May 17, 2024

Air Date: May 17, 2024

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Eco Grief Among Scientists

View the page for this story

2023 was the hottest year on record, at 1.48 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels. That’s just below the 1.5 C increase that the UN says is the limit to avoid the worst impacts of climate change. As the summer of 2024 approaches in the Northern Hemisphere, climate scientists are raising the alarm on dangerous impacts of ongoing heat waves. Bob Berwyn from Inside Climate news joined Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill to discuss ocean heat waves and profound grief among marine scientists. (13:31)

Phantom Carbon Credits

View the page for this story

Shell’s flagship carbon capture and storage project in Canada generated millions of dollars in carbon credits based on greenhouse gas emission reductions that never took place. According to a study by Greenpeace Canada, the scheme was part of Shell’s billion-dollar Quest carbon capture project. While these phantom credits were legal from 2015 to 2021 under approved carbon tax rules, Shell’s actions raise questions about carbon capture practices in Canada’s lucrative fossil fuel industry. Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood spoke to Greenpeace Canada researcher Keith Stewart. (10:27)

From the History Books

View the page for this story

Living on Earth contributor Peter Dykstra joins Host Aynsley O’Neill for a trip back in time to the creation of the Adirondack Forest Preserve, as well to Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s signing of the Tennessee Valley Authority Act. (04:02)

Animal Self-Medication

View the page for this story

A paper published in the journal Scientific Reports describes the case study of an orangutan who treated and healed his own wound. Zoologists have long seen behaviors of self-medicating in the animal kingdom, but until now it has rarely if ever been documented in scientific literature. Michael Huffman, an ecologist who reviewed the paper joined Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran to discuss how some animals are known heal themselves. (12:10)

Nature and the Beat

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

From the chirp of a Katydid to the screech of a parrot, the sounds of nature are all around us and now can be used to help humans make music. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb reports on Beast Box, a website that allows users to create their own unique songs using catchy beats and animal calls as the instruments. (06:19)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

240517 Transcript

HOSTS: Paloma Beltran, Aynsley O’Neill

GUESTS: Bob Berwyn, Michael Huffman, Keith Stewart

REPORTERS: Bobby Bascomb, Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

O’NEILL: I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

Scientists spotted an orangutan in Indonesia making a medicinal paste out of antimicrobial leaves so he could heal a large wound on his cheek.

HUFFMAN: To make a long story short, every animal on the planet self-medicates. We have observations and, and detailed studies from everything including ants and bees, all the way up to humans who also self-medicate.

BELTRAN: Also, a Shell plant in Canada obtained millions of dollars’ worth of phony carbon credits - but it was all legal.

STEWART: Shell, however, worked a special deal where for each ton that they put in the ground, they got to sell two of those credits. And so, they could get, you know, initially $60 a ton, rather than 30. But the problem then is it just means you’re selling emissions reductions that never happened.

O’NEIL: Those stories and more this week on Living on Earth - Stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

Eco Grief Among Scientists

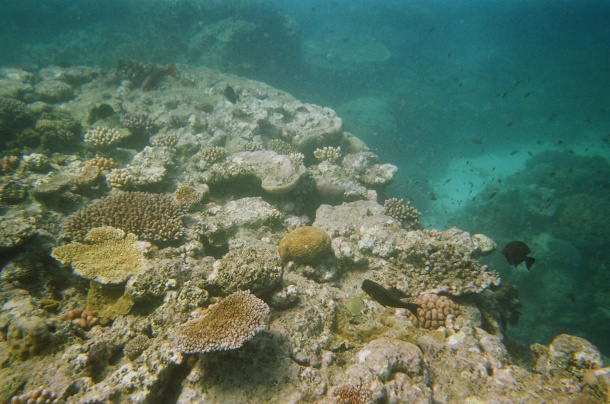

The Great Barrier Reef is the world's largest coral reef system, located in the Coral Sea off the coast of northeast Australia. (Photo: Jorge Láscar, Wikipedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

[THEME]

BELTRAN: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Paloma Beltran.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

As summer approaches in the Northern Hemisphere, climate scientists are on high alert. 2023 was the hottest year on record, at 1.48 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels. That’s just below the 1.5 Celsius increase that the UN says is the limit to avoid the worst impacts of climate change. But we’re already seeing the impacts in extreme heat, intensifying storms, and ongoing droughts. And the scientific community is not just concerned, but distraught. The Guardian conducted a poll of senior authors of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change or IPCC reports. These experts produce recommendations on how to tackle the climate crisis. And out of some 400 responses, nearly 80% are expecting a rise of at least 2.5 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels, a dangerous level of heating. Only 6% think we’ll be able to stay within the 1.5 Celsius limit. Damian Carrington is the Environment Editor of the Guardian. He spoke with several of these scientists.

CARRINGTON: The one that stuck with me was a brilliant climate scientist called Ruth Cerezo-Mota who's based in Mexico. She was talking about how she'd been at a meeting of the IPCC and started to really realize what the trajectory we’re on looks like, and what it means for people in terms of the damage to lives and livelihoods, and it kind of really shocked her. She was open with me, she said she got really depressed for quite a long time, she felt like she couldn't really do anything. But she eventually got over it and thought, actually, I've got to do my work.

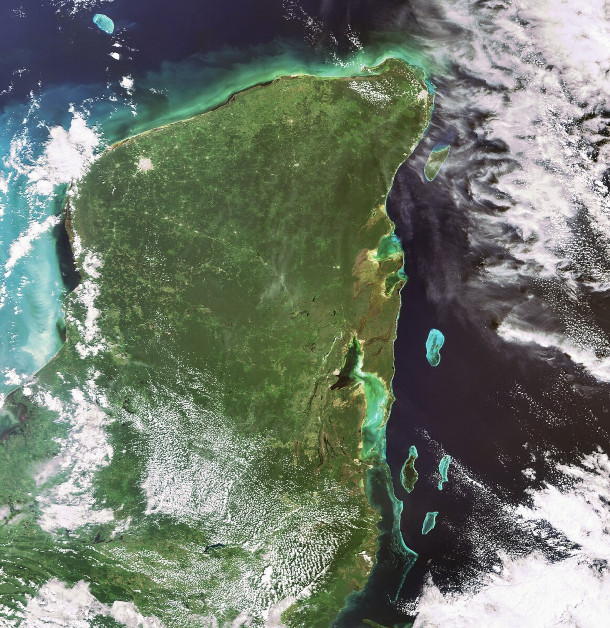

O’NEILL: Ruth Cerezo-Mota is among the scientists who predict we’ll rise above 2.5C and she is living the impacts of climate change firsthand. Her home, the Yucatan Peninsula, is a tropical, humid area where last year temperatures reached a staggering 47 degrees Celsius amid one summer heat wave. That’s around 116 degrees Fahrenheit.

The Yucatán Peninsula is a large peninsula in the Gulf of Mexico and is the homeland of climate scientist Ruth Cerezo-Mota. Last year, the Yucatan Peninsula saw temperatures reach a staggering 47 degrees Celsius amid one summer heat wave. (Photo: Wikipedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

CARRINGTON: She was saying that undoubtedly many people had died early as a result of these heat waves. And she sat there thinking, well, all the work we're doing isn't making a difference. And she was really, really upset and was saying that she continues the work so that the people who are responsible for the change cannot say they didn't know. That was her kind of motivation. They may not do anything, but they can't say they didn't know.

O’NEILL: Damian also highlighted how despite the despair, scientists say we still have time.

CARRINGTON: Ruth’s story was far from the only one. There was a scientist called Henri Waisman from France. He was saying that he had feelings of guilt about not doing enough and how that had become even greater as he had become a father relatively recently. But he said that, you know, when he feels despairing, he thinks that climate change is a slow-motion disaster. It happens bit by bit, it's not a cliff edge. And the positive bit out of that is that every 10th of a degree is worth fighting for. Every bit you stop reduces that suffering to life and livelihoods around the world.

O’NEILL: The Guardian survey also asked, “What do you see as the number one barrier to action?”

CARRINGTON: So 75% of almost the almost 400 respondents to our survey said that lack of political will was the biggest barrier to climate action and matching that when we asked them about what are the most effective actions individuals can take, most of them said voting.

O’NEILL: But still, many of the effects of climate disruption are already in progress. One place getting hit especially hard is the ocean. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the seas have absorbed more than 90 percent of the heat energy trapped by greenhouse gasses since the start of the industrial age. And just like with the IPCC scientists, marine scientists are overcome with grief and despair as their work suffers in the face of the climate crisis. For more, I’m joined now by Bob Berwyn, a journalist with our partner Inside Climate News who has been on the ocean beat for over a decade and has seen this eco-grief consistently throughout his reporting. Bob, welcome back to Living on Earth!

BERWYN: Hi, thanks for having me again, I appreciate it.

O'NEILL: So what are some of the impacts that scientists have been observing?

Jennifer Lavers is a coordinator of the marine research nonprofit Adrift Lab. She has been tracking how thousands of seabirds have starved to death during recent ocean heat waves off the coast of western Australia. (Photo: Luke Hosty)

BERWYN: Going back a few years, there have been quite a few mass die-offs of all different types of marine organisms. I think the first time that they were really well documented, going as far back as 2003 in the Mediterranean, when ocean scientists there looked at little what are called benthic organisms that live in shallow water in the seabed, mixed in with the sand and rocks, so little snails and tiny crustaceans, and documented really just an almost complete disappearance of some of these species after just one single marine heat wave. And then if you fast forward a few years, we've had heatwave conditions in the Pacific Ocean that have resulted or contributed to die-offs of marine mammals, some of which have starved to death, because the extraordinary heat in the ocean made their food supply go somewhere else, potentially, in some cases. There was a starfish die-off, which you all may have reported on a few years ago, that in some ways has been linked to very warm ocean conditions in the Pacific. And there have been mass mortalities of seabirds there as well. And other impacts include things like toxic algae blooms that in turn also affect animals. So there's been documented cases of fish and birds dying because they ate algae or crustaceans that had a toxic algae with them. And so the impacts are quite intense and quite widespread.

O'NEILL: And with these ocean heat waves, I saw you quote a statistic from a climate scientist in New Zealand. And it was some pretty scary stuff. Can you tell me a bit more about that?

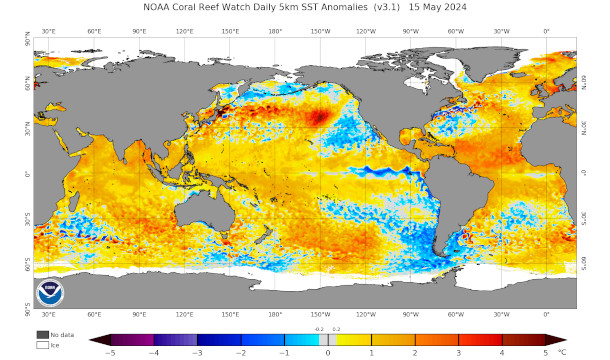

BERWYN: Fifteen years ago, people weren't talking about marine heatwaves even that much because they only happened every once in a while and affected sort of a small area. You know I'd say really, in the last 10 years, they've started to spread so far, become so big and last so long that it's really hard for almost any ocean scientist to ignore them. So just a couple of weeks ago, the scientist Ben Noll in New Zealand calculated the extent of current marine heatwave conditions, and heatwave conditions extended across about a third of the world's ocean, which is as if you had heat waves across North America, South America, Europe and Asia all at the same time. So just huge, huge expanses.

The above map shows “Sea Surface Temperature” (SST) anomalies on April 29, 2024. A positive anomaly (yellow orange or red) means the current SST is warmer than average, and a negative anomaly (blue or purple) means it is cooler than average. (Photo: NOAA Coral Reef Watch, noaa.gov, Public Domain)

O'NEILL: During your reporting, you spoke with a scientist named Jennifer Lavers who studies seabirds. What did she have to tell you?

BERWYN: Well, she's been studying around Western Australia, she has been studying seabird colonies for a few decades, and has noticed that these ocean heat waves in the last years have really started affecting these seabird colonies. And she was quite distraught about it and says that she sometimes, when she describes her work to people, is now feeling like her research is now sort of documenting the extinction of the species that she studies, the flesh-footed shearwater. And it's just one of many ocean species, birds and others, that are really being affected by these ocean heat waves.

O'NEILL: Now Bob, you've been on this beat for some time, covering the ocean. What have you seen in terms of the progression of ocean health or, you know, perhaps lack thereof?

BERWYN: Many of the scientists—Jennifer isn't the only one that I spoke with—have a real sense of grief and sadness, watching this incredible living system sort of disintegrate in real time and just sort of unseen to a lot of people, because it's just below the surface of the waters. You know, it gets in the news when there's a huge fish die-off, then there's a day or two where you have front-page pictures on websites and newspapers if there's just this huge expanse of, of dead fish. This kind of stuff has gone on in the ocean all the time, just most of the time nobody sees it, and it's really a big dying. And you know, there have been studies in the last couple of years warning that we're headed in the direction of some of the greatest mass ocean extinctions known from the fossil record. So for looking at fossils, we can tell, wow, at this time when the earth warmed really quickly 350 million years ago, more than 90% of all organisms in the ocean died. And we're not there. We're not at that point yet. But these are studies saying we are headed in that direction.

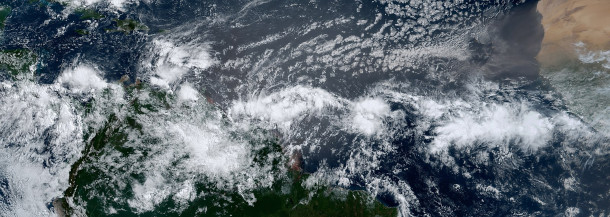

O'NEILL: Now here in the northern hemisphere, summer is right around the corner. And so we're keeping our eyes on the hurricane season that's about to start in the tropical North Atlantic. And one of the key factors in hurricane formation is, of course, sea surface temperature. What have you been hearing about the consequences of ocean heat waves on these massive storms?

The Main Development Region (MDR), located in the Atlantic Ocean, is the area where most Atlantic tropical cyclones form. Researchers tracking marine heat waves in the MDR, as the summer of 2024 is now just starting, say that record ocean heat is a key ingredient in their projections for a very active hurricane season. (Photo: Wikipedia Commons, Public Domain)

BERWYN: Good question. The part of the Atlantic that you're talking about is also called by hurricane experts the main development region, that belt of the Atlantic between Africa and the, and the Caribbean. And what some hurricane scientists have been writing about and posting about on social media is that this area is as warm now as it usually is in mid-July, when the hurricane season really starts kicking into high gear. And they're pointing out that, combined with some other factors, this heat is a warning sign that the hurricane season could be very, very active this year. And there's plenty of research from the last few years showing that the warmer the oceans are, the stronger the hurricanes can be. And that they pick up also extra moisture, because the warmer atmosphere holds more moisture. So when some of these storms come ashore, there have been climate attribution studies showing that certain hurricanes dropped a certain percentage more precipitation than they would have in a cooler climate. So all told, this extreme warmth and long lasting heat wave over that part of the Atlantic is a warning that we could be in for a really severe hurricane season. And this part of the Atlantic has been sort of record warm for months and months. And, you know, at times, it kind of calls into question whether a heat wave is really the right name anymore, because when you think of a heat wave on land, you think of an event that has a certain start date and an end date, right, like, Wow, that last summer's heat wave was a doozy, it lasted two weeks or, but these things in the ocean are going on for weeks and months, so...

O'NEILL: Bob, what was your takeaway from the scientists you spoke with here? You know, what was the common sentiment among them?

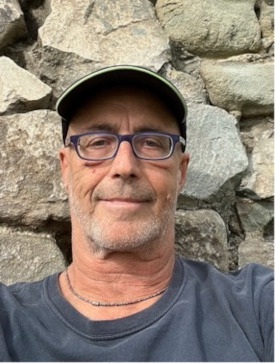

Bob Berwyn is an Austria-based reporter who covers climate science and international climate policy for InsideClimate News. (Photo: Courtesy of Bob Berwyn)

BERWYN: I think they're waving again and have been for a while, a huge red flag about the threat of global warming to marine life very, very broadly. And thus, the threat to people, because these are changes that potentially will threaten food supplies. When we talk about ocean heat waves, the projections for the tropical oceans are that by the end of the century, that they will be so warm, that there will hardly be any fish at all in the world's tropical oceans. There aren't any fish that are adapted to the temperatures that are projected for the band of tropics just north and south of the equator. And evolution doesn't happen that fast. It's not like a new species of fish can evolve within, you know, seventy years to fill that ecological niche. And so you're gonna have like a lot of people, millions of people living in tropical zones, who are going to lose an important source of food. So my main takeaway from talking to a lot of these scientists is that we need to stop global warming and hopefully slow the warming of the oceans, too, and slow this trend of more and more heat and more and more extreme heat in the oceans that is really damaging these ecosystems.

O'NEILL: Bob Berwyn is a journalist with Inside Climate News. Bob, thank you so much for joining me today.

BERWYN: You're welcome. Thanks.

Related links:

- Inside Climate News | “Increasingly Frequent Ocean Heat Waves Trigger Mass Die-Offs of Sealife, and Grief in Marine Scientists”

- The Guardian | “World’s Top Climate Scientists Expect Global Heating to Blast Past 1.5C Target”

- The Guardian | “‘The Stakes Could Not Be Higher’: World Is on Edge of Climate Abyss, UN Warns”

- The Guardian | “‘Hopeless and Broken’: Why the World’s Top Climate Scientists Are in Despair”

- Learn more about Damien Carrington

- Learn more about Ruth Cerezo-Mota:

- Learn more about Henri Waisman:

- Learn more about Jennifer Lavers:

- Learn more about Ben Noll:

[MUSIC: Keola Beamer, “E Ku’u Morning Dew” on Moe’uhane Kika - Tales From the Dream Guitar, by Keola Beamer, Dancing Cat Records]

BELTRAN: After the break, a Canadian Shell plant obtained millions of dollars worth of carbon offset credits for emissions that were never actually captured. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Keola Beamer, “E Ku’u Morning Dew” on Moe’uhane Kika - Tales From the Dream Guitar, by Keola Beamer, Dancing Cat Records]

Phantom Carbon Credits

Oil and gas fuel is Canada’s largest export, and much of that oil comes from the country’s tar sands. Shell’s Quest project was the first major carbon capture project serving Alberta’s tar sands production. (Photo: Dru Oja Jay/Howl Arts Collective, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

O’NEILL: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

The multinational petroleum giant Shell has a plant in Alberta, Canada that traded millions of dollars worth of carbon credits based on greenhouse gas emission reductions that never took place. According to a study by Greenpeace Canada, the scheme was part of Shell’s billion-dollar Quest carbon capture project from 2015 to 2021. For every ton of carbon Shell secured underground, they got credit for two tons, under the Canadian carbon tax system. While these phantom credits were surprisingly legal, Shell’s actions raise questions about carbon capture practices in Canada’s lucrative fossil fuel industry. Greenpeace Canada researchers say they publicized Shell’s actions to avoid the pitfalls of the past, as Canada formulates new carbon credit regulations going forward. Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood spoke with Keith Stewart, a senior energy strategist with Greenpeace Canada.

CURWOOD: What we're going to talk about here is perfectly legal, but from your perspective, from many people's perspectives, not exactly ethical. How fair is that to say?

STEWART: That's totally fair. I have been telling all my friends about this for a while now. And every time they hear it, they're like, that can't be legal, is it? And I'm like, oh, no, it's entirely legal. It's literally written into the law, but I don't think it's right.

CURWOOD: So, Canada has a friendly, benign international reputation. But how does that stack up when we consider fossil fuels and the challenge of climate disruption?

STEWART: Yeah, Canadians, we like to think of ourselves as Boy Scouts on the international stage, you know, helpful, not that powerful, but you know, generally nice. But when it comes to fossil fuels, we're a giant. We're—oil and gas is our largest export, we're one of the largest exporters of oil and gas in the world, we have the third largest reserve of oil in the world. And our oil is particularly high carbon in the tar sands, and just about over half of Canadian oil comes from the tar sands. So it's dirty, it's expensive, we're sending it all over the world, and most people don't know that.

Until its two-for-one deal ended, for each ton of carbon that Shell captured as part of its Quest project, it was able to obtain two tons worth of carbon credits. (Photo: Catherine Hammond, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: Talk to me, for example, about the regulations around making credits for carbon in Canada there, in the context of carbon capture.

STEWART: Canada's oil industry has been pitching carbon capture for a long time, it's kind of their silver bullet solution to pollution: Don't worry, we don't have to phase out of oil and gas. And yes, we have really high-carbon oil, but we're going to do this carbon capture, and we'll sort of like reduce carbon emissions, and it'll all be great. And the Quest project was the first one to do this in the tar sands area. And it captures just under a million tonnes per year. And right now, one of the reasons we did this report is because right now, the oil companies are under a lot of pressure to reduce emissions, because they're the biggest source. And so they're saying, okay, we can do more of this carbon capture stuff, we can capture, you know, 10 or 12 billion tonnes per year if governments give us enough money, and the government right now, the federal and provincial governments are offering to cover 62% of the costs. That's a lot. I mean, these companies are rolling in cash, they are bringing in cash like never before, they're having record-breaking profits. And yet, they're saying, you know, the governments have offered to cover the majority of costs of doing this, and the oil companies are still saying, that's not enough. We need more. And we've seen this movie before. This is exactly what happened with Quest. The provincial government offered to cover 60% of costs of this one, it's because it's, you know, the first time they're doing it, it’s a trial thing. Shell said, no, that's not good enough, we need more. And so they came up with this special deal for that project, where for each tonne that Shell sort of pumped underground, they got to sell two tonnes of carbon credits, to make extra money. And it resulted in them getting a lot more money over the life of this project. And we're sort of looking at that thinking, you know, this is not a great idea. And we're partially raising this now because we want to make sure it doesn't happen again because right now they're negotiating over this new deal. We're bringing in regulations to limit greenhouse gas emissions from the oil sector, they're fighting back hard against them. And we want to make sure there aren't these kinds of loopholes put into the new rules that are being proposed right now. So let's look at what happened last time and make sure we don't make the same mistakes.

CURWOOD: They pumped this carbon into the ground, what would they do to get carbon credits? What would they get paid? What was this all worth?

According to Keith Stewart, the pricing system used by Shell’s Quest project leads to more pollution since it allows the company to profit from emissions reductions that never happened, incentivizing more emissions. (Photo: Roy Luck, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

STEWART: In Canada, we actually have a carbon pricing system. So companies have to pay for their emissions. It's a very complicated system, but it's basically, on some of their emissions, they pay a certain amount per tonne, it started at $30 per tonne, and, you know, went up to $50 per tonne. So the idea with this project is for each tonne that they pump underground, Shell or whoever they sell the credits to doesn't have to pay that $30 a tonne. So it's worth $30 a tonne to them. And that's how they get revenue for doing this. And Shell, however, worked a special deal where for each tonne that they put underground, they got to sell two of those credits. And so they could get initially $60 a tonne, rather than 30. But the problem then is it just means you're selling emissions reductions that never happened, which means we're getting more emissions put out into the air, because otherwise it would have had to been reduced. And so it's kind of countering the actual potential good thing that comes from this if the carbon stays underground forever, by letting other companies pollute more.

CURWOOD: Those were the regulations then--what about now?

STEWART: This two-for-one deal was ended in the end of 2022. And they never said exactly why they're end—it’s partially that price of carbon emissions has been going up. So it's currently like $85 a tonne. So they no longer need that extra money. But it was also, I suspect, because the federal government kind of forced Alberta to change their system. The federal government had won a Supreme Court case saying they were allowed to do industrial carbon pricing. The federal government said, okay, Alberta, you've got to meet our minimum standards. Previously Alberta—because Alberta challenged it to the Supreme Court and said, this is illegal, the federal government can't make us do this. Now they submitted, okay, they're making us do it. So I think what happened was the federal government kind of said, okay, no more of this two-for-one stuff.

CURWOOD: What are the numbers that we're talking about here? How much carbon was sequestered here, and how many carbon credits were issued under this Quest program by Shell?

Canada has a complex carbon pricing system. Taxpayers paid much of the cost of the Quest carbon capture system through subsidy programs. (Photo: Karim Rezk, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

STEWART: Well, as of the end of 2022, Shell had buried 5.7 million tonnes of emissions, and had got those credits for those 5.7 million tonnes, and then an additional 5.7 million tonnes through this two-for-one deal. And the sale of those put together was worth $400 million. So they got—well, 406. So they got $203 million for selling those, you know, additional, what we would call phantom credits, for reductions that didn't really happen.

CURWOOD: So what did this project then cost Canadian taxpayers?

STEWART: Taxpayers paid about $750 million in direct subsidies, and then another $200 million in what we would call these phantom credits. So in the end, when you add those two together, it was 93% of the total costs of the project were basically paid through these subsidy programs. And in the end, Shell actually made an 11% profit on it so far, but they only managed to get this positive return by selling those extra credits. And that's why they sort of worked this deal, but, you know, we would say these are some of the richest companies in the world are these big oil companies. The average Canadian taxpayer shouldn't be paying 93% of their costs to clean up their pollution, we have this principle called polluter pay, the polluter should actually pay to reduce, not be putting out their hand to the taxpayer for that money.

CURWOOD: What prompted you to take a look at these carbon credits in the Quest program?

STEWART: We started this investigation because we know there's going to be some kind of credit trading system in the new cap system that's being brought in. And we're trying to sort of say, okay, what exactly happened with this the last time, and make sure that these kinds of backroom deals, kind of like, you know, you could find out about them, if you know exactly where to look, we want to make sure that those aren't happening again. And that's—we’re going to pull these negotiations out of sort of back rooms and sort of quiet negotiations into the public, so the public really knows what's being done on their behalf by decision makers. You've got to watch closely what's happening because oil and gas has some of the best lobbyists in the country, some of the best lobbyists in the world, frankly, and they're going to try and get the best deal possible. And we want to make sure that we're watching from the other side, to protect planet and pocketbooks of the average person. So we took a look at the Quest program because in many ways it's pointed to as the poster child for how to do this. It's the example that's always used as, oh, here's this great program in Canada that's sort of capturing all these emissions. And we said, okay, well, let's look under the hood and see exactly how good this is. And when you see something like these double credits, I mean, completely undermines the integrity of the whole system.

Keith Stewart is a senior energy strategist with Greenpeace Canada. (Photo: Courtesy of Keith Stewart)

CURWOOD: Your research shows that there were some very clever moves made by the oil and gas industry around these regulations when it came to accounting for these carbon credits. What about the technology itself? How well does it really work?

STEWART: There's two kind of issues with carbon capture. One are just the technical thing: is it going to work over the long term? What we've seen is a lot of the projects have been built haven't worked very well. Quest works better than most to be honest. This kind of technology works well for certain types of applications, where there—you’re really concentrated stream of carbon dioxide. It doesn't work as well for more diffuse ones. A bunch of times when they tried to put it in a coal plant, it really hasn't worked well. It's application specific as to how well it works. But then there's all the issue of, once you put this stuff under the ground, will it stay there? And the oil industry assures us, oh, no, it'll stay down there forever. And like, well, we've got a lot of leaking oil and gas old wells that were supposedly plugged here in Canada.

CURWOOD: Keith, how do you feel about this whole thing?

STEWART: We're at a really critical time in the fight against climate change. And I just think it's so important that we go all in on real solutions. And part of this is going to have to be fighting back against the oil industry lobbyists who want us keep us sort of stuck in the energy system of the past. And so I think we undertake this kind of research because we want to, like, pull back the curtain, let people see what's happening behind the scenes, these types of behind-the-scene negotiations. And I think when people see that, they're gonna, like, push for those real solutions. And I think it's, you know, we need people to get involved, because we really don't have any time to waste on getting action on real climate solutions now.

BELTRAN: That’s Keith Stewart of Greenpeace Canada, speaking with Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood. Shell has said in press reports including the Financial Times that their carbon capture plan, quote, “played an important role in helping to decarbonize industry and sectors where emissions cannot be avoided.”

Related links:

- Read the Greenpeace report on Shell’s Quest carbon capture and storage project:

- Financial Times| “Shell Plant Reported Millions of ‘Phantom’ Carbon Credits”

- Shell’s blog post responding to the Financial Times article:

- Explanation of carbon pricing from the government of Canada:

[MUSIC: “O Canada” – Canada’s National Anthem, performed by the National Anthems Channel ensemble, Words by Robert Stanley Weir/Music by Calixa Lavallee, on Youtube’s national anthems channel]

From the History Books

The mesmerizing high peaks of the Adirondack Preserve. (Photo: John Munt, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

O’NEILL: It’s the time in our show where we get Peter Dykstra on the line from Atlanta, Georgia. He’s the Living on Earth contributor who’s gonna bring us a couple of stories from the history books. Hey, Peter, whatcha got for me this week?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Aynsley, we're gonna go way back to 1885, specifically, May 15, 1885, when the state legislature and the governor of the state of New York created the Adirondack Forest Preserve, a huge area of 681,000 acres. And they did it out of enlightened self interest. They were concerned that New York City's water supply would be threatened if the Adirondacks were continued to be clear cut, so they set this huge area of state off limits.

O'NEILL: Well, providing New York City clean drinking water is so important. Not only do they provide something like 1 billion gallons of clean water to all the city's residents every single day, but New Yorkers will also say it's the reason why their pizza and bagels are so good. And Peter, with you and me both from northern New Jersey, we get to reap some of those benefits.

DYKSTRA: Oh, no, absolutely. We both grew up in the New York area. And without that high quality H2O in New York City, it would be "fuhgeddaboudit" for one of the largest cities in the world.

O'NEILL: Alright, Peter. But the tangent aside, tell me more about the Adirondacks.

DYKSTRA: Not only was there development pressure to build new farms, new large resort hotels, but Adirondack Park remains largely protected today, despite all those development pressures. And despite the damage done in the past century from acid rain. But there were so many other preservation areas since Adirondack Park being arguably the first in the U.S.: the Grand Canyon, Yosemite, the Cape Cod National Seashore, and many others. There was initially huge opposition to setting these areas off limits. That opposition was conquered. The Adirondack Forest Preserve led the way.

O'NEILL: Mmhmm. Alright, Peter, what else do you have for me?

As the Tennessee Valley Authority's inaugural venture into flood control and hydroelectric power production, the Norris Dam was constructed between 1933 to 1936 spanning from the Clinch River from Campbell County to Anderson County in Tennessee. (Photo: Warren LeMay, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Two months after his inauguration, Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed the Tennessee Valley Authority Act. President Roosevelt helped create the TVA largely to make the Tennessee River navigable, and also to bring electricity and jobs to the impoverished region. TVA becomes one of the nation's largest operators of coal and nuclear power plants. So it hasn't always held an environmental value at the highest level.

O'NEILL: And Peter, the TVA is still kicking today, right?

DYKSTRA: The TVA is still there, it's still a political behemoth throughout the region of all of the states in the Southeast except for Florida. And that political powerhouse is not always working in conjunction with environmental values. You may remember about 10 years ago, in Kingston, Tennessee, there was a huge coal ash spill that polluted a large section of the Tennessee River tributary. The TVA has always needed to get a little extra push in working toward keeping the Tennessee River and its environments clean. It hopefully is going to do a better job in the future.

The aftermath of the Tennessee Valley Authority's Kingston Fossil Plant retention pond breach near Harriman, Tennessee, revealing a vista of the ash spill across an inlet that flows into the Emory River. The scene, approximately one mile downstream from the failure site, showcases the environmental impact in the southeastern United States. (Photo: Brian Stansberry, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 3.0)

O'NEILL: Alright, Peter, well thank you for bringing us these stories. Peter Dykstra is a Living on Earth contributor, and we will talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Aynsley, thanks a lot. We'll talk to you soon.

O'NEILL: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth website. That's L-O-E dot O-R-G.

Related links:

- Plan your visit to the Adirondacks

- More on the history of the Tennessee Valley Authority

[MUSIC: Doc and Merle Watson, “Home Sweet Home” on Home Sweet Home, Traditional American/arr. Doc Watson, Sugar Hill Records]

BELTRAN: If you enjoy the stories you hear from Living on Earth, please consider signing up for our newsletter. You’ll never miss a show, and you’ll have special access to show highlights, notes from our staff, and advance information about upcoming live virtual events. The Living on Earth newsletter is sent to your inbox weekly. Don’t miss out! Subscribe at the Living on Earth website, L-O-E dot org. That's L-O-E dot O-R-G.

[MUSIC: Doc and Merle Watson, “Home Sweet Home” on Home Sweet Home, Traditional American/arr. Doc Watson, Sugar Hill Records]

O’NEILL: Coming up, researchers studied a wild orangutan making his own medicine to heal an injury. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Oscar Pettiford/Jan Johansson/Stan Getz, “I Remember Clifford” on Stunt Records Compilation Vol. 25, by B. Golson, Sundance Music]

Animal Self-Medication

Sumatran orangutans are an endangered species native to Indonesia. (Photo: cuatrok77, Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

O’NEILL: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

Much of humanity’s medicine has its roots in the natural world around us. Think about asprin, whose main ingredient can also be found in plants like willow and myrtle. Or for something a little stronger, opiates, which are synthesized from the flowers of the poppy plant. But humans aren’t the only creatures who have used plant medicine: zoologists have long seen behaviors of self-medicating in the animal kingdom. And recently, a paper was published in the journal Scientific Reports that describes the case study of an orangutan who healed his own wound. Rakus is a male, Sumatran orangutan living in Indonesia. After he sustained an injury to his face, Rakus chewed up the leaves of a woody vine called Akar Kuning. He then applied both the juice and the leaves of the plant to his face. Within five days, the wound closed. Here to talk to us about this discovery is Michael Huffman, an ecologist who has spent his career studying the ways animals self-medicate. While he isn’t an author of the paper, he was one of the reviewers prior to publication. Michael Huffman, welcome to Living on Earth!

HUFFMAN: Thanks. Nice to be here.

BELTRAN: What makes this discovery new and exciting?

HUFFMAN: Well, it's the first detailed observation of an animal taking a plant and putting it onto a wound. And that wound apparently healed in a relatively good period of time. But the fact that the male put a plant with medicinal properties on a wound, very concertedly, it couldn't be mistaken as just an accident, is very interesting. There have been many reports unpublished and unscientific about this type of thing in other animal species. So to have this detailed observation and have it published is very important, because it'll wake up scientists in the field to keep an eye on this kind of behavior, because there are previous examples of something like this happening in other species, but we didn't have the details that this paper has provided.

BELTRAN: So the plant that the orangutan named Rakus used to self-medicate is called Akar Kuning. What do we know about this plant?

HUFFMAN: The scientific name, the Latin name is Fibraurea tinctoria. And it seems to be widely used in Asia, Southeast Asia as medicine. It has anti-inflammatory properties. It has antimicrobial, probably antibiotic properties, as well, and people use it widely. Another interesting thing, the researchers in this team and those from other groups who have been working at this site for a very long time, had never seen that behavior before, and Rakus the male came in from an outside population as male orangutans do, they lead the group that they're born into, and they, they tend to travel around fairly solitarily and try and establish a territory, so he may be introducing a new behavior into this population that will allow these orangutan, if the behavior is transmitted to others, to treat wounds, which can be a serious problem, especially in the tropics. Wounds are hard to heal. They tend to ulcerate and early treatment and keeping it clean is very important. Animals have an amazing way of healing themselves to begin with, they have a strong immune system. But as we know from other types of self-medication, they also need plants and things to help that process along.

BELTRAN: And from what I understand primates are not the only animals who self-medicate. Tell us more about that.

HUFFMAN: To make a long story short, every animal on the planet self-medicates. We have observations and detailed studies from everything, including ants and bees, all the way up to humans who also self-medicate. Before modern medicine, all the treatments were happening in the home. People were going out into the forest finding a plant that they had learned from their elders were effective in treating a number of different symptoms. So every species of animal on the planet gets sick, are affected by parasites or microbes or some other type of disease. We have accidents. We fall. We get cut. So every species on the planet self-medicates.

BELTRAN: If such a broad range of species do this, then they probably have many different approaches. What are some other ways that animals self-medicate?

HUFFMAN: The patterns seem to be very similar across different species. Two of the modes that I have been working on in various different species, not all primates, is that in the normal diet, they include things that we would consider things like, spices, chilies, gingers, things like that. Onions even have antibacterial properties. So they keep the food from spoiling, they keep down the microorganisms that can give us an upset stomach, for example. Another example that I found really, really interesting is called leaf swallowing. And plants have a self-defense mechanism to prevent animals from over eating their plant bodies. And so they transfer toxic compounds to the leaves or they'll set up barriers like very small hairs and things that are very hard to digest. And if an animal eats too many of these leaves, then it gets indigestion. So they tend to avoid certain leaves of certain species because of those properties that the plant uses. But some animals have found a way to use that to their benefit, and they'll fold and swallow these leaves that are hard to digest. And what that does is reduces the time that it takes for food to pass through the system. And normally it's up to 24 hours, 30 hours, maybe but what a number of different species, African great apes included, will do is fold and swallow leaves, reducing that transit time to six hours, and they're expelling the parasites in their intestinal tract. So they have a physical means of purging themselves of parasites. So it's a cool way of keeping the system clean. And we have examples of this in birds, in bears, in several primate species. It's really an interesting way of controlling parasites.

Dr. Michael Huffman has spent the majority of his career studying self-medication in animals. (Photo: Courtesy of Michael Huffman)

BELTRAN: Professor, you've spent most of your career studying this topic. What got you interested in the subject?

HUFFMAN: I first stumbled upon self-medication in animals following chimpanzees in Tanzania in the Mahalia mountains. It was not my research topic. But I was always interested in medicinal plants and how traditional cultures around the world use those plants. And I had the good fortune of working with Mohamedi Seifu Kalunde. He was one of the staff in our research project that had been ongoing since 1965. And I started studying chimps in 1985. And I would often walk with him in the forest. And when we couldn't find the chimps, he would teach me about plants that his family had learned about and used to treat other people in the village. We worked together for probably close to 20 years. And it was the second year into my research there and working with him that we came across a chimpanzee named Chausiku. She did something very interesting. I hadn't seen chimps eat a certain plant until that day, and it was Chausiku, who was doing it. And I asked Mohamedi, what's the name of the plant and he told me, it's Majonso. And I had never heard of that name. Tell me more about the plant. But I was interested in what, how she was going to eat it. So I was just watching as Chausiku took this plant and she peeled off the bark and started chewing on the pit. Very, very fresh, like celery. So she was chewing, and then she sucked out the juice, but spit out everything else. Mohamedi breaks in and says, "Yeah, it's very, very bitter. I don't know why chimpanzees would want to eat this very bitter plant. We use it as medicine." And I began to remember that earlier that day, she wasn't well, and she climbed up a tree, built a nest and went to sleep. But she left her young infant Chopin just running around doing his thing. First thing that Chausiku did was to go to this plant Vernonia amygdalina. So we were able to understand during the observations of two days, that she was very sick the first day, really not well the next morning, but by the next noon time, her behavior changed completely. Her appetite came back. Her strength came back. So just those two days was the beginning of a 35-year study on how animals self-medicate, and it continues today.

Nature is so cool! And we have no idea!

— 360 on History (@360onHistory) May 12, 2024

Rakus the orangutan patched a wound on his face up with a #medicinalplant - a first ever recorded instance of an animal self-medicating! #NatureIsAmazing #Intelligence #nature #animals #medicine https://t.co/OTnHv3g0Tg

BELTRAN: Although science has only somewhat recently acknowledged self-medicating animals, indigenous communities have known about this phenomenon for 1000s of years. Can you talk a little bit about that?

HUFFMAN: As I mentioned before, with working with Mohamedi, we worked for about 20 years together, and it was only around the seventh, eighth or ninth year of our collaboration deep into studying animal self medication in chimps that one day when the chimps were way, way up in the mountains, we were waiting for them to come down. And then he said, "I have a story for you about a plant that my grandfather discovered by watching a sick porcupine." And he went to tell me about how his, his grandfather, Babu Kalunde, discovered a very strong antibiotic by watching a porcupine dig up the roots and treat itself for bloody stools. And I said, "Well, that, that's amazing." And he says, "Yeah. And we have other examples." And I go, "What? You mean, your family and your tribe know that animals self-medicate? They've been aware of this for a long time?" "Oh, yeah, we have many examples like this." So I got really interested, and I started looking at the literature from around the world. And it turns out that almost every society that I've been able to read about or talk with people from that culture, there is at least one plant that they have learned from animals.

Dr. Huffman worked closely with Mohamedi Seifu Kalunde in Tanzania to learn more about the medicinal properties of native plants. (Photo: Courtesy of Michael Huffman)

BELTRAN: And what are your hopes for the future of this research?

HUFFMAN: Well, I hope more and more people will come on board and start looking carefully at their study subjects. Look at new species, we know very little about how animals in the ocean self-medicate. There's a lot of plants in the ocean that have toxic properties. Just like plants on land, they produce these things to protect themselves. But I'm sure that, that animals have also learned that those substances can be of benefit. So that may be one of our final frontiers, as it were, to go to the ocean and see how animals in the sea are dealing with diseases. But there's still so much on land in all the different habitats that animals live in that we really need to look at more. And I think in the end, the more we appreciate how animals exist in their environment, how they've acquired all of this knowledge and how it's maintained within these different societies of animals, different cultures of animals, we'll come to appreciate them more and take better care of the planet. I don't know who said this, but it is so true. Nature doesn't need us. We need nature. So I think we have to take better care of the nature around us and pay a little bit more respect to the animals who are living there.

Although it is likely that many of the animal species on the planet self-medicate, scientists most often identify the behavior in primates, like chimpanzees. (Photo: Bernard Dupont, Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

BELTRAN: Dr. Michael Huffman is a visiting professor at the Institute of Tropical Medicine at Nagasaki University. Thank you for joining us.

HUFFMAN: Thank you.

Related links:

- Read the original study about Rakus

- Learn about Michael Huffman’s work with chimpanzees

[CALLS OF A BORNEO]

Nature and the Beat

A Beast Box Orangutan and a Bornean Orangutan. (Image: Russell Watkins/Shutterstock and Beast Box)

O’NEILL: Let’s listen now to some of Rakus the Sumatran orangutan’s smaller primate cousins, gibbons, whose howling calls can travel up to two miles across the dense rainforests of Borneo. Many animals make some sort of sound to find a mate, warn of predators, or claim and defend their territory. And now their sounds are being used to create music. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb reported this story in 2018.

[SFX KATYDID]

BASCOMB: For many of us, the staccato notes of a katydid might conjure up memories of a warm summer night, but for Ben Mirin a katydid’s chirp is music.

MIRIN: I hear music in everything.

BASCOMB: Ben calls himself a Wildlife DJ. He travels the world as a National Geographic explorer to record animal sounds. And with help from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ben created a website called Beast Box where users can layer animal sounds over a beat to create their own compositions.

MIRIN: I’m just a messenger for the intricately tuned voices of the natural world. And the fact that nature is always singing is something that is really exciting to me and I hope can create similar excitement and joy others.

BASCOMB: To make a song, users open the website and then choose one of 7 beat tracks that Mirin created himself. You can choose, say, Great Barrier Reef beat…

[SOUND – GREAT BARRIER REEF BEAT]

BASCOMB: Or Sonoran Desert Beat…

[SONORAN DESERT BEAT IN CLEAR]

A Beast Box Cicada. (Image: Beast Box)

BASCOMB: Then select an animal sound. There are 30 of them. You can add as many as five at a time to create a song. So, let’s say you choose a coyote….

[CALLS OF COYOTE IN CLEAR OVER BEAT]

BASCOMB: Then an eastern whip-poor-will …

[MUSIC ADDING WHIP-POOR-WILL]

BASCOMB: A parrot fish …

[MUSIC ADDING PARROT FISH]

BASCOMB: A Hadada Ibis …

[MUSIC WITH ADDED IBIS OVER BEAT]

BASCOMB: And lastly a Blue Wildebeest.

[MUSIC WITH ADDED WILDEBEEST OVER BEAT]

BASCOMB: Put them all together and your song is complete.

[MUSIC PLAYS, THEN FADES TO BED]

BASCOMB: On the website there is a paragraph description of each animal and an explanation of their habitat. Each time a user chooses an animal musician, a graphic of that creature pops up on the screen and dances to the beat. For instance, there’s an orangutan in a red leather jacket and matching sunglasses.

[CALLS OF ORANGUTAN WITH BEAT BACKING]

BASCOMB: And a tropical Boubou wears a gold chain and a red cap.

[CALLS OF BOUBOU WITH BEATS]

BASCOMB: Mirin hopes beast box will be fun for anyone, but the graphics and the genre of music are geared towards kids like 12 year old Orion Brown. Orion says he likes playing with the website.

A Bornean Gibbon. (Image: Beast Box)

BROWN: I think it’s pretty cool. It’s a way to get a good education but also have some fun.

BASCOMB: For an additional challenge, users can try to put all of the animals from the same ecosystem together with the beat designed for that environment – it’s called Beast Mode. Orion chooses the Madagascar Rainforest.

[BEATS OF MADAGASCAR RAINFOREST, PLAYS AS BED]

BROWN: The first animal in that ecosystem is the Indri.

BASCOMB: Neither of us know what an Indri is. So Orion reads the description -- turns out they’re lemurs.

BROWN: A small group of Indri wake up in the treetops and begin their morning shout outs. Indri are large for lemurs, with booming voices amplified by enlarged throat pouches.

[INDRI CALLS ADDED]

BASCOMB: Alright, what’s next in the Madagascar rainforest?

BROWN: The next one is the Lesser Vassa Parrot.

[PARROT CALLS ADDED]

A Blue Wildebeest. (Image: Beast Box)

BASCOMB: He finishes up with the Madagascar Long Eared Owl, the Red Fronted Coua, and the Souimanga Sunbird.

[“BEAST MODE” THEN SONG PLAYS AND FADES TO BED]

BASCOMB: So what do you think of the song you made?

BROWN: Um. I think when you mash them up with all the ecosystems together, it sounds better, almost like it’s sort of made for the beat.

BASCOMB: So, you mean when you have all of the same ecosystem, like all of the desert or the rainforest or so together?

BROWN: Yeah.

BASCOMB: Do you think that maybe, they lived together in the same forest and making music together, it comes kind of naturally. What do you think of that idea?

ORION: I think that would be a possibility and if so, that would be super cool.

BASCOMB: Ben Mirin says that Orion is on to something, thinking that the different animal voices complement each other.

MIRIN: Yeah, I would agree with his observation. Animal voices have evolved over millions of years to occupy different acoustic niches in an ecosystem so they don’t compete with one another.

BASCOMB: Making yourself heard is critical to surviving in nature. That’s how whales find mates across the ocean and coyotes defend their territory in the desert. Animals living in the same environment are already tuned to work well together so everyone can be heard. And Mirin is excited about tapping into that existing symphony of sounds.

MIRIN: As a producer that means my instruments are already mixed. So instead of being a solo musician I get to be a messenger for the finely tuned orchestras of the natural world.

National Geographic Explorer and wildlife DJ Ben Mirin. (Photo: Drew Fulton)

BASCOMB: Mirin says what he wants is for Beast Box to help people learn about nature and create a connection with the natural world.

MIRIN: At the end of the day understanding and connecting with nature is critical to falling in love with it and we can’t save what we don’t love. So, I would hope that this opens a pathway for you to find your own sense of connection and love for nature so that you can be inspired to protect it because this is a collective future we all share.

O’NEILL: Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb reporting. And there’s much more about Ben Mirin and his Beast Box at our website, L-O-E dot O-R-G.

Related links:

- Beast Box

- Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- About Ben Mirin

[MUSIC: Izabella Effenberg, “Crystal Silence 1” on Crystal Silence - Music for Array Mbira, by Izabella Effenberg, Unit (Membran)]

BELTRAN: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Shanzay Asif, Josh Croom, Jenni Doering, Karen Elterman, Swayam Gagneja, Sommer Heyman, Mattie Hibbs, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Allison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and YouTube Music, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram @livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments at L-O-E dot org. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer.

I’m Paloma Beltran.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth