July 5, 2024

Air Date: July 5, 2024

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

SCOTUS Restricts Rulemaking

View the page for this story

In a 6-3 decision the US Supreme Court struck down the longstanding Chevron deference doctrine, which allowed federal agencies to make rules relying on unclear statutes, provided their interpretation was reasonable. Law professor and former EPA Regional Counsel Pat Parenteau joins Host Aynsley O’Neill to parse the potentially disastrous consequences of this decision for environmental and other public protection regulations and what agencies and lawyers will need to do to have a fighting chance in court. (14:47)

From the History Books

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Living on Earth Contributor Peter Dykstra and Host Aynsley O’Neill celebrate the birthday of Buckminster Fuller, inventor of the geodesic dome and other engineering marvels aimed at improving energy efficiency. They also look back to President Nixon’s proposal to create two new federal agencies consolidating US work on environmental regulation as well as on oceans, atmosphere, and weather, giving rise to the EPA and NOAA. (02:50)

A Vivid New View of Earth

View the page for this story

A powerful new NASA satellite called PACE can look at the ocean and clouds to distinguish between different kinds of microscopic phytoplankton and aerosols from an orbit 400 miles up. PACE Project Scientist Dr. Jeremy Werdell joins Host Jenni Doering to describe how the technology works, its value to scientific research on climate change, and the real-time data it provides about water and air quality worldwide. (09:21)

Starborn: How the Stars Made Us

View the page for this story

Stargazing has profoundly shaped who we are as human beings, and gave rise to science, religion, and origin stories from diverse traditions. Roberto Trotta, a cosmologist at the International School for Advanced Studies in Trieste, Italy, explores this legacy in his book Starborn: How the Stars Made Us (And Who We Would Be Without Them). He joins Host Jenni Doering to discuss how studying the night sky shaped science and more and why satellites now threaten our connection to the stars. (16:53)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

240705 Transcript

HOSTS: Jenni Doering, Aynsley O’Neill

GUESTS: Pat Parenteau, Roberto Trotta, Jeremy Werdell

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

DOERING: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

DOERING: I’m Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

A new satellite gives NASA a full-color view of the planet.

WERDELL: We always call it the blue marble but the reality is the ocean is a spectrum of color. With PACE, we now have all the colors of the rainbow, a continuous spectrum from the ultraviolet, the purples, all the way into the reds, and by looking at all the greens for example, suddenly these little differences are standing out.

DOERING: Also, how stargazing led to huge leaps for humankind.

TROTTA: Astronomy had this very long tradition of data observation, interest for the sky, out of which quantitative science and physics sprang. Without astronomy, Newton wouldn't have written down the laws of gravitation, and physics would not exist as we know it. And without physics, none of the other sciences.

DOERING: Those stories and more, this week on Living on Earth—stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

SCOTUS Restricts Rulemaking

On June 28, 2024, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down a decades-old Chevron Deference Doctrine that had mandated federal courts to accept reasonable agency interpretations of unclear laws. (Photo: Joe Ravi, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

DOERING: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

After the November general election, it’s possible the White House will change hands, but federal judges are appointed for life. And the six justices who are on the Supreme Court thanks to Republican presidents are overturning decades of precedent on abortion, presidential power, and environmental law. With one of the last decisions released this term, the Court struck down the Chevron deference doctrine, significantly curtailing the power of federal agencies to interpret the laws that they regulate. In two cases known as Loper and Relentless, fishing companies challenged a rule by the National Marine Fisheries Service, arguing that they should not have to pay for the federal monitors that may be assigned to observe their fishing vessels. But there are far broader implications of overturning the Chevron doctrine than for just a fishing company or two. For more, we turn now to Pat Parenteau, former EPA regional counsel and emeritus professor at Vermont Law and Graduate School. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Pat!

PARENTEAU: Thanks. Aynsley, good to be with you,

O'NEILL: Pat, please walk us through the history of this Chevron deference case.

PARENTEAU: Sure. So, this is a 40 year old precedent. In a decision by the Supreme Court in 1984. Chevron vs. Natural Resources Defense Council is the technical name of the case. It held that when an agency is interpreting a statute, and the language of the statute is unclear or ambiguous, that so long as the agency's interpretation is reasonable, it must be upheld. So we call this the Chevron deference doctrine. It has been cited 19,000 times over the 40 year history of this doctrine. So as Justice Kagan said in her dissent, in this case, we're going to be discussing, this has become a cornerstone of administrative law. It isn't just EPA rules. It's all the rules of the federal government are governed by this standard that we've had. And now as we'll discuss the new world that we're facing, because the Supreme Court has overturned the chevron decision.

“Chevron is overruled. Courts must exercise their independent judgment in deciding whether an agency has acted within its statutory authority,” said Chief Justice John Roberts during the ruling. (Photo: J.Marca Executive, Flickr, Public Domain)

O'NEILL: And now, it was overruled in a 6-3 split. Why is that? What arguments did the justices give in that ruling?

PARENTEAU: So Chief Justice Roberts wrote the majority opinion, yes, it was 6 to 3. So it was another one of these partisan splits that we've become familiar with on the Supreme Court with six Republican appointed justices agreeing and the three democratically appointed justices, sometimes referred to as the liberal wing of the court, in dissent. Chief Justice Roberts basically said the Chevron decision was wrong from the beginning. And it hasn't been workable, at least in his view. And it was wrong he said, because another statute, the Administrative Procedure Act, which sort of governs the way agencies operate, and it also governs the way courts review agency decisions. Chief Justice Roberts' view, the APA was a clear command, that the courts must always be the ones to decide what the law means, even though agencies have a lot of expertise, obviously, scientific expertise, technological expertise, policy judgment. Even though many of these questions contain a rich mixture of fact, and policy and science and so forth. In the end, said, Chief Justice Roberts, it's always going to come down to a legal question. And only the courts should be deciding what the answer to those legal questions would be.

The ruling significantly reduces the authority of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) among other federal agencies to interpret and implement the laws they are charged with enforcing. [Note: The above picture is from EPA Union rallies in 2018]. (Photo: AFGE, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

O'NEILL: Who have been the stakeholders involved throughout this SCOTUS case?

PARENTEAU: Yes. So in the case that was just decided, it's called Loper and a companion case, which goes by the name of Relentless. The point is, this particular case dealt with the fishing industry. So when you ask who the players are, it's typically an industry group that is subject to a regulation they don't like and they want thrown out. Sometimes it's the mining industry, sometimes it's the fossil fuel industry, could be any number of other industries could be landowners could be real estate developers. The point is these are all interests who have been subject to regulations, which they find opposition to. And now what we see is that those economic interests have been joined by Republicans, attorneys general, Republican governors, and it sounds partisan, but that's because it is partisan. The Republican governed states have uniformly challenged the Biden administration, and before that the Obama administration and have been trying to get the Supreme Court to rule that these agencies adopting these regulations they find objectionable, shouldn't get deference. And so they have now finally succeeded in that mission.

A moment of public demonstration on abortion rights in front of the Supreme Court leading up to the 2022 Dobbs decision overturning Roe v. Wade. (Photo: Mark Waner, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

O'NEILL: And what do you expect are going to be some of the acts or laws that are going to be challenged now that the Chevron Doctrine has been overturned?

PARENTEAU: Honestly, everything is going to be subject to challenge. We're seeing virtually every rule that the Biden administration has adopted, clean air, clean water, climate change, endangered species, National Environmental Policy Act, all of them have been challenged. And so this opinion from the Supreme Court is going to greatly strengthen the arguments of people challenging these rules: protecting public health, protecting endangered species, whatever they might be attempting to do. And it's not clear that the opponents to these rules are going to win every single time. But their arguments have been greatly strengthened when the Supreme Court has basically said, it's up to all of the individual judges out there. And there are more than 500 Federal Court judges in the United States. So, it's a large number over 200 were appointed by former President Trump. So you know, they're very conservative. And so you have a mix of judges in the lower courts that are now charged with interpreting statutes in a way that they haven't for 40 years. So that's going to create some chaos. Chief Justice Roberts tried to make the case that his decision was going to bring some predictability and some stability to interpretations of statutes. I don't think that's right. You know, we heard the same thing when the Supreme Court overturned Roe versus Wade, that that was going to be the end of the Supreme Court getting into the abortion debate, right. And look where we are today. More and more cases are coming up. So this business of saying we're going to overturn a long standing precedent, and we will clarify the law simply hasn't borne out. So what I think is going to happen is you're going to see conflict, in the ways that the lower courts are trying to figure out what their new responsibility is. It used to be, as long as the agency had prepared a complete, rigorous, even administrative record to support their decision. And as long as the Court said, even though there's more than one way to interpret this law, the way that you've interpreted it is reasonable. It isn't arbitrary. People can differ. But somebody's got to decide. So what all of these cases come down to is that question, who decides when a law isn't crystal clear.

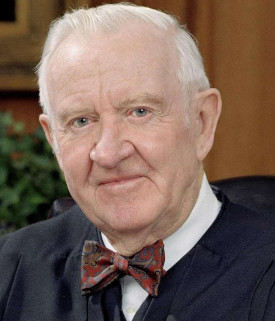

The author of the Chevron Deference ruling that The Supreme Court recently overturned, John Paul Stevens, died on July 16th, 2019. The Chevron Doctrine has been cited 19,000 times over its 40-year history. (Photo: Steve Petteway, Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States, public domain)

And I don't have to tell you that laws typically are not always crystal clear. When Congress adopts a law, it doesn't adopt a vague statute on purpose. But sometimes, in order to get something passed, you have to compromise.Which means sometimes the language of a law is left a little bit vague to allow the expert agencies, EPA and others to basically figure out how do we do what Congress has ordered us to do? How do we protect public health? How do we keep the air clean, the water clean, and so forth? And so Congress has in for a long time now been delegating this broader authority to agencies and relying on the agencies to figure out what's the most sensible way to achieve the statutory purposes. This new regime that we've been given with the Loper decision overruling Chevron is no judges are not necessarily going to be persuaded by what the agencies have done. Even if it looks reasonable. That's not enough anymore, for it to be reasonable.

O'NEILL: With such broad implications, what are the options that people are looking into when it comes to challenging this recent decision?

PARENTEAU: Yeah, we have to accept the fact that this is the law of the land, right? So those of us that are concerned about the environment and public health and climate and all the rest, are going to have to figure out how to deal with it. And here's some ideas: Number 1, when the court says that they're no longer going to give deference to agencies interpretation: that cuts both ways, doesn't it? So if there's a second Trump administration, we know what we're going to see, we're going to see another rollback of all the environmental rules that the Biden administration has been adopting. So then the question is, there'll be people challenging those rules. And, so this decision is going to mean, those attempts to roll back rules that are on the books by coming up with a new interpretation of the governing law. They're not entitled to deference either. So I'm not as optimistic about how that's going to work out. But certainly the argument is going to be there. There's a saying that we use in the law "What's sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander."

The Supreme Court decision to overturn the #ChevronDoctrine could present challenges for implementing and enforcing laws that support nature. We will continue to work at all levels of government to protect people and our planet. https://t.co/b4V8md9STA

— The Nature Conservancy (@nature_org) June 28, 2024

And what that basically means is, if we the environmental proponents of certain rules don't deserve deference, or those rules don't deserve deference, then the same is true of rules that are trying to deregulate. The other thing I'll say is that there are some things in Chief Justice Roberts opinion that we can use to defend the rules that we want to see upheld. He makes a point in referring to an earlier Supreme Court decision, which we call the Skidmore decision. And this decision also deals with when do agencies deserve deference when they're interpreting a statute. And the way this works is Skidmore deference, as we call it, as opposed to Chevron deference which is automatic. It relies on the ability of the agency to basically persuade the court that its interpretation is, quote, “the best reading of the text of the statute”. Looking at the structure of the statute, the purpose, the history, has the agency come up with an interpretation, which the court can accept, as quote "the best reading”. So I think agencies, lawyers, and environmental lawyers in general that want to see these rules upheld, are going to have to work harder at establishing through the administrative record that supports these rules through the rulemaking process itself. And through the way that they explain the basis in the statute for the rule, and go through very carefully how they've looked at every single factor that should be looked at and how they've explained clearly the choices that they made, based on the information that they have, using the best available science and so forth, right. So I think there's hope that if we do a really good job of building a case and a record to support interpretations that further environmental law, at least we’ll have a fighting chance to prevail when we're in court.

O'NEILL: Pat, you've been working in this sphere for a very long time at this point. Now, what do you make of a decision like this?

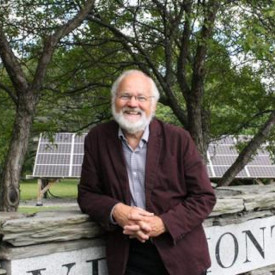

Pat Parenteau is emeritus professor of law at Vermont Law and Graduate School and formerly served as EPA Regional Counsel. (Photo: Courtesy of Vermont Law and Graduate School)

PARENTEAU: Somebody like myself has been doing this for over 50 years, it's soul crushing. You're watching your life's work get trashed for reasons that don't make sense. It's not as if environmental regulation has caused economic harm. Quite the contrary. All the studies show that environmental regulations create more economic benefit than they do economic costs, the benefits of these regulations, whether they're health or environmental quality, and be able to drink your water and know that somebody's paying attention to what's in that water. And over the course of my career, what I've seen is environmental law doing what it was intended to do, which was make life better, make the quality of people's communities better. And to see that taken apart piece by piece is awfully difficult. But you know, keep trying. There's no really alternative. You can't quit. There's no quitting in this kind of a challenge. You just have to find ways of making progress wherever you can, keep making the arguments, keep doing the research, keep advancing the right values, and try to galvanize people so that they don't just accept what's happening as inevitable. Because it isn't inevitable. We still do as a nation, as a body politic, we still do control our own destiny, but only if we take responsibility and act on it.

O'NEILL: Pat Parenteau is former EPA Regional Council and Emeritus professor at Vermont Law and Graduate school. Thank you, as always, Pat for joining us.

PARENTEAU: Thanks, Aynsley.

Related links:

- Read the Court’s full opinion

- Read more about the ruling

- Learn more about Pat Parenteau

[MUSIC: Alison Brown Quartet, “Without Anastasia’ on Alison Brown Quartet, by Alison Brown, Vanguard Records]

DOERING: Coming up, keeping tabs on the health of the planet with eyes in the sky. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Philip Boulding, “Ohana Kai (Family of the Sea)” on Musings, by Philip Boulding, Magic Hill Music, BMI]

From the History Books

The geodesic dome at Montreal’s Biosphere Museum was designed by Buckminster Fuller, a futurist who aimed to do “more with less.” (Photo: Daniel Mennerich, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering

O'NEILL: And I'm Aynsley O'Neill.

It's the time in our show where we give a call to Peter Dykstra. He's the Living on Earth contributor who brings us stories from the history books. And he's on the line now from Atlanta, Georgia. Hi there, Peter. What do you have for me this week?

Buckminster Fuller, coiner of the phrase “Spaceship Earth”, in 1972. (Photo: Dan Lindsay, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 3.0)

DYKSTRA: Hi, Aynsley. We'll start with a birthday of a giant in the fields of science and environment. Back on July 12th 1895, the futurist R. Buckminster Fuller was born in Milton, Massachusetts. He developed the geodesic dome, and other structures intended to make construction less costly and more energy efficient. He was fond of doing more with less. He also toyed with more energy efficient cars, exhibited them at the World's Fair in Chicago in the 30s. And on the personal side, he got thrown out of Harvard, not once but twice, and was a World War I veteran. In a novel attempt at improving science communication, he converted some of his lectures into verse. And because of that, he was appointed to a poetry professorship at Harvard, the same school that threw him out twice.

O'NEILL: Okay, wow. When I was in school, I used to rewrite song lyrics to be about, you know, photosynthesis or the dustbowl or whatever, as a study technique. It's nice to know that there's a rich history behind that, all right.

DYKSTRA: A rich history, but it didn't get you to a professorship at Harvard, I'm sorry.

O'NEILL: It didn't, but I can give a great rendition of just Dust Bowl-ian Rhapsody whenever we get the rights.

DYKSTRA: I look forward to hearing it.

O'NEILL: All right, Peter, what else do you have for me this week?

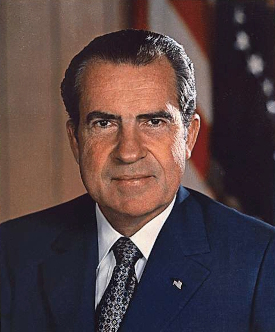

In July 1970, President Richard M. Nixon proposed the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). (Photo: Rupert Colley, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Another July anniversary, July 1970, when the US President Richard M. Nixon proposed two new federal agencies to consolidate US work on environmental regulation, as well as on oceans, atmosphere, and weather. Within the year, the EPA, the Environmental Protection Agency, and NOAA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, were both in business.

O'NEILL: And now almost 55 years later, those agencies are kind of the bread and butter of environmental policy in the United States. It's a little strange to think that they didn't exist before then, actually.

DYKSTRA: And also a little strange to think that they added to the unlikely environmental reputation of Nixon.

O'NEILL: All right, well, thanks as always for bringing us these stories, Peter. Peter Dykstra is a Living on Earth contributor and we will talk to you again soon.

DYKSTRA: Aynsley, thanks a lot and we'll talk to you soon.

O'NEILL: And there's more on these stories at the Living on Earth website, loe dot org.

Related links:

- Buckminster Fuller Institute | “About Fuller”

- More on the founding of the EPA and NOAA

[MUSIC: Vagelis Boudounis, Maro Razi, “Yellow Submarine – Instrumental” on Let it Beatles, Melody Maker]

O’NEILL: The outcome of the 2024 US presidential election could profoundly shape the future of the climate and environment both at home and around the globe. And there are important down-ballot races and ballot measures too. Here at Living on Earth we are working hard to give you the stories and information you need to make your decisions on election day. So, what issues are you most interested in having us cover? Let us know by sending us a written or audio message at comments@loe.org.You can use the Voice Memos app on the iPhone, the Voice Recorder app on an Android device, or any similar app to record your message and then email it. And, we might just include your voice on air! Just be sure to give us a daytime phone number to reach you so we can verify your submission. So, email us, at comments@loe.org!

[MUSIC: Vagelis Boudounis, Maro Razi, “Yellow Submarine – Instrumental” on Let it Beatles, Melody Maker]

A Vivid New View of Earth

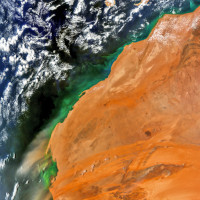

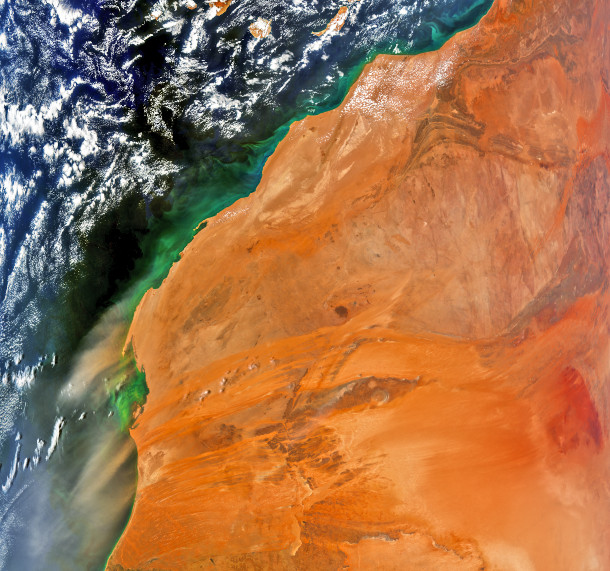

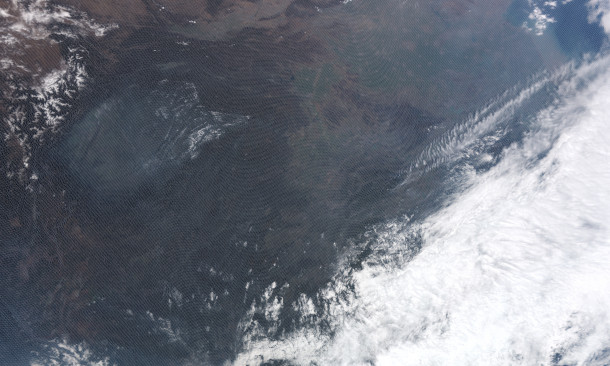

This image encompasses all of the letters in the PACE acronym. Blooms of phytoplankton (P) are seen as green colors off the coast. Red dust aerosols (A) blow from western Africa over the Atlantic Ocean that is dotted with clouds (C). Minerals carried within the dust deliver key nutrients such as iron to sustain life at the base of the ocean ecosystem (E). (Photo: NASA)

DOERING: A new NASA satellite known as PACE is now collecting and beaming back vital insights on the health of our planet. The PACE mission launched in February of 2024 and is designed to gather data about Earth’s oceans and atmosphere. From an orbit 400 miles up, the sophisticated instruments on this spacecraft can even see microscopic phytoplankton and aerosols. That gives scientists a detailed view of harmful algal blooms and air pollution, in real time. Dr. Jeremy Werdell is an Oceanographer in the Ocean Ecology Lab at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center and the Project Scientist for the PACE mission. Dr. Werdell, welcome to Living on Earth!

WERDELL: Thank you so much. I'm really happy to be here.

DOERING: So how are you actually able to see and distinguish between different kinds of tiny particles? I mean, we're talking about like miniscule microscopic phytoplankton, aerosols that are also super tiny. And you're doing this from space.

WERDELL: It's my favorite question. And when I get to do this in like a public setting, like a bar, I love being able to walk in and be like, yeah, I can see invisible stuff in the ocean from 400 miles above the sea surface.

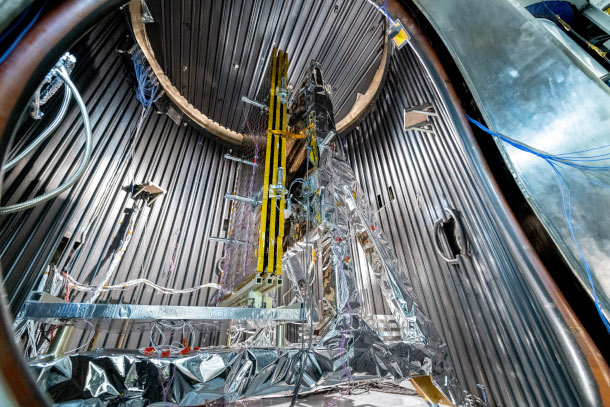

The NASA PACE mission launched in February 2024. (Photo: NASA)

DOERING: Wow.

WERDELL: It all really relates to color. The instruments we have, in many ways operate just like your eyes do. I mean, when we refer, you know, to a space based view of the ocean, you know, if you think about those beautiful pictures from International Space Station, it's the blue marble, we always call it the blue marble. But the reality is the ocean is a spectrum of color. And there are photosynthetic pigments within phytoplankton that absorb different kinds of green and blue light. So really, there are almost like 150 different shades of green. And so when we have these--

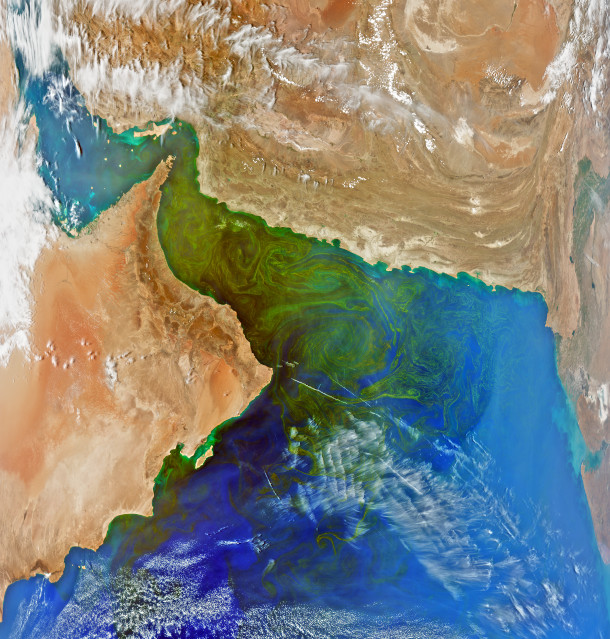

For decades, massive phytoplankton blooms have occurred during the winter in the Gulf of Oman. The swirling bands of green seen here may be caused by a phytoplankton type identified by earlier in-water studies: a dinoflagellate known as Noctiluca scintillans. (Photo: NASA)

DOERING: Woah, what?

WERDELL: Yeah, exactly. Think about like walking through the forest, you might not know what every different cluster of trees is. But the little subtleties in the greens and the shapes tell you, hey, this species, this plant is different than the other one. So you can start seeing subtle differences simply by looking at color. And where we have this beautiful new mission come in is this brilliant fleet of Earth, observing systems NASA and others have had for years, they only measure two greens, they only measure two blues, for example. And that is enough information to say, hey, I see a phytoplankton signature in a backdrop of everything else that might be in the ocean. But it's just saying, hey, I see phytoplankton there. With PACE, we now have all the colors of the rainbow, a continuous spectrum from the ultraviolet, the purples, all the way into the reds. And by looking at all the greens, for example, suddenly, these little differences are standing out. And from that, you can start saying, hey, I think there's a phytoplankton community there that is different than the one, you know, in this other body of water. So while there have been other missions that have done this previously, they've done it kind of on small scales, either they don't see the entire globe or they turn on and off. So with the primary instrument on PACE, it's the first time we will see the entire globe every day in this full spectrum of color.

The mechanical team assembles in the clean room where they prepared the PACE Observatory before launch. (Photo: NASA)

DOERING: I mean, it almost sounds like what you're describing is like we were colorblind. And now all of a sudden, the world is full of different colors.

WERDELL: I'm gonna steal that, that's perfect.

DOERING: Oh, okay!

WERDELL: Thank you, Jenni. It's so much information that we're talking about, like thousands of unique pieces of information in a five by five kilometer box.

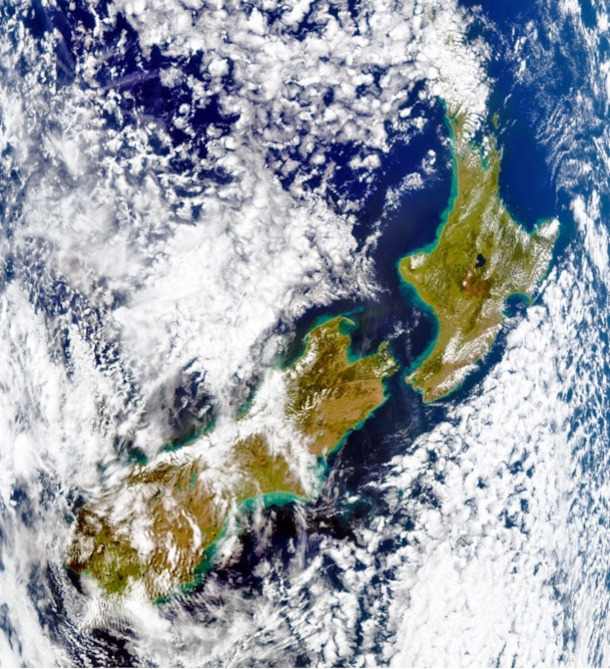

New Zealand's North Island and South Island each have bright blue-green "outlines" in this image. This may be caused by sediment being re-suspended from the ocean floor by the action of waves and tides. In some places, such action can stir up nutrients from the ocean depths, fueling populations of tiny algae that form the base of the marine food web, known as phytoplankton. (Photo: NASA)

DOERING: And why should we care about this data? How might this information be used by the public?

WERDELL: So one of my favorite things about PACE is that it provides information that's useful on multiple timescales, and I'll focus on two. If you're thinking really near term, let's say you're not in view of the ocean, so you don't really spend a lot of time thinking about phytoplankton or biology in the ocean, that's microscopic. You still care. They form the base of the food chain. And so the food we eat comes from phytoplankton. And even if you're not a seafood connoisseur, or fan, perhaps you travel to the beach for recreation, or you know people whose livelihood is based on fishing, or owning a restaurant or hotel near the beach. Well, the ocean and that industry is very connected. So there's a ton of socioeconomic benefit in understanding the ocean. And then of course, you have the harmful species that can contaminate drinking water in bodies of water near water intake in your neighborhood, or shellfish fisheries can be closed because of toxins in the water from phytoplankton. So there are really good short term reasons to be thinking about these things, even if they're not part of your everyday mindset. Then similarly, when you pivot to the atmosphere, air quality, you know, we can inform on air quality. And not every community has the advantage of local networks that measure air quality. So now with these eyes in the sky, you have tools and assets that are free to decision makers and early warning detection systems that tell you about the quality of what you're breathing. And then if you pivot to the generational timescale, we are a climate mission. Aerosols and clouds, they interact. Aerosols are interesting because not only do they influence cloud formation, but some aerosols absorb light, some reflect, so they have different warming and cooling properties. And so if you want to understand how the atmosphere is changing, you have to understand what's in it and how it's changing the heating and cooling properties. Of course, aerosols can land on the ocean and seed phytoplankton blooms. Blooms can release certain gases and compounds that can form clouds. And then thinking on this climate scale of phytoplankton, well, they just move carbon around. Some sink faster than others. So in this conversion of carbon dioxide into organic or particulate matter, where is that all going? How are they responsible in the carbon cycle for moving carbon dioxide around, pulling it out of the atmosphere in the water? So many layers, so many layers, I could go on and on. And I know I already have, with my apologies.

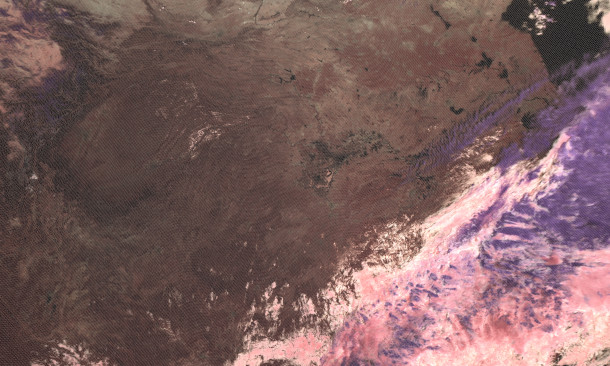

Andrew Sayer, PACE Project Science Lead for Ocean Color Instrument (OCI) Atmospheres, created this and the next image. This first one is a “true-color” version of an image of Southern China. The next image showcases OCI’s unique ability to bring out more scientific details. (Photo: NASA)

DOERING: Lots of layers. And it sounds like a lot of them connect back to each other.

WERDELL: They do. And that's the interoperability and interconnectedness of what we're studying.

DOERING: So how do you actually get this information out to people who could benefit from it? Like, if that's shellfish farmers who need to know about what algal blooms might be near their farms?

WERDELL: That is a great question, because it really does take a village. And in this case, we are very fortunate enough to have an Applications Program baked in to the PACE mission project. And what this group does, is essentially provide the connection to stakeholders. So listening sessions, and really, you know, kind of knocking on doors and going to meetings that, you know, we've never been to before and starting to just spread the word. And if you do that well enough, suddenly, you know, new folks become interested, which creates the second challenge, which is demystifying the use of the data, not just how do I get it? But does it come in a package that I can use easily? And that can range from fitting into a software program to, I just want it to show up on my phone, you know, is there an app? And there are examples of, of how satellite data can be used within an app environment to just give you a stoplight view of your local inland water body, you know, is it experiencing an algal bloom that you may not want to dip your toe in or have your pet swim in, to hey, it's looking clear today.

Even though the “true color” version of this image shows plain white clouds, the OCI reveals that this is a multilayered cloud system. Here, ice clouds and snow are purple, liquid clouds are pink, water is black, barren ground is brown, and vegetated areas are deep red.)

DOERING: Sounds like a weather report for algal blooms almost.

WERDELL: Which would be great. In fact, we have had some really cool interactions over a number of years with shell fisherman on the West Coast and somebody representing fishermen in Maine. And the fact that this kind of information has found its way into those communities is really satisfying for someone like myself.

The PACE spacecraft undergoes final configuration in chamber prior to door closing & Hot Soak; Solar Array engineering test unit Wing Pop and Catch Thermal Vacuum Test. (Photo: NASA)

DOERING: Jeremy, you've been working on this project from the start. What did it feel like to watch the satellite safely launch into space and get up and running?

WERDELL: Jubilation and nausea all at the same time. A mission like this takes about well, PACE took 20 years. So to get to Florida, to Kennedy Space Center and actually see the Falcon nine rocket and the launch pad was profound. And then, of course, we had two weather delays for the launch.

Dr. Jeremy Werdell is an Oceanographer in the Ocean Ecology Lab at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center and the Project Scientist for the PACE mission. (Photo: Courtesy of Jeremy Werdell)

And it's the middle of the night. So it's hard enough staying up and keeping the energy, you know, going, and then you watch the launch. And then you have to wait for roughly a half an hour to make sure that the solar arrays properly deploy and become power positive. And then you can finally breathe. With everything in between, I mean, you're just, you're just numb. But on the far side of that, wow. Just wow.

DOERING: Dr. Jeremy Werdell is an oceanographer in the Ocean Ecology Lab at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, and the Project Scientist for the PACE mission. Thank you so much, Jeremy.

WERDELL: Thank you so much. Love doing this. It's really appreciated.

Related links:

- Read more about the PACE Program

- See more photos from the PACE instruments

- See more photos of the PACE mission

[MUSIC: Nashville Mandolin Ensemble, “Where No Mandolin Has Gone Before” on Plectrasonics, by Alexander Courage/arr.Nashville Mandolin Ensemble, CMH Records]

DOERING: After the break, how stargazing gave us science as we know it.

That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Fred Simon, Bonnie Herman, Liz Cifani, “Time and the River” on Soul Of the Machine-The Windham Hill Sampler Of New Electronic Music, by Fred Simon, Windham Hill Records]

Starborn: How the Stars Made Us

Roberto Trotta often says, “The night sky is humankind's only truly global common, shared by all of us across civilizations and millennia”. (Photo: Daniel Delli, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.0)

O’NEILL: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Aynsley O’Neill

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

If you went to summer camp as a kid, perhaps you slept out under the night sky, the Milky Way spread out like a bright blanket threaded now and then with shooting stars. Stargazing is one of the simple pleasures of life but it’s also profoundly shaped who we are as human beings. Science, religion, and origin stories from diverse traditions have all been deeply connected to the human tendency to gaze up at the night sky. Roberto Trotta is a cosmologist at the International School for Advanced Studies in Trieste, Italy, and he has often wondered what our species might have been like if we had never been able to see the stars. Some planets, like Venus, are eternally shrouded in clouds, so even if intelligent beings had evolved to survive its extreme climate, they would never see the universe beyond. And if our view of the heavens was obscured, Roberto Trotta says it’s possible advanced civilizations capable of traveling out into space would have never developed. His new book is called Starborn: How the Stars Made Us (And Who We Would Be Without Them), and Professor Trotta joins us now. Welcome back to Living on Earth!

DOERING: Thank you, I'm thrilled to be back. So I think we really take for granted the stars that we see at night if we're, you know, lucky enough to have dark enough skies to see those stars. And as you write astronomy was the midwife to all the sciences. Why is that?

TROTTA: Because astronomy was the first of what then become sciences to actually have access to a plethora of quantitative data. That was, of course, in the 16th century when astronomers started working out, our place in the universe, started working out that the earth was not at the center of the solar system, but the sun was, which was, you know, the Copernican Revolution was an absolute paradigm shift of our conception of the universe we live in. But even before then, of course, for millennia, the stars have drawn the attention of humanity, starting from history, as I argue in the book, but also in historical times, we had all these priests and these high sacred people who will look up at the sky, try to divine the future, try to understand what the position and the movement of the planets, and the stars would mean for humanity for the king, for example, for the pyre and so on. The practice of astrology, which is very much disparaged today was very, very important in our past, because it is through astrology, that for thousands of years, humankind kept up their interest for the stars. And we often forget that when the 16th century came around, and a scientific revolution came around, many of the central characters of the scientific revolution, Copernicus, Galileo, the Tycho Brahe, Kepler, they were all astrologers as well as astronomers because the kings and other high place people who paid the salaries, paid the salaries just as much for their observations as for their divination. And so, you know, astrology was very important, and that led to astronomy and astronomy at that point, had this very long tradition of data observation, interests for the sky, after which quantitative science and physics sprang. Without astronomy, Newton wouldn't have written down the laws of gravitation, and physics will not exist as we know it and without physics, none of the other sciences.

A fresco by Giuseppe Bertini of Galileo showing the Doge of Venice how to use the telescope he built in 1609. Galileo’s invention played an important role in advancing our understanding of Earth's place in the cosmos. (Painting: Giuseppe Bertini, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

DOERING: It's so interesting to hear you talk about how something that was so unscientific, you know, especially considering it today, what we know you know, astrology actually did end up leading to careful observation and science itself.

TROTTA: Exactly. And all these patrons who really helped astrology along unwittingly, they also ushered in the scientific revolution eventually.

DOERING: How has our knowledge of time been shaped by the planets and cosmos?

TROTTA: Time is intimately related to the cycles in the sky, let alone the day night alternation that we mentioned, that's, of course, the most basic unit of time. But to go beyond that, to go beyond the simple observing that there is a period of light and a period of darkness that repeats every 24 hours, really, the moon was central the phases of the moon and the lunar cycle of 29.5 days was absolutely crucial in enabling the understanding that we can measure time spans that are longer than a day. And before that was one of the central planks, not just from a point of view, for example of the hunt, we can imagine prehistoric hunters gatherers, trying to time their hands with the full moon, because that's something that we have largely forgotten we never pay any attention to this. But if you are a hunter gatherer in a place in a world that's entirely dark, except for the cosmic luminaries above us, then you absolutely know that when the sun sets on the full moon night, that's when the moon rises. And that means that if you're still hunting prey out at dusk, out at sunset, the moon will follow up and illuminate the hunt, and will stay on for the whole night if needs be, and you can hunt down that prey that has perhaps escaped you. So probably the full moon was enabled not just the most fruitful hunts in prehistory, but also was giving rise to rituals for perhaps certain key rituals to celebrate that successful hunt. So timekeeping, as marked by the period of the Moon was absolutely central. And of course, even today, when we glance at the 12 subdivisions of a normal clock, we are without realizing it, we are looking at a series of stars that the Egyptians called the decans that followed series about 10 degrees apart in the sky, which is the reason why we subdivide the night and then the day also in 12 hours. And so, whenever we glanced at our watch, we are glancing deep into the past and deep into the stary origin of our timekeeping that has always been with us.

A replica of the earliest surviving telescope attributed to Galileo Galilei, on display at the Griffith Observatory. (Photo: Jim and Rhoda Morris, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

DOERING: So we have to talk about Galileo Galilei, a very important astronomer. How did Galileo's observation of the stars through his telescope shape astronomy?

TROTTA: Galileo in 1610 did something absolutely extraordinary. The significance of which slightly escapes us today because we're so used to it now. But when he heard that something that we now call a telescope, had been invented in the Netherlands, it immediately set his genius in motion to try to build his own. And in fact, after 24 hours, he had built his own telescope with no instructions, no blueprint, nothing grinding the lens himself, and so on. And when he had this telescope fashioned for himself, he did a revolutionary thing. He took it, and he pointed it to the sky. And it's a simple act of almost incredible daring, the fact that he wanted to see what matters were hidden in the sky, by the means of a device that could now give him a more powerful acuity and vision. And when he did that, all sorts of incredible sights opened up to his understanding and his ability to draw them actually. And he saw the moons of Jupiter, he discovered the fact that there were other moons revolving around another planet. He saw the phases of Venus, the fact that Venus changes its shape, just like the moon does, which is incontrovertible evidence for the fact that Venus actually orbits the Sun and not the earth. He studied the sun's sunspots, which had been already discovered, but he was the first to characterize them. He looked at the moon and he realized it's got craters and valleys and crevices and it's not that perfect object that Aristotle had said. And so the sky and the earth were made of the same substance and that was shattering in terms of changing our view of what the cosmos was made of. It's all of this together, really, any of these discoveries, and all of them together completely changed our view, not only of the universe around us, but also of our place in the universe, and our relationship with it.

DOERING: What a revolution. So Roberto, your book takes us all the way from ancient history through our relationship with the stars today. And I was fascinated, and frankly, quite alarmed to read in your book that our view of the stars is threatened today, not only by light pollution, of course, which I think a lot of us experience anyone who lives near a city, but also by artificial satellites. What's the impact of having thousands of satellites orbiting Earth?

TROTTA: Through my view, this is a dramatic ecological crisis that's unfolding silently and above our heads, without people really realizing it, and without much fuss about it. But it's as concerning there's other ecological crisis that unfortunately, we're witnessing in our time. And it's brought about by the fact that in the last few years, private companies, private space companies have launched thousands of internet satellites in low earth orbit that's 250 kilometers up, so they're relatively nearby. And space is fast becoming congested. So there is now about 10,000 satellites in near orbit. And according to some estimates that by 2030, there's going to be 100,000 satellites. And those satellites are mostly used for the purpose of providing internet service, fast internet service everywhere, at all times. But the downside, well there's many downsides, but a very concerning one is that being so low, they actually reflected the sun's light, especially at dusk through the solar panels, and also depending on the location and the season, throughout the night. And they show up as little moving dots across the firmament, which means that if you look up on a dark night, if you're lucky enough to leave under dark skies, which is increasingly difficult, of course because of light pollution, which means that you will see plenty of these little dot carving little lines across the sky. And by some estimates, unfortunately, I'm sad to report that by 2030, it's possible that we will see more artificial satellites in the sky than real stars, at which point, we will have lost the sky for good. We will never no where on earth have the opportunity to actually experience the sky, like our ancestors always had done and so will last forever, that connection with the beauty and inspiration of the eternal sublime, as Emerson put it. And that's happening, you know, launch after launch, it's happening fast and if it's not regulated or stopped soon, it will be too late to get it back.

Thousands of years ago in ancient Babylonia, astronomers divided the zodiac into equal-sized areas, each one corresponding to a constellation coalescing the analysis of the zodiac and constellations. The constellation of Orion is illustrated above. (Illustration: Johannes Hevelius, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

DOERING: And that's nothing like going to a dark sky sanctuary can resolve. I mean, if they're up there, you're gonna see them.

TROTTA: Exactly. And that's dramatic, right? Because it's already difficult enough to find the dark sky sanctuary these days. But those satellites will be everywhere, they're running around all the globe, and so you won't be able to escape them. There is no mountain that's tall enough, there is no ocean that's offshore far enough for you to escape them because they're everywhere all the time. So that's a real loss, a tragic loss of perhaps what I think of as the last global common and actually the only truly global common that humanity has shared you know across cultures, across times. Since time immemorial, the sky has been you know, everybody's but space no longer is.

DOERING: It does seem like we'd have an impoverished experience of the sky at night. And what's the impact to science, if any?

TROTTA: Yes, there was a cultural impact which I just described but also there is a scientific impact because as the satellites pass in front of astronomers telescopes, both on Earth and in space, the live trains on the pictures that astronomers take of the deep sky. And that means that up to 50%, up to half of the data of the greatest sonic observatories are rendered unusable for research. So this has got a real cost in terms of essentially nullifying half of the billion dollar efforts that astronomers are putting into studying the sky, and making important programs more difficult. For example, asteroid tracking becomes more difficult because of these tracks left by the satellites and that's really important program. For example, in order to raise alarm in case asteroids are deflected, of course, or will be threatening to life on earth. All the satellites render this so much harder and it's a real scientific problem.

The overview effect is a mental transportation to “a state of awe” expressed by some astronauts while viewing the Earth from space. The image above was taken by Apollo 8 crewmember Bill Anders on December 24, 1968, at mission time 075:49:07 (16:40 UTC), while in orbit around the Moon, showing the Earth rising for the third time above the lunar horizon. (Photo: Bill Anders, Wikimedia Common, Public Domain)

DOERING: How do you think studying the stars and looking up the sky can inspire us to take better care of our planet?

TROTTA: I think it does and I think it does, because it affords us the opportunity for ones to see ourselves from a different cosmic perspective. Let me just backtrack for a second and talk for a minute about what is called the "Overview Effect", which is this mystical, if you want to call it that experience that many astronauts report when they get to see our fragile, beautiful blue and white planet from space. Right when they behold, this little globe floating in the darkness of space in the velvet of the universe and they realize that we're so fragile, we're so little, and all the squabbles, all the wars, all the terrible things that are happening to our planet really should not be happening because we need to see ourselves as being global citizens of one spaceship, spaceship earth. Which is our own only protection against the hostility of space. So that's the overview effect that many astronauts have reported feeling something move inside their heart or inside their soul, when they perceive Earth from that. And that's not available to everybody, of course, but we earthbound beings if we look up, we won't see ourselves from up there but we can still see what's out there and transport ourselves into this cosmic perspective and understand, in looking at the void between the glowing stars and looking at the majesty of the night sky, and realizing the smallness and the fragility of our life compared to that. I think that's a very important and very needed antidote to the hubris, the technologically driven hubris that's wreaking havoc to our planet. You know, think about loss of biodiversity, climate change, the terrible wars that we're witnessing every day, all of this needs to be put in a different perspective, in perspective of the stars. And if we start measuring our actions and the impact of our actions on the cosmic perspective, I think that the politics and the economics and the kinds of societies that we want to build on a planet will change radically. It could inspire us to build a better world.

DOERING: It is really special, this perspective that we're given by being able to look up at the stars send up instruments and people up there to look back at Earth.

TROTTA: Absolutely, and it's something that's been only afforded to us by the technology that was actually born out of the science that was ultimately given to us by the contemplation of the stars. So in a way, our understanding of the stars is something that we owe the stars themselves.

Roberto Trotta is a cosmologist at the International School for Advanced Studies (SISSA) in Trieste, Italy, where he is a Professor of Theoretical Physics and the head of the newly established group in Theoretical and Scientific Data Science. He’s also a Visiting Professor of Astrostatistics at Imperial College London and author of “STARBORN: How the Stars Made Us—and Who We Would Be Without Them”. (Photo: Courtesy of Roberto Trotta)

DOERING: So Roberto, the stars have been hugely important for humans for how our societies have developed. How important have they been in your life?

TROTTA: Well I realized that stars really shaped my life profoundly. And perhaps that's not so surprising for somebody who is a cosmologists by profession, and therefore very professional wouldn't even exist if it wasn't for the stars. But perhaps I hadn't realized fully how the stars had really changed the course of my personal history as much as my professional history. And that's also how I chose to actually open the book. And when I tell a story that I think prior to actually writing it in the book, I probably never told anybody. [LAUGH] And it's a story of how many, many years ago on a dark night in my native Switzerland, which is a landlocked country, which at that time, still enjoyed some quite dark skies, I had a date and my date and I were out for an evening at the theater and we were walking back home. And then we both happened to look up at the sky at a very special moment where something really special and quite magical happened. It was a meteor passing by a shooting star, if you like.

DOERING: Wow.

TROTTA: Which appeared to be the perfect, romantic moment that sparked well, something that was in the air but hadn't quite catalyzed yet. And many years later, when I actually came to reflect about my personal trajectory and history, I found myself looking into my wife's eyes and I saw the very same falling star reflected in there still, because that date that night later on 25 years plus later, that girl had become my wife. And I don't know whether that would have been quite the same story if that shooting star had not happen to fall precisely that night at that moment, in that circumstance that really, somehow brought some magic to the entire, to the entire thing and definitely changed the course of my life.

DOERING: Roberto Trotta is a cosmologist and astrophysicist and author of the book Starborn: How the Stars Made Us (and Who We Would be Without Them). Thank you for joining us.

TROTTA: Such a pleasure. Thank you for having me.

Related links:

- Learn more about professor of Astrophysics and Data Science Roberto Trotta

- Purchase Starborn: How the Stars Made Us (And Who We Would be Without Them) from Bookshop.org to support both Living on Earth and local independent bookstores

[MUSIC: The Piano Guys, “Over The Rainbow / Simple Gifts” on The Piano Guys, TPG Productions LLC]

O’NEILL: Next week on Living on Earth, marveling at the mysterious lives of plants.

SCHLANGER: One of my favorite trips was to the southern rainforests of Chile, these temperate rainforests, kind of chilly, wet places. And there is a vine that grows in this rainforest called boquila trifoliolata. And this vine has, of course, always been there, at least for human memory. But it was just recently discovered to be quite literally a chameleon vine. It can spontaneously change the shape of its leaves, the color of its leaves, the vein pattern, the texture, to match the shape, to mimic the shape of anything it's growing beside. This plant can mimic up to four different species at the same time, with different parts of its vine structure. And no one knows how this is possible. So I spent several days with the team of Ernesto Gianoli, a researcher who's studying this plant, and the vine has provoked this controversy over whether or not plants could possibly see. There are a camp of botanists who say, well, it's mimicking, spontaneously mimicking other plants--that must be a form of visual acuity, that they're taking visual information and processing it and producing this perfect mimic. But of course, plants don't have brains. So where would they be transposing that visual information into an image in the way we think of it? But plants do have a ton of photoreceptors on their leaves, more than we have in our eyes, more different types of photoreceptors. So there's some weight behind that argument. And then, the botanist himself who I was spending time with thought it was something far more sci-fi, that this plant was actually just receptive to the microbiomes of other plants, that the shape of plants is not determined by the plant itself, but rather by sort of third-party organisms.

O’NEILL: Tune in to Living on Earth next time to hear Zoe Schlanger talk about her new book The Light Eaters: How the Unseen World of Plant Intelligence Offers a New Understanding of Life on Earth.

[MUSIC: The Piano Guys, “Over The Rainbow / Simple Gifts” on The Piano Guys, TPG Productions LLC]

O’NEILL: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Shanzay Asif, Paloma Beltran, Josh Croom, Karen Elterman, Swayam Gagneja, Sommer Heyman, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Nana Mohammed, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Allison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and YouTube Music, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments at loe dot org. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Jenni Doering

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth