June 14, 2024

Air Date: June 14, 2024

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Beirut's Deadly Air

View the page for this story

Clouds of diesel fumes clog the air in Beirut, Lebanon where the virtual collapse of the power grid has led residents to rely on diesel generators. The city’s air is now so badly polluted researchers at the American University of Beirut are linking it to a startling 30% spike in cancer cases. Chemistry professor Najat Saliba, who is also a member of Lebanon’s parliament, joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss the health toll of this pollution and its roots in Lebanon’s debt crisis. (12:19)

From the History Books

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Living on Earth Contributor Peter Dykstra joins Host Steve Curwood to look back on the 1944 creation of Big Bend National Park, renowned for its Chihuahuan Desert ecology and dark skies. They also go further back in time to the 1889 New York law mandating that all electric and phone lines in New York City and Buffalo be placed underground. (03:07)

Queer Brown Vegan

View the page for this story

Isaias Hernandez is an environmental activist and social media creative who uses the handle @QueerBrownVegan on Instagram, TikTok and YouTube. His topics include environmental racism, mushroom foraging, and queer ecology. He joined Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran during Pride Month to talk about intersectionality, “rainbow-washing”, and more. (12:49)

Roots of Black Hair Care

View the page for this story

Hair care products marketed to Black women today often include cancer-causing formaldehyde and hormone disrupting chemicals. But back in the early 1900s, an enterprising Black woman named Madam C. J. Walker used mostly natural ingredients in her hair products to empower Black women and become the first female American self-made millionaire. Host Steve Curwood talks with her great-great granddaughter, A’Lelia Bundles, who wrote the 2001 book On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker. (19:10)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

240614 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: A’Lelia Bundles, Isaias Hernandez, Najat Saliba

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

Diesel generators are choking Beirut with deadly air pollution and raising cancer rates.

SALIBA: We know that the emissions of these diesel generators are going to harm us. But we are left to decide between living in a poisonous environment or living without electricity.

CURWOOD: Also, the descendant of a Black hair care pioneer on her career in television.

WALKER: One of the reasons that I chose not to take the on-air route is because I had a big Afro and I did not want somebody telling me how to wear my hair. But behind the scenes, I could wear my hair however I wanted without that kind of pressure.

CURWOOD: And celebrating Pride, we meet a “Queer Brown Vegan.” Those stories and more this week on Living on Earth - stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Beirut's Deadly Air

Pink clouds in the aftermath of the 2020 Beirut explosions. A catastrophic blast rocked Beirut's port resulting from the detonation of hundreds of tons of ammonium nitrate, a fertilizer material with highly explosive properties. (Photo: Freimut Bahlo, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

[GENERATOR SFX]

CURWOOD: Clouds of diesel fumes constantly clog the air in Beirut, Lebanon, where the noise of generators can make it hard to think or sleep. Once known as the Paris of the Middle East, Beirut is suffering a chronic financial crisis and the virtual collapse of its electric power grid. So, residents must rely on thousands of diesel generators to keep the lights on. And Beirut’s air is now so badly polluted, researchers at the American University of Beirut are linking it to a startling 30% spike in cancer cases.

One of those researchers is Najat Saliba, a chemistry professor. She’s also an air quality expert for the World Health Organization and a member of Lebanon’s parliament. Professor Saliba joins us on the line from Beirut. Welcome to Living on Earth!

SALIBA: Thank you for the invitation.

CURWOOD: If you could please begin with giving us some insight into the influx in the use of diesel generators in Beirut. Why has that happened?

SALIBA: Well, probably 10 years ago, national electricity started rationing hours of electricity for residents in the country. It started with three hours of rationing, and then it escalated into six hours. And then in 2022, the power plants and the national grid went really down. And people started relying heavily on diesel generators to subsidize the lack of electricity coming from the national grid. It is mismanagement and lack of responsibility and accountability in the way the national electricity grid and power plants were handled in the country.

CURWOOD: Now, I understand a few years back, there was a major explosion in downtown Beirut at the shipping docks. To what extent did that explosion and fires relate to this loss of electrical capacity?

SALIBA: Well, this is just another manifestation of the lack of responsibility and inefficiency and corruption in the government, whereby they store chemicals, explosives, without really taking care of them and protecting the civilians from their harms. And in the same way, this is how the power plants in the country were handled. And that's why they're leaving people without electricity, and even without really caring about their safety.

The Beirut skyline with a lingering haze of pollution. (Photo: Marviikad, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Let's talk about the pollution there now. If one uses a lot of diesel generators it, among other things, creates a fair amount of particulate pollution. How can the pollution be seen there? To what extent is this something that you notice when you step out of your house?

SALIBA: Well, it's obvious to the naked eye when you go outside Beirut, especially directly next to Beirut hills that people live in. And when they go down to their jobs to Beirut in the morning, you can see that Beirut is completely covered by a thick haze of pollution. And right now, people are asking why this haze is becoming darker and darker by the season. And in the summer, because there is no wind and no rain, we see this almost every day.

CURWOOD: Now, to what extent is this increase in the use of diesel electric generators being linked to a spike in cancer rates there?

SALIBA: So what happened is, since 2010, we have done a lot of air pollution studies whereby we collected particles from the air and we did chemical analysis. And with the chemical analysis, we did a parallel fingerprint to see what are the sources of pollution in the city. And since 2010, we have realized that over 20% of the pollution is mainly coming from diesel generators. Fast forward to 2022, we repeated the same study and we were able to compare it to previous years. This is when we found that the amount of pollution coming from diesel generators has increased to 50%. And with that comes carcinogens in the air that have led to the increase in the cancer rate by 30%. And in the cancer risk by 50%.

Dr. Najat Aoun Saliba is is the director of the American University of Beirut's (AUB) Nature Conservation Center, a member of the Parliament of Lebanon and an advisor to the World Health Organization. She has led the research at AUB on the correlation between the spike in cancer rates and the influx of diesel generators in the city. (Photo: World Intellectual Property Organization, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So what do you attribute the factors that are contributing to hazardous air quality there in Beirut?

SALIBA: So, we have done what we call a source apportionment whereby we look at the sources contributing to air pollution. And we found that the main sources of air pollution in the city of Beirut are the particles coming from diesel generators and also particles coming from the cars and the vehicles that are running on a daily basis. Again, we have no industry or very limited industrial activities, and that's why we consider those two sources as the main sources of pollution. Mind you that the car fleet that we have measured or we have assessed in 2017 have shown that the average age of the cars that are on the streets is 18 years. And with the economic collapse since 2019, it is expected that this the average age has probably went higher, meaning that the cars are much older than what we have seen in 2017, and this exacerbate the air pollution.

CURWOOD: We do know that worldwide there are about 8 million excess deaths from particulate pollution. But at this point, we don't have more precise data from Lebanon, from Beirut itself. Now, how can the lack of definitive data be explained for what seems to be really a public health and environmental health crisis there in Beirut?

SALIBA: Exactly, because the monitoring stations that were once running are now stopped. And that's why we don't have continuous data of how much particulate matter we have. The present inefficient government is a complete violation of all human rights. And it's just stripping people from their right of for clean air, clean water.

CURWOOD: Why is that? Do you think? To what extent is it related to the economic conditions there, the political conditions, to the wars nearby? What, what do you think is driving this?

SALIBA: After Lebanon has battled with civil war for around 20 to 25 years, the warlords decided to end the war and wear a suit and take charge of the government. And since then, they—and I'm talking since 1990—even though they came up with a new constitution that emphasizes reform, nothing has been done. And things have been deteriorating. And corruption has been really predominating over any reform, or any advancement and development in the country. And of course, this has its toll on, on the environment, and it has its toll on the well-being of people.

The scale of destruction caused by the 2020 explosion at the ports in Beirut. Experts have characterized this event as one of the most powerful non-nuclear explosions ever recorded in human history. (Photo: Mehr News Agency, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

CURWOOD: And as I understand it, Lebanon has been the recipient of a significant amount of international aid and some loans. What has happened to those funds?

SALIBA: That's a very, very good question, and I would like the taxpayers all over the world to ask their countries of why auditing and accountability has not been enforced on the international aids that have poured into Lebanon. And we still have very little to show for from these grants and loans. I think they have spent already $43 billion on the electricity sector. $43 billion are able to not only build a new infrastructure of electricity, they can build a country altogether. So with all this money spent on the electricity sector, we still don't have electricity. And we pay two bills, one for the government and one for the diesel generators owners, because we cannot live without it. And we know that the emissions of these diesel generators are going to harm us. But we are left to decide between living in a poisonous environment or living without electricity.

CURWOOD: So would you mind for a moment just looking up at the air quality index today in Beirut, as we're speaking? What are the numbers right now?

⚠️The sky above #Beirut now⚠️

— Jumanah Zabaneh ???? ~ جمانة (@j_zabaneh) September 8, 2023

Layers & layers of grey due to extremely high levels of #AirPollution.

The city relies almost exclusively on burning #fossilfuel by private generators for its #electricity. Solid waste & garbage are also partially managed through burning ???? pic.twitter.com/G7A6Usf6bX

SALIBA: There is no index. Because we don't have monitoring stations that are operating. So the average particulate matter 2.5 mass that we, or concentration that we have measured over the past 10 to 15 years has hovered between 20 to 25 micrograms per meter cubed as an annual average. And this is at least five times higher than what is recommended by the World Health Organization. So unfortunately, the lives of people here are not really attended for. They are forced to close their windows, winter and summer. Because the sound, the noise of the diesel generators, the smell from the diesel that comes up, and the smoke, all of them can fill up the house.

CURWOOD: So what's the mood among the public there in Beirut, in Lebanon about this? What's the political impact of this?

SALIBA: We can say that a lot of people are really upset from the ruling warlords, but at the same time, these people have created a deep state whereby a lot of people's lives depend on them. And that's why it's very difficult to say that the people have really the freedom to choose between them and other candidates. Because clientelism and dependency have been entrenched in people's lives. And that's why those rulers have become like dictators.

CURWOOD: Indeed. Dr. Saliba, what kind of mitigation plans are in place, if any, right now to, to try to turn this situation around?

SALIBA: So what we're trying to do is now putting a lot of pressure through media and through publications and through press releases on the executive branch of the government to actually implement some regulations on these diesel generators to reduce emission, while also demanding for a 24 over 24 electricity coming from the national electricity company. We are also in the process of communicating this with the judiciary in order for them to be able to enforce the decrees that have been issued by the Ministry of Environment in terms of regulating how diesel generators operate in order for the emission to be regulated and reduced.

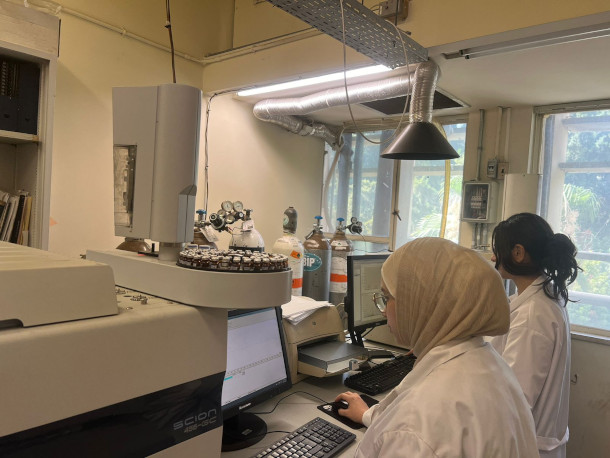

Dr. Saliba’s students conducting chemical analysis as part of the research on diesel generator emissions at the American University of Beirut. (Photo: Courtesy of Najat Saliba)

CURWOOD: Najat Saliba is a World Health Organization adviser on air pollution, also a professor and researcher at the American University of Beirut and a member of parliament in Lebanon. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today, Dr. Saliba.

SALIBA: Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: Our direct requests for comments from the Lebanese government so far have gone unanswered. We did find that Nasser Yassin, the Minister of Environment in Lebanon’s caretaker government, was recently quoted in the Lebanese publication, The National. He said, “The presence of this large number of generators and their use most of the time is an anomaly and should be reduced through better and cleaner sources of electricity.” But he did not offer a timetable for a solution.

Related link:

The Guardian | “‘Where Can You Hide from Pollution?’: Cancer Rises 30% in Beirut as Diesel Generators Poison City”

[MUSIC: Billy Esteban, Café Anatolia, YouTube]

CURWOOD: Coming up after the break, celebrating Pride Month with queer ecology and more. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: The Dave Brubeck Quartet, “Take Five” on Time Out, Sony BMG Music Entertainment]

From the History Books

The Chisos Mountains in Big Bend National Park. (Photo: Jonathan Cutrer, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

And on the line now from Atlanta, Georgia is Peter Dykstra, taking a look at the history books for us today. Hey, Peter, what do you see?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve. We see a couple of things. Going back first to June 12, 1944. Big Bend National Park is established in Texas. Located along the banks of the Rio Grande River. The park features absolutely undisturbed ecology of the Chihuahuan Desert. The park is also valued as a treasure trove of Native American artifacts and history.

CURWOOD: It is a pretty amazing place. They have a lot of endemic species, plants and animals, and great places to hike. And it's actually linked with natural areas across the border in Mexico. Maderas del Carmen, Cañón de Santa Elena, and Ocampo, which means that Big Bend is part of something like 3 million acres of Chihuahuan Desert resources. And one of the coolest things about it is that this is one of the best dark sky places in the United States, one of the best places for night sky viewing.

DYKSTRA: Absolutely. And there's so much to see in a truly dark sky. And a dark sky place literally in the middle of nowhere is, is one I wouldn't mind spending a little bit of time.

CURWOOD: Hey, from Big Bend, let's take a turn to another story.

DYKSTRA: And take a turn to another century, the 19th century with a really foresightful gesture by the New York State Legislature. June 14, 1889, New York voted to literally clear the air, outlawing overhead electric lines in its two largest cities, Buffalo and of course, New York City. All telegraph, telephonic, and electric light wires and cables must be placed under the surface of the streets, lanes, and avenues. Just in time for a boom in electricity and all the things that it brought us at the end of the 19th century.

New York City’s Flatiron Building, with nary an electrical pole in sight. (Photo: Victoria Pickering, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Right. And it's protected New York City from losing electric power randomly when there's a big windstorm because, you know, when the wires are underground, they're not affected by the wind. And it's really made the place look a lot better. Just imagine for a moment a picture, say of the Flatiron Building. And there's no telephone poles in it. Almost any other city, if you see nice architecture, the photographer has to work around those, those wires and poles, but not in New York City.

DYKSTRA: Well, Steve, as you know, I grew up in a New York City suburb that, to this day, still has overhead wires helping to block the view.

CURWOOD: It was over 100 years ago that we had this insight, but some places are just plain behind the times. Hey, thanks, Peter. Thanks for these stories from the history books. And we'll be talking to you again real soon. Peter Dykstra is a contributor to Living on Earth.

DYKSTRA: All right, Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on the stories from the history books at LoE.org.

Related links:

- Learn more about New York City’s underground electrical grid

- Big Bend National Park at the National Park Service

[MUSIC: Hugo and Marina Andrade, “New, York, New York” theme from Martin Scorsesa’s “New York, New York,” music by John Kander, lyrics by Fred Ebb, YouTube]

Queer Brown Vegan

Isaias Hernandez is the environmentalist and media creative behind the platform Queer Brown Vegan. He has an environmental science degree from UC Berkeley and lives in Los Angeles, California. (Photo: Courtesy of Isaias Hernandez)

CURWOOD: Isaias Hernandez is an environmental activist and social media creative living in Los Angeles who goes by the moniker Queer Brown Vegan. His topics include environmental racism and food justice as well as more lighthearted content, like his mushroom foraging. As a queer Latino in the eco space, Isaias is the kind of public figure he didn’t see many examples of as a kid. Now he uses his platforms on Instagram, Tik Tok and YouTube to make environmental education more accessible and help people feel more at home in a world that is remarkably queer. Nature, he notes, does not always insist on sharp gender divides, with diversity that includes such examples as bisexual bonobos, lesbian albatrosses, and fish that change sex. Isaias Hernandez joined Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran during Pride Month to talk about queer ecology and more.

HERNANDEZ: Queer ecology offers us a critical lens to understand relationships beyond the narrative of the binary. So when we look at fungi, flora and fauna, these species are not constrained by the human society standards that we follow, right? So I think that the important thing to understand with queer ecology is that it allows us to challenge the norms of what is natural versus unnatural, and deconstruct those power structures that we have in our society that is very obsessed with labeling people and contributing to the otherizations of queer and trans identities, when we know that queer and trans people and two-spirit individuals have always existed and have been documented throughout history. So in many indigenous cultures, there are certain people who never identified with the male or woman role. And so these cultures are very rich in their understanding of the celebration of these gender diversities. Unfortunately, due to settler colonialism and religious ideologies, we start to see this disconnection and this disapproval of these identities. And so I think, to me, it's really important to know that when you learn about queer relationships, you're not just talking about gay penguins and bisexual flowers; instead, the ways in which academia approaches it validates the fact that animals have a very unique relationship with polyamory, or asexual reproduction, and that these are not so much "unnatural" incidents, but natural processes. When we talk about these species engaging in queer behaviors, it's not so much that queer and trans people are saying, like, "Look, if this is normal, then we are normal," it's allowing us to say, like, we as people are nature. We have allowed ourselves to be constrained by cis heteronormative views, and a lot of humans today here in America have become heavily severed from our relationship to what we are as nature, which is why we see a lot of conversations of humans in nature, not so much humans are nature.

BELTRAN: And you've also said that homophobia and transphobia runs rampant in the environmental movement. How have you seen that in practice?

HERNANDEZ: Historically, one, the environmental movement has excluded many Black indigenous people of color. The second thing is that these conservationists, a lot of them have failed to include intersectionality in their understandings of why these landscapes are degrading. To look at the larger corporatized and monopolized industries that have really contributed to the degradation. So in my experience in dealing with the environmental movement, typically, cis heteronormative men that have large power dynamics that also flex not just homophobia, transphobia, but sexism, misogyny, these are not isolated responses. In my experiences of being challenged and interrogated, it's often come with people who are threatened by my ability to challenge them. They believe that talking about your identity is irrelevant to nature. And so I think bringing out my queer identity is very important to me in this movement, because it shines light on the greater issue, is that when I opened textbooks in history, I never knew who was LGBT. I didn't learn about LGBT environmentalists. And that, to me, showcases like, how far behind we are.

BELTRAN: So what are some ways that the environmental movement might become more inclusive?

HERNANDEZ: If we don't recognize and celebrate diversity in the world around us, we risk losing it all. And as younger generations rally around intersectionality, there's a chance to lay a foundation of new story. And I think for me, that is one way that we really protect queer and trans communities, is that, I'm not asking you to run around with the rainbow flag, I'm asking you, Are your stories inclusive? Are the people that you hire coming from diverse perspectives? Diversity is a threat to uniformity, and uniformity, in the monocultural world that we live in today, allows us to believe this is the only way that works, which is why I think it's hard for a lot of us to let go of that, to say, How do we strengthen our movements?

BELTRAN: And you have an environmental science degree from UC Berkeley. But you've talked about some ways in which environmental education can be exclusionary—it can exclude people. How do you think public spaces like social media can help bridge that gap?

HERNANDEZ: Academic institutions have a role to not just teach us to ask those better questions, but to equip us with the solutions and how to implement them. We shouldn't have waited this long to learn about the concepts around environmental justice, right? I learned it in high school myself, but we should not be adults learning about this, or we should not be learning about the racist history of the conservation movement, in which many of the famous conservationists labeled indigenous communities as "dirty," even though we hail them as our heroes. We could celebrate some of the accomplishments but also recognize what they said was very harmful, and they were never held accountable for it. Environmental education needs to be holistic based on cultural based experiences. Right now, academic institutions don't really offer that. And so I think that social media has really provided a way to provide grassroots education for younger generations. That's a supplement, right? I don't think my platform is the end-all be-all. I think it's a level one education for people who want to be exposed to it, that people want to fall in love with the subject area. Then later, they can take on the classes.

BELTRAN: And on social media, you emphasize the importance of intersectionality. Your username, Queer Brown Vegan, combines three aspects of your identity. Why is it important to you to put yourself out there as a member of all three of these groups?

HERNANDEZ: My username Queer Brown Vegan is funny, it's either met with laughter and love, or people telling me that they're triggered by me and they feel uncomfortable. But anyways, I think the main thing is that Queer Brown Vegan, you know, it's kind of like a semblance to myself, right? One is, as a brown, Latino environmentalist, I am proud to be a Latino. Only around six to seven percent of people who earn an environmental science degree are Latinos. So for me, it's very important for my culture and identity to be representative and to know that we've always been environmentalists. The second thing is about queerness, is that, you know, as someone who came out at 17, right, like, I had to hide my sexual identity in labs, in academic settings. So outside with my friends, they all knew, but within my professors and labs, I kept that away, because I saw that as inferior, or I would hear professors say homophobic and transphobic remarks. And so for me, I had to stay silent, because I said, Well, I don't want to jeopardize my academic opportunities. But then I realized more and more, it's like, why am I comforting people who have the most comfort to make people feel uncomfortable and to oppress people? And so I had to really challenge those dynamics to say, I'm not here saying that I'm trying to wave my rainbow flag at your lab or your institution, I'm just here to say, I need you to respect me as a human being. And the vegan part, just like an, I think an add-on, is that later on, I feel like my beliefs to embrace human and non-human animal liberation through a different lens, that's just part of me. But I think for the Queer Brown Vegan, it really kind of speaks to how intersectional Gen Z is, but also how much we have to offer. I feel like a lot of younger generations get discredited, and we get disempowered, but we actually are much more powerful in the ways that we speak truth to our power.

BELTRAN: And you said that the name Queer Brown Vegan has triggered reactions in people. What have been people's objections to the name?

HERNANDEZ: I think some of the expressions I've gotten is, one, you're not a real environmentalist. The second thing is just people saying, like, That is extremely disrespectful to me. And I'm like, No, no, no, what you just said to me is disrespectful. My name isn't being plastered on your face. It's not being hung on your wall. It's not in your home. So you have the ability to exit if you don't agree. I don't have the ability nor privilege to leave my identity. I don't get to opt out of my queerness. That carries on with me for the rest of my life.

BELTRAN: So right now we're in Pride Month—happy Pride! And it's wonderful to celebrate the queer community and its activism. But in one of your videos, you warn against the idea of rainbow washing. What is that? What does that look like?

HERNANDEZ: I'm happy that it's Pride Month, but I'm also concerned. So the reason why I say that I'm concerned is that rainbow washing is the act when corporations, institutions and organizations celebrate this identity of queer and trans cultures. However, many of these corporations have been linked to having either, A, anti-LGBT donors or anti-LGBT owners of the company, and B, are sourcing and mass-producing Pride merch from different countries that are directly from slave labor. And there's no transparency from the merchandise industry, where those supplies are coming from. So in theory, if I'm celebrating Pride, I'm not just celebrating here in America, I'm celebrating also for my siblings, who are outside in different countries where anti-LGBT laws are way worse. So for me, I think that we have to understand that for LGBT communities that we don't fall victims to the same institutions and corporations that would have us locked up. So now that we're seeing these like large celebrations, I think it's important to ask, like, who's making your Pride merch, and if you know who's making your Pride merch, were they paid an ethical wage? So it's not to say that I'm trying to ruin people's happiness here, I'm saying that, yeah, we can celebrate, you can reuse the old materials, you can go thrift it if you want. But being mindful that our liberation did not just start in America and end in America. We have to connect ourselves to global movements that are also working to liberate themselves. And I think that it's become a bit of a corporatized month.

The term “rainbow-washing”, sometimes known as “pinkwashing,” refers to corporations selling rainbow-themed merchandise or otherwise promoting Pride without taking significant action to support LGBTQ+ people, or while supporting policies or receiving money from groups that harm queer communities. (Photo: Thomas Hawk, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

BELTRAN: What sort of connections have you made with your audience?

HERNANDEZ: I don't know how to explain it, but I think a lot of people are always so comfortable to tell me a lot of personal things in my DMs about what they're going through with climate anxiety. A lot of them have fear for the future, whether that's moms that are reaching out asking for like products for their kids, or that they don't know how to talk about it to their husband or their children, or whether that's young people telling me that they need help in their undergrad career, because they don't see anyone that looks like them. I think my space has always been like a couch. It's like a lounge. It's like there's no expectations for you to show up a certain way. I will take you in and like you can hang out. And then when you're ready, you can leave, there's no pressure. So I've always really built my space to be reflective of how I navigated the world, is that it was very tough for me. And I know how tough the system is that we live in today. And so I want to provide that comforting experience for people that they can feel home, that they can feel this sense of identity within themselves or a value being shared. And that they can empower themselves through media and education and to know that they aren't powerless, that they have more than enough information, that they can show these to their professors and challenge them. I think that's the main goal of my work, giving people that space to embrace their thought, because I know how it feels to, to be disempowered and to think you're never good enough for these spaces.

CURWOOD: That’s “Queer Brown Vegan” media creative Isaias Hernandez, speaking with Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran.

Related links:

- Learn more about Isaias Hernandez and his Queer Brown Vegan platform here

- Inside Higher Ed | ”On the Stubborn Whiteness of Environmentalism”

- Built In | “Rainbow Washing: What It Is and How to Avoid It”

[MUSIC: Irma Thomas, “Second Line Medley: I Done Got Over/Ike Ike/Hey Pockey Way” on A Celebration Of New Orleans Music, by Kador/Traditional/Neville Porter-Modeliste Nocentelli, Rhinelander, Rounder Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up, Black hair and the story of a pioneering Black woman a century ago. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Brother Robert/Jeff Hill/Bill Dobrow, “Three Dozen Roses” on Paris To Cuba, by Mario Grigorov, self-published]

Roots of Black Hair Care

Madam C.J. Walker is considered the first female self-made millionaire in the United States, due to her well-documented wealth she earned from her cosmetics and haircare products. (Photo: Scurlock Studios, Smithsonian Institution, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Whether you rock a full Afro, a sleek bob or an undercut, the way you style your hair can help you feel confident and express your identity and culture. And it can be complicated for Black people whose hair tends to grow in tight curls. Centuries of racism have contributed to a Euro-centric beauty standard that elevates straight over coiled hair.

JAMES-TODD: As my daughter often would say, when she was little, we have out-hair, like, the way that our hair is a crown, it grows out of our heads, but really, that becoming not the desirable way to operate in society, and down-hair being valued and out-hair being not valued, kind of the three-year-old terms of “out” and “down.”

CURWOOD: That’s Tamarra James-Todd, an epidemiologist at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Her research focuses on some of the hair care products Black women use to respond to the social pressures to straighten their hair, risking their health with exposure to hormone-disrupting chemicals.

JAMES-TODD: As a Black woman, like many others, we’ll go to beauty supply stores or to our local pharmacy and get our products. And we are often looking for things that say something like, “will make our hair grow,” or “will make our hair fuller” or whatever, like whatever thing or attribute we equate with being beautiful that we also equate with “this works,” whatever “works” means for us. But what struck me was also that the ingredients saying that they were hormonally active, and I was working in a lab, a breast cancer lab, where hormonal activity was linked to breast cancer. I kind of had this aha moment where I said, is there something to this?

CURWOOD: Cancer-causing formaldehyde is also an ingredient in some hair relaxers and straighteners used primarily by Black women. Amid the growing concerns about health impacts, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration is giving its regulations a makeover. The FDA has signaled plans to ban formaldehyde-related chemicals from some hair products as part of efforts to modernize cosmetic regulations. There are at least ten thousand different ingredients used in cosmetics on the market today, but it wasn’t always like this. In the early 1900s, an enterprising Black woman used just a few ingredients in her hair products to make a huge impact and created jobs and uplifted political engagement. Her name was Madam C. J. Walker, and she made a fortune selling her hair products, making her the first American woman, Black or white, to become a self-made millionaire. Joining me now is the great-great-granddaughter of Madam C.J. Walker, A’Lelia Bundles, the author of the 2001 book On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker. Hi A’Lelia and welcome to the show.

A’Lelia Bundles is the author of On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker, now published as Self Made. (Photo: CSUF Photos, Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

WALKER: Delighted to be with you!

CURWOOD: So who was Madam C. J. Walker and what does she mean, writ large, to Black hair care?

WALKER: Madam C. J. Walker was an amazing American business story. Born Sarah Breedlove, the first child in her family born free in Delta, Louisiana in 1867. But by the time she died in 1919, at age 51, she had founded the Madam C. J. Walker manufacturing company, become a millionaire, employed thousands of Black women, empowered them to become economically independent, and used her wealth and influence as a patron of the arts and a political activist. But she really is one of the godmothers of the modern haircare industry, along with other giants of hair care among Black women, but she really created a company that has some enduring legacy.

CURWOOD: When did you become aware of your family's haircare history?

WALKER: So I would say, and not so much the haircare part, but when I became aware of Madam C. J. Walker and her daughter, A'Lelia Walker, who was a key part of the Harlem Renaissance, was really before I could read, when my mother and I would visit my grandfather in the apartment that, where my grandmother had lived before her death, seven years before my birth, but we would go to that apartment. And while my mother and her father talked in the living room, I would go into my grandmother's bedroom and open the dresser drawers, and I found things that had belonged to Madam Walker, A'Lelia Walker and my grandmother May. So, ostrich feather fans, and mother-of-pearl opera glasses and souvenirs from Egypt. So I was beginning to learn something about them even as a toddler. The silverware that we used every day had Madam Walker's monogram, and our china for special occasions had been at Madam Walker's mansion, Villa Lewaro, in Irvington, New York. So I had touchstones with these women. I, my mom was Vice President of the Madam C. J. Walker manufacturing company when I was growing up. So I would go with her to her office in downtown Indianapolis, go upstairs on the fourth floor and play on her typewriter and her adding machine, before computers and calculators [LAUGHS] and then walk to the factory when she would talk with the ladies who were still mixing the Walker products by hand. So that's in the 1950s and early 1960s. So I had a sense of my mother being a business woman and this being her family.

CURWOOD: So, tell me, what were the main ingredients of your great-great-grandmother's haircare formula?

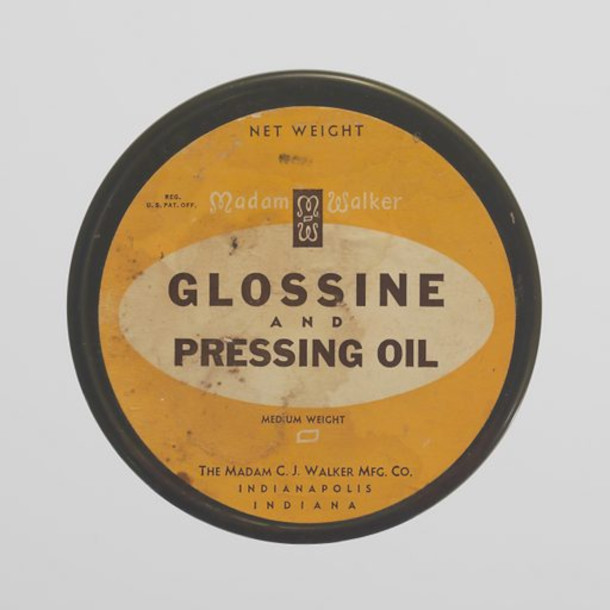

WALKER: You know, it's something very simple, but that we take things for granted now. And to just kind of set the stage, when she started her company in 1906, most Americans didn't have indoor plumbing or electricity. So hygiene was very different. And like many other women, she was losing her hair not just because of really serious dandruff, but because of serious scalp infections. And so the formula for the Walker method was a vegetable shampoo that was less harsh than some of the lye shampoos and soaps. Wash your hair more often, get your scalp clean, and then apply an ointment that was a petrolatum base like Vaseline, that included sulfur, which is a centuries-old remedy for healing skin and scalp infections. Products like Cuticura were actually already on the market. There were other products that used this basic formula, medicinal formula, pharmaceutical formula, but she marketed it and packaged it under her own name.

CURWOOD: Now in recent years, and in the news right now, the conversation is loud about the danger of hair chemicals and Black women's health. What's your reaction to the FDA's recent announcement that agency is stepping in to regulate now the chemicals that women use in their hair?

Madam C. J. Walker’s products were often similar to those already being sold, but her understanding of marketing allowed her business to thrive. (Photo: Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, public domain)

WALKER: I'm glad that this attention is being paid to the harm that chemicals can do. You know, what Madam Walker and her contemporaries developed with petrolatums and petroleum-based and sulfur-based products, you know, now we know that with shampoos, they're sulfate free, that we don't use petroleum based. But during that period of time, that was revolutionary. And sulfur was somewhat harmful, but not in the way that the chemical straighteners that came a couple of generations later, that this hydroxy is, I think, can be very harmful. And I think some of the scientific studies show that.

CURWOOD: So, tell me as a Black woman, as a writer, journalist, historian, talk to us about the emotional and psychological ties between Black women's sense of self and their hair in modern America.

WALKER: So much of this is how we see ourselves, what our self-image [is], how we present ourselves to the world. And a lot of the way that we feel about ourselves depends on the messages that come from the people who are closest to us. Though sometimes, I do have friends who wear their hair natural, whose daughters really want to wear lace front wigs, or they really want to straighten their hair, they don't want to do what mama did! But we, I think there is a journey, at least for myself, personally, that many of us go through in terms of becoming comfortable with who we are. And that's not to say that, you know, some people, especially I think young women and teenagers, want to change their hair every other week. And I think they ought to have the freedom to do that. But I personally, like to be able to wear my hair without any extra, without any extra things, without extensions. That's just me. But I kind of admire the creativity of some of the young women. But I do think it really does have to do with the messages that we get. A couple of examples for me: so when I was growing up, I had very long hair and I was what we would say "tender headed". And my mother was very patient with me, she took a lot of time. And when I would, you know, squirm, she would say, "Oh, you know, sweetie, you're gonna be so pretty when we finish." And that was her way of trying to give me confidence. She bought Black dolls for me. So there was a message there. That did not prevent me from feeling the pressure of the external world. I always went to predominantly white schools. So you begin to compare your hair texture to the hair texture of your classmates. And because of this emphasis on European standards of beauty, I think that many young girls and, you know, women and older women feel this pressure to conform. But if you have a family member or someone close to you, or a boyfriend or a girlfriend, who says, "I would rather your hair be this way than that way," sometimes it's very hard to assert yourself and say, "But you know, this is my hair, this is the way I want to wear it."

CURWOOD: Now, what about the business marketplace? I've heard some Black women say that, if they wear natural hair in the corporate setting, it really sets them back. They don't advance as far and they feel that they have the evidence that straightened hair gets them further than natural hair. What do you think about that?

WALKER: I think that's absolutely true. But you know, my personal experience as a producer and an executive with ABC News, and then having worked with NBC and ABC for 30 years, I watched an evolution of hair. I started at NBC in 1976. And one of the reasons that I chose not to take the on-air route is because I had a big Afro and I did not want somebody telling me how to wear my hair. But behind the scenes, I could wear my hair however I wanted without that kind of pressure. Then through the years as I had different jobs, my last position was as Director of Talent Development at ABC. And so I was working with young correspondents, people who were just coming on board, hiring new employees. And I know that it was very difficult, that people were sort of dismissed if they didn't have straightened hair. But I've noticed within the last sort of decade or so, especially on MSNBC, that the women attorneys, who had natural hair, were brought on the show because they brought some expertise. So I'm coming with my brain, and my hair comes with me. I even noticed that a one of the male hosts on CBS Morning News the other morning had cornrows. So people are pushing that envelope; when you see executives like Debbie Lee or Sheila Johnson or B. Smith, when she was in the public eye with natural hair, or Ursula Burns, it begins to change the equation when somebody at the top has the courage to do that. And it's not even courage, it's like, this is the way my hair grows. So I think we are in a moment where there are people who think they can still intimidate you. And if you're in a place where there are not a lot of eyes on you, and there's not a lot of legal recourse, there are still people who will tell you you cannot wear your hair a certain way. We know that if you're just starting out or if you're in a place where you don't have a lot of power, it's very hard to fight back.

CURWOOD: So, A'Lelia, what inspired you to write the book On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker?

Black women can lower their risk of reproductive cancers by avoiding certain hair straightening products, but natural Black hair is often stigmatized in America. (Photo: Nappy.co, CC0)

WALKER: I was really more interested in A'Lelia Walker than Madam C. J. Walker, because A'Lelia Walker, my great grandmother, Madam Walker's daughter, had known the artists and writers and musicians of the Harlem Renaissance. And my senior year in high school, I, we convinced the school administration to let us have a Black history humanities course. So I wrote about A'Lelia Walker and her Harlem Renaissance friends, and that was my interest. Madam Walker was really complicated for me, because people thought, oh, Madam Walker, isn't she the woman who invented the hot comb? Well, she didn't invent the hot comb, but that was the narrative about her, and I was kind of keeping her at arm's length. So it took me a while to fully understand her many dimensions. And when I got to Columbia and journalism and graduate school, my advisor for my master's paper was Phyllis Garland, the only Black woman on the faculty at that moment when those doors were finally opening up for diverse hires. And Phyl and I sat down to talk about my master's paper topic, and I gave her the kind of cliched, trite topics that students give to their professors. And at the end of the conversation, she said, "Your name is A'Lelia. Do you have any connection to Madam Walker and A'Lelia Walker?" And I'm pretty sure Phyl knew the answer to that question. Her mother had been editor of the Pittsburgh Courier, she had worked for Jet and Ebony. But I wasn't walking around talking about my relationship to them. So when I said, "Why, yes, that's my family," she said, "That's what you're going to write about." So it was really the power of a professor who understood the importance of that story, who validated it for me, and who really set me on a path that's really kind of five decades old, almost.

CURWOOD: So what was the story you tried to tell in On Her Own Ground?

WALKER: I wanted people to know about Madam Walker's many dimensions, because she had such good instincts about hiring her executive team that they created, they saved the records. So we have literally 40,000 documents and photographs that were donated to the Indiana Historical Society that have been digitized. So I had incredible, an incredible foundation for my research. And then I spent many years reading other manuscript collections and newspapers and doing research. So after I had done this research, I realized, yes, she had founded a haircare company, that was very important. Yes, she had become a millionaire. But what intrigued me was the jobs that she created for thousands of Black women who otherwise would have been maids and laundresses and sharecroppers; allowed them to become economically independent, to buy homes, to buy real estate, to educate their children, but also empowered them to become leaders in their communities. So that was fascinating to me, that she based it on the things she learned from the women of her church, the St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal Church, from the women in the club movement, that leadership was important. I loved learning that she had been politically active. She was a, she was a political radical [LAUGHS] which just, you know, amazed me and made me feel good that during World War One, she spoke out against lynching, she spoke out on behalf of Black soldiers. She was even spied upon by a Black spy who was working for the War Department and, along with Ida B. Wells, was called a "Negro Subversive," which is like the Nixon's enemies list. So I wanted to show those many dimensions and the impact that she continues to have, to inspire entrepreneurs, but also to inspire people to not only become wealthy and influential but to use that wealth and influence in a political way and to support the arts.

CURWOOD: Before you go, A'Lelia, tell me: what is Madam C. J. Walker's legacy?

WALKER: For me, Madam C. J. Walker's legacy is one of empowering women and one of inspiring women. She really does show us the possibilities of what can happen both when women have confidence, but also when they have leadership and they can make a difference in their community. One of my favorite things, as I've done all this research, is something that Tiffany Gill, a friend of mine who's a historian, discovered when she was doing her dissertation, and she was looking at women in the Civil Rights Movement, in particular beauticians during the Civil Rights Movement. And what she learned is that beauticians, women who were members of the National Beauty Culturists' League, that they were very politically active. I think some of those seeds were planted by Madam Walker in that 1970 convention. And those beauticians would invite Martin Luther King to their conference, their convention every year, and they helped pay for the buses that took people to the March on Washington in 1963. It's significant to know that A. Philip Randolph's wife, Lucille Green Randolph, was a Walker agent. So I love this mix of women who are economically independent, own their own businesses, being leaders and being able to use that for social justice.

CURWOOD: What else would you like us to know?

WALKER: We can twist ourselves into knots trying to look like somebody else. And I think it is, there's a lot of reckoning that is important for women to do in terms of how we feel about ourselves. I know that for me, personally, I've had a long haircare journey, for 70-plus years. It's taken me a while to be comfortable with myself and to realize that my hair texture has all my ancestors, as does the person sitting next to me have all her ancestors, and what I can do with my hair is not what you can do with your hair, that it's so important for us to love ourselves. And that's, that's really for me, the most important part of a haircare journey, is what is it that we do that makes us feel good about ourselves and love ourselves?

CURWOOD: A'Lelia Bundles is the great-great granddaughter of Madam C. J. Walker. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

WALKER: Totally my pleasure.

A’Lelia Bundles is the great-great-granddaughter of Madam C.J. Walker. (Photo: Courtesy of A’Lelia Bundles)

Related links:

- Learn more about A’Lelia Bundles

- Purchase A’Lelia Bundles book and support both Living on Earth and local bookstores

- A’Lelia Bundles is the brand historian for MADAM, a new line of haircare products inspired by Madam C.J. Walker. Explore them here.

- Listen to our previous story on the risks of certain Black haircare products

[MUSIC: Oscar Peterson Trio, “I Got It Bad And That Ain’t Good” on Night Train (Expanded Edition), The Verve Music Group.]

CURWOOD: Next week on Living on Earth, we’ll celebrate Juneteenth with stories of heroes from history. Also, we’ll hear about efforts today to liberate Black Americans from the toxic burdens of environmental racism. Celebrating Juneteenth and modern liberation from environmental injustice, next time on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Oscar Peterson Trio, “I Got It Bad And That Ain’t Good” on Night Train (Expanded Edition), The Verve Music Group.]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Shanzay Asif, Paloma Beltran, Josh Croom, Jenni Doering, Karen Elterman, Swayam Gagneja, Sommer Heyman, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Allison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at LoE.org, Apple Podcasts and YouTube Music, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments@loe.org. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth