Measuring Our Worth

Air Date: Week of April 9, 2004

The Gross Domestic Product was designed to be a barometer for the economy, and was meant to indicate the country’s periods of boom and bust. But some economists believe this accounting equation leaves out some important factors, and now there’s a push to revamp the GDP system.

Transcript

[WALL STREET OPENING BELL]

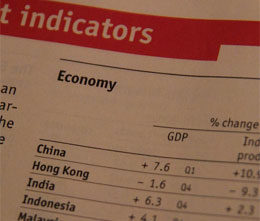

CURWOOD: When it comes to counting all the beans on Wall Street and in Washington, D.C., the only cookbook that matters is the Gross Domestic Product, or GDP. If the Gross Domestic Product is going up, people say the economy is growing. If the GDP is falling, they say we're in a recession. Whichever way it goes, investors, busines folks, voters s and presidential candidates use the GDP as an indicator of how well the nation is doing.

The GDP is supposed to measure the total production and consumption of goods and services in the United States. But the numbers that make up the Gross Domestic Product, by and large, only capture the monetary transactions we can put a dollar value on. Almost everything else is left out. And that's why some economists have a problem with this influential accounting system.

[CREAK OF SWING, CHILD’S LAUGH, ADULTS TALKING]

CURWOOD: At a playground in Cambridge, Massachusetts, a child is being attended by a daycare center employee. Her wages add to the GDP. Nearby, another child is being watched over by his grandmother. But, under GDP accounting rules, granny's contribution has no economic value.

The concept of the GDP was developed to help steer the U.S. economy out of the Great Depression and through World War II.

DAVIS: It was developed as a means of measuring economic output and, in fact, for planning purposes during the war period.

CURWOOD: Professor Graham Davis is an economist at the Colorado School of Mines.

DAVIS: But the public and the press, and probably some economists, have fallen into the trap of using GDP and, more specifically, growth in GDP as an indication of economic progress.

![]()

CURWOOD: Professor Davis cites coal mining as an example of how the Gross Domestic Product number can be a misleading growth indicator.

DAVIS: Every time we mine a ton of coal, GDP goes up by $17 a ton, but that doesn't take into account the fact that we've harvested one ton of coal from the Earth and that ton of coal is no longer there.

CURWOOD: So-called “green accountants” would add in depletion, says Professor Davis. And when you do that, the numbers start to change.

DAVIS: The value to society of that ton of coal in GDP terms would be about $17 for West Virginia coal. In green income terms, it would be about five dollars and 50 cents.

CURWOOD: And this adjustment only accounts for the decrease of coal in the ground and the depreciation of equipment used to mine it. It does not consider a potentially larger, human cost.

SCARBRO: I’ve contracted black lung, and also my hearing, I can’t hear anything

CURWOOD: James Scarbro is a retired West Virginia coal miner. He spent almost 32 years working in the mines.

SCARBRO: How does it affect me now? Well I can't do much work. I mean, I can get out here, and I can work a little bit, but I gotta gauge myself as I go about it. I've been into the hospital in and out for, I bet you, in the emergency room 10-15 times and it was with the symptoms of a heart attack.

CURWOOD: But Mr. Scarbo's medical bills aren't subtracted from the economic value of coal. Indeed, under the accounting system used by the Gross Domestic Product, his illness actually adds to the GDP. That's because medical costs to treat black lung disease add to the economy. So does the cost of cleaning up abandoned mines. If a coal slurry impoundment escapes and ruins miles of rivers, cleaning up that mess adds dollars to the GDP, too. So, in this case, environmental degradation looks good for the economy.

DALY: We add together benefits and costs, and changes in inventory – everything goes in. We don't subtract anything.

CURWOOD: That's Professor Herman Daly. He's an economist at the University of Maryland School of Public Affairs. He says a key flaw of the GDP is that it ignores core accounting principles of business.

DALY: A firm always has two accounts: they have a benefit account and a cost account. They have a revenue account and their expenditure account. They never add the two together. That would be the height of silliness. But that's exactly what we do with GDP.

CURWOOD: So some economists would argue that these are examples of some fundamental problems with the Gross Domestic Product. We don't measure unpaid work or services that may benefit society; we treat some expenses as income, and we often fail to value natural resources.

Back in 1993, the Bureau of Economic Analysis, the official bookkeeper of the U.S. economy, began responding to concerns that the GDP needed retooling. Director Steve Landefeld says the agency began working on a green accounting system called Integrated Environmental and Economic Accounts.

LANDEFIELD: We went forward trying to do, in a best-practice kind of way, a set of basic accounts where we began with the frankly more easily measurable commodities, such as petroleum and other mineral resources. In 1994, what we did was we tried to put together what we called a prototype set of accounts. The estimates were fairly significant.

[NOISES IN CAPITOL HILL HALLWAY]

CURWOOD: These initial results released in 1994 showed that GDP numbers were overstating the impact of mining companies to our nation's economic wealth. Mining companies didn't like those results, and it didn't take long for Capitol Hill to react.

Alan B. Mollohan, a Democratic House Representative from West Virginia's coal country, sponsored an amendment to the 1995 Appropriations Bill that stopped the Bureau of Economic Analysis from working on revising the GDP. And that's where things stand today. The Bureau of Economic Analysis is still not doing any work on revising the GDP in a way that considers such things as environmental impact accounting.

By the way, if the Bureau had focused its first work exclusively on forests instead of looking at coal and oil, the numbers might have been more appealing to present critics. Natural re-growth of trees has increased the economic value of our nation's forests by approximately 2 to 3.5 percent annually over the last half century. So, in some instances, accounting for the environment might actually boost economic indicators.

[SOUND OF KIDS PLAYING]

CURWOOD: Meanwhile, back at the playground in Cambridge, we are reminded of the work of sociologist Juliet Schor. She has been counting up the unpaid service part of our economy, from meals cooked at home to volunteers at local hospitals.

SCHOR: It turns out that the stuff we do that we don't get paid for is almost as big. Not quite anymore because the market sector has been increasing the fraction of human labor that it covers. Now, people are spending more of their time in the market. But it's a very, very large economy that's not included, almost as large as the one we measure.

CURWOOD: If the meal cooked at home is worth as much - or more - as the one served by a single mother employed at the local fast food joint, it changes the calculus of such programs as workfare. And if a tree that’s growing is worth as much or even more than one that is cut, that changes the calculus of forestry. Rethinking how we measure our economy raises broad questions. But Juliet Schor cautions that new statistics alone are not the answer.

SCHOR: We need new statistics, without question, but if we got the new statistics tomorrow, it wouldn't have solved the problem. We need a lot more than that. We also need a new set of incentives, we need new awareness, we need new kinds of human behavior, we need new power relationships. Those other things are really fundamental to making new statistics effective.

CURWOOD: Still, professor Herman Daly says one needs to start somewhere with correcting these statistics.

DALY: This really has nothing to do with green or brown or anything, it is just good economics.

CURWOOD: Our story on green accounting was produced by Gernot Wagner.

[MUSIC: Septeto Nacional de Ignacio Pinero “El Adios de este Momento” CUBA (Putumayo World Music – 1999)]

Links

Americans & Work article, CNNMoney.com

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth