July 12, 2024

Air Date: July 12, 2024

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Hawaiian Kids Win Climate Case

View the page for this story

Thirteen young plaintiffs who took the Hawaii Department of Transportation to court over its role in the climate crisis have won a settlement that requires the agency to fast-track public transit, new bike lanes, and electric vehicles. Attorney Joanna Zeigler represented the plaintiffs for Our Children’s Trust and joins Host Aynsley O’Neill to discuss the new and cleaner future of transportation in Hawaii. (09:20)

New Tech Finds More Cancer Risk

View the page for this story

New technology reveals startling levels of cancer-causing ethylene oxide gas wafting from industrial sources in Cancer Alley, Louisiana. Peter DeCarlo of Johns Hopkins University led the research and joins Host Jenni Doering to explain the findings and the health risks for residents. (10:33)

Environmental Justice Denial

View the page for this story

Black residents of Cancer Alley who live next door to polluting industrial plants say they are the victims of environmental discrimination. But their attempts to seek justice through a key provision of the Civil Rights Act are being met with racist pushback. Monique Harden of the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice joins Host Jenni Doering to discuss the ongoing attacks against environmental justice. (12:39)

Note on Emerging Science: Why Do Some Lizards and Snakes Have Horns?

View the page for this story

Snakes and lizards have independently evolved horns or spikes on their heads at least 69 times, and recent research finds evidence that horns may provide camouflage for predators that ambush their prey rather than actively chasing it. Living on Earth’s Don Lyman has this note on emerging science. (01:50)

From the History Books

View the page for this story

This week, Living on Earth Contributor Peter Dykstra joins Host Aynsley O’Neill to celebrate the July 12, 1817, birth of nature writer Henry David Thoreau. They also mark the July 1850 invention of icemaking using compressed air. (03:01)

Climate Action to Protect the Oceans

View the page for this story

Island nations are facing a flooded future and running out of time for the world to get its climate act together. So, they turned to the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, and in May 2024, a court found that countries do have legal obligations to stop greenhouse gases from polluting the world’s oceans. Katie Surma is a reporter with Inside Climate News and joins Host Jenni Doering to explain what the decision could mean for global climate action. (08:33)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

240712 Transcript

HOSTS: Jenni Doering, Aynsley O’Neill

GUESTS: Peter DeCarlo, Monique Harden, Katie Surma, Joanna Zeigler

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Don Lyman

[THEME]

DOERING: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

DOERING: I’m Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

Young plaintiffs concerned about the climate crisis put Hawaii on a path to cleaner transportation.

ZEIGLER: I think this case is a blueprint for transformative change for the rest of the country and the world. It shows that government can come to the table, it can listen to the youth, it doesn’t have to fight, and a resolution is possible.

DOERING: Also, new technology reveals startling levels of ethylene oxide gas in “Cancer Alley.”

DECARLO: When you clean up a very toxic site, the kind of maximum allowable risk is one in 10,000, cancer risk. And we were above that, for pretty much the entirety of our study area. At the fence line, occasionally, we would see levels that got even 1000 times higher than that.

DOERING: Those stories and more, this week on Living on Earth—stick around!’

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Hawaiian Kids Win Climate Case

Hawai‘i’s youth plaintiffs celebrate the historic settlement reached with the Hawai‘i Department of Transportation. (Photo: Robin Loznak, Our Children's Trust)

DOERING: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Jenni Doering

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

In 2023, massive wildfires on Maui in Hawaii destroyed the town of Lahaina and killed around 100 people. Teenager Charlotte Madin was safe on Oahu but says the fires were a frightening example of what can happen in a world of climate disruption.

MADIN: I was shocked, honestly, because I was present for the wildfires on Big Island a few years previously, which were really scary and terrifying. And they didn't even come that close to where I was, it was just the ash from the sky, the weird cloud coloration. And I was just thinking, it must be so awful to have to go through all that. And then we have a plaintiff who, whose family actually did have to go through that. And I just, I want to do everything I can to stop it to prevent it and just to slow it down a little bit by doing whatever I can in the state of Hawaii or beyond.

O’NEILL: So with the goal of slowing down the climate crisis, in June 2022 Charlotte and twelve fellow youth plaintiffs went to court. They filed a first-of-its-kind lawsuit against the Hawaii Department of Transportation on the basis that its highway expansion plans violated their constitutional right to “a clean and healthful environment.” You pretty much need a car to get around the islands and a plane ride to hop between them. And without a major course correction from Hawaii DOT, the transportation sector is on track to make up 60% of the state’s total greenhouse gas emissions by 2030. Just before the case went to trial, Hawaii DOT and the youth plaintiffs reached a landmark settlement agreement that puts the state on a new course to zero carbon transportation. Joanna Zeigler is a Staff Attorney with Our Children’s Trust, which represented the youth plaintiffs, and she joins me now to discuss. Joanna, welcome to Living on Earth!

ZEIGLER: Thank you. Thanks for having me.

O'NEILL: Joanna, why is this settlement agreement considered sort of, first of its kind? What's so new or revolutionary about it?

ZEIGLER: Yeah, so the settlement agreement is really a win for the youth plaintiffs and for the state of Hawaii really generally, and future generations. And it is requiring transformative change within the Department of Transportation, and is the first of its kind in a climate change action where the government actually was willing to come to the table to sit down with the youth plaintiffs and create an agreement that was really a recognition of the need for climate justice.

The settlement court order requires the Hawai‘i Department of Transportation to reach zero emissions by 2045. (Photo: Sun Brokie, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

O'NEILL: And what sort of changes to the transportation system are they planning to make?

ZEIGLER: Yes, so the settlement agreement really is a recognition on the part of the Department of Transportation that a paradigm shift is needed. So business as usual within the department is going to have to be changed. The business as usual model of expansion of highway lane miles is no longer an option. So the electrification of the transportation sector is very important. And in fact, the Department of Transportation has already committed to $40 million to infrastructure for charging electric vehicles within the first five years of entering into the agreement. And in addition to electrification, the Department of Transportation has committed to completing the pedestrian and bike network within the state. Right now, the options for riding a bike and being a pedestrian are somewhat dangerous. There's not a lot of sidewalks, there's not a lot of safe bike lanes. And so the department has committed to creating a safer biking network and pedestrian network, which is really important. And then the settlement agreement also recognizes the need for expansion of transit. The Department of Transportation has a lot of control over funding for transit. And so that will also need to be a priority in this new paradigm shift within the transportation sector.

Hawai‘i is already facing the effects of climate change. A flash drought linked to climate change is cited as a major factor in the deadly August 2023 wildfire in Maui. The wildfire killed approximately 100 people and is pictured here from the International Space Station. (Photo: NASA Johnson, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

O'NEILL: And what exactly is the Hawaii Department of Transportation required to do according to this agreement?

ZEIGLER: The agreement contains some really transformative provisions, and the most important provision is that the Department of Transportation is required to create a greenhouse gas reduction plan. And it will do that within a year of the settlement agreement. And what's really significant about the plan is that it requires the Department of Transportation to create a pathway to zero emissions by 2045. And in addition to that, it requires five year benchmarks to be established, so where the department needs to be in 2030, 2035, 2040, in order to get to those zero emissions of 2045. And importantly, the youth and the community are provided an opportunity to give feedback into that greenhouse gas reduction plan. They'll get notice 30 days before the finalization of the plan, and provided an opportunity to provide that feedback to be able to consult with their experts, and to hopefully incorporate that feedback into the plan. One other significant element of the settlement agreement is that it creates a youth council. So not only will the youth be provided an opportunity to give feedback to the greenhouse gas reduction plan, and then also receive annual updates from the Department of Transportation, but it will also be provided an opportunity to participate in a youth council. And that will be a gathering of the youth plaintiffs who are interested and youth from the community. And they'll be able to give support and input to the Department of Transportation and its policies with regard to climate change and other actions. And then I'll just mention one other really significant part of the settlement is that the court will retain jurisdiction over it for the next 21 years. So if there is a need to go back to court, we have that opportunity.

O'NEILL: Now, to what extent will air transportation be included here? From what I understand, there are inter-island flights that are common in Hawaii. And I mean those certainly will emit greenhouse gases.

ZEIGLER: Yes, so the settlement agreement covers ground, marine, and inter-island air transportation. And so it will require the Department of Transportation to begin promoting alternative ways to travel inter-island and as the technology progresses, there are certainly means for electrification of inter-island travel because it is such a short distance. And so that will definitely be a part of this transformation under the settlement agreement.

Inter-island flights in Hawai‘i contribute to the state’s emissions. Without significant changes, the transportation sector is projected to make up 60% of the state’s emissions by 2030. The settlement order seeks to change that. (Photo: James Brennan, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

O'NEILL: And Joanna, what kind of reaction have you seen from Hawaii's Department of Transportation? How are they reacting to this case and the settlement?

ZEIGLER: The Director of the Department of Transportation, Ed Sniffen, was really an integral part of coming to this agreement. He really came to the table, he was very supportive of the youth plaintiffs, and he was willing to discuss what was needed in order to create to this paradigm shift within the department. And so I would say the reaction is positive. We have really great support from Director Sniffin. And in fact, as part of the settlement agreement, the Department of Transportation has created a Climate Change Mitigation and Culture Manager. And that person will be at the head of a unit that is designated to enforce the settlement and look at climate mitigation within the Department of Transportation. So overall, just a very positive interaction and experience from the department.

O'NEILL: And I want to expand out a little bit, I mean, we're looking at sort of this case study in Hawaii. But what do you see as the broader implications of this case, this settlement, for, you know, the rest of the country or even the rest of the world?

Staff Attorney Joanna Zeigler (left) says she hopes this case can serve as a model for other state governments willing to collaborate with youth advocates. (Photo: Robin Loznak, Our Children's Trust)

ZEIGLER: I think this case is a blueprint for transformative change for the rest of the country and the world, I think, for two reasons. One, it shows that government can come to the table, it can listen to the youth, it doesn't have to fight, and a resolution is possible and positive change can come of discussing and talking and creating a settlement like this. And then for the second reason, I think Hawaii is going to be a model for other departments of transportation and transportation systems as it creates this greenhouse gas reduction plan, as it begins to transform the transportation sector, and really works towards zero emissions within transportation. I think other states can look to Hawaii and use it as a model in their own state.

Joanna Zeigler is a Staff Attorney with our Children’s Trust, and she is working on several of Our Children’s cases, including Navahine vs. Hawai‘i Department of Transportation. (Photo: Robin Loznak, Our Children's Trust)

O'NEILL: Joanna, what do you want listeners to take away from a case like this?

ZEIGLER: I would just encourage folks to keep watching Hawaii and to watch as the implementation of the settlement agreement progresses. As we say, the work is starting now. We've resolved the lawsuit, but we have a lot of work ahead of us. And so I think as we move forward, it's just important for folks to keep watching and learning and seeing how Hawaii progresses as we move forward.

O'NEILL: Joanna Zeigler is a Staff Attorney with Our Children's Trust. Joanna, thank you so much for taking the time with me today.

ZEIGLER: Thank you.

Related links:

- Our Children’s Trust

- Learn more about Navahine vs. Hawai‘i Department of Transportation

- Read the settlement agreement here

[MUSIC: Keola Beamer, “Kalena Kai” on Wooden Boat, by Keola Beamer, Dancing Cat Records]

O’NEILL: Coming up, legal attacks on environmental justice efforts could imperil communities in Cancer Alley and beyond. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Zander Jazz Trio. “Let There Be Love” on Misty, Zander Jazz Trio]

New Tech Finds More Cancer Risk

Johns Hopkins University researchers studied ethylene oxide across Louisiana's petrochemical corridor. Companies often resort to venting or flaring (pictured above) where gas is burned as a safety measure. Venting and flaring of petrochemical plants are seen as a significant source of gas waste and toxic chemical emissions. (Photo: Peter DeCarlo)

O’NEILL: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

The eighty-five-mile stretch of the Mississippi River between Baton Rouge and New Orleans is known as “Cancer Alley” because communities there experience the highest risk of cancer from industrial air pollution in the United States. And a major source of that risk comes from facilities that emit ethylene oxide, a colorless, sweet-smelling gas used in sterilizing medical equipment. Exposure to that chemical is linked to lymphoma, leukemia, and breast cancer. In March the US Environmental Protection Agency finalized rules that will soon require industry to install pollution controls that would reduce ethylene oxide emissions by about 90 percent. Still, new research suggests even those reductions may fall short of what’s needed. Environmental engineers from Johns Hopkins University found that ethylene oxide was present in Cancer Alley at levels far higher than what is considered safe. Joining me now is senior author of the paper Peter DeCarlo, associate professor at Johns Hopkins. Welcome to Living on Earth Peter!

DECARLO: Thank you for having me.

DOERING: So what kinds of numbers are we talking about? Can you paint us a picture here?

DECARLO: Eleven parts per trillion is the level of ethylene oxide associated with a one in 10,000 chance of getting cancer over a lifetime of exposure. Just to put that in context, 11 parts per trillion is 11 molecules of ethylene oxide per trillion molecules of air, which is really small. When we think about ozone pollution in the summertime, we're in parts per billion, which is a thousand times higher than that. And when we think about climate change, and CO2, we're a million times higher than that. So we're talking about really, really small concentrations of ethylene oxide, and the levels that we saw exceeded that 11 parts per trillion value, which indicates higher than one in 10,000 chance of getting cancer over a lifetime of exposure.

The mobile laboratory or “lab on wheels” that Johns Hopkins researchers used to measure ethylene oxide across a section of Louisiana. (Photo: Peter DeCarlo)

DOERING: So what kinds of levels were you seeing in the research that you conducted?

DECARLO: The concentrations at the census tract level, got up to over 50 parts per trillion, which is over five times that kind of safe, I wouldn't even call it safe, it's the limit of what's allowed at a cleaned up Superfund site. So when you clean up a very toxic site, the kind of maximum allowable risk is one in 10,000, cancer risk. And we were above that, for pretty much the entirety of our study area. At the fence line, occasionally, we would see levels that got even 1000 times higher than that. And that these are direct emissions from these facilities, they're plumes that are kind of coming across fence lines in the air. And we're seeing concentrations in the 10 to 40 parts per billion range, which again, is 1000 times higher than that parts per trillion level that we're talking about. And we certainly were able to identify plumes of ethylene oxide up to 10 kilometers or more away from these facilities. So this stuff travels with the air.

DOERING: So what are the dangers associated with long term exposure of this chemical?

DECARLO: So ethylene oxide is a carcinogen. It's an mutagen, which means it affects our DNA. So the molecule will impact our DNA and increase the likelihood that we get cancer. And I just want to point out that it's that same method of action is why it's a really good chemical sterilizer. So it's used for sterilizing medical equipment, and to kill all the bacteria and viruses that may be on that.

DOERING: So how exactly is this chemical getting out into the surrounding air?

DECARLO: So some of that is probably coming out through leaks in pipes or tubing that was moving the gas from one place to another on these facilities, we did see an association, often with increased levels of carbon dioxide. When you see carbon dioxide in the air, it usually means there's some kind of combustion, so it could be associated with a combustion event or occurrence. So if they're trying to flare or burn up ethylene oxide, as it gets vented, or exhausted, that would lead to higher concentrations of both ethylene oxide and carbon dioxide. So it's not clear we weren't on the sites themselves, making measurements on each piece of equipment we weren't allowed to be. And so what we were able to do was drive around these facilities and around the fence line, and try to get an idea of of what was coming out and seeing associated other chemicals with that helps give clues on what processes maybe emitting the ethylene oxide.

DOERING: So from what I understand the sampling that you used for the study is pretty different from what's previously been used to track ethylene oxide. What was different about your research methods?

Medical devices that require ethylene oxide (EtO) sterilization include heart valves, pacemakers, surgical kits, gowns, drapes, ventilators, syringes, and catheters (shown above). (Photo: Thirteen of Clubs, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

DECARLO: So in 2018, EPA changed the risk values for ethylene oxide, and they reduce them pretty substantially. And along with that, there came a recognition that the current methods of measuring ethylene oxide were not sufficient to get to the levels needed this 11 part per trillion level, we need to understand kind of risk at the community level or the background level. The other really important thing to note is that the current measurement technology that has been used for a while by EPA has been shown to have what's known as artifacts. And what they were doing in the sampling technique is you take a stainless steel canister and you pull air into it, you take that back to the lab and you make a measurement. There have been now acknowledged problems with that methodology, leading to uncertainty in the concentrations of ethylene oxide measured. And so it seems to be that storage in the container led to some reactions that increase the concentration of ethylene oxide or did something to make it so that the ethylene oxide wasn't accurate. And so along with that ruling came the need for new technology to measure ethylene oxide quickly and at these concentrations. And two of the instruments that we had along with us in Louisiana, were born from that need for new technology. So the other really cool thing about what we were doing down there is we took these brand new instrument technologies and we put them in a mobile lab. And so a mobile lab is essentially lab on wheels, there's a generator on the back of the mobile lab or a large battery pack to power instrumentation as we drive around. And this really sensitive brand new instrumentation is making measurements at about one measurement per second, which allows us to get really detailed spatial resolution. And just to give you some perspective on that, when you're driving about 30 miles an hour, one second data is about a 10 meter resolution. So we're getting about 10 meter resolution as we drive along with this new technology making measurements of ethylene oxide.

DOERING: So to what extent do you think that the different methodology could be accounting for the fact that you were able to find levels much higher than EPA thought the concentrations of ethylene oxide were in this area?

DECARLO: So I think the reason that our measurements exceeded the model values from EPA is that well, first of all, there are no measurements in that area to compare directly to. And so the modeling data was all we had to go on, those models rely on what's called the emission inventory. And the emission inventory is an annual emission report that's compiled usually at the state or local level, and then sent to EPA and aggregated into a national emissions inventory. So the state of Louisiana compiles the data from Louisiana, sends it to EPA, it goes into the emissions inventory. And then that forms the basis of the expected ethylene oxide emissions from facilities in Louisiana. Now, where this becomes a problem, is there's no accounting, there's no way to check that. And so the measurements that we did, were essentially a check of that. We look at the ambient levels, the air tox screening assessment gives us what they think the ambient level should be based on those emissions. And we saw this mismatch and a factor of five to 10, higher, in some cases, 20 times higher for the census track level concentrations of ethylene oxide.

Peter DeCarlo is an associate professor of environmental health and engineering at Johns Hopkins University. (Photo: Courtesy of Peter DeCarlo)

DOERING: Sounds like your research was filling a really huge gap here. I mean, if you know, we're relying on estimates for cancer risk, Estimates of how much ethylene oxide really potent carcinogen, is actually in the air in these communities. What does that mean for the risks that they're being exposed to?

DECARLO: That's a great question. I mean, I think the whole motivation for this project was to find a place where we identified the kind of highest density of ethylene oxide producing facilities, and go see what was there. Because we didn't have a lot of measurements, this technology did not exist up until a few years ago. And so we didn't have the ability to do this type of measurement. But also to be clear, the infrastructure nationally for measuring hazardous air pollutants is not as strong as the infrastructure measuring things like particulate matter, or NOx, or carbon monoxide. And so the hazardous air pollutants are a different category, they're much more difficult to measure and there's a lot fewer sites across the US measuring these hazardous air pollutants. So what we found in Louisiana isn't necessarily unique to Louisiana. It's unique in the sense that it's the highest concentration of these ethylene oxide producing plants. But the fact that we have to compare measured values to model values, because that's all we have to compare to is not unique. It's something that's pretty widespread across the US.

DOERING: Peter, I know you're a scientist but if you can reflect a little bit, what can communities do in cancer alley with this information?

DECARLO: Ideally, we want communities to be able to use this type of information to advocate for themselves. I'm not a resident of this area and so I think the conversation about what can be done really belongs with the people who live there, and the agencies that are tasked to protect them. But I think, you know, one potential option that is available is now that we have these numbers and these estimated cancer risks based on these numbers it's part of the conversation about- should you build any more facilities in an area that already is exceeding what's considered safe from a cleaned up Superfund site, right? If the cancer risk is higher than 1 in 10,000, then that's not good enough for a cleanedup superfund site that shouldn't be good enough for what's going on now. And there certainly shouldn't be any additional burden added to that area. And so I think community groups now have something that they can point to and say "we have a pretty high burden right now of environmental pollution, we don't need any more, and don't give us any more". And I think that's something that's valid that can come from this type of data.

DOERING: Peter DeCarlo is an Associate Professor of Environmental Health and engineering at Johns Hopkins University. Thanks so much for joining us.

DECARLO: Thank you for having me. It's been a pleasure.

Related links:

- Read the study led by Johns Hopkins University on Ethylene Oxide Levels in Louisiana

- The Guardian | “Air in Louisiana’s ‘Cancer Alley’ Likely More Toxic Than Previously Thought”

- Inside Climate News | “For Louisiana’s ‘Cancer Alley,’ Study Shows an Even Graver Risk from Toxic Gasses”

- Learn more about the EPA’s emissions inventory

- Learn more about Johns Hopkins associate professor of environmental health and engineering Peter DeCarlo, the senior author in this study

[MUSIC: Cal Scott and Kevin Burke, “The Lighthouse Keeper’s Waltz” on Across the Black River, by Cal Scott and Kevin Burke, Loftus Music – out of phase - MONO mix made]

Environmental Justice Denial

Cancer risk associated with emissions of chloroprene from the above Denka plant in Reserve, Louisiana was a key concern of the environmental justice groups who filed the 2022 civil rights complaint with EPA. (Photo: Lee Hedgepeth/Inside Climate News)

DOERING: Ethylene oxide is just one of many industrial chemicals poisoning Black communities in Cancer Alley. But their attempts to seek justice are being met with pushback. In 2022 local environmental justice groups sought help from the Environmental Protection Agency under part of the Civil Rights Act known as Title VI. They said that by approving so many industrial facilities in majority Black districts, the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality had engaged in racial discrimination. The EPA opened a civil rights investigation and hopes were high that justice would come. But then state Attorney General Jeff Landry, who is now Louisiana’s Governor, sued EPA, alleging that its bid to address longstanding environmental racism was itself a form of “reverse discrimination.” Because of that lawsuit the Department of Justice got involved, and EPA dropped its civil rights investigation in Cancer Alley, shattering the hopes of environmental justice advocates. The attacks on Title VI of the Civil Rights Act have since spread beyond Cancer Alley. And in April, Republican Attorneys General in nearly two dozen states argued EPA should no longer consider race alongside pollution risks. Monique Harden of the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice is here to discuss. Monique, welcome back to Living on Earth!

HARDEN: Thanks for having me back.

DOERING: So what is Title VI? And what does it have to do with environmental health?

HARDEN: Well, Title VI is the Civil Rights Act of the United States. It's a federal law. This is a law that was a tremendous achievement by the Civil Rights Movement, through the decades following Jim Crow, that really ushered us into a new place where we get closer to democracy and equal protection under the law in the United States. What Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 sets forth is a prohibition in the use of federal dollars by any entity that would result in the discrimination of people on the basis of race, color, national origin.

DOERING: And how has Title VI of the Civil Rights Act been used in relation to environmental justice?

HARDEN: It's been used to enforce environmental justice. What we know as, to be a fact is that many of our state environmental agencies are mostly funded with federal dollars. So that obliges each of those state agencies that are, you know, responsible for permitting pollution, monitoring it, enforcing regulations to ensure that all of their actions and activities are not discriminatory. And what we know to be a fact is that discrimination is happening across the country, where you have this, extreme disparities in communities that are disproportionately burdened with toxic pollution, and that disproportionate is based on race. So that Black people, communities are more likely than white communities to have a toxic facility operating or spewing pollution where we live. And so the state agencies, while they're looking at environmental laws, or should be, they also have an obligation, as anyone else who receives federal dollars, to look at civil rights laws and protections. And some states have been really hostile in attacking those civil rights protections, one of those states being where I live, in Louisiana.

DOERING: Right, so Monique, could you walk me through these recent challenges to the Civil Rights Act and Title VI and where they stand?

ExxonMobil’s Baton Rouge Refinery along Louisiana’s “Cancer Alley.” (Photo: Jim Bowen, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

HARDEN: Well, it goes, a little bit of history: the earliest Title VI civil rights complaint that was filed by communities seeking environmental justice was in 1989. Since then, there's been this large backlog of civil rights complaints that have been filed with the US Environmental Protection Agency. This is a federal agency that has the obligation to ensure that dollars that flow through that agency to states or localities are not used in a way that discriminates on the basis of race. And so those complaints were not being reviewed, investigated, brought to resolution by the EPA, which was and continues to be a major issue and concern for environmental justice advocates like myself and the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice. However, recently, the Environmental Protection Agency under the Biden-Harris administration accepted two civil rights complaints that were filed in St. John Parish and St. James Parish. These are communities located in Louisiana's Cancer Alley. And their complaints charged discrimination on the part of our Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality and our Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals. EPA took both of those complaints up under one investigation, they began the work of resolving the decisions that have been a pattern of actions and decisions by each of those agencies, and got them to the table to make agreements for real transformative change that would remedy the situation. This was a document that was a near-final settlement agreement between the communities and the state agencies. One of the terms of this agreement would have required the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality to withhold permitting for any polluting facility that would lead to racial discrimination.

DOERING: Wow, so there's almost a settlement agreement. What happens next?

HARDEN: [LAUGHS] Well, just before signatures were written on the document, our attorney general at the time for Louisiana, a man named Jeff Landry, brought a lawsuit in a jurist federal court that is far on the other side of the state away from where St. John Parish and St. James Parish are located. So he was able to find a judge who would agree and has, you know, a record of an ideology with decisions. And that really put the stops on the Department of Justice moving forward, by their decision. EPA was working within its administrative capacity to bring these civil rights complaints to resolution. Once the lawsuit was filed -- which just, you know, heinous arguments, ridiculous basis, but nonetheless, it was filed by the Attorney General of Louisiana -- the Department of Justice held back and didn't fight back against it to defend the work that EPA was doing, which is ultimately upholding Title VI of the Civil Rights Act, which was written for communities in St. John Parish and St. James Parish, Black communities facing discrimination by state governments funded by the federal government. And so that really set major disappointment within the environmental justice community, that the Department of Justice is not as serious as it should be about upholding our laws when it comes to ending racial discrimination.

Louisiana Governor Jeff Landry filed the reverse discrimination complaint that halted EPA’s civil rights investigation in Cancer Alley when he was the Attorney General of the state. (Photo: Louisiana State Attorney General’s Office, public domain)

DOERING: How do you respond to Jeff Landry's claim that it's actually racist for EPA to consider the race of impacted communities?

HARDEN: The way in which you respond is by enforcing what the law says, which is that there's a prohibition against racial discrimination, that forces analysis of racial impacts. This "colorblind" patina he wants to put on, to use as a cloak to cover actual structural racism, really has no sway with anyone. You, just taking a walk in Louisiana's Cancer Alley, it becomes really clear: Black residents in modest homes, in the shadows of towering industrial facilities, spewing toxic poison in their air and dumping it in their waterways. And so doing something about that is required by Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. It's not reverse discrimination to end racial discrimination. And the argument is specious, it holds no weight or water. But again, the Department of Justice really failed, I believe, in, you know, meeting this moment with a vigorous defense of civil rights of the residents in St. John and St. James Parish that they so deserve.

DOERING: You know, Monique, earlier in the broadcast, we heard about high levels of ethylene oxide in Cancer Alley, which of course, as you note is home to a lot of Black communities that already face a lot of industrial pollution. What do you think this weakening of Title VI that's ongoing means for communities like that?

HARDEN: It was the ethylene oxide regulations that EPA announced the spring of this year, that reduces the emissions considerably. It's a major step forward that regulatory action is still a place where change and progress can be made. But I would look at the ethylene oxide as one of many chemicals that can be released in Black and other communities of color by not just one but several industrial facilities that are all otherwise permitted to operate. And so while the reductions on ethylene oxide is important, and it shows a way for additional cuts that can be made in pollution by regulation, there's still this civil rights question that needs to be addressed, which is where is our Department of Justice, in preventing the violations of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act when it comes to toxic pollution and environmental hazards?

DOERING: You know, as I understand the challenges to Title VI have spread to many other states as well, with other attorney generals raising questions about Title VI. Why are they pursuing this weakening? And what do they have to gain from it?

HARDEN: Part of it is this political ideology that wants to do away with all racial equality in the country and stand up and bring reinforcements to white supremacy. That's part of it. Another part of it is working at the behest of large industrial polluters that are making massive profits where they're not required to clean up or reduce their pollution. And so those two dynamics are at play here with the Attorney Generals that are hostile to EPA meeting its obligation as a federal agency to prevent civil rights violations.

Monique Harden is the Director of Law and Policy and Community Engagement Program Manager at the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice. (Photo: Courtesy of Deep South Center for Environmental Justice)

DOERING: What can communities do in the face of these challenges to the Civil Rights Act, and to Title VI?

HARDEN: There's just more collective action and power building that's needed. Not as many people as you would think understand the important role that Title VI of the Civil Rights has. And so there's an education piece that's needed, of course, and with that education, informing collective action for robust enforcement of it. And so that's really our work ahead. We've got now a blueprint of what's possible that can change Cancer Alley in Louisiana. What is this blueprint? It was the near-final settlement agreement that EPA was able to develop with state agencies who didn't want the removal of federal dollars, because that's the ultimate remedy of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act. If an entity receiving federal dollars doesn't want to comply with the law, that entity is no longer funded with federal dollars. It impacts every aspect of our daily lives.

DOERING: Monique Harden is the Director of Law and Policy and Community Engagement Program Manager at the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice. Thank you so much, Monique.

HARDEN: Thank you, Jenni.

Related links:

- Inside Climate News | “In Louisiana’s ‘Cancer Alley,’ Excitement Over New Emissions Rules Is Tempered by a Legal Challenge to Federal Environmental Justice Efforts”

- Read the draft settlement agreement between the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality and US EPA

- Read the Louisiana Attorney General’s complaint against EPA

- Learn about environmental justice and Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

- About Monique Harden

[MUSIC: James Booker, “Medley, Pretty Baby-Wining Boy Blues” live at the Montreux Jazz Festival 1978, by James Booker, on Youtube]

O’NEILL: Just ahead, a breakthrough for intergovernmental climate action. That’s coming up on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Keola Beamer, “E Ku’u Morning Dew” on Moe’uhane Kika - Tales From the Dream Guitar, by Keola Beamer, Dancing Cat Records]

Note on Emerging Science: Why Do Some Lizards and Snakes Have Horns?

Species like the Saharan horned viper may have horns to aid in camouflage. (Photo: Richard Castell, Castell Ecology, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

O’NEILL: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Aynsley O’Neill

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

In a moment, we’ll turn a page in the history books with Peter Dykstra, but first this note on emerging science from Don Lyman.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

LYMAN: Some snakes and lizards have horns or spikes on their heads – but why?

In the past, studies have hypothesized that these horns might be for courtship, defense, or camouflage. A team led by herpetologist Federico Banfi from the University of Antwerp wondered if the presence or absence of horns might come down to hunting style.

The scientists determined that most horned snakes and lizards remain still and ambush their prey, rather than actively pursuing it. They hypothesized that horns and spikes might provide camouflage to sit and wait predators, but could make more active snakes and lizards easier for predators and prey to spot.

The researchers looked for evolutionary clues. If the horns didn’t provide a camouflage benefit in active hunters, they might not evolve as often as in sit and wait predators.

With the help of an evolutionary tree, the team found that lizards and snakes independently evolved horns on the top of their heads, eyebrows, or snouts at least 69 times.

A greater short horned lizard sunbathes on a rock. (Photo: Carla Kishinami, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

That said, horns or spikes on these reptiles aren’t the norm and only adorn less than 10% of the species the scientists analyzed. But among those horned lizards and snakes, the vast majority, or 94%, were the “sit and wait” kind of predator as opposed to those that actively move around while hunting.

It’s still possible that horns also serve some other benefit, like looking cool to a potential mate. We haven’t been able to reach any lizards to ask.

That’s this week’s note on emerging science. I’m Don Lyman.

Related links:

- Read the full study on the evolutionary development of horns in lizards and snakes

- FunMorph: Animal Morphology Research Group

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

From the History Books

The northern shore of Walden Pond, close to where Thoreau conducted his famous experiment in minimal living. (Photo: Terryballard, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

O'NEILL: And now it's time to turn to our living on Earth contributor Peter Dykstra. He's got a few stories from the history books that we're going to take a look at now. Hey, Peter, what do you have for me this week?

DYKSTRA: Hi. Aynsley. The first one comes on July 12th 1817, which was the birthdate of Henry David Thoreau. That's the way it apparently was pronounced back in the 19th century, even though we say Thoreau these days. He was born, of course in Concord, Massachusetts, not “Con-cord”. His books, including Walden and Cape Cod, are regarded as some of the 19th century's best writing on our relationship with nature. I was really touched by Cape Cod, which is a journal of Thoreau's walk from Chatham up to Provincetown, the entire area known as the Outer Cape, in what was then of pristine beach, but even then he saw signs of human incursion and development and wrote about them. That's one of the things that has made me fascinated with Cape Cod for my entire life.

Henry David Thoreau wore many hats: nature enthusiast, writer, poet, and philosopher. He played a key role in the transcendentalist movement. His most famous work, Walden, explores the idea of a simple life immersed in nature. (Photo: National Portrait Gallery, Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

O'NEILL: Well, first of all, Peter, thank you for that Thoreau correction before we even got started. His writing has really been so influential in the modern environmentalist movement.

DYKSTRA: The books are absolutely timeless, and they tell of lessons learned about dealing with the environment. And of course, lessons not learned.

O'NEILL: Hmmm. And still to be learned. All right, Peter, what else do you have for me this week?

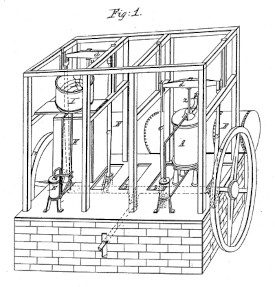

DYKSTRA: July 14th 1850. There's a doctor in Apalachicola, Florida, named John Gorrie. He was seeking a method of cooling off patients that were suffering from malaria and yellow fever. Gorrie demonstrated his invention for manufacturing ice using highly compressed air. Air compression is still the basis so many years later in refrigeration, air conditioning, and ice making.

O'NEILL: Gorrie's method of compressed air is a really interesting insight into how people make ice. I don't know anything about it. If I need ice, I just pour some water into an ice cube tray and put it in the freezer.

DYKSTRA: That's the easy way to do it here in the 21st century. But Gorrie is credited and is a local hero, at least in the Florida Panhandle for saving untold lives. And it's the reason that places like Phoenix and Las Vegas, and even Los Angeles became large cities because all of a sudden they became livable.

Illustration of John Gorrie's ice-making apparatus. This illustration is taken from the U.S. patent document 8080, dated May 6, 1851. (Photo: Author Unknown, Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

O'NEILL: Alright. Well, Peter, thank you so much for bringing us these stories from the history books. Peter Dykstra is a living on Earth contributor and we will talk to you again soon.

DYKSTRA: All right Aynsley, thanks a lot and talk to you soon.

O'NEILL: And there's more on the stories on our website. That's L-O-E dot O-R-G.

Related links:

- Henry David Thoreau’s biography at the Walden Woods Project

- Learn more about Gorrie’s invention

[MUSIC: Caribbean Jazz Project, “Todo Aquel Ayer” on The Caribbean Jazz Project, Heads Up International]

Climate Action to Protect the Oceans

The International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea published an advisory opinion stating that carbon emissions are polluting the oceans and that governments therefore have a legal obligation to reduce those emissions. (Photo: International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea photo)

DOERING: The 2015 Paris Agreement was celebrated as a turning point for nations coming together to tackle the climate crisis. But nearly a decade later, the world is way off track from the goal of limiting global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius. The Paris Agreement is not a legally binding document, so it can’t compel nations to rapidly reduce carbon emissions. So island nations facing a flooded future and running out of time turned for help to a different United Nations mechanism, the Convention on the Law of the Sea. And in May, the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea issued an advisory opinion stating that countries do have legal obligations to stop greenhouse gases from polluting the world’s oceans. For more on what this means, we are joined now by Katie Surma, a reporter with our media partner Inside Climate News. Katie, welcome back to Living on Earth!

SURMA: Thanks for having me.

DOERING: So this announcement requires governments to take "all necessary measures" to protect the oceans from greenhouse gas emissions. What does that actually mean?

SURMA: So the tribunal laid out, it was over, I think 150 pages going into detail about specific steps that nations that are bound by the treaty have to take to comply with this ruling. And so they have to do things like enact laws and regulations that meet the goals of the Paris Agreement, that 1.5 warming threshold. They need to provide technical assistance to other countries. So, more developed countries need to transfer technology and provide financial assistance to less developed countries. And like I said, the decision is 150 pages.

DOERING: Wow, that sounds pretty extensive.

SURMA: Yeah, it really is. The tribunal started its opinion in addressing this question of science as well, which was pretty remarkable. Attorneys who I talked to, who practice international environmental law, really emphasized the importance of that. The tribunal went into what the best available science said, making reference to things like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, remarking that the science on greenhouse gases and what they do to the oceans, it's not a debate anymore. And so just that affirmative statement from a court about what the science says, and then stitching it together with what the law says it's a first-of-its-kind decision. And one, I think, that lawyers will be digesting for some time to understand what the implications are.

DOERING: Now, we do have the Paris agreement. And even before that, the Kyoto Protocol, what's new or different about this particular opinion?

Members of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea. Their advisory opinion was sought by a group of small island states who were frustrated at slow progress on climate change. (Photo: International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea photo)

SURMA: Yeah, and you are hitting on a major implication of this advisory opinion. The Paris Agreement is part of what's known as the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. And they are largely political negotiations. And the sort of high point of that, in a lot of people's eyes has been the Paris Agreement, which under that agreement, countries are legally obligated to periodically report their goals to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. And that is their only legal obligation. They don't need to meet the goals that they set, they just have to set them. And just some additional context here, you know, if you add up all of the goals that countries have submitted so far, that puts the world on a warming pathway to 2.8 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. And that amount of warming, this is not hyperbole, it's catastrophic. I mean, this will affect millions of people's lives around the world. Severe drought, sea level rise, more severe storms, flooding, etc. And so one of the big issues here that the International Tribunal on the Law of the Sea was looking at was this question of is the Paris Agreement enough? Is this climate framework convention, is that the only game in town here when it comes to what countries are legally obligated to do? And it gave a definitive answer of no, the Paris Agreement is not it. There are these other laws out there that countries have agreed to, and they apply in the context of climate change.

Tremendous legal victory by COSIS today @ITLOS_TIDM ⚖️

— COSIS on Climate Change and International Law (@cosis_ccil) May 21, 2024

COSIS official press release ???? pic.twitter.com/4rJTgRIMlb

DOERING: So Katie, this is the first advisory opinion that creates legal obligations for countries related to climate change. Why did this happen now and why focus on the oceans?

SURMA: So a small group of small island countries came together at the Glasgow COP in Scotland a few years ago. They banded together because they were frustrated with the lack of ambition, the slow pace of these political negotiations. That group is known as the Commission of Small Island States or COSIS. The founding members were Antigua and Barbuda, as well as Tuvalu, and some of the other countries were Vanuatu, St. Kitts and St. Lucia. And until now, the oceans have largely been sidelined from climate discourse and wrongly so because oceans are the world's biggest carbon sink. They have absorbed, I think it's something like over 90% of Earth's heating since pre industrial times, over 25% or around 25% of greenhouse gases and those things affect the ocean, it's killing off marine life through acidification and heating. And there's only so much heating the ocean can take or absorb. And scientists say that we're at a tipping point here. Once you know, a certain level of heating or greenhouse gas absorption is breached, it can catalyze a number of effects that we have no understanding of what that will do. Beyond that, there's sea level rise. So that's broadly the context of how this all came together. These countries have been known as the conscience of the COP process for a long time and feel that they haven't been taken seriously. And they also feel that the financial loss and damages has not been forthcoming. So this decision's really a powerful tool in the hands of those countries that lack sort of the political power. Now they have the legal backup to their positions.

Katie Surma is a reporter with Inside Climate News. (Photo: Courtesy of Katie Surma)

DOERING: To what extent does this opinion give small island states any power to sue countries that are stalling climate action?

SURMA: Yeah, there's a number of legal consequences that will flow from this advisory opinion or that are expected to flow. I asked a number of attorneys who represent these states, are you planning to sue big emitters in state-state litigation, no one wants to say whether that's in the works or not, because in the international realm of things, diplomacy is so important. But technically, I mean, a country like the Bahamas could, you know, take a country like the United States to court before the International Court of Justice, over failure to meet its legal obligations. Again, from what I hear, that's not likely to happen. But this advisory opinion also provides legal precedent for litigants at the national level, to rely on it. So NGOs or citizens could use this advisory opinion as a basis for suing their own governments or other governments. It's also very likely that in Azerbaijan later this year at the COP negotiations that we're going to be hearing this advisory opinion referenced. So that realm between the diplomatic, the political and the legal, that's one of the most fascinating things to watch how this all plays out.

DOERING: Katie Surma is a reporter for our media partner Inside Climate News. Thank you so much, Katie.

SURMA: Thanks, Jenni.

Related links:

- Inside Climate News | “‘Historic’ Advisory Opinion on Climate Change Says Countries Must Prevent Greenhouse Gases from Harming Oceans”

- Katie Surma’s Profile at ICN

[MUSIC: Caribbean Jazz Project, “Three Amigos” on The Caribbean Jazz Project, Heads Up International]

O’NEILL: Next week on Living on Earth, What’s at stake for environmental justice and climate change if Donald Trump gets a second term? We’ll take a deep dive into his administration’s regulatory rollbacks and the fallout from pulling the US out of the Paris Climate Agreement.

SITTENFELD: To have Trump so abruptly walk away from this international agreement, as it was really starting to take hold. And as we were really starting to transition to a clean energy economy around the world once and for all was just horrifying and sent exactly the wrong message about where our country was going and the role that we were going to play.

O’NEILL: And we’ll hear about where the country might be headed on these issues if there’s a red wave this November. Be sure to tune in to Living on Earth next week to hear our coverage of the Republican National Convention and the party platform on climate and environment.

[MUSIC: Caribbean Jazz Project, “Three Amigos” on The Caribbean Jazz Project, Heads Up International]

O’NEILL: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Shanzay Asif, Paloma Beltran, Kayla Bradley, Josh Croom, Karen Elterman, Swayam Gagneja, Sommer Heyman, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Nana Mohammed, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Allison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and YouTube Music, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at @livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments at loe.org. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth