Walking with Bears

Air Date: Week of April 9, 2004

Thanks to a burgeoning black bear population in the U.S., there are more and more encounters between those animals and humans. But researcher Lynn Rogers says only rarely is there anything to fear. Diane Toomey went on a walk in the woods with the bear scientist.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood and coming up: the first breath – or sniff? – of spring. But first: black bears. They are coming back in earnest in the eastern United States. Where I live – about an hour outside of Boston – a mother bear and her cub were spotted just down the road a piece.

And last fall in New Jersey there were so many black bears the state held its first bear hunt in more than three decades. Bear and human interactions are way up in many parts of the country, ranging from backyard encounters to bears entering homes to raid kitchens. And one researcher says any problems lay with the attitudes of humans. Diane Toomey has this profile of bear scientist Lynn Rogers.

TOOMEY: It’s a chilly morning on the Massachusetts side of the Berkshire mountains. About a dozen people are gathered here today, in black bear country, in the hopes of tracking a bear.

MAN: I’m here to meet people who like bears and to learn something.

TOOMEY: But even among this crowd, there’s a bit of trepidation. This woman recently had a close encounter with a bear right outside her front glass door.

WOMAN: I was face to face with this bear looking in. [LAUGHTER] And that really scared me. But I love the bears and I’m trying to work through that experience! [LAUGHTER]

TOOMEY: For that kind of fear, there’s no better therapist than wildlife biologist Lynn Rogers.

[FOOTSTEPS IN THE WOODS]

ROGERS: When a bear shows up in somebody’s yard, whether that’s a nuisance or a joy depends on the person’s attitude.

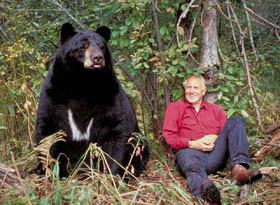

Dr. Lynn Rogers

Dr. Lynn Rogers

TOOMEY: Sixty-four-year-old Lynn Rogers, six feet tall with shoulders to match, looks like, you guessed it, a bear. He even sounds a bit like Smokey, that most famous of black bears. And when the group picks up the trail of a bear, and Rogers stops to investigate, you’ll see he shares some of the animal’s tastes.

ROGERS: Here's one the bear missed. Hmm. I like nuts and berries. This is a beechnut. Really good! Bears are no dummies.

[LAUGHTER]

TOOMEY: Rogers began his research 35 years ago in northern Minnesota, studying basic bear biology. He was the first researcher to draw blood from wild hibernating bears and did pioneering work in describing the matriarchal nature of bear society in which mothers bequeath part of their territory to daughters.

His research, using radio telemetry to follow as many as four generations of family groups, has been praised by E.O. Wilson as one of the greatest wildlife studies of all time. But Rogers eventually turned to, what he describes as, the least studied area of bear biology – the bear/human interface.

ROGERS: There’s people making a living trying to scare us about bears. Telling and re-telling the stories of killings by bears. But there’s only been 52 killings by black bears in the last 100 years across North America.

TOOMEY: So for every human killed by a black bear, Rogers says, 45 are killed by dogs, 120 by bees and hornets, and 60,000 people are killed each year by a fellow human.

ROGERS: That’s why I feel safest walking in the woods right next to a bear!

TOOMEY: With the help of tracker John McCarter, the group is walking through a light dusting of snow in the hopes of backtracking a bear, tracing its movements back in time and moving away from the actual animal. But it’s looks like we’ve gotten too close for comfort.

MCCARTER: And see how the leaves are all scuffed down? The bear stopped abruptly here. And if you look right down there where the bear was facing? That points down to the swamp we were in earlier. And then the bear did a 45-degree turn here, hard and fast, and ran off that way.

ROGERS: It shows just the extent to which bears try to avoid people. Here’s a bear, two, three hundred yards from us. Not only did it avoid us, I mean it ran to get away from us while we were still that far away.

TOOMEY: Rogers’ knowledge of black bears comes from a unique perspective – a distance of about five to 10 yards. It’s a research technique no one else has tried with bears.

ROGERS: After hundreds of hours of trying to get near a bear and get it to accept me, finally I get to the point where I can walk with it, sleep with it, record detailed data as it ignores me. I’m not a friend, I’m not an enemy. I’m not a competitor, I’m not a food giver. I’m just there.

TOOMEY: On these 24-hour walks, Rogers carries no food or water, barely sleeps, and just simply…observes.

ROGERS: And the bears just go about their business of making a living, tearing open logs to get ants, foraging for berries, or hazelnuts, whatever. I learned their vocalizations and body language and how they raise their cubs. I learned what bears are really like.

TOOMEY: While Rogers may acclimate a bear to his presence in one part of the forest, he says that same bear may be spooked by him in another. So to get past this, Rogers often does something that sounds pretty dangerous.

ROGERS: Sometimes you have to wait till they have cubs. Then when the mother is in there with the cubs, that kind of holds her in place, and I can set up a a little office outside that den. With a sleeping bag, a laptop computer, and a cell phone. And they gotta just get used to me being there. And by the time they emerge in the spring, I’m just part of the woodwork.

TOOMEY: Or part of the family, as he puts it. This technique wouldn't be possible with a grizzly bear. That’s because grizzly mothers are hard-wired to protect their cubs. Indeed, 70 percent of grizzly killings are by mothers doing just that. But Rogers says no one has been killed by a black bear defending offspring. He has a theory about why this species has, in his words, come to be ruled by fear.

ROGERS: I think part of it goes back to the Ice Ages, when they were living along such powerful predators as saber tooth cats, American lions, dire wolves (sp). Powerful predators black bears wouldn’t have stood a chance against any of them. But black bears could survive because they were the only one that could climb a tree, and they had this attitude of run first and ask questions later. The timid ones apparently passed on their genes and they seem to have developed a mind more of a prey animal then that of a predator.

TOOMEY: Rogers has even gotten to the point where he can place a radio collar on an acclimated black bear without tranquilizers, using only a can of condensed milk as a distraction. Rogers is quick to warn that touching a bear is usually one of the quickest ways to get bitten or slapped and that his acclimated bears still maintain their fear of other humans, even when he's with them.

[FOOTSTEPS THROUGH THE WOODS]

TOOMEY: Back in the forest, the group has come across more proof that they’re on the right trail.

ROGERS: Hey, look here. What’s it made out of?

TOOMEY: It’s bear poop. Or scat, as its known in the business.

ROGERS: I’m not gonna ask anybody to taste this scat, but I would like to have everybody smell it. I say bears are such wonderful animals that their scat doesn’t even stink.

[LAUGHTER]

TOOMEY: Rogers pulls the scat apart and finds lots of beechnut hulls. He says under normal conditions, bears prefer that kind of natural food to things like backyard grills or dog chow. But there's research that disputes that. And Rogers has garnered criticism for his research techniques as well. Some say because they're habituated to his presence, his bears are less likely to fear other people, placing both animal and human in jeopardy.

[BEAR MOAN]

TOOMEY: This haunting sound is being made by a black bear. Some people have described it as a growl.

ROGERS: Because if a person is afraid of an animal, any sound they make will be interpreted as a growl.

[BEAR MOANING]

ROGERS: But it’s just their moan of fear. The bear’s sitting up in a tree in abject terror.

[BEAR MOANING; CHOMPING AND CHEWING]

ROGERS: You also hear this blowing and chomping. [LOUD BLOW] They blow and then clack their teeth together. Just means the bear is scared.

[TEETH CLACKING]

TOOMEY: And then there’s this scenario:

ROGERS: A mother at the base of a tree. Cubs are up the tree. Somebody comes near. The bear gathers itself. Lunges forward. Slams its feet down hard. Makes the ground shake and goes WHHHHHOOOOOOOO!.

[WHHHHHOOOOOOOO SOUND]

ROGERS: People interpret it as an aggressive bear. It means the bear is nervous. It’s no more threatening than when a deer stomps its hoof and snorts.

TOOMEY: Rogers says in 35 years of research he’s never heard a bear growl or had one try to attack him.

[FOOTSTEPS IN THE WOODS]

MCCARTER: This is the end of the trail.

ROGERS: Ho, ho, ho.

TOOMEY: At the base of a red maple tree, the group spots a bear-size depression in the leaf litter.

[RUSTLING LEAVES; INQUISITIVE CHATTER GROUP]

MCCARTER: This is the bed, at the base of the tree between these logs. No tracks leading out except to defecate.

ROGERS: Look at all this sign of where it laid on that log and kind of squashed down snow.

TOOMEY: Most researchers agree that black bears pose less of a danger than a lot of people realize. But Rogers has chosen to take that message out on the road, to become an advocate for the animal at a time when black bears and people are increasingly entering each others’ territories. Perhaps, for Rogers, it’s his way of showing gratitude.

ROGERS: I never thought I’d have the privilege of walking right next to a bear and viewing the forest through the bear’s reactions. What it’s focusing its ears on, what it’s looking at, what it’s sniffing on the forest floor. It just opened my eyes to a new view of the forest.

TOOMEY: Rogers is currently following seven radio-collared bears near his home base in Ely, Minnesota. And he’s working to establish a bear education center there as well. Rogers says bears can co-exist with us. The question for him is, are we willing to co-exist with them? For Living on Earth, I’m Diane Toomey in Charlemont, Massachusetts.

ROGERS: Someone’s been sleeping in my bed and it’s all messed up!

MAN: Talk about evil, Goldilocks was the evil one.

ROGERS: Yeah!

MAN: Took advantage of these poor bears who had a beautiful home, beautiful beds, lots of food…

For a black bear slideshow click here.

Listen to some bear vocalizations:

– clicks

– coos

– crying

– grunts

– gurgle

– huffing

– moan

– nursing

– scream

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth