for 40 million people. And Lake Erie itself provides drinking water for 11 million people. So it's one of the five Great Lakes and the greatest freshwater source in the world. And so--and Lake Erie is the southernmost of the Great Lakes. The shallowest, the warmest, and it has three basins. And here in the western basin, it is the most vulnerable, so it gets sick easier because it's shallow and warm, but can also heal quicker, because it turns over so much.

O'NEILL: And as I understand it, at one point, Lake Erie was considered sort of a textbook example of the Clean Water Act at work.

BINH: Absolutely. We were the comeback lake, right? The body of water. We were the example throughout the world. So in the 50s and 60s, the Clean Water Act happened and they took the toxics out of the waters through the Clean Water Act. And also along with that, that's not often talked about, is the algae that was in Lake Erie that was so putrid and awful. They took phosphorus out of laundry detergent, and 28 states passed a ban to have the phosphorus out of the detergent. And not long after that happened, Lake Erie was once again blue and healthy and thrived, and the walleye came back, the wall--it's now the walleye fishing capital of the world. And then in the 90s, all of a sudden she started--not started, she almost instantly turned green again. And that happened when the practice of confining animals in small spaces in barns, in this case dairy cows, came to our area, and the liquid manure was applied, and almost instantly the lake turned green. And there's not much being done to manage that manure, because it's agriculture. And the laws for human waste are in place and require human waste to be treated. But you know, traditionally, animals were pastured, and they were spread over millions of acres, their manure was, and it wasn't a problem. But now that they're confining them, if you look at what we call NOAA MODIS maps right now, you would see a very turbid green lake very early in the season.

Manure from confined animal feeding operations (CAFOs) has also contributed high amounts of phosphorus to Lake Erie. (Photo: MPCA, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

O'NEILL: And now the Campbell's Soup Company is being sued for violating the Clean Water Act. What's going on there?

BINH: It's a sad story, actually. So when you put too much phosphorus in the water, it creates harmful algae that creates microsystem and toxins that have health consequences, and obviously are problems for the water and swimming and all that. The difference between manure being applied in a CAFO, or in a confined animal feeding operation, is it's spread over the land. And especially for cow and pig manure. It's liquid. You know, it doesn't take a rocket scientist to know that when you apply liquid on a field, it's going to go to the drains and it's going to come into the waterways, the streams and the lake. But other waste comes to waterways through a pipe, known as point sources. And Campbell's is one of those. It's a point source. It's a processing plant for their soups and other products. And so that water comes into the Maumee river and into Lake Erie. Sadly, they have an excess phosphorus discharge that comes into the Maumee. And they also have 400 acres of a field where they spread their wastewater, which has excess phosphorus coming into the lake. And it's helping to turn Lake Erie green. They've had violations for over five years, maybe over 10 or more. And the state of Ohio nor the federal government has called them out. Although now, Environment America, Lake Erie Waterkeeper and the U.S. Department of Justice have taken it to court and are requiring something to be done. Ohio EPA remains silent on this, which is really sad.

O'NEILL: And so what has been Campbell's response to the concerns after they've been raised by environmental groups?

BINH: They're saying they'll fix it. And they'll take care of it. So that's happening now. And there's negotiations to settle it. And there's also a component of that, that the economic benefit that they've derived from putting too much in the lake instead of treating it, which has a cost to it, that they'll have to do a project or something that will mitigate that--what they've done for past years, and that's just being discussed now and there's not much more detail I can give you.

Campbell’s Soup is being sued for allegedly violating the Clean Water Act. The complaints say excess phosphorus in the company’s wastewater is polluting Lake Erie. (Photo: Heather Anne Campbell, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND)

O'NEILL: Okay, so let's talk now about solutions. What is being proposed that can help mitigate some of this harm and hopefully return Lake Erie to a cleaner state, whether that be in response to the liquid manure spreading or in response to Campbell?

BINH: Well, they're two separate issues. Campbell has a pipe that they can treat it and they can clearly stop very soon if they simply put in the equipment that's needed. And they can stop the excess phosphorus and other pollutants from going in the lake, that's easy to do. But the manure problem, the liquid manure and solid manure from the confined animal feeding operations, the big ones, it can be done. It just takes the political will to do it. And meat and dairy is the most powerful lobbying group in the U.S.—right up at the top in terms of a lot of money. And so right now in this watershed we have an estimated 400,000 dairy cows, 1.8 million hogs, 24 million chickens, almost all of that being in these confined animal feeding operations being applied close to the barns, and the federal government, USDA allows two to four times more phosphorus to be put on the ground in the manure than is needed by the crops. So it doesn't take a rocket scientist to know that doesn't compute. But meat and dairy, this is their profit margin, right? This is how they make more money, is to pass along and put that manure the cheapest way, which is on the fields untreated. And so that's wrong, any more than a failing septic system shouldn't be allowed, any more than a sewer plant shouldn't be allowed to overflow. Why are they allowed to put excess manure on the fields, far more than they need?

O'NEILL: It seems to me that as things stand currently, lakeside communities, waterfront communities might feel like they're being asked to make a choice between clean water and manufacturing or agriculture, you know, a healthy environment or a healthy economy. What do you make of that?

Excess phosphorus can cause harmful algal blooms and pollute drinking water. (Photo: tuchodi, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

BINH: I think that's a big myth. You know, just because when the Clean Water Act was passed, industries found a way not to put all those chemicals, not to put the metals in the water. And they internalize those costs. We have clean water, those businesses are there today. I mean, a great example is Procter & Gamble. They made the same argument you're making now for manure, for phosphorus and laundry detergent. You know, you're going to put us out of business. It's not going to work. And I've got quotes from them in studying the history of this. And you know what, we still have Tide today. And we have clean water. So they need to internalize their costs. But the problem is, it shouldn't be borne by the local farmer. It should be borne by the Tysons, the Cargills, the Smithfields and all the big people that can afford to internalize that cost and make it right. They shouldn't be lobbying to continue to pollute the ground, when in fact they could solve the problem and find the technology and what's needed not to have this happen.

O'NEILL: Sandy Binh has been Lake Erie Waterkeeper since 2004. Sandy, thank you so much for taking the time with me today.

BINH: Thank you.

O’NEILL: We reached out to the Campbell Soup Company for a response that reads in part:

“We have taken a number of steps to improve our existing wastewater management operations and will continue to take immediate action to address this issue.”

We’ll post the full statement on the Living on Earth website, loe.org. We also contacted the Ohio Dairy Producers Association for comment but did not hear back in time for broadcast.

Full Campbell Soup Company Statement: "We have taken a number of steps to improve our existing wastewater management operations and will continue to take immediate action to address this issue. We have retained independent experts to help implement short-term improvements and have capital investments planned to resolve this issue permanently. We take this matter seriously and will continue to work with regulators and other stakeholders to improve our operations and comply with all environmental regulations."

Related links:

- The lawsuit filed against Campbell Soup

- Reuters | “Campbell Soup Sued Over E. coli, Phosphorous Discharges at Ohio Plant”

- Environmental Law and Policy Center |“Ohio Campbell’s Soup Facility is M’m M’m Bad”

- Learn more about Lake Erie WaterKeeper

- Read more about Sandy Binh

- Meat and Poultry Processing in Lake Erie Basin

[MUSIC: Joshua Bell & Edgar Meyer, “OK, All Right” on Short Trip Home, by Edgar Meyer, Sony Classical]

DOERING: Coming up, harvesting lithium for batteries from deep underground. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth. Stick around!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: New York Woodwind Quintet, “Finale from Quintet for Winds in E flat, Op. 88 No. 2,” by Anton Reicha, Boston Skyline Records]

Lithium from Deep Underground

The open pit of the world’s largest hard-rock lithium mine, located in Western Australia. Hard rock mines can cover many acres of land and damage local ecosystems. (Photo: Calistemon, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

O’NEILL: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

The lightest metal, lithium plays a key role in the global shift towards clean transportation, since it’s so useful in electric vehicle batteries. At the moment, most lithium comes from salt-flat brines and hard rock ores in Australia, Chile, and China, though the U.S. is trying to compete as well. Despite the clean energy benefits of lithium, current extraction methods come with environmental costs and health risks. Hard rock mines use heavy machinery often powered by fossil fuels and requires land to be cleared. Evaporation ponds for salt-flat brines can take up thousands of acres of land and leave behind toxic residues. One alternative that some companies are exploring is a process called direct lithium extraction, or DLE, that taps into brine water deep in the Earth. Wyatt Myskow is an investigative fellow at our media partner Inside Climate News, and he visited one proposed direct lithium extraction site in the little town of Green River, Utah.

MYSKOW: Essentially imagine like an inland sea a million years ago got trapped underground. And we don't really use it for anything. Because it's really deep in the ground, it's not safe to drink. But it can contain these trace elements of minerals like lithium. What direct lithium extraction proposes to do--and it varies from operation to operation, it's really a catch-all term—but they all involve essentially digging a well that's going to pull that water from these deep brine aquifers up to the surface, where it's going to undergo what we call an ion exchange, which is a chemical process that essentially swaps the ions of the lithium with the similarly charged ions of something not valuable to extract that lithium from the brine water. And then that brine water can be sent back into the earth. So in theory, it doesn't require as much water because the water goes back into the earth—this brine water at least. And it can require a lot less land, you don't need thousands of acres, you don't need giant holes in the ground to do this, you just need a couple of wells and a processing facility. And a really big factor that makes it an exciting option and one that might be more friendly for the environment is that it can exist with other infrastructure. So for example, at the Salton Sea in California, underneath the Salton Sea is a geothermal brine aquifer. And this water is very hot, we use it to create energy. And those facilities bring that water up to do the geothermal process. What they're proposing is, okay, we're already bringing it up, why not extract the lithium from this water, and get both the geothermal energy from it and also lithium. And a lot of these operations are not just proposing to extract lithium, but also other minerals that are found in these aquifers, to know that, hey, we're not just gonna sell lithium, we're gonna sell this as well.

DOERING: So I've also heard about these evaporation ponds that are sometimes used in lithium extraction. What are those, and how does direct lithium extraction compare?

Lithium evaporation ponds near Silver Peak, Nevada in 2010. Direct lithium extraction is an alternative method to evaporation ponds in which the brine water containing the lithium does not need to be evaporated, but can instead be returned underground after the lithium is extracted through chemical processes. (Photo: Doc Searls, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

MYSKOW: So evaporation ponds involve also bringing that brine water up to the surface, where we put it into manmade ponds that can be pretty big. The water goes there, and the sun evaporates the water, and what's left behind is the lithium. The big difference between the two is that in an evaporation pond, that brine water is now gone, right? It's been evaporated, whereas with direct lithium extraction, that water is sent back into the ground, so it doesn't use that water.

DOERING: So some of this sounds pretty promising, potentially using less land and maybe even less water. But as I understand it, not everyone is enthusiastic about direct lithium extraction. Why is that?

MYSKOW: So even though direct lithium extraction can put the brine water back into the earth and not consume it, it can still require a lot of fresh water. Every one of these DLE operations uses a little bit different technology, a little bit different operations. And a lot of it's not really publicly available right now of how these things work. But some studies have been done that show that in some cases, they can use a lot of fresh water, more fresh water, which is the stuff we drink, then other lithium extraction methods. And so that's a big concern, especially in the Southwest, where a lot of these lithium mines are being proposed. We're in a drought down here, and there's not a ton of water, and any drop of water is going to be debated. And so environmentalists and locals in these various places like Green River, Utah, where we're seeing these operations being proposed, are concerned about how much water will be used. Another big concern is that this technology has never been used at scale in the real world. There has been lots of pilots, lots of testing for decades, but it hasn't been used the same way hard rock mining has been done. And so there's a lot of unknowns over how much impact this will really have, how much water will really be needed. And what's the impacts of removing this lithium from this water. These brine aquifers, even though they're not used for drinking water, they can be connected to aquifers that are used for human use. And that means that if you pull too much water out of one aquifer, the other one will see impacts as well. And you'll lower that water table. And that's again the concern with this direct lithium extraction operation being proposed in Green River, is that we don't know a ton about how interconnected these aquifers are. Is it connected to the Green River? It's a tributary of the Colorado, millions of people rely on the water in that river. And people really—they feel like they're being the guinea pigs for this, and they don't want to be.

The small town of Green River, Utah is the site of a proposed direct lithium extraction operation. (Photo: Jimmy Emerson, DVM, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: By the way, how much fresh water is it estimated that direct lithium extraction could require?

MYSKOW: It varies from operation to operation. The fresh water is measured in what we call acre feet, which is essentially how much water is needed to cover one acre of land under one foot of water. In Utah, that's enough water for two households for one year. So the Green River project, for example, they've acquired around 2,500 acre feet of fresh water so far to use for the process. They may use a little bit more than that. Some of the projects in the Salton Sea are more in the range of around 6,500 acre feet. Some studies have shown that maybe it might be tens of thousands of acre feet, depending how long the process is and just the technology needed. But it's certainly enough water to where a community would be concerned about the amount of water needed for this.

DOERING: Yeah. So they would be pumping this brine deep from the earth, but also potentially using water from the Green River and from other freshwater sources to be able to process the lithium out. Why might this method of using direct lithium extraction need potentially so much water?

MYSKOW: So in the Green River example, they use fresh water to essentially flush out the lithium once they've undergone the ion exchange. They use these resin beads to soak up the lithium. They need to get that lithium now out of those resin beads. And that's where the Green River water comes into play. Sometimes that fresh water is just needed for facility purposes, like keeping everything cool and at temp—there’s just a lot of different uses. It just varies from operation to operation.

DOERING: Now in the town of Green River, Utah, there are plans for a direct lithium extraction site, but the project is still in the testing stages. In your article, you talk about a well blowout that occurred there when the company began to drill. What exactly happened?

A melon stand in Green River, Utah. The town is known for its melons and has a yearly melon festival. Some residents worry that the proposed direct lithium extraction project in the town could affect freshwater supplies and impact agriculture there. (Photo: Kristina D.C. Hoeppner, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

MYSKOW: So the lithium they're targeting in this brine aquifer in Green River, Utah is about 10,000 feet underground. And right now they're undergoing, like you said, these testing operations, just trying to find out the quality of the lithium, see what's there. And they were drilling in a well, and they went around 1,500 feet, and they encountered pockets of carbon dioxide and also more water than they were expecting. And that caused the well to blow out. And that led to water of course rushing to the surface, they had to pump that water up, take it to a storage facility, divert it so it didn't go into any nearby washes or the river itself. And that caused a lot of concern from residents because, for months, they have been asking questions about what happens if a well blows out, how will this impact local water supplies, and at 1,500 feet, this water wasn't toxic, it was safe to drink. But at 10,000 feet, where you start running into even more gases, even more high pressures, where a well blowout's even more likely, you know, that water is unsafe to drink, that water has impacts if you drink it or if it touches the local farms nearby or goes into the river. And their big question is, what happens if this happens again, essentially? How are we going to stop this? How are we going to make sure it doesn't impact other uses? And so there's a lot of concern over that.

DOERING: So what kinds of economic prospects of a project like the one in Green River, Utah, are there? What's the economic situation of this, as I understand it, pretty small town, and what kind of jobs might come as a result of drilling for lithium there?

Wyatt Myskow is a reporter based in Phoenix, Arizona. He is the Roy W. Howard investigative fellow at Inside Climate News, where he covers water issues, development, public lands, wildfires and more. (Photo: Alex Gould)

MYSKOW: So Green River is a town of about 900 people. It's famous for its melon operations, they grow melons, they have a melon festival in the summer, they have signs about the melons, they have roadside attractions. So it's largely an agricultural community. And for years, there's been lots of developments being proposed in the area that residents are usually kind of skeptical of, stuff like a landfill, processing facilities, there used to be a nuclear facility in the area. There's a lot of stuff that, though it may have brought jobs, there were concerns over the impacts and how it would affect the community. This direct lithium extraction mine is no different. It's proposing around 500 construction jobs with an average salary of around $80,000 during construction, and then a permanent workforce of around 100 people with an average salary of $120,000. So that's quite a few jobs for this small community, and high paying jobs at that. And it would also raise millions in state and federal taxes. And so there's a lot of economic incentives. And for some residents, though they have this concern of, you know, what the impacts will be to the environment and how this may impact local water supplies, those high paying jobs are kind of hard to turn away. And this feels like though maybe a risky development in some ways, less risky than some of the other stuff that's been proposed in the past. But again, agriculture kind of runs this town. And as long as there's that concern over water, I think we'll see pushback from them about that.

DOERING: Wyatt Myskow is an investigative fellow at Inside Climate News. Thank you so much, Wyatt.

MYSKOW: Thanks for having me.

Related links:

- Read Wyatt Myskow’s article about direct lithium extraction for Inside Climate News

- AP News| “US Seeks New Lithium Sources as Demand for Batteries Grows”

- Washington Post | “How Lithium Gets From the Earth Into Your Electric Car”

- Wyatt Myskow’s reporting on Inside Climate News

- Read more from Wyatt Myskow

[MUSIC: Jeff Little, “Little Rock Getaway” on Jeff Little, public domain, JTL Music – Nashville]

The "Green Flash"

Mark Seth Lender captures the ‘Green Flash’ alongside Smeagull the Seagull. (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

O’NEILL: So Jenni – have you ever seen the elusive “green flash” at sunset or at sunrise?

DOERING: Oh, I’ve heard of that, but no, I’ve never seen it. You?

O’NEILL: Me neither. Add it to the bucket list, I guess? But Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence Mark Seth Lender has been lucky enough to catch it more than once.

The Green Flash

© 2023 Mark Seth Lender

All Rights Reserved

By proclivity, which is to say, with no heroic efforts or even an alarm clock, I’m an early riser. Most mornings I make a coffee and take it to the porch, and sit, and meditate, facing the sea. Then I watch the sun come up. My days can be frantic, like everyone else. These mornings are something in reserve. If I remember—if I remind myself—I can return to that morning frame of mind and calm down. I’m privileged in this. Sometimes, exceptionally so. This morning for the first time in months and months the air was clean. The wildfire smoke that’s been with us, this sick nitric acid orange all across the horizon… it wasn’t there. And the light had this clarity. It looked much colder than it was. And it was just beautiful. I finished my meditation, and looked toward the glow where the sun would rise and waited. When the sun comes up, just as the first inkling of the disk breaks the horizon, sometimes, if everything is just right, there is an incredibly brief, incredibly bright flash of green. It can happen at sunset too but in reverse, just as the sun disappears. It’s rare. In either case.

For centuries, mariners and those who live close by the sea have claimed to see a brilliant flash of intense green light, at sunrise or sunset, always and only over water. Science was long in doubt. So was Explorer in Residence Mark Seth Lender until he captured one on film. (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

This morning before sunrise, the sky was unusual in some way I can’t quite describe. It was this quality that captured my attention. I had the feeling this was a sunrise not to miss. All those elements, clear and bright and not too cold. I kept my eyes on the horizon where the sun would soon be. It’s so fast when you see it you are never sure, certainly not the first time or the second time. But this morning I saw the Green Flash for only the third time in my entire life, always over water, and in this instance for the first time in 40 years.

O’NEILL: That’s Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender.

Related links:

- Mark Seth Lender’s Website

- Slow-Motion Video of the Green Flash on NASA’s Astronomy Picture of the Day website

[MUSIC: Eric Tingstad, “Sunrise at Four Corners” on Southwest, by Eric Tingstad, Cheshire Records]

DOERING: Next time on the show, Bill Gates and other investors are banking on nuclear energy that uses liquid sodium to help power the future.

BUONGIORNO: Sodium can operate at a higher temperature. So it allows you to actually store the heat more efficiently on site and to modulate the electric power output, so that when the grid demands more power, you can sell more power. When the grid demands less power, you can basically keep storing the heat on site and selling that power later. So it's the ability of basically swinging up and down in power output that is allowed with this particular reactor design that would be more difficult with the traditional designs. This particular feature is important these days because there is quite a bit of variability on the grid because of the penetration of intermittent renewables like solar and wind. Sun doesn't always shine, wind doesn't always blow, so you have sort of again, ups and downs in what's generated, what the electricity is generated on the grid. And so this reactor, which is able to vary its power output, is particularly useful in that context.

DOERING: Nuclear to help power the clean energy transition, next week on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Eric Tingstad, “Sunrise at Four Corners” on Southwest, by Eric Tingstad, Cheshire Records]

DOERING: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Shanzay Asif, Paloma Beltran, Josh Croom, Karen Elterman, Swayam Gagneja, Sommer Heyman, Mattie Hibbs, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari.

O’NEILL: This week we thank Sarah Mahaney for all her hard work! Tom Tiger engineered our show. Allison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at loe.org, Apple Podcasts and YouTube Music, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments@loe.org. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth