February 28, 2020

Air Date: February 28, 2020

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Food and Drug Admin. Disputes BPA Health Risks

View the page for this story

The chemical BPA, an endocrine disruptor, is widely used in food packaging. Environmental Health News published a reported series showing that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has stacked the deck against findings from independent scientists that link BPA to harmful human health effects, ranging from birth defects to cancer. Science journalist Lynne Peeples joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss this investigation and why even BPA alternatives may also not be safe. (12:23)

Elizabeth Warren’s Climate Plan

/ Jenni DoeringView the page for this story

From healthcare to climate change, Elizabeth Warren has a plan for that. Living On Earth’s Jenni Doering reports on Elizabeth Warren’s $11 trillion climate platform, including plans for a Green New Deal, environmental justice, and ocean health, as voters weigh in on climate change as an election priority. (08:08)

Investors Eye Climate Risk

View the page for this story

BlackRock, with $7 trillion under management, is warning investors that climate change poses a major risk to portfolios and the economy. Mindy Lubber, CEO of sustainable investment group Ceres, discusses with Host Steve Curwood the BlackRock statement and why climate risk should be disclosed and mitigated just like any other risk. (08:31)

‘Parasite’ As Climate Fiction

View the page for this story

‘Parasite’, director Bong Joon-ho’s Oscar-winning film, examines the disproportionate impacts that climate change has on the rich and the poor. Ben Goldfarb a science writer with “The Last Word on Nothing”, explores how climate disruption plays in the plot of ‘Parasite’, and discusses how climate change and inequality manifest in the real world. (03:43)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week's Beyond the Headlines, Environmental Health News editor Peter Dykstra joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss the growing plastic industry in fracking country and the indigenous blockade of a major pipeline project in Canada. And from the history books, back in 1998 President Clinton signed a bill declaring Lake Champlain a Great Lake, for a moment anyway. (04:13)

The Book of Delights

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

For a year, poet Ross Gay took a moment almost every day to write about something that delighted him. He has compiled the essays into his most recent volume, The Book of Delights. Ross Gay joins Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb to discuss the power of finding delight in unexpected ways. (09:40)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Ross Gay, Mindy Lubber, Lynne Peeples

REPORTERS: Bobby Bascomb, Jenni Doering, Peter Dykstra, Ben Goldfarb

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

If Democrat Elizabeth Warren wins the White House she has a strategic plan to protect the climate.

WARREN: The first thing I want to do in Washington is passing my anti-corruption bill so that we can start making the changes we need to make on climate and the second is the filibuster. If you're not willing to roll back the filibuster, then you're giving the fossil fuel industry a veto.

CURWOOD: Also, scientists charge the federal government is cooking the science on dangerous chemicals.

PEEPLES: Academics have been doing these studies, that have found that just small doses of endocrine disruptors such as BPA, can cause harm. Meanwhile, the FDA still claims that BPA, at the doses at which we're exposed, does not pose any real health concerns.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Food and Drug Admin. Disputes BPA Health Risks

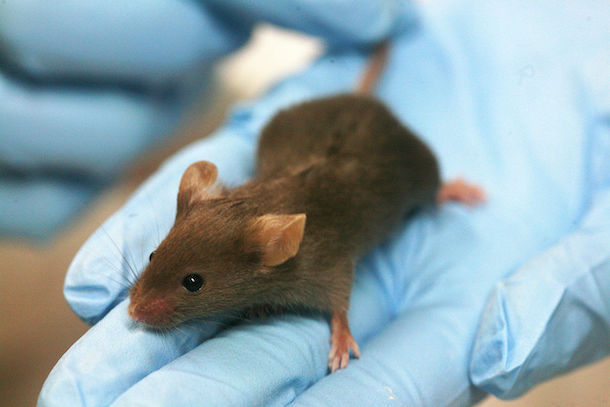

Bisphenol-A is an estrogen mimicker, and frequently found in plastics such as disposable water bottles, metal food cans, and even baby bottles. (Photo: Quinn Dombrowski, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Many synthetic chemicals today can pose health risks by mimicking those in our body’s endocrine systems, such as neurotransmitters, immune factors, and hormones including estrogen. More than ninety percent of us have been exposed to Bisphenol-A, or BPA, an estrogen mimic that is widely used in plastic products like food containers and even baby bottles. Environmental Health News launched a four-part investigative report called “Exposed”, which shows that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has stacked the deck against findings from independent scientists that link BPA to harmful human health effects, ranging from birth defects to cancer. Lynne Peeples reported the series and she joins us now from Seattle. Lynne, welcome to Living on Earth!

PEEPLES: Thanks so much for having me on.

CURWOOD: Well, give us a brief synopsis of what you did in this series of stories for Environmental Health News.

PEEPLES: Sure. So, kind of the driver here is this ongoing rift between academic scientists and federal and industry scientists. For many years, academics have been doing these studies, thousands now that they've published, that have found that just small doses of endocrine disruptors such as BPA, can cause harm. Meanwhile, the FDA still claims that BPA, at the doses at which we're exposed, does not pose any real health concerns. So there's been this conflict that's been ongoing. And this great idea came along, aptly named Clarity, which stands for Consortium Linking Academic and Regulatory Insights on BPA Toxicity. So this multi-million dollar project, co-led by the FDA, was launched and it is ongoing. But over the last few years, academic scientists and the government have published their data. Looking at the same set of rats and looking in their own ways at whether or not BPA has a health effect. Historically, the government has been evaluating BPA and other endocrine disruptors, looking for more kind of obvious effects or certain things that can really be easily measured, whereas academic scientists tend to look for perhaps more subtle effects, as well as effects at lower doses than the government has traditionally looked at.

CURWOOD: People listening to us may be scratching their heads a bit because it's not intuitive that tiny dosages can be toxic, even perhaps more toxic than larger ones. How does that work?

PEEPLES: Really, the idea is if you think about hormones in the human body, our bodies have been tuned to react to the tiniest of doses of hormones. The equivalent of just one drop of water in 20 Olympic sized swimming pools is enough to send instructions that can impact our growth, our metabolism, reproduction and other functions of the body. And as we've discovered, endocrine disruptors can act at the same minuscule levels in the body. So for academic scientists, it really comes as no surprise that these chemicals act in much the same way as hormones at tiny, tiny levels. And the issue here is historical, toxicologists have evaluated these chemicals with this assumption of "the dose makes the poison". So in other words, higher doses, as we've talked about, you know, cause more harm. Because of that assumption, the way that we've generally tested the chemicals is starting to expose lab animals to extremely high doses of the chemical, and then kind of ratcheting that down to a point at which they don't see effects and then from there, making a conservative estimate to drop that to a lower level. But if there are health effects that even lower doses we totally missed that. So that's where the academic scientists have been approaching the question differently and testing at some of these much lower levels.

CURWOOD: And Lynne, remind us what BPA, what Bisphenol-A is, and where it's most often found.

PEEPLES: BPA was actually discovered back in the 1930s, by a British medical researcher who found that it could mimic the activity of estrogen. So this goes way back, it was being considered for use as a hormone replacement. Instead, it found its way into plastics. You'd find it in the protective coating of cans, in some of your reusable plastic bottles, thermal paper receipts, as well as dental sealants. It's pretty widespread out there. You wouldn't necessarily have guessed that, given the pushback over the years against BPA, as you might notice a lot of BPA-free products out there on the market. And that's also worth noting that many of these BPA-free products also contain replacement chemicals that are equally harmful, if not more so, according to some studies. There's a lot of chemicals out there, we may not even know them all. And that's also kind of a fundamental issue here because the FDA, in facing this decision about how to regulate BPA, has the potential of opening this Pandora's Box. There are all these other chemicals out there on the market, chemicals that might be coming onto the market. And if, if BPA is identified as an endocrine disrupter, there's a whole lot of others that might be in line for the same kind of conclusion.

Bisphenol-A found in many plastic containers and water bottles is known to be harmful, but the substitute Bisphenol-S could be just as bad. (Photo: MMarsolais, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: 90% of us in the U.S. have been exposed to BPA at meaningful levels in our bodies. What are some of the health effects that research may ultimately show are linked to this exposure to BPA?

PEEPLES: A lot of it is related to our hormone systems. And when you think about it, our endocrine system drives a whole lot of functions in our body, but studies are suggesting that exposures may increase the risk of cancer, of diabetes, infertility. A really scary thought is that some of these studies are pointing to the derailment of the normal development of a child's brain. So, it's a wide range of potential effects. And scientists are continuing to publish more and more of these studies and looking at new different endpoints, some of which are a little more difficult to measure.

CURWOOD: So, the academic scientists are at odds with the Food and Drug Administration. And I guess industry scientists when it comes to testing the health effects of BPA and similar chemicals. How accurate would you say that is? And what weight to the concerns of industry put on the FDA's reaction?

PEEPLES: If you look back at the previous risk assessments that the FDA has done for BPA, those assessments really rely primarily on industry-funded studies. So industry appears to have had a loud say in how we deem BPA's safety. As one example, the FDA's 2014 risk assessment of the 36 studies that they had identified as related to neurological endpoints of BPA, the FDA chose just one to include in their risk assessment. And that study was funded by industry. And independently, there was a 2006 analysis that just looked at industry-funded studies. And they found that 11 out of 11 of them had deemed that BPA had no significant action on the human body. And then, meanwhile, there were 109 of 119 studies that had no industry funding that did find effects of BPA.

CURWOOD: So, the initial hope here was that Clarity, this consortium, would reconcile the ongoing clash between the FDA and academic scientists, but it sounds like in some respects, it's heightened the tensions here, it's heightened awareness of the conflict here. How accurate is that?

PEEPLES: I would say that's pretty accurate. The academics went into this process, seemingly mostly optimistic that this really could change the playing field and change the game. And just one thing after another seemed to go down that really led them to be pretty skeptical of how this will turn out. The final integrated report is still being pulled together. So, time will tell on that. But based on my interviews and hundreds of emails obtained via FOIA, it seemed that between the study design, the data analysis approaches, and the framing and interpretations that the FDA is made of the data thus far, that there were a lot of ways in which Clarity actually has clouded the picture of BPA.

The CLARITY-BPA program was founded as a way to resolve the differences that academic scientists and government and industry-funded scientists would conclude when they would test the effects of BPA. (Photo: Rama, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Tell me, to what extent in your view, is there bad science involved here? Things like dirty data, and biased data interpretation?

PEEPLES: There's no one smoking gun. Looking at all the data and all the evidence that I accumulated over the course of the year, there were some definite examples of ways in which the study design, the implementation, the analysis, and the presentation of the data thus far could have potentially diminished and maybe even totally hidden some of the true effects of the chemical. Now, none of these were absolutely blatant issues with the study, but they all sort of accumulated to raise a red flag. For example, some of the academic scientists I spoke with received what they say were, you know, too few animals to really have the statistical power to detect differences between their control and test animals. There was the FDA's chosen route of exposure for the animals to BPA, which as the scientists explained to me, could actually raise hormone levels due to the stress that that route of exposure caused so that could definitely diminish any obvious differences in health effects. There is some issue of potential contamination in the study. There were also concerns about the type of rat used, which previous studies had shown were insensitive to BPA. So taking all this together, there's definitely a reason why the academics remain concerned about this Clarity study really unveiling the truth behind the safety of BPA.

CURWOOD: You said that you obtained hundreds of emails. To what extent did any of those emails suggest an effort to ignore evidence of harm?

PEEPLES: So, a lot of these emails really underscored not only a rift between the FDA scientists and academic scientists but even within the government itself. So, I had a lot of emails from the National Institutes of Health. And some comments there reflecting on the FDA and its behavior with the study really struck a chord. For example, in February of 2018. This was when the FDA had completed its portion of the Clarity study, and they released a draft report, along with a press release that declared BPA safe. And NIH scientists that were involved responded amongst themselves, saying things like that the FDA officials had drafted a quote, "a statement to reiterate their current policy stance on the safety of BPA". So, there was a lot of frustration and distrust that came through on those emails. And there was also agreement before the study that there would be no public statements made until all the data was in and until that final report was put together.

Lynne Peeples is a freelance science journalist who reported the ‘Exposed’ series for Environmental Health News. (Photo: Lynne Peeples)

CURWOOD: So, the FDA went ahead and issued its statement saying BPA is fine, folks, don't worry. When in fact, the original deal, as you understand it, nothing was to be said until everything was done.

PEEPLES: Exactly. Right.

CURWOOD: How big a deal is this for public health? I've heard some say, and perhaps this is an exaggeration, that by not paying attention to the endocrine-disrupting, the hormone-disrupting effects of chemicals, it's like we're back in the stage when we didn't wash our hands to prevent the spread of infectious disease.

PEEPLES: Yeah. I mean, when you think about just how many chemicals are out there that have this potential impact of scrambling our hormones. It does frighten those scientists that I've spoken with that have a lot of expertise in this area that knowing that just a tiny quantity could have potentially profound impacts on the body. You know, where do we go from there?

CURWOOD: Lynne Peeples is an investigative reporter with Environmental Health News. Lynne, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

PEEPLES: Thanks so much for having me.

CURWOOD: And there's more on the story at the Living on Earth website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Environmental Health News | “Exposed: How Willful Blindness Keeps BPA on Shelves and Contaminating Our Bodies”

- Lynne Peeples’ website

[MUSIC: Eric Tingstad, “Key West” on Electric Spirit, by Eric Tingstad, Cheshire Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up –the investment world is warning about climate risk. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Eric Tingstad, “The Train of Thought” on Electric Spirit, by Eric Tingstad, Cheshire Records]

Elizabeth Warren’s Climate Plan

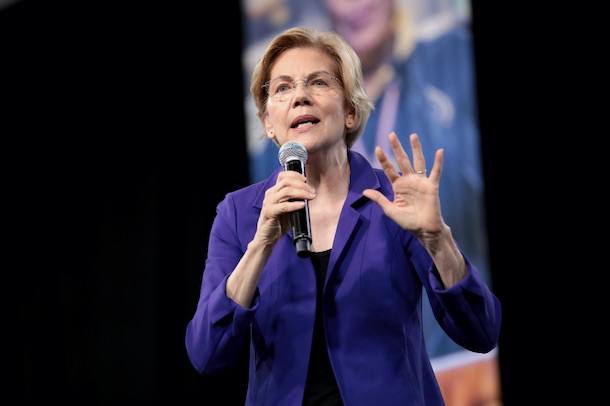

Elizabeth Warren updated her climate plan by incorporating aspects of the plan espoused by Jay Inslee, another of the Democratic presidential candidates, who ran on a platform of climate action. (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Democratic presidential hopeful Elizabeth Warren has an 11 trillion dollar strategic plan for tackling climate change. But time is running out for the Massachusetts Senator to capture delegates in the 2020 primary season. Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering details Senator Warren's Green New Deal.

[CHEERS]

WARREN: I got a plan for that!

[CHEERS]

DOERING: Elizabeth Warren’s campaign has been built on that mantra.

And one of her boldest, though hardly the most expensive, is her $11 trillion plan for addressing climate change. Here she is at CNN’s town hall on the climate crisis in September 2019.

WARREN: Climate change is real, it is manmade, and we are running out of runway to be able to fix this problem. We need all hands on deck on this one.

DOERING: “All hands on deck” means her Green New Deal for rapidly decarbonizing the US economy. At the heart of Senator Warren’s version is a pledge to reach one hundred percent clean, renewable, and zero-emission electricity by 2035.

She’s also calling for a “Blue New Deal”, to revitalize fisheries, green ports, and expand marine protected areas. And Elizabeth Warren says that her Green New Deal presents an opportunity to address and end the long, devastating legacy of environmental racism. Here she is at the Democratic debate in Nevada on February 19th.

WARREN: I want to make sure that the question of environmental justice gets more than a glancing blow in this debate, because, for generations now in this country, toxic waste dumps, polluting factories, have been located in or near communities of color over and over and over. And the consequences are felt in the health of young African American babies, felt in the health of seniors, people with compromised immune systems. It's also felt economically. Who wants to move into an area where the air smells bad or you can't drink the water? I have a commitment of a trillion dollars to repair the damage that this nation has permitted to inflict on communities of color for generations now.

DOERING: Among the presidential candidates, Senator Warren is one of the most vocal about environmental justice, and in November of 2019, she spoke about addressing longstanding injustice at the first-ever presidential forum on environmental justice.

And of course, she has a plan for that.

Elizabeth Warren speaking in 2019 at the National Forum on Wages and Working People in Las Vegas, Nevada. (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

WARREN: So, we will have a Council on Environmental Justice. And in my first hundred days, we will bring together the groups that have been trying to cope with environmental justice for generation after generation and say, Let’s lay out a plan for how to spend that money. Let’s layout a plan for how to lift up the communities that have been left behind. Let’s make a plan together for big structural change.

DOERING: All the Democratic presidential candidates currently serving in Congress are co-sponsoring the Green New Deal resolution introduced to the House and Senate. Elizabeth Warren’s version of a Green New Deal incorporates the plan put forth by Washington Governor Jay Inslee, a Democrat who ran for president on a climate-centric platform before dropping out of the race in August 2019. Although Senator Warren’s plan has a hefty $11 trillion price tag of both public and private financing, she says it promises to give a major boost to the economy.

WARREN: There's an upcoming $27 trillion market worldwide for green and much of what is needed has not yet been invented. My proposal is let's invent it here in the United States. And then say we invent it in the US, you've got to build it in the US.

DOERING: But even as she calls for harnessing the American labor force for a Green New Deal, Senator Warren says that in order to decarbonize the US economy, most of another major American resource, its oil, gas and coal reserves, will need to be left in the ground. At the Nevada debate, Elizabeth Warren said she’s willing to use the power of the presidency to that end.

WARREN: I think we should stop all new drilling and mining on public lands and all offshore drilling if we need to make exceptions because there are specific minerals that we've got to have access to, that we locate those, and we do it not in a way that just is about the profits of giant industries, but in a way that is sustainable for the environment. We cannot continue to let our public lands be used for profits by those who don't care about our environment and are not making it better.

Elizabeth Warren’s Blue New Deal looks to restore coastal fisheries through regenerative ocean farming, expand offshore wind and marine protected areas, and restore coastal ecosystems for carbon sequestration. (Photo: Michael Weidner, Unsplash, public domain)

DOERING: Senator Warren calls herself a staunch capitalist. Nevertheless, from the debate stage, she called out corporations that have far too much power in politics.

WARREN: Why can't we get anything passed in Washington on climate? Everyone understands the urgency, but we've got two problems. The first is corruption, an industry that makes its money felt all through Washington. The first thing I want to do in Washington is passing my anti-corruption bill so that we can start making the changes we need to make on climate and the second is the filibuster. If you're not willing to roll back the filibuster, then you're giving the fossil fuel industry a veto.

DOERING: That’s what happened back in 2009 when the House passed the Waxman-Markey cap and trade bill. It would have been a major step towards the US curbing its carbon emissions. A majority of Senators appeared to support the bill, and the Democrats were just one seat short of a filibuster-proof majority. But thanks to the filibuster threat, the bill quietly died before even reaching the Senate floor. And by the way, when Elizabeth Warren was elected to the Senate shortly thereafter, she unseated Republican Scott Brown, who had given the GOP that 41st seat needed to filibuster.

[APPLAUSE, MUSIC]

WARREN: Hello Keene!

DOERING: At a New Hampshire town hall, Senator Warren said the way the federal government is operating has dire consequences for the average American.

WARREN: It is a government that works great for giant oil companies that want to drill everywhere, just not for the rest of us who see climate change bearing down upon us. // And if we want to fix this, we can’t just nibble around the edges. If we want our democracy to work again, it’s gonna take some big structural change, and that’s why I’m here. Big Structural Change.

[APPLAUSE, CHEERS]

DOERING: On New Hampshire’s primary election eve, Elizabeth Warren held another town hall at South Church in Portsmouth.

[APPLAUSE, CHEERS]

DOERING: Voters gathered there expressed confidence in Senator Warren’s ability to get climate action done.

Senator Warren’s climate plan includes 100% renewable electricity generation, and the proliferation of electric vehicles to use that energy, by 2035. (Photo: Quinn Dombrowski, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

VOTER 1: It’s certainly got to be the main issue of our time, right? I mean, if we have no planet, does it really matter who we elect? So, I know, she’s been on board for the Green Deal for a long long time since it came out, and that also was a big factor for me.

VOTER 2: I’m a scientist, myself, an astronomer, and we’ve got maybe ten years to save the planet, basically. And I know she has a plan for climate change, and how we’ll address that. It’s vital, I’m becoming somewhat desperate and of course, it’s not my generation that’s gonna deal with the brunt of this, it’s those who come after us.

DOERING: One 14-year-old member of that next generation who attended the town hall is still too young to vote, but already passionate about climate policy.

KID: Climate change really bothers me, and I, like, I don’t want to be underwater by the time I’m my parents’ age; I want to be able to live without worrying about animals going extinct and cities flooding.

DOERING: The outcome of the 2020 Presidential election will either cement those fears further or give the world a chance at changing course on climate change. The Warren campaign is making a case that she’s the best person to lead the Democratic Party, and the country, into that uncertain future.

For Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

This story was produced with the help of Isaac Merson.

Related links:

- Click here to read Elizabeth Warren’s Climate Plans

- Inside Climate News | "Elizabeth Warren on Climate Change: Where the Candidate Stands"

- Click here for more analysis of Elizabeth Warren’s plan, after the adoption of Jay Inslee’s Climate Plan

[MUSIC: The Whaling City Sound Superband, “Thieves in the Temple” on A Killer Wail, by Prince, Whaling City Sound]

Investors Eye Climate Risk

BlackRock CEO Larry Fink warns that climate change poses an even greater risk than the 2008 financial crisis. (Photo: BrainMaY, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Climate change is already costing billions if not trillions of dollars around the world as cities flood and landscapes burn. And some in the investment community are warning that portfolios are at risk from climate disruption. Already JP Morgan Chase has decided it’s too risky for them to do business with coal companies or finance drilling in the Arctic. And asset manager giant BlackRock has declared climate change presents a greater risk to global finance than the 2007 recession. Black Rock has $7 trillion under management and its CEO Larry Fink is calling for a “fair and just” transition to a more sustainable economy. We’re joined now by Mindy Lubber, CEO and President of Ceres, an alliance of investors, corporations and activists. Mindy, welcome back to Living on Earth!

LUBBER: Great to be back. Good to see you.

CURWOOD: How will this move by BlackRock to put sustainability at the core of its investment practices shift the kinds of investment decisions it makes?

LUBBER: Well, they put out some goals, let's watch to make sure those goals are acted on. But as you know, Steve, over the last decade or so we've taken the issue, and "we" being much larger than Ceres, of climate risk of just being an environmental problem, to the economic problem that it is. Not only is the science telling us it really will change the life of the next generation in our kids, but it will also radically change the economy. Climate change has a negative impact on every sector of our economy. And we want to see climate risk being considered, just like any other risk when you're a company making decisions, or when you're an investor making decisions. So having Larry Fink Larry, and Fink runs BlackRock, it's an investment firm that manages $6.8 trillion in assets under management, and for any of us, $6.8 trillion is a lot of zeros. And when he says climate risk or climate change impacts his portfolio, and that they're going to start taking heavily coal-oriented companies out of their portfolio, and they're going to start evaluating companies in their portfolio based on their how they're managing climate change, that's good. That's a good addition to the fact that we already have 350 investors, $35 trillion in assets under management, working with us on climate change.

PG&E declared bankruptcy in 2019 as it faced some $30 billion in liabilities for damage from wildfires its aging equipment allegedly sparked in 2017 and 2018. (Photo: Coolcaesar, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: So what do you think prompted BlackRock and its CEO, Larry Fink, to sit up and say that, hey, we've got to move in this direction of handling climate risk? I mean, how involved has the company been in sustainable investing in the past?

LUBBER: Well, they've been slowly getting there. We've been working with them for a number of years and urging them to push forward and push harder. But any investor right now who is not looking at the fact that a country was on fire, meaning Australia, and what that means to every sector of the economy, or that PG&E, a publicly-traded Fortune 100 company, is in bankruptcy due to climatic changes, or that insurance companies are paying out hundreds of billions of dollars every year due to climatic changes. Those are real dollars, that's impacting the economy, and both Larry Fink as well as others in the financial sector are starting to see it and realize they've got to integrate it into their portfolio decisions.

CURWOOD: Now how is your organization, Ceres, going to hold BlackRock accountable for the promises that it's made to you and to the world to integrate sustainability in its investment decisions?

LUBBER: Well, there are a number of things. One is we'll look at what's in their actively managed portfolios, what companies are in and what is out. I mean, they were pretty specific: if a company gets more than 25% of its revenues from coal, over the next year, those companies are gonna be taken out of their portfolio, so we could take a look at that. If companies are ignoring sustainability metrics, they are going to come out of their portfolio, says BlackRock; we'll take a look at that. Now, BlackRock also said a number of other things. They said that they are going to vote their proxies; they've got a lot of clout with $6.8 trillion in assets under management, they're going to vote their proxy. That means when we all get these proxy statements around a company's annual meeting, they're going to vote against the management or the boards if those companies are not behaving in a responsible way on climate change. So on all fronts, BlackRock made a very clear statement. They're specific things; if they're not doing it, no doubt, we'll be doing benchmarking, sharing the results with the public. Many of our members, the large asset owners CalPERS, CalSTRS, the big public pension funds, are some of the largest clients of BlackRock. They've applauded the change and they'll be looking forward to making sure it's continuing to move forward.

Sea level rises poses a major risk to coastal property around the world. (Photo: Daniel Ramirez, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: For a number of years, the Securities and Exchange Commission has asked publicly-traded companies to say what they're doing about the climate in their annual reports, but there are no penalties. There are no requirements for what they put there. What the heck's going on?

LUBBER: It's a sad day as it relates to the SEC. In 2010 and 2011, the SEC put in place guidance that said, if you're a company that has material risk or real financial risk from climate change or water shortages, you need to disclose that risk like any other risk, like trade risk or currency risk or inflation risk or tax risk, you need to disclose it in the filings you make to the SEC. When investors want to invest in a company, they go to the SEC and they look at the filings of companies and they want to know, what are the risks of investing in those companies, as well as of course, the opportunities. And if the risk information isn't there, investors are being asked to make decisions blindfolded. It doesn't make sense, it doesn't reflect the real risks to our economy. And climate risk is very real, that's a mistake. We've seen federal government reports last year in this administration say climate risk could take 10% off the top of our economy over the next number of decades. That's a real risk.

BlackRock CEO Larry Fink. (Photo: Wilson Center, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: Mindy, what can our listeners do to ensure that their own investment strategies aren't exposed to too much climate risk, and maybe are even helping to build a more sustainable financial future?

LUBBER: Exactly. We've got to think about it and we've got to protect ourselves. One is we've got to look for the funds, the investment options that screen out fossil fuels or that only invest in clean energy. There are many, many options out there, number one. Number two, those options are getting competitive returns; there used to be a myth out there that you got to take a cut in your returns, if you're in environmentally or socially responsible funds. Now, every investment firm has a sustainable fund of some sort. So it's up to all of us to find those places to invest in. And secondly, when we get those things in the mail, or online now, our proxy statements, even if we own $2,000 in company X, we ought to look for those climate change resolutions. We have 175 on ballots of companies across the country right now. And vote those proxies, and say, we want this company to manage their climate risk in a responsible way; and more detail is laid out. So even as small investors, we've all got a role. We all got a responsibility, and we ought to act on it.

CURWOOD: Mindy, this conversation is so focused on climate risk. What are the other risks in the investment world when folks ignore sustainability?

At annual meetings, shareholders can vote for resolutions urging companies to adopt more sustainable practices and mitigate climate risk exposure. (Photo: Eni, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

LUBBER: Well, climate risk sort of is the overarching umbrella of all kinds of problems. But, water risk -- we are literally running out of water. The World Economic Forum says we'll have 40% less water by 2028 or 30. We can't run a society without adequate water. And we ought to look at human rights risks, which is part of a broader sustainability agenda, and reputational risks. If companies continue to ignore what's going on in their supply chain in Southeast Asia or somewhere else and they have 11-year-olds making their rugs and their carpets and so on, that too, is a great risk. So, we are all at risk if we don't start looking at these issues as the very real financial risks that they are.

CURWOOD: Mindy Lubber is CEO and President of Ceres, which works with investors and corporations to guide more sustainable practices. Mindy, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

LUBBER: Great. Thank you, Steve. Be well.

Related links:

- Read BlackRock CEO Larry Fink’s Letter to CEOs on climate risk

- Mindy Lubber in Forbes | “What It Means When The World’s Largest Asset Manager Rings A Warning Bell About The Financial Risks Of Climate Change”

- About Ceres and its new Accelerator for Sustainable Capital Markets

- Senator Elizabeth Warren and three colleagues pressed BlackRock for sustainability plan details

[MUSIC: es Obel, “Promise Keeper” on Myopia, by Agnes Obel, Deutsche Grammophon]

‘Parasite’ As Climate Fiction

In ‘Parasite’, a torrential downpour upends the Kims’ lives when it floods their basement apartment with sewage, while it merely rains out the Parks’ cushy camping trip. (Photo: ‘Parasite’ film still)

CURWOOD: The film “Parasite” made Oscar history when it became the first non-English language film to win Best Picture, in addition to rolling up Oscars for Best Director, Best Original Screenplay, and Best International Feature. For writer Ben Goldfarb of the blog “The Last Word On Nothing,” Parasite is also outstanding climate fiction.

GOLDFARB: Parasite, director Bong Joon Ho’s latest masterpiece, is a film about many things: class warfare, the indignities of capitalism, the eternal search for a WiFi signal. Less obviously, it’s also a work of climate fiction that illustrates the very real ways global warming worsens inequality.

Parasite revolves around two Korean families, the wealthy Parks, and the poor Kims. They’re divided not only by social status but by topography. The Parks live behind locked gates in a spotless, well-lit house, up a steep street in the Seoul highlands — a city on a hill. The Kims, who resourcefully infiltrate the Parks’ lives over the course of the movie, squat in a subterranean bunker in a low-elevation slum.

Bong emphasizes this altitudinal gradient. The Kims are forever hustling up and down the steep staircase that leads to their downtrodden neighborhood. While the Parks’ hilltop home feels clean and bright, the Kims’ area gives off a polluted vibe, shot in sickly greens and yellows.

Natural light and green space are accessible only by the wealthy in ‘Parasite’. The Park living room looks out on a lush garden hidden behind a high wall around their property. (Photo: ‘Parasite’ film still)

This difference isn’t just a symbol, it also drives the plot. Near the end of Parasite, a rainstorm causes a flash flood that submerges the Kims’ apartment, backs up sewage and forces them to abandon their few possessions — a humiliation that triggers the film’s chaotic final act.

This is a savvy understanding of how social class and urban geography collude to influence climate risk. Disaster after disaster, we’ve seen that lower-income neighborhoods at lower elevations are more susceptible to extreme weather, Hurricane Katrina and the Philippines’ Typhoon Haiyan being two obvious examples. One recent study showed that poorer people in Myanmar’s Bago City live in more fragile, flood-prone houses, trapping residents in a cycle of poverty.

An equally ominous study set in Miami-Dade County investigated a phenomenon called climate gentrification. The authors found that property values grow faster at higher elevations, away from the rising ocean, and that flooding has suppressed the value of low-elevation homes. Ultimately, researchers conclude, society’s growing preference for lofty heights “may lead to more widespread relocations that serve to gentrify higher elevation communities.”

Bong uses vertical movement and architecture to emphasize the socio-economic distance between the wealthy Park family and the poor Kim family. (Photo: ‘Parasite’ film still)

Bong Joon Ho has examined climate change and inequality before: In his dystopian thriller Snowpiercer, a failed geoengineering experiment turns the planet into an iceball, forcing the survivors onto a train with a brutal caste system. Parasite’s invocation of climate change is more subtle. Although the film never explicitly mentions global warming, it’s the inescapable backdrop, at once unobtrusive and ever-present, just as it is in real life. The Parks are oblivious to their climate privilege even as it shapes their world. The morning after the deluge that destroys the Kims’ home, the matriarch of the Park family chats on the phone with a friend from the backseat of her chauffeured car. “Did you see the sky today?” she says. “Crystal clear. Zero air pollution. Rain washed it all away.”

CURWOOD: Ben Goldfarb writes for the science blog, The Last Word On Nothing.

Related links:

- The Last Word on Nothing | “Parasite Is Great Cli-Fi”

- Watch: “The Ending of ‘Parasite’ Explained | Pop Culture Decoded”

- Watch: ‘Parasite’ Official Trailer

[MUSIC: Jung Jaeil, Opening theme from the film Parasite, licensed to Genie Music on behalf of Milan]

CURWOOD: Coming up – some surprisingly delightful things. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining a passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt, and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace Systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning in to the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at racetoninebillion.com.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Gary Beaudoin and the Boston Jazz Ensemble, “Willow Weep For Me” on In a Sentimental Mood, by Ann Ronell, North Star Records]

Beyond the Headlines

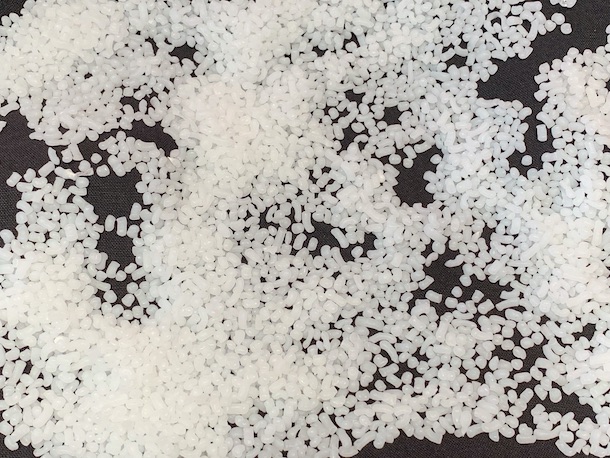

Plastic pellets are produced in ethane cracker plants which release air pollutants like benzene, toluene, and formaldehyde. (Photo: Mark Dixon, NoPetroPA, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood.

Time for us to take a look beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra from his perch down there in Atlanta, Georgia. Peter is an editor with environmental health news that's ehn. org a dailyclimate.org. What you're looking at this week, Peter?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve, you know, all the concern that we've heard just absolutely erupting over the past year on plastic pollution in the oceans and our streams and our landfills everywhere. There's another side to that, but it's not going to help very much.

CURWOOD: And that will be?

DYKSTRA: Cheap, fracked oil and gas is prompting a major build-out of plastics facilities in coal country where jobs are hard to find. And above Pittsburgh, there's a new plastics factory proposed for the Rust Belt area by Shell that will make literally billions of plastic pellets each year.

CURWOOD: Well, what kind of pushback is there against this?

DYKSTRA: Well, there's a bill in Congress. It's sponsored by many of the most prominent advocates of the Green New Deal, including Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. It calls for a three-year moratorium on new plastics plants, in Appalachia and elsewhere perhaps in Louisiana. That is a point of the Green New Deal, but it's unlikely to ever pass.

CURWOOD: And this isn't just the only controversy around fossil fuels in the news this week. Right?

Picture of an oil sand mine in Canada. The company Teck withdrew their application to the Canadian government to build the $15.6 billion oil sand mine Frontier project. (Photo: NWFblogs, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DYKSTRA: No it isn't and advocates for action on climate change might take a little bit more heart in this one. There's been an ongoing blockade of railways in Canada, in protest of the Canadian pipeline, proposed to run through First Nations territory, a Mohawk reservation in Ontario. The blockades have literally put a lot of Canadian rail traffic passenger trains and freight trains out of business for the time being. And it has the industry so spooked that a company called Teck has announced that they're dropping a fifteen-billion dollar tar sands mining project in Alberta. That pipeline would take fossil fuels, in this case, gas and move it from Western Canada to the big cities in Eastern Canada.

CURWOOD: Even as we record this, Peter, the price of oil seems to be down in response to the coronavirus outbreak. I think things are changing.

DYKSTRA: Things are changing, and we have no idea where we're going. But that one little thing is something that climate change advocates can take heart in.

CURWOOD: Alright now is the moment that we look back in history. Pull down that book from the shelf Peter and open it and tell me what you see.

DYKSTRA: Well, we'll blow the dust off the history book. You know, we haven't used it since last week. And we'll turn to March 7, 1998, when President Bill Clinton signed the bill making Lake Champlain, the sixth Great Lake.

Lake Champlain mostly lies between the states of Vermont and New York, with its northernmost tips in the Canadian province of Quebec. (Photo: Scott Ableman, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Okay, and why?

DYKSTRA: Well, it's certainly not for its great size. Lake Champlain has about six cubic miles of water in it. The next closest of the five original Great Lakes. Lake Ontario has about just short of 400 cubic miles of water in it. What it was about was not branding. It was about money, because being designated a great lake would mean that Champlain gets access to a cut of about a quarter-billion dollars in Great Lakes science and research and anti-pollution funding.

CURWOOD: I imagine that the five real Great Lakes weren't too happy about this.

DYKSTRA: Oh, they were Mean Girls. About 18 days after President Clinton signed that bill they got a compromise worked out where Champlain would not be allowed to call itself a great lake, but it would still have access to a cut of that money.

CURWOOD: So I guess it's a pretty good lake, huh?

DYKSTRA: Pretty good.

CURWOOD: Maybe someday they'll make Champlain great again. Hmm.

DYKSTRA: Maybe we'll have to have MCGA hats.

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra is an editor with environmental health news. That's ehn.org and daily climate.org. Thanks, Peter. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Okay, Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories at the Living on Earth website loe.org.

Related links:

- Congressional Democrats Join the Campaign Over Plastics Booming Future

- Cancelled Teck Oil Sands Project Underscores Global Climate Energy Policy Tension

- All That’s Interesting | “When Lake Champlain Became a Great Lake… For 18 Days”

[MUSIC: Buddy Holly, “Every day” on Sun Rise, by Norman Petty/Charles Hardin, Geffen Records (Rereleased by Sony Music)]

CURWOOD: Your comments on our program are always welcome. Call our listener line anytime at 617-287-4121. That's 617-287-4121. Our e-mail address is comments@loe.org, comments@loe.org And visits our web page at loe.org. That's loe.org

[MUSIC: Keola Beamer, E Ku’u Morning Dew, on Sun Rise, by Keola Beamer, Geffen Records (Rereleased by Sony Music)]

The Book of Delights

The Book of Delights is the first nonfiction book from poet Ross Gay, who dedicated a year to writing daily essays about the things that delight him. (Photo: Courtesy of Ross Gay)

CURWOOD: In an endangered world, gratitude and appreciation are difficult to balance with practical and existential fears. So to push back against fear, doubt, and gloom, poet Ross Gay took a moment almost every day for a year to write about something that delighted him and has published these observations in his latest volume, The Book of Delights. In this exercise, he found joy in everything from bumblebees to folding shirts at the laundromat and noticed beauty he had never seen before. Ross Gay spoke with Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb.

BASCOMB: So why write a book about delights? What inspired you to take on this project?

GAY: I was just in the middle of a, like a very pleasant walk. I was having a nice, delightful moment. And I thought, oh, how neat, it would, you know, just like, I could write about this. And then I thought, kind of quickly, oh, you know, it'd be interesting to write a book about something that delighted me every day for a year. And that's kind of how the idea for the project arrived.

BASCOMB: Mm-hmm. And you had a few rules of engagement for your project for writing about delight. Can you tell us about those?

GAY: Yeah, I was, I kind of wanted to write it every day. I didn't exactly get to that. But you know, pretty close. And I wanted to write the sort of quickly. And I wanted to write them by hand.

BASCOMB: You know, I wonder if that you know, leads you to a place where you're looking for something delightful where, you know, you're looking for something to be grateful for, in a sense.

GAY: To me that's one of the wonderful things about the exercise, or the practice was that I sort of realized that oh, I'm constantly in the midst of things that delight me that I have not yet realized delight me. And I haven't articulated them as delighting me, and I haven't shared them as delighting me. And then suddenly being, having the experience of being delighted more often, because now you recognize, oh, that's something that, that delights me. It's, it's really lovely. It's a really lovely thing.

BASCOMB: Can you give us an example of something that you didn't realize was delightful until you tried to put a word to it?

GAY: I'm delighted, by the way, that when people in a classroom, I'm often delighted by things in the classroom, if someone is reading, if we're reading in a circle, someone's going to read, and they're going to pass it along. I'm delighted, I mean, I love it. The pause between the sort of handing off from I'm reading and then the next person is going to read there's this sort of incredibly tender negotiation about how long should I wait and while you're done until I start, you know, these things like on and on, I love that thing. I love that thing.

BASCOMB: Now you find a lot of delight in the natural world. You have an essay in here about literally stopping to smell the flowers. There's, there are other essays about hummingbirds and praying mantis, fireflies, you talk a lot about your garden. To what extent do you think anyone can find delight in nature if they take the time to look?

GAY: When you look very closely, you know, the experience that I have often in a garden is looking very closely at a flower, or a plant, or something like that. And looking so closely that I realize, oh, I've never seen this before. You know, something that I see every day that it's in bloom or every day that it's making its fruit, something that I'm totally familiar with. When I slow down, which the garden encourages me to do, and I look in a different, slower way, kind of intentional way, I realize, whoa, I've never seen this before. And when I had that experience of whoa, I've never seen this before. I do have that experience, which I think is a lucky experience to be like, whoa, I've never seen anything before.

BASCOMB: To what degree do you think taking the time to appreciate the delights of nature can maybe make us better stewards of our environment?

GAY: I think basically what we do is, we care for what we love. You know, I think it's basically we care for what we love. And I think so often we, I think if we have the opportunity to articulate what it is that we love, then we are more likely then to tend to it and to care for it. So I do feel, I feel like it's absolutely part of the way that we are proper stewards of the land and we are properly entangled with the land and understand our entanglement with the land.

Ross Gay is an award-winning poet and the author of The Book of Delights. (Photo: Ross Gay)

BASCOMB: You also find delight in things that on the surface are not joyful at all. Things like being detained at the airport for extra security, a little pat down, and even enduring racism in your everyday life. How do you do that?

GAY: You know, the way that, if I think that, you know, something that I think is kind of interesting about this book is that it's a, it's sort of trying to like, you know, be a kind of adult book which is able to, or tries to practices articulating delight, articulating that which I love. And while at the same time articulating and understanding that the light does not exist, or the light exists often shoulder to shoulder with the brutal and what is not delightful, basically. So, yeah, a lot of these essays, you'll find that right next to something horrible is something, something not horrible or something delightful. And that's like one of them, to me, one of the interesting tensions of the book, is that sort of what feels to me like a grown understanding that, that many things are true at once, you know?

BASCOMB: Hmm. So maybe it's a delight in relief. Like you can't appreciate the delight of these things unless you've also known the painful aspects of life or the more difficult ones

GAY: Yeah, it's sort of like the light implies its absence you know? We know a delightful thing in part because we know an undelightful thing.

BASCOMB: Yeah, yeah, exactly. And so many of the delights that you're right about here are about intimacy, you know, those nicknames that your loved ones have for you or, or just these really passing interactions with strangers. You know the steward on the plane giving you a little arm pat, you know? Do you think that delightful moments like that are, are intimate by nature? I mean, there's the intimate relationship that you have with that bee in the flower but also with people.

GAY: Among my favorite experiences in this life are when people you know, someone sees a beautiful bird and they are looking at it and they see you and they point to it. Or there's a flower on a bush and someone is just sort of in it and says 'come on, you gotta smell this.' That thing which I think is like, I mean, I think it's one of our truest qualities, which is to share what we find beautiful. It's sharing, and I think sharing is a kind of, I haven't thought of it quite like this until you said it, but I think sharing itself is a kind of intimacy or, or probably, it suggests the possibility of intimacy.

BASCOMB: Do you have a copy of the book with you?

GAY: I do.

BASCOMB: Great. Would you mind reading a passage for us? I'm thinking of an essay called Black Bumblebees. It starts on page 262.

GAY: Yeah. Black Bumblebees. There is a kind of flowering bush, new to me, that I've been studying on my walks in Marfa. On that bush, whose blooms exude a curtain of syrupy fragrance, a beckoning of it, there are always a few thumb-size all-black bumblebees. Their wings appear when the light hits them right, metallic blue-green. I have never seen anything so beautiful. Everything about them- their purr, their wobbly veering from bloom to bloom- is the same as their cousins, the tiger-striped variety that shows up in droves when the cup plants in my garden are in bloom, making the back corner of my yard sound like a Harley convention. I wonder how I can encourage these beauties? These bees (though perhaps this observation is more about these flowers), mostly forego the sheer summer dresses, the pouty orifices of the blooms- though occasionally they dip in just enough to shiver the camisole- and instead land briefly on the outside of the flower, lumbering toward the juncture of or seen between the bloom and stem, where I imagine the nectar or pollen has dribbled or drifted. They then spin their legs into the base of the flower, shimmy some, swirl their abdomens for good measure and exhaling haul their furry bodies, gold-flecked, to the next bloom for more. I remembered, watching these bees, that among the delights of childhood was finding a patch of honeysuckle, sometimes with our noses and feasting on the nectar by plucking the flower from the vine, sliding the stamen free of the bloom, careful not to break it and sucking the faint sweetness dry. We would stay like that, licking flowers, sometimes for a half-hour. I'm pretty sure it was Joey Burns, at the time my best friend in the world, evidenced by the number of times we punch each other in the face, who introduced me when I was about six to the joys of honeysuckle plunder, for which I'd like to thank him. Though I do not thank him for the time he peed on me. And I do not want to praise myself too much. But I do consider it an innovation in honeysuckle when one time inspecting the flower I realized I might, without risking snapping the stamen, pluck the tiny bulbous stopper on the blooms bottom to tap the honey, as it were, in a kind of florid anilingus look into all the world. You're blowing the world's teeniest cornet. If only they knew.

CURWOOD: Ross Gay, reading from his volume, The Book of Delights. He spoke with Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb.

Related links:

- All things Ross Gay at his website

- Ross Gay giving a reading of an essay from The Book of Delights, ‘The Marfa Lights’

[MUSIC: Taj Mahal, “When I Feel the Sea Beneath My Soul” on Sun Rise, by Taj Mahal, Geffen Records (Rereleased by Sony Music)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Merlin Haxhiymeri, Don Lyman, Isaac Merson, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Anna Saldinger, Candice Siyun Ji, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, iTunes and Google play- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth