April 9, 2004

Air Date: April 9, 2004

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

China Growth Costs

View the page for this story

The Chinese government announced recently that it will establish a “green GDP system” in an attempt to balance its economic needs with its environmental problems. Its economy has been growing at an unprecedented rate, at the expense of natural resources and air quality. Host Steve Curwood talks with the Council on Foreign Relations’ Elizabeth Economy about China’s environmental history, and how its new strategy might work. (12:47)

China’s Changing Market

View the page for this story

Within the past year, the price of food in the U.S. has risen. The demand for rice, grain, wheat and soybeans are at record highs, and supplies are running low. According to economist Lester Brown, the U.S. food industry will feel a squeeze to its resources soon, and the reason is not purely domestic. Host Steve Curwood talks with Lester Brown whose new book details why China will play a crucial role in setting U.S. food prices. (08:30)

Measuring Our Worth

View the page for this story

The Gross Domestic Product was designed to be a barometer for the economy, and was meant to indicate the country’s periods of boom and bust. But some economists believe this accounting equation leaves out some important factors, and now there’s a push to revamp the GDP system. (07:45)

Health Note/Drug Caution

/ Cynthia GraberView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Cynthia Graber reports on the growing use of anti-depressants among children and teens and how they may contribute to suicidal tendencies. (01:20)

Walking with Bears

/ Diane ToomeyView the page for this story

Thanks to a burgeoning black bear population in the U.S., there are more and more encounters between those animals and humans. But researcher Lynn Rogers says only rarely is there anything to fear. Diane Toomey went on a walk in the woods with the bear scientist. (10:45)

Thawing Scents

/ Verlyn KinkenborgView the page for this story

Commentator Verlyn Kinkenborg tells us why he knows when spring has come to his home in rural New York. He can smell the skunks again. (03:30)

This week's EarthEar selection

listen /

download

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve CurwoodGUESTS: Elizabeth Economy, Lester BrownREPORTER: Gernot WagnerCOMMENTARY: Verlyn KlinkenborgNOTES: Cynthia Graber

[THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: From NPR - this is Living on Earth.

[THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. China’s amazing economic growth has come at a huge cost to its ecosystems, and its government now says it’s time to factor in environmental damage when taking the pulse of the economy. The move is drawing praise and raising eyebrows.

ECONOMY: Frankly, I take the attitude of I’ll believe it when I see it. And I think the Chinese who are involved in this process have acknowledged themselves that it’s going to be a very difficult and complicated process.

CURWOOD: Also, how counting the cost of pollution and resource depletion could change how we figure the gross domestic product here in the U.S.

DAVIS: The value to society of that ton of coal in GDP terms would be about $17 for West Virginia coal. In green income terms, it would be about five dollars and 50 cents.

CURWOOD: Green accounting practices, and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NPR NEWSCAST]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the National Science Foundation and Stonyfield Farm.

China Growth Costs

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Somerville, Massachusetts, welcome to Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

We turn our attention this week to the emerging giant - China. Over the past decades, China has been growing its economy twice as fast as the United States, churning out everything from clothing and car parts to computer chips and coal plants. In the process, America has become one of China’s biggest customers and China has become one of America’s biggest creditors. We’re running up a tab to the Chinese of over $100 billion dollars a year. The U.S. debt to China is likely to have an impact on food prices here in the United States in the years ahead, and we’ll have more on that later in the broadcast.

But first, we turn our attention to the toll that rapid economic growth is taking on China’s environment. Land, air and water quality are deteriorating, and recently, the government announced plans to explore a green accounting system to calculate environmental costs related to economic growth.

Joining me to discuss its potential is Elizabeth Economy. She is a senior fellow at the New York City-based think tank, the Council on Foreign Relations, and author of “The River Runs Black: The Environmental Challenge to China’s Future.” Elizabeth, hello.

ECONOMY: Hello, Steve.

CURWOOD: Now, you write that the roots of many of China’s current environmental problems stem from its past, and particularly you point at Mao Zedong’s cultural revolution. Could you explain what you mean by this?

ECONOMY: Sure. Even before Mao Zedong, I think, it’s important to understand that China has degraded its environment for centuries. A lot of people ask me, well, how does China really differ from the United States? I mean, it’s just going through its process of industrialization just as we did, and you can expect there to be environmental costs and consequences.

But the point that I try to make is that China is starting from a very different place than the United States did. War was really a constant fixture in China for centuries. And this meant that you had rampant deforestation for fuel, they were mining for ore. And then these wars were followed by periods of very rapid economic development and growth in which the leaders would try to reclaim land for agriculture but the land was already eroded. This contributed to desertification.

And another sort of interesting fact was the population issue in China. Again, one that people think is a relatively recent one – the fact the China does have a little bit over a fifth of the world’s population. Population pressures were already felt by 1400. There were already a hundred million people. And by the Tang dynasty, roughly 600 A.D., there were already reports of areas in China where overpopulation was a problem, where there were too many people for the resources and the land, and you had migration in search of arable land and better water resources.

CURWOOD: So, what you’re saying then, is what happened under Mao Zedong in the last 50 years or so is really just a reflection of what had happened centuries before.

ECONOMY: That’s right. I think it provided a building block for Mao. Mao really ramped up the degradation of the environment. He called for nothing short of a war against nature. And you had probably some of the worst excesses in Chinese history take place under Mao. You know, back yard steel furnaces, moving polluting industries into pristine parts of the Chinese countryside in order to protect them from what Mao believed would be foreign attacks, attacks from the United States. You had the “great leap forward” in which wetlands and forestlands were reclaimed for agriculture, so you had wide-scale deforestation during this period. So there were some of the worst excesses. But I think it’s important to understand that this is a problem that is centuries in the making.

CURWOOD: Now, of course, today China is moving into the forefront of the international market with an unprecedented rate of productivity and development and growth. What are the sectors that you see are really jumping up in terms of growth?

ECONOMY: Well, at this point in time, China is becoming one of the largest producers of electronics. It’s basically hollowing out the semiconductor industries from the United States and from Taiwan. It has become the second largest importer of oil after the United States. The housing sector is booming. Infrastructure, roads, railroads. You can almost look at any area and say that China’s economy is booming. The auto sector is another one that has really taken off over the past few years.

CURWOOD: So as a result of this economic boom, Elizabeth, what do you see are some of the most pressing environmental challenges that China now faces?

ECONOMY: Well, you know, at this point, demand for water, for example, is growing at a rate of about 10 percent a year in cities, and about five percent for industry. But this is on top of a situation in which 60 million people in the country find it difficult to get enough water for their daily needs.

Energy also, of course. China’s had, traditionally, an overwhelming reliance on coal. A little bit over two thirds of its energy comes from coal, and oil makes up about a quarter, and the rest – some very small amount – comes from cleaner energy sources like natural gas and hydropower. And I think that – not only in terms of the demand side where, as you probably know, China experienced wide-scale power outages over the past year – but also in terms of the pollution. You know, China today boasts 16 of the 20 most polluted cities in the world.

There are other issues that the environment is having an impact on. For example, migration. The fact is that the Chinese government expects that 30 to 40 million Chinese are going to have to migrate by 2025 in search of better land or because they don’t have access to water. I mean, a quarter of China is desert today. And think of it in terms of the fact that China is the same size as the United States. So imagine if a quarter of the United States were desert. And the desert is advancing very rapidly at a rate of about 900 square miles per year. And they have these sand storms that afflict the coastal cities in Asia. So there are these visible signs, and then sort of secondary impacts that the Chinese people themselves feel quite directly.

CURWOOD: Recently, the Chinese government announced that it will develop a green GDP system in order to cut down on its environmental pollution. Please explain how this might work.

ECONOMY: Frankly, I take the attitude of I’ll believe it when I see it. I think environmental natural resource accounting in this country is still relatively poorly developed. And I’m not sure how the Chinese government is planning to do this. I mean, the World Bank and some Chinese economists have done the best estimates of trying to account for environmental degradation and pollution in sort of assessing where the Chinese GDP really is and in terms of what costs are being inflicted on the Chinese population and the Chinese economy from environmental degradation and pollution. But, as I think the Chinese who are involved in this process have acknowledged themselves, it’s going to be a very difficult and complicated process.

CURWOOD: In terms of the green GDP, I’ve read somewhere that they’re going to list environmental changes separately, and their impact on economic growth. How would that work?

ECONOMY: Well, you would look at factory shutdowns because of energy shortages, or factory shutdowns because of lack of access to water. So you might have a coal mine – for example, there’s a major coal mine, Datong in central China, that they estimate loses $100 million a year because it doesn’t have enough water to wash its coal. So that would be the kind of thing that they would do, to list the costs separately.

CURWOOD: Now, one of the things you write in your book is that there’s an estimate of, what, eight to 10 percent of the GDP in China is being lost to environmental degradation. What do you suppose accounts for this?

ECONOMY: That’s right. These are estimates that began to be developed in the mid-1990s by the World Bank and also by western economists and Chinese economists working together. Those numbers reflect a wide range of inputs. They include everything from the cost to the Chinese economy from workers missing days of work and being hospitalized due to respiratory problems from air pollution, to loss of crops because of contaminated water because of acid rain, to factories being shut down because of loss of water. And also, I should say, agricultural land being lost from desertification. So these numbers include the full range of environmental inputs.

CURWOOD: Help me understand the thinking of the Chinese government. Why tackle China’s environmental problems from an economic standpoint? What’s the advantage in doing that?

ECONOMY: Well, I think that it’s part of a broader move within the Chinese government as it transitions from a socialist command economy to a market economy, and sort of use the economy in some ways to advance environmental protection. For example, you have China experimenting with practices that were developed in the United States, for example, on tradable emissions, permits for sulfur dioxide. I think there’s definitely – it’s an admirable goal. The question is only how is it actually going to be affected?

CURWOOD: Tell me, what’s at stake for the United States in all this? What interest is there for Americans in China’s environmental future other than being world citizens?

ECONOMY: Well, I think that the interests are two-fold, if not more, perhaps. First of all, of course, China’s environmental practices have a direct impact on the global environment – everything from biodiversity loss to global climate change, where China is now the second largest contributor to global climate change in the world, right now. The dust storms that I mentioned, the sand storms, actually not only affected Asia, but a few years back found that the dust had traveled to California and even beyond, causing a spike in respiratory problems on the west coast of the United States.

Second, I think for anybody who’s interested in trying to understand where China may be going in the future, the environment is critical. There is the question of China’s demand for world resources for oil, for coal, what’s it going to do diplomatically and internationally? You know, are we going to find a more aggressive China in the South China Sea, for example, asserting its rights for natural gas? So there’s this kind of interplay.

But I also think on a somewhat deeper, maybe more profound level, there is the potential for the environment in China to serve as a catalyst for broader political reform. And you’ve just begun to see in China, now, the environmental movement -- which really began only a decade ago with China’s first environmental NGO -- move from sort of environmental education to very aggressive lobbying of the government, and to change policy. You know, preventing dams from being built. So these are the kinds of developments that I think are important to understand for anyone who’s interested in understanding the future of China.

CURWOOD: Elizabeth Economy is a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations. She’s author of “The River Runs Black: The Environmental Challenge to China’s Future.” Elizabeth, thanks so much for taking this time with me today.

ECONOMY: Thank you, Steve.

CURWOOD: Coming up: as China’s population and its economy grows, it’s running out of land to farm and water to grow crops. But it does have plenty of money to buy food from abroad, says my next guest. And soon, he predicts, we’ll feel rising food prices in our own wallets. Stay tuned to NPR’s Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: CBMW “Sambasunda” THE ROUGH GUIDE TO THE MUSIC OF INDONESIA (World Music Network – 2000)]

China’s Changing Market

CURWOOD: Welcome back to Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood.

If you don’t like the way prices have been rising at the gasoline pump these days, you may soon have another budget worry: higher food prices. In the past seven months, the price of soybeans has doubled as China has bought up 13 percent of the world’s supply to make up for a declining harvest. Rice is up by 80 percent and wheat is up as well.

Over the years grain prices can go up and down but according to former Agriculture Department official Lester Brown, these recent whopping increases may well be reflecting some fundamental changes in the forces that affect the world’s food supply.

Lester Brown is now president of the Earth Policy Institute and author of “Plan B: Rescuing a Planet Under Stress and a Civilization in Trouble.” Lester Brown, you say food is going to cost us a lot more. How come?

BROWN: Well, there are two new environmental trends that are now affecting the food prospect. One is falling water tables, and they’re falling in scores of countries around the world as a result of over-pumping. This is historically a new trend, one we’ve not had much experience with because we didn’t have the pumping capacity that we have today.

Diesel pumps, powerful electrically driven pumps, enable us to literally deplete aquifers. And that’s what’s happening. It’s happening in China, it’s happening in India, it’s happening in the United States, just to cite the big three grain producers that account for half the world grain harvest. So spreading water shortages are now beginning to – are making it more difficult for farmers to expand food production fast enough to keep up with the 70 million people being added each year.

The second new trend that’s making it difficult for them is higher temperatures, in many cases, crop-withering temperatures. Recent research by crop ecologists indicate that crop yields are much more sensitive to temperature than we had earlier realized. And so we’re seeing – last year we saw crop yields sharply reduced in India and the United States because of intense heat and the drought that often comes as a result of it. And this year it was Europe that really bore the brunt of higher temperatures.

CURWOOD: Okay, but you say that we’re going to see higher food prices as the impact of what’s going on environmentally in just this next year or two or three. Why now?

BROWN: For the last eight years world grain production has been flat. It has not increased at all. But demand has continued to rise. So for the last four years, world grain production has fallen short of consumption. So these harvest shortfalls have been covered by drawing down world grain stocks which, at the end of this year, will be at the lowest level in 30 years. We’ve only been this low once before.

CURWOOD: When was that?

BROWN: 1972, ’74, when wheat and rice prices doubled. That’s when the Soviets secretly cornered the world wheat market in 1972, and then we had a poor harvest the next year and things got pretty hairy there for a while. So, we’re now looking at very low stocks. We’re looking at each of the last two years at a crop shortfall, a grain shortfall of 90 million tons. And the big question is whether next year the world’s farmers can dig their way out of this 90 million-ton hole and feed 70 million more people.

CURWOOD: You don’t think they can?

BROWN: It’s going to be difficult. It’s going to be difficult. It’s not impossible. If we had really good weather in all the major food producing regions they could probably do it. But that rarely ever happens.

CURWOOD: So how does China figure into this?

BROWN: China is a big part of the world and part of the shortfalls are coming in China. From 1950 to 1998, China increased its grain harvest from 90 million tons to 392 million tons. It was one of the great economic success stories of the last half-century. But then, in 1998, it peaked and it’s been declining since then, partly because of water shortages. China’s grain harvests have dropped from 392 million tons in 1998 to 326 million tons in 2003. So in five years it’s dropped by more than 60 million tons. That’s more than the Canadian grain harvest, just to put it in perspective. It’s also more than the exports of Canada, Australia, and Argentina combined.

CURWOOD: Okay, so what you’re saying is that China is growing less and less grain for itself…

BROWN: And its demand is going up each year.

CURWOOD: Okay. And you’re saying this is going to raise world food prices.

BROWN: China’s been covering this shortfall, this downturn over the last four years or so, by drawing down their stocks. They had huge stocks but those stocks are now largely drawn down. They may be able to draw down one more year, at most. And then they’re going to have to come to the world market to cover this shortfall. And when they do, they’ll be wanting to import more grain than any country’s ever imported in history. And when they come to the world market, they will necessarily come to the United States because we control almost half the world’s grain exports. And this is going to create a fascinating geopolitical situation because it’s almost inevitable that we’re going to see this. That is, 1.3 billion Chinese consumers with a hundred billion dollar trade surplus with the United States competing with us for our food and driving up food prices.

CURWOOD: Now, you just came back from China. What did you see that lends credence to your view that they’re going to have a serious food problem in this next year or two?

BROWN: Well, for example, traveling by train from Beijing to the capital of Inner Mongolia, Hohhot, and then from there to Lanzhou in the upper Yellow River Valley across the northern part of China – you see sand dunes, for example. You’ll be going through a plain that’s irrigated and green, and suddenly, out of nowhere, you’ll see sand dunes 10 feet tall. And these are dunes that are forming because of a loss of vegetation in the un-irrigated area away from the river floodplains, for example.

China has enormous numbers of cattle and sheep, goats. In this country we have 97 million head of cattle. China has 127 million head. We have 8 million sheep and goats in this country. China has 280 million sheep and goats, most of them in the northern and western part of the country. They’re literally de-vegetating the country, I mean, you can see it, you see them everywhere as you travel about the country. And you see the drifting sand and the sand dunes.

You see along the railroad tracks, for example – you know how we put up snow fences to trap drifting snow to keep it off of highways? They do things like that for sand because when sand covers the tracks trains can’t get through. If it’s snow, trains are heavy enough to handle snow. But they can’t handle sand; they’ll often derail. So, it’s a serious challenge for the transportation system. To keep it functioning you have to keep the sand off the tracks.

CURWOOD: So, I’m wondering if you feel that China’s headed for a crash. That is, it has expanded -- perhaps developed itself too quickly and in an unsustainable way -- and will face great troubles in the years ahead?

BROWN: In economic terms, I mean, they get an A+ in terms of economic growth, reducing poverty, eradicating most of the hunger in the country. And China today has a food cushion. It’s not that China is on the verge of starvation; it’s that China is growing and consuming more and more food and is going to begin to need a lot of that from the outside world. And it’s the effect of that on the outside world that is of major concern to me, and to the U.S. intelligence community, as well. Because China has the purchasing capacity – the 100 billion dollar trade surplus that China has with the United States now is enough to buy the entire U.S. grain harvest twice. I mean, that’s just the surplus they have with us. So it’s not a question of can they afford to compete with us for our grain. They can, and they will.

CURWOOD: Lester Brown is author of “Plan B: Rescuing a Planet Under Stress and a Civilization in Trouble.” Thanks for taking this time with me today.

BROWN: My pleasure, Steve. Thank you.

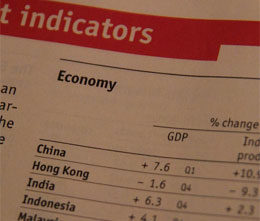

Measuring Our Worth

[WALL STREET OPENING BELL]

CURWOOD: When it comes to counting all the beans on Wall Street and in Washington, D.C., the only cookbook that matters is the Gross Domestic Product, or GDP. If the Gross Domestic Product is going up, people say the economy is growing. If the GDP is falling, they say we're in a recession. Whichever way it goes, investors, busines folks, voters s and presidential candidates use the GDP as an indicator of how well the nation is doing.

The GDP is supposed to measure the total production and consumption of goods and services in the United States. But the numbers that make up the Gross Domestic Product, by and large, only capture the monetary transactions we can put a dollar value on. Almost everything else is left out. And that's why some economists have a problem with this influential accounting system.

[CREAK OF SWING, CHILD’S LAUGH, ADULTS TALKING]

CURWOOD: At a playground in Cambridge, Massachusetts, a child is being attended by a daycare center employee. Her wages add to the GDP. Nearby, another child is being watched over by his grandmother. But, under GDP accounting rules, granny's contribution has no economic value.

The concept of the GDP was developed to help steer the U.S. economy out of the Great Depression and through World War II.

DAVIS: It was developed as a means of measuring economic output and, in fact, for planning purposes during the war period.

CURWOOD: Professor Graham Davis is an economist at the Colorado School of Mines.

DAVIS: But the public and the press, and probably some economists, have fallen into the trap of using GDP and, more specifically, growth in GDP as an indication of economic progress.

![]()

CURWOOD: Professor Davis cites coal mining as an example of how the Gross Domestic Product number can be a misleading growth indicator.

DAVIS: Every time we mine a ton of coal, GDP goes up by $17 a ton, but that doesn't take into account the fact that we've harvested one ton of coal from the Earth and that ton of coal is no longer there.

CURWOOD: So-called “green accountants” would add in depletion, says Professor Davis. And when you do that, the numbers start to change.

DAVIS: The value to society of that ton of coal in GDP terms would be about $17 for West Virginia coal. In green income terms, it would be about five dollars and 50 cents.

CURWOOD: And this adjustment only accounts for the decrease of coal in the ground and the depreciation of equipment used to mine it. It does not consider a potentially larger, human cost.

SCARBRO: I’ve contracted black lung, and also my hearing, I can’t hear anything

CURWOOD: James Scarbro is a retired West Virginia coal miner. He spent almost 32 years working in the mines.

SCARBRO: How does it affect me now? Well I can't do much work. I mean, I can get out here, and I can work a little bit, but I gotta gauge myself as I go about it. I've been into the hospital in and out for, I bet you, in the emergency room 10-15 times and it was with the symptoms of a heart attack.

CURWOOD: But Mr. Scarbo's medical bills aren't subtracted from the economic value of coal. Indeed, under the accounting system used by the Gross Domestic Product, his illness actually adds to the GDP. That's because medical costs to treat black lung disease add to the economy. So does the cost of cleaning up abandoned mines. If a coal slurry impoundment escapes and ruins miles of rivers, cleaning up that mess adds dollars to the GDP, too. So, in this case, environmental degradation looks good for the economy.

DALY: We add together benefits and costs, and changes in inventory – everything goes in. We don't subtract anything.

CURWOOD: That's Professor Herman Daly. He's an economist at the University of Maryland School of Public Affairs. He says a key flaw of the GDP is that it ignores core accounting principles of business.

DALY: A firm always has two accounts: they have a benefit account and a cost account. They have a revenue account and their expenditure account. They never add the two together. That would be the height of silliness. But that's exactly what we do with GDP.

CURWOOD: So some economists would argue that these are examples of some fundamental problems with the Gross Domestic Product. We don't measure unpaid work or services that may benefit society; we treat some expenses as income, and we often fail to value natural resources.

Back in 1993, the Bureau of Economic Analysis, the official bookkeeper of the U.S. economy, began responding to concerns that the GDP needed retooling. Director Steve Landefeld says the agency began working on a green accounting system called Integrated Environmental and Economic Accounts.

LANDEFIELD: We went forward trying to do, in a best-practice kind of way, a set of basic accounts where we began with the frankly more easily measurable commodities, such as petroleum and other mineral resources. In 1994, what we did was we tried to put together what we called a prototype set of accounts. The estimates were fairly significant.

[NOISES IN CAPITOL HILL HALLWAY]

CURWOOD: These initial results released in 1994 showed that GDP numbers were overstating the impact of mining companies to our nation's economic wealth. Mining companies didn't like those results, and it didn't take long for Capitol Hill to react.

Alan B. Mollohan, a Democratic House Representative from West Virginia's coal country, sponsored an amendment to the 1995 Appropriations Bill that stopped the Bureau of Economic Analysis from working on revising the GDP. And that's where things stand today. The Bureau of Economic Analysis is still not doing any work on revising the GDP in a way that considers such things as environmental impact accounting.

By the way, if the Bureau had focused its first work exclusively on forests instead of looking at coal and oil, the numbers might have been more appealing to present critics. Natural re-growth of trees has increased the economic value of our nation's forests by approximately 2 to 3.5 percent annually over the last half century. So, in some instances, accounting for the environment might actually boost economic indicators.

[SOUND OF KIDS PLAYING]

CURWOOD: Meanwhile, back at the playground in Cambridge, we are reminded of the work of sociologist Juliet Schor. She has been counting up the unpaid service part of our economy, from meals cooked at home to volunteers at local hospitals.

SCHOR: It turns out that the stuff we do that we don't get paid for is almost as big. Not quite anymore because the market sector has been increasing the fraction of human labor that it covers. Now, people are spending more of their time in the market. But it's a very, very large economy that's not included, almost as large as the one we measure.

CURWOOD: If the meal cooked at home is worth as much - or more - as the one served by a single mother employed at the local fast food joint, it changes the calculus of such programs as workfare. And if a tree that’s growing is worth as much or even more than one that is cut, that changes the calculus of forestry. Rethinking how we measure our economy raises broad questions. But Juliet Schor cautions that new statistics alone are not the answer.

SCHOR: We need new statistics, without question, but if we got the new statistics tomorrow, it wouldn't have solved the problem. We need a lot more than that. We also need a new set of incentives, we need new awareness, we need new kinds of human behavior, we need new power relationships. Those other things are really fundamental to making new statistics effective.

CURWOOD: Still, professor Herman Daly says one needs to start somewhere with correcting these statistics.

DALY: This really has nothing to do with green or brown or anything, it is just good economics.

CURWOOD: Our story on green accounting was produced by Gernot Wagner.

[MUSIC: Septeto Nacional de Ignacio Pinero “El Adios de este Momento” CUBA (Putumayo World Music – 1999)]

Related links:

- Americans & Work article, CNNMoney.com

- Dr. Herman Daly

- Dr. Steve Landefeld, Bureau Economic Analysis

- Dr. Graham Davis

- Dr. Juliet Schor

Health Note/Drug Caution

CURWOOD: Just ahead: the private lives of bears. First, this Environmental Health Note from Cynthia Graber.

[HEALTH NOTE THEME]

GRABER: Recent reports have linked the use of anti-depressants by children and teenagers to an increased risk for suicide. So, the Food and Drug Administration is recommending that certain drugs not be used by adolescents because of this risk. Now, a new study shows just how much is at stake.

According to a report published in this month's issue of Psychiatric Services, the number of kids taking antidepressants grew by almost fifty percent from 1998 to 2002. Preschoolers were the fastest-growing group of all, with use among girls doubling and use among boys up by sixty-four percent. Researchers also say that the number of children taking antidepressants increased by almost 10 percent each year over the past five years, and they expect this trend to continue even though studies show that the drugs are only modestly effective at treating depression within this group.

The scientists involved in the study had no conclusive reason for the increase in drug use. They point to increasing rates of childhood depression, a growing awareness of depression by doctors, and a shift away from mental health services like psychotherapy in favor of pharmaceutical treatments as possible factors. But the researchers were clear on one conclusion: they say more work is needed to determine the appropriateness of prescribing antidepressants to youngsters, one of the most vulnerable patient populations. That’s this week’s Health Note, I’m Cynthia Graber.

CURWOOD: And you’re listening to NPR’s Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for NPR comes from NPR stations, and: Aveda - an Earth-conscious beauty company committed to preserving natural resources and finding more sustainable ways of doing business. Information available at Aveda.com; The Noyce Foundation, dedicated to improving Math and Science instruction from kindergarten through grade 12; The Annenberg Foundation; and, The Kellogg Foundation, helping people help themselves by investing in individuals, their families, and their communities. On the web at wkkf.org. This is NPR, National Public Radio.

[MUSIC: L.S. Gelik “Jeruk Manis” THE ROUGH GUIDE TO THE MUSIC OF INDONESIA (World Music Network – 2000)]

Walking with Bears

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood and coming up: the first breath – or sniff? – of spring. But first: black bears. They are coming back in earnest in the eastern United States. Where I live – about an hour outside of Boston – a mother bear and her cub were spotted just down the road a piece.

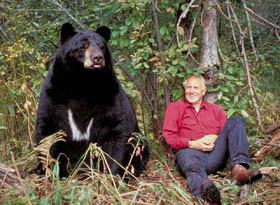

And last fall in New Jersey there were so many black bears the state held its first bear hunt in more than three decades. Bear and human interactions are way up in many parts of the country, ranging from backyard encounters to bears entering homes to raid kitchens. And one researcher says any problems lay with the attitudes of humans. Diane Toomey has this profile of bear scientist Lynn Rogers.

TOOMEY: It’s a chilly morning on the Massachusetts side of the Berkshire mountains. About a dozen people are gathered here today, in black bear country, in the hopes of tracking a bear.

MAN: I’m here to meet people who like bears and to learn something.

TOOMEY: But even among this crowd, there’s a bit of trepidation. This woman recently had a close encounter with a bear right outside her front glass door.

WOMAN: I was face to face with this bear looking in. [LAUGHTER] And that really scared me. But I love the bears and I’m trying to work through that experience! [LAUGHTER]

TOOMEY: For that kind of fear, there’s no better therapist than wildlife biologist Lynn Rogers.

[FOOTSTEPS IN THE WOODS]

ROGERS: When a bear shows up in somebody’s yard, whether that’s a nuisance or a joy depends on the person’s attitude.

Dr. Lynn Rogers

Dr. Lynn Rogers

TOOMEY: Sixty-four-year-old Lynn Rogers, six feet tall with shoulders to match, looks like, you guessed it, a bear. He even sounds a bit like Smokey, that most famous of black bears. And when the group picks up the trail of a bear, and Rogers stops to investigate, you’ll see he shares some of the animal’s tastes.

ROGERS: Here's one the bear missed. Hmm. I like nuts and berries. This is a beechnut. Really good! Bears are no dummies.

[LAUGHTER]

TOOMEY: Rogers began his research 35 years ago in northern Minnesota, studying basic bear biology. He was the first researcher to draw blood from wild hibernating bears and did pioneering work in describing the matriarchal nature of bear society in which mothers bequeath part of their territory to daughters.

His research, using radio telemetry to follow as many as four generations of family groups, has been praised by E.O. Wilson as one of the greatest wildlife studies of all time. But Rogers eventually turned to, what he describes as, the least studied area of bear biology – the bear/human interface.

ROGERS: There’s people making a living trying to scare us about bears. Telling and re-telling the stories of killings by bears. But there’s only been 52 killings by black bears in the last 100 years across North America.

TOOMEY: So for every human killed by a black bear, Rogers says, 45 are killed by dogs, 120 by bees and hornets, and 60,000 people are killed each year by a fellow human.

ROGERS: That’s why I feel safest walking in the woods right next to a bear!

TOOMEY: With the help of tracker John McCarter, the group is walking through a light dusting of snow in the hopes of backtracking a bear, tracing its movements back in time and moving away from the actual animal. But it’s looks like we’ve gotten too close for comfort.

MCCARTER: And see how the leaves are all scuffed down? The bear stopped abruptly here. And if you look right down there where the bear was facing? That points down to the swamp we were in earlier. And then the bear did a 45-degree turn here, hard and fast, and ran off that way.

ROGERS: It shows just the extent to which bears try to avoid people. Here’s a bear, two, three hundred yards from us. Not only did it avoid us, I mean it ran to get away from us while we were still that far away.

TOOMEY: Rogers’ knowledge of black bears comes from a unique perspective – a distance of about five to 10 yards. It’s a research technique no one else has tried with bears.

ROGERS: After hundreds of hours of trying to get near a bear and get it to accept me, finally I get to the point where I can walk with it, sleep with it, record detailed data as it ignores me. I’m not a friend, I’m not an enemy. I’m not a competitor, I’m not a food giver. I’m just there.

TOOMEY: On these 24-hour walks, Rogers carries no food or water, barely sleeps, and just simply…observes.

ROGERS: And the bears just go about their business of making a living, tearing open logs to get ants, foraging for berries, or hazelnuts, whatever. I learned their vocalizations and body language and how they raise their cubs. I learned what bears are really like.

TOOMEY: While Rogers may acclimate a bear to his presence in one part of the forest, he says that same bear may be spooked by him in another. So to get past this, Rogers often does something that sounds pretty dangerous.

ROGERS: Sometimes you have to wait till they have cubs. Then when the mother is in there with the cubs, that kind of holds her in place, and I can set up a a little office outside that den. With a sleeping bag, a laptop computer, and a cell phone. And they gotta just get used to me being there. And by the time they emerge in the spring, I’m just part of the woodwork.

TOOMEY: Or part of the family, as he puts it. This technique wouldn't be possible with a grizzly bear. That’s because grizzly mothers are hard-wired to protect their cubs. Indeed, 70 percent of grizzly killings are by mothers doing just that. But Rogers says no one has been killed by a black bear defending offspring. He has a theory about why this species has, in his words, come to be ruled by fear.

ROGERS: I think part of it goes back to the Ice Ages, when they were living along such powerful predators as saber tooth cats, American lions, dire wolves (sp). Powerful predators black bears wouldn’t have stood a chance against any of them. But black bears could survive because they were the only one that could climb a tree, and they had this attitude of run first and ask questions later. The timid ones apparently passed on their genes and they seem to have developed a mind more of a prey animal then that of a predator.

TOOMEY: Rogers has even gotten to the point where he can place a radio collar on an acclimated black bear without tranquilizers, using only a can of condensed milk as a distraction. Rogers is quick to warn that touching a bear is usually one of the quickest ways to get bitten or slapped and that his acclimated bears still maintain their fear of other humans, even when he's with them.

[FOOTSTEPS THROUGH THE WOODS]

TOOMEY: Back in the forest, the group has come across more proof that they’re on the right trail.

ROGERS: Hey, look here. What’s it made out of?

TOOMEY: It’s bear poop. Or scat, as its known in the business.

ROGERS: I’m not gonna ask anybody to taste this scat, but I would like to have everybody smell it. I say bears are such wonderful animals that their scat doesn’t even stink.

[LAUGHTER]

TOOMEY: Rogers pulls the scat apart and finds lots of beechnut hulls. He says under normal conditions, bears prefer that kind of natural food to things like backyard grills or dog chow. But there's research that disputes that. And Rogers has garnered criticism for his research techniques as well. Some say because they're habituated to his presence, his bears are less likely to fear other people, placing both animal and human in jeopardy.

[BEAR MOAN]

TOOMEY: This haunting sound is being made by a black bear. Some people have described it as a growl.

ROGERS: Because if a person is afraid of an animal, any sound they make will be interpreted as a growl.

[BEAR MOANING]

ROGERS: But it’s just their moan of fear. The bear’s sitting up in a tree in abject terror.

[BEAR MOANING; CHOMPING AND CHEWING]

ROGERS: You also hear this blowing and chomping. [LOUD BLOW] They blow and then clack their teeth together. Just means the bear is scared.

[TEETH CLACKING]

TOOMEY: And then there’s this scenario:

ROGERS: A mother at the base of a tree. Cubs are up the tree. Somebody comes near. The bear gathers itself. Lunges forward. Slams its feet down hard. Makes the ground shake and goes WHHHHHOOOOOOOO!.

[WHHHHHOOOOOOOO SOUND]

ROGERS: People interpret it as an aggressive bear. It means the bear is nervous. It’s no more threatening than when a deer stomps its hoof and snorts.

TOOMEY: Rogers says in 35 years of research he’s never heard a bear growl or had one try to attack him.

[FOOTSTEPS IN THE WOODS]

MCCARTER: This is the end of the trail.

ROGERS: Ho, ho, ho.

TOOMEY: At the base of a red maple tree, the group spots a bear-size depression in the leaf litter.

[RUSTLING LEAVES; INQUISITIVE CHATTER GROUP]

MCCARTER: This is the bed, at the base of the tree between these logs. No tracks leading out except to defecate.

ROGERS: Look at all this sign of where it laid on that log and kind of squashed down snow.

TOOMEY: Most researchers agree that black bears pose less of a danger than a lot of people realize. But Rogers has chosen to take that message out on the road, to become an advocate for the animal at a time when black bears and people are increasingly entering each others’ territories. Perhaps, for Rogers, it’s his way of showing gratitude.

ROGERS: I never thought I’d have the privilege of walking right next to a bear and viewing the forest through the bear’s reactions. What it’s focusing its ears on, what it’s looking at, what it’s sniffing on the forest floor. It just opened my eyes to a new view of the forest.

TOOMEY: Rogers is currently following seven radio-collared bears near his home base in Ely, Minnesota. And he’s working to establish a bear education center there as well. Rogers says bears can co-exist with us. The question for him is, are we willing to co-exist with them? For Living on Earth, I’m Diane Toomey in Charlemont, Massachusetts.

ROGERS: Someone’s been sleeping in my bed and it’s all messed up!

MAN: Talk about evil, Goldilocks was the evil one.

ROGERS: Yeah!

MAN: Took advantage of these poor bears who had a beautiful home, beautiful beds, lots of food…

For a black bear slideshow click here.

Listen to some bear vocalizations:

– clicks

– coos

– crying

– grunts

– gurgle

– huffing

– moan

– nursing

– scream

Related links:

- Wildlife Research Institute

- North American Bear Center

Thawing Scents

CURWOOD: The poet Robert Lowell once wrote that you can tell when it’s skunk hour because the little critters “march on their soles up Main Street: white stripes, moonstruck eyes' red fire.” Commentator Verlyn Klinkenborg says he knows skunk hour best – when he smells it.

KLINKENBORG: You don’t really notice a skunk’s smell. It notices you. It loiters in the air, nearly sentient, waiting to knock you down, strong enough to make you wonder how a skunk can smell anything but itself. I walked into a fresh scent on my way to the barn one morning a couple of weeks ago. A skunk could have been probing the wire around the chicken-yard, but there were no signs of digging in the snow. It might have been testing the duck-pen, but there were no tracks there either.

In the warmth of that afternoon I heard the sound of bees, and then I saw where the sound was coming from. The skunk had attacked a corner of one of the hives in the night. Its claws hadn’t done much damage, only enough to open a crack which the bees were trying to patch up with propolis. The month was still too cold for them. They wouldn’t have been out without the skunk’s provocation. But there was the answer to one of winter’s most pressing questions: are the bees still strong in the hive?

A farm is naturally a place of bold scents, though most of them seem to have been bottled up by the sharp cold of this past winter. A thaw releases them. Early spring suddenly smells like a very old barnyard. It hits me how long it’s been since I last cleaned the hen-house. But the real sign of the thaw we’ve been having is the skunks. They begin to come out into the margins of daylight in the same week the highways start to heave with frost. To drive around here is to feel your way along a lurching roadway from one slick of skunk-scent to the next. Sometimes I pass a skunk just changing its mind at the edge of my headlights. More often, I see those that kept right on going and didn’t make it. They leave in the air an immortality all their own.

That evening, I knocked together the corner of the hive that had been clawed apart. A couple of bees spurted out and droned around my head. But they weren’t entirely serious. I’ve heard that a skunk will disturb a hive not to get at the honey but to eat the bees that mob him. I’ve also heard that a skunk’s smell can travel well more than a mile downwind.

They say, in fact, that skunks in winter don’t really hibernate. They den up, five or six females with one male, and sleep deeply through the cold weather. The least thaw rouses them to hunger and desire. They stir from their nests and amble down to the road, as if drawn there by something only skunks can know. They wait in the night, trying to decide if the highway selects for boldness or hesitation.

CURWOOD: Verlyn Klinkenborg writes about the rural life for the New York Times and is a frequent contributor to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Loudon Wainright III “Dead Skunk” ALBUM III (Columbia/Legacy – 1972)]

CURWOOD: You can hear our program any time on our Web site. The address is livingonearth.org, that’s livingonearth.org. You can reach us at comments@loe.org. Once again, comments@loe.org. Our postal address is 20 Holland Street, Somerville, Massachusetts, 02144. And you can call our listener line at (800) 218-9988. That’s (800) 218-9988.

CURWOOD: And for this week, that's Living on Earth. Next week – The U.S. Supreme Court is about to step into the fight over Vice President Cheney's Energy Task Force. Environmentalists are suing for access to task force records, and they are finding some unexpected allies.

FITTON: I personally am pretty conservative on environmental issues. I would like to see the Alaska wilderness further open to oil development. Heck, I’d like to see an oil derrick here in the Potomac, if necessary.

CURWOOD: That’s Tom Fitton of Judicial Watch – one of Washington's most conservative groups – and he agrees that the Bush administration should come clean about how its energy policy was crafted.

FITTON: You know, I may have voted for Dick Cheney, or I may have voted for George Bush, but I consider it kind of like being the cop who pulls over the mayor. I voted for you Mr. Mayor, now here’s your ticket, show up in court. This is the equivalent here.

CURWOOD: The vice president and his energy policy, next time on Living on Earth. And between now and then you can hear us anytime and get the stories behind the news by going to livingonearth.org. That’s livingonearth.org.

[ CHIRPS AND WHISTLES]

CURWOOD: We leave you with an audio clue that spring has arrived for us northerners. Chris Watson recorded this nightingale in Cambridgeshire, England where the bird has come to breed after its annual migration from its winter home in West Africa.

[EARTH EAR: Chris Watson “ Bedfordshire/Cambridgeshire Border” NIGHTINGALES: A CELEBRATION (British Trust for Ornithology)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced for the World Media Foundation by Chris Ballman, Eileen Bolinsky, Jennifer Chu, Cynthia Graber, Ingrid Lobet, and Jeff Young. Our story on Green Accounting was produced by Gernot Wagner.You can find us at livingonearth.org.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes form the National Science Foundation, supporting coverage of emerging science; and Stonyfield Farm – organic yogurt, cultured soy, and smoothies. Ten percent of their profits are donated to support environmental causes and family farms. Learn more at Stonyfield.com. Support also comes from NPR member stations, the Ford Foundation, for reporting on U.S. environment and development issues, and the Wellborn Ecology Fund.

ANNOUNCER: This is NPR, National Public Radio.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth