August 15, 2025

Air Date: August 15, 2025

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Sounds of Soil

View the page for this story

Sounds like the overlapping songs of birds can speak volumes about the biodiversity in an ecosystem, and now scientists are looking to use the tiny sounds made by earthworms, ants, and voles to study the health of soils. Ecologist Carlos Abrahams joins Host Aynsley O’Neill to explain why more varied sounds appear to indicate healthier soils, and the potential applications of listening for these sounds in the earth. (07:37)

"Depaving" the Way to Greener Neighborhoods

View the page for this story

"Depaving parties" of volunteers with sledgehammers are turning paved yards into pollinator havens and green space. That can help reduce climate impacts from extreme heat and flooding. Living on Earth’s Sophia Pandelidis reports from Somerville, Massachusetts. (05:03)

The "Dirty Dozen" and "Clean Fifteen"

View the page for this story

Not all conventionally grown fruits and vegetables are loaded with high levels of harmful pesticides. To help consumers make efficient choices in the produce aisle, every year the Environmental Working Group puts together two lists, the “Dirty Dozen” and the “Clean Fifteen.” EWG Toxicologist Alexis Temkin talks to Host Steve Curwood about how to use them during grocery trips. (08:34)

Shiitake Mushroom Harvest

/ Aynsley O’Neill and Jenni DoeringView the page for this story

A year after inoculating a log with shiitake mushroom spawn and reporting about it on Living on Earth, Producers Aynsley O’Neill and Jenni Doering harvested and cooked up the first crop. Jenni Doering walks Host Steve Curwood through moments from the mushroom cooking adventure, which didn’t go quite as smoothly as planned. (07:16)

The Light Eaters

View the page for this story

A scientist who rappels down cliffs to hand-pollinate endangered plants. A vine that mimics the leaves of nearby species. Rice that crowds out strangers but leaves room for the roots of relatives. All of these are subjects of the book The Light Eaters by Zoë Schlanger, who tackles big questions of plant intelligence, consciousness, and communication. She joins Host Steve Curwood to talk about what we might discover when we look closely at the green life around us. (18:35)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

250808 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Carlos Abrahams, Zoë Schlanger

REPORTERS: Sophia Pandelidis, Jenni Doering, Aynsely O’Neill

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.“Depaving parties” aim to transform paved yards into pollinator havens.

MEUNIER: Ideally, when you can get pavement out, it increases not just more space for water to go, but it increases opportunities for planting gardens, for planting trees, for yards, for kids to run around and play park space, etc. It’s like, amazing.

CURWOOD: Also, astonishing revelations about plant intelligence and consciousness. One finding is that some plants can apparently feel pain.

SCHLANGER: So they handed me tweezers, we're in this dark microscope lab, and I pinch the plant with the tweezers, and suddenly there's this green eminence glowing from the place that I've pinched this plant, then it starts traveling down its vein system. And within about two minutes, the entirety of this little plant had received the signal of my pinch.

CURWOOD: We'll have those stories and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stick around!

[THEME]

Sounds of Soil

Listening to sounds in the soil is a minimally invasive way to measure biodiversity underground. (Photo: Courtesy of Baker Consultants Ltd.)

CURWOOD: From PRX, this is Living on Earth

From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is an encore edition of Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. When you step outside on a warm sunny day, you might hear birds chirping, squirrels chittering, or frogs peeping, but ecologist Carlos Abrahams spends his days with an ear to the ground. Carlos specializes in ecoacoustics, the study of sound in the environment. And his work focuses on finding a way to link the sounds of the dirt under our feet to soil health. Healthy soil needs biodiversity, so his work listens for slithering earthworms –

[EARTHWORM SFX]

--- marching ants –

[ANTS SFX]

And tunneling voles

[VOLE SFX]

-- with the idea that these signs of life can tell us just how well the soil’s doing.

Carlos Abrahams spoke with Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill.

O'NEILL: So, Carlos, what do we know about the link between soil sounds and soil health?

Dr. Abrahams’ research aims to use soil acoustics to help sustainable agriculture measure improvements in soil health. (Photo: Courtesy of Baker Consultants Ltd.)

ABRAHAMS: So, we think those two things are linked together. And we know that in other environments aboveground, we get good links between the sounds that are produced in an ecosystem and species diversity, species richness. That's been shown in various places around the world. So, taking that learning from aboveground, we're hoping to apply the same sort of principles to the sounds from soil as well. And it does seem to be, from the initial work that ourselves and other people have done, that where you have diverse sounds, that is a good indicator of good environmental health, good land management practice, and lots of fauna in the soil, so a biodiverse soil fauna. Where we have poor sounds within the soil and they aren't complex, and there's not much going on, then that's often an indicator, for example, of bare soil, or one that's been highly agriculturally improved, and had lots of chemicals put into it potentially. So, the work that we've done and other people have done have sort of given us a good nod in the right direction that if we take sounds from the soil and analyze those, they will be a good indicator for soil health, soil biodiversity.

O'NEILL: And so, once you have this recording, how do you learn from it? How do you figure out what that says about the soil?

ABRAHAMS: Okay, so these days, we have two main ways to take sounds from the environment and use those to study wildlife ecology. And one way is to try and recognize the individual voices of different birds or different bats or different sorts of soil fauna, whether that's earthworms or beetles. And aboveground, there's been lots of development of that. So, some of the universities in the States have done superb work in terms of building recognizers that you can now take a recording, hit it with their fantastic AI algorithms, and it will tell you what bird species it is. And we have similar recognizers that do that for bats as well. And we can do that pretty well for a whole range of different species underwater as well. The unfortunate thing is that we don't have enough recordings from known species within the soil at the moment to build up a library and a classifier to allow us to know what is making what sound. One of the big parts of the projects we're currently doing for the UK government at the moment with this grant scheme, is to try and do that. So, we have buckets of different sorts of worms, and we're trying to record one type of worm versus another worm versus woodlice versus centipedes, whatever it might be. So that's the first approach. The other approach that’s become available in the last 10 years or so is not to try to identify species, but to use an acoustic index that allows you to take a recording and analyze how complex the sound is within that recording. So we can take a one-minute sound file, and if there's lots of different things going on, there's lots of sound being produced, then we can give that a number. We're hoping that we can link that to good soil health or good land management practice. And if those sounds are very quiet, there's not much going on, then we know that there's not much fauna activity within the soil. And that's possibly, probably going to be related to poor soil health.

In addition to collecting audio from natural and agricultural environments, Abrahams studies the sounds from controlled lab environments. His team hopes to build a library of the sounds of individual species. (Photo: Courtesy of Baker Consultants Ltd.)

O'NEILL: It sounds like a lot of what you're learning from your ecoacoustics work might help in boosting soil quality, and specifically in the agricultural field at that. So, what kind of challenges are farmers currently facing with regards to soil quality?

ABRAHAMS: So, when we are looking at soil health, and we need to put air quotes around that, because it's not a very well-defined term, we can go and do physical measures. So, farmers are used to dealing with things like pH levels or alkalinity of their soil. But in terms of trying to assess the biodiversity within soil, that's really hard to do. And there are very few good methods that are available for that. The great thing about the soil recordings is that it's pretty lightweight. You can take lots of recordings across the field. It's quite easy to do. It's pretty quick. It's fairly cheap in terms of recording and analyzing those. And we're hoping to prove it gives a good indication of how healthy that area of soil is there without having to go to lots of effort or lots of expense. It's a new, hopefully potentially really useful and quite easy to implement system that gives us data on soil biodiversity that we can't really get very well using other methods. So, it's sort of filling a gap that farmers and other land managers are looking to try and fill at the moment. There's lots of interest in regenerative agriculture and improving soil health, how we manage soils, how we look after the environment. And new data sources, like using soil acoustics, are potentially really valuable in terms of allowing us to do that monitoring.

Researchers hope that soil acoustics can eventually be used to test the health of restored forests. (Photo: Courtesy of Baker Consultants Ltd.)

O'NEILL: Now, I want to zoom out a bit, because this field is really still in sort of its earliest stages, it sounds like. So, what do you see as sort of the next step in specifically the—the soil side of eco acoustics?

ABRAHAMS: We need to expand those little bits of work that have been done in soil across a wide range of environments and into new places. And get people aware of it and using it within their own contexts as well, whether that is, you know, within agricultural or nature conservation, or whether it's in the restoration of contaminated land, for example, or soil storage. So, we've had some approaches from building development companies who are interested in how what acoustics might tell us about soil that they have removed from the development site and stored for five or 10 years before reusing that soil for green spaces and planting within new developments. And is the soil still alive? Or is it completely dead when they're putting it back? Yeah, we're really at the start of trying to figure out how it all works, how we can use soil acoustics. The research that's been done has shown lots of promise, but really, there's a whole universe of work that still needs to be done to try and expand the boundaries of what we know.

CURWOOD: That’s Carlos Abrahams, senior lecturer at Nottingham Trent University, speaking with Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill.

Related links:

- Learn more about Carlos Abrahams

- Read about the importance of biodiversity

- Explore how ecoacoustics is being used above ground

[MUSIC: Buffalo Springfield For what it’s Worth Self-Titled release 1966 on Atlantic Records]

"Depaving" the Way to Greener Neighborhoods

Green and Open Somerville’s “Depave the Way” initiative aims to help neighborhoods adapt to climate change and increase green space. From left: Leigh Meunier (black vest), Eduardo Rodriguez (orange), Jack Briskie (light gray) and Depave the Way participants. (Photo: Green and Open Somerville)

CURWOOD: In the warm weather months, a 90-degree day every so often can be a nice treat.

But by 2070, the Massachusetts Bay Area will likely see almost 40 more of these days in a year than it currently does. And too much of a good thing can definitely have its drawbacks.

In the Boston area, the city of Somerville is particularly vulnerable. Over three-quarters of Somerville is paved, and eighty-two percent of the city is defined as a “hot spot,” or an area that has a heat index in the top 5% statewide. Stronger storms intensified by climate change are a threat there, too. Just a few decades from now, extreme storms in parts of Somerville could bring up to 10 feet of flooding. But there may be some relief in sight. Somerville residents are taking matters into their own hands. Living on Earth’s Sophia Pandelidis went to find out more.

[sfx dumpster and sledgehammer]

PANDELIDIS: It’s Sunday morning, and a ragtag group of neighbors has shown up to party.

[sfx sledgehammer]

PANDELIDIS: But not the way you might think. First off, they’re all wearing hard hats.

MEUNIER: And please make sure, if you're in this area, that you're wearing your equipment the whole time.

Living on Earth producer Sophia Pandelidis (second from right) gets the run-down of how depaving works. (Photo: Green and Open Somerville)

PANDELIDIS: This is a “depaving party.” About 20 volunteers are gathered in the fully paved backyard of a Somerville, Massachusetts home. And it’s their job to rip it up.

LIPSHULTZ: Swinging.

[sfx sledgehammer]

LIPSHULTZ: Wow, Oh my gosh.

PANDELIDIS: Armed with sledgehammers and wheelbarrows, the group works together to break up the asphalt and carry it to a dumpster in the driveway.

[sfx dumpster]

PANDELIDIS: The goal is to leave this yard pavement-free. These “depaving parties” have been happening since 2010 and are now run by Green and Open Somerville. Leigh Meunier is one of the leaders of the group’s “Depave the Way” initiative. Her wide, bright eyes make you want to listen to her. She says there’s more than one reason to ditch asphalt.

MEUNIER: One of the things I really love about depaving is—is that it is multipurpose.

Armed with sledgehammers and wheelbarrows, volunteers work together to break up the asphalt and remove it. (Photo: Green and Open Somerville)

PANDELIDIS: First, it helps neighborhoods adapt to climate change. Depaving can prevent flooding by giving stormwater a place to soak into the ground and lower temperatures by reducing the urban heat island effect. That could save lives, especially in environmental justice communities that face higher heat risks. But climate resilience isn’t the only benefit to depaving.

MEUNIER: Ideally, when you can get pavement out, it increases not just more space for water to go, but it increases opportunities for planting gardens, for planting trees, for yards, for kids to run around and play, park space, etc. It's like, amazing.

PANDELIDIS: Yards filled with native plants instead of asphalt can also be havens for pollinators and local wildlife.

Jack Briskie, the host of today’s depaving, has plans for that.

BRISKIE: I've watched far too much Home Improvement TV on building bee houses, actually.

PANDELIDIS: But Leigh’s favorite part of depaving is how it brings the community together in an active way.

Host Jack Briskie stands in the dumpster full of asphalt. Renting a dumpster can cost up to $700. (Photo: Green and Open Somerville)

MEUNIER: I want to get sweaty. I want my active energy, you know, to go towards something, and my creative energy to go towards something that's meaningful.

PANDELIDIS: One veteran depaver, Eduardo Rodriguez, is on a similar wavelength. He says there’s something cathartic about swinging that sledgehammer.

RODRIGUEZ: That first drop uh, just releases so much rage. Yeah, and uh, we have a lot to rage about right now.

PANDELIDIS: The “depaving” movement is not new. It got its start in Portland, Oregon, back in 2007, and has since spread across the United States and even Europe. Leigh says word is travelling fast here in Somerville.

MEUNIER: More people are biking, walking, taking transit, and have less need for cars. So, we have all these long driveways that fit like five cars, and everybody's moving in and saying, I don't need that anymore, you know.

PANDELIDIS: This season’s depaving schedule is already filling up.

Another Somerville driveway before depaving. (Photo: Green and Open Somerville)

MUENIER: We're now on track to do at least seven this year, if not more.

PANDELIDIS: Everyone who wants to depave should be able to, Leigh says. But keeping up with growing demand is tough for her small team. And while volunteers are free, depaving still has a price too steep for some: up to $700 to rent a dumpster.

[sfx dumpster]

PANDELIDIS: So Green and Open Somerville is partnering with local NGOs to offset those costs for low-income, environmental justice neighborhoods. Leigh dreams of a time when she’ll get to lead these parties every weekend. For now, though, it’s time to sit back and admire the day’s work.

MEUNIER: Depaving, to me is, like, one of those things too, where you can, in three hours, see the fruits of your labor.

These residents decided to plant a garden where their driveway used to be. (Photo: Green and Open Somerville)

PANDELIDIS: She’s right. At the end of the party, it’s incredibly satisfying to watch as the last chunks of pavement are carried away and we’re left with… well, an actual yard, though it’s barren for now. So, the group heads inside, muddy and tired, but proud. Their sandwiches will be well deserved.

[sfx sledge hammer]

PANDELIDIS: . For Living on Earth, I’m Sophia Pandelidis in Somerville, Massachusetts.

Related link:

Green and Open Somerville: “Depave the Way”

[MUSIC: Average White Band, “Pick Up The Pieces” on AWB, Atlantic Recording Corporation]

CURWOOD: Coming up – tips for choosing organic when it matters most. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Waverley Street Foundation, working to cultivate a healing planet with community-led programs for better food, healthy farmlands, and smarter building, energy, and businesses.

[MUSIC: Vision String Quartet, “Samba” on Spectrum, Parlophone Records Limited, a Warner Music Group Company]

The "Dirty Dozen" and "Clean Fifteen"

Strawberries are ranked number one on the Dirty Dozen list, indicating that they are on average the most contaminated from pesticides when bought conventionally. (Photo: Suzanne Schroeter, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Some human studies suggest that eating more organic food may reduce risk of cancer, and pesticide exposure is certainly not good for our health. But there are tradeoffs. Organic food has limited availability and can cost more. The good news is that not all conventionally grown fruits and veggies are loaded with high levels of pesticides. To help consumers make efficient choices in the produce aisle, every year the Environmental Working Group puts together two lists, the “Dirty Dozen” and the “Clean Fifteen.” Here to explain what these lists mean and how to use them during grocery trips is Alexis Temkin, a Senior Toxicologist at the Environmental Working Group. Welcome to Living on Earth, Dr. Temkin!

CURWOOD: So, the Dirty Dozen and the Clean Fifteen. How did the Environmental Working Group put these two lists together? What makes one food dirty and one food clean?

TEMKIN: Yeah, so this is part of a broad consumer guide that we use called the Shoppers Guide to Pesticides and Produce, and we actually look at around 46 different fruits and vegetables for pesticide residues. And these data come from federal agencies that are testing fruits and vegetables on store shelves for the presence of pesticides. And we essentially analyzed that data to look at which fruits and vegetables have the most pesticides, whether that's the number of pesticides found, the concentrations, the detection frequencies of different fruits and vegetables and the ones that come out on top are claim the Dirty Dozen, things like strawberries, spinach, kale, grapes and things that come out on the bottom as the least contaminated, the Clean Fifteen, things like avocados, sweet corn, pineapple and onions, those are the Clean Fifteen.

Before testing fruits and vegetables for pesticides, researchers will wash and prepare the sample in the way it is usually consumed. For example, bananas are peeled before testing. (Photo: Emilian Robert Vicol, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So how is this order determined? I mean, for example, I see that strawberries are ranked number one on the Dirty Dozen.

TEMKIN: We use, as I mentioned, data that's actually generated from the United States Department of Agriculture, primarily, as well as from the FDA. There's a program at the USDA called the Pesticide Data Program. We've developed a tool to rank fruits and vegetables based on the analysis of that data. So, it's using six different indicators of pesticide contamination. So we look at for each of these different commodities, you know, whether that's strawberries or apples or blueberries, we look at the percent of those samples that have detectable pesticides, the percent of samples that have two or more, because actually a lot of fruits and vegetables can have, in some cases, up to a dozen or so different pesticides detected, the average number of pesticides on a single sample, the average amount of pesticides found, the total number found on a single sample, and the total number found on the crop. So, there's a few different ways we analyze this, and then based on how you rank in each of those ultimately determines how you rank in the final sort of list of those 46, which we break up right into 12 and 15.

CURWOOD: I'm learning something here because I thought strawberries were at the top of the Dirty Dozen, because you just can't wash the pesticides off of strawberries.

TEMKIN: This is a great point, and I'm so glad you're bringing it up, because the way that the data are generated from the USDA actually involves a washing step before they test for pesticides. So, part of this program in terms of pesticide residue analysis from the USDA, is actually designed to try and mimic consumer exposure to some degree. So, fruits and vegetables are typically washed for some period of time, you know, akin to how somebody might do it at home. Fruits and vegetables that need to be peeled, like a banana or a citrus or something like that, are peeled before they're analyzed. So, you definitely don't get rid of all of your pesticide exposure just by washing. There's still a considerable amount of pesticide left over, although washing is something we definitely recommend to at least remove some possible pesticide residue.

The Environmental Working Group, who compiled these two lists, recommends choosing the organic option when buying foods on the Dirty Dozen list to avoid consuming large quantities of pesticides. (Photo: Harrison Keely, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

CURWOOD: Let's cut to the basic question here: why should people be concerned with pesticides in their diet, especially those of us who've been eating nonorganic produce our whole lives, maybe even today.

TEMKIN: Yeah, well so fruits and vegetables definitely offer an immense amount of health benefits. So, it's something that we always want to emphasize, that it's really important to continue eating fruits and vegetables, even of conventionally grown produce. You know, the reason we put out this guide is so that if you're shopping for items on the Dirty Dozen, if you're a strawberry lover, for instance, it might be worth considering buying those organic to reduce that pesticide exposure. And then this Clean Fifteen list are sort of low in pesticide residue, even through conventional. So, it's a way to sort of balance perhaps buying organic and buying conventional. Because, of course, that can be difficult, but some of the reasons you might wanna be concerned are that exposure to pesticides have been linked to a variety of health effects. There are a few neurotoxic pesticides that can be really important in terms of their impact on developing brains. Some mixtures of pesticides have also been associated with reproductive harm, like actual impacts on fertility, and in some cases, we've also seen pesticides associated with cancer risk. And really, the way that these pesticides are regulated are looking at them one at a time, but we know from looking at this data about pesticides on food, you know, there's about 250 different pesticides detected on food, so the way we're exposed are these mixtures of pesticides. And we sometimes know that when you're exposed to multiple pesticides, there can be different health effects at lower doses than if you were just exposed to one, which is how the regulatory agencies really regulate them.

CURWOOD: Understanding all this, what should people do? What should we do as consumers?

TEMKIN: I mean, I think it's understandable that this is a balancing act, and it is also how we live our lives, and that can be really hard to sort of balance all these different things and worry, how much am I exposed to? How concerned do I have to be? And I think that's exactly why this shoppers guide, or the Dirty Dozens, came into existence, was just to hopefully try and optimize that balance so that there's this beneficial experience of eating a lot of fruits and vegetables, which we know has been studied over and over again in the literature, and is extremely important, it can be really health protective. There are some studies that show sometimes, if you look at the health benefits on cardiovascular disease by eating fruits and vegetables, one study actually showed that, well, if most of your vegetable consumption comes from high residue foods that protective benefit gets a little bit weaker. So, we wanna sort of optimize how you get the benefits of both, and one way to do that is by reducing exposure to pesticides. And you could eat an organic diet all the time, but that's really just not doable for most people. I certainly can't even do that. So, we recommend buying organic options of items on the Dirty Dozen if they're things that you love to eat. You know, for instance, I personally don't love strawberries. I don't eat them all that often, but I do love other things on the Dirty Dozen that we try to buy organic, and then the Clean Fifteen are also really wonderful fruits and vegetables that just have low pesticide residues.

Onions are listed second on the list of the Clean Fifteen, with no more than three pesticides found on samples tested. (Photo: Mike Mozart, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Wait a minute, you're not into a strawberry on a hot June day that's just so sweet and dripping with the beginning of summer essence?

TEMKIN: That does sound wonderful, actually, when you put it that way, strawberries in season are a special, special treat.

CURWOOD: What about the money? Organic sometimes, but not always, costs more. Someone listening to us, thinking about that, you know, budget is a little tight. How far should they reach to include organic in that budget? Do you think?

TEMKIN: I think it's a hard question. I think that's really a personal decision. I would, I guess, prioritize, as I mentioned, eating fruits and vegetables first over processed foods, and then if the budget allows really shifting towards organic options on the Dirty Dozen, or really looking at just more of those conventional options on the Clean Fifteen, you know, but like avocados, kiwi, asparagus, mushrooms, sweet potatoes, carrots, I don't know, that sounds like a lovely stew.

CURWOOD: And what's your favorite on your list of the Clean Fifteen? What will you be cooking tonight, do you think?

TEMKIN: I will probably be cooking something with sweet potatoes, which are on the Clean Fifteen list, and mushrooms… And onions!

Less than 2% of avocados sampled had detectable pesticides, earning them the number one spot on the Clean Fifteen list. (Photo: Jack Kennard, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Okay, there you go. It'll smell good.

TEMKIN: Yes, exactly.

CURWOOD: Alexis Temkin is a senior toxicologist at the Environmental Working Group, the organization that publishes the Dirty Dozen and Clean Fifteen. They change it every year. Thank you so much for taking the time with us.

TEMKIN: Thank you so much for having me.

Related links:

- Environmental Working Group’s 2024 Shopping Guide to Pesticides in Produce: Read here

- Environmental Working Group’s 2024 Clean Fifteen List: Read here

- Frontiers | “Pesticides Potentially as Bad as Smoking for Increased Risk in Certain Cancers”

- CNN | “Toxic ‘Forever Chemicals’ Found in Pesticides Used on Food, in Homes and on Pets, Study Finds”

- CBS | “Pesticides Pose a Significant Risk in 20% of Fruits and Vegetables, Consumer Reports Finds”

[MUSIC: The Beatles, “Strawberry Fields Forever” on YouTube originally on Magical Mystery Tour, by John Lennon and Paul McCartney, Universal Music Group]

Shiitake Mushroom Harvest

The inoculated log behind Jenni’s compost bin. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

CURWOOD: Well, one great way to ensure you’re not getting a side of pesticides with your food is to grow it yourself. You can even grow your own organic mushrooms right in your backyard.

And Living on Earth Producer Jenni Doering joined me soon after she and Producer Aynsley O’Neill harvested the first crop of shiitake mushrooms from Jenni’s backyard. There were a few bumps along the way, she said…

DOERING: Well, we did successfully grow and harvest some mushrooms…

CURWOOD: Uh, wait a second, you don’t sound exactly certain here, Jenni.

DOERING: Well, okay, it all started out fine. I invited Aynsley over when I first noticed that they had sprouted up…

[OUTDOOR AMBI]

DOERING: So, it's back here behind my black plastic compost bin. Look at that.

O'NEILL: Whoa. Okay, those are, those are really big. I didn't realize they were that big.

DOERING: Yeah. I mean, like five inches across, maybe?

O'NEILL: Yeah like, like the palm of your hand.

CURWOOD: Uh, Jenni, if I’m seeing a shiitake mushroom in a grocery store, I don’t think it’s usually grown to that size.

DOERING: Yeah, there’s a chance we left it a little too long. I didn’t notice them until they were already that big, and they also were looking a little bit dried out…

[OUTDOOR AMBI]

DOERING: Now, some of this has a little bit of, like, brown on the gills. I think that might mean they're starting to get older, but we can still try these. I think we can still cook them up.

O'NEILL: Yeah, and I think we should, you know, definitely make sure to identify the mushrooms before we eat them anyway, just in case.

DOERING: Yeah, yeah, something else. Yeah, you know, like, you don't want, like, a death cap growing on this log, yeah. And then you, you're like, oh, dinner!

O'NEILL: Yeah, we'll head in and do some research.

CURWOOD: Right, well of course, you really have to be careful with identification when foraging mushrooms out and about, but I suppose you’d still want to be cautious with this backyard crop. I mean, these should be shiitakes, but—but what if something else snuck into that log?

Wild shiitakes growing on a log. (Photo: Ezonokuma, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

DOERING: Right, that’s the thought that snuck into my mind, I mean, a backyard isn’t a sterile environment. We gave those shiitakes a head start so they likely would have outcompeted anything else, but it’s always good to check, especially if you’re going to be cooking them up like we were!

CURWOOD: And, Jenni, what were your culinary plans here? I mean, there are a lot of different ways to prepare mushrooms, what were you thinking?

DOERING: Well, we didn’t want to complicate the flavor too much, so we stuck with a very simple recipe.

[KITCHEN AMBI]

DOERING: So, I think we can cook them up with some onion, green onion, salt, and pepper, and see how they taste.

O’NEILL: Delish! Let’s go!

DOERING: I'll do some chopping over here. So, bite sized pieces for the mushrooms, we're gonna dice the onion, add them to a pan with a little bit of oil, and sauté. Okay.

[CHOPPING SFX]

O'NEILL: Our ratios might be a little off. That's fine.

DOERING: Yeah.

O’NEILL: Onion, scallion, mushrooms, it's all tasty. So, you know. And part of our goal is to have the taste of the mushrooms shine through I think, so…

[SIZZLING SOUNDS]

CURWOOD: Mm mm, that does sound tasty.

DOERING: Oh yeah, there was just one problem though…

[KITCHEN AMBI]

[SAUTEEING SFX]

DOERING: Wait, were we supposed to, like, double-check and research these?

[SAUTEEING SFX]

CURWOOD: Oh, Jenni, say it ain’t so!

DOERING: That’s right, Steve, we got so distracted by cooking that we almost forgot to finish our research!

CURWOOD: That could have been real trouble…

DOERING: Yes, well, luckily, there aren’t too many poisonous mushrooms that look like shiitakes. But we weren’t taking any chances!

The harvested shiitakes. (Photo: Aynsley O’Neill)

CURWOOD: Okay, Detective Jenni. How did you do your sleuthing?

DOERING: So, we tried a few different avenues. First, we reached out to the customer service desk for the company where I got the starter kit.

[ROOM AMBI]

DOERING: All right, so Tony Lee from North Spore got back to me and said, I'm happy to help with the identification. So, they said, “can you provide pictures of the topside, underside, and habitat?”

O'NEILL: Oh, we have all of those.

DOERING: We've got all of that. So, I'm attaching these.

O'NEILL: I love picturing somebody sitting at their desk with a headset on with a big book of mycology next to them, ready to identify at any given moment.

DOERING: All right, moment of truth. Thanks for the inquiry. Based on the information provided, it looks like you have some shiitakes. With photos alone, though I can't provide 100% certainty, it's important for you to consult other credible sources…

CURWOOD: Hmm. That only sounds a little reassuring.

DOERING: Right, so after that, we did some online research on some mushroom identification sites, and we sent pictures to some amateur mycologist friends. And I’m happy to report that everyone came to the same conclusion!

[ROOM AMBI]

DOERING: So, a couple of people confirmed they do look like shitakes. So, what do you think? Do you feel safe trying these, Aynsley?

O’NEILL: Let's give them a go!

DOERING: Let's give them a go. So, I'm tasting this for the first time. Want to see if the seasoning is right. So, here we go.

O'NEILL: Hmm. It smells really good, is what I'll say.

DOERING: Yeah, that's nice. It's earthy, nice. I think I'm just gonna add a little more seasoning.

[PEPPER MILL SFX]

Shiitakes for sale at a market, with a very uniform size and shape. (Photo: Peachyeung316, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

O'NEILL: A pinch more salt.

DOERING: Okay.

O'NEILL: Let's dish it up.

DOERING: Yeah, so a little bit of scallion.

O'NEILL: Delicious. Fresh scallions, too. From the garden.

DOERING: Yes, straight from the garden. Bon appétit.

O'NEILL: Cheers

DOERING: Cheers

[CLINK SFX]

O'NEILL: Oh, that's good.

DOERING: Mm, hmm, this would be really good in a stir fry, or, like, in ramen.

O'NEILL: Oh, Yes!

DOERING: I could also use the rest in some pasta, like—

O'NEILL: For sure

DOERING: —Parmesan and some butter, you know, something simple.

O'NEILL: Or, you know, hibachi or barbecue, you know, some sort of grilling, things like that, super good, yum. Really nice, really cool. I mean, you're already a gardener, so you grow your own stuff all the time, but first crop of mushrooms. How's that?

DOERING: Yeah, this is exciting. This is, this is a step up, I guess, but it's also, it really wasn't that hard. There was just some setup. There was some drilling, and—I let that log sit there for a year, you know, like, it just hung out behind the compost.

O'NEILL: Yeah, you really set it and forget it, the way they say, you know.

DOERING: And we should be getting some more of these throughout the next few years. So, lots to look forward to.

O'NEILL: You'll have to bring some into the office.

DOERING: I think I will.

CURWOOD: I am in full agreement and glad you are still healthy. So, please bring some in for the whole crew to try next harvest!

DOERING: Copy that, Steve!

CURWOOD: That’s Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering, reporting on her mushroom adventures with LoE's Aynsley O’Neill.

Related links:

- Listen to LOE’s previous coverage of a backyard mushroom kit here

- Learn more about the process of growing mushrooms on a log

[MUSIC: Al Petteway and Amy White, “Riding the River” on Racing Hearts, Fairewood Studios]

CURWOOD: Just ahead, Scientists consider the notion of plant intelligence. That’s coming right up on Living on Earth. Stay with us!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the estate of Rosamund Stone Zander - celebrated painter, environmentalist, and author of The Art of Possibility – who inspired others to see the profound interconnectedness of all living things, and to act with courage and creativity on behalf of our planet. Support also comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green, and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[MUSIC: Vision String Quartet, “Willi’s Farewell” on Spectrum, Parlophone Records Limited, a Warner Music Group Company]

The Light Eaters

Zoë Schlanger’s book The Light Eaters: How The Unseen World of Plant Intelligence Offers a New Understanding of Life on Earth delves into topics like plant sensation, communication, sociality, and intelligence. (Photo: Courtesy of HarperCollins)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. A scientist who rappels down cliffs to hand-pollinate endangered plants. A vine that mimics the leaves of nearby species. Rice that crowds out strangers but leaves room for the roots of relatives. All of these are subjects of the book The Light Eaters, by Zoë Schlanger, who tackles big questions of plant intelligence, consciousness, and communication. Welcome to Living on Earth, Zoe!

SCHLANGER: It's so great to be here.

CURWOOD: So, early in your book you write, "I was regaining material intimacy with the natural world by looking at plants. It wasn't a way to ignore environmental catastrophe, it was a way to reattach myself to the stakes." So how can studying plants change our perspective of the climate emergency we're in right now?

Author Zoë Schlanger stands by a Moreton Bay fig tree at National Tropical Botanical Garden in Kauai, Hawaii. It can be humbling to remember that every molecule of glucose we’ve ever consumed was first created by a plant through photosynthesis. (Photo: Gloria Dickie)

SCHLANGER: So, I'm a climate reporter. And I came to this project out of feeling quite numb and fatigued, as many of your listeners probably also feel, about all of the bad news related to climate change. And I think the biggest takeaway for me of studying plants for the last several years was the incredible creativity that exists in biology and evolutionary trajectories, and the ways that plants make a living exactly where they're rooted in place. They find ways to thrive against all circumstances, despite not having brains, in incredibly cunning ways. And I think, as it relates to my own kind of muddled feelings and numbness around climate change, it really reminded me of the worth of trying to protect as many species as possible, because every single one of these is a remarkable feat of ingenuity from a biological standpoint. And it really helped me expand my mind beyond the few plants that we actually use in our human economies to just actually have this appreciation for all plant life. And it's very humbling to remember that we're also entirely dependent on them. You know, every molecule of glucose we've ever consumed was first made by a plant; it made it through photosynthesis, through sunlight, water, and air. So, it really rearranges one's sense of where you are in the so-called hierarchy of life and reminds you that life finds a way.

CURWOOD: So, as you point out, plants don't have brains. And yet, you've written a book about plant intelligence. Square that circle for me, please.

When an insect (or a toothpick) touches the hairs on a Venus Fly Trap’s mouth-like leaf, it provokes an electrical signal that triggers the leaf to close. (Image: Mnolf, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

SCHLANGER: Sure. I mean, this is the million-dollar question. Scientists are understanding now that plants are able to respond in remarkably dynamic ways to their environment and make good choices for their future. They're able to record information about the past and use it in their decision-making. They can sense their kin, they can communicate, all of these incredible things. And they do it all without a brain. And no one has answered the question yet of how all of this information is integrated in a plant body without centralized processing. But there's actually really good evolutionary theory for why a plant wouldn't produce a brain, but might be able to do remarkable things regardless. We evolved a brain in part because we had to move across long distances to gather food, to flee from threats, we needed something really compact and portable. Plants, on the other hand, had none of those particular constraints. They had other ones. They needed to be able to stay in one place, but also sense their environment, and also easily lose a limb or two when it called for it, without being damaged in some major way. So, you end up with this kind of decentralized, modular creature that somehow is able to still integrate information across its whole body, to make good choices about where to grow, and how to find food. So that is really this huge open question of how they integrate this information without a brain.

CURWOOD: At one point, you make a comparison to the brains that animals have and the—the number of neurons and everything in their brain versus what plants have for ways to sense what's going on around them.

The evening primrose will increase the sweetness of its nectar when it vibrates at the same frequency as a bee buzzing. (Photo: Steve Guttman NYC, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

SCHLANGER: Yeah. Well, it's important to mention that plants do not have neurons, there's no synapses, there's no nervous conduction in the literal sense that we think of with our own brain and our own bodies. But there is electricity moving through a plant body. And there's been plenty of work finding that certain activities in plants are mediated by electricity in the sense that a Venus flytrap, when it closes, it's because these little trigger hairs on the inside of its maw, its mouthlike leaf, have been flicked by a wriggling fly or whatever it's just caught. And each one of those little flicks is associated with a flash of electricity, an action potential. And that's what triggers the trap to close. So, there are somehow ways for this plant to experience the phenomena of touch and respond to it in kind. There's chemicals being exuded that the plant can emanate from one branch, and then another branch of it can absorb those chemicals and register them as information. So, there's no brain, there's no neurons. And yet there is this whole-body connectivity that we see in plants, which is quite remarkable.

CURWOOD: Let's go back to the 1970s, when an influential book called The Secret Life of Plants was published. What was the impact, do you think, of that book? And how did it shape your approach to writing this book?

SCHLANGER: The Secret Life of Plants absolutely haunted every single day of reporting on this book, because you can't talk to a botanist now who doesn't acknowledge the way that it tanked the field for a full generation. This book was incredibly influential. Never before had a work of botany broken onto the popular scene so powerfully. I mean, there was a feature film, Stevie Wonder wrote the soundtrack, it's a very good soundtrack. And this is where people began talking to their plants, or had the idea that plants enjoyed classical music more than rock and roll, all these pretty pseudoscientific ideas that were inside this book.

The book The Secret Life of Plants, published in 1973, popularized the idea that it is beneficial to talk to your plants, and that they prefer classical music to rock & roll. There is little evidence to support these ideas, but plants do respond to sounds, such as that of a bee buzzing or a caterpillar chewing. (Photo: Jordan González, Unsplash, Unsplash+ license)

CURWOOD: So wait - is that pseudoscientific, that there might be a response to us talking to our plants?

SCHLANGER: As far as I know, there's no reason a plant would respond to us talking. Although there's amazing work being done now in the world of phytoacoustics in terms of plants responding to sound. They certainly do, but more likely it's sound that's ecologically relevant to the evolutionary history of that plant. We've only been with plants for a mere few thousand years; plants have been evolving for millions and millions of years. So, it doesn't make a lot of sense for them to be responsive to our talking, although probably if you talk to your plants, it means you're a much better plant parent than you would be otherwise, and they probably love that.

CURWOOD: What about singing to them, or banging a drum, which would go back thousands, millions of years?

SCHLANGER: That would be an interesting thing to test out. I mean, what we do know is plants can respond to the sound of a caterpillar chewing, or a bee buzzing, and will make adjustments. Evening primrose will increase the sweetness of its nectar by three times, very quickly, when it starts to vibrate at the same frequency as a bee flying by or buzzing. Plants are very receptive to vibration. It's a physical stimulus. So, to them sound is pure vibration. So, who knows? I mean, there's probably a lot of sounds that plants are receptive to.

CURWOOD: And plants can feel pain, or at least they send out signals indicating that they've been pinched. Please describe the experiment that demonstrated that to you.

SCHLANGER: Yeah. Well, to be super clear, there's nothing to suggest they can experience pain in the way that we experience pain, as this like, displeasing sensation. But we do know that when a plant is injured, when it's, let's say, clipped, or bitten by a predator, or bent, that will produce a flurry of defensive chemicals to make itself either less palatable, make its leaves very bitter, or send out warnings to other plants in the area that there's an attack underway. Or at least those plants are able to pick up on those chemicals from that injured plant and recognize that they have to boost their own immune systems. So, certainly plants produce strong reactions to being hurt. And I think about this now every time I touch a houseplant. I was able to go to a—a lab in Wisconsin that is working with plant wounding experiments, and they've imbued these plants with these fluorescent green proteins from jellyfish. And those proteins are attached to calcium, which is typically seen as a precursor or like a signal that there's some electricity moving through a cell. And so, they handed me tweezers, we're in this dark microscope lab, and I pinch the plant with the tweezers, and suddenly there's this green eminence glowing from the place that I've pinched this plant, then it starts traveling down its vein system. And within about two minutes, the entirety of this little plant had received the signal of my pinch.

CURWOOD: Well, and in the course of this experiment, they had to encourage you to pinch harder.

SCHLANGER: It's true. Yes, I mean, think about it, you've just been told that plants can feel you touching them, and then you're expected to enthusiastically wound this plant. It felt like the vegetal version of the Milgram shock experiment. But then I remembered, of course, I eat salad, it's okay. Pinch the plant. And, and I did, and it was pretty spectacular to see.

CURWOOD: Speaking of eating salad, though, what does your work tell us about veganism? I mean, what moral superiority is there in just eating plants if plants are sentient beings as well?

SCHLANGER: I think it's a really interesting question, because we are animals that have to eat plants; there's no way around it. We need their sugars and proteins to keep ourselves alive. But it does start to bring into conversation this idea that, well, maybe every living thing is bent towards life and wants to keep living. And plants are no exception to that. I mean, it's interesting to try to have to hold in your mind that you, in order to survive, have to enact some violence on an organism that wants to keep living. And what does that mean? I mean, maybe it can introduce a sense of profound gratitude, or respect, or reciprocity with other creatures, and maybe that can shape how we treat them.

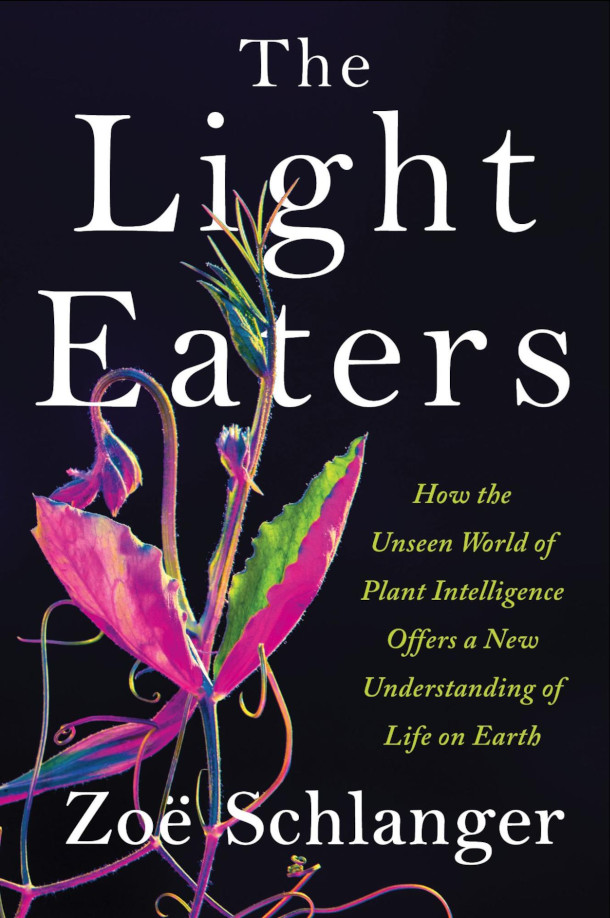

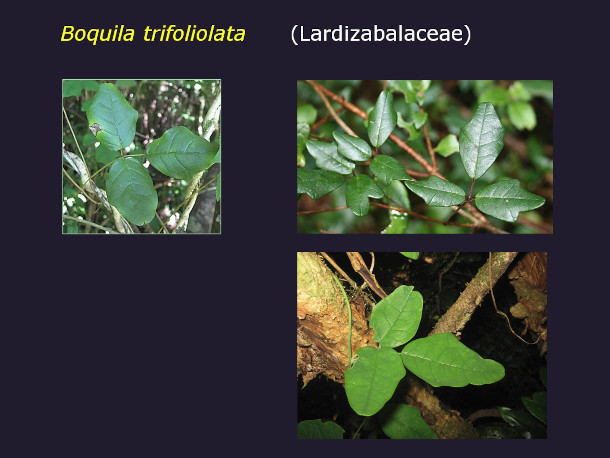

The vine boquila trifoliolata is known to mimic the leaf shape, texture, and color of nearby plants. These images show boquila leaves in their “original” state, not mimicking other plants. See below for images of boquila engaging in mimicry. (Photo: Courtesy of Ernesto Gianoli)

CURWOOD: So, to what extent does your work suggest that plants have consciousness?

SCHLANGER: Well, consciousness is this incredibly alluringly mushy concept. We don't know the mechanical basis for consciousness even in ourselves. We can't verify the consciousness of anyone but ourselves. It's something we feel, but it's extremely hard to pin down. And consciousness in some ways could be seen as simple as the capacity to take control of one's life and guide one's actions according to your best abilities, a sense of experiencing the world. And these are not outside of the realm of things that you can consider plants doing if you look at them a certain way, if you look at all of the science coming out, and holding in mind that there are realms of thought that believe that consciousness began with the very first cell, even. So we're deep in the area of theory here, and there's no easy answers, but it at least is an intriguing thought experiment that I think could really rustle us out of this kind of sense of human superiority in this realm.

CURWOOD: So, throughout your research process for this book, you traveled around the world and met a whole cast of, of characters. What was that like? And talk to me about one of your favorite characters from this.

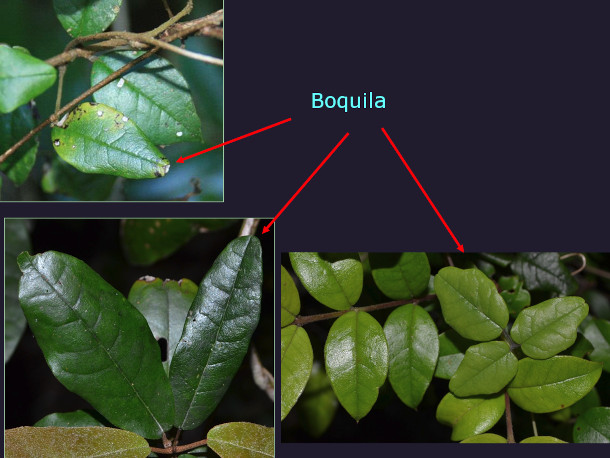

The leaves of boquila trifoliolata mimicking those of other plants. Scientists have differing theories about what enables this mimicry. Some believe that boquila is processing visual information about its neighbors. Botanist Ernesto Gianoli thinks boquila may be interacting with the microbiomes of other plants. (Photo: Courtesy of Ernesto Gianoli)

SCHLANGER: Botanists are some of the most wonderful scientists to talk to, in part because they have so much feeling for organisms that many of us maybe ignore, perhaps in favor of animals. I mean, I think about the fact that most of us can tell the difference between, like, a codfish and a toucan or something, but we can't tell the difference between wheat and rye, which are incredibly different species themselves. So, these are people who have profound connections to these much-ignored organisms. And their research is also mind-blowing. One of my favorite trips was to the southern rainforests of Chile, these temperate rainforests, kind of chilly, wet places. And there is a vine that grows in this rainforest called boquila trifoliolata. And this vine has, of course, always been there, at least for human memory. But it was just recently discovered to be quite literally a chameleon vine. It can spontaneously change the shape of its leaves, the color of its leaves, the vein pattern, the texture, to match the shape, to mimic the shape of anything it's growing beside. This plant can mimic up to four different species at the same time, with different parts of its vine structure. And no one knows how this is possible. So, I spent several days with the team of Ernesto Gianoli, a researcher who's studying this plant, and the vine has provoked this controversy over whether or not plants could possibly see. There are a camp of botanists who say, well, it's mimicking, spontaneously mimicking other plants--that must be a form of visual acuity, that they're taking visual information and processing it and producing this perfect mimic. But of course, plants don't have brains. So, where would they be transposing that visual information into an image in the way we think of it? But plants do have a ton of photoreceptors on their leaves, more than we have in our eyes, more different types of photoreceptors. So, there's some weight behind that argument. And then, the botanist himself who I was spending time with thought it was something far more sci-fi, that this plant was actually just receptive to the microbiomes of other plants, that the shape of plants is not determined by the plant itself, but rather by sort of third-party organisms. I mean, we talk a lot about the human microbiome and all these other creatures that live on and inside of us that dictate certain things about our own behaviors, let's say our mood, or our, our gut health. And he thought, well, maybe it's some kind of microbial takeover in that way. And this vine was just more receptive to that of other species.

Tomato plants can sense the particular species of caterpillar that is chewing on them, then emit chemical signals to attract a wasp that parasitizes that caterpillar. (Photo: Toshiyuki IMAI, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, if you wouldn't mind, if you could open your book to page 183? So, you're talking to the scientist Gianoli, and if you could pick up with that line, "We sit down on a log."

SCHLANGER: "We sit down on a log covered in pink and orange slime molds. Gianoli talks about the fact that termites were recently discovered to have microbes in their guts that make it possible for them to digest the chemicals in wood. In other words, the most signature behavior of termites--wood eating--is made possible by entirely different organisms living within them. The termite's gut microbes, in turn, are able to function thanks to yet smaller microbes that live within them. The presence of these animals-inside-animals predates the evolution of the termite itself--some termite ancestor likely acquired them by eating dead plant material where microbes were living. From there, both evolved together into the versions of each that exists today. One species of Australian termite is known to have a protist in its gut that, in turn, carries around four types of bacteria of its own. So many cascading individuals make a termite possible. 'They're independent, they're from different families, it's crazy,' Gianoli said. Over and over, the thrust of these new discoveries points in the same direction: a termite is never just a termite. The same is clearly true for every organism."

CURWOOD: Zoë, this theme of organisms being not just individuals, but a part of a larger ecosystem, this comes up a lot in your book. Tell me more about that.

SCHLANGER: Well, very quickly into researching this book, which is very firmly about plants, I realized it's really hard to tell where a plant starts and where a plant ends, because a plant is so hooked into and influenced by so many other organisms. I mean, fungi, for example, are entwined in the roots of virtually every single plant grown in the wild. And they're so a part of plants that some have posited that roots first evolved simply to house fungi. And they're interacting with microbes and viruses and molds, any number of other organisms all the time. It really is shaking the core of the idea of a biological individual. I mean, ourselves are not biological individuals—something like half of our cells belong to other organisms, have foreign DNA. And they may well be influencing things we think of as wholly the domain of our own bodies, things like our health, things like our mental state. We are not just one creature; we are highly dependent on and enmeshed with so many others.

CURWOOD: So, what were some of the most surprising things, beyond the things we've already talked about, that you learned when you were researching this book?

Zoë Schlanger is a reporter at The Atlantic and the recipient of a 2017 reporting award from the National Association of Science Writers. (Photo: Heather Sten)

SCHLANGER: I loved learning about the ways that plants can manipulate other creatures, even animals. They are able to kind of take the reins of a lot of other organisms. Plants have this entirely separate sense that we have none of, essentially, that is chemical synthesis. They are able to produce chemicals in their bodies that they then let out through pores on their leaves that infiltrate the bodies of others and make them do things. And so one example of this is the humble tomato plant. The tomato plant is able to sample the saliva of a caterpillar chewing on it, and from there, make a chemical that will summon the exact predatory wasp that will want to come inject its eggs into this caterpillar, and the eggs will then hatch, and the larvae will eat the caterpillar from inside out and glue its little white cocoons to the outside of this husk of a caterpillar. And this is how this tomato plant attempts to defend itself from the hungry mouths of a million caterpillars. It's really remarkable when you think about a plant manipulating an animal, it really turns a lot of ideas upside-down.

CURWOOD: So, what does studying plants tell us? What's the message?

SCHLANGER: Well, I can only say what learning all of this has done for me. And at a very simple level, these findings, these scientific developments around plant behavior, produce this immense feeling of awe, at least in me. And I know Rachel Carson wrote about this a bit towards the end of her life, and many people have studied this, that the experience of awe leads directly towards respect and sort of away from negligent behavior or away from indiscriminate destruction. And injecting ourselves with a big dose of awe could only do good things both for addressing climate change and just for being animals in this world.

CURWOOD: Zoë Schlanger's book is called The Light Eaters. Zoë, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

SCHLANGER: It's been wonderful talking with you. Thank you.

Related links:

- Find a copy of The Light Eaters (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

- Learn more about author Zoë Schlanger

- Zoë Schlanger’s profile at The Atlantic

- New York Times | “Are Plants Intelligent? If So, What Does That Mean for Your Salad?”

[MUSIC: Al Petteway and Amy White, “Riding the River” on Racing Hearts, Fairewood Studios]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Jenni Doering, Daniela Faree-ah, Swayam Gagneja, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Ashanti Mclean, Nana Mohammed, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, Bella Smith, Melba Torres, and El Wilson. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at loe.org, Apple Podcasts and YouTube Music, and like us please, on our Facebook page, Living on Earth. Find us on Instagram at living on earth radio, and we always welcome your feedback at comments at loe.org. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth