August 16, 2024

Air Date: August 16, 2024

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

How to Make Your Home More Wildfire-Safe

View the page for this story

When a wildfire powered by extreme heat and drought nears a neighborhood, all it takes is a single spark to send homes up in flames. John Fernandez is a professor of architecture at MIT and joins Host Jenni Doering to share some steps homeowners and renters alike can take to reduce that risk. (10:44)

Land Back for the Yurok Tribe

View the page for this story

On the northern California coast the Yurok tribe is getting 125 acres of its stolen land back thanks to an historic partnership between the National Park Service, California State Parks, and Save the Redwoods League. Chairman of the Yurok Tribe Joseph L James joins Host Jenni Doering to describe how the land will help nurture Yurok cultural traditions. (09:43)

The Crochet Coral Reef

View the page for this story

To raise awareness about the threats facing coral reefs, crafters everywhere are picking up their crochet hooks and contributing to a worldwide “Crochet Coral Reef.” Host Paloma Beltran spoke with Alyssa Velazquez, the curator of the Pittsburgh Satellite Reef at the Carnegie Museum of Art about what it’s like to stand inside the exhibit and how it came together. (11:03)

Wild Girls: How the Outdoors Shaped the Women Who Challenged a Nation

View the page for this story

To kick off Women’s History Month, we take a look at the history of women outdoors in America. From abolitionist Harriet Tubman to novelist Louisa May Alcott, some of the country’s most important women trailblazers shared a connection with the natural world in their girlhood. According to author Tiya Miles in her book Wild Girls: How the Outdoors Shaped the Women Who Challenged a Nation, this time spent in the outdoors prepared these women to become pioneers in their fields. She joins Host Paloma Beltran for more. (15:52)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

240816 Transcript

HOSTS: Paloma Beltran, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Tiya Miles

REPORTERS:

BELTRAN: From PRX this is Living on Earth

(THEME)

I’m Paloma Beltran

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

Native Americans win back stolen land in California

JAMES: It means healing. Healing for myself, healing for our people, knowing how far we have come as indigenous people. And when I see this piece of property and a village coming back with the Yurok ancestral territory, it makes my heart feel good.

BELTRAN: Also, an eco-illusion of a coral reef created with crochet.

VELAZQUEZ: A coral colony found its way out of the Gulf of Mexico through the Mississippi converged as a group along the Ohio, swam the Allegheny, or the Monongahela River, depending on which one they wanted to swim, and they just started growing in our galleries for our visitors near and far.

BELTRAN: Those stories and more, this week on Living on Earth — stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

How to Make Your Home More Wildfire-Safe

The wildland urban interface, or the transition zone between unoccupied land and human development, is especially vulnerable to forest fires. (Photo: Bureau of Land Management, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BELTRAN: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is an encore edition of Living on Earth. I’m Paloma Beltran.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering. More people than ever live in what’s called the Wildland-Urban interface, where forests and human settlements converge. Meanwhile, intense heat and drought driven by climate change are fueling extreme wildfires like those seen this summer across the Western US and Canada, and last year on the Hawaiian island of Maui. And when a forest fire gets out of control, all it takes is a single spark to send a home up in flames. But there are steps that homeowners and renters alike can take to reduce that risk and hopefully save their homes. John Fernandez is a professor of architecture at MIT who directs the Environmental Solutions Initiative there and he’s here to share some of these tips.

Welcome to Living on Earth!

FERNANDEZ: Nice to be with you.

DOERING: So what are some things that people who rent their house or maybe can't completely renovate their house can do to prepare for a fire?

FERNANDEZ: So there are a few things that you can do. And the most important thing is to reduce the fuel that's available between your house and the beginning of the forest, reducing the amount of objects that could ignite. That includes outdoor furniture, any plant material, so this is referred to as ladder fuel. So the material that would ignite and then lead to igniting larger plant material, and then eventually, you know, a tree that's right next to the house. And in fact, the fire in Hawaii was driven once it got into neighborhoods, by the prevalence of invasive grasses that are quite combustible and quite dense in their biomass and spread fire very, very quickly. So certainly not parking vehicles that have, you know, gas tanks, and that includes ATVs, motorcycles, cars, removing those from the space between the house and the forest edge is really important. So you can do a lot in terms of reducing fuel. And that goes a very, very long way, because it's really that fuel that acts as a bridge between a large forest fire and the house itself.

DOERING: And what are some other things that renters who don't necessarily have control over their home could do?

Reducing “ladder fuel” available between a house and the forest’s edge, such as outdoor furniture and plant material, is one of the most effective ways to protect against fire. (Photo: Marianne, Pexels)

FERNANDEZ: Yeah, so a very simple and effective thing that renters can do to reduce the possibility of fire from radiant heat, first of all, radiant heat will transfer through glass. And so if you have a very intensive wildfire, and it has to be really, really intense and close to the building, that radiant heat will transfer through windows and will ignite drapes, and furniture and other combustible materials close to that window. So a really simple thing to do is to open the drapes, make sure that it's not adjacent to the glass, and then any furniture that can be moved towards the center of the room and away from windows will reduce the possibility that that furniture will ignite spontaneously.

DOERING: So those are some great things that people can do maybe if they're renting a house. What are some materials decisions and structural decisions that homeowners who are maybe like making bigger changes to their house could make that might help protect against wildfire?

FERNANDEZ: So certainly, if you have design decision over the house, then it's you know, reducing the combustibility of the exterior facing of the house. So any wood material, so wood siding, shingles, will be susceptible to ignition compared to any material that has a cement base. So there are products that are like wood siding, they can be shingles or siding, or even large panels, that are cementitious, they have cement, and they're composed of some cellulose fiber but not enough to combust, that is much more resistant to fires. Certainly metal panel to reflect the heat and also non combustible. And the roofing material. Again, the same goes for roofing materials. A metal roof is preferable to anything else. But if you can't afford that, it is a little bit more expensive, non combustible tiles. And just inform oneself about the fire rating of those materials. A few other things one can do is you know, many house fires start because embers are driven into the house, either underneath the house. So the crawlspace is a real weak link in many houses. You can have a house that's completely clad in metal, but if the crawlspace is open, and then the underside of the crawlspace are wood joists, and then you get embers that are blown into that space, then those embers are going to lead to ignition of those joists in the crawlspace. So lining a crawlspace with a material, a latticework, a metal latticework, some kind of wire that keeps those embers from being driven below the house is really important. And then sealing any vents. So again, putting some kind of screening or wiring over vents. Those are decisions that a homeowner can make, that are reasonable to make, if you're concerned about being too close to the forest edge. If you can be further than 30 feet, if you can push the forest back, thin the forest back, a hundred foot buffer is a rule of thumb best practice, but a lot of situations don't allow that.

Residents can also move cars, motorcycles, and other vehicles with gas tanks as far away from the forest as possible. (Photo: Erik Mclean, Pexels)

DOERING: So these are some great ways that homeowners and renters can take action to reduce their fire risk. But of course wildfires that are so catastrophic are becoming more and more common. How can we get at the root of this crisis in the first place?

FERNANDEZ: Yeah, it's a great question. You know, we're in an era in which the kinds of decisions that are made in planning and development of residential neighborhoods and new towns needs to be rethought. The wildland urban interface is a much riskier place today than it was even just five years ago, and certainly ten years ago. So I think at the highest level, states and counties, certainly the federal government, needs to play a role in advising, and in some cases, limiting the kind of development that would continue to increase the number of houses, the number of, of people living in the wildland urban interface, who are at risk. Especially of massive fires, those that are just completely not controllable, they're absolutely runaway fires, and nothing can be done when they reach a neighborhood or a group of houses. We really do need to start thinking about planning in the geological epoch that we've entered into, the Anthropocene, of uncertainty and extreme events. In the actual planning of the development itself, and the layout of streets and the placing of houses, we need to design with wildfires in mind from day one. So the kind of landscaping that is planned for, you know, using other types of materials than plants to landscape with, gravel, tiles, again, from the inception of the design of the development.

Even moving furniture away from windows acts as a precaution. When a wildfire is very close, radiant heat can ignite flammable objects through glass. (Photo: Curtis Adams, Pexels)

DOERING: Professor, it's well known that trees and other plants in neighborhoods actually really help reduce the extreme heat that we're seeing in this era of climate change. But it sounds like those can also be a liability in terms of wildfire risk. How can we balance those two needs?

FERNANDEZ: Yeah, that's a really good point. It's a trade off. It is important to be able to shade especially hard surfaces to reduce the amount of heat that's absorbed by concrete, asphalt, as well as the fact that small trees, shrubs and other plant materials also are, of course, cycling water through them, and therefore, can be sources of evaporative cooling. And so a general cooling effect on the microclimate is important. It's particularly important in very dense urban environments. So where you have tall buildings, lots of air conditioning, lots of impermeable surface, roads and sidewalks, it's important to have as much tree cover as possible, so urban tree canopy. In a small town or a development within a forest, the forest itself is providing a lot of cooling to that area. And so I think it's a trade off between limiting the amount of fuel that's available to a fire that may enter into a neighborhood. Also managing those plants so that any dead branches, dead shrubs are cleared away. But it's going to be a trade off. And I think people should be really smart about the density of plant material to limit the fuel available for a fire.

DOERING: How hopeful are you about being able to reduce these risks so that people can live safely in the wildland urban interface?

Homeowners can consider more fire-resistant external materials, like metal roofs. (Photo: Brent Moore, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

FERNANDEZ: So for most fires, which are not the massive runaway fires, in wildland urban interface situations, you know, they are fires that can be managed. There's a lot we've already talked about that the homeowner, and the neighborhood can do to protect from the various ways in which materials ignite. So I am hopeful that we can do much, much better, and in doing much better, likely reduce the kinds of situations we've seen where neighborhoods are completely overrun, and residents have absolutely no option but to flee. Having said that, I am concerned that there is still an increasing number of people willing and interested to live in these places. And the deeper you go into the forest, the more problematic the situation is. So I think there does need to be a reckoning in society generally, but also in terms of the way in which the federal and local governments really contend with these situations and try to nudge development towards situations that are safer. But again, we need to shift our perspective from thinking about our present as more like the past, than it will be like the future. And the future is all about climate change. And the future is already here.

DOERING: John Fernandez is a Professor of Architecture at MIT and directs the MIT Environmental Solutions Initiative. Thank you so much.

FERNANDEZ: Thank you.

Related links:

- What is the wildland urban interface?

- Resources for preparing for wildfires

- Protecting your home

- More on preparing your home

- “Nature” Journal article: The Global Wildland Urban Interface

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Georgii” on Fornax, Blue Dot Studios 2021]

BELTRAN: Just ahead, the Yurok tribe is getting back ancestral lands on the California coast.

Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailorsforthesea.org.

[MUSIC: Fela Kuti, “Beasts of No Nation” on Beasts of No Nation, by Fela Kuti, Knitting Factory Records]

Land Back for the Yurok Tribe

(From left) Save the Redwoods League President and CEO Sam Hodder, Redwood National and State Parks Superintendent Steven Mietz, Yurok Chairman Joseph L. James, and California State Parks North Coast Redwoods Superintendent Victor Bjelajac sign the landmark agreement at ‘O Rew. (Photo: Matt Mais, Yurok Tribe)

BELTRAN: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Paloma Beltran.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

Over the last few centuries Native Americans have endured genocide, land theft, and attempts to erase their very cultures. But they are still here, and although the past can’t be changed, there is some healing now underway. On the northern California coast the Yurok tribe is getting some of its stolen land back thanks to an historic partnership.

The National Park Service, California State Parks, and Save the Redwoods League have agreed to transfer 125 acres of ancestral lands back into the hands of the tribe by 2026. For thousands of years the Yurok have lived near the mouth of the Klamath River, where the plentiful salmon nourished them and have been invoked in dance and music.

[“NEYPUY REK’WOY” SONG BY James Gensaw Sr.]

DOERING: This song called Neypuy Rek’Woy translates to “I went down to the mouth of the Klamath and caught a lot of salmon.”

[“NEYPUY REK’WOY” SONG]

DOERING: The place that the Yurok tribe is getting back is called O’ Rew in the Yurok language and includes habitat for young coho and chinook salmon. Joining me now is Joseph L. James, Chairman of the Yurok tribe. Chairman James, welcome to Living on Earth!

The 125-acre ‘O Rew property, part of traditional Yurok lands, used to be a mill site. (Photo: Matt Mais, Yurok Tribe)

JAMES: Thank you, glad to be here to talk about a historical moment for the Yurok tribe and its people.

DOERING: So first, Chairman James, can you tell me a bit about your people, the Yurok tribe, and your traditional lands? What are some of the core values of your culture?

JAMES: We're the largest populated tribe in the state of California. Our Yurok reservation is located in two counties, Humboldt and Del Norte county, up here in northern California along the Klamath River, just south of the Oregon border. We're river people. The Klamath River is our life way. We're a fishing tribe. So we're very grateful and appreciative of what the land and the river provides for us. Salmon and fishing, it's not just a food, it's our culture. It's our way of life as people.

Yurok children at play. The Yurok Tribe is the largest Tribe in the state of California, with over 6400 enrolled members. (Photo: Matt Mais, Yurok Tribe)

DOERING: And tell me more, please, about this place that we're talking about here, the 'O Rew land. You know, Save the Redwoods League is involved in this land back, so there must be redwoods there. I remember going to that Northern California coast a long time ago and it's very lush, rainy a lot of the time, but that makes it so prolific and there's so much nature and wildlife there. Can you describe that a little bit for us?

Tribal members in Yurok adornments. The Yurok Tribe plans to build a traditional village at the ‘O Rew site, where their community can gather for ceremonies and other cultural activities. (Photo: Matt Mais, Yurok Tribe)

JAMES: This property of 125 acres used to be a mill site, you know, where they decked back in the day-old growth logs and the large second old growth logs, specifically redwood. It's one of the southern areas from our reservation. It's a gateway into the redwoods. We have used redwoods for our ways of housing and lodging. We use our redwoods for our dugout canoes for traveling on the river. We also have streams running through the property along the highway. We have beaver there, we have small juvenile salmon, we have coho there. So, we're really excited to have our piece of property come back to the Yurok tribe, it's an old village site for us. It's exciting times.

DOERING: And by the way, what does 'O Rew mean in your language?

JAMES: It's the name of the village and location. A number of Yurok people have come from villages along the Klamath River and along the north coast. And so again, it's just our place of origin, where we come from.

DOERING: How do the Yurok people want to transform this piece of land that will be returned to you in 2026? What are your plans?

The Yurok people have been involved in restoring this area for over a decade. They plan to continue this work when the land is transferred to them in 2026. (Photo: Matt Mais, Yurok tribe)

JAMES: What we'll have is a visitor center here on the property, we'll also have a cultural center there, where we'll showcase our materials that we have used, whether it's making for boats, whether it's materials we gather for making baskets. So, we'll have our cultural items there that are appropriate to share. And then we'll also have a traditional village there that will be used by our tribal citizens. You know, we continue to dance, we continue to have our ceremonies, we continue to pray and continue to gather. We're looking forward to showcasing this with our young men, our young women and our adults, and a place to come, to gather, to continue that traditional practice. Also, this area, we have trail systems and networks of trails that we use for our ways of travel. And so, we're gonna include a network of trail systems there, using our Yurok language, using traditional knowledge of way showing and interpretive signage, plants, animals, what has the Yurok tribe since the beginning of time utilized these resources for, from a traditional perspective, not from a Western science perspective. That's what I'm so also proud of, the land not just coming back to us, but as first peoples, we get to share that knowledge and experience of what the work we have been doing since the beginning of time as people.

The Yurok Tribe has released 11 California condors in their ancestral areas. (Photo: Matt Mais, Yurok Tribe)

DOERING: So even though there has been logging of redwoods and other trees in this area, to what extent has the forest been able to grow back over time and with your help as well?

JAMES: Yeah, the Yurok tribe has been involved in this rehabbing the area to its original state for last 10 years. I'll start along the stream, the work that we've been doing, improving that stream habitat for our young juvenile fish to return, putting root wads in the streams, and also planting new trees along the stream bed to provide shade and canopy. It's exciting that we're doing the great work we're doing, improving habitat and salmon for future generations to come. You've got elk on the property. We just reintroduced the California condor. It's been 100 years since the California condors come back home to Yurok country. Now we have eleven flying California condors, probably about maybe 10 miles from this location. It's gonna take time, it's going to take time to bring the piece of property back to its original state, but we're fully invested in it. And we're able to have the help with our partners of Save the Redwoods, the California State Parks, and Redwood National Park. Our values and missions align. And we're continuing to continue that great work moving forward.

Elk roam the ‘O Rew area. (Photo: Matt Mais, Yurok tribe)

DOERING: Yeah, and this is a historic partnership with Redwood National Park, California State Parks and Save the Redwoods League working with the Yurok tribe on this land management. How have you collaborated with these folks in the past and how do you hope to grow that bond in the future?

JAMES: The Yurok tribe has a long-standing relationship with all three of them. The Yurok tribe has been working with the California state park system, you know they're located in the Yurok tribe's ancestral territory, so we do a lot of work with them, through trails improvements, through our cultural projects. You know, Redwood National Park is also located in the Yurok tribe's ancestral territory. So, the same model there, we've been working with the Redwood National Park regarding trails, maintenance. Save the Redwoods, you know, within the last 12, 13 years. They purchased this property in 2013. They are aware it was in the Yurok ancestral territory; they reached out to us. And, you know, we just had that conversation, and we've just grown over the years. And how you get to that trust is just sitting at the table in the room and growing that bond. Doesn't happen overnight, doesn't happen over, over one year. We're not looking to build trust for short term, we're looking to build for long term. And that's what you have here. And when I look at that, I've got a private organization, I've got a federal organization, and I've got a California state organization, giving land back to the Yurok tribe, right? You let that sink in. We all aligned and through discussion, partnership and trust, and collaboration, we are transferring 125 acres back to the ownership of the Yurok tribe. So, we're really proud of that.

A Yurok child holds a wooden carving of a salmon. Salmon and fishing are an integral part of the Yurok culture. (Photo: Matt Mais)

DOERING: Chairman James, what is this return of the 'O Rew land mean for the Yurok people?

JAMES: It means healing. Healing for myself, healing for our people, and now we got to heal the land and the property. It means excitement, it means very proud, privileged, and honored to have this piece of property come back in the hands of Yurok. Knowing how far we have come through the state of California, even across the nation, as indigenous people. How far our ancestors have paved the way to get to this point, knowing our people had to get sent to boarding schools, knowing their language at one point tried to wipe our language away. It wasn't successful. We're still here today practicing our culture, our traditions. And when I see this piece of property, in a village coming back with the Yurok ancestral territory, it makes my heart feel good. But also at the same time, we've got a lot of work yet to do. This is just one piece of property that we have.

The Yurok people will steward the land alongside their partners, Save the Redwoods League, California State Parks, and the National Park Service. (Photo: Matt Mais, Yurok Tribe)

DOERING: We've heard in recent years about this movement for land back in North America. How do you hope that this project and this land transfer might kind of help ignite that and transfer into other traditional lands?

JAMES: We look at this partnership, the way we've come together, it's not just for us. It's for all of Indian country. It's for all of us to to share, this model is for us to share. And again, it's a first of its kind here in our neck of the woods, up here in northern California. So, it's truly a historical moment for our land to come home, gives not just us hope, but gives others hope.

DOERING: Joseph L. James is Chairman of the Yurok tribe. Thank you so much, Chairman James.

JAMES: Thank you for having me on the show.

Related links:

- Yurok Tribe | “Save the Redwoods League, the Yurok Tribe, and Park Partners Sign Historic Agreement to Return Tribal Land”

- Learn more about the Yurok Tribe

- Living on Earth | “Replanting the Klamath River”

[“NEYPUY REK’WOY” SONG BY James Gensaw Sr.]

The Crochet Coral Reef

Alyssa Velazquez, the curator at the Carnegie Museum of Art, organized the Pittsburgh Satellite Reef by color to mimic the way water filters visible light. (Photo: Sean Eaton, Courtesy of Carnegie Museum of Art)

BELTRAN: Coral reefs are in trouble. The upper layers of the oceans absorb most of the warming and around a third of the carbon dioxide emissions from the climate crisis, making the water hotter and more acidic. These conditions are leading to coral bleaching and making it harder for corals to grow. Back in 2005, sisters Christine and Margaret Wertheim, founders of the Institute for Figuring, learned about the threats facing coral reefs. And they felt inspired to pick up their crochet hooks. They got to work making corals of all different shapes and colors, and with the help of many other crafters and museums their project has grown into a worldwide Crochet Coral Reef with around 50 “satellite reefs.” One of those is on display until 2025 at The Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The project brought crochet workshops to diverse communities around Pittsburgh and collected contributions from nearly 300 crafters. Here to talk to us about the project is Alyssa Velazquez, who led the Pittsburgh Satellite Reef as a curator at the Carnegie Museum of Art. Hi Alyssa, and welcome to the show!

VELAZQUEZ: Thank you. I'm so excited to be here.

The Pittsburgh Satellite Reef combines layered “frilly cabbage leaves” with cylindrical structures to mimic actual coral reefs. (Photo: Sean Eaton, Courtesy of Carnegie Museum of Art)

BELTRAN: We're really happy to have you. So if someone was walking through the Pittsburgh Satellite Reef exhibit, what would they see?

VELAZQUEZ: The Pittsburgh Satellite Reef is on the second floor of our hall of sculpture along the balcony with this decorative iron railing that visitors can walk around to view the marble sculptures. There's this little U-shaped gallery. If you enter the gallery, you travel along a curved and glassed-in display case. If you ever been to an aquarium, you might recall a similar space with low lighting and almost floor-to-ceiling glass panels in front of you. And so behind that glass is a large-scale wooly archipelago, chromatically organized to represent how colors filter through water. In other words, as light passes through a great distance of water, color is selectively absorbed by the water. So for the installation, all the hot or warm colors, those pinks, those reds, those yellows are at the top. And as your eye moves down the 2D wall pieces and rests on the floor of the case to roam over the 3D coral sculptures, you're left with blues, and purples, and greens. So they're all growing out of the space that's painted a rich plum, purple color to better offset the multicolored yarn. And to create the illusion that a coral colony found its way out of the Gulf of Mexico through the Mississippi, converged as a group along the Ohio, swam the Allegheny or the Monongahela River, depending on which one they wanted to swim, and they just started growing in our galleries for our visitors near and far. Which was one of the reasons why we felt the Carnegie Museum of Art was a great fit for this project in a city known for those three rivers, Ohio, Allegheny, Monongahela, and those waterways have a trickle effect, literally and pardon the pun, but on the ocean acidification and coral health.

The Carnegie Museum of Art brought together 281 artists to make the Pittsburgh Satellite Reef. (Photo: Sean Eaton, Courtesy of Carnegie Museum of Art)

BELTRAN: Sounds absolutely beautiful. You know, coral reefs are often referred to as the rainforest of the sea. They can be huge, and they support approximately 25% of all marine species. As a curator, how did you try and convey the grandiosity of this diverse ecosystem?

VELAZQUEZ: As a curator, I knew that for the piece itself to really shine, we needed to get inventive with our display strategies. And one of the things that was working in our favor was the space itself, the fact that it was a boxed-in aquarium just waiting to be filled with specimen-like objects. I started looking at lots of pictures of home aquariums, as well as public aquariums. And they all have somewhat of a purple, blue, green tinge to them, which is where we came up with the background color. And then within the coral pieces that we started receiving from community members, wanting them to dictate a lot of the design. And so when thinking of 2D elements that we would mount on the wall, that was because a lot of the corals that were being generated in these workshops were flat, or what I would lovingly term frilly cabbage leaves. Then so those have more presence when you're able to lay them down and build on top of each other, and how much more presence would they have, if you lay them down, build them on top of each other, and then turn them upright and mount them on a wall. And so then you create a 3D effect that's coming directly at you from the back of the case, reaching out to the glass and in some cases, to give greater that effect of rogue corals growing in the space, some of the corals touch the glass. And that was really important for us to create it. And then in addition to those 2D elements, having 3D sculptures on the ground, so that you have a diversity of visitors that can come in from various ages, and that there is something on everyone's eye level to really catch their intrigue, and make them look in amazement at where they are, both like literally and physically within the space.

BELTRAN: So also the little people could see the exhibit and live it.

VELAZQUEZ: Yes.

Coral reefs around the world are threatened by the climate crisis and plastic pollution. (Photo: bryceguy72, DeviantArt, CC BY-NC-ND 3.0)

BELTRAN: It sounds like there's such a variety of different forms in this exhibit. Like layered cabbage leaves.

VELAZQUEZ: Right, so for the cabbage-leaf-shaped, what they call hyperbolic planes or the hyperbolic corals that are flat, we layered them on top of each other, or in some cases, to create dimensionality, especially on the 2D wall sculptures, I would condense them, you could say almost in a tulip-like shape, and then would stuff them into various crevices to create a sense of growing out of and blooming. So there were some more three-dimensional shapes. If you think of tubers that are very iconic of coral formations on ocean floors, those sometimes were given additional rigidity with cardboard, or we did fill them with the stuffing that are in teddy bears.

BELTRAN: What types of materials did people use to make these corals?

VELAZQUEZ: The material used to make the corals are varied. They are from simple weighted thread, to cassette tapes, to VHS's, to water bottles, to wire. It all depended on the crocheter's comfortability with a hook. And so if you look at the coral reef, you'll see some shiny bits, and that might be a little bit of a reflective cassette tape. Or you'll see some sparkly bits, and that might be a unique type of yarn that's very delicate and thin and has some metallic elements. Or you might see some really warm, earthy greens and reds, and that's coming from some basic medium-weighted yarns for beginners.

BELTRAN: So I have yet to live the exhibit, but I've been told that it includes acrylic nails, what is the significance of that?

The Pittsburgh Satellite Reef brought together people from across the generations to work on a unique crochet project. (Photo: Sean Eaton, Courtesy of Carnegie Museum of Art)

VELAZQUEZ: Yes, so as the exhibition space, I described that U-shaped gallery, that's the primary space that we display the coral reef, but we also within that hall of sculpture off of the balcony, one of the ways of accessing that gallery space is by a staircase. And when you're going up the staircase, on that second floor, there's a little niche with glass covering over it. And for that niche, we wanted to put some corals in. And I saw that we were developing an exhibition design that was very bombastic in the main exhibition space. And for this small case, I really wanted to explore some of the stereotypes from contemporary art museums, one of them being the white cube. So rather than painting it purple, like the main exhibition space, we left it white. And rather than filling it with as many corals as possible, I selected two corals. And so I created a space in which you could have a small coral and a large branch coral within a white box. And on the floor of this white box, where these corals seem to be growing out of, is a bed of white acrylic nails. As a material, they're plastic. A lot of the acidification in the oceans is due to our single-use and non-degradable plastic waste, but also this discussion about primarily the makers of the Pittsburgh Satellite Reef, but also most of the satellite reefs, part of the Worldwide Crochet Project do identify as women.

BELTRAN: Why is having art that relates to the environment so important?

Velazquez created the feeling that the corals are alive and spreading by having them push up against the glass. (Photo: Sean Eaton, Courtesy of Carnegie Museum of Art)

VELAZQUEZ: I think you need exhibitions about the environment, about your local both land and water health, to inspire a pride of place, which Pittsburgh definitely has. We have a lot of Pittsburgh pride, and with good reason, but pride of place of how that fits in within the international discourse. How what we do here does matter. And that's both the metaphorical statement and the literal physical statement that what we do to these three rivers, they do have a cause and effect on the larger world. And that can be both negative and it can now be positive with this exhibition. We hope that individuals who participated in the project, they'll bring their family and loved ones from far and wide, to not just showcase themselves as being an artist, but to showcase what one person can do to inspire really positive change. I think that's what's so beautiful about having this exhibition.

BELTRAN: Alyssa Velazquez is a curator at the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh and was in charge of developing the Pittsburgh Satellite Reef. Thank you so much for joining us.

VELAZQUEZ: Thank you for having me. It's been a pleasure.

Related links:

- Read more about the Pittsburgh Satellite Reef.

- Understand the Institute of Figuring’s mission.

- Learn about coral bleaching.

- Watch Margert Wertheim talk about the coral reef project.

- Learn more about UpstreamPgh a nonprofit that works to secure equitable, just access to clean, natural water for all and collaborated on the "Crochet Coral Reef".

- Learn more "Crochet Coral Reef" collaborator Kid Ewe Knot

[MUSIC: We are the Fossils. “None the Wiser – Instrumental” on Instrumental Indie-Folk, Vol.2, alexrainbirdRecords]

DOERING: After the break, how time in the outdoors shaped some famous women trail blazers. That’s coming right up on Living on Earth. Stay tuned!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[Joe Hicks, “Pieces – Instrumental” on Instrumental Indie-Folk, Vol.2, alexrainbirdRecords]

Wild Girls: How the Outdoors Shaped the Women Who Challenged a Nation

Wild Girls: How the Outdoors Shaped the Women Who Challenged A Nation (Photo: Courtesy of Tiya Miles)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran. During the 19th century, the ability to spend time in nature helped free some girls from restrictive social norms and turned them into pioneering women. Abolitionist Harriet Tubman, novelist Louisa May Alcott, Native American writer Zitkála-Šá, and farmworkers’ champion Dolores Huerta all shared a connection to the natural world in their girlhoods. For more on these trail blazers, we turn to historian Tiya Miles. In her book Wild Girls: How the Outdoors Shaped the Women who Challenged a Nation, she reveals how playing and working outside in their youth prepared these women to lead the way towards gender equality, abolition, and more. Tiya recently joined me to share their stories and I asked her to start by reading a passage from her introduction.

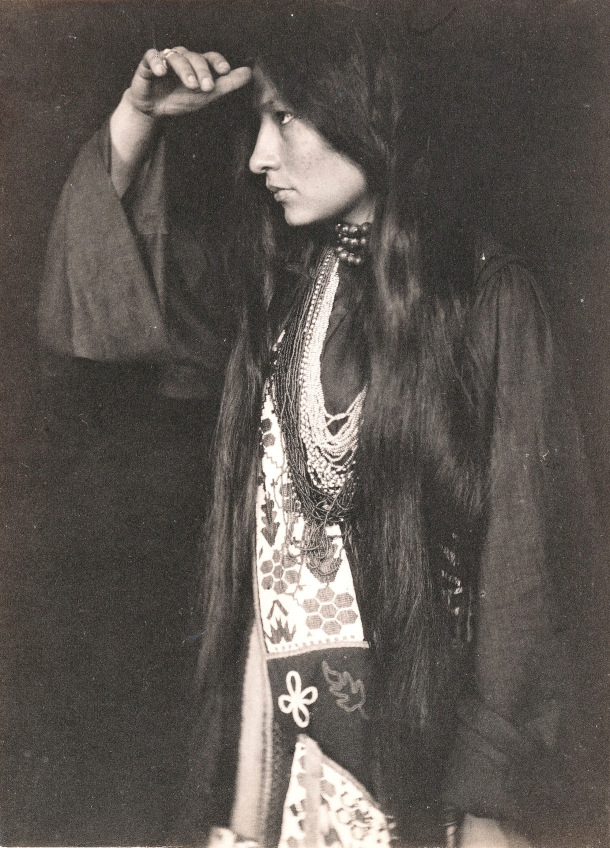

Zitkála-Šá, also known as Gertrude Simmons, was a member of the Yankton Dakota tribe. After a childhood spent in the wilderness, Zitkála-Šá became an author, musician, and activist. (Photo: Gertrude Käsebier, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

MILES: From the micro scale of a single tree to the macro scale of the forest, spaces in nature have been meaningful to the visionary lives of American girls. Girl outsiders became trailblazers in their communities and in American culture, writ large. Time in the outdoors ignited girls’ critical awareness, fed their self-knowledge, charged their imaginations, built their capacity for resilience, and bestowed moments of inner peace that steadied their spirits and tumultuous times. The stories pressed into this book, like wildflower petals, will show how time spent outside shape the character of girls who later changed the country.

BELTRAN: Thank you. Please talk to me about the complicated social context in which these wild girls grew up in amongst the outdoors.

MILES: Well, most of the book is describing experiences that take place in the 19th century. And this was a period of extreme restriction, constriction, oppression for many different populations of girls living on these lands. It was a period as we know, of enslavement. It was a time when boarding schools, organized and funded by the federal governments were created to compel Native American, quote, education. It was a time when girls of any class at any background were expected to know their place in a sense, when it came to gendered organizations of society. So girls were supposed to be quiet, still, pure, virtuous, and obedient really, across the board in the context of American civilization.

American writer, nurse, human rights activist, abolitionist, political activist and freedom fighter Harriet Tubman (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Library of Congress, Public Domain)

BELTRAN: A moment in history that you point to is that of the Leonid Meteor shower that took place in 1833. Where thousands of meteors were seen across North America. Harriet Tubman observed that event. Can you tell us more about Harriet her story and what she witnessed that day.

MILES: Harriet Tubman was enslaved in the US South, Tubman was born in Maryland, probably in the early to mid 1820s. And she grew up in the dire-ist of circumstances. She was constantly being separated from the mother she loved, from her siblings and her father, because the man who owned her mother, and her mother's children, including Harriet Tubman, would lease them out to bring in income. So Tubman was often as a very young girl, separated from her family, alone, desperate, afraid. And as she got to become a little older and a little bolder, in part because of her experience outside, Tubman learned how to run away from the people who were leasing or renting her, and to find her mother, who was on another farm or another plantation.

BELTRAN: Tremendous bravery.

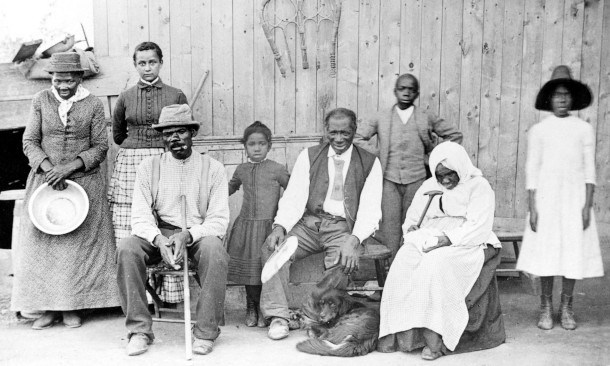

Harriet Tubman (far left) alongside members of her family and several boarders who lived in her home. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

MILES: I know, I know, it's incredible and so much courage. And one of these nights when Tubman ran away, just briefly, temporarily, to visit her mother. She was there with her brother, and they were inside the cabin where her mother lived. And her brother would stand outside at the door of the cabin, to watch for the patrollers. And these are people who would basically police the roads to look for enslaved people who might be out of their so-called rightful places without permission. And they would return these enslaved people, and they could exact terrible punishments. So Harriet Tubman as a girl, probably around the age of a tween, so a preteen was with her mother visiting and her brother was standing guard by the door, and her brother, all of a sudden shouted, "come out, come out and look at the stars". And Harriet Tubman, who at that time was known by the nickname of Minty, came outside and joined her brother. And she looked up and she saw what she later described as just an uncountable number of stars that were shooting across the sky. Harriet Tubman later said that she thought that moment could have been Judgment Day, because it was so incredible, so miraculous, to see what looked like, you know, millions or billions zillions of stars just raining down onto the earth. Well Tubman wasn't the only enslaved girl to witness this site and many other enslaved girls and boys and children saw this and remembered the story of what they often described as the night the stars fell. And in Harriet Tubman's world, and the world of enslaved girls and enslaved people, this shower seemed to carry a message. And the message was that God could possibly pass judgment on the people who are mistreating others on the earth, God could possibly pass judgment on enslavers, because God could bring the sky down in a shower of stars.

BELTRAN: How did Harriet Tubman’s experience outside help her gain the tools she needed to lead people to freedom?

Tiya Miles is the Michael Garvey Professor of History and Radcliffe Alumnae Professor at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University and author of Wild Girls: How the Outdoors Shaped the Women Who Challenged A Nation. (Photo: Tobi Hollander)

MILES: Spending time in nature gave Harriet Tubman psychological tools as well as the practical tools for the freedom fighter that she would become. She talked about how she was a neglected weed as a child, and these are her words. This is something that really caught my attention when I was thinking about how to interpret her life story, because it tells us that Tubman was an observer of nature. She was someone who thought nature, thought about herself through the language of nature. But it also tells us that Tubman recognized the way in which she was being mistreated as a child and she also associated herself with a kind of living thing that is incredibly tough and resilient. Tubman was a very religious woman. She believed that God was against slavery and at the same time she felt that it may have been ordained by God that she was placed outside during her teenage years to learn how to navigate the woods and learned she did. She learned about the woods, she learned how the waters flowed in the woods, she learned how to read the sky, she learned about the different animals that would be with her in the woods and when she made her escape, which would be her fine escape from slavery as a young woman she applied all of those skills. For a decade of her life following that she helped other people in the very same way, moving through those woods that she has become a companion of.

BELTRAN: And you also profiled the famous author Louisa May Alcott as one of these Wild Girls. How did Louisa's connection to nature inspire her literary work?

Louisa May Alcott was an American novelist, short story writer, and poet best known for writing the novel Little Women. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

MILES: Well Louisa May Alcott is a historical figure who I never really expected to research and write about Paloma. She's somebody who I read when I was a teenager, I read "Little Women" I think probably in high school or around that time and I vaguely recall enjoying the novel. But I had never thought that I would return to her. I worked on this book during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic and there was one particular weekend when my kids and I were just feeling stir crazy in the house. We needed to get out and for some reason it popped into my head "let's go to Louisa May Alcott's Orchard House". This is a historic site in Concord, Massachusetts not too far from where we live. And as I was at her home and reading about her it sort of clicked that she would've been walking these hills, she would've been planting in this garden, she would've been in a landscape where not too far away there was the very famous Walden Pond. And so I thought let me just look into this and it turns out Louisa May Alcott was a perfect figure to include in this book. I really did not know that Paloma, I had not idea the extent to which her connection to the outdoors, her sort of psychological and emotional connection, was born out of her childhood and the things she loved to do. The way she perceived herself and not just in the novel "Little Women" where we see it all over the place in the character Joe March who is a quote "tomboy". Well Louisa May Alcott was also a "tomboy" those were the words she used to describe herself and she was somebody that would say, that she didn't even want to play with a kid unless they could climb a tree, unless they liked to play with spiders the way she did. Her favorite reading spot was this old kind of wheel barrel out in the yard, she loved to go tearing across the fields. She loved to hang out with actually older men including some of the famous philosophers that we know of from Concord, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau. Louisa May Alcott I learned through my research had a really interesting way of thinking about herself. She wrote that she felt much more like a boy or a wild deer or a horse than a girl. She felt like one of these beings, these other kinds of beings who could be outside, could run outside, who could express themselves with these sort of dramatic movements all of which was supposed to be off limits for girls. I mean there's this really interesting detail that I have to slip in there…

BELTRAN: Please do!

MILES: Alcott says that when she was a girl, her mother actually tied her to the sofa to try to keep her in the house. I mean, that is, I think, the perfect symbolic image for the expectations of certain girls, especially middle class, Euro-American girls living in New England at this time. That they were supposed to be in the parlor, behaving properly, being dainty, being quiet, being pretty, being seen and not heard. But that was not who Louisa May Alcott was, she refused to be that girl. And actually, when her family moved to the country, which was Concord, her mother just seems to have given in maybe given up perhaps actually recognize and embrace the kind of kid she had. And she said Louisa May Alcott go run, and she allowed the Louisa to explore the outdoors.

Louisa May Alcott often roamed the famous Walden Pond, a lake in Concord, Massachusetts, in the United States. (Photo by Bill Illot, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BELTRAN: Talk to me about how the multiracial spaces near Boston and Walden Pond. How did that help shape Louisa May Alcott, her writing and her spirit?

MILES: Louisa May Alcott was an unusual kid. She was an unusual girl for her family, for her society and for her time. And one time when she was doing her walkabouts, she fell into Frog Pond. And she was actually in great danger in this moment. She might have drowned. Alcott reports that it was a black boy who saved her. It was a black boy who jumped in and helped her to get out of Frog Pond. And she says from that moment, she became an abolitionist. One of the things that we see through Alcott's story and also the other stories that I tell in the book is outdoor spaces seem to make a way for people of different racial categorizations, different sex and gender categorizations, different class categorizations to come together, because they are not as heavily separated and segregated, and surveilled and policed as some of these interior spaces. So Alcott might not have come across a black boy who had that kind of freedom of movement in the town homes and country homes of her family, but the outside of the park, she did encounter him, and that encounter changed her life in more than one way. It may have actually saved her life and it certainly began a transformation in her thinking.

Louisa May Alcott’s historic orchard house. That is where Louisa wrote Little Women in 1868 and where the novel was set. (Photo: Tiya Miles)

BELTRAN: Tiya, what do you hope readers take away from your book and these stories?

MILES: I have heard form a number of readers, a number of women readers that the most meaningful thing to them about this book is that it reminded them of their girlhoods, it reminded them of who they were when they loved to be outside, when they loved to run through the woods to explore their neighborhoods. And it has reminded them that they want to be those same people. They want to embrace those girlhood adventures again. I so appreciate hearing that. And I would also hope that people take away a sense of inspiration about their own lives. I really do wish that people would see the examples in this book as models for what it is we can do to take care of the earth, top take care of these faces in nature and also to ensure that people have equal access to them.

BELTRAN: Tiya Miles is a Professor of History at Harvard and author of “Wild Girls: How The Outdoors Shaped the Woman who Challenged the Nation”. Tiya thank you for joining us.

MILES: I enjoyed it so much. Thanks, Paloma.

Related links:

- Learn more about Tiya Miles

- Literary Hub | “How America’s Natural Beauty Called Generations of Women to Action”

- Purchase Tiya Miles' book "Wild Girls: How the Outdoors Shaped the Women Who Challenged a Nation" (Affiliate link supports LOE & indie bookstores)

[MUSIC: Mary Lou Williams, “My Blue Heaven” on Mary Lou Williams Presents Black Christ of the Andes, Smithsonian Folkways Recordings]

DOERING: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Shanzay Asif, Kayla Bradley, Josh Croom, Karen Elterman, Daniela Faria, Swayam Gagneja, Sommer Heyman, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Nana Mohammed, Aynsley O'Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari.

BELTRAN: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Allison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and YouTube Music, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments at loe dot org. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Paloma Beltran.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering. Thanks for listening!

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth