October 4, 2024

Air Date: October 4, 2024

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Disastrous Climate Wake Up

/ Abrahm LustgartenView the page for this story

Hurricane Helene brought devastating storm surge and winds to the Gulf Coast and deadly floods to the inland mountains of North Carolina. Journalist Abrahm Lustgarten is the author of On the Move: The Overheating Earth and the Uprooting of America and joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss the societal toll of repeated climate-fueled disasters and whether this latest super cyclone might prove a tipping point for greater climate awareness and action. (12:37)

Birdnote®: Here Come the Merlins

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

The Merlin is one of the world’s smallest falcons yet it’s something of a trailblazer. Rising global temperatures are forcing many species to head north, but as BirdNote®’s Mary McCann reports, these adaptive predators have begun to move south to occupy the abandoned homes of other avian migrants. (01:48)

Jill Stein for the Greens

View the page for this story

Physician Jill Stein, the 2024 Green Party nominee for US President, urges a much quicker phaseout of fossil fuels than either of her Republican or Democratic opponents appear willing to consider. Jill Stein joins Host Jenni Doering to lay out her vision for what she calls a “real” Green New Deal and to push back against claims by Democrats that voting for her in a swing state could hand victory to Donald Trump. (12:55)

Sudan's Climate and War Misery

View the page for this story

Millions of Sudanese people have fled armed conflict in recent months, only to face famine as well as floods and extreme heat worsened by climate change. Nisreen Elsaim is a young climate activist from Sudan who co-chaired the UN Secretary General’s first youth advisory group on climate change. She joins Host Steve Curwood to describe the harrowing conditions for Sudanese refugees and what gives her hope. (18:23)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

241004 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Nisreen Elsaim, Abrahm Lustgarten, Jill Stein

REPORTERS: Mary McCann

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

As floods ravage the US Southeast and Northeast Africa, there’s a call for a reckoning on the climate emergency.

ELSAIM: Does humanity have priorities? Or all humans are equal? I mean, this is the question that we need to keep asking ourselves.

DOERING: The climate, famine and displacement in war-torn Sudan.

CURWOOD: Also, a third-party voice on the upcoming presidential election.

STEIN: A democracy needs a moral compass. It needs a vision. It needs the idea that, we could have a climate that we could live in and green jobs that ensure no worker will be left behind.

CURWOOD: Green Party candidate Jill Stein and more, this week on Living on Earth—stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out in The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Disastrous Climate Wake Up

Hurricane Helene devastated towns as far inland as Asheville, NC. (Photo: Bill McMannis, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

It may be weeks and months and even years before we fully understand the catastrophic impact of the Super Hurricane, Helene. Still over water Helene first flattened many shoreside communities along the Gulf coast of Florida before it ripped ashore in North Florida and rampaged through five more states, leaving many in its path without working roads, power, food, and water. Helene’s huge size and speed are linked to increasingly hotter water in the Gulf of Mexico, and a stark reminder that with global heating, weather forecasts based on history are becoming poorer guides to present dangers. Hurricanes have usually weakened when they make landfall, but to the surprise of many, Helene’s impact was just as devastating in the inland mountains of western North Carolina as on the Gulf coast of Florida. Gargantuan amounts of moisture drenched hills and valleys of the region with water that had nowhere to go but down into homes, businesses, roads, and bridges along the swollen rivers and streams. As we record this broadcast, the death toll is nearing 200, with many others still missing, and the final numbers could be much higher. On the line now is Abrahm Lustgarten, journalist and author of “On the Move: The Overheating Earth and the Uprooting of America”. Abrahm, welcome back to Living on Earth.

LUSTGARTEN: Hi there. Thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: Abrahm, what role does climate denialism play in the wake of disasters like Hurricane Helene? I mean, to what extent can communities turn a blind eye here, continue to turn a blind eye here?

LUSTGARTEN: This is a difficult question for me to answer. I mean, I think politically, climate denialism will make it difficult for certain people in certain places to have a forthright conversation about what has just happened to their towns, to their homes, to their cities, and that's going to make a policy response or a decision about what kind of government response people expect, difficult to arrive at. On the other hand, my experience socially in talking to a lot of people through the course of my reporting is that there is an undeniable sense and a real consensus among all types of different political views that the environment around them is rapidly changing, and that is changing in disruptive ways. And I hear this in all sorts of ways. I hear from conservative homeowners on the coast of Florida that they were just surprised to see a flood coming again year after year, that they remember hurricanes from years past. And hurricanes are a normal part of living on the Gulf Coast, but they don't remember them being so destructive and so frequent and so that might not be a person who is politically supportive of the idea of climate change, but that is an acknowledgement of what we all see happening around us, which is that the present doesn't feel like it's matching the patterns of the past, and that the environmental change is something that people are concerned about. And so, in that, I think there's a certain consensus, and Helene and the records that it is shattering will contribute, I believe, to a hardening of that consensus that we live in a new era.

The Gulf Coast of Florida has been pummeled multiple times by disasters like Hurricane Helene, which can make some homeowners rethink where they want to live. (Photo: Florida Fish and Wildlife, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, we don't really know in dollar terms what the economic impact of Helene will prove to be. Those measurements will be taken in the years ahead. But if the insurance risk is 150 billion, a lot of people lost their jobs, lost their livelihoods, are out of work, are seeing the ability to sell their homes really decline. To what extent is the climate emergency a threat to our entire economy do you think?

LUSTGARTEN: Well, it's a huge threat to our entire economy. The research alone has already predicted long before this storm that climate pressures will create a drag on the national economy, 1.2% of GDP annually per single degree, per one degree of Celsius of warming, is the estimate that's in published, peer reviewed papers. And those estimates increase dramatically for the most vulnerable parts of the country, so parts of the Gulf Coast Florida, the counties that are closest to hurricane risk, for example, they're projected to see economic drags of up to 60% of their local GDP. So, there's already kind of a baked in assumption that the effects of climate change are going to make it harder and harder to have a vibrant and thriving economy. And part of what we're seeing when we talk about the costs of a disaster like Helene is, well, part of it is, what does it cost to rebuild and to make those people that were directly affected whole? Part of it, though, is going to be, what does it cost the federal government? What does it cost the National Flood Insurance Program? What do we choose to invest in it, in terms of not only aid to help people recover, but then all of the infrastructure investments and the policy changes that come afterwards, which will also be very expensive to try to build back these communities and to try to make them more sustainable and stronger in the future. And then what happens if and when we see another disaster that overlaps on this one, which is increasingly likely with climate change, so that basically, the costs of this one are not fully repaid before we have to start to pay the similar costs of the next one? And that's the kind of snowballing effect that can start to seem really scary to the economists that I talk to.

Our guest, Abrahm Lustgarten, imagines there may be a point in the future where basic emergency services could be hard to come by in particularly vulnerable locations. (Photo: Florida Fish and Wildlife, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: And what about the social and emotional costs here? Abram, I know you're not a psychologist, you're not a social psychologist, but you talk to many people in preparing your book about the uprooting of America. What do you hear are the social and emotional costs of disasters like this?

LUSTGARTEN: Well, first of all, I mean, my heart goes out to people who are impacted by this storm. The kind of destruction that I think we've all been looking at in newsreels is absolutely heartbreaking. And in my experience, talking to people who are affected in that way, I mean, obviously every person is different, and there's a spectrum of reactions. And some people will be immediately dislodged from their lives by an experience like this, and they will, might move, or they might make dramatic changes. Many other people will be resilient to a degree, and this is probably much more common. And you know, in the course of my reporting on migration, it takes many, many small impacts or incidents like this to add up to a decision to move or to migrate, and so if you look at a storm like Helene in that context, then I would think we have a gradation of its psychological impacts on people. That there are people who are on the Gulf Coast, who are in parts of Florida for whom this is the fifth disaster or the 10th disaster that they lived through. Some of them I've seen interviewed had just finished putting up the sheetrock on the repairs from what happened last year. And those people are very vulnerable and closer on the spectrum to giving in to that relentless drumbeat of bad news and risk, then maybe somebody in Asheville, North Carolina, for whom this storm was a surprise, for whom maybe they hadn't experienced an event like this before, so I'm sure that it shakes everybody you know, really to their core. But on the spectrum of what makes somebody actually move, there's really a gradation, depending on how many times this has happened to you.

CURWOOD: Abrahm, we have storms now that are traveling much farther inland than we expected. They're wetter, slower, more destructive. Some respects, it feels overwhelming. From your perspective and what people have told you, what’s to be done?

LUSTGARTEN: Well, I think that we are in an era where we have to anticipate the unexpected and we have to understand the limits of what we can know, and if you want to translate that uncertainty to hard plans, those plans might look like living and developing a community around a worst-case scenario instead of a fingers crossed scenario. And I don't know the community of Asheville very well, but I imagine that that might mean developing beyond the furthest reaches of the floodplain for worst case scenario, for example, or imagining that every storm could potentially have the kind of unexpected impacts that we saw in this storm. And that's really a reversal from how we've lived in the past, where we trust the data of history to inform the data of the future. And what it means to be in an era of discontinuity is that you can't trust that data anymore, and so you have to guess about how bad it could be. And if we can wrap our minds around a guess, a planning, a physical planning, you know, paradigm that imagines the worst case, then we can keep ourselves kind of beyond the boundaries of that worst case at least a little bit more reliably.

A Florida Fish and Wildlife Service member conducts a wellness check after Hurricane Helene. (Photo: Florida Fish and Wildlife, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Of course, preparing for that worst case costs a lot of money that people think that is a waste of money.

LUSTGARTEN: So, I talk about this a lot, and it's one of the more depressing elements of the climate adaptation story, I think, for the United States, and that's that the costs of adapting to climate change are going to prove so unfathomably expensive that I don't think that we collectively, or that our governments, can really wrap their minds around that yet. And the flip side of what that investment will require is what I believe is the reality, the truth that certain places will never be able to afford that adaptation, and this may be a very long ways into the future, and it depends on the frequency of disasters, but there will become places that are unprotectable, where we cannot afford to rebuild, where we cannot afford to build in the way that is truly resilient, because it is too expensive. And we're more likely as a society, to spend that money and make those investments in the larger urban places where there's a collectivization of the services and community support for the population that lives there. And so I think that, and we're trending into, like science fiction, you know, realm here, or at least my imagining of the future, but when I try to imagine what a community that is failing on the far end of this transition looks like the researchers that I talk to tell me to expect the disappearance of publicly provided services like garbage pickup, like 911 service and emergency services, and like the availability of insurance and those sort of basic community fundamentals first, and that might follow the decrease of a tax base that dwindles as the population shrinks, which also precipitates a drop in the quality of schools and a drop in the quality of infrastructure. So, all of these things start to sort of self-perpetuate and spiral downwards, and then once you lose that consistency of services and economic stability, I think of it as communities kind of de-evolving back into, I guess, what we would call a rural state, where eventually you have people who have to be self-sufficient and self-dependent in order to live there.

CURWOOD: So, Abrahm, what are the odds that Helene might just prove to be a tipping point for awareness of the growing risk from climate disruption in this country, and that there'll be broader acceptance in, in taking steps to both reduce our emissions and also to adapt to the effects of the emissions that have already been made.

Abrahm Lustgarten is a senior environmental reporter with ProPublica. (Photo: ProPublica)

LUSTGARTEN: I think there's a good chance that Helene alters the conversation. It depends in part on how that conversation is framed in the coming days and in the coming weeks, and whether we discuss what's happened in the context of climate change, and whether the attribution science comes out and says that Helene was significantly influenced by climate change. I mean, all of those things will steer this conversation, but I think that there's no doubt that the frustration and danger and horror experienced by so many people, particularly on the Gulf Coast, is reaching a saturation point of sorts that I would expect to change the conversation around climate change. And there's no doubt that in places like Asheville, North Carolina, that the level of surprise, of sort of dumbfoundedness that something like this could happen in this way from a hurricane that came off the coast and that it could dump so much water so quickly. I think that's a different kind of but similar kind of awakening. And absolutely, there will be fresh conversations in those parts of the country about whether this was climate caused, and what that means, if you're trying to imagine this happening repeatedly, what that means for your life and your future, and those are the seeds, then, for what will translate, one would hope, to offering political support for climate action, or supporting changes in lifestyle and behavior and consumption that lead to lowering emissions and so forth. And I think that's really what we're talking about when we talk about, do people see this as a turning point in their acknowledgement of climate change? Are they willing to do something about it?

CURWOOD: Abrahm Lustgarten is a journalist. His latest book is called “On the Move: The Overheating Earth and the Uprooting of America”. Thanks so much for taking the time with us again.

LUSTGARTEN: Thanks for having me on.

Related links:

- USA.gov | “Hurricane Helene”

- Get your copy of “On the Move: The Overheating Earth and the Uprooting of America" (Affiliate link supports both Living on Earth and local booksellers)

- Read more about Abrahm

[MUSIC: Bela Fleck with Sierra Hull, Molly Tuttle, Billy Strings, Michael Cleveland, “My Bluegrass Heart” on My Bluegrass Heart and on Youtube, Renew Records / BMG]

DOERING: Coming up, Green Party candidate Jill Stein says neither her Republican or Democratic opponents are taking the climate crisis seriously enough. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Barbara Higbie, “Tango Aurelio” on Murmuration, by Barbara Higbie, Slow Baby Music BMI]

Birdnote®: Here Come the Merlins

The Merlin may be small, but it packs a serious punch. In Medieval times, nobility used the bird to hunt sky larks. (Photo: Greg Thompson)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

DOERING: They are tiny birds, but tough ones. And they are flying against the trend of wildlife moving toward the poles as the planet warms, as Mary McCann tells us in today’s BirdNote®.

[BirdNote®]

Here Come the Merlins.

[Merlin calling, https://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/197047, 0.19-.22]

MCCANN: Want to see one of the blazing thunderbolts of the bird world? Smaller than a pigeon — but fierce enough to knock one from the air — are the powerful, compact falcons known as Merlins. While global climate change is pushing ranges of many birds farther north, Merlins are actually expanding southward.

Merlins nest in northern forests around the world. But in recent years, more and more Merlins have been nesting farther south, in towns and cities across the northern United States. These small falcons will take over old crow nests, especially in conifer trees — in parks, cemeteries, and neighborhoods.

[Merlin calling, https://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/197047, 0.19-.22]

No one knows precisely why, but part of the answer may lie in a rebound of Merlin populations since the banning of pesticides like DDT. And it’s a reminder that bird behavior may be more flexible than we sometimes imagine.

[Merlin call, https://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/105837, 0.15-.17]

Merlins reach their peak southward migration in October. Although some, like those in the Pacific Northwest, remain year-round, most scatter to the south for winter. Some travel as far as Ecuador. With any luck, you might see these adaptable, pint-sized thunderbolts in your neighborhood.

[Merlin call, https://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/105837, 0.15-.17]

###

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Recorded by Bob McGuire and Geoffrey A Keller.

BirdNote’s theme music was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

Producer: John Kessler

Managing Producer: Jason Saul

Associate Producer: Ellen Blackstone

© 2017 Tune In to Nature.org October 2017 Narrator: Mary McCann

DOERING: For pictures, soar on over to the Living on Earth website, loe dot org.

Related links:

- The “Here Come the Merlins” story on the BirdNote® website

- About the Merlin from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology

[MUSIC: Michael Hedges, “The Double Planet” on Live on the Double Planet, by Michael Hedges, Windham Hill Records]

Jill Stein for the Greens

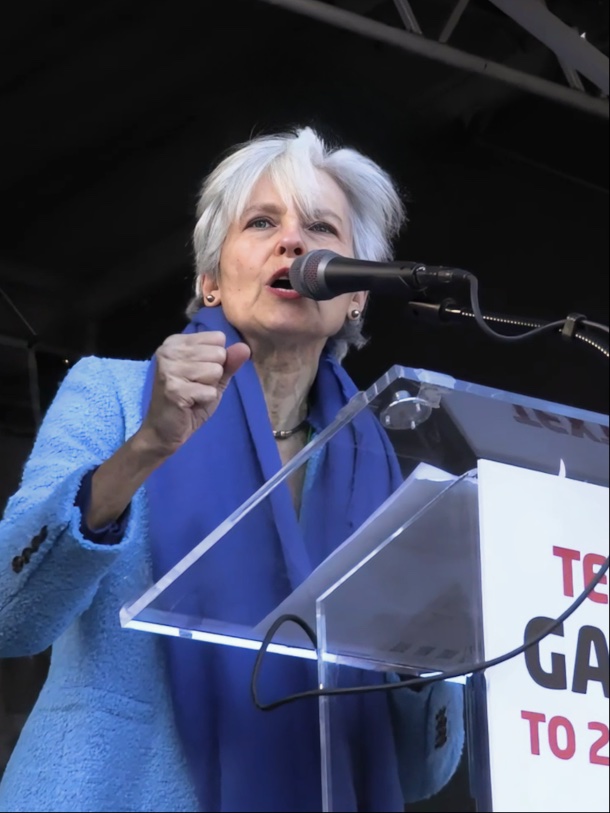

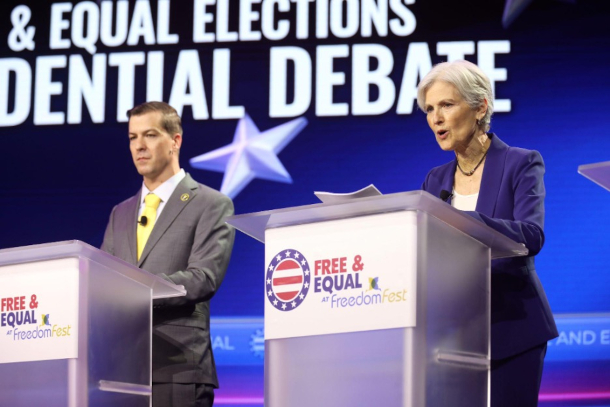

Green Party presidential nominee Jill Stein speaking with attendees at the Free & Equal Elections Presidential Debate at the 2024 FreedomFest at Caesars Forum Conference Center in Las Vegas, Nevada. (Gage Skidmore, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: As we get closer to election day, we are covering the environmental platforms and claims of the presidential candidates. During past weeks we have explored the records and promises of both Democrat Kamala Harris and Republican Donald Trump. This week we’re joined by Dr. Jill Stein of the Green Party. This is not her first presidential race. Jill Stein also ran as the Green Party candidate in 2012 and 2016, getting nearly a million and a half votes in 2016. Although she’s running far behind the two major party candidates in the polls, she could pull thousands of votes in swing states and potentially impact the outcome of the election. Dr. Jill Stein joins me now. Welcome back to Living on Earth!

STEIN: It's great to be with you, Jenni. Thanks so much for having me.

DOERING: So, what are the major environmental issues that the United States needs to address, in your view?

STEIN: I'd say everything, you know, it's like, which is the greatest emergency? I think the climate crisis, it's a unifying issue because it connects to the crisis of temperature and storms and floods and drought and our water supply and our food supply, you know, the survival of our oceans and our forests. So, it's a very unifying issue that kind of brings all ecosystems into focus. Yes, of course, there are many issues that converge here. It's not just the climate, and we put them all together in a green New Deal, which addresses the issues in our economy at the same time that it's addressing many environmental issues that bear on the climate. So, a green new deal would not only change our energy system to clean renewable energy, put conservation and efficiency to work and all that in our homes and our electricity and all energy uses. But then we also look at transportation and the need to move to public transportation system so that we can actually get people where they need to go in a way that is sustainable and workable for a quality of life in our communities. We look at housing also as a critical issue, because housing is a major use of energy, and we also have a housing crisis so why not solve them both at once. And on agriculture we need sustainable systems of agriculture that can endure the very trying conditions of the climate crisis, but which also don't contribute to the climate crisis the way that our current agricultural system does. So, all of those are kind of key needs. If we're going to solve the climate crisis, we also have to solve these other issues.

Jill Stein is the 2024 presidential candidate for the Green Party. (Photo courtesy of the Green Party)

DOERING: Now this is not the same as the Green New Deal that many people have heard about. You call yours a "Real Green New Deal". What's different?

STEIN: So, the other one that people have heard about is a knockoff from this. So, this was launched in 2010 in New York by Howie Hawkins, running for governor at the time, and it was adopted by many other green campaigns in this country but before that, it originated in Europe with the European greens, and it really calls for a emergency phase out of fossil fuels. The Green New Deal put forward by AOC and Senator Markey doesn't phase out fossil fuels, it just increases the supply of renewable energy, which is good, that's like a first step, but the climate actually doesn't care about renewable energy. The Climate cares about fossil fuels and CO2 production and greenhouse gas production. So, it's not really a Green New Deal, unless it is phasing out on an urgent basis the production of fossil fuel energy.

DOERING: Now the Green New Deal, it never did actually become law, but the inflation Reduction Act of 2022 has been acknowledged as a big step forward and a major climate accomplishment for the Biden administration. I understand that you disagree. What do you think was missing from it?

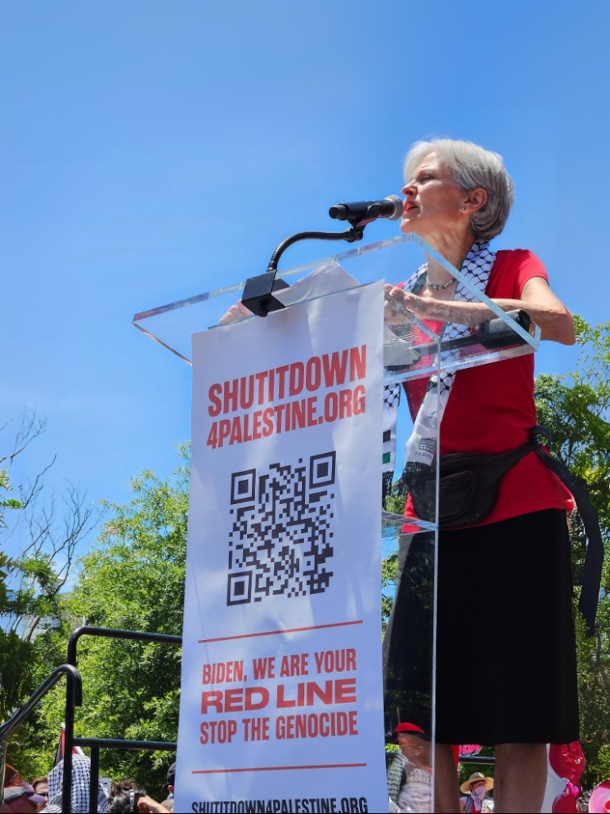

The Green Party calls for a “real green new deal” as well as a permanent bilateral ceasefire in Gaza and Lebanon and a full arms embargo on Israel. (Photo courtesy of the Green Party)

STEIN: The Inflation Reduction Act actually increases; it mandates much greater production of fossil fuels. So, it's going in the wrong direction. It does some good things, it creates some green jobs at the community level, especially but the net balance is drastically in the wrong direction. You may recall that Joe Biden ran for office saying that there would be no sales of public lands for fossil fuel extraction. Well, the inflation Reduction Act, unbeknownst to most people, it requires that millions upon millions of acres of offshore water be auctioned off before any major renewable projects can be built. And the same is true for onshore there need to be 2 million acres auctioned off every year. So, it essentially mandates huge increases in fossil fuel production before any major progress can be made on renewables. So, in my view, that's definitely a huge strike against the Inflation Reduction Act. And it also has money for nuclear energy, which is problematic in the view of Greens, and I think objectively. If you get outside of the hype and the spin, nuclear energy is not going to solve our energy problems and is actually not cost competitive with renewable energy and has no solution for the problem of toxic nuclear waste. So, on many counts this is not the direction that we need to go in.

DOERING: Well, I mean, I imagine that the people involved in passing it and President Biden himself might argue that, you know, we had to make some compromises. You know, overall, does a wonderful job. It's not perfect, but we had to work with Senator Joe Manchin to get his vote. How would you respond to claims like that?

STEIN: I think you can't throw the baby out with bath water. You know, it's like if your compromise is destroying the climate and it's understood that if we're going to fix a climate crisis and prevent it from crossing tipping points that we get closer to by the hour, if we're actually gonna make progress, we have to reduce fossil fuel output. You know, so even the goals that were adopted by the Biden administration, we don't get closer to those goals by selling off millions upon millions of acres for extraction. It's exactly the wrong thing and unfortunately, the powers that be on Capitol Hill are forever finding ways to justify pleasing their big donors and that's the issue here. You know, it's not unique to energy but this is just the way the American system works, which is why we're not solving our problems, whether it's health care or student debt, or the expanding war machine, the housing crisis, we're not solving these problems because at the end of the day it's the industries which are being served by the politicians who are taking their money.

Libertarian Party presidential nominee Chase Oliver and Green Party presidential nominee Jill Stein speaking during the Free & Equal Elections Presidential Debate at the 2024 FreedomFest at Caesars Forum Conference Center in Las Vegas, Nevada. (Photo: by Gage Skidmore, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: Dr. Stein the Green Party has aligned itself with the antiwar movement. How would you characterize the intersection between environment, war, international relations?

STEIN: That's a great question and it's a huge connection. So, for one thing, war blows things up, right? That's just kind of the nature of war, whether it's on the battlefield or in the upper atmosphere or in the oceans, it's blowing things up. So right there, it's destroying the environment, just on a most basic physical level. It's emitting huge quantities of CO2. So, that's another way that cutting back on the military actually saves the climate as well and then there's the whole issue of military pollution. You know, the PFAs epidemic that we're dealing with right now, where every one of us has detectable levels of PFAs in our bodies, and we don't know what the safe level is. If there even is any safe level whatsoever. It's military bases and military operations that are using this PFAs foam. So, the ways that the military destroys our environment is really worth looking at and it again, provides another reason why we don't want to shoot first and we don't want to be, how did Kamala Harris put it, the world's most lethal fighting force. That's not something to pride ourselves on. We want to be the world's greatest humanitarian force, and we want to be working on principles of international law and human rights and diplomacy to avoid war and conflict and to avoid the preparation for war, which both makes war inevitable and also is very polluting and destructive in and of itself.

DOERING: Now during the 2016 presidential election, Green party votes in a few swing states were actually larger than the margin that Donald Trump won those states by. For example, in Michigan, you received over 51,000 votes. Trump defeated Clinton by just shy of 11,000 you also drew more votes in Wisconsin than the margin between the two major party candidates. So, some people say that your votes tipped the election to Trump. And then, of course, when he came into office, he rolled back environmental regulations and took the US out of the Paris Agreement. How do you respond to those who say that voting for you in a swing state could result in a similar outcome in 2024?

Dr. Jill Stein alongside the Green Party vice presidential candidate Butch Ware, a historian and UC Santa Barbara professor. (Photo courtesy of the Green Party)

STEIN: So let me say it's a very flawed analysis, and I can tell you why, you know, it's a concocted mathematical model which doesn't work because, and let me speak to that point first, and then we can address the other issues. But first of all, the biggest factor out there in the voting population is those who don't vote. In 2020 it was one out of every three eligible voters. It was even higher in 2016 when I was running. So, there are huge numbers who've already voted with their feet, and they say, we reject this system. We know that people who voted green were largely coming from the non-voting pool. So, what third parties largely do is give people a reason to come back in and vote. So, it's absolutely false. It is a really manipulative you know, there's a saying there's lies, damn lies and statistics. These are some of those damn lies through statistics that make people think that your vote was taken away from someone else. For the most part that's not true but let me just back up from that to also say that's what elections are about. Elections are about winning votes and anyone who tells you that your votes belonged to someone because you happen to vote for that party before, you know that's completely false. That is an anti-democratic notion because our lives are changing, the issues are changing. And the question is, what has that politician done for you and what are they offering? And do you believe them? You know, these are the questions here. This problem of potential vote splitting, that maybe there is a progressive group of voters, and they could be diverted among candidates. That is a problem that has long been solved. It's called ranked choice voting, which Greens have been promoting ever since we've been in the political process. We've always been saying "would you please just pass ranked choice voting?". And it's been passed in something like 27 municipalities, t's a great system. The Democrats, in fact, adopt it, but only for their primaries, because it avoids any potential for vote splitting and it ensures that no one is ever going to get elected without a majority and it ensures that you're never throwing away your vote on a candidate who doesn't have the momentum to actually make it into office. Because the way it works is that your choices are ranked. That's why it's called ranked choice voting. So, you could say, oh, I want to vote for this underdog, Ralph Nader say, you know, and Al Gore would be my second choice. That way, if Nader didn't win that election, your vote would be automatically assigned to Gore if there wasn't a winner prior to a runoff. If somebody already has a majority, then you don't need the runoff, and the vote having been split doesn't matter, because somebody has a majority, and what's left outside of the majority wouldn't win the election anyhow. So, it kicks in when it's needed, and it ensures that the vote will never be split, and it ensures that you can go ahead and vote your values, because right now, people are generally voting against who they hate the most instead of voting for what we want. And that's no way to run a democracy. A democracy needs a moral compass. It needs a vision. It needs the idea that we could have a climate that we could live in and green jobs that ensure no worker will be left behind.

DOERING: Dr. Jill Stein is the presidential nominee for the Green Party. Thank you so much.

STEIN: Thank you so much Jenni, good to talk.

Related links:

- Listen to our conversation with Jill Stein in 2016

- Learn more about the Green Party

- Learn more about Howie Hawkins and the Green New Deal

- POLITICO | “Green New Deal won’t call for end to fossil fuels”

- Sierra | “The Dark Side of the Inflation Reduction Act”

- Learn more about the 2016 Wisconsin presidential election results.

- Learn more about the 2016 Michigan presidential election results.

[MUSIC: Stan Samole, “Inch Worm” on Childish Dreams, by Frank Loesser/arr.Stan Samole and David Antonacci, JAZZ INSPIRATION Records]

CURWOOD: The outcome of the 2024 US presidential election could profoundly shape the future of the climate and environment both at home and around the globe. And there are important down-ballot races and ballot measures too. What issues are you most interested in having us cover? Let us know by sending us a written or audio message at comments@loe.org. You can use the Voice Memos app on the iPhone, the Voice Recorder app on an Android device, or any similar app to record your message and then email it. And we might just include your voice on the air! So, email us, at comments@loe.org! And please include a daytime phone number where we can reach you to verify your submission.

[MUSIC: Stan Samole, “Inch Worm” on Childish Dreams, by Frank Loesser/arr.Stan Samole and David Antonacci, JAZZ INSPIRATION Records]

DOERING: After the break, a Sudanese climate activist describes the human tragedy unfolding in her country amid war, floods, and famine. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Joel Mabus, “Grand Old Rag” on Parlor Guitar, by George M. Cohan/arr.Joel Mabus, Fossil Records]

Sudan's Climate and War Misery

In the aftermath of the collapse of the 30-year Bashir dictatorship in 2019, Sudan has been devastated by the impacts of climate change and the ravages of war as two rival generals struggle for power. Millions of Sudanese have fled their homes. Pictured above are displaced communities in Zam Zam camp for Internally Displaced People (IDP) in North Darfur. (Photo: Albert Gonzalez Farran, UNAMID, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Sudan in Northeastern Africa is one of the world’s most climate-vulnerable nations, often grappling with deadly rainfall and flooding, as well as devastating droughts. It has also been torn by war, off and on, for decades. Since 2023 when two rival generals launched the most recent armed struggle for power, according to the UN Refugee agency more than 7 million Sudanese out of a population of 50 million have fled their homes. These internally displaced persons or IDPs, inhabit camps where many bake in heat waves of 128-degrees Fahrenheit and fall prey to disease, violence, and starvation. And another 2 million or so Sudanese have fled over the borders to Ethiopia, Chad and South Sudan, where conditions can be just as bad. Trained as a physicist, Nisreen Elsaim is a young climate activist and was co-chair of the UN Secretary General’s first youth advisory group on climate change. In the summer 2023 as fighting escalated, she was forced to flee Sudan along with her then nine-month-old son. She is presently based in Berlin, Germany. During the opening of the general assembly of the United Nations and Climate Week in New York City last month, Nisreen spoke with me about her call for humanitarian aid for Sudan and the region. Please be aware our discussion contains events and conditions you may find alarming, including mention of sexual violence.

CURWOOD: Nisreen, tell me what are some of the ways the climate crisis has worsened the situation for everyday Sudanese?

ELSAIM: In General, or after the war?

CURWOOD: Take your pick.

ELSAIM: Okay, so let's start from what's very recent, and then go back. So, Sudan is a big country, as you may know, and we have 18 states; 14 states are experiencing ongoing clashes, and people had to flee to either neighboring countries or other states within Sudan. So out of 18 states, only four states doesn't have ongoing clashes and like air shelling and gun firing and stuff like this. So, a lot of Sudanese took them as shelter. Unfortunately, they were the states that are heavily impacted by the worst floods we had in a century. And basically, these four states are as big as Germany in size, and they are all under the water, as we speak. And it's very, very devastating, because 27 villages disappeared, like melted, like salt or sugar in water melts, because the area is a very dry, very desert area, actually. So, most of the house materials they build the houses with is mud and sand. So, when the water come, it was just like putting a cotton candy in a water. This is exactly how we are, really, so, and this, of course, results 1 million more to add to the crisis of 12 million IDPs and refugees already because of the war and ongoing clashes. But I think the most devastating is that a lot of the IDP camps were actually flooded, so people had to flee for the second time, sometimes for the third time, losing everything all over again. Moving to a new place all over again, and this made a lot of people extremely vulnerable and extremely traumatized, I think the last but not least, the burden that comes with floods, waterborne diseases. And of course, the health system is collapsing because of the war. Already, 80% of the hospitals in Sudan are out of the service because of the shelling and because of the fighting, so now the government declared cholera. Unfortunately, we have more than 500 cases who passed away due to cholera. And in Kassala, which is in the eastern region of Sudan, one of the isolation camps for people who have cholera, was actually flooded.

“Who told you we have the privilege of losing hope?

— UN OCHA Sudan (@UNOCHA_Sudan) October 1, 2024

The numbers you read is not just numbers, they are actual people … they are actually me” @NisreenElsaim the peace and climate activist urges the global community to #KeepEyesOnSudan pic.twitter.com/Ed08FyWHnZ

CURWOOD: So just since 2021 and then the long history that you alluded to, how has the situation related to the climate emergency worsened over the last decade or so?

ELSAIM: So basically, we used to have floods every 20 to 15 years, minimum, and people used to be named after the floods because it was really rare. So, they say X was born in the year of flood. Now, I think we experienced the very bad floods in 2013 another very bad floods in 2018 and another catastrophic floods in 2020 and now in 2024, so it's more current. And instead of having a lifespan of 20 or 25 years between floods, now we have it every three or four years maximum. This is one side. the second side. Of course, the issue of climate change, peace and security and how can climate change trigger conflicts in Sudan is not new. I mean, the first time there was a systematic integration of the two issues was with the war in Darfur, when the previous Secretary General, Ban Ki-Moon said that the war in Darfur is actually the first war in the new history that is climate driven. And then, of course, we know that the war in Darfur did never actually finish, and they are the root cause of a lot of what's happening right now in Sudan. So yeah, and if you really dig deep to the root causes of that war, it's basically conflict between farmers and pastors over Russia sources, because nothing is enough for the people anymore. And Sudan, of course, is not the only country. Most of the Sahel and Lake Chad and the Congo Baisin. A lot of communities in these places are witnessing are very rapid losses of resources, and it's making their lives really, really harder. Of course, now in Sudan, having a temperature of 52 to 53 Celsius in the summer is very normal, to the point that people even don't stop, they just continue their life normally.

CURWOOD: How do you deal with a temperature like that?

ELSAIM: I think we have a dragon grandfather, really. Because for me, even when I see people in the street walking and using public transportation, cooking and drinking tea in the side of the street. I was like, I don't know. I really think maybe we have a dragon grandfather.

Children have not been spared the harsh realities of war and the impacts of climate change. Nisreen Elsaim visited with young refugees during her visit to the region earlier in 2024. (Photo: courtesy of Nisreen Elsaim)

CURWOOD: Global leaders came to New York to talk about climate change. What does the outside world need to know about the humanitarian and climate crisis that the Sudanese people are facing right now?

ELSAIM: Well, to be honest with you, I think there is a fatigue, international fatigue, in terms of doing something about the current problems. I think people are overwhelmed, and not only people. I'm talking about governments; I'm talking about private sector. I mean, the whole international community is overwhelmed with what's happening on Ukraine and what happened before in Libya and Yemen and Syria. And there is a lot of conflict coming over and over, very quickly after each other. And I mean, we are witnessing the worst era since the World War Two, when it comes to how many conflicts we have around the world, and of course, the catastrophic genocides in Gaza and so on. But then, does humanity have priorities? Or all humans are equal? I mean, this is the question that we need to keep asking ourselves.

CURWOOD: So, you mentioned the catastrophic genocide in Gaza and a certain extent now the West Bank, even, about 40,000 people have estimated to have died there. What's been the death toll in Sudan?

ELSAIM: 52.

CURWOOD: So, more people dying in Sudan?

ELSAIM: Definitely. We have bigger population. We have bigger land. I think the only thing that makes the situation in Sudan 1% maybe better than the situation in Gaza is we had borders to escape to, while people in Gaza did not have it. But in terms of the number of IDPs and refugees, 12 million until now, which is the biggest internationally, stage five famine, the number of victims is bigger. The intensity of violence is also somehow bigger. And also, there is something that is very against the human rights and a huge violation of humanity, is that in Sudan, there is a tradition of systematic rapes. So, they actually use rape as a weapon in the wars, not like only bullets and killing. And this leaves, like a whole generation of young females totally devastated, not only them, but their families, and they don't have a future. And, yeah, I think, I think, as a woman, I prefer to be killed than to be raped.

CURWOOD: When was the last time you were in Sudan?

ELSAIM: I did another trip back to Sudan in January this year, January 2024 I went to port Sudan because Khartoum is definitely no go and there's no airport there anymore. So, I went back to Port Sudan. I used the ship. It took me 34 hours to reach from Jeddah to Port Sudan, and then from Port Sudan to Jeddah back to Saudi Arabia, and I visited a lot of camps, of the IDPs camps there, and the situation was just more than anyone can take. And there is no actual camps. So, they are located inside of schools. They put one school for women and girls and one school for boys and men. And of course, there's a lot of violations happening there, but also a lot of unrest, because it's a school; it's not, it's not even a camp. Even a camp would be better than, than that situation. I also visited some camps of refugees outside Sudan. So, I visited the camp in Uganda, and I visited the camp in Chad and Ethiopia, and it's even worse than you can imagine. They are in a new country that speak a different language, a different nature, and thousands of people have only one toilet, and it's very far to the point that if you're going to the toilet, the whole camp will know that you're going to the toilet. So, a lot of girls didn't go to the toilet because they just didn't want everyone to know them. There is a culture in that, and a lot of urine infections and a lot of kidney diseases start to show because they are just simply holding their pee without going to the toilet. But if you risk you going to the toilet at night when no one is looking, then you get raped, because there's no lights in the way to the toilet, and there's no security, so anyone can do anything without really someone even knew who that person was. So, there was a lot of rape cases in the in the camps, in a lot of places.

CURWOOD: Somebody listening to this now is horrified and at the same time wondering, how does this link back to the climate emergency that we're in now, how does that aggravate add to make these horrible things more possible? Because the climate is being disrupted.

ELSAIM: Definitely. One of the biggest solutions to climate change is renewable energy, and it's also one of the biggest solutions for the suffering of a lot of people. A lot of people have malnutrition, not because they don't have something to eat, but basically because they don't have something to cook with. So, we're trying to introduce solar cookers for these people. Lighting, which is a huge problem, as I told you, there's no lights through the road to the toilet. Solar of young girls get raped, and solar torches and solar lights is very much doable. The idea with solar energy, and why it works very much in such contexts, is that is, it's so decentralized, so it doesn't have to have a government or a grid or anything anywhere can use it. And there's a lot of sun, I told you, we reach 54 degrees sometimes celsius in summer, so there is a lot of solar radiation. So, I think the suffering of Sudanese people currently is from both from climate change, but from the conflict. But the answers that fix the climate change problem could actually also fix the conflict and the war problems, not all of them, but at least make the life of these people at least 1% better.

During her conversation with LOE’s Steve Curwood, Elsaim spoke about visiting IDP and refugee camps to learn of the plight of those forced from their homes. The war has taken a considerable toll on women, who face the constant threat of violence. Listeners should be aware their discussion contains events and conditions they may find alarming, including mention of sexual violence. Photo: Nisreen Elsaim visits with female Sudanese refugees in camps. (Photo: courtesy of Nisreen Elsaim)

CURWOOD: Your focus is on youth as key actors for climate adaptation. Talk to me about the role that the youth of Sudan and elsewhere in Africa and around the world can play to help alleviate the impacts of climate disruption.

ELSAIM: I think the first and the biggest role that young people are trying to do right now is the, to raise the awareness of the problem itself, to make their communities aware that something like this is happening, and maybe help them to adapt, because climate change is a problem. But if you don't know that the problem exists, then how can you even think of a solution for it? Right? So, I think this is the first, maybe obvious role of young people, but the one that I think a lot of people don't talk about or neglect is that the young people are the first respondents when a climate crisis happen. They are the ones who rebuild their communities. They are the ones who are easily communicating and easily organizing and easily reaching others to really help them. And in Sudan, is not different, is it? We have something called the emergency response rooms, and it is a very local youth led processes to aid the communities and the neighborhoods, even without support, without financial support, without UN support, without Red Cross, without any support. And it was the same in the times of the floods all over the different floods I attended, like 2013, 2018, 2020, yeah, they had something called nafir and it was a basic… Nafir in the Sudanese context means collective action. This is the local word of collective action, nafir. And Nafir was a very famous program where volunteers from all over Sudan did amazing work. People sometimes volunteer their cars if they don't have time, like 4 by 4 cars where they can go into the mud and the water just to deliver things. Some people were volunteering, even their Tuk Tuks, and they were used as ambulances because we needed something small and can also fit the small streets to take the people who are injured. Some people were denoting money. Some people were on the ground themselves. And it is not different. A lot of African countries having the same the people in the Sahel region, especially in Burkina Faso and Chad and in Mali, are doing the same with their communities, planting trees to reduce the impacts of the desertification, trying to communicate about plastic pollution in Ghana and in Senegal and all of the coastal cities and coastal countries, planting even more trees in Kenya, fighting biodiversity losses in Tanzania, I can go more and more. The energy, the aspiration, the drive for change that young people have, not only for climate change, but for all of sorts of issues, is always marvelous.

CURWOOD: Indeed. Nisreen, you're passionate about your demands for global action on climate disruption. So, what do you see as the signs of hope or optimism in your campaign?

Nisreen Elsaim in New York City during Climate Week. Trained as a physicist, Elsaim is a young climate activist and was co-chair of the UN Secretary General’s first youth advisory group on climate change. In summer 2023 as fighting escalated, she was forced to flee Sudan along with her then nine-month-old son. She is now presently based in Berlin, Germany. Elsaim spoke at the recent United Nations meeting on Sudan: Inaction is Not an Option. (Credit: Living on Earth)

ELSAIM: Well, if I have to be honest, I don't see any signs for hope, but I am also in a position where I don't have the privilege of losing hope. So, for me, hope is not about the science that others shows for change, but about my inner drive and about the issue being still there. And I'm not a pessimistic, but when I say there is no science, I'm talking about the current situation and the very obvious behaviors by world leaders, for example. We are heading into 3.4 Celsius in terms of global warming. But remember, the Paris Agreement goal was 1.5 degrees, 2 degrees Celsius in the worst-case scenario. And even with 1.5 Africa will lose at least 30 of its resources, natural resources, and with the two degrees, we lose more than 80% of our resources. So now we're going to 3.4 and this is something not even like imaginable, at least from my side of view. They are talking now about loss and damage, but losses and damages are all too late, right? They are talking about adaptation to climate change. It is very important, but you can only adapt until a certain point. What if the world is not adaptable anymore? What if we reach the break point where the environmental system doesn't work for us as humans anymore? Mitigation and a serious phase out of fossil fuel is a must. All of the work around that, without a serious cut in the emissions, is going to go with the wind, if not today, next day, the year, if not next year, the year after, if not this decade, the decade after. And I think we are all have to face this reality.

CURWOOD: What gets you out of bed in the morning? How can you get out of bed, knowing how things are as difficult as, as we've talked about today, people literally dying in your homeland for lack of food, water, it's too hot, there's disease, there's war raging. How do you get up in the morning and stay at it again?

ELSAIM: I can still do something about it, even if it's small, even if it's saving the life of one people, even if it's helping one student to get a scholarship. I can still do something about it, and as long as I can do something about it, I cannot stop. Everyone can do something about it. They just need to know that they can do something about it and take that action.

CURWOOD: Nisreen Elsaim is currently a fellow at the Robert Bosch Academy, working on climate change, peace and security for her homeland in Sudan. Thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

ELSAIM: Thank you. It was a pleasure.

Related links:

- Learn more about the humanitarian crisis in Sudan

- The Guardian | “How water is helping to end 'the first climate change war”

- Sada Middle East Analyst | “Climate Change and Conflict: A Perfect Storm in Sudan's Countryside”

- Learn more about Nisreen Elsaim

- Watch a UN meeting titled The Cost of Inaction: Urgent and Collective Support to Scale Up the Humanitarian Response in Sudan and the Region

- BBC | “'Rape me, not my daughter' - women tell BBC of sexual violence in Sudan's civil war”

- Human Rights Watch | “Sudan: Widespread Sexual Violence in the Capital”

[MUSIC: Amira Kheir, “Ahel Allel” on View From Somewhere, Contro Cultura Music]

DOERING: Next time on Living on Earth, people with physical disabilities can explore new terrain thanks to offroad wheelchairs.

SUGIHARA: And it just completely opened up my world. I think we all gain a lot from being outside in nature.

DOERING: How accessible trails, adaptive wheelchairs and nonprofits are helping people of diverse abilities enjoy the outdoors, next time on Living on Earth from PRX.

[MUSIC: Amira Kheir, “Ahel Allel” on View from Somewhere, Contro Cultura Music]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Kayla Bradley, Josh Croom, Daniela Faria, Swayam Gagneja, Sommer Heyman, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Nana Mohammed, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari.

DOERING: Special thanks to interns Shanzay Asif and Karen Elterman for all their hard work and good cheer. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Allison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and YouTube Music, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments at loe dot org. I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth