The Book of Delights

Air Date: Week of February 28, 2020

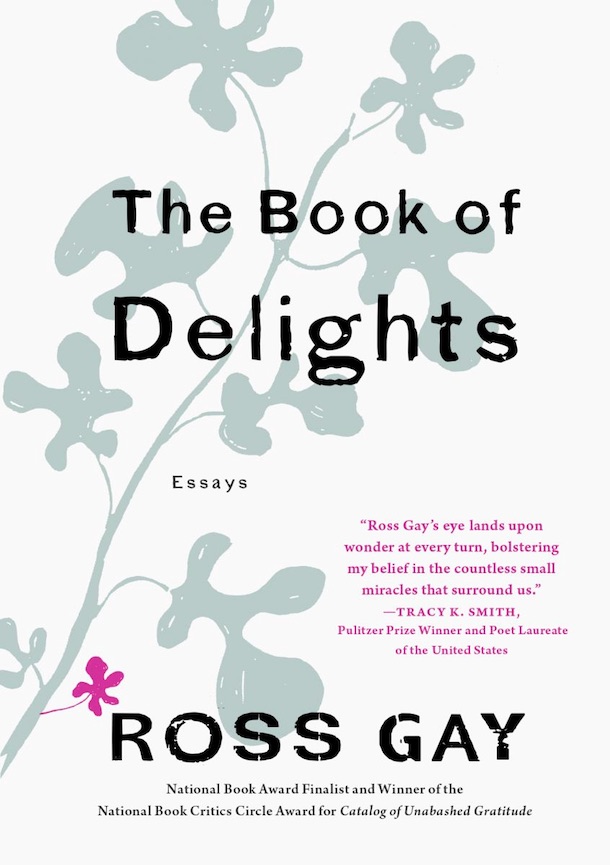

The Book of Delights is the first nonfiction book from poet Ross Gay, who dedicated a year to writing daily essays about the things that delight him. (Photo: Courtesy of Ross Gay)

For a year, poet Ross Gay took a moment almost every day to write about something that delighted him. He has compiled the essays into his most recent volume, The Book of Delights. Ross Gay joins Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb to discuss the power of finding delight in unexpected ways.

Transcript

CURWOOD: In an endangered world, gratitude and appreciation are difficult to balance with practical and existential fears. So to push back against fear, doubt, and gloom, poet Ross Gay took a moment almost every day for a year to write about something that delighted him and has published these observations in his latest volume, The Book of Delights. In this exercise, he found joy in everything from bumblebees to folding shirts at the laundromat and noticed beauty he had never seen before. Ross Gay spoke with Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb.

BASCOMB: So why write a book about delights? What inspired you to take on this project?

GAY: I was just in the middle of a, like a very pleasant walk. I was having a nice, delightful moment. And I thought, oh, how neat, it would, you know, just like, I could write about this. And then I thought, kind of quickly, oh, you know, it'd be interesting to write a book about something that delighted me every day for a year. And that's kind of how the idea for the project arrived.

BASCOMB: Mm-hmm. And you had a few rules of engagement for your project for writing about delight. Can you tell us about those?

GAY: Yeah, I was, I kind of wanted to write it every day. I didn't exactly get to that. But you know, pretty close. And I wanted to write the sort of quickly. And I wanted to write them by hand.

BASCOMB: You know, I wonder if that you know, leads you to a place where you're looking for something delightful where, you know, you're looking for something to be grateful for, in a sense.

GAY: To me that's one of the wonderful things about the exercise, or the practice was that I sort of realized that oh, I'm constantly in the midst of things that delight me that I have not yet realized delight me. And I haven't articulated them as delighting me, and I haven't shared them as delighting me. And then suddenly being, having the experience of being delighted more often, because now you recognize, oh, that's something that, that delights me. It's, it's really lovely. It's a really lovely thing.

BASCOMB: Can you give us an example of something that you didn't realize was delightful until you tried to put a word to it?

GAY: I'm delighted, by the way, that when people in a classroom, I'm often delighted by things in the classroom, if someone is reading, if we're reading in a circle, someone's going to read, and they're going to pass it along. I'm delighted, I mean, I love it. The pause between the sort of handing off from I'm reading and then the next person is going to read there's this sort of incredibly tender negotiation about how long should I wait and while you're done until I start, you know, these things like on and on, I love that thing. I love that thing.

BASCOMB: Now you find a lot of delight in the natural world. You have an essay in here about literally stopping to smell the flowers. There's, there are other essays about hummingbirds and praying mantis, fireflies, you talk a lot about your garden. To what extent do you think anyone can find delight in nature if they take the time to look?

GAY: When you look very closely, you know, the experience that I have often in a garden is looking very closely at a flower, or a plant, or something like that. And looking so closely that I realize, oh, I've never seen this before. You know, something that I see every day that it's in bloom or every day that it's making its fruit, something that I'm totally familiar with. When I slow down, which the garden encourages me to do, and I look in a different, slower way, kind of intentional way, I realize, whoa, I've never seen this before. And when I had that experience of whoa, I've never seen this before. I do have that experience, which I think is a lucky experience to be like, whoa, I've never seen anything before.

BASCOMB: To what degree do you think taking the time to appreciate the delights of nature can maybe make us better stewards of our environment?

GAY: I think basically what we do is, we care for what we love. You know, I think it's basically we care for what we love. And I think so often we, I think if we have the opportunity to articulate what it is that we love, then we are more likely then to tend to it and to care for it. So I do feel, I feel like it's absolutely part of the way that we are proper stewards of the land and we are properly entangled with the land and understand our entanglement with the land.

Ross Gay is an award-winning poet and the author of The Book of Delights. (Photo: Ross Gay)

BASCOMB: You also find delight in things that on the surface are not joyful at all. Things like being detained at the airport for extra security, a little pat down, and even enduring racism in your everyday life. How do you do that?

GAY: You know, the way that, if I think that, you know, something that I think is kind of interesting about this book is that it's a, it's sort of trying to like, you know, be a kind of adult book which is able to, or tries to practices articulating delight, articulating that which I love. And while at the same time articulating and understanding that the light does not exist, or the light exists often shoulder to shoulder with the brutal and what is not delightful, basically. So, yeah, a lot of these essays, you'll find that right next to something horrible is something, something not horrible or something delightful. And that's like one of them, to me, one of the interesting tensions of the book, is that sort of what feels to me like a grown understanding that, that many things are true at once, you know?

BASCOMB: Hmm. So maybe it's a delight in relief. Like you can't appreciate the delight of these things unless you've also known the painful aspects of life or the more difficult ones

GAY: Yeah, it's sort of like the light implies its absence you know? We know a delightful thing in part because we know an undelightful thing.

BASCOMB: Yeah, yeah, exactly. And so many of the delights that you're right about here are about intimacy, you know, those nicknames that your loved ones have for you or, or just these really passing interactions with strangers. You know the steward on the plane giving you a little arm pat, you know? Do you think that delightful moments like that are, are intimate by nature? I mean, there's the intimate relationship that you have with that bee in the flower but also with people.

GAY: Among my favorite experiences in this life are when people you know, someone sees a beautiful bird and they are looking at it and they see you and they point to it. Or there's a flower on a bush and someone is just sort of in it and says 'come on, you gotta smell this.' That thing which I think is like, I mean, I think it's one of our truest qualities, which is to share what we find beautiful. It's sharing, and I think sharing is a kind of, I haven't thought of it quite like this until you said it, but I think sharing itself is a kind of intimacy or, or probably, it suggests the possibility of intimacy.

BASCOMB: Do you have a copy of the book with you?

GAY: I do.

BASCOMB: Great. Would you mind reading a passage for us? I'm thinking of an essay called Black Bumblebees. It starts on page 262.

GAY: Yeah. Black Bumblebees. There is a kind of flowering bush, new to me, that I've been studying on my walks in Marfa. On that bush, whose blooms exude a curtain of syrupy fragrance, a beckoning of it, there are always a few thumb-size all-black bumblebees. Their wings appear when the light hits them right, metallic blue-green. I have never seen anything so beautiful. Everything about them- their purr, their wobbly veering from bloom to bloom- is the same as their cousins, the tiger-striped variety that shows up in droves when the cup plants in my garden are in bloom, making the back corner of my yard sound like a Harley convention. I wonder how I can encourage these beauties? These bees (though perhaps this observation is more about these flowers), mostly forego the sheer summer dresses, the pouty orifices of the blooms- though occasionally they dip in just enough to shiver the camisole- and instead land briefly on the outside of the flower, lumbering toward the juncture of or seen between the bloom and stem, where I imagine the nectar or pollen has dribbled or drifted. They then spin their legs into the base of the flower, shimmy some, swirl their abdomens for good measure and exhaling haul their furry bodies, gold-flecked, to the next bloom for more. I remembered, watching these bees, that among the delights of childhood was finding a patch of honeysuckle, sometimes with our noses and feasting on the nectar by plucking the flower from the vine, sliding the stamen free of the bloom, careful not to break it and sucking the faint sweetness dry. We would stay like that, licking flowers, sometimes for a half-hour. I'm pretty sure it was Joey Burns, at the time my best friend in the world, evidenced by the number of times we punch each other in the face, who introduced me when I was about six to the joys of honeysuckle plunder, for which I'd like to thank him. Though I do not thank him for the time he peed on me. And I do not want to praise myself too much. But I do consider it an innovation in honeysuckle when one time inspecting the flower I realized I might, without risking snapping the stamen, pluck the tiny bulbous stopper on the blooms bottom to tap the honey, as it were, in a kind of florid anilingus look into all the world. You're blowing the world's teeniest cornet. If only they knew.

CURWOOD: Ross Gay, reading from his volume, The Book of Delights. He spoke with Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb.

Links

All things Ross Gay at his website

Ross Gay giving a reading of an essay from The Book of Delights, ‘The Marfa Lights’

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth