May 10, 2024

Air Date: May 10, 2024

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

New Power Plant Rules

View the page for this story

To replace the Clean Power plan the Obama Administration failed to get past the courts the EPA published new rules for existing coal plants and new gas power plants that tighten standards for mercury emissions, wastewater, and coal ash and also curb coal plant CO2 emissions over time. Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran discusses with the rule with David Doniger, a former White House and EPA clean air official and attorney for the Natural Resources Defense Fund. (11:10)

Protecting India’s Forest

View the page for this story

The 2024 Goldman environmental prize winner from Asia mobilized his community to protect the Hasdeo Aranya forests in the state of Chhattisgarh from coal mining. These forests are known as the “lungs of Chhattisgarh”, and a report from the Wildlife Institute of India estimated that around two-thirds of local annual income is tied to forest resources. Living on Earth’s Aysnley O’Neill spoke to Alok Shukla through a translator about his successful anti-mining campaign. (09:27)

Fighting Pollution Linked to Online Shopping

View the page for this story

The 2024 Goldman Environmental Prize recipient from North America, Andrea Vidaurre led a campaign that convinced the California Air Resources Board to make rules designed to decrease air pollution and lead to zero-emission trucking by 2036. These rules are aimed at reducing diesel pollution related to the online shopping industry. Andrea joined Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran to discuss how these new rules are aimed at reducing toxic air pollution in the Inland Empire of Southern California. (11:18)

From the History Books

View the page for this story

Living on Earth contributor Peter Dykstra joins Host Aynsley O’Neill for a trip back in time to a massive dust storm that covered the United States’ eastern seaboard in the 1930s, as well as the start of the Galapagos National Park in Ecuador. (02:58)

Plastic Pollution Treaty Talks

View the page for this story

The fourth meeting of UN talks aimed to address plastic pollution took place this April in Ottawa, Canada. The goal is to have a legally binding international agreement on plastics pollution by the end of 2024. Professor Maria Ivanova, Director of the School of Public Policy and Urban Affairs at Northeastern University joined Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran to give an update on what happened at these most recent talks. (09:00)

Wake! Up!: Paper Wasp

View the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence Mark Seth Lender aids a paper wasp trying to get outdoors. (01:32)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

240510 Transcript

HOSTS: Paloma Beltran, Aynsley O’Neill

GUESTS: David Doniger, Maria Ivanova, Alok Shukla, Andrea Vidaurre

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Mark Seth Lender

[THEME]

O’NEILL: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

O’NEILL: I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

The EPA strengthens regulations for coal and gas power plants.

DONIGER: Every time the power industry has been required to clean up its pollution, they have shouted, “We can't do it, it won't work.” And every time we called their bluff, they have performed. Now it's time to control the carbon dioxide that's overheating the whole world.

O’NEILL: Also, how grassroots activist Andrea Vidaurre successfully advocated to limit trucking and rail emissions.

VIDAURRE: Diesel also is known to cause respiratory issues for people that are older. And we have stories of people that have had double lung transplants or have to be connected to a breathing machine even though they've never smoked a day in their life, right? And that's from diesel.

O’NELL: These stories and more this week on Living on Earth - stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

New Power Plant Rules

Existing coal-fired power plants and new gas-fired power plants will be subject to the updated climate pollution standards set by the EPA. There are also a series of regulations that deal with other pollutants like wastewater and coal ash. (Photo: peggydavis66, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

O’NEILL: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

To replace the Clean Power Plan the Obama administration failed to get past the courts, the EPA has published new rules to fight global warming gases and other pollutants from existing coal-fired power plants and new gas ones. These updated rules tighten standards for the plants’ mercury emissions, wastewater, and coal ash. And coal power plants must significantly curb their CO2 emissions over time. Carbon capture and storage technology may be one way to meet those goals, with the help from the Inflation Reduction Act. But critics still question the viability and safety of CCS. Here to discuss the implications of the new EPA mandates is David Doniger, a former clean air expert for the White House and EPA, and now lead global warming attorney for the Natural Resources Defense Council. David, welcome back to Living on Earth!

DONIGER: Thank you. It's good to be back here.

BELTRAN: So the current administration's emissions reduction targets include reaching around 100% carbon pollution-free electricity by 2035, and achieving a net zero emission economy by 2050. To what extent will these new rules put us on track to reach those goals? And how big of a deal is this?

DONIGER: Well, this is a very big deal. With these rules, by 2035, EPA is projecting that the power sector will be about 75% less polluting than it was at its peak in 2005. It's not 100%. But it's a good solid step in the right direction. We have to do more, but this is a very big step in the right direction.

BELTRAN: And what are the potential public health benefits of these new rules?

DONIGER: Well, these are aimed at carbon dioxide. Carbon dioxide drives the warming of our planet. The warming of our planet is causing terrible storms, heat waves, stronger hurricanes, stronger floods, the oceans are hotter than they've ever been. And that's expected to drive really a bad hurricane season this year. So these events kill people, they hurt people, they make them sick, those are direct effects on our health.

The Biden-Harris Administration has set a goal of reaching 100% carbon-pollution-free electricity by 2035. The EPA predicts the new rules will get the country 75% of the way to that goal. (Photo: The White House, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

BELTRAN: And how will those plants actually meet these emission targets? What pathways do they have available for them to meet those goals?

DONIGER: Well, the way the Clean Air Act works, and the way the Supreme Court confirmed in 2022 that it works, is it directs EPA to set what are called performance standards, an emission rate, and the emission rate is based on the best system of emission reduction, the best technology. In the case of power plants, the most effective technology is to capture the carbon and keep it from going into the atmosphere and store it deep underground. Now, a company doesn't have to use that. Once EPA sets the standard, it becomes the company's choice or the state's choice how they would comply. They can comply by retrofitting the plant or building a new plant with this technology. If they're really smart, they'll come up with some other technology, that's fine too, if it meets the same performance. Or they can choose, as many of the companies are already doing, to replace these plants. A lot of coal plants are already retiring, and more of them are expected to retire. Some of them will stay in operation, you know, all the way through the next decade into the 2040s. And those are the plants which EPA is saying, if you want to keep them running that long, you've got to control the pollution. If you want to retire them sooner, there might be lesser requirements or even no requirements for the plants that are going to close in the nearest term. And you might as a power company choose to replace them with wind and solar, batteries, other forms of meeting the power needs. But those choices are for the companies and maybe for the states. The EPA just sets out the, the yardstick, the performance measure.

The Petra Nova carbon capture and storage system in Texas. With financial help from the Inflation Reduction Act, some coal plants may choose to implement carbon capture and storage procedures to meet the standards. (Photo: eia.gov, public domain)

BELTRAN: And what are the incentives available for these different emissions reduction pathways?

DONIGER: So that's what's really different this time around. In 2022, Congress passed the Inflation Reduction Act, a major climate law. And that added to the incentives of the Infrastructure Law passed the year before, a couple other laws. The upshot of it is, is not only do we have EPA standards, which are limiting the pollution, but you have enormous amounts of federal tax credits and incentives available to help the companies do this. So the cost of meeting a standard with putting carbon capture and storage on an old coal plant or a new gas plant is much cheaper because of the help that the federal government is providing. And that's different from the way things were done in the past. When we controlled sulfur dioxide, or oxides of nitrogen, that was done with standards, there were no tax credits and so on to help the companies. This time around, you have the standards and the incentives working together.

BELTRAN: You know, critics of carbon capture and storage say it's not a reliable technology yet, and that it's sort of a Band-Aid on the root of the problem. What's your response to that?

DONIGER: Well, you have to look at the history of each of these kinds of pollution controls, and they start out as demonstrations that the companies don't really want to do but they get government grants to try to demonstrate that the technology works. Generally then, they don't deploy it, because they don't have to, until there's a standard. Well that's what's happened here with carbon capture. There's been demonstration projects. There are two coal-fired power plants and one in Texas, and one in Saskatchewan, Canada that have been equipped with this technology and are running it over the long term. It's performing up to the standards that EPA is requiring. There are many projects on other kinds of industries with analogous technology. We know this is going to work. But it won't be deployed unless there is a requirement, unless there is a standard. Every time the power industry has been required to clean up its pollution, they have shouted, “We can't do it, it won't work, you'll kill the power system, you won't have electricity.” And every time we've called their bluff, they have performed, controlled the sulfur dioxide, controlled the oxides of nitrogen, and controlled the mercury. Now it's time to control the carbon dioxide that's overheating the whole world.

West Virginia’s Attorney General, Patrick Morrissey. Twenty-five states, led by West Virginia and Indiana, filed a petition challenging the EPA rules in the First Circuit Court of Appeals in DC. (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

BELTRAN: And what kind of legal arguments could be made against these new rules? And in your view, how strong are the EPA's potential defenses against those attacks?

DONIGER: Well, EPA is on a very strong legal ground. They're following the pathway that the Supreme Court said is the traditional approach to setting pollution control standards. The Supreme Court said this in a case called West Virginia versus EPA in 2022. They knocked down a novel approach that EPA had chosen during the Obama administration. But they said there's a traditional pathway that you've followed in the past, which is to set standards based on best technology as retrofitted to existing plants. And you can do that. So EPA is following that pathway. It's not just that, though, because Congress right after that decision, Congress passed the Inflation Reduction Act, the climate law. And that law did two really important things. First, it created all these tax credits, billions of dollars of incentives, to buy down the cost of installing this technology. So it's much cheaper for the companies that use it, and for their customers. The second thing it did is it amended the Clean Air Act and told EPA, go write another standard, following the instructions you just got from the Supreme Court. So this is what EPA has done. They're operating under a Supreme Court decision and a new act of Congress. We know we're going to get a lawsuit from West Virginia and other red state attorneys general. And they will say, this is the same old wine in a new bottle, it's the same thing. It should be struck down for the same reasons the last one was. And what they're ignoring is, the Supreme Court said, here's what you can't do. But here's what you can do, and follow the traditional approach, you'll be fine. The other thing they'll say is, this technology isn't adequately demonstrated. But it's proven in examples. And there's time allowed to build out the projects. And everything will be ready in 2032 when the deadline comes. So EPA is allowed to look forward to the development and deployment of the technology. And they have to leave enough time. And they have to show that it can be done and that the cost is within reason. And they have shown all these things.

BELTRAN: And David, this is an election year. To what extent would these rules be able to change under a new administration? You know, what power does a new administration have when it comes to changing these rules? And what steps would be needed in order to roll them back?

DONIGER: Well, if these hold up in the court, and I think they will, then they're on the books. They are the law of the land. The way any administration changes regulations, they have to go through the same process to take the regulation down as it took to build the regulation up, which means they have to make a proposal, they have to take public comment, they have to make a reasoned decision that is justified under the Clean Air Act. And then they have to defend it if somebody sues them in court. When the previous administration tried to repeal environmental regulations, they did not do very well in court. They lost lots and lots of cases. So whoever's the president, whoever's in charge has to follow the Clean Air Act, has to follow the law.

BELTRAN: What do these rules not cover? What's left to be done?

Former White House and EPA clean air official David Doniger is a Senior Attorney and Strategist for the Natural Resources Defense Council (Photo: Rebecca Greenfield for NRDC)

DONIGER: Our goal has to be to get to a carbon emission-free electric system. The EPA rules will get us about 75% of the way there. That's a lot. But it's not 100%. So there's more to do. Partly that's to cover the existing gas plants that aren't yet covered by this rule. And it's partly to figure out how to hasten the transition that we're in to a fully renewable power plant system, or at least a power plant system where if you're burning fossil fuels, you're capturing the carbon so it's not going into the air. So there's a ways to go, but this is a major step forward.

BELTRAN: David Doniger is a senior attorney and strategist at the Natural Resources Defense Council. Thanks for joining us.

DONIGER: Thank you very much.

BELTRAN: After our recording with David Doniger, 25 states led by West Virginia and Indiana challenged the EPA’s new power plant rules in federal appeals court, saying:

“Petitioners will show the final rule exceeds the agency’s statutory authority and is otherwise arbitrary, capricious, an abuse of discretion and not in accordance with law.”

Related links:

- EPA | “Biden-Harris Administration Finalizes Suite of Standards to Reduce Pollution from Fossil Fuel-Fired Power Plants”

- Read the EPA’s new standards

- Petition against the rule filed by 25 Republican States in DC at the U.S. First Circuit Court of Appeals

[MUSIC: Chris Pandolfi, “Open C” on Looking Glass, by Chris Pandolfi, Sugar Hill Records]

O’NEILL: Just after the break, a pair of the Goldman Environmental Prize’s newest award-winning activists. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Ron Carter/Gerry Gibbs/Kenny Barron, “Reasons” on Jazz Interpretations of R&B Classics, by Earth, Wind & Fire, Whaling City Sound]

Protecting India’s Forest

The 2024 Goldman Prize winner for Asia, Alok Shukla. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

BELTRAN: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Paloma Beltran.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

Each spring, the Goldman Environmental Prize gives its prestigious awards to activists from every occupied continent. Today, we’ll start off our coverage of these winners with Alok Shukla. He lives in the Indian state of Chhattisgarh, whose Hasdeo Aranya forests were being targeted by coal interests for mining. These forests are known as the “lungs of Chhattisgarh,” and a report from the Wildlife Institute of India estimated that around two-thirds of local annual income is tied to forest resources. So Alok mobilized the local community, and thanks in part to his campaign, Chhattisgarh has now broadly banned mining in the Hasdeo Aranya forests. I spoke to Alok through his translator to ask him more about the Chhattisgarh region and its connection to the coal mining industry.

TRANSLATOR: Coal is connected to people's lives, livelihoods, and culture. Naturally, coal has a lot of multi-dimensional impacts. The startling thing in India is that coal is found beneath the densest forests, beneath some of the most biodiversity-rich areas, and is integrally found in regions of tribal populations. So there are issues of displacement, there are issues of health, there are issues of groundwater depletion, and obviously, destruction of forests and wildlife and biodiversity.

O'NEILL: And you're a convener with Chhattisgarh Bachao Andolan, the Save Chhattisgarh Movement. What is this group and what work do you do with them?

TRANSLATOR: So Chhattisgarh Bachao Andolan is a state-level alliance of people's movements working on issues of farmers, tribal population, laborers. So, largely all connected with the common theme of protection of constitutional rights, and ensuring democratic processes are upheld.

O'NEILL: Now we're here to talk about your work with the Hasdeo forests. What are these forests, and how important was it to protect them?

The Hasdeo Aranya forests of Chhattisgarh are some of the most biodiversity-rich in all of India. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

TRANSLATOR: So, it takes just one visit to Hasdeo to fall in love with these forests. This is some of the most beautiful and the densest forest patches in central India. It's about 1876 square kilometers of natural forests. It's biodiversity-rich, elephant reserve, habitat of several endangered species like tiger and irrigates about four lakh hectares of land across the central Indian state of Chhattisgarh. In a sense, Hasdeo represents a microcosm of all the environmental and social justice issues across India and across other parts of the world. Because it is a struggle to save the lives, livelihood, and identity of not only the indigenous population, but also humanity at large.

O'NEILL: As I understand it, there were 21 coal mines that were proposed for the region in the year 2020. And you took it upon yourself to organize the local community to fight these proposed mines and protect the forest from future mining as well. How did you go about doing this?

Alok Shukla says that Chhattisgarh's Hasdeo forests are connected to every single Indian, particularly as a source of fresh air and clean water. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

TRANSLATOR: Since 2012, for close to over a decade now, local communities have been protecting the forests. Some of the key strategies. So number one, it's not just a struggle for one mine or one village affected by that mine. It's actually a collective struggle. So the first step really was forming a collective movement, where it's a fight for all the mines that are in that area. Number two, leverage all the constitutional means and democratic avenues available under India's constitution. The people of Hasdeo over the last decade have kind of leveraged every single platform, whether it is on the streets, or through the letters, whether it is representations, manifestos, petitions, sit-in protests, political advocacy, they've kind of explored all possible means. And the historic moment here was actually a 300-kilometer foot march that the local Adivasis undertook to the state capitol to meet the chief ministers and the governor of the state, following which, the Lemru Elephant Reserve was declared, which protected a large part of the forest. And followed by a unanimous all-party assembly resolution by the state government in declaring their intention not to do that. It's a hallmark of Hasdeo protests that they have been able to influence policy, gain political legitimacy, and in recent times, it is quite unique because they have been able to attract solidarity from every cross section of the society. It's not just a struggle for rural villages that are going to be displaced by it. It's got connected to every single Indian, in a way, because it's linked to the lungs of Chhattisgarh. So everybody's breath. It's connected to water. So in some sense, it attracted a broad cross solidarity, which is one of the hallmarks of the movement.

TRANSLATOR: And it seemed to me like social media and the internet played a huge role in this sort of coalition building. How did that factor into your approach?

TRANSLATOR: Media has played a huge role in the movement. It's been a conscious part of the movement's strategy, but also, whether it's social media or the mainstream media, it has touched the lives of so many other Indian citizens simply because the media actually helped amplify the voices. One reason why medias actually found interest in the [INDISTINCT], they saw the genuineness of the movement, they saw the steely resolve that the people had on the ground. And the message was not about just Hasdeo. The message was about how do we save the lives of every single Indian, which are touched by these forests, because these are the lungs. The common Indian draws water from the same river sources. In some sense, it's not a struggle to save a few villages. It's a struggle to save life. It’s a struggle to save humanity, especially in this area of climate change.

Alok Shukla (right) stands at the edge of a mine. His activism led to the state government’s bipartisan agreement to stop the construction of 21 coal mines in the Hasdeo Aranya forests. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

O'NEILL: And so, in 2022, the Chattisgarh government adopted a resolution that banned mining in these forests. What does that mean both for the area's ecosystem, but also for India's environmental activism movement?

TRANSLATOR: Thank you for asking that question. So it has a huge implication. Obviously, it protects this very, very rich ecosystem. Although the threat still remains, while a large part of the Hasdeo ecosystem has been conserved, there is an ongoing threat in some part of the forest. And the community is still resisting against that. But more importantly, to your second part, it represents a historic moment for Indian environmental activism. Because it's really the first time where the entire state legislative assembly, all the political parties came together to pass a unanimous resolution banning mining, which is quite a landmark moment, which itself is a testament to the genuineness of the struggle, to the awareness that rising Indian environmental youth and everybody is facing now, given the current era of climate change, that it is important to come together to preserve and protect such rich pristine forests. So this, I think, has been the biggest success of Hasdeo. They have not only achieved success for themselves, but also shown a path that several other struggle in. Not just in India, even globally, it's all a connected struggle. And this is where Hasdeo lends a powerful message that we all need to come together to forget our differences, and join the solidarity for saving our land, water, resources.

O'NEILL: I want to talk about what's next. What are your hopes for the future of Chattisgarh when it comes to the climate or even the future of India when it comes to the climate?

A crowd gathers in Hasdeo Aranya. Alok Shukla points to coalition building as one of the most crucial parts of his campaign to stop coal mining in the forests. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

TRANSLATOR: So this landmark success in saving Hasdeo, there are two parts to the local context. Currently, while a large part of Hasdeo has been saved, the efforts on the next step would be how do we rejuvenate these forests in a community-led approach so that the community's development, integrated development, can happen in coexistence with nature. And there is a small part of the forest where still the threat of coal mining still remains. The effort would be that no single tree should be cut. So that's one part of it. And in some sense, the next step is how do we take this message that Hasdeo has raised? It's raised the question that the development should not become a pretext for devastation of forests, ecosystems and local communities. So how do we take this message to the masses? Definitely, India is a fast, rapidly developing nation. So there are needs. So there is a need to figure out a way where we can adopt a people-centric approach to development, and based on a coexistence of human and nature.

O'NEILL: Why is winning this prize important to you and to your community?

TRANSLATOR: The message from Hasdeo is that even a small, marginalized, relatively powerless community can actually take on very, very powerful actors across the world and spread a message of peaceful coexistence with nature, using purely democratic means and a steely resolve. It also emphasizes the connections that different struggles all across the world need to forge together if we have to come together to fight this global reality of climate change. So that's really where we believe this Goldman Prize is an important platform.

O'NEILL: Alok Shukla is a Goldman Prize recipient and a convener with Chattisgarh Bachao Andolan. Thank you so much for taking the time today, and congratulations!

TRANSLATOR: Thank you very much. Thank you very much.

Related links:

- Learn more about Alok Shukla on the Goldman Prize website

- Watch a video summary of Alok’s work

- Find the Save Hasdeo movement on social media

[MUSIC: Relax Café Music, “Indian Sitar Instrumental Music”]

Fighting Pollution Linked to Online Shopping

The 2024 Goldman Prize winner for North America, Andrea Vidaurre. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

BELTRAN: The Inland Empire region of Southern California is home to over 4 million people. Located directly east of Los Angeles, the area also serves as a hub for logistical infrastructure. These include railroads, warehouses, trucks, and trains that make much of online shopping possible. The diesel pollution released by this industry has been linked to increased rates of asthma, cancer, and premature death among the predominately Latino residents of the area. Fortunately, Andrea Vidaurre stepped in to help. Andrea is an environmental activist, community organizer, and the North American winner of the 2024 Goldman Environmental Prize. She led a campaign to convince the California Air Resources Board to make rules designed to decrease air pollution and lead to zero-emission trucking by 2036. But part of the federal Clean Air Act limits state and local governments from regulating vehicle emissions. California has some exemptions, but these new rules are awaiting EPA approval. Andrea Vidaurre joins me now to explain more. Andrea, welcome to Living on Earth!

VIDAURRE: Hi there. Thanks for having me.

BELTRAN: So Andrea, I understand that you're from the Inland Empire in California and the director of the People's Collective for Environmental Justice. Please tell me about your community and the work that you do.

VIDAURRE: Yeah, so I am actually one of the co-founders of the People's Collective. I am the policy coordinator right now. And our organization was born in 2020. In the pandemic, we saw a lot of increase in online shopping. And what happened was, we were responding to what we already saw happening in our communities, which was the increase of logistics infrastructure, such as warehouses, the expansion of railroads, freeways, and most importantly, trucks and trains in our communities. And so we organize in the Inland Empire, we work with community groups, and we try to fight for the solutions that we want, which is we're trying to clean up the air quality, because we know that the air quality right now is what's hurting so many people living in the Inland Empire.

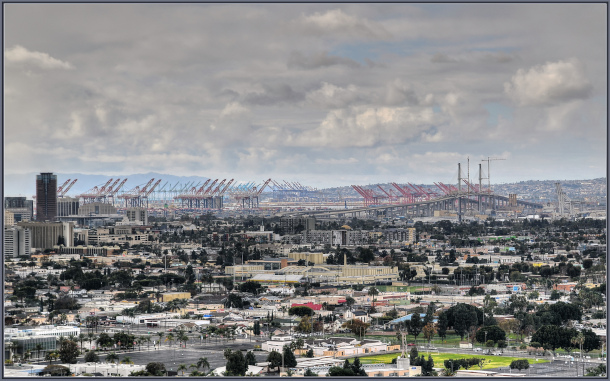

Los Angeles and Long Beach, California are the two busiest ports in the US and are linked to transportation networks that facilitate global commerce and drive economic growth for the region and beyond. (Photo: TD Lucas, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BELTRAN: I have actually seen part of the Long Beach port and driven to the Inland Empire. And it's surprising how huge it is. It's enormous.

VIDAURRE: It is huge. You're talking about giant concrete walls, giant concrete boxes, 1 million, 2 million, 3 million square feet. Sometimes they block the view of the mountains. Sometimes they block the view of the street. And in these warehouses, you know, you have trucks that come in and out every single day around the clock.

BELTRAN: I've heard that Riverside and San Bernardino counties are referred to as the “diesel death zone.” Why is that?

VIDAURRE: Yeah, that's a term that was created to talk about how diesel is deadly. There is no safe level of diesel to be breathing in. And we breathe it in every single day around the clock. And those come with real consequences. Children growing up with industrial allergies, and asthma, which keeps them away from going to school sometimes, which makes it hard to breathe when it's really hot outside. Diesel also is known to cause respiratory issues for people that are older, and the most vulnerable is our elderly community. And we have stories all over the place of people that have had double lung transplants, or have to be connected to a breathing machine, even though they've never smoked a day in their life, right? And that, that's from diesel, right, that's from the toxins in the air.

BELTRAN: And in 2018, you worked as a community organizer in areas experiencing increased air pollution and advocated for the California Air Resources Board, also known as CARB, to pass new rules. Tell us more about that.

VIDAURRE: Yeah, so we know that one of the solutions to dealing with the massive growth of the logistics industry is to deal with the air quality issues. And so CARB, the California Air Resources Board, their responsibility in the state of California, is to protect the public health and the air quality. And so communities for decades have been working to push government agencies to do something around air pollution. And really, I came in at a time, after decades of work from other environmental justice communities in the LA area and across the state who had been calling for zero emissions. They've been calling for pollution to be out of their neighborhoods. And that work really has led us to where we are now, which is we are at a place where with zero emissions is being talked about. The technology is being created. The infrastructure is being put. I mean, we're at a whole different place. And so 2018, when we started doing this work, CARB was still figuring out, like, should we go in this direction? Do we go all in? And it was really important for us to get involved and get our community involved. Because this is a lifesaving regulation. We know that the emissions reductions that we'll get from this rule will save lives, will prevent emergency room visits, will prevent asthma attacks, will prevent premature death.

BELTRAN: And as a result of all your hard work and the hard work of your community, the In-Use Locomotive rule and the California Advanced Clean Fleets rule was passed. What do these regulations entail?

VIDAURRE: Super fancy words, right? So for short, I call them the truck and the train rule, because that's what they are: the regulations that address truck emissions and train emissions. And so what these rules will do is for trucks, at least, it will require fleet owners, so these companies that have giant fleets of trucks, to transition over the next coming years to zero-emission trucks, to start replacing their diesel trucks with electric trucks. And then for the trains, very similar. Right now, the train system is incredibly unregulated. It's one of the most unregulated industries in our society, and they still operate using train technology that is 50, 60 years old. And so the train regulation will require some type of the trains to start being replaced sooner, which has never happened before.

BELTRAN: And how did you organize your local community to advocate for these regulations to be passed?

Freight trains across California currently use diesel engines. In response to the public health danger this posed to her local community, Andrea Vidaurre pushed for zero-emissions legislation in the transportation sector. (Photo: Picasa, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

VIDAURRE: I am part of a wonderful team at the People's Collective for Environmental Justice. I'm part of a larger network called the Moving Forward Network. We're all communities impacted by freight who are organizing in our neighborhoods, and we do it the way that it works for us. And so for us in the Inland Empire, it looks like us talking to our neighbors, talking to folks that are the most impacted, holding meetings, listening to people that are the most impacted and what they need, what they want to have a healthier life. We use a lot of the arts to organize our communities, right, hosting art events so that people can express themselves and what they're going through. But we also work with local communities so that they can host their own types of events, right, whether it's in a rancho, or whether it's in the back of someone's home, right. People were opening up their home so that their neighbors could come and learn about what's going on around truck and train emissions. We took all of that energy to CARB. We planned rallies outside of CARB. And we were putting our voices out into the community so that they could not be ignored.

BELTRAN: And I understand that you also organized something called “toxic tours,” which were tours of frontline communities in the Inland Empire so that CARB members and state legislators could witness firsthand the pollutions those communities were subjected to. What was the reaction?

VIDAURRE: The reaction of legislators and decision makers, when they're on toxic tours, is usually pretty silent, taking it all in. It's a lot of processing. For the most part, folks hear us two minutes, three minutes on the podium when we go up and we speak, right? And that's not enough time to tell you the full story, right? You need to see it; you need to breathe it; need to feel it. And so that's what we do, right? We kind of take people to experience a day in the life. And so we take people to those places, and so they hear directly from people impacted. And with that being like the evidence that they need, so that they can work on how strict these rules have to be. There is data. There is always going to be quantitative data. But qualitative data is just as important, hearing from voices on the ground.

BELTRAN: Altogether, the online shopping industry, the trucking and freight train industry are worth billions of dollars. What were some of the pushbacks or challenges you faced from industry?

VIDAURRE: Some of the pushbacks that we faced, I think, was around delays from the industry. I think we experienced a lot of attempts to delay the rulemaking, to say that it wasn't necessary, a lot of misinformation about the technology availability, a lot of legal threats from their side, a lot of money that they have, as you mentioned, to be able to shape the narrative. And so our work here is to disrupt that, right, and ground truth, all of this. The only way to do it is with this big power building, this movement building you need to do in your communities. We're able to overcome that with community organizing. We're able to overcome that when we are partnering with other groups and growing our power.

Andrea Vidaurre in conversation with her colleagues from the People’s Collective for Environmental Justice. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

BELTRAN: Transportation and the transportation industry is an intersectional issue across the world. What are some other things that come to mind when it comes to environmental justice issues that you're aware of and you're advocating for?

VIDAURRE: It's very important for us to get pollution out of our neighborhoods, to get diesel out of our neighborhoods. It's equally as important for us to make sure that a solution for us is not the problem for another community. And so as we think about electrification of our transportation system, and of a lot of our systems that we need so that we can make sure that we reduce climate pollution, we need to be thinking about critical mineral extraction and lithium extraction. And so at the same time we're fighting for electrification, we also need to be fighting for more public transportation, for more walkable cities, for ways that make sure that we are localizing more of our economy. So we are not so dependent on these systems that require a lot of transportation of our goods. And so just to say that, you know, this is a multi-prong approach, and that's the only way it will be if we truly are going to have environmental justice throughout all communities.

BELTRAN: What inspires you to keep going?

VIDAURRE: I'm inspired by the people around me to keep going. I'm inspired by the people that I work with. I'm inspired by elders and by youth; by elders who are like, “I don't know if I'm going to see the end of all of this, the benefits, but I'm gonna fight like I am. I fight for my kids and my grandkids.” I'm super inspired by the youth who want to like, fight, you know what I mean? Like they're fighting like, you know, for their lives, right, they get it. I'm also inspired by just this larger movement we're a part of, that is about changing the way our society operates. I'm constantly inspired by people who are taking on what seems like a big part problem, because we have to take on the big problems. We cannot take on the easy ones.

BELTRAN: Andrea Vidaurre is the North American winner of the 2024 Goldman Environmental Prize. Thank you, Andrea, for joining us.

VIDAURRE: Thank you.

Related links:

- More about Andrea Vidaurre’s journey

- More about the new regulations

- More about the People’s Collective for Environmental Justice

- More about the Moving Forward Network

[MUSIC: Michael Marc & The Gypsy Flamenco Masters, “Café Borrone” on Moody Road, Arrow Records]

O’NEILL: Coming up, the pressure is on to get a global treaty to address the problems of plastics before the end of 2024. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Michael Marc & The Gypsy Flamenco Masters, “Café Borrone” on Moody Road, Arrow Records]

From the History Books

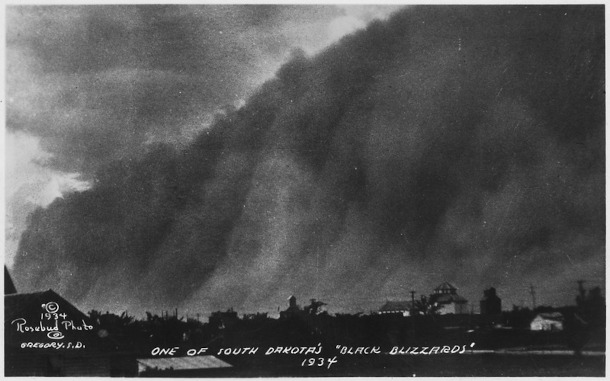

Dust Storms; "One of South Dakota's Black Blizzards, 1934". One of the immense "Black Blizzards" that ravaged the Great Plains region during the Dust Bowl era of the 1930s. Images like this raised awareness of the need for implementing sustainable soil management to prevent such environmental disasters in the future. (Photo: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

BELTRAN: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Paloma Beltran.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

And joining me now on the line is Peter Dykstra, the Living on Earth contributor who is going to bring us a few stories from the history books. Hey, Peter, what do you have for me?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Aynsley, we're gonna go back 90 years, it's hard to believe it's been 90 years already since the Great American Dustbowl, but on May 12, 1934, what at the time was the worst dust storm in U.S. history, swept off the Great Plains and eventually reached all the way to the East Coast. It was hard to see the Statue of Liberty from Manhattan Island. And in Washington, D.C., there were hearings underway to talk about soil erosion and the dust storm when Congress sees firsthand the damage done by drought and poor land use all the way over 1,000 miles away in the Midwest. The Soil Conservation Service was launched the next year.

O'NEILL: Well, the Soil Conservation Service. What was that? What did that do for us, Peter?

DYKSTRA: It was and is an educational arm that taught farmers how to take that soil and have a permanent positive impact on agriculture, rather than wasting the soil in a few years and having it blow all over the eastern half of North America.

O'NEILL: And 90 years later, still relevant today. Right, Peter?

DYKSTRA: It is. And it's something that farmers have been taught to live by not only in this country, but around the world.

O'NEILL: All right, and Peter, what else do you have for me this week?

A Marine iguana sunbathing on lava rocks in the Galapagos Islands. (Photo: Anthony C, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Another one that's almost 90 years old. May 14, 1936, the government of Ecuador established the forerunner of what would become the Galapagos National Park. The islands are known for their biodiversity and also their role in Charles Darwin's work, studying evolution. They became a haven for both science and ecotourism, except that the word “ecotourism” wouldn't be around for decades. The park's protected area was expanded in 1959.

O'NEILL: You know, Peter, I actually spent a couple of weeks in the Galapagos in college, and they're pretty serious about protecting their parks, they make sure that you are not bringing in any sort of invasive creatures. It might seem like a bit of overkill, but when you go there, it's really something else. It's like nothing you ever see anywhere else on Earth.

DYKSTRA: Right, and when you back up the value system that so many of us would like to see toward conservation, when you back it up with real money, because the Ecuadorians make money on protecting the environment in Galapagos.

A wooden sign welcoming visitors to the Charles Darwin Research Station in the Galapagos Island, named after the renowned naturalist. Darwin’s study of finches on the island ultimately provided key insights for the theory of evolution (Photo: Scott Ableman, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

O'NEILL: Alright, Peter. Well, thanks for that trip back in time. Peter Dykstra is a regular contributor to Living on Earth, and we will talk to you again soon.

DYKSTRA: Aynsley, thanks a lot. We'll talk to you soon.

O'NEILL: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth website. That's loe.org.

Related links:

- More about the Galapagos Conservation Trust

- More about the Dust Bowl and Soil Conservation

[MUSIC: Toby Walker, “Generosity Rag” on Hand Picked, by Toby Walker, Band In the Hand Records]

Plastic Pollution Treaty Talks

Plastic and other waste in the Himalaya mountains. The fourth of five UN plastics treaty talks aimed at addressing the growing global problem of plastic pollution took place in Ottawa, Canada in April. (Photo: Sylwia Bartyzel, Unsplash)

BELTRAN: Plastic waste has been found in the lowest parts of the oceans, at the top of Mt. Everest, and even as microplastics in the human placenta. This waste damages human health and, according to UNESCO, kills up to 100,000 marine mammals each year. A series of UN-led talks aims to address this problem with a legally binding agreement on plastic pollution. The fourth meeting in Ottawa this April began negotiations on the text of the treaty, and the pressure is on to finalize the agreement at the fifth and final meeting in Busan, South Korea, this November. Joining us now to discuss the plastic treaty is Professor Maria Ivanova, Director of the School of Public Policy and Urban Affairs at Northeastern University. She’s a former delegate who observed the session in Ottawa. Professor Ivanova, welcome back to Living on Earth!

IVANOVA: Thank you very much for having me back.

BELTRAN: This is the fourth out of five sessions of these plastic talks. What changes have you seen at this most recent conference in Ottawa?

IVANOVA: Indeed, it is the fourth and next-to-last intergovernmental gathering before we hope to have a treaty. I have observed a few changes. I can put them in three large buckets, but I have seen a change in narrative. The discussion on plastics started as a discussion on marine plastics. What Rwanda and Peru did was to change the narrative. So we are talking about the full life cycle of plastics, and the production and consumption and disposal of plastics, including primary plastic polymers. I have also seen a commitment to global goals for a treaty. Yes, we recognize we do need national action plans. But more and more countries see the necessity for robust and rigorous global goals. And the third bucket, I would say, of agreement and change is the implementation space. We see real commitment to creating a financial mechanism for the treaty. And that commitment also goes hand in hand with the recognition of the need to improve capacity in various countries, but also the capacity of civil society, of academia to engage and contribute to these discussions.

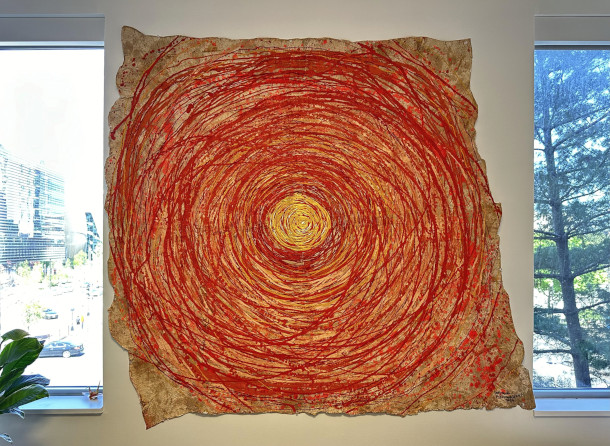

A painting by the Rwandan artist Innocent Nkurunziza hangs in Maria Ivanova’s office. Nkurunziza attended the Ottawa plastic treaty talks as a member of the Northeastern University observer delegation. (Photo: Courtesy of Maria Ivanova)

BELTRAN: Yeah, so let's talk about implementation. What are some concrete methods that have been proposed to limit plastic pollution?

IVANOVA: As you can imagine, there are producing countries—of oil and gas, of plastics, of polymers, of chemicals that go into plastics—, there are recipient countries around the world, and there is civil society and academia. So the ideas for concrete measures vary across the board. And to be frank, we have not seen "here is a concrete list of measures." But we are seeing very concrete commitment on the table—$15 million dollars from the United States—to challenge countries, to challenge stakeholders to come up with innovative solutions. And I think that is a very positive development.

BELTRAN: Reducing plastic pollution is the main topic of these talks. But now the idea of curbing plastic production is on the table. But this is a contentious topic. What kind of disagreements have there been around limiting plastic production? And what progress have you seen towards resolving them?

IVANOVA: You're absolutely right, this is one of the fault lines in the negotiations. Are we limiting plastic pollution? Are we eliminating plastic pollution, which is what the treaty title calls for? And how are we doing that? Countries like Rwanda and Peru state very clearly, to limit or to eliminate plastic pollution, we have to reduce the production of primary plastic, and that requires an overall decrease in production. Of course, countries that produce fossil fuels, or the raw materials for plastic—Saudi Arabia, Iran, Iraq, Russia, Kuwait—are saying, well, no, this is outside of the remit of the treaty, let's focus on the pollution side and the disposal and the recycling. But the two go hand in hand. And we have not resolved that issue yet. But when you talk with the delegates in these oil producing countries, you see that there are opportunities to sit down and talk through extended producer responsibility. How are we doing that at the national level? How can we take those experiences at the international level? So I do believe in goodwill among negotiators at the end of the day.

BELTRAN: And one of the topics that needs to be finalized in the next set of talks in Korea is the question of financing, how developing countries will get the money to carry out the commitments on plastic pollution. What possible financing methods have been discussed, and what are some points of contention?

IVANOVA: Governments have discussed a range of financing mechanisms, from a financing mechanism within the UN system that will have contributions from countries and then be disbursed to those countries that need the support, to an idea that Ghana proposed to have a fee on plastic import or plastic production that would help finance these substitutes or changes, to also getting financial contributions from the private sector.

BELTRAN: Now, observer delegations like the one you are on have only five seats available to them. Your delegation from Northeastern included an artist in one of those positions. Who was that, and why do you think it is important to have artists involved in this discussion?

Maria Ivanova is Director of the School of Public Policy and Urban Affairs and Professor of Public Policy at Northeastern University. She was part of a delegation from Northeastern at the plastic talks in Ottawa in April 2024. (Photo: Courtesy of Maria Ivanova)

IVANOVA: International negotiations are usually technical issues. There are issues about substance, whether it's on polymers, on chemicals, plastics of concern, yet their ultimate implementation depends on the change in human behavior. How do we get to that change? It's through inspiration. And I have found and am now a firm believer that the power of art is absolutely critical to inspiring people to see a different future and to come up with innovative solutions. So we included an artist, Innocent Nkurunziza, from Rwanda, the founder of the Inema Arts Center in Kigali. His works are done on renewable tree bark, tree bark that regrows—you don't have to cut the tree. It is done in a way that is sustainable, renewable, environmentally aware. What was really critical throughout the plastics negotiations is that we have seen the art of people like Benjamin Von Wong, who created the tap that was there in March, this big 30-foot tap with plastic falling out of it saying "turn off the tap" that uses plastic waste to jolt us into action. What we brought in with Innocent Nkurunziza is the other end of the art space, the vision for a plastics-free future.

BELTRAN: You know, there is still some chance that these talks could fall apart and not result in a treaty at all. What steps are being taken to make sure that the treaty does go through?

IVANOVA: As with any negotiation, there is always the possibility of having no outcome. But I have seen genuine commitment, both from member states and from the international space, the UN Environment Programme that provides the secretariat for these negotiations, to have a final outcome, to have an agreement. The fact that governments agreed to intersessional work is one example of their commitment to come out of these talks with a real international agreement on ending plastic pollution.

BELTRAN: Maria Ivanova is Director of the School of Public Policy and Urban Affairs and Professor of Public Policy at Northeastern University. Thank you so much for joining us, Maria.

IVANOVA: Thank you very much for having me.

Related links:

- Website of the United Nations Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee on Plastic Pollution

- AP News | “5 Takeaways from the Global Negotiations on a Treaty to End Plastic Pollution”

- Reuters | “Plastic Pollution Talks Make Modest Progress but Sidestep Production Curbs”

- Learn more about Maria Ivanova

[MUSIC: Lawrence Blatt, “Standing In the Rain” on Out Of the Woodwork-Eclectic Modern Compositions For the Acoustic Guitar, by Lawrence Blatt, lm Music]

Wake! Up!: Paper Wasp

Paper wasp perches on top of a flower. (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

O’NEILL: You might not think of stinging insects like wasps as particularly clever. You might not think of them at all, except to regard them with a healthy amount of fear. But Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence Mark Seth Lender once spotted a paper wasp making clever moves to get out of a building and back to the great outdoors.

Wake! Up!

Paper Wasp

One afternoon, Mark Seth Lender realizes there’s more to a paper wasp than just the sting. (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

Midafternoon and the sun shining, unable to keep my head up I lay down soon deep and dreaming.

Until the buzzing started.

BZZZZ UZ ZUZ ZUT!

Too throaty and strong and loud to be a fly. Something formidable.

BZZZZ UZ ZUT!

I open my eyes:

Paper Wasp.

Around my head –

BZZZZ ZUT!

– and to the window.

And around my head –

and to the window.

The right window.

Not the solid five-foot pane but at the small one alongside, the casement, the one that opens.

I get up. Walk over. Paper Wasp is resting on the frame not at the hinge but at the leading edge. Her wings still. Waiting.

Turn the crank -

Window pivots out –

Paper Wasp, escapes.

And everything I thought I knew of Life on Earth is upended.

O’NEILL: That’s Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender.

Related link:

Mark Seth Lender’s Website

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth