September 6, 2024

Air Date: September 6, 2024

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Bright Future for Western Solar

View the page for this story

The Bureau of Land Management is updating its master plan for developing solar energy on BLM lands in the West, to help the US meet ambitious clean energy targets. Gregg DeBie is an attorney with the Wilderness Society and joins Host Aynsley O’Neill to explain how the proposed plan aims to reduce barriers to solar by highlighting “previously disturbed” lands and automatically excluding critical habitat. (11:19)

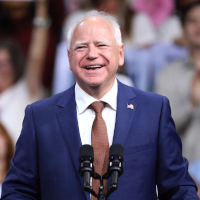

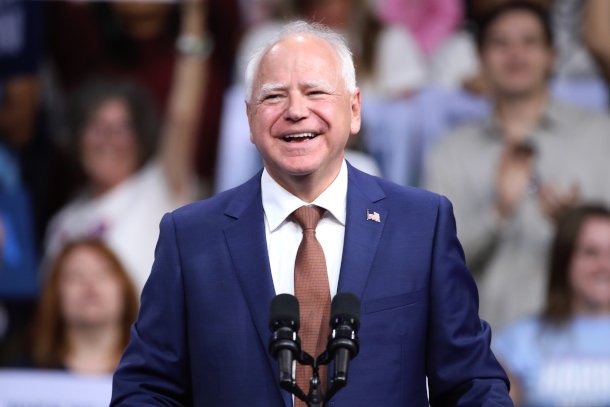

Tim Walz's Climate Record

/ Kristoffer TigueView the page for this story

Tim Walz, the running mate of Democratic presidential nominee Kamala Harris, has signed climate legislation as Minnesota Governor and supported regenerative agriculture bills as a Congressman. Inside Climate News reporter Kristoffer Tigue joins Hosts Aynsley O’Neill and Jenni Doering to discuss the praise Walz has received for his climate work as well as some criticism over his history of supporting the ethanol industry and oil pipelines. (08:18)

Can the Planet Afford Gas in New Homes?

/ Dharna NoorView the page for this story

Some new affordable homes built by Habitat for Humanity are being fitted with solar panels and labeled as “zero-net energy”, meaning they are supposed to produce as much or more energy than they use. But as reporter Dharna Noor of the Guardian explains to Host Jenni Doering, some of these homes include gas appliances, canceling out many of the climate benefits. (12:25)

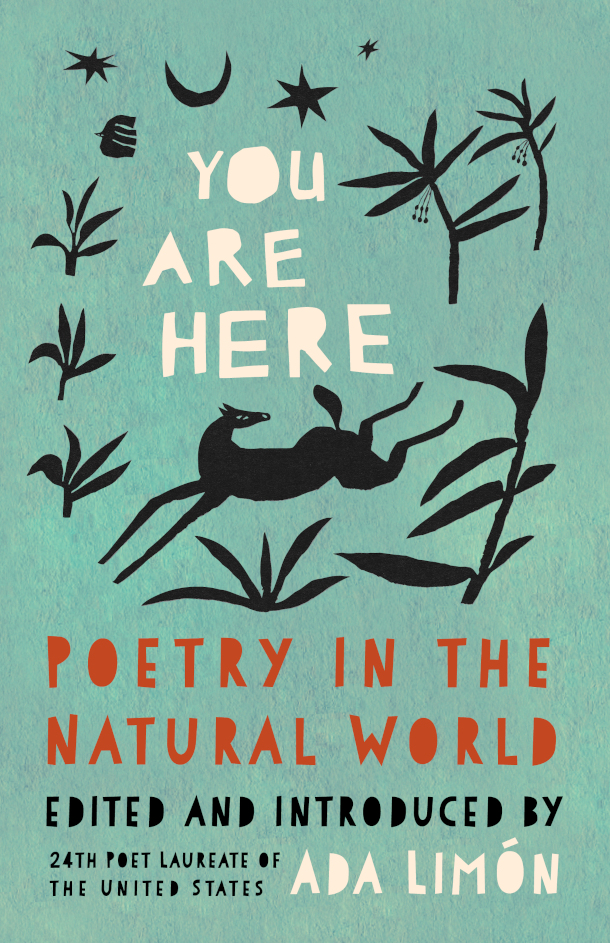

Poems for a "New Nature" with Ada Limón

View the page for this story

Poetry can be up to the seemingly impossible task of capturing ecological loss, wild joy, and empathy for other species on this embattled planet. US Poet Laureate Ada Limón joins Host Jenni Doering to share poems from her new anthology, You Are Here: Poetry in the Natural World and discuss why she believes we need a new kind of nature poetry for the new nature amid the climate crisis. (15:37)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

240906 Transcript

HOSTS: Jenni Doering, Aynsley O’Neill

GUESTS: Gregg DeBie, Ada Limón, Dharna Noor, Kristoffer Tigue

[THEME]

DOERING: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

DOERING: I’m Jenni Doering

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

New affordable homes are being built with gas appliances even as they’re billed as “zero net energy.”

NOOR: There’s no reason to pit the interests of people in having affordable homes against the interests of people in having a livable climate, especially when there’s tons of research that show that low-income people in the US and elsewhere are more vulnerable to the effects of the climate crisis.

DOERING: Also, when that crisis is too much to bear, poetry can help guide us.

LIMÓN: We worry about hope, I think. We worry that we're naive for it. And I think this is a poem that's saying, searching for the light and leaning into hope is not naive, but it can be hard won.

DOERING: We’ll have those stories and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Bright Future for Western Solar

The proposed updated Western Solar Plan would extend solar development guidance to five additional western states: Idaho, Wyoming, Montana, Washington, and Oregon. (Photo: Tom Brewster Photography)

DOERING: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

Public lands in the United States have historically been used for a variety of purposes, ranging from wildlife habitat to recreation to fossil fuel development. In fact, as of 2022, about 23 million acres of public lands were under lease for oil and gas extraction. But public lands are also important for building out renewable energy, like solar. And the federal Bureau of Land Management, or BLM, the largest landowner in the country, is now in the process of bringing its plans to develop solar energy in the Western US up to date. So, this August BLM released a proposal for how it would update this Western Solar plan, which is expected to be finalized by the end of the year. The update earmarks around 32 million acres for possible solar development. Gregg DeBie is a Senior Staff Attorney for The Wilderness Society and he’s here to walk us through what this new plan might mean for the west. Welcome to Living on Earth, Gregg!

DEBIE: Thank you. Great to be here, Aynsley.

O'NEILL: Gregg, from what I understand, the Bureau of Land Management first wrote a plan for Western solar development way back in 2012. And this proposal seeks to update that plan. So, what major changes to solar development in the West are being proposed with this?

DEBIE: Yeah, I'd say right off the top, the biggest change is BLM is broadening the geographic scope of the plan. The original 2012 plan created a blueprint for solar development in the six southwestern states, which at that time was where most solar development was expected to occur, so California, Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, and Nevada, and Colorado. New technologies, such as photovoltaic panel technology, which converts sunlight directly into energy, has really taken the place of the old technology in 2012, which was concentrated solar farms. And that old technology required more sunlight, it required flatter land. So, BLM at the time really just focused on the six southwestern states where most of the sun was and most of the flatter land was. Now that there is new technologies, BLM determined that it needed to expand the plan to cover the northern Rocky states and the Pacific Northwestern states as well. So, Montana, Wyoming, Idaho, Washington, Oregon. Previously, solar development could still occur in those five other states, but it was happening in a more ad hoc fashion and without the guidance that's set forth in this plan.

O'NEILL: And what is the sort of goal of these updates, you know? What is the Bureau of Land Management really hoping to accomplish here?

From the outset, the plan excludes about 130 million acres of public lands from solar development to protect migration corridors, critical habitat, monuments, and wilderness areas. (Photo: Oregon Department of Agriculture, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DEBIE: From my perspective, based on what BLM has indicated in the plan itself and from its public statements, BLM, for one, is responding to the clean energy goals set by Congress in the Energy Act of 2020 and in various executive orders issued by the Biden Administration. Those goals are 25 gigawatts of clean energy on public lands by 2025 which BLM has already met and surpassed that goal earlier this year. And then there's a goal of a carbon free electricity sector by 2035, and net zero emissions economy by 2050. So, there's a lot of work to do to accomplish those last two goals. And this updated solar plan hopefully will help put us on the path to a clean energy transition. And then, you know, just generally speaking, the primary goal of the plan is really just to determine which lands should be open or closed to solar applications based on the presence of resource conflicts, the concerns of local communities and tribal nations, and just to determine where solar is not appropriate and where it might be suitable.

O'NEILL: So, walk me through this term, "previously disturbed land." What does that mean in this context?

BLM worked with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to identify and exclude critical habitat and connectivity lands for endangered species, like the Mojave Desert Tortoise, from solar development. (Photo: Bureau of Land Management, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DEBIE: Yeah, "previously disturbed." It's a little bit of a vague concept, and the way it's laid out in the plan is a little wonky, but BLM considers lands to be previously disturbed, where the soils or the vegetation have been altered from historical reference conditions, so where humans have caused a disturbance on the land. So, think roads, buildings and other infrastructure. And the question of previously disturbed lands is important, and it arises here because BLM identified lands as available to solar application if they are either within 15 miles of existing or planned transmission lines, or if they're outside that 15 mile buffer, if a solar application is on what qualifies as "previously disturbed lands," then BLM will accept and process that application and consider whether to approve or deny that project.

O'NEILL: So, it sounds like the idea is to steer projects away from a sort of pristine habitat. In what other ways does the proposal account for wilderness and wildlife protection?

Only about 2% of the 32 million acres open for solar development across 11 western states, or 700,000 acres, is projected to be developed to meet national solar energy needs by 2045. Those 700,000 acres could power tens of millions of homes. (Photo: Kevin Dooley, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DEBIE: Yeah, a plan of this size covering 11 states can never be perfect. And no plan of this size and scope ever is. But we do think it's a critical first step that BLM needed to undertake to help the transition to a clean energy economy. And we do think BLM did some things right to protect wildlife and wilderness and public lands generally. Right off the bat, the plan prohibits solar development on over 130 million acres of the most important public lands that the agency knew immediately would never be suitable for utility scale solar development, so places like monuments and wilderness areas, critical habitat, etc, are excluded from solar development. And then you know more specifically, BLM did things to protect wildlife migration corridors, which are critical for biodiversity and the long-term health of wildlife populations. They're essential for subsistence lifestyles and recreational economies and western communities. BLM also worked with the Fish and Wildlife Service to map specific areas that are important to about 40 specific species that are listed under the Endangered Species Act, so it identified, for example, important habitat connectivity lands for the Mojave Desert tortoise. And now we're committed to ensuring that BLM successfully implements the solar plan in a manner that avoids the most conflicts and addresses the concerns of local communities and tribal nations.

O'NEILL: So, Gregg, if you tally it all up, there's something like 160 million acres of public lands that are managed by BLM across these 11 western states. And this plan takes about, you know, 32 million of those acres and leaves them open to solar development. But that still sounds like a lot to me. I mean, I can't imagine that that's all going to be chock block full of solar projects. So how much of that land is BLM expecting to actually be developed for these solar projects?

DEBIE: Yeah, that, I'm glad you asked that question. This is really important. Of course, the 32 million acre figure grabs the headlines, and it's shocking when you first see that number, but it's important to realize that not all of those lands will be covered in solar panels. So, BLM looked at a couple studies from the Department of Energy and the National Renewable Energy Laboratory to estimate that only about 700,000 acres, and that's still a large amount, but again, remember, this is spread out over 11 western states, about 700,000 acres of lands will be needed to meet our solar energy needs by the year 2045, so about 20 years from now. And these 700,000 acres represents barely 2% of the 32 million acres that BLM has determined might be suitable for solar development, so 98% of these lands, even under an aggressive build out scenario, will not be developed with solar projects.

O'NEILL: Gregg, why is this update so important? What is going to come out of it?

Gregg DeBie is a Senior Staff Attorney for The Wilderness Society. (Photo: Courtesy of Gregg DeBie)

DEBIE: So, climate change is the most pressing environmental and social justice issue of our time. We think the science is unequivocal that greenhouse gas emissions are causing climate change effects, and that immediate action is necessary to avert the worst impacts. And public lands offer some of the best renewable energy sources to allow us to quickly transition to a clean energy economy. Using the formula that BLM relies on, these 700,000 acres could potentially support over 93,000 megawatts of solar power, or 93 gigawatts. This is enough to power tens of millions of homes. I think it's over 30 million homes or so. So, we would still need a mix of other renewable energy sources, like wind and geothermal and others, but this plan will go a long way to meeting our clean energy goals. We think it's a thoughtful, comprehensive plan that is consistent with what we call a "smart from the start" approach to renewable energy development, where careful, thoughtful planning that considers the input of local communities and tribes in the beginning, will lead to faster deployment of solar energy in the end.

O'NEILL: Gregg DeBie is a Senior Staff Attorney for the Wilderness Society. Gregg, thank you so much for joining me today.

DEBIE: Thank you. It was great to be here.

Related links:

- Bureau of Land Management | “Bureau of Land Management Releases proposed Western Solar Plan”

- Read the proposed updated plan here

- Read more about The Wilderness Society

[MUSIC: The Django Reinhardt Festival, “Pretext” on Gypsy Swing! Dorado Schmitt/Angelo Debarre/James Carter/Babik Reinhardt/Samson Schmidt/Serge Camps, By B. Reinhardt, Kind of Blue Records]

DOERING: Coming up, we’ll take a look at the climate and environment record of Democratic Vice-Presidential Candidate Tim Walz. Stay tuned to Living on Earth!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Gary Burton/Julian Lage, “Of the Woods” on NPR Tiny Desk Concert, by Gary Burton, NPR Music]

Tim Walz's Climate Record

Minnesota Governor Tim Walz at a Harris-Walz campaign rally in Arizona. (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

ONEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

Jenni, as you know alongside Democratic nominee Kamala Harris is her running mate, Tim Walz. And all eyes have been on him and his record in the month or so since he was tapped as vice presidential candidate.

DOERING: Yeah Aynsley, Walz has been Minnesota’s governor since 2019, and for over a decade before that he represented the state’s historically red first district as a Democrat.

O’NEILL: And I think he’s also pretty famous for giving off this sort of “Midwestern dad”, everyman energy.

DOERING: That’s right, he was a high school social studies teacher, a football coach, and he served in the National Guard. So yeah, I would say “Coach Walz” fits the bill.

O’NEILL: But putting his midwestern dad credentials aside, we’re here to take a look at his record on climate and environment with journalist Kristoffer Tigue from our media partner, Inside Climate News.

DOERING: And Kristoffer joins us from Minnesota. Welcome to Living on Earth!

TIGUE: Hi Jenni and Aynsley, thanks for having me.

DOERING: So, let’s start with Tim Walz’ time as governor, what’s his reputation there?

TIGUE: Well, Walz is considered a climate champion among advocates for the progressive policies he passed in this state, including a 2023 bill he signed that requires Minnesota utilities to produce 100% of their electricity from carbon-free sources by 2040. He made a point of mentioning that climate win in his State of the State speech earlier this year:

WALZ: We struck a blow against climate change, putting Minnesota on a path to 100% clean energy by 2040 and leading the nation.

TIGUE: Now that law is on par with those in states that have traditionally led on climate action like California and New York. He also signed a bill that same year that was compared to the Inflation Reduction Act for its investments in a green future.

O’NEILL: What kind of investments would those be?

TIGUE: The act invested around $2 billion dollars into rebates for electric vehicles and heat pumps, incentives for schools to install solar, and funding for habitat restoration. It also created regulations for PFAS, or forever chemicals, and initiated efforts to improve agricultural practices. Governor Walz also signed legislation to streamline clean energy development that supporters say will shave about 9 months off the whole process.

DOERING: Wow. Infrastructure, EVs, and clean energy, that does sound a lot like the Inflation Reduction Act. Now, Kristoffer, since Walz is from the Midwest, what kind of relationship with the ag industry does he have?

Governor Tim Walz (left) on the Kruger Family Farm in Minnesota. Walz is seen as close to the agricultural industry because of his support for regenerative agriculture and ethanol production. (Photo: Office of Office of Governor Tim Walz & Lt. Governor Peggy Flanagan, Flickr, public domain)

TIGUE: Yeah, that’s a good question. Agriculture is a huge deal in the Midwest, which produces about a quarter of the nation’s food each year, and Walz is friendly with the ag industry, to say the least - both big ag and small-scale farmers alike. When he was in Congress, Walz served on the Agriculture Committee, where he supported bills that helped small-scale farmers compete with factory farms and incentivized farmers to adopt regenerative practices that improved soil health. Now, that’s good for climate since it allows the land to absorb more carbon dioxide.

O’NEILL: Yeah, we heard similar things from Sean Carroll of the Minnesota-based Land Stewardship Action.* He says Walz has carried similar policies forward into the Minnesota statehouse.

CARROLL: As governor in Minnesota, Governor Walz and our legislature have put historic investments into soil health programs, creating an emerging farmer office, developing a down payment assistance program to help farmers buy land. And these are policies that address the root systemic change we need in agriculture. Keep more farmers on the land and allow the farmers who are stewarding the land to earn a fair wage for their work.

TIGUE: And of course, Walz understands that connection between ag and climate.

Here he is in 2020.

WALZ: “Everybody wants that better future for their children. Everybody, I think, wants to leave something that they can be proud of. And I think it's going back to finding those sweet spots, for example, around climate change. Again, I said I represented one of the largest agricultural districts, number two in pork production, number two in Turkey's, all of those things that you would think are associated with rural America and that there might not be that emphasis. These are people that are deeply connected to the land, deeply concerned about sustainability. So, when I first went to Congress and started talking about addressing climate change, while yes, it's an existential threat, was also an incredible economic driver and a legacy issue for our children.

DOERING: Well, and Governor Walz has gotten a lot of press for his efforts to use those Midwestern food resources to improve the lives of children now. He’s supported “farm to school” programs and in 2023 he signed into law a free school breakfast and lunch guarantee.

From sustainable agriculture to clean energy, Minnesota is a consistent leader on climate solutions.

— Governor Tim Walz (@GovTimWalz) August 14, 2024

Thanks to a new $200 million grant from the EPA, we’re cutting climate pollution from our food systems – reducing our carbon footprint and ensuring a healthier, safer Minnesota. pic.twitter.com/eJ6B22m4LY

TIGUE: Yeah, but Jenni there’s a flip side to the ag industry support as well. Environmentalists have criticized Walz for his support of ethanol, which is a corn-based fuel that’s added to gasoline. Forty percent of America’s corn goes to producing ethanol.

Supporters say it’s more environmentally friendly than gasoline alone, but some research has shown otherwise. So many climate activists believe ethanol isn’t good for the environment at all and, similarly to fossil fuels, needs to be phased out.

But Walz has never asserted such a thing, and it seems unlikely he would.

O’NEILL: Ok, sounds like he’s walking a fine line there.

TIGUE: Definitely.

DOERING: Well, Kristoffer, aside from agriculture issues, what other pushback has Walz received about his record?

TIGUE: Sure, many climate activists and indigenous groups have criticized Walz for supporting tar sands oil pipelines. Specifically, he supported the Keystone XL pipeline as a congressman and, as governor, he allowed the completion of the Line 3 pipeline, which runs from Canada to Wisconsin by way of Minnesota.

DOERING: Yeah, both pretty controversial pipelines. So, Kristoffer, what does this all mean for the future of the democratic party? What kinds of policy actions in terms of agriculture and environment is a Harris-Walz administration likely to take if they win this November?

TIGUE: Well, it’s hard to say but it’s certainly strategically important for Harris to have a Vice President who can connect with the needs of rural America while also pushing for strong climate policies, both in agriculture and beyond. Like Biden in his last two years, we’re seeing Harris take a more moderate approach to climate change policy. Remember that as a presidential candidate in 2020, she supported banning fracking but has since switched her position. Walz walks that line too, especially when it comes to his support of certain fossil fuel infrastructure and the ag industry. For now, it appears that the two are adopting the platform Biden was running on and both Harris and Walz have refrained from mentioning climate policy in their public appearances since the start of their campaign together.

Kristoffer Tigue is a journalist with our media partner, Inside Climate News. (Photo: Courtesy of Kristoffer Tigue)

O’NEILL: Yeah, I know that when the spotlight was on Walz at the Democratic National Convention, I was crossing my fingers for a mention of climate or environment in his speech, but we didn’t get too lucky there, did we?

TIGUE: Yeah, that’s right. That was a bit of a theme for this year’s DNC. The environment only really made an appearance in the speech once - when Walz was criticizing his opponents.

WALZ: When Republicans use the word freedom, they mean that the government should be free to invade your doctor’s office, corporations free to pollute your air and water, and banks free to take advantage of customers. But when we Democrats talk about freedom, we mean the freedom to make a better life for yourself and the people that you love. [BIG CHEERS]

TIGUE: His speech was really more pep than policy - complete with several of his former football players appearing on stage to cheer him on. And it’s been pretty similar messaging since the convention wrapped up - which is not much. But still, top Democrats seem to be okay with this. Jay Inslee, the Democratic governor of Washington and a well-known climate hawk told the New York Times that he doesn’t mind that Harris and Walz are refraining from speaking about climate change. Those democrats believe it’s more important to draw a distinction between a Harris-Walz ticket and a second term for former President Trump.

DOERING: Well, we’ll be eager to see what else we hear on climate and environment from the Harris-Walz campaign in these very short weeks before the election.

O’NEILL: Kristoffer Tigue is a journalist with our media partner, Inside Climate News.

Kristoffer, thanks so much for joining us today!

DOERING: Thanks, Kristoffer.

TIGUE: Thank you both.

*Editor's Note: We incorrectly identified Sean Carroll when this story first ran. He is Policy Director for Land Stewardship Action, not Land Stewardship Project. We regret the error.

Related links:

- Inside Climate News | “Climate Advocates Rally Behind Walz as Harris’ VP Pick”

- Kristoffer Tigue at Inside Climate News

[MUSIC: Frank Sinatra, “I'm Gonna Sit Right Down (And Write Myself A Letter) (Remastered 1998)” on Swing Easy, Capitol Records]

Can the Planet Afford Gas in New Homes?

Volunteers raise a wall into place during the Habitat for Humanity Earth Day 2009 in Oakland, California. (Photo: Sandia National Laboratories, Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0).

DOERING: Rooftop solar, weatherization and efficient appliances can lower the overall carbon footprint of homes and even make them “zero-net energy”, meaning they produce as much or more energy than they use. And local affiliates of the nonprofit Habitat for Humanity are building such homes intended to give people affordable housing while also helping the planet. But appliances powered by fossil fuels are being installed in some of these homes, canceling out many of the climate benefits and potentially harming the health of the people living there. Dharna Noor reported on this for the Guardian and joins me now. Welcome to Living on Earth!

NOOR: Thanks so much for having me. It's exciting to be here.

DOERING: What are zero net energy homes, and how do the homes featured in your investigation claim to qualify?

NOOR: Yeah, it's interesting. So, zero net energy homes are essentially supposed to be homes that create more power than they use. So, in this case, they're homes that are outfitted with solar panels on their roofs. They're meticulously sort of weatherized and insulated to ensure that no unnecessary energy is being used to boost efficiency. But the actual appliances in the homes can be powered by anything in Zero Net Energy Homes, and in the story that I wrote about the case of utilities partnering with Habitat for Humanity chapters, it's actually gas that is powering many of these appliances, such as stoves and furnaces and water heaters.

DOERING: So how realistic is the expectation that these homes can actually achieve zero net energy use when gas is being used in these homes?

NOOR: So yeah, it's a great question, and there's sort of two issues here. One of them is that, as you're sort of suggesting, there is some evidence that in at least one case, one of these so-called dual fuel homes, that's a home that runs on gas for appliances but also is outfitted with solar panels, was not meeting that benchmark, but a fully electric one in the same sort of region was. That said there are certainly homes that have gas appliances in them that are meeting the zero net energy benchmark. But the bigger issue here is that even if they are producing more energy than they're using, they're still producing emissions, greenhouse gas emissions, planet warm and pollution. So simply producing power from solar panels on your rooftop does not actually cancel out the emissions from, say, your furnace or your stove if they run on gas. And there's another thing at play here too, which is that placing gas in homes is not only itself a source of emissions, but it actually sort of gives an excuse to continue producing gas. You know, pulling it out of the ground, extracting it, sending it through pipelines, distributing it to homes and homes that purport to be zero net energy, even if they do meet that benchmark, if they run with gas in them, they can sort of give city officials a message that, hey, we actually need to keep producing this planet heating fossil fuel to ensure that, you know, people have access to cooking appliances and warm air and warm water and things like this. So, while some of them actually do meet the benchmark there are some issues at play, I guess I'd say.

The “zero-net energy homes” built by Habitat for Humanity affiliates are meant to produce as much or more energy than they use, but the homes also come with gas appliances, canceling out many of the homes’ climate and energy benefits. Pictured above is a home from Habitat for Humanity’s Build-A-Thon site in Oakland, California. (Photo by Sandia National Laboratories. Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

DOERING: So, proponents of gas will say it is cleaner burning than, for example, like an oil powered furnace, which I used to have in an apartment. But what are the concerns when it comes to the emissions that can be produced from gas in homes?

NOOR: Yeah, the question of how clean gas is relative to other fossil fuels sort of depends who you ask, I guess. Industry interests have long claimed that gas is cleaner than oil and coal, you know, the other sort of main fossil fuels that we use. There's some evidence for that, but then there's other evidence that actually shows that if you take the methane emissions into account, it's actually more planet warming than coal from sort of extraction to use. So natural gas, as it's called by industry interests, is actually mostly made of methane, and that's a planet heating gas that is actually 80 times more planet warming than carbon dioxide in the short term. So, it's a pretty huge sort of contributor to fossil fuel use and to greenhouse gas emissions. So again, sort of depends what you ask how clean it is, but I think there's plenty of evidence that shows that industry interests have certainly been calling it a clean fuel, when, in fact, experts are very, very concerned about not only its effects on the climate, but also its effects on human health.

DOERING: So, explain, please, why some climate advocates are saying that this practice of putting gas into these so called Zero Net Energy Homes that this is a big public relations stunt. What's going on there?

NOOR: Yeah, I mean, it's something where I think the concerns of some of these climate advocates really bore out in my research. So, I talked to a guy named Itai Vardi. He works at the sort of watchdog group called Energy and Policy Institute that's really pro-electrification. And he basically said that the project of installing these so called zero-net-energy homes with Habitat for Humanity chapters by gas utilities, he said this project is a cynical PR stunt. And in fact, that seems like it was not just a sort of vibes-based analysis, I actually was able to obtain industry webinar recordings and other sort of internal documents that showed that that is basically the case. You know, during this one webinar that I watched from last year, there was a representative from the utility Atmos Energy that's created these zero-net-energy homes with Habitat chapters all over the US, and they said that these projects actually began as a response to the attempts to get gas out of buildings. So the first one of these projects was in Colorado, and he said, and this is a direct quote: "In Colorado, they are a little bit on the front lines, as far as some of efforts to maybe dissuade people from utilizing natural gas, and as such, that became the chosen site for our very first natural gas ZNE, that's a zero-net-energy home build". So essentially, what he's saying here is, hey, in Colorado, they're actually like getting some support to try to get gas out of homes. And so, we put this here intentionally to try to combat those efforts.

DOERING: By the way, Darna, where are these homes being built?

NOOR: So, these homes are in a lot of different places. Atmos Energy, which is a gas utility, launched the project again in Colorado in September 2021, and it since expanded it to a bunch of different places, Kentucky, Louisiana, Texas, Mississippi, Tennessee. And it also has new plans now to launch similar initiatives in Virginia and Kansas. And then there's a couple other utilities that have used a sort of similar model. There's national fuel that operates in the Northeast and then there's SoCalGas, which operates, of course, in Southern California. Nicor, which is another gas utility that operates specifically in Illinois, has also partnered with Habitat on zero net energy projects. So really, these are pretty pervasive in lots of different parts of the country.

Most Habitat for Humanity “net-zero energy homes” cater to low-income members of vulnerable communities, including people of color and veterans. Pictured above is the inside of a Habitat for Humanity house in Miami, Florida. (Photo: Blitz Build, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: Now Darna, there are studies that we've reported on Living on Earth that link gas stoves to poor indoor air quality and problems like asthma.

O'NEILL: Yes.

DOERING: To what extent do you think that those health impacts might be especially harmful for the low income and minority communities that this affordable housing is being built for?

NOOR: Yeah, this is such a good question, and it's something that really sort of concerned me when I learned about these projects. Experts have been warning for a really long time that gas appliances emit lots of toxic pollutants, including carcinogens. And as you're sort of saying, a recent slew of studies has linked gas stoves to specifically increased risk of childhood asthma, as well, as you know, things like chronic lung disease and a bunch of other health impacts. And you're right in sort of wondering about the specific effects on low-income people. There's plenty of research that shows that low-income people and people of color specifically may be at higher risk if they're exposed to these sort of toxins in their homes, because they might be more likely to have asthma and underlying respiratory issues already due to the sort of disproportionate exposure to environmental contaminants that we see in this country based on a very racist history of things like redlining and the way that highways have been built and things like this. So, it's a way that I think this project, sort of, you might say, adds insult to injury. Not only is it low-income people who are being used as the sort of excuse to place more gas in homes, but they themselves, via these projects, may also be getting exposed to harmful pollutants that could really harm their health and their children's health.

DOERING: Dharna, I understand there are some fully electric homes that Habitat for Humanity is building.

Dharna Noor reports on fossil fuels and climate for The Guardian US. (Photo: Courtesy of Dharna Noor)

NOOR: There are.

DOERING: So, to what extent could those serve as a model for future projects?

NOOR: Yeah, this is part of what's so interesting about the sort of Habitat model here. I spoke with Habitat International, and they said that they're certainly concerned about climate change. They purport to be a sort of climate leader, but they also said that they sort of leave it up to individual habitat chapters to decide what kinds of projects they're going to embark on and how they get their funding. But Habitat for Humanity’s affiliate in Cape Cod, Massachusetts, actually did build all electric homes in partnership with a public utility in Cape Cod. In 2021 it was actually rated the best rated habitat home in the nation in terms of efficiency. Another habitat affiliate in Massachusetts actually built another all electric, zero net energy home that won praise from the federal government. They did not partner with utility. And actually this year, the federal government announced $2 billion for a coalition of nonprofits, including Habitat for Humanity International and some sort of climate focused nonprofits. So, in essence, while there are habitat chapters that are partnering with gas utilities to put more gas into low income homes, Habitat International is actually embarking on this project to spend lots of money to build fully electric low-income housing. So certainly, I think that that provides a lot more evidence that we don't really need to put polluting fuels like gas in homes in order to ensure that people can afford them.

DOERING: So, looking at the big picture here, how important is safe and affordable climate-controlled housing in a world where extreme heat is creating dangerous conditions in cities?

NOOR: Yeah, I mean affordable housing is absolutely, of like, complete paramount importance, especially at a time when the climate crisis is getting so much worse. We see, for instance, that low-income homes are often more likely to be built in flood plains, the heat island effect, which means that places that have a lot of asphalt and paved areas kind of soak in more heat. That effect can mean that low-income people are much, much more exposed to dangerous temperatures, and also affordable housing can often be the housing that is kind of not kept up with very well. It can often be left to deteriorate, and that means that it's often much less efficient than housing that you know, sort of wealthier people are able to live in. So, it's really, really important to have affordable housing and also climate safe housing, and obviously, I applaud efforts to get people into safe, affordable homes. Again, though, just would venture to say that there's no reason to pit the interests of people in having affordable homes against the interests of people in having a livable climate, especially when there's tons and tons and tons of research, just mounds of research that show that low-income people in the US and elsewhere are more vulnerable to the effects of the climate crisis.

DOERING: Dharna Noor is the Fossil Fuels and Climate reporter for The Guardian US. Thank you so much for joining us today.

NOOR: Thanks for having me.

DOERING: Just a note on the comparison of methane versus carbon dioxide when it comes to how much they warm the planet. When methane is burned in a gas stove or furnace, most of it is converted to carbon dioxide, so it counts the same as any other molecule of CO2. Still, some of it does leak into the atmosphere between when it’s extracted and when it makes it to your stove, and that’s where the 80 times potency difference comes into effect.

Finally, when asked about its policy on gas in homes, Habitat for Humanity International provided a statement that reads in part: “Habitat International and our diverse network of Habitat affiliates and organizations – each an independent local non-profit – rely on a wide range of partners and home energy sources to help increase access to safe, decent, and affordable shelter. Some of those partnerships, including those cited in the Guardian article, seek climate-change solutions related to housing, and Habitat organizations continue to evaluate which ones are most effective.” You can read the full statement on the Living on Earth website, loe.org.

Statement from Habitat for Humanity International

“Habitat for Humanity’s vision is of a world where everyone has a decent place to live, but we cannot reach that vision alone. In the midst of a historic housing crisis in the United States and around the world, Habitat International and our diverse network of Habitat affiliates and organizations – each an independent local non-profit -- rely on a wide range of partners and home energy sources to help increase access to safe, decent, and affordable shelter. Some of those partnerships, including those cited in the Guardian article, seek climate-change solutions related to housing, and Habitat organizations continue to evaluate which ones are most effective. Whether through these partnerships in the U.S. or through our advocacy on housing and climate change globally, Habitat is confronting a complex and growing housing crisis so that more people have a decent place to call home.”

Related links:

- Read Dharna Noor’s investigation on The Guardian | “A New Project Promised Low-Income Families ‘Zero Net Energy Homes’ – but They Still Rely on Gas”

- Follow Dharna Noor on X

- StanfordReport | “Study Finds Combustion From Gas Stoves Can Raise Indoor Levels of Chemical Linked to a Higher Risk of Blood Cell Cancers”

- The Guardian | “Gas Stoves Making Indoor Air Up to Five Times Dirtier Than Outdoor Air, Report Finds”

- About Habitat for Humanity

- Energy News Network | “A St. Paul, Minnesota Habitat for Humanity Project Will Offer Affordable Housing Without Fossil Fuels”

- Learn more about Zero Energy Ready Homes

- Learn more about LEED-certified Homes

[MUSIC: Sultans of String, “Le Bisou” on Yalla Yalla!, by McKhool/Laliberte, Ontario Arts Council/Canada Council for the Arts]

O’NEILL: After the break, US Poet Laureate Ada Limón shares poems to help us connect with and grieve for a changing Earth. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Pete Siers Trio, “My Melancholy Baby” on Those Who Choose To Swing, by Lyrics by William Frawley/Music by Ernie Burnett]

Poems for a "New Nature" with Ada Limón

You Are Here: Poetry in the Natural World is a poetry collection edited by Ada Limón. (Photo: Courtesy of Milkweed)

O’NEILL: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

The environmental crises we are witnessing today can be so overwhelming, that it’s hard to fully capture in prose. But poetry is up to the task of conveying the complex emotions of ecological loss, wild joy, and empathy for other species on this embattled planet. You Are Here: Poetry in the Natural World is an anthology of poems collected by US Poet Laureate Ada Limón to challenge what we think we know about “nature poetry” in these changing times. Ada Limón joins us now. Welcome to Living on Earth!

LIMÓN: Thank you so much for having me. It's such a pleasure to be here.

DOERING: Well, it's a pleasure to have you. So, I have to say, this is a wonderful anthology. It's thought provoking. It's accessible too, though. What sparked this project for you?

LIMÓN: Every Poet Laureate is tasked by the Librarian of Congress to create a signature project, and I knew that I wanted to do something that would combine poetry and nature, so I wanted to make sure that I had a couple of different elements. One of the things was that I of course, wanted to celebrate the national parks and do something that felt like it was uplifting some of our protected spaces, but that felt like intentional nature, the nature that you plan for, the nature that you pack a bag for, the nature that in many ways, you pay for, because you're going in and you're going to either get a campground site or you're going to get a hotel. But I wanted the anthology, You Are Here: Poetry in the Natural World, to really be a counterbalance to the national parks project, so that we could also look at the everyday nature, the nature that's not necessarily intentional, but the nature that is all around us — the nature that we experience, whether it's in urban settings or in really beautiful, stunning locales. And that was really important to me. I wanted to make sure that every voice could be heard in this book. And I also wanted it to be very clear that no matter where you live, nature is everywhere, and that we are, ourselves, nature.

Ada Limón is the 24th Poet Laureate of the United States. (Photo: Ayna Lorenzo, Courtesy of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation)

DOERING: It's everywhere. You're right. And there's celebration in this book. You could maybe even call it worship of the natural world. There's also grieving for what's being lost to fires, floods, these things of the climate crisis. Talk to me about how poetry might help us all grapple with that grief.

LIMÓN: Thank you for that question, because I think that one of the reasons, I worked so hard on this project and support it with my whole body and soul is that I think we really needed a moment for a new nature poem, because we are living in a new nature. As the climate crisis deepens, worsens and we have more evidence of it every minute in our daily lives, it has felt like we can't return to the nature poem as a type of healing. Instead, we needed to turn to a nature poem that can include a type of grieving and can include a type of clear-eyed awareness of where we are, so that we might collectively move forward into some kind of action. And that's really what I thought poetry can do in this certain moment, is make space for that enormity of feeling, that range of feeling, which can certainly be wonder, awe, joy, the feel of ease, the feel of connectedness, the feel of, "I am not alone. In fact, I am instead a being connected to all things wondrous on the planet," and that's there. But I also wanted to make room for the space for solastalgia, for missing the place that we are right now, knowing it will change and shift. And I think poetry is a place that makes room for the entire spectrum of human emotion. And so, this was the project to pay homage to where we are right now, and You Are Here as the title also felt like you are here as a mantra in many ways.

DOERING: Is there any particular poem that speaks to sort of grappling with where we are at this moment?

LIMÓN: They're all doing different things, so I don't think there's one necessarily that's a call out, but I do love the "Reasons to Live" at the end by Ruth Awad, which is such a beautiful, stunning poem, which to me, really encompasses all of the ways in which we have to not only struggle with our existence on this planet and our connection to this planet, but also that we have to recommit to living here and recommit to this life in all its complexities. And I think that sometimes that can be very difficult, and so that recommitment feels really evident in that final poem.

DOERING: Ada, could you please read us that poem, "Reasons to Live" on page 145?

LIMÓN:

"Reasons to Live"

Because if you can survive

the violet night, you can survive

the next, and the fig tree will ache

with sweetness for you in sunlight that arrives

first at your window, quietly pawing

even when you can't stand it,

and you'll heavy the whining floorboards

of the house you filled with animals

as hurt and lost as you, and the bearded irises will form

fully in their roots, their golden manes

swaying with the want of spring —

live, live, live, live! —

one day you'll put your hands in the earth

and understand an afterlife isn't promised,

but the spray of scorpion grass keeps growing,

and the dogs will sing their whole bodies

in praise of you, and the redbuds will lay

down their pink crowns, and the rivers

will set their stones and ribbons

at your door if only

you'll let the world

soften you with its touching.

DOERING: I love that that's the last line in this book. "If only you'll let the world soften you with its touching."

LIMÓN: When I read this poem, I just knew it had to be the last poem of the book. I felt like, if there was one message, it was to be a receiver of the world. And I felt like Ruth's poem just made such a beautiful offering to really open us up to receiving the world.

DOERING: All right. Well, there's another poem that kind of speaks to me in a similar way, "Heliophilia," on page 133 by Aimee Nezhukumatathil.

“Heliophilia,” by Aimee Nezhukumatathil, is a poem that encourages readers to lean into joy. (Photo: Kreuzschnabel, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

LIMÓN:

"Heliophilia"

Desire to stay in the sun / love love of sunlight

Don't call it an affliction —

call it affection. I'd stay under

the sun all day, never hiding

under a copse of trees if I knew

I wouldn't burn, but isn't it

more accurate that I burn

for the sun? To be pulled to the light

is nothing to be ashamed of: look

at flowers, butterflies, seals lounging

on a rock. Rhubarb sings in dark gardens

but truth be told it sounds more like

a wet cracking and popping. I think

it secretly counts the hours till it can turn

towards the sun again. For me, the sun

has always been easy to love, as easy

as it is to love whatever small light

bees bestow on fallen leaves—easy

to love the light they give just before

they crawl into a honey-hungry sleep,

just before the first fall of snow.

DOERING: "Honey-hungry sleep." Beautiful. Ada, what stood out to you about this poem?

LIMÓN: To me, this idea of the rhubarb singing in the dark, and this idea of also that sometimes we feel shame that we want the light, and I feel like that's so important right now. I think that there's so oftentimes, as we know, our brains have the negativity bias that we are wired for per evolution, that we keep seeking out the danger, looking for the worry, following the anxiety, the trail of fear. And this is a poem that releases us to the light, that gives us the light that keeps saying, "Don't be ashamed to search for it, to lean into it." We worry about hope, I think. We worry that we're naive for it. And I think this is a poem that's saying, searching for the light and leaning into hope is not naive, but it can be hard won, and it is also our nature. Sometimes we lose track of that. We think it's our nature to go to the dark parts, to go to the worst-case scenario, but it is also our nature to seek out the light.

DOERING: You're the U.S. Poet Laureate. And the U.S. is a big country with a lot of different diverse cultures and subcultures, and this book features a lot of different voices in it. How would you say that these diverse perspectives build upon each other in You Are Here?

LIMÓN: For me, one of the things that's really important about this book is that it is representative, at least in a small way, of the many different landscapes and the many different voices that are writing today. Some of the poems are people who are deeply connected to nature, who felt deeply connected to nature their whole lives. And then some of the voices are from poets that are laughing that they don't ever know the names of trees. And I think that's really important too, because there's a way in which I can say, "Oh, yeah, I was raised in California, northern California. I have a deep connection with nature. It's always been the place that I go to for a type of healing, a type of solace and a type of peace." But there are a lot of folks that I know that are like, you know, “nature's where bad things happen. You know, nature is not the safe place, or nature has always been a white space, a place where I don't feel like I'm welcome, or I feel, in fact, my body might be harmed in some way.” And so, I wanted to make sure that all of those voices were heard in this book.

Eduardo C. Corral’s poem, “To a Blossoming Saguaro,” explores discusses the links between nature and politics. (Photo: Joyce Cory, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: Could we get you to read one more poem? It's "To a Blossoming Saguaro" by Eduardo C. Corral, on page 17.

LIMÓN:

"To a Blossoming Saguaro"

You have kin in Mexico.

Shooting you is called "cactus plugging."

Humidity & wind speed shape the path of a bullet.

Your shadow will outlive my father.

That's kind of comforting.

Ghost-faced bats pollinate your dog-eared flowers

which smell like wet rope, melon.

The sky is a century with no windows.

I say things like that. Sorry.

You have more rights than the undocumented:

I need a permit to uproot you.

Ofelia believes only rain can touch all of you.

My mother is my favorite immigrant.

After her? The sonnet.

DOERING: There's so much in such a short poem.

LIMÓN: Yeah, I think Eduardo C. Corral is a master of really condensing great, heightened emotion as well as transformative images in a short poem. And when he sent this, I was just blown away. And the saguaro is one of my favorite plants. To think of it as also something that has more rights than the undocumented is an incredible line. I think it gives a lot to think about when we think about this country and what we protect, and what we can get people to think of in terms of requiring safety and security. And I think this poem is both beautiful and absolutely true in its nature.

Ada Limón has always felt a deep connection to the natural world. In this anthology, she chose to feature poets from a range of perspectives. (Photo: Ayna Lorenzo, Courtesy of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation)

DOERING: What do you hope readers take away from this collection of poems?

LIMÓN: I have many hopes, and I can get really big with my hopes. If I could say, what do I really want readers to take away? I would say that we must save this planet. If we are writing toward it, offering something back like love, appreciation, affection, worry, tenderness, then doesn't that say we must collectively create a movement that speaks to the importance of this planet and the reciprocal nature of nature and ourselves? I would love for people to write their own poem, and that in that writing of their own poem that they might be able to create their own kind of reciprocity with the natural world they see out their window they see every day on the way to the bus stop, whatever it is that they have a relationship to. Even if they don't think of themselves as a poet or as a writer or even as an artist in any way, maybe it's time to start and offer something back. There's a hashtag. If they want to share a poem, they don't have to — private poems are just as important — but it's #youareherepoetry. But I would love for people to reimagine their own relationships to the landscape around them, and in doing so, maybe deepen their own connection to the planet and beyond that, maybe work towards ways in which we can address this really urgent moment on the planet.

DOERING: Ada Limón is the 24th Poet Laureate of the United States, and collected the poems in You Are Here: Poetry in the Natural World. Thank you so much, Ada.

LIMÓN: Thank you so much for having me. It's just such a pleasure to talk to you.

Related links:

- Support Living on Earth and local bookstores by purchasing You Are Here: Poetry in the Natural World here

- Learn more about the history of the Poet Laureate’s role

- Explore Ada Limón’s work

[MUSIC: Hank Mobley, “Soul Statio – Remastered 1999/Rudy Van Gelder Edition” on Soul Station, Blue Note Records]

DOERING: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Shanzay Asif, Paloma Beltran, Kayla Bradley, Josh Croom, Karen Elterman, Daniela Faria, Swayam Gagneja, Sommer Heyman, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Nana Mohammed, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari.

O’NEILL: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Allison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at loe.org, Apple Podcasts and YouTube Music, and you can write to us at comments at loe.org. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth