December 6, 2024

Air Date: December 6, 2024

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Climate Action at the World Court

View the page for this story

The world’s biggest climate case is underway at the International Court of Justice at the Hague in the Netherlands. Over 100 countries and intergovernmental organizations are arguing before a 15-judge panel, which could decide to issue an advisory opinion to clarify nations’ obligations to limit global warming emissions. (03:16)

Why Exxon is Pro-Paris

View the page for this story

Major fossil fuel corporations including ExxonMobil are clearly stating they would prefer the U.S. remain in the Paris Climate Agreement, despite President-elect Donald Trump’s plans to take the country back out. Samantha Gross directs the Energy Security and Climate Initiative at the Brookings Institutions and explains to Host Jenni Doering how oil majors are making long-term plans for an energy transition. (08:10)

Plastics Treaty Delayed

View the page for this story

Crafting a UN plastic pollution treaty hasn’t been easy, with countries butting heads on key issues including curbs on plastic production, changes of the chemistry of plastics and the role of waste management. Maria Ivanova of Northeastern University has been a delegate or observer at the treaty negotiations since they began and joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss why the recent session in Korea that was supposed to finalize the treaty resulted in only a very rough draft. (09:24)

$250 Billion Yearly Economic Costs from Plastics

View the page for this story

Hormone-disrupting chemicals in plastics take a yearly economic and health toll in the hundreds of billions of dollars in the U.S. alone, according to a 2024 study. Pediatrician Leonardo Trasande discusses the research with Host Steve Curwood and explains why PFAS, phthalates, BPA and flame retardants in plastics are so harmful to human health. (15:54)

Giraffes in Trouble

View the page for this story

Facing habitat loss, poaching and climate disruption, giraffes have declined more than 40 percent in the last thirty years. The US Fish and Wildlife Service recently proposed listing three giraffe subspecies as endangered and two others as threatened. Danielle Kessler, US Director at the International Fund for Animal Welfare, and Host Jenni Doering talk about the threats to giraffes and how their proposed addition to the Endangered Species List could aid recovery. (10:12)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

241206 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Samantha Gross, Maria Ivanova, Danielle Kessler, Leonardo Trasande

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

Toxic plastic is costing our health and the economy hundreds of billions of dollars.

TRASANDE: There are downstream costs that are terribly important at a societal level, and we ultimately pay because the chemical industry contaminates us through the products we use in our daily lives and through the chemicals that are used in those products and in particular plastic.

DOERING: And health is an issue in the plastic treaty negotiations.

CURWOOD: Also, giraffes are facing increasingly tall odds in a warming world.

KESSLER: I think if you asked anybody to picture a safari in Africa, one of the first animals that's going to come to mind is the giraffe. They are so important and so critical to the ecosystems that we really need to ensure that we are protecting them.

CURWOOD: Those stories and more this week on Living on Earth—stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Climate Action at the World Court

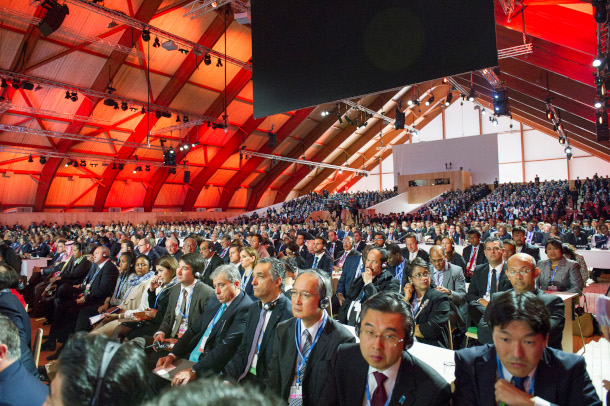

The International Court of Justice in the Hague, the Netherlands. (Photo: Andrea Brizzi, UN Photo, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

The world’s biggest climate case kicked off on December 2nd, before the International Court of Justice at the Hague in the Netherlands. Also known as the World Court, the ICJ was established after World War II as a mechanism for deciding disputes between member states of the United Nations.

DOERING: During this case, fifteen judges will hear from over 100 countries and intergovernmental organizations, each making their arguments on what international climate law obliges countries to do in the fight against climate disruption. The judges will then be asked to give an advisory opinion on that obligation, and the legal consequences for those who fail to comply.

CURWOOD: Though this opinion is not binding, it does clarify binding international law, like the UNFCCC's basis for the 2015 Paris Agreement. So, a favorable opinion could encourage cooperation with the UN climate treaty, which has struggled to limit global warming emissions.

DOERING: And it could also provide a legal precedent that could be cited at the national level, meaning that if the World Court finds that countries are obligated to fight climate disruption, then citizens could sue their own governments for failing to do so. The case was the brainchild of a group of law students from the University of the South Pacific in Fiji, who began a campaign to bring the case to the World Court back in 2019.

CURWOOD: To get onto the ICJ agenda, they approached the government of Vanuatu, a small island nation in the South Pacific Ocean that then led a coalition of over 130 UN member states to pressure the UN General Assembly into seeking an official opinion from the court. One of those original law students who developed the idea, Cynthia Houniuhi is from the Solomon Islands and spoke at the opening of the hearing.

HOUNIUHI: Climate change is undermining our ability to uphold the sacred contract. My people’s land of Fanalei is nearing a critical point on the verge of being completely engulfed by the rising seas. Without our land, our bodies and memories are severed from the fundamental relationship that define who we are. Those who stand to lose are the future generations. Their future is uncertain, reliant upon the decision making of a handful of large emitting states, which as my colleagues explained, are responsible for climate change. These states have not only enabled but proactively encouraged the production and consumption of fossil fuels and continue to do so today.

DOERING: The climate hearings in front of the World Court are expected to conclude on December 13th. A ruling will be closely watched not only for any impact on the climate treaty, but also other environmental treaties such as the Convention on Biological Diversity, and one proposed for plastic pollution.

CURWOOD: The biodiversity treaty recently suspended its bi-annual conference of the parties or COP, after it failed to find consensus on next steps. And delegates for the Plastic Treaty proposal recently failed to meet their own goal of creating consensus language for an accord by the end of 2024.

Related links:

- AP News | “A Landmark Climate Change Case Opens at the Top UN Court as Island Nations Fear Rising Seas”

- Watch the proceedings live on the UN’s website

[MUSIC: Joe Pass “Chloe” on Intercontinental, Edel Germany GmbH]

Why Exxon is Pro-Paris

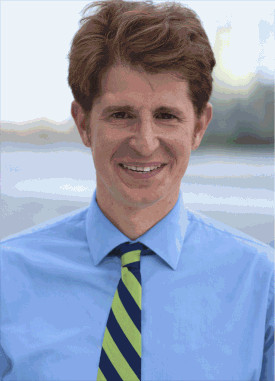

Exxon’s CEO, Darren Woods, disagrees with pulling the United States out of the Paris Agreement, noting that it could result in costly inconsistencies in energy policy. (Photo: Harrison Keely, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

DOERING: One of the big questions in the climate world is where the US stands now that a change in administration is imminent. President-elect Donald Trump has vowed to once again take the US back out of the landmark Paris Climate Accord. But major fossil fuel corporations including ExxonMobil are clearly stating they would prefer the US remain in the Paris Agreement. Here to help us understand why is Samantha Gross, director of the Energy Security and Climate Initiative at the Brookings Institution. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Samantha!

GROSS: Thanks.

DOERING: So why would Exxon warn against President elect Trump taking the US out of the Paris Agreement?

GROSS: Well, you know, one of the hardest things for energy companies, or honestly, anybody trying to make big investments in the United States, is when our policy changes a ton. It goes back and forth with changes in the administration. And so, I think part of the reason why big oil in general would kind of like to see us stay in is that they'd like to see some consistency in the US position on climate change, because they're not making four-year investments or even eight-year investments, they're making 20 and 30- and 40-year investments and they want a steady policy environment. And so, it's actually helpful for them to have the US be a little more steady in its climate policy, rather than swing back and forth. I also think it's a reputational thing for them. I mean, they don't want to be seen as encouraging us to pull out of this agreement that's so important for the world for dealing with the climate.

DOERING: And now I understand the oil industry as a whole is not actually a monolith when it comes to opinions on staying in or coming back out of Paris. What's going on there?

During his first presidency, Donald Trump pulled the United States from the Paris Climate agreement. He has said that he plans to do so again when he returns to office. (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

GROSS: No, the oil industry really isn't monolithic. And the way I like to think about it is the big companies that you and I and your listeners all know the names of, are one part of the oil industry, but there's a whole lot of smaller companies that operate regionally that don't have public names, that you and I and your listeners don't know about at all, and they often put themselves forward very different publicly. Part of it is because the big companies are big, and it's easier for them to do certain things. A lot of actions are easier to take with economies of scale if you're doing it over a lot of facilities. But in general, and across the board, because the smaller industry players don't have a reputation to protect, they don't tend to be as forward on climate issues as some of the larger companies. It's kind of funny that everybody likes to hate on big oil, but big oil is often more climate forward than some of these smaller companies. Not always, but often.

DOERING: And drill down just a bit, would you on why that is? Why are these big companies sometimes a little more attuned to their image in terms of carbon policy?

GROSS: Their image matters. I mean, I'm old enough to very clearly remember the Exxon Valdez incident, and that colors Exxon's reputation to this day. When bad public relation things happen, they're terrible for companies. So, you can think of it cynically as just a public relations thing, or you can think about that these companies are made up of people who live on earth who, in many cases, want to do the right thing. And those companies also tend to have a bigger balance sheet and more ability to try new things. It's easier for them to take action because they can have more economies of scale in doing it, and so often it's that those actions are easier for them than it is for some smaller operators.

DOERING: So, to what extent does this response from the big fossil fuel companies signify a shift in how we collectively approach an energy transition?

Donald Trump has stated he will roll back several of President Biden’s climate measures, including the electric vehicle tax credit and several policies under the Inflation Reduction Act. (Photo: The White House, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

GROSS: It's an excellent question. Clearly, fossil fuels are what's causing climate change, or a very central cause of it, and we have to remember that. But you also have to remember that these companies operate globally in a lot of countries that care about the climate, and they also want to be going concerns for a long time, all the way through the energy transition. And so, they're not just thinking about how do I make money today? They're thinking about, how do I make money in 20 years? And so, I think it's important to think of them as not necessarily the enemy, but as companies that also have some skills that can be used in the energy transition and big fat balance sheets that can be very helpful in doing big projects.

DOERING: And I understand that these oil companies are taking some steps to secure a role in a lower carbon future. What are some of those steps?

GROSS: There are some new technologies that are kind of naturals for oil companies to take on. A good example is carbon capture and storage. We tend to think of that as a way to sort of make fossil fuels last longer. But there are some places where it's very, very hard to replace fossil fuels and carbon capture may be a good idea. And if you think of what an oil and gas company is good at working in the subsurface, underground is exactly what they're good at. So, they have the skills to make these projects go. Another really good example is hydrogen. They already make hydrogen because they use it in their refineries and in petrochemical plants or thinking of using hydrogen for more things in the green energy transition. And they know how to do this. They can make it the old way and use carbon capture and storage. Or they can make green hydrogen using electricity but making and handling hydrogen and also just doing great big projects that take a long time and cost a lot of money. They're good at that, it's what they do now.

DOERING: If the US does leave the Paris accord again, and we're out for the next four years, what's left to be done internally? What are the major actions that we should be taking within this country?

Continued usage of fossil fuels and their resultant emissions have been identified as the major driver of climate change globally. (Photo: Ian S., Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

GROSS: I think the US will almost certainly pull out of the Paris Agreement, sadly, but there are a ton of things we can do locally. The Paris Agreement is actually not the main driver of our domestic action. And our automotive companies have geared up for electric vehicles. Our utilities are already installing mostly renewables. The IRA is the law of the land and has a lot of encouragement for continuing green actions. There are a lot of things that are moving forward, and they're not about the Paris Agreement, they're about domestic policy. So, I think it's a terrible bummer to take us off the world negotiation stage. But there's also a lot of momentum and a lot of actions here that are within our economy and not about the Paris agreement at all.

DOERING: Before you go Samantha, carbon emissions are higher than they've ever been, and the world is moving far more slowly to cut emissions than scientists prescribe. What message do you have for climate concerned folks who are frankly, might be starting to feel a bit hopeless?

195 parties, currently including the United States, are signatories to the Paris Climate Agreement, yet global temperature rise is unlikely to remain below limits set in the agreement. (Photo: United Nations, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

GROSS: I have a couple of messages. Yes, it is definitely true that we are not moving as fast as many climate scientists would like us to move. That's undoubtedly true and we need to keep pushing for investing in the technology we have, and we know that works, renewable electricity, geothermal electricity, reducing methane emissions. These are all things we know how to do.

Samantha Gross is the director of the Energy Security and Climate Initiative and a fellow in Foreign Policy for the Brookings Institute. (Photo: Courtesy of Samantha Gross)

And then we also need to push for greater research and development on the things we don't know how to do yet. So, we need to keep working. But to leave on a small note of optimism, it wasn't that long ago, 10 or 15 years ago, that we were on a trajectory that looked like maybe four degrees sea of warming or more, and it looks like we're now on a trajectory of two and a half degrees, maybe two and change. Is that where we want to be below one and a half degrees or two degrees? No, is it better than we were not very long ago? Oh, definitely. The curve is bending, it's just not bending fast enough, or the trajectory isn't changing fast enough. So, it's not that we've gotten nowhere. It's just that we're not going as fast as we need to be. And I think that attitude helps fight the hopelessness. It's not that we're not doing anything, it's just that we're not moving quite fast enough.

DOERING: Samantha Gross is the director of the energy security and climate initiative and a fellow in foreign policy for the Brookings Institution. Thank you so much, Samantha.

GROSS: My pleasure.

Related links:

- Politico | “Exxon’s Chief Has a Warning for Republicans”

- Bloomberg | “Russia Envoy Backs Paris Climate Deal, Hopes Trump Will Too”

- E&E News | “Carbon Markets — Safe from Possible Trump Attack — Could Expand”

- Scientific American | “Methane Leaks Are Everywhere. The Trump Administration May Repeal Penalty Meant to Reduce Them”

MUSIC: Joe Pass “Ode to Billy Joe” on Intercontinental, Edel Germany GmbH]

CURWOOD: Coming up, what’s next as the world struggles to assemble a plastic pollution treaty. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Joe Pass “Ode to Billy Joe” on Intercontinental, Edel Germany GmbH]

Plastics Treaty Delayed

Juliet Kabera, Rwanda’s Director General of the Rwanda Environment Management Authority. ICN-5 in Busan, South Korea, was meant to be the fifth and final negotiation session to create an internationally binding treaty on plastic pollution. No treaty was delivered, and the talks will resume some time in 2025. (Photo: Ministry of Environment, Flickr, CC BY NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

In 2022, the UN General Assembly voted to develop a legally binding international treaty on plastic pollution by 2024. But crafting that treaty hasn’t been easy, with countries butting heads on key issues including curbs on plastic production, changes of the chemistry of plastics and the role of waste management. And what was planned to be the final session of negotiations recently ended in Busan, Korea, with only a “Chair’s Text.” That's a very rough draft to guide delegates when negotiations resume, presumably in mid 2025. Maria Ivanova directs the School of Public Policy and Urban Affairs at Northeastern University and has been a delegate or observer at the treaty negotiations since they began. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Maria!

IVANOVA: Thank you very much.

CURWOOD: Maria, this was supposed to be the fifth and final negotiating session to create a binding international treaty to end plastic pollution. Didn't quite get there. How surprised were people that couldn't get finished?

IVANOVA: People were not surprised, but people were frustrated. We wanted to have an agreement achieved in record time. This would have been record time in two years to achieve agreement on a very ambitious global goal. But there were murmurs that it's too tight, it's too far, too quick. So not many people expected that we will be able to reach a final agreement. Yet most of us hoped that the outlines of an agreement would be agreed upon, but that was not possible.

Camila Zepeda, Mexico’s Chief Climate & Biodiversity Negotiator. The “High-Ambition Coalition” of over 100 countries called for curbing plastic production. (Photo: Ministry of Environment, Flickr, CC BY NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, talk to me about the major issues of contentions that have to be settled here. What seem to be the biggest sticking points so far in these negotiations?

IVANOVA: It is important to note that everyone, and I mean everyone, agrees that we do have a problem. We have a plastic pollution problem, and the sticking point was, where do we start? Do we start at the beginning of extracting fossil fuels from the ground that can turn into plastics? Do we start at the stage of design, or do we start at the time where we discard those products and improve our waste management systems? This is the key to the contention, is… Where does the life cycle start? And for the high ambition coalition, they said the life cycle starts at the extraction of these fuels from the ground. It starts at the beginning of even getting these resources. While for those countries that said we need a better waste management system, for them, the life cycle starts a bit later.

CURWOOD: Now the countries who are pushing for a better waste management system I would understand, are those countries that produce fossil fuels, the feed stock for plastic, at least a number of them, and I gather that there were a lot of fossil fuel lobbyists at these treaty negotiations. Just how powerful was their presence?

The “Like-Minded Ambition Coalition,” which includes countries like Saudi Arabia and Iran, argued that the treaty should solely focus on waste management. (Photo: Bo Eide, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

IVANOVA: You could see the presence of fossil fuel lobbyists in all of the spaces. There were also the chemical companies, and importantly, the brands were there. So, on the fossil fuels and the chemicals, the lobbying is for an agreement that does not limit production. On the brand side, and those are Nestle, Coca Cola, Unilever, you have a push for an ambitious treaty, and to me, they were much more visible than the fossil fuel lobbyists. They were much stronger in terms of a message, and much more aligned behind the message for a strong, ambitious plastics treaty, because the brands see that the consumers are changing their behavior.

CURWOOD: So, give me your take on the impasse there. As you say, there are those countries that want to keep pumping out plastics and treat this as a waste management problem. Others want to focus on turning off the tap or limiting production. What's your take on that debate? In other words, your opinion, how should this treaty end up, do you think?

Brands like Coca-Cola and Nestle are calling for an ambitious plastics treaty. Our guest Maria Ivanova suggests this may be because companies recognize shifting consumer preferences. (Photo: Dennis Godegebuure, Flickr, CC BY NC-ND)

IVANOVA: From the beginning, I saw that there were three options on the table. One, a no agreement option. The divergence was too wide, and we could emerge with no agreement. Two, an agreement of the willing, those who wanted to go far and quickly, and there were over 100 countries who wanted to have a global treaty that regulates the entire life cycle of plastics. But then it would not be universal. They would have to go out and have an agreement of the willing, and option three was a consensus pathway to bridge the High Ambition Coalition and the so called "like-minded" group, the oil producing countries that did not want to start at the beginning of extraction life cycle, but to focus on waste. And for that to happen, the high ambition countries needed to give in and eliminate production out of the agreement and start at the design stage. And the like-minded, then would have to agree to have chemicals in the design stage. This could have been a third option that would drive to consensus. In the end, we emerged with option one. There was no agreement. However, the talks have not been canceled. They have been suspended. And so, we will have option two and option three on the table in the future negotiations.

CURWOOD: So, there was this question of eliminating certain chemicals in the plastic production, which, of course, is still not decided. Maria, what are the health concerns with plastic pollution and the chemicals associated with it, for people and wildlife?

Maria Ivanova is the Director of the School of Public Policy and Urban Affairs at Northeastern University. (Photo: Alyssa Stone/ Northeastern University)

IVANOVA: The health concerns are wide ranging, and they're being discovered more and more with every passing day. Microplastics have now been found in the human body, from the brain to the blood to 100% of testicles tested, human and canine. Plastics have also been found in the deepest ocean, the Mariana Trench, and on Mount Everest. So, plastics are absolutely everywhere in the environment and in our bodies. So, the health effects range from cancers, Alzheimer's disease of microplastics in the brain, or stroke. The endocrine disruptors also are pretty significant, and there is a lot more to be discovered. Of course, you will hear the lobbyists saying, we need more studies, we need more research. And on the other hand, a lot of the scientists will say, we have the research, we know the health effects are significant, we need to do something about it.

CURWOOD: So, so far, no international plastics treaty, with negotiations to resume sometime this coming summer, in 2025. So how do you feel about this? Where are we as a planet in terms of dealing with plastics, from your perspective?

IVANOVA: Yes, no international treaty on plastics yet. But that doesn't mean there is no action on dealing with plastic pollution. The way I feel about this is similar to how I felt about climate when the Trump administration pulled out of the Paris Agreement, and that is, we are still in. This is what businesses wrote and published in the New York Times after the withdrawal of the United States from the climate agreement, and this is what I saw in Busan. Cities and companies are in. What I would like to instigate, to catalyze, is that campuses join that movement. I think if we empower, if we engage, if we catalyze action in cities, in companies and among campuses, we will have the basis not only for a plastics treaty, but for the necessary actions to deal with the plastic pollution problem.

CURWOOD: Maria Ivanova is the Director of the School of Public Policy and Urban Affairs at Northeastern University. Professor, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

IVANOVA: Thank you very much for having me back, Steve.

Related links:

- Read the “Chair’s Text”

- Read more about INC-5 in Busan, South Korea

- Read more about Maria Ivanova

[MUSIC: Bill Withers “Lovely Day” on Menagerie, Columbia Records]

$250 Billion Yearly Economic Costs from Plastics

Many chemicals used in plastics disrupt normal hormone function and can hurt human health, costing the US upwards of $250 billion a year in healthcare costs. (Photo: Laura James, Pexels)

CURWOOD: Researchers have tallied up the annual health and economic costs of toxins in plastics in the U.S., and it’s a huge toll, $250 billion a year. There are harmful chemicals in the plastics we use everywhere from food packaging, to clothing, furniture, cookware, and even nail polish. And they wreak havoc on the hormone systems of the human body, leading to devastating and costly health outcomes. A 2024 study published in the Journal of the Endocrine Society found that in 2018 alone, disease and disability caused by chemicals in plastic cost the U.S. a whopping quarter of a trillion dollars in health and economic losses. Lead author Leonardo Trasande is a pediatrician who directs the NYU Center for the Investigation of Environmental Hazards. Dr. Trasande, welcome back to Living on Earth!

TRASANDE: Thanks for having me again, Steve.

CURWOOD: So, your study focused on the costs of just a few of the thousands of chemicals that are used in plastics. What were the chemicals that you included in your study, and how do they threaten our health?

TRASANDE: So, we started by focusing on brominated flame retardants. Brominated flame retardants are best known to hack thyroid hormone. The baby relies on thyroid hormone through the second trimester of pregnancy, such that even low levels of thyroid hormone can disrupt brain development in the young child and have consequences that are permanent and lifelong. Then we also focused on phthalates, chemicals used to soften plastics that not only have effects on metabolism in adults as well as kids but disrupt sex hormone function and thereby can have effects on fertility. And these chemicals, particularly the phthalates, may have behavioral consequences not just for attention deficit, but for depression and other mental illnesses. We also looked at bisphenols used in polycarbonate plastic and aluminum can linings. Bisphenols are synthetic estrogens; they mess with fat distribution in the body by disrupting how cells in the body develop. Instead of bone or muscle, they become fat. And they disrupt the protective function of proteins that are important for heart function. And then finally, there are these forever chemicals, as they're called, per and polyfluoroalkyl substances, nonstick chemicals, that are used in oil- and water-resistant clothing, too. They do a host of things. They contribute to cancers, they disrupt metabolism, they can impair cognitive function. And the reason why these chemicals have such broad effects is they weren't designed with the human body in mind the way drugs are. And so, you mess with hormones, you have reverberations that cut across all sorts of organ function in the body.

Plastics can be found in unexpected places like furniture, clothing, and even nail polish. (Photo: Maksim Goncherenok, Pexels)

CURWOOD: And we have an obesity epidemic in this society. How might exposure to these chemicals and plastics be related to that?

TRASANDE: So, we used to think, simply calories in, calories out. And nothing I'm saying today mitigates the importance of diet and physical activity in the twin pandemics of obesity and diabetes in the U.S. and globally. But we know that chemicals can scramble our body's response to normal dietary cues. Take for example a study that followed a population of adults who had lost weight through healthy diet and physical activity. They drew a blood sample, they measured PFAS in that blood sample, and then they saw who gained weight back the fastest. The ones who gained the most weight back were the ones with the highest levels of PFAS. And then they dug in deeper, and they found that the resting metabolic rate of those adults had actually slowed down in relationship to the chemicals. So, talk about the body's thermostat being turned the wrong way.

CURWOOD: Now your study found that using these chemicals in plastics costs us some $250 billion in U.S. health costs a year, I guess you said maybe between 225 and 275. But it's still a huge number. So, what kind of costs did you include in those calculations?

TRASANDE: Well, to just start at the basic level, we looked at direct medical care costs, doctor's visits, prescriptions, emergency room visits, hospitalizations. But you have to dig deeper, because there are downstream costs that are terribly important at a societal level. And we ultimately pay, because the chemical industry contaminates us through the products we use in our daily lives and through the chemicals that are used in those products and in particular plastic. So just take lost economic productivity. A big driver of our costs was early death from phthalate-induced cardiovascular mortality. That's mortality during people's peak productive years. And so those are big dollar drivers, often over and above the cost of the medical care that you can count. Another example is when a child doesn't perform well in school, I might not notice as a pediatrician, the mother might not notice, the teacher might not notice. But if 100,000 kids lose an IQ point, the entire economy notices, because each IQ point is worth a 2% decrease in that child's ability to perform in the economy. And if somebody makes on average a million dollars over his or her lifetime, 2% of a million dollars is a big number, particularly when you multiply that by 4 million births in the U.S. each year.

Chemicals used in plastics like PFAS have been linked to obesity. (Photo: Andres Ayrton, Pexels)

CURWOOD: So, give me some context for this enormous number. I mean $250 billion. How big a deal is that?

TRASANDE: It's 1.2% of the gross domestic product of the United States. The chemical industry profits to the tune of $750 billion a year. So that's not even a great return on investment. That's a loss of 1/3 of that economic output as a result of disease and disability. When you put that side by side with U.S. healthcare costs, it's a bit of apples and orange comparison, I'm just going to be honest intellectually, but it's about 5%. In the big picture here, we looked at only maybe 10 or so chemicals used in plastic. There are thousands. And then we only looked at a subset of diseases due to the few chemicals we studied. And a subset of costs due to the few diseases due to the few chemicals we studied, so I'm afraid to say that the costs that we identify here, may actually be much, much bigger.

CURWOOD: This number, though, is one of those classic problems of externalities for pollution. Somebody makes products, spews it in the air or distributes it, but somebody else pays for the impact of that. And the plastic-making companies, they are profiting, well, let's face it, they make a lot of money from our addiction to plastics. So, if we can't get the companies to pay for these costs, who will? And actually, a sub-question of that is, what's the point of your research, pointing out this huge burden if no one's going to pick up the tab?

The stated figure of $250 billion in healthcare costs from toxic plastics is comprised of both direct medical costs and indirect economic costs, such as lost economic productivity due to early mortality. (Photo: Pixabay, Pexels, CC BY 2.0)

TRASANDE: Well, the point of the research is that we all pay the cost of the profit of the chemical industry in this case. And right now, countries across the globe are negotiating a Global Plastics Treaty. It's a landmark watershed moment in history where we can take on the challenge of the plastic threat to our planet. Now, there are some people out there, particularly from the chemical industry, that are pushing very hard to make the plastic pollution threat just a waste threat. They want you to focus on the Pacific Garbage Patch, for example. But we all have a little bit of that Pacific Garbage Patch in our bodies, and it's harming us, it's hacking our hormones and contributing to disease and disability. So, we not only need to get rid of waste from plastic, we need to reduce our use and production of plastics, period. That's going to face a lot of resistance from within the U.S. delegation because we produce, as an economy, a substantial amount of plastic, not just for the United States but for the planet. And we're only recycling 9%—lifetime—of plastics on our planet. The best rates of plastic recycling are 30%. And so, if we don't turn off the tap, what will happen is this plastic will accumulate even more in our bodies, and the disease burden that we're talking about will escalate even further.

CURWOOD: But be clear with me for a moment. If we were to recycle all of the plastic that's out there, to what extent will we still be at risk from disease?

TRASANDE: Even more, in an indirect way, because when you recycle plastic, you don't simply do a basic burn and reuse kind of operation, you add chemicals to it to make the plastic reusable. And the few studies that are out there have documented that chemical contamination in recycled plastic, including heavy metals, by the way, is higher than the virgin plastic. And so, we need to use the Global Plastics Treaty as a chemicals treaty. A lot of people want to just sweep the chemicals under the carpet. But there are tens of thousands of chemicals used in plastic materials to this day, of whom 12 or so have been regulated by existing environmental conventions globally.

Attendees of the 2022 United Nations Environment Assembly celebrate the passing of a plastics resolution, which called for the UN to recognize and address concerns related to plastic pollution. A Global Plastics Treaty is now being negotiated. (Photo: UNEP/ Cyril Villemain, Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, if I'm hearing you correctly, if you were in charge of everything, you would simply get rid of plastics from our society, at least the way that they're made right now.

TRASANDE: Well, I wouldn't get rid of essential plastic. There is a distinction here. I use the analogy of the cucumber wrapped in the proverbial plastic tight wrap. That cling wrap has no use. No logical use. During the pandemic, when I started flying again, I would see these tray tables be delivered to me with an extra two layers of plastic wrapped under the guise of well, I'm trying to prevent COVID by doing this. COVID is transmitted by air particles, not by droplets. So, it was the biggest plastic theater episode that I have ever witnessed. We seem to have gotten into the mindset that plastics is the future. Plastics have definitely provided crucial innovations to our life as a society. But the pendulum has swung way too far. We are excessively focused on profiting from finding any potential use of plastic in our life.

An art installation showing plastic waste flowing from a “tap” at the 2022 United Nations Environment Assembly. (Photo: UNEP/Ahmed Nayim Yussuf, Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

[MUSIC: Biff Smith, “Five of a Kind” on Biff Smith Solo Piano, by Biff Smith, self-published]

CURWOOD: We’ll be back after the break with more from our conversation with Dr. Trasande about reducing risks from chemicals in plastics. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Jimmy Smith/Thornel Schwartz/Donald Bailey, “Willow Weep for Me” on At the Organ, Volume 3, by Ann Ronell, Blue Note Records]

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Although the FDA banned Bisphenol A (BPA) in baby bottles and sippy cups in 2012, it did not prohibit the use of the chemical in water bottles and other plastic containers. (Photo: Andrew Seaman, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

We’re back now with pediatrician Leonardo Trasande with more about the enormous costs of toxic substances used in plastics. These chemicals are powerful endocrine, or hormone disruptors linked to health problems as varied as fertility issues, developmental delays and obesity, just to name a few. Even so-called bioplastics made from vegetable oils, food waste and cornstarch instead of petroleum are often laced with them. But there’s little regulation of the consumer products and food packaging that include chemicals such as PFAS, phthalates, and BPA.

TRASANDE: Well, we've generally failed, particularly when it comes to the Food and Drug Administration. Take BPA or Bisphenol A, for example. We knew that it was a problem back in 2008. So, the FDA banned it in baby bottles and sippy cups but didn't ban it in any other plastic materials. Let's go to phthalates now. The Consumer Product Safety Commission banned eight phthalates in toys or restricted them to a very low level. The Food and Drug Administration has only limited two of those eight. So, talk about a logical inconsistency. It's not as though kids don't eat food from packaging the same way they play with toys.

Bioplastic packing peanuts. Bioplastics come from biological sources such as starches or vegetable oils. Although they are sometimes advertised as safer than petroleum-derived plastic, they can also contain endocrine disrupting chemicals. (Photo: Christian Gahle, nova-Institut GmbH, CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: To what extent is dealing with this problem a bit of "whack-a-mole"? Because when one type of chemical is taken off the market, let's say Bisphenol A, industry comes up with Bisphenol S. How safe are the alternatives that industry has been putting forth when certain chemicals are identified as problematic.

TRASANDE: Unfortunately, the little we see is these are not safer. Bisphenol S is a prototype example. It's as estrogenic, as toxic to embryos and as persistent to the environment. Bioplastics are often proposed as a whole other alternative. But what little we know about bioplastics, which you would assume are naturally derived and safe, right? Nope. They are as endocrine active and endocrine disrupting as the chemically based plastic. There are safe materials. It's just that we have become aware of the many different ways in which things that we thought were safe are actually not.

CURWOOD: So, for someone who's listening to us right now and concerned about this, what steps can they take to protect themselves and our society as we wait for some sort of response from the politicians that govern our regulations?

TRASANDE: So, there are safe and simple steps we can take in our lives to reduce our plastic footprint and protect ourselves. If you need to use plastic, particularly don't machine wash or microwave plastic. The chemicals in some cases we're talking about are not covalently bound to plastic and the harsh ingredients and high temperatures can lead to degradation and eventually absorption of those chemicals into food more readily. Also, avoiding certain recycling number plastics is important because three is for polyvinyl chloride, which typically adds phthalates. Six is polystyrene, which breaks down into styrene, a known carcinogen. And seven is typically for polycarbonate plastics, which include bisphenols. But more generally, we can reduce our use of plastic. People use plastics in our daily lives when they actually could save money and save grief by using glass or stainless steel.

Dr. Leonardo Trasande is a pediatrician who directs the NYU Center for the Investigation of Environmental Hazards. (Photo: Cheryl Stockton)

CURWOOD: This is so overwhelming that a quarter of a trillion dollars every year, it's costing people in this country, in other words, every four years that's a trillion dollars, because of the health effects from plastics. It's a huge number, it's overwhelming. What gives you hope?

TRASANDE: What gives me hope is we've seen decreases in levels of these chemicals of concern over the past two decades. BPA levels, for example, have declined as attention to BPA-free materials has come into vogue. Now that's come with some unfortunate consequences, there are some replacements of BPA that are starting to come on the scene and detectable in people. But again, the awareness has fundamentally changed. And the more we keep growing awareness of this issue, people will use the power of the pocketbook or wallet to drive the change they seek. Ultimately, these companies are accountable to the consumer. So, it's the consumer that gives me hope, not to mention the fact that with the attention to climate change, particularly among Generation Z, you have a spirit of awareness that is there that hasn't been there before.

CURWOOD: Dr. Leo Trasande is a pediatrician who directs the NYU Center for the Investigation of Environmental Hazards. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

TRASANDE: Always a joy to be with you Steve. Thanks again.

Related links:

- Journal of the Endocrine Society | “Chemicals Used in Plastic Materials: An Estimate of the Attributable Disease Burden and Costs in the United States”

- Environmental Health News | “Chemicals in Plastic Responsible for Nearly $250 Billion Worth of US Health Costs in a Single Year”

- New York University | “Center for Investigations of Environmental Hazards”

[MUSIC: Open Road Folk Music “Light on The Mountain - Instrumental” on Instrumental Indie-Folk, Vol.2, alexrainbirdRecords]

Giraffes in Trouble

Giraffe translocation to the Kitenden corridor in Kenya. (Photo: Courtesy of IFAW)

DOERING: Giraffes are the tallest land animals in the world. These gentle giants can grow up to 19 feet tall and are found across savannas and open woodlands of sub-Saharan Africa. But as the population of people in Africa has tripled from 500 million to more than 1.5 billion since 1980, at the same time, habitat loss, poaching and the climate crisis have led to a more than 40 percent decline of giraffes. And in some regions, giraffe populations are now down to just a few thousand individuals. After years of petitioning from conservation groups to protect giraffes under the Endangered Species Act, the US Fish and Wildlife Service recently proposed listing three subspecies as endangered, and two others as threatened. Here to tell us more about what this could mean for giraffe conservation is Danielle Kessler, the US Director at the International Fund for Animal Welfare or IFAW. Welcome to Living on Earth, Danielle!

KESSLER: Thank you. It's so nice to be here with you today.

DOERING: What are the top dangers that giraffes face?

KESSLER: Yeah, so really, it's largely an issue of space. So, giraffes are large land animals. They cover and they roam large areas. Their primary activity during the day is grazing. They spend a lot a lot of time eating, as most of us in the US are heading into a holiday, we can also relate to that. And so, these giraffes they're spending most of their day moving and looking for… For ways to sustain their rather large body mass. So, they're oftentimes coming into areas where we also have, you know, significant human population growth across the African continent. And so, there's only so much space and only so much land, and as we are also seeing increased impacts of climate change, such as drought or extreme precipitation events, communities, people are moving. They're having to move larger distances and to find new places to themselves survive and to graze their livestock and to have resources for communities. And so, this, again, is moving into areas where wildlife populations might be, and so there's land use changes and habitat fragmentation that happens as a result of that human population growth, and then the displacement of those communities and populations based on these natural sort of impacts, or these climate change induced impacts.

DOERING: So, tell me more about drought and how climate change is impacting giraffes.

KESSLER: Yeah, as I mentioned, the sort of primary driver of the decline in giraffe populations is habitat degradation, fragmentation, and a lot of that is driven by these extreme weather events, be that drought or extreme precipitation. I mean, right now across Africa, we're seeing a lot of drought conditions. So, the dry spell in southern Africa, early this year was the worst on record in the 40 years that they have been keeping those data records. According to the UN World Food Program, there has been about a 70% decrease in the harvest in Zambia and 80% in Zimbabwe. So, we are talking about crops just being wiped out in some of these areas of Africa, and anytime that the communities then are losing their crop yields or livestock aren't as productive, and it's causing those communities to also have to move and to find other places. So as those communities move, they may come into areas that have been more historically wildlife areas, and so that habitat encroachment then puts the animals, giraffes, others in sort of direct competition for the limited resources with those communities.

Giraffe populations have been declining because of habitat loss, climate change and poaching. There are approximately 117,000 giraffes left in the wild. (Photo: Courtesy of IFAW)

DOERING: I understand that giraffe decline has been called a silent extinction. Why is that?

KESSLER: Yeah, it's one of those extinction events that I think has not been grabbing headlines quite like others. So, about a decade or so ago, we really saw a lot of headlines about the elephant poaching crisis, and we saw elephants being poached across Africa, and there was ivory trade, and there was transnational organized crime that was tied to these things, and the rhino horn trade. And so there was sort of these attention-grabbing headlines of what was driving these extinctions, because it was linked to sort of large-scale events that were causing these things. And giraffes on the other hand, like I said, it's been about four decades that we've seen this 80% decrease. So, it's been sort of a slow burn, if you will, and maybe not these flash in the pot, sort of events that grab headlines and really make news. And so, it has been sort of happening in the background and just hasn't been picked up as a sort of the crisis that it is.

DOERING: Yeah, it sounds like the frog in a pot of boiling water, perennial problem.

KESSLER: Yeah, absolutely.

DOERING: And I could see how, compared to the rhino being hunted for its horn being used for so called medicinal purposes, that's a little bit more of an attention-grabbing headline than giraffes declining because of habitat loss?

KESSLER: Yeah, I think if you asked anybody to picture a safari in Africa, one of the first animals that's gonna come to mind is the giraffe, and we still see them so commonly in photos of that and the landscapes and so again, I think there's almost a sort of recency effect, or really, since it come to mind so quickly, you think that there's not a problem, because we still see them, and we still associate them so much with Africa. Which is another reason that we really wanna strive, I mean they are so important and so critical to the ecosystems that we really need to ensure that we are protecting them.

DOERING: How would enlisting giraffes under the US Endangered Species Act help protect them?

KESSLER: Yeah, absolutely. It's a great question that it comes up a lot with regard to any time that the US is looking at listing foreign species, because the US obviously doesn't have jurisdiction to say what can be done with these species in other countries. But there are some benefits that these listings unlock, including increased funding that can go to range countries. So again, it sort of draws that spotlight. It draws international attention. It draws US attention to the fact that this is an extinction crisis, this is what's happening. And so, it can unlock some of those funding streams and ensure that conservation projects and… And things happening on the ground in Africa have the appropriate funding. And then it also puts a requirement on having permits for import of any giraffe specimens that might be coming into the US. So, we do know that there is fairly significant trade coming into the US. So, from a period of about 2006 to 2015 there were nearly 40,000 giraffe specimens imported into the US. So that includes things like bone carving, skin pieces, hunting trophies and so that 40,000 specimens, conservatively, is just under 4,000 individual giraffes. So, about a decade long period, about 4,000 giraffes coming into trade in the US. If that was all West Africa, it was not, but if it was all one of those species that would wipe out that entire species. So, ensuring that that trade is being done in a way that is not impacting these species, particularly the most endangered species, so we have a significant role in that, and making sure that we're not contributing to the declines is a really important aspect of this listing.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service proposed listing West African, Kordofan and Nubian giraffes as endangered. It also proposed listing Masai and reticulated giraffes as threatened. (Photo: Courtesy of IFAW)

DOERING: So more broadly, what would a Giraffe Conservation Program look like?

KESSLER: Yeah well, I mean, as with any conservation program that we're looking at on the ground, you know, the approach that IFAW takes, and what really we find to be effective approach, is ensuring that you're working with the communities that live alongside these animals. And so, there's displacement of people in communities as well as the wildlife that they live alongside. And so, it's a matter of making sure that we understand the whole of what is happening and the context, and working with the communities and those that live alongside these animals to ensure that you're coming to find opportunities for both people and the wildlife.

DOERING: It seems important. Because sometimes we've seen conservation end up pushing people out of, you know, areas where they might need to live.

KESSLER: Yeah, absolutely and the knowledge that communities have, it's so valuable. They are sort of the front line of dealing with these animals. They have incredible knowledge, and these animals can also benefit them, depending on how they are reviewed in terms of bringing in tourism, and it's an area that we need to be looking at as well from a larger sort of global community. How can we be supporting these communities that live alongside wildlife? The wildlife and the ecosystems that are supported in these areas are critical for all of us, for our survival. These animals, they help mitigate climate change, right? So, they are carbon sinks. They take it and they capture carbon, and so they can mitigate some of the most extreme effects of climate change. And so, preserving and helping ensure that these ecosystems and these charismatic megafauna and all biodiversity is preserved really helped protect us all, and so we all have a role to play in figuring out how we how we can incentivize that and ensure that the people living alongside animals are benefiting from them too.

Giraffes are known as gentle giants. They feed on leaves, stems, flowers and fruits. The giraffes pictured above are at the Thula Thula Private Game Reserve in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. (Photo: Courtesy of Andrew Skerritt)

DOERING: So, what's next for this listing process?

KESSLER: So next is… It's open now to a 90-day public comment period, so that'll be closing in mid-February. So, the agency will be taking information from nonprofits, from academics, and from the American public, or even from those overseas, from foreign governments, from really anyone who wants to provide input to this. The things that they're going to pay the most attention to is information that is scientifically based, that is information about the management of these populations in the countries. Things that really help them to base this decision in, is this the best for conservation? And so they'll be taking that information in, and then they're going to sit back and they're going to evaluate all of it, and they'll take a look at everything they received, and then they'll issue a final decision, hopefully that would be within the year, but that will largely be dictated by the next incoming administration and when that can sort of get prioritized in moving through the agency. So, it's a great time for certainly those who work with giraffes or around giraffes or conservation project, for those individuals with specialized expertise to really be weighing in, but also for the American public to be saying how they feel about this listing and whether they think the US should be active in protecting giraffes.

DOERING: Danielle Kessler is the US director at the International Fund for animal welfare, or IFAW, thank you so much Danielle.

KESSLER: Thank you. It was great to be with you today.

Related links:

- The Guardian | “US Moves to List Giraffes Under Endangered Species Act for First Time”

- IFAW | “Are Giraffes Endangered?”

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife | “U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Proposes Endangered Species Act Protections for Giraffes”

- Learn more about Danielle Kessler

[MUSIC: Sahara Skylight, “Speaking of Africa” on Spirit of Cape Town, Epidemic Sound]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Kayla Bradley, Josh Croom, Daniela Faria, Mehek Gagneja, Swayam Gagneja, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Nana Mohammed, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, and El Wilson.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Allison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and YouTube Music, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram @livingonearthradio. And we always welcome your feedback at comments, at loe dot org. I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth