July 19, 2024

Air Date: July 19, 2024

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

The Transformation of J. D. Vance

/ Dan GearinoView the page for this story

J. D.VANCE : Donald Trump’s running mate, Ohio Senator J. D. Vance, once held moderate Republican stances on climate and clean energy. But he now echoes Trump on the “Green New Scam” and unleashing domestic fossil fuels. Ohio-based Inside Climate News Reporter Dan Gearino joins Hosts Steve Curwood and Jenni Doering to contrast the J. D. Vance of a few years ago with that of today. (08:21)

Climate Voter Power

View the page for this story

Climate may not always top the list of voter concerns, but research suggests it can tip the scales in US presidential elections, including the 2020 election which came down to 44,000 votes. So the Environmental Voter Project is trying to mobilize nearly 5 million registered voters who rate environment or climate as a top concern but might not otherwise turn out this November. Nathaniel Stinnett is its founder and director and joined Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill to explain why this latent voting bloc is worth tapping into. (08:21)

GOP Rep. Bentz on Climate

View the page for this story

Republican Cliff Bentz represents Oregon’s second district in Congress, where he chairs the House Natural Resources Subcommittee on Water, Oceans and Wildlife and is part of the Conservative Climate Caucus. He sat down with Host Steve Curwood to share his views on conservative approaches to climate adaptation, carbon capture and storage, wildfire prevention, public lands stewardship and more. (26:03)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

240719 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood and Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Representative Cliff Bentz

REPORTERS: Dan Gearino

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

GOP Vice Presidential nominee J. D. Vance praises Trump on the climate.

VANCE: A leader who rejects Joe Biden and Kamala Harris’ ‘Green New Scam’, and fights to bring back our great American factories, we need President Donald J. Trump. [CHEERS]

CURWOOD: Also, climate-concerned voters could tip the scales.

STINNETT: We've identified 4.8 million already-registered environment-first voters, who are unlikely to vote this fall. Only 44,000 voters decided the last presidential election. If climate voters show up, they could absolutely decide the 2024 election.

Plus, Republican Congressman Cliff Bentz on conservative climate action, on Living on Earth—stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

The Transformation of J. D. Vance

Former President Trump picked Ohio Senator JD Vance to be his running mate in November’s presidential election. (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

The 2024 US presidential election has already been tumultuous but, Steve, in some respects it’s just beginning.

[RNC HALL SFX]

And at the Republican National Convention in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, the party coalesced around presidential nominee Donald Trump, his chosen running mate J. D. Vance and the GOP platform.

Representative Michael Waltz from Florida, who Co-Chaired the party platform committee spoke on the first night.

WALTZ: We will unleash American energy and flood the world with clean, cheap American oil and gas -- Drill Baby Drill! [CHEERS]

And, Jenni, in his nomination acceptance speech, J. D. Vance put the focus squarely on American energy and manufacturing jobs.

[CROWD CHANTS, "J.D.! J.D.! J.D.!"]

VANCE: But, my fellow Americans, here in this stage and watching at home, this moment is not about me. It’s about all of us, and it’s about who we’re fighting for. It’s about the auto worker in Michigan wondering why out-of-touch politicians are destroying their jobs. It’s about the factory worker in Wisconsin who makes things with their hands and is proud of American craftsmanship. It’s about the energy worker in Pennsylvania and Ohio who doesn’t understand why Joe Biden is willing to buy energy from tin-pot dictators from across the world, when he can buy it from his own citizens right here in our own country.

And of course, the Senator from Ohio always brought it back to the former President.

VANCE: A leader who rejects Joe Biden and Kamala Harris’ ‘Green New Scam’, and fights to bring back our great American factories, we need President Donald J. Trump. [CHEERS]

DOERING: Steve as you know with just two years in the US senate J. D. Vance doesn’t have much of a record in politics.

But neither did Donald Trump when he came down the escalator of Trump Tower in 2015 to announce his candidacy.

CURWOOD: Right, so joining us now to help unpack what we do know about J. D. Vance when it comes to climate and environment is Dan Gearino, an Inside Climate News reporter based in Columbus, Ohio.

Hey Dan, welcome back to Living on Earth!

GEARINO: Great to be here.

CURWOOD: So, Dan, how would you describe the J. D. Vance we've seen in recent days?

GEARINO: The J. D. Vance we've seen in recent days is this version of him that came into life with his Senate campaign, which is just not that long ago, and is a lot different from the J.D. Vance we saw just a couple years before that, when he was this author of a best selling memoir, who was had a lot more of a kind of moderate republican image. One of the most interesting things about J. D. Vance is the extent of the transformation of kind of the way he talks about issues and even kind of specific stances on some issues related to energy and the environment.

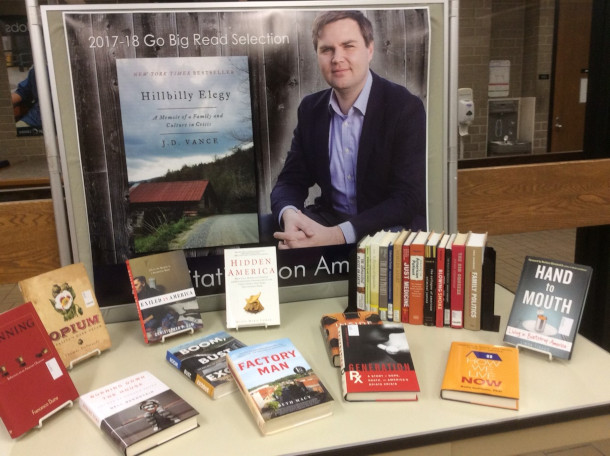

Vance made a name for himself in 2016 as author of the memoir, Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis. (Photo: college.library, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: Now, in his speech, Vance highlighted his roots in Middletown, Ohio. What's Middletown like?

GEARINO: Middletown has a steel plant that's been around for a long time and has long been the kind of core of the local economy, but it used to have a lot more industry. Middletown was probably a really nice place to live circa 1950, maybe a little bit later than that. And like so many cities of its size, it lost a lot of industry over, you know, the 1980s, 1990s. And it had a lot of poverty. It is a town that has struggled a lot and so much of what is a through line in J. D. Vance’s memoir, and a lot of what seems to have helped to form his worldview is some of the factors that led to Middletown kind of falling from its position of economic prosperity to one of real economic desperation.

CURWOOD: You know, Dan, it may be apocryphal, but supposedly CBS Radio picked Middletown, Ohio as the, quote, "American Voice" as they started to broadcast around the country. And of course, the book he wrote is called Hillbilly Elegy. So how much of a hillbilly was he there in Middletown? I guess, being raised by his grandmother, Mamaw. How does that background help Mr. Trump? Oh, and by the way, unlike probably your typical hillbilly he married the daughter of Indian immigrants.

GEARINO: This question you ask gets kind of to the core of his identity. And this is one of the most controversial aspects of how people look at and will at times criticize J. D. Vance. So first of all, Middletown is not in Appalachia. J. D. Vance comes from his family history is definitely in Appalachia, family in Kentucky, but he grew up in a part of the industrial Midwest that I don't think there's any map of Appalachia that would include Middletown. And the idea of the term hillbilly is one that is fraught for sure. There are a lot of people who are from Appalachia, who look at the way he talks about Appalachia, from his background, not being from Appalachia, and they really didn't like it. And this is something you would see across the political spectrum, but particularly Democrats and people kind of the middle of the road politically. They would basically say this is kind of a caricature of our region that is being kind of spoon fed to people who are not from the region and don't necessarily recognize it. So yeah, it's you could spend all day kind of dissecting his identity, his kind of family history and identity, it clearly forms a lot of how he views the world. He talks about Appalachia and talks about this place that he's from.

CURWOOD: And he certainly doesn't sound like Eastern Kentucky.

GEARINO: No.

Vance grew up in Middletown, Ohio, in the industrial midwest. (Photo: Sherm Cohen, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

DOERING: Now, as you mentioned, Dan, there's been a lot of talk about how J. D. Vance has gone through quite a transformation on Trump over the years. I mean, he once called Trump America's Hitler described him as really dangerous but now he's of course a fierce supporter and defender of the former president, what changed?

GEARINO: It will be interesting. I mean, in long hindsight, at some point in the future, to be able to figure out the precise point that J. D. Vance seemed to just turn on a dime in terms of the way he talks about things and his whole kind of aura as a public figure, but from our vantage point right now, I think it's pretty clear that that Senate race, the Senate race, he ultimately won because he had Trump's endorsement. It was a very crowded race. He was not leading in the polling, by adopting a Trump like tone and by very skillfully getting Trump's endorsement in a field in which there were a bunch of other candidates that wanted Trump's endorsement, desperately wanted it, he got it. And what he did was took this kind of persona that he had before as this public intellectual, this guy who wrote about Appalachia with his kind of the distance of almost an academic. A real smart guy, a guy who came from finance, a guy who went to Yale Law School, who had a part time faculty position at Ohio State briefly after he moved back to Ohio. That person was out the door. You didn't hear from him anymore. You heard this kind of very aggressive way of talking about immigrants. This real lack of nuance when so much of what defined him before was a whole bunch of nuance. I mean, one of the reasons that Hillbilly Elegy was widely read and widely liked, I would say across the political spectrum in a lot of ways, I mean, there were certainly detractors, but it was something that got a lot of respect from a lot of quarters, was that he did seem to possess some nuance when talking about what ails the industrial Midwest and talking about the solutions, and it was not this straight up partisan view. That changed dramatically, and it was around the time that he was a Senate candidate or about to become Senate candidate you also can look at when he got the beard. You look at the videos of the kind of public intellectual phase of J. D. Vance's life after returning to Ohio, you know, when you see him without the beard, you're probably gonna get the kind of the nuanced, the caveats, just a really a different guy. A lot of times if you're just watching video, and when you see the beard, you know, you're gonna get the kind of the post Trump J. D. Vance. And it's just striking.

Senator Vance has criticized former President Trump a number of times in the past but has voted in alignment for most of his Senate career. (Photo: Official White House Photo by Shealah Craighead, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: Yeah, and so let's play a clip of J. D. Vance. Speaking back in 2020 at Ohio State University. There was an event on the American dream before he aligned himself so closely with Trump,

VANCE: We of course, have a climate problem in our, in our society, one largely caused now by unrestrained emissions in China. Part of the reason we have that problem is because we're not generating energy much cleaner than we used to 30 or 40 years ago. And in fact, the biggest improvement in emissions is solar energy, which can provide a substantial amount of our power but can't provide anything like 50% of our power, definitely not 100% of our power, and through sort of, you know, our increasing reliance on natural gas, which, of course, is an improvement over dirtier forms of power, but isn't exactly the sort of thing that's going to take us to a clean energy future.

CURWOOD: What's your takeaway from the way he was talking about energy and climate back then it certainly wasn't drill, baby drill.

GEARINO: No and it wasn't especially partisan. I would say that the way he was talking about these issues back then, are like somebody who has just a basic understanding of the facts about climate change, and about the global energy economy. I mean, you could almost say that like a high schooler or even a middle schooler who has basic understanding, you know, this is a lot of common sense stuff. And what's striking is how, in hindsight, it was notable that he was making statements that are verifiable facts. It's like, oh, my goodness, what a contrast, when in fact, what he was saying it was very much a mainstream view. It was even within the Republican Party, you could be an elected Republican and say exactly what he said, and you wouldn't necessarily get into trouble. It's a different person than the one we've got now or at least a fundamentally different way of talking about these things. The guy we hear in that clip is someone who would barely recognize the guy that we heard speak at the Republican Convention.

DOERING: So Dan, as we heard, at the top of this segment, Vance mentioned, quote "the auto worker in Michigan wondering why out of touch politicians are destroying their jobs". Now that sounded like it must be a reference to the electric vehicle manufacturing incentives in the inflation Reduction Act, but the Biden administration has been creating jobs through electric vehicle incentives. So why is Vance adopting this rhetoric?

Investments in electric cars, Vance argues, will threaten auto workers’ livelihoods. (Photo: cifraser1, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

GEARINO: There is this sense in parts of the Republican Party, that this is something that will catch on with voters or has caught on with voters. It's also very much in line with what fossil fuel industries would like to see, they want to see this demonization of electric vehicles. And it's almost completely contrary to the facts of what's actually happening. The shift to electric vehicles is something that would lead to a net gain in jobs in auto jobs. And in union jobs definitely in Ohio. I mean, you can look at billions of dollars of investment in Ohio, you can look at investment in Michigan. What does shift to EV does is it creates a lot of anxiety for auto workers, because these jobs are changing, it creates kind of fertile ground if you want to kind of sow discord and make workers skeptical about this shift toward cleaner transportation. But it's just striking how contrary that is to the idea of making the US competitive in the auto economy that we're gonna have 10 years from now, 20 years from now, 30 years from now. It's almost like a strategy that has an expiration date of the November election. And maybe that's all that's needed. But um, it's one of those things when you think back to what kind of the public intellectual J. D. Vance of a couple years ago, he never would believe that he you know, it's like he would debate himself right here and say "come on, you know, let's be real here". So yeah, that is something that I also found striking when I heard that.

CURWOOD: Well thank you so much, Dan, for taking this time with us today and sharing your insights. J. D. Vance, from your own state there in Ohio. Dan Gearino is an Inside Climate News reporter based in Columbus, Ohio. We'll talk to you again soon sometime in the future, I suspect.

GEARINO: All right. Thank you very much.

Related links:

- JD Vance, US Senator for Ohio

- Watch JD Vance’s Speech at the Republican National Convention

[MUSIC: “The President’s Own” U.S. Marine Band, “The Stars and Stripes Forever” by John Philip Sousa, Recorded in the John Philip Sousa Band Hall at Marine Barracks Annex in Washington, D.C.]

DOERING: Coming up after the break, how climate concerns can change the outcome of U.S. presidential elections. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Keith Jarrett, Jan Garbarek, Palle Danielsson, Jon Christensen, “Country” on My Song, ECM Records GmbH]

Climate Voter Power

A study from the University of Colorado Boulder analyzed voting trends and used predictive modeling to conclude that climate-focused voter turnout played a pivotal role in electing Joe Biden in 2020. (Photo: Phil Roeder, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

Climate may not always top the list of voter concerns, but compelling research suggests it can tip the scales in US presidential elections.

And researchers say that environment focused voters were an essential part of the winning margin for Joe Biden’s 2020 bid for the White House.

Their surveys also found that a quarter of Republicans who see climate change as “very important” went for Biden in that election.

And their numbers show that if levels of concern about the climate had remained stagnant from polling in 2016, Donald Trump would have likely won re-election in 2020.

CURWOOD: And Jenni, the numbers of climate focused voters today may still be small compared to other constituencies, but when elections are very close every vote does make a difference.

And of course the climate emergency is only getting worse.

And that is why the Environmental Voter Project is trying to mobilize nearly 5 million environment-first voters they have identified through polling who might not otherwise turn out.

So, Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill spoke with founder and executive director Nathaniel Stinnett.

Let’s take a listen.

STINNETT: Remember, the 2020 presidential election was so close that it was decided by just 44,000 people in three states: Wisconsin, Arizona, and Georgia. 44,000 voters decided the 2020 presidential election. And so there are a whole bunch of issue constituency groups who could have had an impact. But for climate voters in particular, a recent University of Colorado Boulder study of polls and voter files and predictive models, not just in those three states, but also in other important battleground states showed that the increase in climate concerned voters from 2016 to 2020, so new climate voters in that 2020 election, had a large enough impact that it delivered the White House to Joe Biden. So climate voters didn't just have an impact in 2020, there's good reason to believe that they literally decided the election, at least for the White House.

O'NEILL: Well, so let's paint a picture of an environment first voter, how does the EVP define that?

STINNETT: We define it as people who are already registered to vote, and they either list climate change as their number one priority, Or they list clean air, clean water, and the environment as their number one priority. So these are people who don't just care about environmental issues, it is their top priority.

O'NEILL: When many people picture somebody who cares about the environment, they might be thinking, young, liberal person, large metal water bottle and driving a Prius. How accurate is that representation of an environment-first voter?

STINNETT: So it's not inaccurate, but there's a lot more nuance than people might otherwise think. So yes, environment-first voters are disproportionately young, and they are disproportionately progressive. But what some people might not know is that the second largest age group of environment-first voters, is people aged 65 and up. So we need to start thinking of the climate movement, and the environmental movement as not just being young hipsters, but also being grandmothers and grandfathers because it's increasingly, a movement made up of 20 year olds and 60 year olds and 70 year olds.

O'NEILL: Now, Nathaniel, when politicians in Washington, DC talk about environment, they don't always lump together clean air, clean water, and climate action. So why does the Environmental Voter Project do that when they define an environment-first voter?

This year’s presidential election could be decided by environment-first voters in swing states. (Photo: Original photos by Gage Skidmore. Adapted and republished by Emma Kaden. Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

STINNETT: Well, for two reasons. One is just logistically speaking, we need to try to isolate a group of people who we can define and then mobilize to vote. And it's always easier to do that, if you're not parsing it down by particular sub-issues, or particular policy proposals. But the second reason is, we at the Environmental Voter Project care about all of those sub-issues. We care about the climate crisis, we care about cleaning up toxic air and toxic water. We care about the environment. And we firmly believe that if we dramatically increase the number of voters who care about those issues, then politicians will respond. And yes, each policy proposal presents a different set of issues. And oftentimes politicians will think one way or the other. But the one thing we're confident of is nothing motivates a politician more than the prospect of winning or losing an election. So no matter what environmental policy they are presented with, if there are more and more environmental voters in their district, each year, these politicians will be more likely to lead on clean air, to lead on clean water, and to lead on the climate crisis, because we've created this voter demand for it in their district.

O'NEILL: And when you take a look at both climate, but then also clean air, clean water, do you have any numbers on how those different proportions play out?

STINNETT: So the reason we try to catch both of those sort of subgroups of environmentalists, is because we often expect there to not be perfect overlap. We expect there to be big differences or at least measurable differences between people who care deeply about the climate crisis, as opposed to people who care deeply about other environmental issues. But there isn't that much of a difference. Every time we measure this, we find that people who care about one environmental issue tend to also care deeply about other environmental issues. And the numbers have been pretty steadily going up. We have found that across the United States, roughly 8% or 9% of registered voters are likely to list climate or other environmental issues as their top priority, and that aligns with most public polling that we're seeing.

O'NEILL: But Nathaniel, I've seen the statistic that according to the Pew Research Center, protecting the environment doesn't even make the top 10 priorities of American voters in 2024. So why do environment-first voters matter?

STINNETT: Well, first off, let's just say it's true that there are far, far too few climate-first and environment-first voters. And that lack of political power is much of the reason why politicians rarely lead on climate. Because when there are too few voters who prioritize climate, politicians don't feel the need to address it. But to get to your question, the reason it's important still, is because there are millions of non-voters who do care deeply about climate and environment. And they could make a huge difference if they show up on election day. But that if is a really, really big, underlined, bold IF, because climate first and environment first voters don't always show up.

Stinnett argues that, regardless of a candidate’s political party, they care about getting votes. By mobilizing environment-first voters, he hopes to make the environment less of a partisan issue. (Photo: Courtesy of Nathaniel Stinnett)

O'NEILL: In that case, to what extent do you think they might determine the outcome of this upcoming election?

STINNETT: So at the Environmental Voter Project, we work in 19 states, and we've identified 4.8 million already-registered environment-first voters who are unlikely to vote this fall, unless they get mobilized to do so. But that's a huge number, especially when you consider that only 44,000 voters decided the last presidential election. So the climate movement has a lot of potential electoral power pent up here. It's just a question of whether it will be actualized. Now as far as could they make a difference? Oh, my gosh, absolutely. I mean, let's just look at two of the most important swing states. In Pennsylvania, a state that was decided by 80,000 votes in 2020. The Environmental Voter Project has identified 250,000 of these low-propensity environment-first voters. Another example in Nevada, another crucial swing state that was decided by just 33,000 votes four years ago, we've identified 110,000 of these low-propensity climate voters So in short, if climate voters show up, they can absolutely decide the 2024 election.

O'NEILL: Nathaniel Stinnett, founder and executive director of the Environmental Voter Project, speaking with Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill.

Related links:

- Learn more about the Environmental Voter Project

- Research indicates that climate-first voters may have decided the 2020 presidential election.

- Follow our partner, Inside Climate News,’ coverage of the 2024 election season.

[MUSIC: Hap Palmer, Woody Guthrie, “This Land Is Your Land” on Patriotic and Morning Time Songs, by Woody “Guthrie, Smithsonian Folkways Recordings]

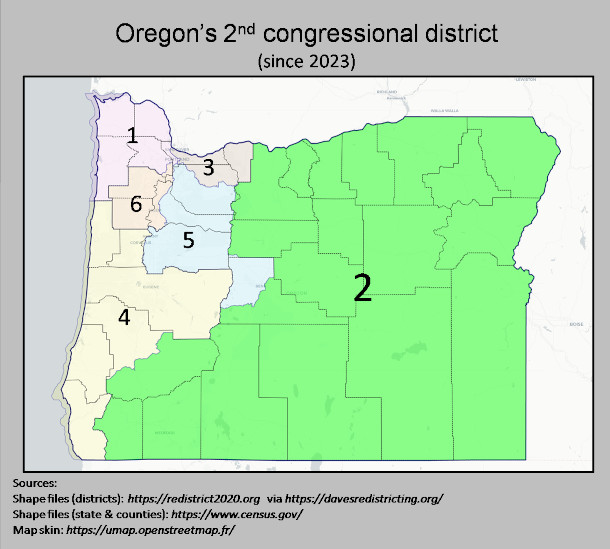

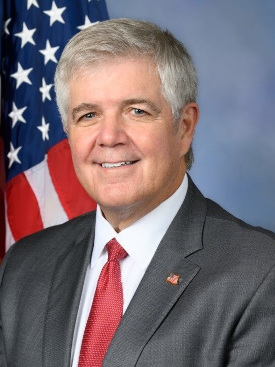

GOP Rep. Bentz on Climate

Representative Cliff Bentz (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: We turn now to an in-depth conversation about how conservative values can shape climate and environment policy with Republican Congressman Cliff Bentz of Oregon.

He chairs the House Natural Resources Subcommittee on Water, Oceans, and Wildlife and is part of the Conservative Climate Caucus.

Congressman Bentz has represented the second district in Oregon since 2020 and he’s running for a third term.

And Jenni, you know a lot about this part of the country.

DOERING: Yes, Steve, Crater Lake National Park is a real public lands jewel, it’s one of my favorite parks.

In total the district Congressman Bentz represents covers around two-thirds of the state, or 45 million acres.

Several native tribes have lived in the area for thousands of years, including the Klamath or Modoc, Northern Paiute, and Nez Perce peoples, to name a few.

The Columbia, Klamath, and Snake Rivers have been vital sources of food for them and are important to hydro and transporting cargo to this day.

CURWOOD: Well, Oregon has faced intense climate troubles in recent years, including a series of wildfires over Labor Day in 2020 that burned more than a million acres and destroyed an estimated five thousand homes and businesses in the state.

Then in 2021 a deadly heat dome hit the state and temperatures soared to 119 degrees Fahrenheit.

So, here’s republican representative Cliff Bentz on the line now from Washington to discuss these challenges.

Welcome to Living on Earth, Congressman!

BENTZ: Steve, thank you so much for inviting me. I've listened to your show many times. I'm very happy to be on it.

CURWOOD: Well, it's our pleasure to have you. So Congressman, you're a member of the Conservative Climate Caucus. What does that caucus bring to the Republican Party during this time of the Republican Convention and presidential nomination and such?

BENTZ: I think it points out that folks are aware of the fact that it's getting hotter and that the climate continues to evolve, and that we're aware of it as a party, and that issues that involve the climate are important to us. And that we have an organization of folks that are aware of the value of adaptation. Also, we really want folks to understand that we get it, there is a climate and it deserves our attention.

Above highlighted in green is the area that covers Oregon’s second congressional district which Congressman Cliff Bentz has represented since 2021. (Photo: CX Zoom, Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: So what would you say is the appropriate Republican agenda now on climate?

BENTZ: Well, that the awareness is, of course, critically important. But in my work for 12 years in the Oregon legislature, I had an occasion to serve as Co-chair of the Carbon Committee. And the challenge there was trying to bring some semblance of balance to the discussions involving energy and water and agriculture and all the other things that we rely upon, in light of what I saw as the mistaken belief that we can immediately turn around our climate. And we can't. Much of what has happened is baked in. That was a phrase that was actually used by scientists working with Oregon State University. And we have to figure out how we're going to manage through 30 to 40 years of what we're now seeing across the United States. And that managing through requires careful thought and an understanding of our limitations. And so I think that the Republican approach to issues of climate has to be one of awareness of the challenges of mitigation when you're looking at a worldwide issue, as opposed to just what goes on in the United States, and also of adaptation and innovation and all the things that we should be doing at both the state level than here in Congress.

CURWOOD: Well, let's talk about mitigation. You know, this is a worldwide problem. What should a Republican administration be doing about this as a worldwide problem?

BENTZ: Well, I think it should continue its effort to transition the world from coal over to natural gas. That's one of the reasons the United States has been so successful in reducing its carbon footprint, because we've moved from a coal based economy in many respects to a natural gas driven one, and we have a great deal of that resource. And it's very difficult to have a conversation about climate without talking about the impact that Russia has had on world natural gas prices, and the Biden administration's unexplainable, if you will, decision to bar or reduce natural gas exports in the light of the war. Shifting back to what we should be doing as a party, when it comes to mitigation, we should be calling out to China the fact that it's generating three to four times more CO2 than any of the rest of the countries in the world. And it ought to be doing more to try to slow that. And so that kind of disregard for people who are trying to breathe the air. And so from a worldwide level, we should be calling that out and saying, hey, you need to do something about it. China will say that, of course, they are doing something about it, and they just aren't doing enough.

China accounted for 35% of global CO2 emissions in 2023, according to the International Energy Agency. (Photo: Sheila, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Let's talk a little bit more about China. How could we influence China to reduce its emissions? We're not very friendly right now. I mean, the Biden administration has imposed a I think 100% tariff on electric cars from China, for example. Things are pretty tense. How do we come together with them?

BENTZ: What I saw as the most likely thing to drive China toward recognizing the damage it's doing to the environment, is its own people. And those folks are starting to recognize that China's approach to clean air, which is to apparently ignore the problem, is killing them, and literally killing people in their cities, because the air is so filthy. And so I think, ultimately, that the Chinese people themselves are going to say, enough, and force their government to do something about it. But I also would say that when you're in a what has recently been a third world country, China, if you go out into the countryside, you'll see that it still is in many respects, folks there are much more interested in driving their economy forward, I think. And they would say that the environment comes second to their economy. And so until they figure out that they need to take their climate into account, they're not going to. So I'm just saying, they have a problem. I think it's gonna be up to their people to try to figure out how to do it. I don't think they're listening to us. So I think they're driven by things other than what the United States might want them to do.

CURWOOD: Let's talk a little bit more about natural gas. I mean, the US Energy Administration said a couple of years ago that emissions from burning natural gas do account for about 35% of total US energy related CO2 emissions. So citing natural gas as a transition fuel is an important point. But what happens after that transition?

BENTZ: So another great question, I actually happened to meet with some folks this morning and discuss this exact issue. What I think is many times overlooked when it comes to natural gas is the high probability of our being able to continue to use it while we either store the CO2 underground, or determine ways of greening up natural gas through the inclusion of hydrogen. Or in some cases, right now we call it "moo" gas, but it's gas from agricultural activities. And we mix that with fossil fuel natural gas to drive down the CO2 content, but that's to overlook some of the new technology that is being developed to remove CO2 from natural gas, thus allowing us to continue to use that means of providing energy. So I don't think we need to just say it's a bridge fuel, I think we can say if we can reach this point of being able to store the CO2, then we can keep using natural gas. By the way, most of Oregon, if you go down about eight or nine, ten thousand feet deep into the ground, you'll find basalt and saltwater. And if you pump CO2 down into that saltwater, it will turn into rock. And it doesn't take a million years to do it. And so people should look into some of these possibilities. I know California already did a complete basalt audit of the state of Oregon in anticipation of just such the thing.

CURWOOD: Congressman, I noticed that you are a member of the Wildfire Caucus. And given that your district there in Oregon has had several fires already this year, I think the Salt Creek Fire, for example, has burned what couple, 3000 acres? I mean, how should a Trump administration go forward about dealing with increasing fires?

BENTZ: Well, thank you so much for asking, I'm actually going back to my district next week and meeting with people regarding fires that are burning right now in Central Oregon and on the edge of my district. What needs to happen, and I believe that the Trump administration will be far more sensitive to these challenges than has been the Biden administration, and that is getting back into the woods rapidly and removing the dramatic increase in understory undergrowth. We have close to 100 million acres of forest in the western United States. And believe it or not, in places we have 2000 stems per acre, these are trees, when the normal amount should be something like 80. We have to be able to go into the forests with mechanized means to remove that understory so that these massive, huge, unstoppable fires can in some fashion be slowed down. And yet, you'll see litigation after litigation after litigation to try to stop people from going in and trying to reduce this huge buildup of fuel. And by the way, if you have 1000 stems per acre, which we do, they're all slurping up what little water there is. And there isn't enough for 1000 stems per acre. And so those trees become drier and drier in these situations, as the water is taken up by too many plants trying to stay alive. And so the trick is adaptation. I keep emphasizing this, I did this back in Oregon, where I would say at our Carbon Committee, I said, look, you guys, this 30 to 40 years situation is baked in. Yes, we can move to natural gas and dramatically reduce CO2. But if we stopped all CO2 production today in this world, we still would have 30 to 40 years of hot, hot, hot. So adapting to this is extremely important. I think the Trump administration would do a much better job than is currently occurring under the Biden administration to address our issues in the forests.

CURWOOD: So let's talk about the details of adaptation. That is preparing ourselves to deal with the increasing heat. What items do you have in mind? What's your agenda along those lines? For not just the forest, but you know, a lot of people live in cities, a lot of people live in suburbs, people live everywhere in this country. And by now it seems like almost everyone is affected by this rising heat situation.

Congressman Bentz argues that if the US can reduce emissions from natural gas through carbon capture and storage, we can continue to use it as an energy source in the future. (Photo: Port of San Diego, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BENTZ: Oh, they certainly are. I would say that having grown up and been raised on a cattle ranch in far eastern Oregon in the high desert region, very close to Nevada, where every drop of water was important, and we woke up every morning wondering if we were going to get rain, and that was from the time I was a very little kid, three to four years old, recognizing the incredible value of water. And that's why I became a water attorney. And that's why I'm very happy to be Chair of the Subcommittee on Water, Wildlife, and Fisheries here in Congress. And the focus I've had on several hearings out in California has been on recharging aquifers with some of the snowmelt that comes rapidly off the mountains along the eastern side of California, the eastern edge, and the question is how can we store more of that water? Many people will say, build more reservoirs. Litigation has stopped almost all of that. So the real challenge is how do we replenish the aquifers which have been pumped dry by much of the farming operation up and down the Central Valley? They're now lifting water 3000 feet. Literally 3000 feet out of the aquifers below the Central Valley. Well the trick is how do we go to the aquifers that exist between 3000 feet in depth and the surface? With snowmelt. And we can do it. There are new techniques where you can use magnetic resonance machines to see where water will be taken up. And we can start using those to shepherd water as it comes off the mountains in the early spring back into these aquifers. And that's something that we're absolutely going to have to do for the people in California and other places up and down the West Coast, frankly, across all of the western United States. The other thing we should be doing is improving our watersheds so that we can receive more water from our mountains as we clean up and better manage our forests.

Wildfires in Eastern Oregon. (Photo: Bureau of Land Management Washington and Oregon, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: That’s Republican Congressman Cliff Bentz of Oregon. We’ll be back in a moment with more of our conversation. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay with us!

[MUSIC: Mason Daring, “Only for You” on Mason Daring, by Mason Daring, Daring Records]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: David Lewis Luong, “Twilight Dreams” on Vibes, by David Luong, Lewis Luong Music]

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. We’re back now with more of our conversation with Congressman Cliff Bentz, a Republican who represents Oregon’s second district.

CURWOOD: Well, let's talk a little bit more about water. I think the Biden administration has launched this task force to restore natural fish populations in the Columbia River Basin, as you know, of course this goes through Oregon, your neck of the woods. Now, you've expressed the importance of energy production on the Lower Snake River dams. What's the conservative approach to dealing with restoring native fish populations and preserving energy?

Removing underbrush fuel from overgrown forests could slow powerful wildfires down. (Photo: Jay LaCroix, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BENTZ: Yes, great question. I'm very appreciative of you asking it, I would, and have called out National Marine Fisheries' failure to look at what's truly causing the problem right now with fish on the Columbia. And the true cause of our loss of our incredibly valuable fish is ocean conditions. And yet, if you go to NMFS, National Marine Fisheries, you'll find that they're turning, in significant part, a blind eye to the ocean. They'll focus their attention instead on the Columbia River system. I would call out that the fish loss down to the last dam on the Columbia River system is about equal to or perhaps a little less than that which is on the Fraser River up in Canada, which has zero dams on it. About half of the fish are lost through depredation and other damage on the way from the smolt stage in the upper reaches of these rivers down to the ocean. When they go into the ocean, about 95% of the fish are lost before they come back. And so obviously, the focus should be on the ocean, they shouldn't be checking to see what the impact of sewage being dumped into the water outside of Seattle is, they should be looking at the impact of increasing temperature, they should be looking at the impact of incredibly aggressive fishing by other nations beyond the 200 mile limit, they should be looking at the cause of smolt mortality in the ocean, they should be looking at all of these things. To go back to the Snake River dams they create when they're generating the most they can generate, about 3000 megawatts. And some people would say, well, that's a modest amount. But the truth of it is, it's firm power. And that firm power is extraordinarily important when it comes to balancing intermittent power, such as that which is supplied by solar and wind of which we have a lot in Oregon, and they're getting a lot more. But that balancing function that almost like a huge battery function, hugely important. And so to listen to people talk about taking those dams out, those Lower Snake River dams, which I think is probably the precursor of other dam removal, and getting rid of that green clean power, ridiculous. And I've been very clear in so stating.

CURWOOD: So let's talk a little bit about the land. You grew up on a ranch as a as a young man, I suspect you could ride a horse fairly well then , if you had cattle you were ranching. What should the Trump administration now do with America's public lands? What are some really important changes that need to be made compared to what the Biden administration is doing?

Congressman Bentz disagrees with calls to remove the Lower Snake River Dam and other dams, pointing to the reliable, green power these dams provide to communities. (Photo: Backbone Campaign, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BENTZ: So I've been working with a local group and the county I live in, I think, many times people don't understand the sheer size of the Western United States, I know my district is 73,000 square miles in size. My county I live in is 9 million acres. There had been much discussion by some that want to make a portion of that 9 million acres into a national monument. I can't think of anything worse, to be honest with you. I hope I wouldn't do this, but there's many who think that people who are trying to make a living on that land who include many of my former clients when I was a lawyer for many of the ranchers out there, to leave and not run cattle any longer. And what people need to understand is the incredible value of having folks that live in these vast open areas that when a fire starts can go put it out. These are huge, huge areas. And one of the things that people really don't understand is what has happened when it comes to invasive species, whether it's Canadian thistle or rush skeletonweed, or spotted knapweed, or other types of these invasive species, what's happening is the integrity of what we call the natural food web is being damaged by these weeds. And the question is, if you create a monument, you can't come in and kill the weeds. You can't do it. And he also can't go in and try to stop fires, because many times mechanized activities are banned. And so the trick is when it comes to managing these lands, is understanding the importance of having people out there. And secondly, the importance of being able to use mechanized means of attacking some of these invasive species. And so there's all of us that have lived there and grown up there. And I'm, I'm a third generation Oregonian in that space. And I have to tell you, it breaks your heart to see what's happening to this land that's ignored and locked up, because you can't go in and try to, try to protect it.

CURWOOD: By the way, what role do you see for Native Americans and helping to protect these lands?

BENTZ: Well, a big one and add to that end, I've included them in the legislation I'm going to be introducing soon, as having the ability to use motorized access back into the area we're proposing, or will be proposing, for wilderness designation. And so I think the native peoples who are familiar with that space and understand what it takes to try to protect it are going to be all in when it comes to means of keeping people on the land, including them.

CURWOOD: Let's talk about the US Fish and Wildlife Service. I believe you've recently written to the service urging them to delist the gray wolf as a protected species. Why are you taking that approach?

BENTZ: So the US Fish and Wildlife actually recommended delisting and were told they couldn't by a judge. So US Fish agrees with me. We have enough wolves. And in fact, they've said, we have enough wolves to last another 100 years, right now, today. I went up to Minnesota, we held a hearing up there on exactly this issue. They have between three and four thousand wolves in Minnesota. Huge damage to their deer herds. We had people attend our hearing in Minnesota on the wolf, breaking down into tears. Actually, we went out to a farm, and the lady and her husband who owned the farm, she was explaining how she would not allow her three little kids to be out in the yard for fear of a wolf attacking them. I mean, that's how far this situation has gone. The question is, how many wolves is enough? If Minnesota has three to four thousand, should they have ten or fifteen thousand? And that's the same is true for the grizzly bear. We have thousands. The initial thought had been we needed two thousand. Now I think we have eight thousand grizzly bears. Okay, does New York City want grizzly bears? I mean, the question is, how much is enough and who gets to bear the cost? Certainly the folks in Minnesota, out in the country are bearing the cost, fear of having their kids attacked by a wolf. We went out in their field, saw where their calves had been killed by wolves, and then saw wolf tracks in a driveway literally, literally, within 200 yards of their house. Anyway, the challenge is how many is enough? I would say Oregon's doing a decent job. We have two to three hundred. And the local folks think that that's enough packs of wolves for Oregon. I'm sure there's much disagreement, but this issue is one that deserves lots of attention, lots of thought.

CURWOOD: So you're an attorney. And you've done some representation of folks along water interests. Recently, the Supreme Court made a ruling, it's called the Chevron Doctrine, which has a lot to do, frankly, with how the federal government issues and implements regulations. How do you view that decision? How does that affect the issues that you're much concerned with?

Congressman Bentz argues that creating a national monument makes it difficult for people to help manage both wildfires in their area and invasive species, like the Canadian thistle. (Photo: Matt Tillet, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BENTZ: Well, I agree with the Roberts Court in deciding that the Chevron decision had given too much power to agencies, I agree with that completely. The challenge is going to be how to unwind the years of that deference. Watching the Biden administration move to in its agency approach, reverse that which the Trump administration had done, you can see why people would lose a little bit of faith in the concept of stability in the agency space, because it's not, it's pretty amazing how someone can read the Clean Air Act so differently, or the Clean Water Act so differently, as has been the case between these two administrations. So the real question now that we have courts making these decisions, is why will the courts do any better? Because the original concept under Chevron was that the agencies had a higher level of expertise in trying to sort out what we in Congress did, than do the courts. What the Roberts Court said was, this is a decision for the court not to be delegated to the agencies. And so we're going to see a dramatic shift away from agencies to courts. But what I anticipate we're going to see is a dramatic move through litigation, and then through activities here in Congress to try to reset many of the rules that have been issued, I think, in an overreaching manner, over the past 30 years under Chevron. It's not going to be a clean process. It's going to be a litigation-filled, lawsuit after lawsuit process, and how it ultimately plays out, I cannot predict, but there is going to be a shift away from agency decision making to judicial decision making, there is no doubt of it. And I think the burden is gonna be on Congress to try to do its best to weigh in when it can and and say whether or not the agencies are getting it right.

Congressman Bentz suggests delisting the gray wolf as an endangered species due to their threat to livestock and people. Oregon’s minimum count of gray wolves was 178 in 2023. However, according to Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, the actual number is likely higher. (Photo: Eric Kilby, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: And then how to judges become experts able to assess what's brought to them in litigations? Do they go out and hire masters or something to understand the subject, which is kind of like having a mirror agency?

BENTZ: Yes, that's what they do. They hire a master. Sometimes you'll also see federal judges kind of divide up areas of expertise, so that you'll have, for example, in the field of anti-trust, you have people that have a background in that space or in commercial litigation or in many of the many myriad of areas that federal judges deal in. There is no doubt that this is going to put a huge amount of pressure on the federal bench. I anticipate we'll need more judges. To your point about how will they know any better, that's going to be up to in significant part, how they are funded, and then how much work lawyers want to do in trying to educate judges up. Yeah. And when people were asking me what I thought about Chevron, I always say, well, that decision making in that space is subject to political perversion. Now we're going to go to the judicial side, and we'll see what happens there.

CURWOOD: Before you go, Congressman, let me ask you, what are your thoughts on the Inflation Reduction Act? What impact is it having now on the farmers, ranchers, forest owners and tribes in Oregon and across the western US, for that matter, the whole country? But from your perspective, what's the impact of the Inflation Reduction Act so far?

Congressman Bentz says the Supreme Court strikedown of the Chevron Doctrine rightfully limits overreach by regulatory agencies like the Environmental Protection Agency. (Photo: Ben Schumin, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

BENTZ: What's happened, I think, is many of the things that folks thought would happen quickly are not. And that's because of the way NEPA, National Environmental Policy Act, is coming into play. The NEPA rulemaking process and environmental impact statements and environmental assessment processes takes an awful long time. And so much of what they thought that act would do hasn't yet occurred. As far as its broad impact over time, there are many things in it. Part of the Inflation Reduction Act focuses on energy, and there's a tax credit piece in the bill that is hugely problematic, and that I think it was originally thought to be around 700 billion. I've heard estimates that it's so popular that it might be as much as 3 trillion. And so there's huge stampedes of folks toward those tax credits. And I have a history of that space with Oregon's business energy tax credit. And we spent close to a billion dollars on a little bitty state before we could finally slam the door on that particular boondoggle. I fear that that's what we're going to see here. There are all kinds of businesses who recognize what a tax credit is. And if you can arrange whatever you've been doing to fit the parameters of the credit application, then you do. We call that a free ride. So you might be doing something that you would have done anyway. But suddenly, you can get a tax credit to help. And when I say help, you didn't really need it. But oh, hey, it's free money. And so that's what I see happening here under the inflation Reduction Act.

CURWOOD: We're just about out of time. So let me ask you this. What have you heard from your constituents about all of these issues? And how do you think it helps Republicans, your approach to these issues, in the upcoming elections?

Cliff Bentz is a third-generation Oregonian, raised on his family’s cattle ranches in Harney County and representative of Oregon’s second congressional district. (Photo: U.S. House of Representatives, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

BENTZ: Well, I've heard nothing but positive remarks about the reversal, the Chevron Doctrine, because the overreach by agencies in my district has been horrific for many, many years. And people are hoping that they'll get a fair shake in court that has been the case in front of what I'll say are largely nonaccountable agencies. On the issue of fire and getting back into the woods, they are ecstatic that President Trump may be reelected, because they view him as recognizing the need to get back into the woods and try to reduce the challenges that we face because of the huge, huge, huge buildup of fuel. When it comes to water and the Snake River dams and the wonderful hydro facilities that we have that have done so much for the Northwest and continue to do so with lower power rates than everybody else, they are ecstatic that Republicans may be in a position to protect the amount they pay for electricity. When it comes to energy, they are ecstatic that the hope that the Trump administration will come back in and get back to leasing lands so we don't have a huge gap seven to eight years out, when it comes to energy production. So I'll just say that there's great enthusiasm for the hope that President Trump will be reelected and then we can start heading off some of the bad things that have been happening and continue to happen.

CURWOOD: Cliff Bentz serves Oregon in the US Congress from Oregon's second congressional district, and he's looking for a third term in this fall's elections. Thanks so much, Congressman, for taking the time with us today.

BENTZ: I really appreciate it, Steve. Thank you so much.

Related links:

- Republican Congressman Cliff Bentz

- Conservative Climate Caucus

- International Energy Agency | “The Changing Landscape of Global Emissions”

- US Energy Information Administration | “Natural Gas Explained”

- Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife | “Oregon Wolf Population”

[MUSIC: Pinetop Perkins with Ann Rabson, “Careless Love” on Ladies Man, by Ledbetter, M.C. Records]

DOERING: We asked you to weigh in on what we should cover this election season, and here’s a taste of what you wrote: Bob and Claudia asked us to go deeper on the consequences of the Supreme Court overturning the Chevron doctrine.

Adam said please cover women and the environment.

What issues are you most interested in having us cover?

Let us know by sending us a written or audio message at comments@loe.org.

And please include a daytime phone number where we can reach you to verify your submission.

[MUSIC: Pinetop Perkins with Ann Rabson, “Careless Love” on Ladies Man, by Ledbetter, M.C. Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Shanzay Asif, Paloma Beltran, Kayla Bradley, Josh Croom, Karen Elterman, Daniela Fahria, Swayam Gagneja, Sommer Heyman, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Nana Mohammed, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Andrew Skerritt, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari.

DOERING: Jake Rego engineered our show. Allison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at loe.org, Apple Podcasts, and YouTube Music, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at @livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments@loe.org.

I’m Jenni Doering

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth