October 18, 2024

Air Date: October 18, 2024

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Climate and the PA Senate Race

/ Kiley BenseView the page for this story

As control of the US Senate hangs in the balance, the Pennsylvania race between Democratic incumbent Senator Bob Casey and his Republican challenger Dave McCormick is heating up. Inside Climate News reporter Kiley Bense joins Host Jenni Doering to explain the climate and environment dimensions of Pennsylvania’s Senate race. (09:46)

BirdNote®: A Bird in the Hand

/ Michael SteinView the page for this story

Pennsylvania is known for its unusual town names, which include Burnt Cabins, Intercourse, Pillow, Chinchilla, Hazard and Panic. In today’s BirdNote®, Michael Stein shares how one small community came to be called “Bird-in-Hand”, Pennsylvania. (01:58)

Environmental Racism Case Appealed

/ James BruggersView the page for this story

In the lower Mississippi River region commonly known as Cancer Alley, communities of color live among industrial pollution while white neighborhoods have been mostly spared from heavy industry. The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals is now considering whether to allow a landmark environmental racism lawsuit brought against the local government to go to trial. Inside Climate News reporter James Bruggers discusses the case background and context with Host Aynsley O’Neill. (11:08)

Eagle!

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

Rise early in the morning and head out to a nearby national wildlife refuge, and you’ve got a good shot of being rewarded with the sights and sounds of all kinds of birds. And on this birdwatching trip, you might be watched back, Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence Mark Seth Lender reports. (02:37)

Europa Clipper On Its Way

View the page for this story

The Europa Clipper spacecraft recently blasted off into space to start a six-year journey towards Jupiter’s icy moon, Europa. On a series of close flybys, Clipper is designed to gather data that could indicate whether Europa might harbor life in the enormous liquid water ocean it appears to have beneath its icy shell. (01:37)

Journey to a Melting Glacier in Antarctica

View the page for this story

Thwaites Glacier in Antarctica holds enough ice that its melting could raise sea levels worldwide by 2 feet, but it’s so remote that until recently no one had ever approached where it meets the sea. Elizabeth Rush was a writer-in-residence on board the first research icebreaker to visit Thwaites and chronicles the journey in her book The Quickening: Creation and Community at the Ends of the Earth. She joined Living on Earth Host Steve Curwood to share the experience of witnessing the glacier’s unraveling and the crucial data the scientists on board unearthed. (19:01)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOSTS: Aynsley O’Neill, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Kiley Bense, James Bruggers, Elizabeth Rush

REPORTERS: Mark Seth Lender, Michael Stein

[THEME]

O’NEILL: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

O’NEILL: I’m Aynsley O’Neill

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering. The battle for a key Senate race highlights the political power of fossil fuels.

BENSE: I do think that what happens in Pennsylvania is really important far beyond the borders of our state in part because it's such a microcosm for the country. And I think until we start to see real change in a state like Pennsylvania, we're not going to have real change at the national level either.

O’NEILL: Also, Cancer Alley residents seek a moratorium on industrial plants in Black neighborhoods.

BRUGGERS: This case has focused a lot of attention on long term impacts of decisions that were made decades ago, about certain land use practices that led to segregation and then the resulting environmental impacts that come when you have various kinds of development or chemical plants in those areas.

O’NEILL: That and more, this week on Living on Earth—stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out in The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Climate and the PA Senate Race

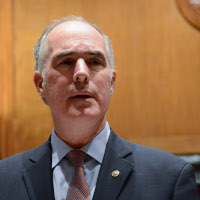

Pennsylvania’s Democratic Senator Bob Casey has served three terms so far and is up for reelection this fall. (Photo: AFGE, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

O’NEILL: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering. As control of the US Senate hangs in the balance, the race for a seat in Pennsylvania is heating up. Democratic incumbent Bob Casey faces Republican challenger Dave McCormick, and the race appears close enough to go either way. Here to explain the climate and environment dimensions of the Pennsylvania Senate race is Kiley Bense. She’s a Philadelphia-based reporter for our media partner, Inside Climate News. Welcome to Living on Earth, Kiley!

BENSE: Thank you so much for having me.

DOERING: So give us a sense please of who these two candidates are. Where do they stand on climate and the environment? Let's start with the incumbent, Democratic Senator Bob Casey.

BENSE: So Bob Casey is a three time incumbent. This would be his fourth term in office as a Senator, and he has become more climate conscious in recent years. He's a big supporter of the Inflation Reduction Act, which was passed under the Biden administration, and he's been really vocal about investing in clean energy technologies and using that as a way to combat climate change. Dave McCormick, who is the Republican challenger, he has a more complicated record on climate. So I think overall, he's trying to walk a kind of middle ground, a tightrope line, I guess. You know, in order to win Pennsylvania, because it's a purple state, he needs to win over moderate, middle of the road, swing voters. And so he is one of those few Republican candidates who acknowledges that climate change is real and that it's happening. If you read his energy policy platform, he says that we need to tackle climate adaptations. We need to think about ways to adapt to a changing climate. But then, on the other hand, he says a lot about how we need to do more fracking, how we need to roll back regulations, how we need to do, increase oil and gas production in the state.

DOERING: And so what's the record for Democratic Senator Bob Casey when it comes to fossil fuels and fracking in particular, which is huge in Pennsylvania?

Republican Dave McCormick is challenging Bob Casey in the race. (Photo: Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BENSE: So this has been a huge point of contention during this race in particular. Dave McCormick has really sought to tie Bob Casey to Vice President Kamala Harris's past comments about fracking, but the truth is that Bob Casey has always been supportive of fracking. He says, if you read his platform, he'll say that he's for what he calls responsible fracking. But that does not mean that he is against natural gas development at all.

DOERING: And how does he define responsible fracking?

BENSE: Basically, he's saying that we should keep fracking as long as it's done safely and it's regulated. And I think that if you were to ask environmentalists or people in Pennsylvania who really work on these issues on the ground, they would say that it is not being done safely and not being regulated enough.

DOERING: So to what extent has Bob Casey supported any legislation that would try to regulate and make fracking more responsible?

BENSE: So he did co sponsor a bill called the FRAC Act, which Dave McCormick has brought up a couple times as a way to attack Casey. You know, McCormick has said that Casey is against fracking, or he's in line with Harris, and that he would ban it. There's no evidence for that, but it is true that he did co sponsor this bill, which, among other things, would have made it a requirement for companies to disclose the chemicals they use when they're fracking. That bill never went anywhere. I don't believe it ever came to a vote.

DOERING: Now 18 years is a long time to be in office. To what extent have Senator Casey's views on climate change shifted over that period?

While fracking remains a buzzword in national politics, other issues like abortion and inflation are higher priorities for many Pennsylvania voters. (Photo: FracTracker Alliance, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BENSE: I think that he's always been relatively pro environment in terms of how he's voted, but in the last few years, he's become more vocal about his support for climate change measures. The League of Conservation Voters gives him a 94% score on his environmental record, and that's fairly consistent across his three terms. I think that he's maybe been talking about these issues more in the last few years. You have to keep in mind, because the oil and gas industry is quite powerful in Pennsylvania, for our statewide politicians, there's a lot of political calculus that happens when they talk about oil and gas and when they talk about climate change.

DOERING: How much do you think that climate change as an issue has been on Pennsylvania voters' minds in recent years?

BENSE: So I think unfortunately, for people who care a lot about this issue, in terms of how Pennsylvania voters rank climate change, it's pretty low. A lot of other issues come first, so things like jobs, inflation, reproductive rights and abortion, border security and immigration, these are all things that are coming before climate change and also before fracking and energy issues as well. I think for a lot of Pennsylvanians, that national conversation where fracking is such a buzzword and people equate winning Pennsylvania with having a certain position on fracking is really frustrating. If you look at polling on fracking, Pennsylvanians are very divided. There's no consensus. There's a lot of ambivalence. And this is one of the reasons that it's not the type of issue that if you go all in on fracking, you're going to win Pennsylvania, because especially in the parts of the state where there's not fracking happening, like here in Philadelphia in southeastern Pennsylvania, which is where a lot of the population lives, it's not something people are talking about, and especially when they're thinking about who they're going to choose to vote for, it's not an issue like, say, abortion that is going to sway you to one candidate or another.

DOERING: We've reported in this election season about how much young voters especially care about climate change. How does that factor into the Pennsylvania Senate race and you know, concerns about young voters turning out for these candidates?

BENSE: So as this race has become tighter and more competitive, it becomes more important for someone like Casey to appeal to parts of the Democratic constituency that maybe in the past, he could have taken for granted, or maybe weren't as important to his victory. And young voters in this election are a key part of that. Young voters in Pennsylvania, like in other parts of the United States, tend to care a lot more about climate change. They care more about figuring out what we're doing about things like fracking, and they are kind of looking at Casey's record and wondering what he might be like if he's reelected, and whether he it may be possible that he might take an even stronger stance on climate issues.

At their first debate, both Casey and McCormick spoke positively about the reopening of the Three Mile Island nuclear plant. (Photo: formulaone, Flickr, CC BY SA 2.0)

DOERING: And are we seeing any pressure from those young voters on Casey to promise more when it comes to climate and fracking?

BENSE: There's certainly pressure from environmental groups and from young voters in the state who would like to see Casey take a stronger stance on climate. They would really like him to take a stronger stance on things like fracking, on fossil fuel extraction, on liquid natural gas exports. He has kind of tried, as many politicians in Pennsylvania do to walk this middle line, and for environmentalists, they feel like that's not enough.

DOERING: You know, just recently, we reported on the proposed reopening of Three Mile Island to help power Microsoft's huge AI, artificial intelligence computing energy needs. To what extent have these candidates reflected at all on Three Mile Island reopening specifically and on nuclear power more broadly?

BENSE: The candidates were actually asked about this specifically during their debate on October 3, and it was one of the few areas where they seemed to somewhat agree. They both said that they were for reopening Three Mile Island, that they were pro nuclear power. I think Senator Bob Casey views nuclear power as part of a way that we are going to be able to transition to clean energy in the future. And then for Dave McCormick, he has really talked a lot about making Pennsylvania energy dominant again, and he likely views nuclear power as part of a portfolio to make that possible.

Kiley Bense is a Philadelphia-based reporter for Inside Climate News. (Photo: Brendan Bense)

DOERING: Now these candidates have both positioned themselves as for all of the above energy strategies. So to what extent has renewables, like wind and solar, how important have those been in Pennsylvania?

BENSE: This is an under talked about issue. So I did a story about this, kind of laying out questions that I wish the moderators would ask in the debate about energy and climate, and one of the questions that I would love to ask them both is what they would do to help position Pennsylvania better in terms of renewable and clean energy. There's been an influx of investment that's related to the Inflation Reduction Act and other legislation that was passed under the Biden administration, that was kind of earmarked for jump starting domestic production of clean energy in places like Pennsylvania and across the United States. But Pennsylvania is very far behind when it comes to clean energy investment, so we have a long way to go to catch up to other states. And I think part of the reason for this lag is because of our divided politics, it makes it harder for the legislature to agree on things and pass bills and make progress on issues like this. And even in Republican controlled states that tend to be very pro fossil fuel, they are making a lot more gains in clean energy than we are. I am the Pennsylvania reporter for Inside Climate News, so I care a lot about Pennsylvania, but I do think that what happens in Pennsylvania is really important, far beyond the borders of our state, in part because it's such a microcosm for the country. So the reasons that make Pennsylvania a swing state, it's very politically diverse and divided, it's also a big fossil fuel producer. And so if the United States, I think, is actually going to make progress on climate change and on transitioning to clean energy, states like Pennsylvania need to be part of that charge. And I think until we start to see real change in a state like Pennsylvania, we're not going to have real change at the national level either.

DOERING: Kiley Bense is a reporter with our media partner Inside Climate News, based in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Thank you so much, Kiley.

BENSE: Thank you.

Related links:

- Inside Climate News | “Fact Checking the Pennsylvania Senate Debate Claims on Energy”

- Inside Climate News | “Seven Debate Questions about Climate and Energy for Pennsylvania’s Senate Candidates”

- Inside Climate News | “Polling Shows Pennsylvania Voters are Divided on Fracking”

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

BirdNote®: A Bird in the Hand

The American Tree Sparrow, a common species in the Northern United States. (Photo: Tom Murray, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

O’NEILL: Pennsylvania is famous for its unusual town names, which include Burnt Cabins, Intercourse, Pillow, Chinchilla, Hazard and Panic. And there’s a story for how each got its name. In today’s BirdNote, Michael Stein shares how one small community came to be called “Bird-in-Hand”, Pennsylvania.

BirdNote®

A Bird in the Hand

Written by Bob Sundstrom

[ambient of Eastern bird songs in the background throughout]

STEIN: You’ve probably heard the old saying: “A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush.” Well, it’s a very old saying, and it’s gone through some changes over the years.

The phrase first pops up in a seventh-century Aramaic proverb, "Better is a sparrow held tight in the hand than a thousand birds flying about in the air."

A Northern Cardinal, famous for the red coloration in males. (Photo: Robert Engbird, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

An English book from the 15th century had this version:

It is more certain a bird in your fist than to have three in the sky above.

One hundred years later, there was another old English saying: “Better one byrde in hande than ten in the wood.”

In each era, the pragmatic wisdom is clear: Hold on to the sure thing rather than taking a gamble on something better.

The old saying eventually made it to Pennsylvania, where there’s a town named “Bird-in-Hand.” Legend has it that when two road surveyors in the early 1700s were trying to decide whether to stay the night where they were working or head back to Lancaster, one cited the bird-in-hand proverb. They decided to stay, and the place was named “Bird-in-Hand.”

I’m Michael Stein.

The American Goldfinch collects thistle seed, which can be both eaten and used for nest building. (Photo: Rob Kleine, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

###

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Sallie Bodie

Editor: Ashley Ahearn

Associate Producer: Ellen Blackstone

Assistant Producer: Mark Bramhill

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. 110222 recorded by ML W Hershberger WV May

BirdNote’s theme was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

© 2019 BirdNote December 2019

ID# language-09-2019-12-16 language-09 Narrator: Michael Stein

https://www.birdnote.org/podcasts/birdnote-daily/bird-hand

O’NEILL: For pictures and more, flap on over to the Living on Earth website, loe.org.

Related links:

- Find this BirdNote® and more BirdNote® Daily episodes

- Learn more about Bird-in-Hand in Pennsylvania

- Visit All About Birds, a Bird Identification and Education Platform by Cornell Lab of Ornithology

[MUSIC: Cathy Fink and Marcy Marxer, “Buffalo Gals / Puncheon Floor,” From Virtual Concert for their fans at the Jones House Cultural and Community Center in downtown Boone, North Carolina in 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ysQIgA6lTmg]

DOERING: The outcome of the 2024 US presidential election could profoundly shape the future of the climate and environment both at home and around the globe. What issues are you most interested in having us cover? Let us know by sending us a written or audio message at comments@loe.org. So, email us, at comments@loe.org!

O’NEILL: Coming up, environmental justice advocates in Cancer Alley appeal their case after a disappointing ruling in the lower court. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Eric Tingstad, “Skamania” on Mississippi, by Eric Tingstad, Cheshire Records]

Environmental Racism Case Appealed

The Dow Chemical Company facility near the Mississippi River in Hahnville, Louisiana. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

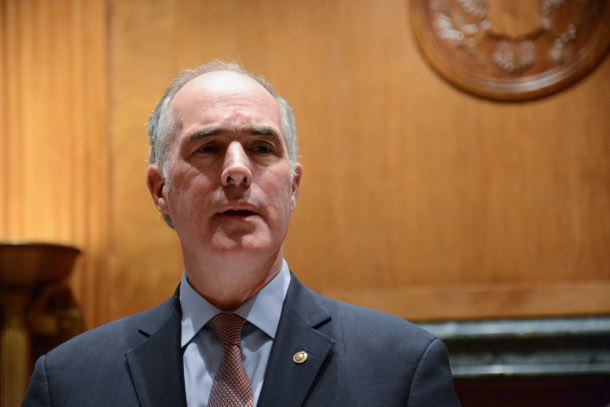

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill. The mix of industrial plants and residential neighborhoods along the banks of the Mississippi River between New Orleans and Baton Rouge is commonly known as Cancer Alley, and it’s a hotspot of environmental injustice. According to a 2023 study published in Environmental Challenges, toxic emissions in Louisiana are 7 to 21 times higher in communities of color compared to white communities. And chemical manufacturing is the largest contributor to this disparity. Community organizers in Cancer Alley have sued local parish governments and the petrochemical industry several times over the years. Just last year, Cancer Alley residents filed a lawsuit in Louisiana’s federal court alleging environmental racism and calling for a moratorium on new heavy industry and related infrastructure in St. James Parish. The lawsuit was dismissed but the plaintiffs appealed. And earlier this month, a three-judge panel at the mostly conservative US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit held a hearing. Here to discuss is Inside Climate News reporter James Bruggers. Welcome back to Living on Earth Jim!

BRUGGERS: Thank you very much.

O'NEILL: Now you've visited St James Parish. Can you describe it for us?

BRUGGERS: Yeah. So it's a significant part of a region in Louisiana that is known as Cancer Alley, and this is former sugar cane plantations that are lined up along the banks of the Mississippi River. And all Cancer Alley is about 100 miles long, and it runs between New Orleans and Baton Rouge, or thereabouts. And there's some 200 industrial facilities like oil refineries and plastics plants, chemical plants and other factories, and their harmful air pollution endangers residents health there. When you drive through the region, you see a lot of smokestacks. You see these flare stacks where there's kind of flames atop pipes that are at industrial sites. You see a lot of pipes and a lot of tanks.

A pipeline crosses Highway 18 in St. James Parish, Louisiana. (Credit: James Bruggers)

O'NEILL: So last year, in 2023 several community groups, Inclusive Louisiana, Mount triumph Baptist Church and Rise St James, all brought forward a lawsuit against the parish government. What were the plaintiffs asking for here?

BRUGGERS: What they're asking for is for their local government to stop sending industrial facilities to the predominantly Black districts that are in St James Parish. The lawsuit is about 150, 160 pages long, and it's really interesting. It traces Black history since European settlement in the 1700s through the legacy of slavery and post Civil War racism. It asserts that the parish government or the county government intentionally direct industry towards these Black residents and away from White residents. There's five electoral districts in the parish, two of them are predominantly black, three of them are predominantly white. And in recent decades, this lawsuit claimed that as many as 20 some of these industrial facilities were permitted for the two black districts and none were permitted for in or near White districts. In fact, the lawsuit says that no new industrial facilities have been allowed to locate in the majority white parts of this parish in the last 46 years.

O'NEILL: And as I understand it, that lawsuit was rejected.

Gail LeBoeuf, a lifelong member of St. Michael Catholic Church in St. James Parish and co-founder and co-executive director of Inclusive Louisiana. (Credit: James Bruggers)

BRUGGERS: Yeah, so the trial judge, the lower court judge, determined that the several claims that were in the lawsuit that the plaintiffs didn't have legal standing, and the judge also essentially said that they had waited too long after a 2014 land use plan, which was the parish's first land use plan, had been enacted, they waited too long to sue. So it was a lack of legal standing and essentially a statute of limitations arguments that prevailed in the lower court,

O'NEILL: And now, after this lawsuit was rejected, the plaintiffs have now appealed. What are they asking for in the appeal?

BRUGGERS: Well they want the Appeals Court to overturn the lower court ruling so that they can have their day in court themselves. They want to trial, and they want to take their claims before this lower court judge and make a case so that ultimately what they're seeking is they want to stop new heavy industry from being located in their districts.

O'NEILL: And now take us to the hearing itself. What are some of the major points that came up in this recent appeals court hearing?

Co-founder and co-executive director of Inclusive Louisiana, Barbara Washington, speaks at a New Orleans briefing on environmental justice in 2023. (Credit: James Bruggers)

BRUGGERS: Yeah sure. So one of the issues was access to and protection of graves of slaves that are found on either existing or proposed chemical plant sites and this is an issue that was argued on religious freedom grounds. One of the judges was a little critical about this issue and pointed out to the plaintiffs that those graves were not on parish property, not on public property, so why should that be an issue in this lawsuit. And questioned also how parish officials could be responsible for them just by issuing a land use permit. And this judge had made a comparison to issuing a driver's license and then the driver goes out and gets in an accident, well, the state that issued the driver's license isn't responsible for whatever happened in that accident. So the lawyer representing the environmental justice groups countered that the two scenarios were extremely different, and that the act of issuing a permit is done knowing that there could be damage to land where the graves are located, because you're issuing a permit for activity that would occur at a specific site. So that was one of the issues. Another issue had to do with a solar farm moratorium that the parish had passed at the request of White residents. So White residents had gone to the parish government and said they didn't like these solar farms that were proposed for their neighborhoods and so the parish government passed the moratorium. When black residents asked for a moratorium on new chemical plants, the parish declined. So this was an interesting argument on the part of the parish, because the lawyer for the parish countered by saying, well, there was no official act to contest here with the industrial moratorium request because the parish council never even put it on their agenda. So there was no official act that they could contest. And then the other issue was the statue of limitations, and the attorney for the parish had argued successfully in the lower court persuading the judge to rule that the statute of limitations on suing over that 2014 land use plan had passed, you would have had to have acted within one year. So the parish in the appeals court case, or an appeals court hearing, said that should continue. But interestingly enough, there was one of the appeals court judges, Judge Haynes, who pushed back on that a little bit, saying that discrimination can occur even after an initial act, such as approving a land use permit.

A graphic showing estimated cancer risk in Louisiana’s parishes. (Photo: Courtesy of Inside Climate News)

HAYNES: Again, I'm not saying I necessarily agree or disagree. I'm just trying to understand y'all argument that basically makes it sound like if you didn't sue within a year, well, heck, you can be discriminated against in a bunch of different ways for the rest of eternity.

BRUGGERS: Really, she kind of said hypothetically or possibly or could, she was not taking any position one way or the other, and then posed this question this way, she said, you know, if you fail to sue within a year, you can be discriminated against for the rest of the eternity, right? So that was that issue.

O'NEILL: So it sounds like this case is sort of an example of the zoning injustices that exist throughout the country.

BRUGGERS: Yeah. So this case has focused a lot of attention, particularly a lot of media attention, on long term impacts of decisions that were made decades or longer ago about certain land use practices that led to segregation, and then the resulting environmental impacts that come when you have various kinds of development or freeways or chemical plants or whatever in those areas. And I mean, this is something I see even in my own community, where I live in Louisville, Kentucky, and you can look where freeways were built, and you know, whole range of different problems. So practices such as redlining, which is like denying people access to credit because of where they live, for example, or deed restrictions on homes that effectively kept white neighborhoods white, decisions that put heavy industry into areas where poor and minority residents lived, all of these have been experienced all over the country. It's just that when you're in this chemical corridor, they seem more pronounced, and then you have the additional layer of very potent layer of slavery and the impacts of that, the legacy impacts of that on top.

Environmental justice advocate Sharon Lavigne, founder of the group Rise St. James, inside St. James Catholic Church in St. James Parish, Louisiana. Lavigne is a lifelong member of the church. (Credit: James Bruggers)

O'NEILL: So the organization Rise St James is one of the plaintiffs in this case. And last year, you spoke to the founder, Sharon Lavigne. What did she have to say about this fight?

BRUGGERS: So I went down to St James Parish and visited her, and went with her to church. She's a woman of faith, and I talked with her about how it's faith that moved her to get involved in the environmental justice battle to begin with, and how she had felt called by God to do what she's doing, and it's her faith that keeps her engaged in the battle. Inclusive Louisiana is also a faith based group and is run by two women, Barbara Washington and Gail Leboeuf, who also have told me that it's their faith that keeps them working for environmental justice as well. And the other plaintiff in this case is Mount Triumph Baptist Church in St James, led by Reverend Harry Joseph. I visited Pastor Joseph in his church. It's a very small church, and there I found a photo of the late Reverend Martin Luther King Jr and his wife, Coretta Scott King, hanging on the wall as inspiration. And I learned through this process of visiting them that it's really faith that has moved the environmental justice movement in this country from the beginning and they see it's faith that will carry them to some sort of victory, whatever that looks like.

O'NEILL: Well so now that this appeal is being made, what are the next steps? When are we going to find out something new in this case?

James Bruggers covers the U.S. Southeast as part of the Inside Climate News National Environment Reporting Network. (Credit: James Bruggers)

BRUGGERS: Well, I'm not sure exactly when we'll find out something new, but if their appeal is rejected, then the plaintiffs will have to make a decision on whether they want to attempt to take it to the Supreme Court or not. If the plaintiffs get what they're hoping for, the case will be sent back to the lower federal court for a trial and then the environmental justice advocates in St James Parish will have their day in court.

O'NEILL: Jim Bruggers is a reporter with our media partner Inside Climate News. James, thank you so much for taking the time with me today.

BRUGGERS: Thanks a lot, I appreciate it.

Related links:

- Inside Climate News | “Appeals Court Hears Arguments in Case Claiming Environmental Racism in Cancer Alley Zoning”

- New Orleans Public Radio | “'Cancer alley' residents ask federal court to revive lawsuit over new chemical plants”

- Center for Constitutional Rights | “Landmark Environmental Racism Case: Cancer Alley Residents Argue in Court for Moratorium on Toxic Plants in Black Districts”

- Inside Climate News | “On the Frontlines in a ‘Cancer Alley,’ Black Women Inspired by Faith Are Powering the Environmental Justice Movement”

[MUSIC: Marcus Ahlback, “We Shall Overcome” by Charles Albert Tindley, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LypCMSScgF0]

Eagle!

A panic of American herring gulls alerted Lender to the eagle’s presence. (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

DOERING: Rise early in the morning and head out to a nearby national wildlife refuge, and you’ve got a good shot of being rewarded with the sights and sounds of all kinds of birds. And on this birdwatching trip, you might be watched back. Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender reports from Stewart B. McKinney National Wildlife Refuge on the Connecticut coast.

Eagle!

Bald Eagle

Stewart B. McKinney National Wildlife Refuge

© 2024 Mark Seth Lender

All Rights Reserved

LENDER: From here to the west of us as far as I can see every herring gull has taken to the air. Only one thing does that.

“Eagle! Valerie!”

She comes running and we stand on the porch, passing the good binoculars back and forth, straining our eyes.

Nothing.

“Are you sure?” She says.

“They’re sure,” I say.

The gulls can see an order of magnitude better than we can and I trust their eyes over my own. To say nothing of their caution.

One minute, three minutes…

Valerie sees him before I do.

“There,” she says and hands me the binoculars.

Adult male. Smaller, more compact than a female. White tail. White head. Eyes that look almost full front. Huge yellow beak. Six feet of span together with the length of those flight feathers means he pulls a lot of air, the wing beat deceptively slow. He covers the distance in no time.

And looks right at us.

Mark Seth Lender spotted an eagle early in the morning. And the eagle spotted him. (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

It’s 6:30 in the morning, the summer folk vacated and gone and we are the only humans out at this hour, but even so. He can see even better than the gulls. But why he bothers to look – can’t say. He’s not in competition with us, not threatened. We are in the middle of the Stewart B. McKinney National Wildlife Refuge, he has no experience of harassment here much less harm. It is not a look of concern. Maybe, just the fact he’s here, by himself, we are here, by ourselves. Maybe, that’s all that life needs. To be worthy of a look. To draw attention.

I put the binoculars down now, he’s close enough they are not needed and we watch each other, not too different from medieval knights, raising their visors in salute.

DOERING: That’s Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender.

Related links:

- Read the Field Note for this essay

- Learn more about the Stewart B. McKinney National Wildlife Refuge

- Much of the wildlife of the Stewart B. McKinney can be seen at Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife

- Explore more of Mark Seth Lender’s work

[MUSIC: Stjepan Hauser/Brooklyn Duo, “Canon in D (Pachelbel's Canon) - Cello & Piano” arr. Hauser, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ptk_1Dc2iPY]

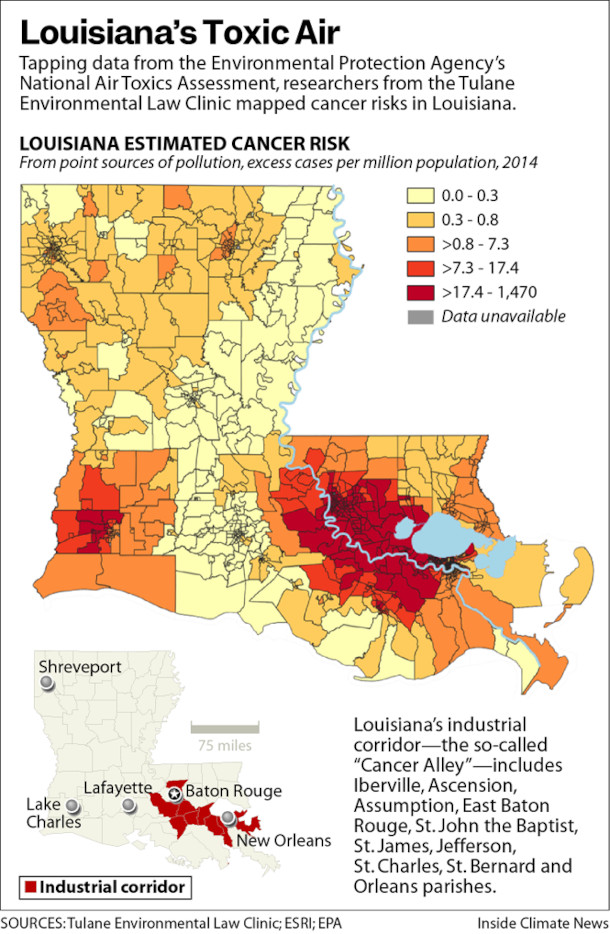

Europa Clipper On Its Way

The Europa Clipper spacecraft undergoes installation of its five-panel solar array in August 2024. (Photo: NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

O’NEILL: After the break we’ll journey to the icy world at the bottom of our planet, Antarctica. But first a quick note on a journey to another icy world that just lifted off. On Monday, October 14th the biggest interplanetary spacecraft ever built by humans blasted off into space. The precious payload of the Falcon Heavy rocket was Europa Clipper, which NASA engineers designed to gather data that could indicate whether Jupiter’s moon Europa might harbor life.

Europa is not exactly Earth-like. For one, Jupiter’s powerful magnetic field zaps its moons with huge amounts of radiation that would be dangerous to us humans. Europa is also so far from the Sun that it receives only about four percent of the sunlight that we enjoy on average. And because of that daytime highs on Europa are a balmy negative two hundred ten degrees Fahrenheit, and nighttime lows can get down to negative three hundred seventy Fahrenheit!

But beneath its thick icy shell, Europa likely has a huge liquid water ocean that just might provide the conditions for microbes to eke out a living. NASA plans to put Europa Clipper on a very elliptical orbit around Jupiter, which will allow it to make dozens of close flybys of the icy moon. But we’ll have to be patient, because it’s expected to take until 2030 just for Clipper to reach Europa. To get that far out into the solar system, the spacecraft will need a couple of gravity assist boosts from Earth and Mars. So if all goes well Europa Clipper should be back in our neighborhood around the end of 2026 before it’s on its way for good.

Related links:

- NASA’s Mission Page for Europa Clipper

- Listen to LOE’s previous coverage of the Europa Clipper mission, including a reading from US Poet Laureate Ada Limón of her poem “In Praise of Mystery: A Poem for Europa”

[MUSIC: The Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra/Sir Charles Mackerras on Youtube.com, “Jupiter” from The Planet Suite, by Gustav Holst, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gu77Vtja30c ]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Barbara Higbie, “Land of Gold” on Presence, by Barbara Higbie, Slow Baby Music BMI]

Journey to a Melting Glacier in Antarctica

Thwaites glacier surrounded by sea ice. (Photo: Elizabeth Rush)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill. The so-called “Doomsday” glacier in Antarctica known as Thwaites holds enough ice that its melting could raise sea levels worldwide by 2 feet. And seas could rise 10 feet or more if the loss of Thwaites destabilizes the massive West Antarctic Ice Sheet that it’s holding back. But because the climate is entering uncharted territory in human history, most climate models don’t account for that amount of sea level rise. So to help fill the data gap, in 2019 a few dozen scientists and crew made the long and stormy journey to Thwaites. Also on board their ship were a couple of journalists and the expedition’s writer-in-residence Elizabeth Rush. Her 2023 book The Quickening: Creation and Community at the Ends of the Earth chronicles the two-month expedition. But The Quickening also weaves in Elizabeth’s personal story of another epic journey.

RUSH: The amount of paperwork you have to do to go to Antarctica is like astronomical, and I can still remember getting this sort of like huge packet in the mail and reading one sort of line in it that said, pelvic exam. And it turns out that pregnant people aren’t allowed to deploy to the ice. I had really wanted to start trying to get pregnant around this time.

O’NEILL: And putting that off would mean Elizabeth would be 35 when she could finally start trying for a baby, right on the edge of the supposed “fertility cliff,” though she points out that’s somewhat of a myth. But the ice was calling, and she sensed it had a story to tell about what was happening to our rapidly changing planet, the very world she hoped to someday bring a child into. Elizabeth Rush joined Host Steve Curwood to talk about the journey to Antarctica and what it revealed.

The cover of The Quickening: Creation and Community at the Ends of the Earth. (Image: Courtesy of Elizabeth Rush)

CURWOOD: The subtitle of your book calls this the "Ends of the Earth," Antarctica. And you have a pretty strong telling of how difficult it is to get to the Thwaites Glacier. Talk to me a bit about the geography of this place and what makes it so doggone difficult to get to.

RUSH: Oh gosh, I remember when I accepted the invitation from the National Science Foundation, my program officer said to me, "You know, it's going to be easier for us to get help to folks at the space station than it will be for us to get help to you guys when you finally reached Thwaites. Are you sure you still want to go?" And I was like, "Yeah, of course I want to go!" And [LAUGHS] I really had no idea how far away this place would be. It literally took us a month to arrive. We were on an icebreaker called the Nathaniel B. Palmer that set sail from Punta Arenas in Chile. And the Palmer's about the length of a football field, so you can walk it from end to end in under a minute. From southern Chile, we sailed out the Strait of Magellan, and then started to cross the Drake's Passage, which is considered the wildest, most predictably wild ocean in the world. Basically, it's kind of the choke point between South America and the Antarctic Peninsula. And so all of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current that swirls around Antarctica gets squeezed right there. And so you tend to get really heavy high seas and big storms. Our crossing was pretty eventful. We had regular sort of 25-foot swell. At one point, you know, like, a gigantic refrigerator in the lab became untethered from the ship and, like, slammed across the lab. And we had to, like, strap it back down. Most people got really horribly ill during our crossing. And then you get across the Drake's Passage, and then suddenly, you're in iceberg territory. Our ship, an icebreaker, is made to ride up on top of ice floe, which is relatively flat sea ice, and then it kind of causes the ice floe to crack beneath it. It's not made to like run into an iceberg. So then we had to cross a bunch of big sea ice fields for days. And right when we first arrived at Thwaites, we then had a medical emergency on board that caused us to have to reroute to Rothera Base for 10 days, and then come back. So it did take us a month to arrive, which was wild.

An iceberg drifting in the ocean as the Nathaniel B. Palmer makes its way to Thwaites glacier. (Photo: Elizabeth Rush)

CURWOOD: So given how difficult it is to get an expedition down to this part of the world, why were so many scientists keen to go there -- and writers, too?

RUSH: Thwaites really is considered ground zero for the possibility of accelerated sea level rise this century. And yet, I mean, no one in Earth's history before us had ever been to the place where the glacier discharges ice into the sea. So we don't know basic, basic things like, how warm is the water circulating beneath Thwaites? How strong are the currents pushing that water under the ice? So the reason Antarctica, and in particular, West Antarctic glaciers are so vulnerable to our changing climate is not because they're melting because of atmospheric warming. They're melting because there's this warm water that's circulating beneath them, eating away at the ice from below and causing it to become physically unstable, which just has the potential to give you a rate of retreat and collapse that outpaces significantly glacial retreat, as we normally think of it, where you have kind of atmospheric warming above causing the ice to melt. Thwaites is sort of like a house of cards. And we're concerned as we lose some of the base, or the underside of the glacier, you're taking cards out of that house, and you could cause it to become so unstable that the whole thing falls apart really quickly. And I think one last kind of nerdy thing that's useful to know is that, you know, we know from studying different geologic records that in Earth's history, let's say like 15,000 years ago, roughly, there were rapid pulses of water into the ocean that caused sea levels to rise 50 feet over a couple hundred years. These events are called meltwater pulse 1A and 1B. And the supposition is that a significant portion of the ice that's causing that rapid, accelerated sea level rise is coming from Antarctica. But no human beings have ever lived through or recorded those events. Like, we know that they happened, but we don't really know what caused them. We don't know the drivers or the mechanisms behind that change. And so I think in the scientific community, at this deep level, there's a question, like, if we lose Thwaites, are we in the meltwater pulse 1A territory? Are we thinking about a rapid acceleration of sea level rise that's not really in our models -- yet.

Thick ice floes often slowed the icebreaker’s progress. (Photo: Elizabeth Rush)

CURWOOD: Liz, take me to the moment that you first set eyes on Thwaites, it's in your book on page 200. Please set it up first.

RUSH: Yeah, so this is just a short passage that's really about the morning of our arrival. And it starts, I guess, a few hours before we arrive. And I remember this evening really well, and I remember almost feeling like a kid on Christmas. You know, when you wake up and you're like, Is it Christmas yet? And you're like, No, it's 11:15 at night, Okay, I gotta go back to bed. And then you wake up two hours later, and you're like, Is it Christmas yet? And you're like, okay, it's 1:12, and then you go back to bed. That was what this night was like for me. [READING] That night, sound sleep eludes me. I wake often, each time hopeful that we have arrived. Finally, around five o'clock I rise, shuffle up the four flights of stairs, undog the door by the ice tower and walk out onto the bridge wings. Thwaites' gray margin wobbles in the gloaming. We wind alongside, entering small coves and rounding odd promontories, our pace slow to hold this precarious line. The ice face soft as dunes. The night's new hint of darkness gives way to the bruised light of dawn, and many others appear to watch what each of us has been working towards, for weeks, for years, and in some cases, for decades, come into sharp focus. We don't talk. When someone wants to say something they whisper, as though we're in a giant, roofless cathedral. We, who have been at sea for so long, finally gaze upon the glacier that has already given us one another. Rick, the chief mate, stands attentive at the ship's helm, the captain next to him, steering us along the edges of Thwaites' unfathomable fracturing, its hemorrhaging heart of milk.

Penguins on an ice slab near Antarctica (Photo: Elizabeth Rush)

CURWOOD: Then soon, after navigating through previously unnavigable waters, there's a huge collapse of ice and you're witness to a radical and rapid change that happened almost just before your eyes. Tell me about that.

RUSH: Yeah, so we worked probably for about six days nonstop. When you're on one of these scientific missions, once you get to your field site, there's no off switch, the ship is really just cranking on all cylinders at all times. So we were doing science 24 hours a day for like six days nonstop. And then, suddenly, there were more icebergs in the bay; suddenly, the waters became a lot less easy to navigate. And everyone was sort of wondering what had happened or what had changed. And it turns out that, you know, a piece of Thwaites like 25 miles wide and 15 miles deep had literally broken apart alongside us and was basically discharging these massive icebergs into the very bay that we were sailing in. And I can remember seeing these, we got these aerial satellite images of our study area. And indeed it looked, you know, this ice shelf was solid one day and the next day it looked sort of like a belligerent teenager had, like, taken a baseball bat to a car windshield and shattered it into hundreds of pieces. And I saw those and I literally just ran up to the top deck to try to see this process unfolding right in front of me. And I stood up there for hours. And on the one hand, part of me when I saw that was like, "This is why we're here, right? Like, man, we're getting, like, we are really getting the right data right now. This will be really useful”. And then that's coupled with a, you know, a deep sense of, “what I wouldn't give for none of this to be happening. What I wouldn't give for this to not be falling apart in front of me." And the bizarre thing was that it was actually like the most, one of the most beautiful days of our expedition. The sun had finally come out, the air was, like, crisp and cold. And all of a sudden, there were these like lavender-faceted icebergs in the bay, and I could only see them as icebergs, I could only see them, you know, for the first time, not, not a sign of significant change. So I stood up there for many hours and kind of tried to witness what was happening. And I felt like I always fell a little short of being able to, to actually perceive it.

As the Palmer made its way along Antarctica’s frozen, rocky edge, penguins and other wildlife came into view. (Photo: Elizabeth Rush)

CURWOOD: So of course, this was a journey for you, Liz, in understanding life, motherhood, our place on the planet. And for the scientists, there was a lot of data for them to gather. What were the big scientific takeaways from this expedition, do you think, to Thwaites?

RUSH: Well, I think of a couple. One of the most significant things that we were able to accomplish when we were at Thwaites is that we sent a submarine beneath the ice shelf. And that submarine was able to give us some really important information about the temperature of the water circulating beneath Thwaites. The most significant finding there was that the water beneath Thwaites is actually a little bit cooler than scientists had calculated. And I think folks tend to want to celebrate that, it's like, "oh, the water's cooler, that's so great!" But just because the water is cooler, doesn't mean that the glacier is moving any less quickly. In fact, the glacier's deteriorating at the same rate, and its water that's not as warm that's causing that deterioration. So in many ways, this proves that the ice shelf itself is actually more physically vulnerable than we had been calculating. The other really significant findings from that submarine was that it also drew very close to the seafloor and created these incredibly detailed sonar images of the seafloor. And from them, one of the sedimentologists on board was basically able to reconstruct the retreat of Thwaites during a really significant event that happened sometime in the last two centuries. He basically kind of read the ridges on the seafloor. Through that information, he was able to calculate a maximum rate of retreat for Thwaites that is two to three times faster than we had previously calculated.

After a month of travel through stormy seas, thick sea ice and iceberg territory, the Palmer finally arrived at its destination, Thwaites glacier. (Photo: Elizabeth Rush)

CURWOOD: Before you go Liz, talk to me about the strong thread of community that's, that's in your book. You have scientists and crew working around the clock, cooking, measuring, fixing, surviving, I guess, a nail-biting medevac. I mean, that, can't tell the whole story here. But that was quite a, it took, A, a lot of time and B, it was rather harrowing.

RUSH: Yeah.

CURWOOD: Later on, we feel that you're surrounded by support as you bring your son into this world. How did you witness community on the ship? And how does that influence how you see this world working together on the climate dilemma?

Fractures permeate Thwaites’ edge, soon to calve new icebergs. (Photo: Elizabeth Rush)

RUSH: You know, so we were, there were 57 of us on board this boat. And we came from all over the planet. We're from the Philippines, from Brazil, from Sweden, from the US. And we had this seemingly sort of impossible task, which was gathering information about this place that no one has ever been able to even reach before. And that we were able to do that, sort of, while existing inside of one of the most, you know, extreme environments on the planet, to me, was an absolute testament of what is possible when you work together with other human beings. In the climate conversation, it seems to me like there's been a bit of a shift in the past couple years, away from the kind of blame game narrative where you're an individual consumer and your decisions about organic or non-organic tomatoes, and cardboard packaging and plastic packaging is really where your, your impact on the climate crisis is going to be most profoundly felt. It seems to me like we're moving away from that, towards this idea that real climate action is going to be collectively achieved. But I don't think we have a lot of good stories that do justice to the ways that communities come together and are formed around shared concerns.

Elizabeth Rush is the author of The Quickening and Rising: Dispatches from the New American Shore, a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. She teaches at Brown University. (Photo: Stephanie Ewens)

And so one of my goals in writing this book was really to try to create a narrative that is not just about my singular expedition, but more about this community and the way they came together. So the book also has a pretty unconventional format in that, I don't know, about 50% of it is narrated in my first person, but my first person is regularly interrupted by the voices of my shipmates, and they're talking about their experiences on board. So if you were to flip open The Quickening, it kind of looks like a screenplay half the time. And I think it's important to know that what they say is, like, literally what they said on the boat. So I conducted 213 interviews while on board, and I hand-transcribed them all to create the archive that would, like, build the backbone of this story. And so it's my hope, really, that the book can be sort of like an experiment in storytelling that highlights collective labor. And it definitely, I mean, it definitely made me come home and think about how often I feel powerless in the face of the scale of the climate crisis. But when I feel that, I realize I have tools for combating that kind of desperation. And so for me, that's meant becoming much more involved in community organizing around just climate adaptation in Rhode Island. Any kind of collective climate action beyond the individual, I think, is, is where our power really resides.

O’NEILL: That’s Elizabeth Rush, Professor at Brown University and author of The Quickening: Creation and Community at the Ends of the Earth speaking with Living on Earth Host Steve Curwood.

Related links:

- Find a copy of The Quickening (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

- About author Elizabeth Rush

- Learn more about scientific research on Thwaites Glacier

- Listen to LOE’s interview with Elizabeth Rush about her previous book Rising

[MUSIC: John Butler, “Ocean” Single, Family Music Pty Ltd]

DOERING: Next week on Living on Earth, on a tiny sliver of Antarctica, a few hardy species of moss and other plants cling to life. But as the frozen continent rapidly warms, that sliver has grown more than tenfold since the 80s. The science behind the greening of Antarctica, next time on Living on Earth from PRX.

O’NEILL: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Kayla Bradley, Josh Croom, Daniela Faria, Swayam Gagneja, Sommer Heyman, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Nana Mohammed, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Allison Lirish Dean composed our themes. Special thanks this week to Ric Potvin, Refuge Manager of Stewart B. McKinney National Wildlife Refuge. You can hear us anytime at loe.org, Apple Podcasts and YouTube Music, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram @livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments@loe.org. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Jenni Doering

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill, Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth