May 24, 2024

Air Date: May 24, 2024

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Vermont's "Climate Superfund" Bill

View the page for this story

Facing costly climate impacts such as the billion-dollar flood disaster of July 2023, Vermont is seeking to make fossil fuel companies pay. Vermont Law and Graduate School Emeritus Professor Pat Parenteau joins Host Paloma Beltran to discuss the state’s “Climate Superfund” bill and its potential influence. (11:34)

The "Little Sea" with a Big Champion

View the page for this story

The Mar Menor or “little sea” lagoon on the coast of Spain faces impacts from mining, agriculture, and a booming tourist industry. Teresa Vicente is a professor of philosophy of law at the University of Murcia who helped pass a 2022 law granting the lagoon legal personhood to give it greater protection. She recently received the 2024 Goldman Environmental Prize for Europe and joins Host Aynsley O’Neill to share how she led a grassroots movement to protect this beloved lagoon. (06:07)

Uncovering the Truth About Beef and Deforestation

View the page for this story

The Brazilian cattle industry has led to massive land clearing in the Amazon rainforest. Investigative journalist Marcel Gomes set out to uncover which companies were involved and documented a direct link between the meatpacking company JBS and illegal deforestation in Brazil. He received the 2024 Goldman Environmental Prize for Central and South America and joins Host Paloma Beltran to talk about the need for more transparency about where beef comes from and better cattle grazing practices. (08:48)

From the History Books

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Living on Earth Contributor Peter Dykstra and Host Aynsley O’Neill look back to the Lacey Act of 1900, one of the first wildlife protection laws. They also note the founding of the Sierra Club and discuss how the conservation legacy of its first president John Muir has been complicated by his racist views on Native and African Americans. (03:13)

The Drowning South

/ Chris MooneyView the page for this story

Sea levels are rising everywhere due to climate change but not equally, and a recent Washington Post series called “The Drowning South” documents how the US southeast is experiencing an especially rapid rise. Journalist Chris Mooney joins Host Paloma Beltran to talk about how communities near Mobile, Alabama and St. Tammany Parish, Louisiana are being affected. (09:27)

Sounds of Soil

View the page for this story

Sounds like the overlapping songs of birds can speak volumes about the biodiversity in an ecosystem, and now scientists are looking to use the tiny sounds made by earthworms, ants, and voles to study the health of soils. Ecologist Carlos Abrahams joins Host Aynsley O’Neill to explain why more varied sounds appear to indicate healthier soils, and the potential applications of listening for these sounds in the earth. (07:44)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOSTS: Paloma Beltran, Aynsley O’Neill

GUESTS: Carlos Abrahams, Marcel Gomes, Chris Mooney, Pat Parenteau, Teresa Vicente

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

O’NEILL: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

O’NEILL: I’m Aynsley O’Neill

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

Vermont wants fossil fuel companies to finance climate adaptation with the Climate Superfund Act.

PARENTEAU: What Vermont is doing, and what I think many other states are going to be doing is looking to the oil companies to pay their fair share for the damage that's being done. I think there's a legal and a moral case to be made for holding companies responsible, and we'll now see how fast that can happen.

O’NEILL: Also, why researchers are putting their ears to the ground to listen for earthworms, ants, and voles.

ABRAHAMS: Where you have diverse sounds, that is a good indicator of good environmental health, good land management practice, and lots of fauna in the soil. So, a biodiverse soil fauna.

O’NEILL: That and more this week on Living on Earth - stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Vermont's "Climate Superfund" Bill

A flood in July 2023 left Vermont’s capital Montpelier underwater for weeks, causing more than $1 billion in damages. (Photo: The National Guard, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

O’NEILL: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

Vermont’s House and Senate have approved a bill that would make fossil fuel companies financially liable for their carbon pollution and its role in the climate crisis. Lawmakers pointed to consequences of these carbon emissions, like the flood in July of 2023 that put parts of the state capital underwater for weeks and caused over a billion dollars in damage. The bipartisan bill is known as the Climate Superfund Act because it demands that fossil fuel companies cover at least part of the growing costs of climate change. Similar bills are being considered in New York, Massachusetts and Maryland, but Vermont is the first state to pass this kind of legislation. The bill passed with a supermajority enough to override a potential veto. It is now headed to Governor Phil Scott’s desk. Pat Parenteau, former EPA regional counsel and emeritus professor at Vermont Law and Graduate School, joins us now to discuss. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Pat!

PARENTEAU: Thanks, Paloma. Good to be with you.

BELTRAN: So Pat, what is the Climate Superfund law in Vermont? And what does it say?

PARENTEAU: It's basically asking fossil fuel companies to contribute to the costs for adaptation to the unavoidable impacts of climate change, including protection of homes and businesses threatened by flooding, building resilience in floodplains by moving structures out of harm's way, investing in wetland protection and natural systems that absorb carbon emissions and provide for more resilience to extreme weather events. So it's a new approach, and Vermont is the first state in the country to try it.

BELTRAN: And how is this law different from the climate deception lawsuits like the one we've seen filed in the state of Hawaii?

PARENTEAU: So this law doesn't depend on proof of deception, or false advertising, or the campaign to sow doubt about climate change that the companies are accused of in over 30 lawsuits actually, across the country. The companies are liable by virtue of what they do. It's not that they've committed anything wrong, necessarily, it's just "polluter pays" is the concept here. So the fact that your product creates carbon pollution, which is driving climate change, that's enough to make you liable, in the same way, or at least a similar way, to how the Superfund law at the federal level makes you responsible for contamination of soil and groundwater as a result of your activities at a site. You may have generated chemical waste that wound up at the site, you may own the site, you may operate a landfill or other facility that's become contaminated. And the Superfund law says, by virtue of the fact that you own or operate or generated waste, you're liable. In the same way, this law is saying the fact that you extract and burn fossil fuels is enough to make you liable for the damage that results from that.

Vermont’s Climate Superfund Act demands that fossil fuel companies contribute to paying for climate change adaptation and mitigation in the state. (Photo: Svetoslav Nikolov, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

BELTRAN: And we're talking about money here, Pat. So how might the state of Vermont go about calculating which companies owe what? What are the possible methods they could use here?

PARENTEAU: Right, that is the big question. The formula that the law is using—and the state treasurer will have to flesh this out—is to say, what is the individual company's share in the global emissions? The law also directs the state to use the Environmental Protection Agency's greenhouse gas inventory as a starting point. And the greenhouse gas inventory has something called emission factors. For example, for the big oil companies, they can disaggregate among the different companies what their emissions factor is for the amount of oil and gas they're producing. So it's going to be a proportionate share, based on what the individual company's emissions are, that's going to be the basic formula.

BELTRAN: That's a big job, to calculate all of that.

PARENTEAU: Yes. And then from there, you have to say, well, what percentage of harm is the emissions doing on top of the natural cycle of flooding, for example, just sticking with the flooding example. There are other impacts, of course, of climate change in Vermont. There's impacts on the ski industry, there's impacts on the sugar making industry, our famous syrup, for example, there's lots of different impacts. But just in terms of flooding, you know, what you have to calculate is by how much has climate change increased the damage from flooding that normally would occur in Vermont? The flooding of Montpelier was definitely much greater than any prior flood we'd ever had. But you have to calculate how much worse was it as a result of the emissions from these companies? That's another tricky calculation.

Vermont’s ski industry has also been affected by climate change and could potentially require assistance from a superfund. (Robbie Shade, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BELTRAN: And how are these oil companies expected to respond?

PARENTEAU: Well, we know that the oil companies are not going to start sending checks to Vermont. The oil companies have been fighting tooth and nail against all of the other lawsuits that have been brought against them. And we can expect the same thing here. The companies have a choice to make. They can either file what's called a preemptive strike and challenge the law on constitutional grounds, for example, they may argue that this is a violation of due process to make them liable, when they haven't, quote, done anything wrong. They're producing a valuable product that people are still buying, of course, to put into their automobiles, to heat their homes and so forth. And so they're gonna say, you're making us liable for engaging in economic activity that's lawful? How can you do that? That's not constitutional. Similar arguments were made against Superfund, the federal law. And it took a while, took several years for those arguments to finally be resolved in the court. Ultimately, it went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. And in the Superfund case, there is precedent for establishing liability for the damage that legal activity, but nevertheless, is causing damage. But whether that precedent under Superfund extends to the climate liability context, that's going to be a major issue, that's a novel issue. So one option for the companies might be to challenge the law on its face. The other option would be to wait until Vermont actually sends them a bill in effect, right, a demand for payment, and then not pay, in which case Vermont would have to initiate a lawsuit to collect the money that they've demanded. So either way, this issue is sure to end up in court. And it will take, of course, the usual long time for it to finally get settled.

BELTRAN: And, Pat, what are some of the concerns raised by opponents of the law other than these oil companies?

Some opponents of the bill argue that Vermont should use state resources to directly help affected communities, rather than pay for years of litigation with fossil fuel companies. (Photo: The National Guard, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

PARENTEAU: The opposition to passage of the law came from those who are concerned that Vermont is too small a state to take on these major—multinational, really—corporations, that, as we've just discussed, this isn't going to just happen without litigation. And the litigation that's underway in other states now has shown just how expensive it is to sue these companies. These companies really fight hard, which means the cost of litigation can be measured easily in the millions. So some of the people who questioned this law, were saying, Vermont is too small to take this on, let some of the bigger states do it, let New York do it. And we can follow in their wake, right, but don't take the first hit from these companies. And so those costs of litigating against the oil companies, not only are they not small, but there's not enough money in Vermont to do everything that needs to be done. So that's the big question is, what's the best use of the money we have? Is it to fight the oil companies to try to get them to pay? There's a good case to be made that that's appropriate. But the contrary case is, that's going to take a really long time, with uncertain results. And so maybe the better approach is to spend the money you do have with direct assistance to the communities most affected by climate change, and let some of these other states go first.

BELTRAN: What do you think are the broader consequences of this law in Vermont? How will this impact the rest of the country and potentially the rest of the globe?

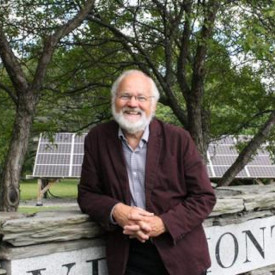

Pat Parenteau is emeritus professor of law at Vermont Law School and formerly served as EPA Regional Counsel. (Photo: Courtesy of Vermont Law and Graduate School)

PARENTEAU: I do think we're going to see other states adopting similar legislation. And I do think the underlying theory of these laws, that the oil companies should pay their fair share to address the damage that's being done, even if their product was a valuable product for many years, the truth is, we now know, it's causing damage. And under the "polluter pay" rule, which is one of the pillars of environmental law and policy, really, what Vermont is doing and what I think many other states are going to be doing is looking to the oil companies, which are some of the wealthiest companies on earth, to pay their fair share for the damage that's being done. So in that sense, I think this movement that Vermont has begun has merit. And I think it will put greater pressure on the oil companies to either agree under some circumstances to contribute to the costs of dealing with climate or be forced to do so by a court at some point. So I think there's a legal and a moral case to be made for holding companies responsible. And we'll now see how fast that can happen.

BELTRAN: Pat Parenteau is former EPA regional counsel and emeritus professor at Vermont Law and Graduate School. Thank you, Pat, for joining us.

PARENTEAU: Thank you, Paloma. It's a pleasure.

BELTRAN: We reached out to the American Petroleum Institute for comment and they responded in part, quote: “This bill is nothing more than an unnecessary new fee on American energy that would only stall the innovative progress underway to accelerate low-carbon solutions while delivering the energy communities need.” To read the full response, head on over to our website, loe.org.

--

FULL STATEMENT FROM THE AMERICAN PETROLEUM INSTITUTE: “America’s natural gas and oil industry is working to address climate change and build a lower carbon future, while simultaneously meeting the world’s growing energy needs. This bill is nothing more than an unnecessary new fee on American energy that would only stall the innovative progress underway to accelerate low-carbon solutions while delivering the energy communities need.” – Scott Lauermann, API Spokesperson

--

Related links:

- Vermont’s Climate Superfund Act

- Vermont Natural Resources Council | “Climate Superfund Act Passes Vermont Legislature, Heads to Governor Phil Scott”

[MUSIC: Stan Samole, “Row Row Row Your Boat” on Childish Dreams. MAPL In the Public Domain, MCA Records Canada for JAZZ INSPIRATION Records]

O’NEILL: Just after the break, environmental champions from around the globe. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Thelonius Monk, “Dinah (Take 2)” on Solo Monk, by Hakst-Lewis J Young, Columbia/Legacy for Sony Music Entertainment]

The "Little Sea" with a Big Champion

Teresa Vicente is a professor of philosophy of law at the University of Murcia. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

BELTRAN: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Paloma Beltran.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

The Mar Menor or “little sea” lagoon on the coast of Murcia, Spain, used to be a pristine saltwater home to a vital marine ecosystem. But mining, agriculture and a booming tourist industry have threatened this fragile coastal area. Teresa Vicente is a professor of philosophy of law at the University of Murcia, and she spearheaded a grassroots movement to protect the beloved Mar Menor. Her work led to the passage of a law in 2022 granting the lagoon legal personhood, the first recognition of legal rights for a European natural feature. For her activism, Teresa was granted the 2024 Goldman Environmental Prize for Europe, and she joins me now. Teresa, welcome to Living on Earth!

VICENTE: Thank you very much. I'm very happy to be here with you.

O'NEILL: So tell me about the Mar Menor, or “little sea” lagoon in Murcia, Spain. What is so special about this ecosystem?

Ms. Vicente spearheaded a movement to provide legal personhood to Mar Menor, the largest permanent saltwater lagoon in Europe. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

VICENTE (TRANSLATED): Mar Menor is a saltwater lagoon that's 130 square kilometers with a sand dune that separates the lagoon from the Mediterranean. These sand dunes used to be marvelous, but now they're occupied by unsustainable urbanization. And the basin of the lagoon, which also has rights because it's in the same ecosystem, is 1,660 square kilometers. Since the 1960s, it's been severely impacted by the mining industry because the runoff from mining would spill and make its way into the lagoon. During the 70s, there was a lot of development and urbanization in the watershed and basin. And in the 80s, the agricultural industry and intense cattle farming really provoked the lagoon's collapse. And in recent decades, agriculture and livestock have definitely been the biggest threats to the lagoon.

O'NEILL: And Teresa, with all of these issues, what inspired you to work to protect Mar Menor?

VICENTE (TRANSLATED): For all Murcians, as well as for the Spanish community, but especially for Murcians, the Mar Menor is a vital part of our cultural identity. We're emotionally attached to it, and it forms an integral part of our lives. And in 2016, when Mar Menor's wildlife was dying right in front of our eyes, that's when the community started to wake up to what was happening. I'm from the generation that’s seeing the effects of climate change firsthand. So I started to ask myself, why does social responsibility law not account for how humans are responsible for the destruction of nature? And I had already been studying for a while the possibility of granting rights to nature. So I presented my idea to the community and they agreed that we need to recognize and defend the lagoon and its right to live.

In recent decades, rapid urbanization and a tourist boom have threatened the ecosystem. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

O'NEILL: And so you've been working on this for a number of years. You were even collecting signatures during COVID-19 lockdowns. What steps did you have to take in order to move this idea from, we should get legal rights to this lagoon, to actually getting the Spanish government to agree and grant these rights?

VICENTE (TRANSLATED): So when the great die-off happened in Mar Menor in October of 2019, I was studying at Reading University in the UK, and I was already looking into previous international legal cases that resulted in the recognition of rights of nature. I was studying what legal steps you have to take to turn a philosophical idea into concrete rights for nature. The two biggest examples I found were the Rio Atrato in Colombia, and the other case was the Whanganui River in New Zealand. So I learned what processes worked in those cases and then researched a plan for Mar Menor alongside my law students at the school. At that time, there was already a social movement that involved asking politicians and scientists why Mar Menor had been damaged, and what kind of solutions could fix the problem. And I was one of the professionals asked to participate. During a meeting at the public plaza, I explained my research and argued that the solution was to recognize that Mar Menor is living, and it has a right to life. That is, it has the right to be protected, to be repaired, to be conserved. And at that moment, the people involved in the movement transformed their sadness into happiness and their desolation into hope. And that's when we realized we were all going to fight together to make sure Mar Menor had its own rights.

Ms. Vicente has studied the rights of nature for decades and used her knowledge to fight for the protection of Mar Menor. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

O'NEILL: So as I understand it, this is the first time an ecosystem in Europe has been afforded these legal rights. It's really groundbreaking work. What does this new legal status mean for Mar Menor, and what are you hoping it'll mean for the future of environmental protection?

VICENTE (TRANSLATED): The significance of this win is that Mar Menor has received its rightful recognition as another living being that is part of humanity. It means that we're not separate from natural ecosystems, but we're alive thanks to them. Our human development models have to work within the limits of the natural world. We have to respect nature, live in harmony with it and not just use it for economic gain. I hope that this can set an example all across Europe and help the communities that are fighting for the rights of endangered ecosystems.

O'NEILL: Teresa Vicente is a Goldman Prize recipient and professor at the University of Murcia. Teresa, thank you for joining us today, and congratulations.

VICENTE: Thanks a lot.

Related links:

- Watch Teresa Vicente’s profile video from the Goldman Environmental Prize

- Read Teresa Vicente’s profile from the Goldman Environmental Prize

[MUSIC: Joshua Bell & Edgar Meyer, “BT” on Short Trip Home, by Edgar Meyer, Sony Classical]

Uncovering the Truth About Beef and Deforestation

Marcel Gomes is the executive secretary at the nonprofit media outlet Repórter Brasil and leads the organization’s investigations and research teams. He is the 2024 winner of the Goldman Environmental Prize for Central and South America. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

BELTRAN: The Brazilian cattle industry is responsible for around 20% of the world’s beef exports. But cattle need lots of land to graze, and to make space, ranchers set massive fires to clear the forests. Marcel Gomes is the executive secretary of the nonprofit media outlet Repórter Brasil and the 2024 Goldman Environmental Prize winner for Central and South America. Gomes and his team conducted research to prove a direct link between the meatpacking company JBS and illegal deforestation in Brazil. The native ecosystems under threat include not only the Amazon rainforest but also the savanna known as the Cerrado and the tropical wetland called the Pantanal. I asked Marcel what makes these ecosystems so important.

GOMES: First of all, they are a very important source of water resources for Brazil and for other countries. The main rivers from Brazil are crossing the area, or the origin of these river are those areas. So it's very important for water supplying the big cities in Brazil. The second issue is a climate issue. We know that Amazon is a big tropical forest that regulates the climate not only in Brazil, but the entire planet. So it's very important to preserve the forest. I'm journalist. So I think it's very important for journalism to speak about these issues related to not only the forest itself, the importance of preserve that area of Brazil, but also to know that there are a lot of communities, traditional communities, indigenous populations, quilombolas, which are the descendants of the former slave people, to talk about the impacts that has been affecting these communities in the Amazon and the other biomass.

BELTRAN: And how have indigenous populations in the Amazon rainforest been impacted by the cattle industry?

GOMES: Yeah, so the Brazilian herd is expanding to the Amazon, and now more than 40% of the Brazilian herd is in Amazon. Of course, this is causing deforestation. And we know that indigenous people depend on the forest to live. It's from the forest they get resources, they get food, water. Without forest, we don't have indigenous communities, and you don't have this traditional population living in that area.

Deforestation from the cattle industry in Brazil threatens major ecosystems including the Amazon rainforest, the biodiverse savanna known as the Cerrado, and the tropical wetland called the Pantanal. (Photo: Fernando Martinho)

BELTRAN: You've done incredible work proving the direct link between the meatpacking company JBS and illegal deforestation in Brazil. What makes this work so important?

GOMES: Cattle industry is a powerful sector, economic sector in Brazil. Brazil it's a major exporter of beef. The cattle industry is also a source of biofuels. For example, biodiesel in Brazil, 20% of the Brazilian biodiesel is made by animal fat. Also, the leather is used by the car industry to build the seats of cars, and also by the garment industry. So it's a very powerful and interconnected industry. But at the same time, it's source of illegal deforestation, modern slavery, contamination of water resource, so a lot of problems. So it's important to investigate the industry in order to provide more transparency about the supply chains, and start dialogues with companies and authorities about the impacts they have been causing, and discuss how to address these issues and improve the mode of production.

The Amazon rainforest is crucial to regulating the climate not only in Brazil, but across the planet. (Photo: Fernando Martinho)

BELTRAN: And as part of your research, you tracked the deforestation in the Amazon rainforest. You tracked which land was cleared for cattle, and for what company. How did that happen, and what makes this work so difficult?

GOMES: Yeah, first of all, there is no transparency in the industry. If you contact any company and request information about the suppliers, you don't receive this kind of information. Because of this, investigative journalism it's a source of that kind of information. So we worked for almost one year in partnership with international organizations. In Brazil, we investigate the first part of the supply chain, particularly the connections between the ranch and the slaughterhouse. So we used data, public data, to provide these connections, and also in order to identify the destination of the Brazilian beef, we hired researchers in different countries, in different cities in Europe, in the U.S., even in Brazilian cities, and the researchers, they went to supermarket stores in order to take pictures of the Brazilian meat. And through those pictures, we are able to identify the slaughterhouse which are supplying the beef to the supermarkets. Then we have 100% of the supply chain traced—the whole supply chains, from the ranch to the supermarket. So it was a lot of work. We explored the supply chain of the three major slaughterhouse we have in Brazil, JBS, Marfrig, and Minerva. And we published a very important report that caused a big impact against the industry.

BELTRAN: And as a result of your team's investigations, six major European market chains committed to stop selling JBS beef products. And some of them actually promised to stop selling all beef products from Brazil. Why focus on the European market?

An aerial image of an agricultural field and illegal forest burning in Brazil. (Photo: Fernando Martinho)

GOMES: Some European countries, they have due diligence legislation. So that's very powerful, because companies are not only taking care of the supply chain because the consumers like it, but it's mandatory according to the legislation. So when we offer evidences that there are problems in the origin of the beef, then you can discuss next steps related to litigation, for example, based on the due diligence legislation the country has. So it's really powerful when we focus on countries like France, where they have these kind of legal frameworks.

BELTRAN: How did JBS react to your investigation and all of these boycotts?

GOMES: JBS has a strong department of PR, of course, they have been publishing what they have been doing in terms of reaction, how they have been improving, according to, to them, the monitoring and the control of supply chains. Some years ago, they launched a new framework for the sustainability policies. What's good, we are happy that they have been trying to get some improvements. But our main point is that not only JBS but the other major slaughterhouse, they don't have monitoring 100% of the supply chains. The cattle doesn't stay the whole life in the same area. The farms, the ranches, they are specialized in parts of the cattle life. So the cattle, besides reach the slaughterhouse, they can pass three, four, five farms. And we know in Brazil that the problem nowadays is more concentrate in the indirect suppliers. So our main request for the industry is that is important to monitor the whole supply chain, not only of the last farm, which is what they have been doing so far.

Marcel Gomes accepted his award at the 2024 Goldman Prize ceremony in San Francisco. An investigative report by Gomes’s team at Repórter Brasil led six major European supermarket chains to stop selling products from the meatpacking company JBS, which the report directly linked to deforestation in Brazil. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

BELTRAN: What other changes would you like to see to address deforestation in Brazil?

GOMES: The government is particularly interested in reducing the deforestation in Amazon, and deforestation rates in Amazon are going down. Unfortunately, the deforestation rates are still going up in Cerrado. In most of Cerrado, according to legislation, you can deforest about 80% of the farm. It's legal. So we need that the government address the deforestation, even the legal deforestation in Cerrado. Because it is possible, according to the specialists we have in the country, to expand the production of food in Brazil, the production of soy, the production of cattle, without deforesting any new hectare in the country. So that's our point: we need in the next couple of months to reduce deforestation in Cerrado, doesn't matter if it's legal or illegal.

BELTRAN: Marcel Gomes is the 2024 Goldman Environmental Prize recipient for South and Central America. Thank you for joining us.

GOMES: Thank you very much, Paloma.

Related links:

- Watch Marcel Gomes’s profile video from the Goldman Environmental Prize

- Learn more about Marcel Gomes on the Goldman Prize website

- Repórter Brasil| “Meat Exports Connect Deforestation in Brazil to Large Global Retailers” [NOTE: Article is in Portuguese]

- Retailers’ responses to the 2021 Repórter Brasil investigation

- Reuters| “European Supermarkets Stop Selling Brazil Beef Over Deforestation Links”

- JBS’s sustainability page

[MUSIC: No em pingo D’agua, “Assanhado” on Visom-A Windham Hill Sampler, by Jacob do Bandolin/arr.Rodrigo Lessa, Windham Hill Records]

From the History Books

A snowy egret (Egretta hula) displays its plumage. Under threat of extinction in the early 20th century, the snowy egret is now in the “Least concern” category. (Photo: William H. Majoros, Wikimedia Commons, CC-BY-SA 4.0)

O'NEILL: Joining me now on the line is Peter Dykstra, the Living on Earth contributor who is here to bring us a couple of stories from the history books. Hiya, Peter, what do you have for me this week?

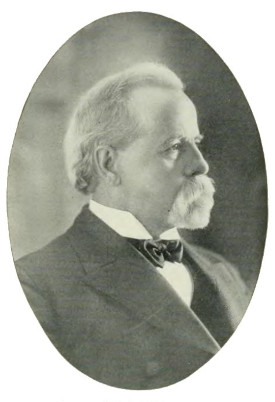

DYKSTRA: Hi Aynsley, a couple of things that go back over a century. The first one, May 25, 1900. That's the day that the U.S. President William McKinley signed the Lacey Act. Lacey was one of the first sweeping wildlife protection laws. It limited the interstate and international trafficking in fish, birds, mammals and plants. Of particular interest is that birds with colorful plumage were being wiped out to help suit the fashion industry of the day, particularly ladies' hats that tended to have a lot of elaborate feathers. And the Lacey Act, along with the establishment of National Wildlife Refuge in places like Louisiana and Florida, helped curb the impact of the wild fashion rage that had gripped the country around the turn of the 19th century to the 20th.

Congressman John F. Lacey from Iowa received the title of “Father of Federal Conservation Legislation” for introducing the Lacey Act in the House of Representatives. (Photo: Benjamin Franklin Gue, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

O'NEILL: Yeah, the Act was designed to protect species like the Snowy Egret, which had this beautiful plumage, and I believe now in the 21st century, it's marked "least concern." So it looks like for the Snowy Egret, it did its job of protection.

DYKSTRA: And unfortunately, it didn't protect presidents from being shot. And little more than a year later, President McKinley was assassinated. His vice president, one of the great conservationists of the day, Teddy Roosevelt, took office in October of 1901.

O'NEILL: Okay, and Peter, what else do you have for me this week?

DYKSTRA: A few years before that, on May 28, 1892, the Sierra Club was founded in San Francisco with 182 charter members. The president elected in that founding meeting was John Muir. He led the effort to preserve the Hetch Hetchy Valley, and the Yosemite area in central California, which has gone on today to be one of our most popular, most visited national parks. Muir was a consummate conservationist for his day. But like many leaders back then, he very freely dissed African Americans and Native Americans, and that puts things in a little different light for what a 19th-century conservationist was and what a 21st-century conservationist ought to be.

A photograph from 1909 depicts naturalist John Muir (front, on the ground), accompanied by a group from the Sierra Club hiking on a trail. (Photo: George R. King, Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

O'NEILL: Yeah, John Muir's legacy is—it’s definitely complicated by all that racism. Alright, Peter. Well, thank you for that trip back in time. Peter Dykstra is a regular contributor to Living on Earth, and we will talk to you again soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, Aynsley, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

O'NEILL: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth website. That's L-O-E dot O-R-G.

Related links:

- More about the Lacey Act and its amendments

- More about the Sierra Club’s history

[MUSIC: Sultans of String, “Gymnorumba” on Yalla Yalla! By McKhool/Laliberte/arr.Sultans of String, Ontario Arts Council]

BELTRAN: Coming up, “the drowning south” as seas rise along the Gulf Coast. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Stan Samole, “A Froggy Went A Courtin’” on Childish Dreams, MAPL In the Public Domain, MCA Records Canada for JAZZ INSPIRATION Records]

The Drowning South

The Southeast United States has seen roughly equivalent sea level rise since 2010 as it saw in the 50 years before that. In this photo from September 2023 water pools on the Causeway in Mobile, Alabama. (Photo: Ricky Carioti/The Washington Post)

O’NEILL: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

Sea levels are rising everywhere due to climate change, but not equally. The U.S. Southeast is experiencing an especially rapid rise. A recent Washington Post series called “The Drowning South” found that since 2010, seas have risen as much as they had over the previous half century. Some communities are even deeper underwater because of sinking land and extreme rain events. Washington Post journalist Chris Mooney was part of a team that put together the Drowning South series, and he’s here now. Chris, welcome to Living on Earth!

MOONEY: Thank you for having me.

BELTRAN: So you call this series “The Drowning South.” What did your analysis find?

MOONEY: What we did was we looked at federal sea level data and tide gauges all around this region. It turns out there's been a very rapid recent acceleration in the rise of the sea. And if you just take it from 2010 to the present, all along the Gulf Coast and up the part of the Southeast to around the Carolinas, then you're getting around six inches of change in just a little over 10, 15 years. So that's much faster than what you got in prior decades.

BELTRAN: And I understand you also looked into New Orleans, Louisiana. How did the scenario of rising seas play out there?

MOONEY: That's a little tricky. And this is where I'm from. New Orleans has built comprehensive flood protections, a really impressive system of protection from the Corps of Engineers. So they are actually well protected against most hurricanes now. What we did was we looked at Louisiana more broadly. And the protections that New Orleans has are not replicated. So if you just drive across the causeway, across Lake Pontchartrain, you know, around 20 miles to the north you’re in St. Tammany Parish. Huge growth, a lot of people going there, huge flooding problems. Lake Pontchartrain has risen at least six inches or more, because it's connected to the Gulf of Mexico. And we went and on sunny days saw the lake just swallow up a coastal road, just to give one example. So not everywhere is as well protected as New Orleans. And the impacts are throughout Louisiana, really. Another one of the biggest impacts of sea level rise is the loss of the coast, because the coast is a vast area of wetlands that protect New Orleans and other cities. And what has already been documented is that this recent fast burst of sea level rise is too fast for Louisiana's coastal wetlands to handle. Wetlands grow, to some extent, to keep up with the ocean, but not when it's rising this quickly. So researchers at Tulane University, right in New Orleans, have found that many of them are now in a "state of drowning," which is to say that they're spending too much time below the level of the water.

BELTRAN: And what about Miami and the state of Florida?

MOONEY: I mean, it's all in this region where the change has been very rapid. And so they're all going to be seeing a number of the same kinds of thing—not everybody has Louisiana's wetlands. But in general, you're going to be seeing coastal erosion. You're going to be seeing something called high tide flooding, which is that, you know, there's a tidal cycle, and increasingly at the high period of the tide, it's just a lot higher than it used to be. So things that used to be dry, always, now are starting to go under. Those could be roads; those could be people’s docks. It really depends on the location, but it's often going to be various types of infrastructure. What we also really wanted to focus on was something that doesn't get enough attention, and that is that sea level rise doesn't just act on its own. It acts in combination with other things. The number one most damaging thing that it acts alongside, in this region, we found, is rainfall. So if you have rain in a coastal city, or just a coastal area, it needs to get to the ocean to drain. Means it needs to go downhill. It needs to go downhill either in a pipe out of a city or in a river. Right? They're both sloped. Well, the sea level is now higher at the end of either of those. And so sometimes the pipes are underwater at the other end. Or the mouth of the river is maybe a—could be a foot higher. So the water doesn't get out nearly as rapidly. And so it backs up, and you get all this inland flooding, including in these events that scientists term compound events, right? So you can have extreme rain and, at the same time, you can have a quite high sea, and the water will not be able to get out, and it'll just flood inland. And so you get flooding in sunny-day conditions when the tide just comes up. But then you get potentially more extreme things when the tide is high and it's raining.

BELTRAN: And you've reported on this extensively. What are some stories that people have shared with you?

Madisonville, Louisiana’s Main Street flooded in September 2023. The water came from the nearby Tchefuncte River during high tide. (Photo: Ricky Carioti/The Washington Post)

MOONEY: You hear many, many stories of just kind of like what I told you— “my dock didn't used to go under, now it goes under. Now I have to raise it.” But we told the story in Alabama, south of Mobile, of an extreme flood that occurred, which was just in June of last year, where we were able to have an expert run a model to document that the water was deeper and the flood lasted longer, because the sea level at the end of a river called Fowl River was in a high tide flood state of the sort that we've been talking about when, it's hard to know the number, but 10-ish inches of rain fell. So it was a very extreme event. And you had water rescues occurring. We spoke with the local fire chief who was sort of having to deal with this. And he sort of drove around in the morning, because it already had been raining, looking at all the ditches, seeing how high the water in the ditches was getting, knowing that when it got onto the roads, he would have to call out everybody he could, start shutting them down. It did keep raining. And then pretty soon, they were having to bring people back to the firehouse. Then it kept raining, and there were places they couldn't get to, where people were stranded. And they had to call the City of Mobile to come on down, because this local fire department didn't have a boat. So they needed different fire department to come down and conduct water rescues.

BELTRAN: And some of your reporting has shown that people of color and lower socioeconomic groups often bear the brunt of this heavy flooding. How has that played out in Mobile, Alabama?

Tug boat construction in Coden Bayou in Bayou La Batre, Alabama. (Photo: Jahi Chikwendiu/The Washington Post)

MOONEY: Mobile has just done a new report under their resilience officer, Casi Callaway, who spoke with us for this project. And in their own city report, they acknowledged that the historic legacy of redlining has created a situation in which people of color in the city of Mobile are more likely to experience flooding. So Mobile is basically aware of, and has researched for itself, sort of the growing literature that shows that some of the historic housing policies that were highly unequal and still have a legacy today are now contributing unequally to climate change risks. And flooding is one of those. And in fact, in many cases, communities that were once redlined tend to be lower lying, that’s one of the reasons. But also because it's sort of a cycle that fed upon itself, might have received lower investment in terms of drainage infrastructure, which you need to get water out, and also might have more pavement, fewer trees. And if there's more pavement, then that means water also doesn't drain into the ground, so it can rush around and flood people, so. I mean and I think we saw in extreme events like Katrina and other hurricanes, how flooding impacts are not equal.

BELTRAN: What are some of the roadblocks that communities across the South are experiencing when it comes to adapting to increasing sea level rise and increased flooding?

1. For the last year, I’ve been buried in a project that merges together data journalism with storytelling from the region I grew up in – the U.S. South, and especially the Gulf Coast. Today, that project started to publish.

— Chris Mooney (@chriscmooney) April 29, 2024

MOONEY: It's really a money issue. Because, you know, you essentially have roads and drainage systems and sewer systems and many other kinds of things that are all just lower, right? And they're lower than they used to be relative to the height of the water. And frequently these, these cities are old. They were built a long time ago, hundreds of years ago—Mobile, Pensacola, New Orleans, right? They've got long histories. So when they were established, they were established against a sea level that's really different. I mean, there's been a fast recent change, but there's also been a several-hundred-year change, and the trend has been up the whole time. So it's just very hard and expensive to adapt.

BELTRAN: What are some of the solutions that local authorities are applying? And how much is that going to cost?

Reporter Chris Mooney covers energy and environment for the Washington Post. He's worked with a team of writers to cover the intensifying sea level rise in the Southern United States with his series, "The Drowning South." (Photo: Courtesy of the Washington Post)

MOONEY: Well, that's the real thing. And, you know, if you're willing to spend enough, you can raise anything that you want. Or, in the case of Galveston, pumps that cost many tens of millions of dollars are also able to overcome what we discussed, which is gravity, right? You need—normally, gravity is taking the water out, but if the water at the receiving body, the ocean, is too high, gravity starts to fail for you. But a pump, you know, will give you force, again, behind the flow of that water. So you can do this, and New Orleans has pumps, because it's, it's so low. So you can spend money, but it's a lot of money, right? Because you have to think about all the kinds of things—a lot of roads are increasingly too low. So they will go under at high tides. You have this sort of happening throughout the region’s—you can elevate a road. But every time, you know, you're talking in the millions of dollars.

BELTRAN: Chris Mooney is an environmental reporter for the Washington Post. Chris, thank you so much for joining us.

MOONEY: Thank you for having me.

Related links:

- The Washington Post series “The Drowning South” details rapid sea level rise along the coast of Southern states

- Maps showing sea level rise from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

- Lean more about the impacts from sea level rise on home values in Alabama and elsewhere

- Learn more about the U.S Army Corps of Engineers’ project to protect the coastline from storm surges and other forms of flooding

[MUSIC: Trombone Shorty, “Hurricane Season” on Backatown, The Verve Music Group]

Sounds of Soil

Listening to sounds in the soil is a minimally invasive way to measure biodiversity underground. (Photo: Courtesy of Baker Consultants Ltd.)

O’NEILL: When you step outside on a warm sunny day, you might hear birds chirping, squirrels chittering, or even the telltale rattle of a snake. But ecologist Carlos Abrahams spends his days with an ear to the ground. Carlos specializes in ecoacoustics, the study of sound in the environment. And his recent work focuses on finding a way to link the sounds of the dirt under our feet to soil health. Healthy soil needs biodiversity, so his work listens for slithering earthworms.

[EARTHWORM SFX]

O’NEILL: Marching ants.

[ANTS SFX]

O’NEILL: And tunneling voles.

[VOLE SFX]

O’NEILL: With the idea that these signs of life can tell us just how well the soil’s doing. Carlos Abrahams joins us now for more. Welcome to Living on Earth, Carlos!

ABRAHAMS: Thanks for having me. Great to be here.

O'NEILL: So Carlos, what do we know about the link between soil sounds and soil health?

Dr. Abrahams’ research aims to use soil acoustics to help sustainable agriculture measure improvements in soil health. (Photo: Courtesy of Baker Consultants Ltd.)

ABRAHAMS: So we think those two things are linked together. And we know that in other environments aboveground, we get good links between the sounds that are produced in an ecosystem and species diversity, species richness. That's been shown in various places around the world. So taking that learning from aboveground, we're hoping to apply the same sort of principles to the sounds from soil as well. And it does seem to be, from the initial work that ourselves and other people have done, that where you have diverse sounds, that is a good indicator of good environmental health, good land management practice, and lots of fauna in the soil, so a biodiverse soil fauna. Where we have poor sounds within the soil and they aren't complex, and there's not much going on, then that's often an indicator, for example, of bare soil, or one that's been highly agriculturally improved, and had lots of chemicals put into it potentially. So the work that we've done and other people have done have sort of given us a good nod in the right direction that if we take sounds from the soil and analyze those, they will be a good indicator for soil health, soil biodiversity.

O'NEILL: And so once you have this recording, how do you learn from it? How do you figure out what that says about the soil?

ABRAHAMS: Okay, so these days, we have two main ways to take sounds from the environment and use those to study wildlife ecology. And one way is to try and recognize the individual voices of different birds or different bats or different sorts of soil fauna, whether that's earthworms or beetles. And aboveground, there's been lots of development of that. So some of the universities in the States have done superb work in terms of building recognizers that the you can now take a recording, hit it with their fantastic AI algorithms, and it will tell you what bird species it is. And we have similar recognizers that do that for bats as well. And we can do that pretty well for a whole range of different species underwater as well. The unfortunate thing is that we don't have enough recordings from known species within the soil at the moment to build up a library and a classifier to allow us to know what is making what sound. One of the big parts of the projects we're currently doing for the UK government at the moment with this grant scheme is to try and do that. So we have buckets of different sorts of worms, and we're trying to record one type of worm versus another worm versus woodlice versus centipedes, whatever it might be. So that's the first approach. The other approach that’s become available in the last 10 years or so is not to try and identify species, but to use an acoustic index that allows you to take a recording and analyze how complex the sound is within that recording. So we can take a one-minute sound file, and if there's lots of different things going on, there's lots of sound being produced, then we can give that a number. We're hoping that we can link that to good soil health or good land management practice. And if those sounds are very quiet, there's not much going on, then we know that there's not much fauna activity within the soil. And that's possibly, probably going to be related to poor soil health.

In addition to collecting audio from natural and agricultural environments, Abrahams studies the sounds from controlled lab environments. His team hopes to build a library of the sounds of individual species. (Photo: Courtesy of Baker Consultants Ltd.)

O'NEILL: It sounds like a lot of what you're learning from your ecoacoustics work might help in boosting soil quality, and specifically in the agricultural field at that. So what kind of challenges are farmers currently facing with regards to soil quality?

ABRAHAMS: So when we are looking at soil health, and we need to put air quotes around that, because it's not a very well-defined term, we can go and do physical measures. So farmers are used to dealing with things like pH levels or alkalinity of their soil. But in terms of trying to assess the biodiversity within soil, that's really hard to do. And there are very few good methods that are available for that. The great thing about the soil recordings is that it's pretty lightweight. You can take lots of recordings across the field. It's quite easy to do. It's pretty quick. It's fairly cheap in terms of recording and analyzing those. And we're hoping to prove it gives a good indication of how healthy that area of soil is there without having to go to lots of effort or lots of expense. It's a new, hopefully potentially really useful and quite easy to implement system that gives us data on soil biodiversity that we can't really get very well using other methods. So it's sort of filling a gap that farmers and other land managers are looking to try and fill at the moment. There's lots of interest in regenerative agriculture and improving soil health, how we manage soils, how we look after the environment. And new data sources like using soil acoustics are potentially really valuable in terms of allowing us to do that monitoring.

Researchers hope that soil acoustics can eventually be used to test the health of restored forests. (Photo: Courtesy of Baker Consultants Ltd.)

O'NEILL: Now, I want to zoom out a bit, because this field is really still in sort of its earliest stages, it sounds like. So what do you see as sort of the next step in specifically the, the soil side of eco acoustics?

ABRAHAMS: We need to expand those little bits of work that have been done in soil across a wide range of environments and into new places. And get people aware of it and using it within their own contexts as well, whether that is, you know, within agricultural or nature conservation, or whether it's in the restoration of contaminated land, for example, or soil storage. So we've had some approaches from building development companies who are interested in how what acoustics might tell us about soil that they have removed from the development site and stored for five or 10 years before reusing that soil for green spaces and planting within new developments. And is the soil still alive? Or is it completely dead when they're putting it back? Yeah, we're really at the start of trying to figure out how it all works, how we can use soil acoustics. The research that's been done has shown lots of promise, but really, there's a whole universe of work that still needs to be done to try and expand the boundaries of what we know.

O'NEILL: Carlos Abrahams is a senior lecturer at Nottingham Trent University. Carlos, thank you so much for joining us today.

ABRAHAMS: Thank you very much.

Related links:

- Learn more about Carlos Abrahams

- Read about the importance of biodiversity

- Explore how ecoacoustics is being used above ground

[MUSIC: Snorre Kirk, “Pastorale” on Stunt Records Compilation 25, by S. Kirk, Sundance Music]

O’NEILL: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Shanzay Asif, Josh Croom, Jenni Doering, Karen Elterman, Swayam Gagneja, Sommer Heyman, Mattie Hibbs, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari.

BELTRAN: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Allison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at loe.org, Apple Podcasts and YouTube Music, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments@loe.org. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Paloma Beltran.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth