A Field Guide to Sprawl

Air Date: Week of October 29, 2004

"Parsley round the pig" may not be a catchphrase for city planners, but it is a term you can find in Dolores Hayden’s new dictionary on sprawl. Host Steve Curwood talks with the author of "A Field Guide to Sprawl" about the many manifestations of sprawl slang.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Phrases like “snout-house” and “parsley round the pig” may sound more like they belong at a county fair than in a city planner’s guide.

But this is typical jargon for builders and real estate developers when it comes to describing the kind of American landscape we’ve come to know as sprawl.

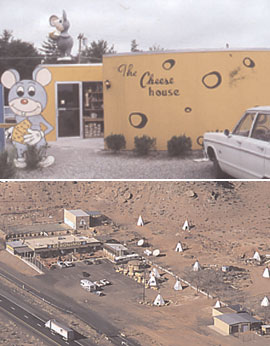

Dolores Hayden teaches architecture at Yale University, and has compiled this slang – along with some of her own choice phrases – in a dictionary of sorts that she’s titled “A Field Guide to Sprawl.” The volume is illustrated with aerial photographs taken by Jim Wark. Dolores Hayden says that citizens armed with her guide will be able to identify tell-tale signs of sprawl in their own neighborhoods. And she joins me now. Welcome to Living on Earth.

HAYDEN: Thank you. I’m delighted to be with you today.

CURWOOD: Now, most field guides that I know are of things that people are particularly interested in looking at, and wanna see, I mean butterflies, birds, plants. But this really isn’t one that you, the author, are thinking that people are going to want to look at out of pleasure.

HAYDEN: I organized this as a devil’s dictionary of bad building patterns. It begins with an alligator, which is an unsuccessful subdivision that isn’t producing any money, and it ends with a zoomburb, which is a place that’s growing at double digits in each census. And in between there are many other terms that seem to pretty much cover what one finds in vernacular American building today across the country.

CURWOOD: Okay, so a zoomburg, you mention. You also have boomburg in here. Now what’s the difference between a zoomburg and a boomburg?

HAYDEN: (LAUGHS) A boomburb is a rapidly growing, urban sized place, that is not in…that is located in the suburbs, that is not a central city. Many of them are in the metro areas of large cities like Phoenix, LA, Denver, Las Vegas. A boomburb is essentially the same thing as a zoomburb. A newspaper in the south was edited by people who heard the word boomburb, and they decided they could go it one better, and that’s where they came up with zoomburb.

CURWOOD: Just tick off two or three of the most famous of these perhaps.

HAYDEN: (LAUGHS) I think the one that’s in the book is Simi Valley, California. But these are not necessarily places that your listeners across the nation will have heard of because they’re not really places. They don’t have urban cores. They often don’t have much public space. They don’t have very many jobs. As opposed to edge cities, or edge nodes, which are places like Tyson’s Corner in Virginia, or Schaumburg outside of Chicago, and your listeners will know those places because they are urban scale in terms of the number of jobs that they have. And, indeed, they usually have more jobs than bedrooms, although they may have a little bit of housing they have substantial jobs.

CURWOOD: Now, let’s see, some other words you have in here…what’s a “toad?”

HAYDEN: Well, a toad is a very unattractive thing to find in the landscape. It is a temporary, obsolete, abandoned or deteriorating building, and this is another planner’s acronym. The example that I give is an abandoned industrial facility in the Midwest. Something that no one has found a new use for, something that’s just simply not working.

CURWOOD: Uh-oh, I think the amphibian anti-defamation league might come after you on that one.

|

|

CURWOOD: Hmm. And a snout-house is a home for a pig? You have snout-house in here. HAYDEN: Ahh, the snout-house has a protruding garage – a two or three car garage that protrudes from the front of a house and pretty much obscures the façade of the house so it’s difficult to find the door. And in the photograph that Jim took, you see a whole row of these lined up and you wonder whether you could get into any of these buildings. They’ve been made to be against the zoning rules. In Portland, Oregon, there was a planner who said that he wanted every house to pass what he called a “trick-or-treat test”. The trick-or-treat test means on Halloween kids can find the door. CURWOOD: Some of the photographs that you have of aerial photography of some of these areas, they’re taken from mostly 2,000 feet in the air. This may sound ironic, Professor Hayden, but some of them look kind of beautiful, really. I mean they have a strong graphic representation, a symmetry… HAYDEN: My favorite is the tire dump. The photograph of the tire dump has so many different shades of black in it; it’s quite a remarkable study in color. At the same time, you can look at this and think about how the United States is a country with 500 million waste tires sitting in various tire dumps across the country and on tire mountains sometimes. So, it’s a part of our landscape that we just need to look at a little harder. And I think if Jim’s photographs encourage people to look a little bit harder, that’s a good thing. CURWOOD: What’s the process that your photographer, Jim Wark, used to take these pictures? HAYDEN: Well, he’s a pilot as well as a photographer. He’s based in Colorado, and they’re generally taken from between 500 and 2,000 feet. They’re oblique angle aerial photos, so that means you can have the façade of the building set into the landscape in a way that shows you both the architecture and the site plan. CURWOOD: In your book you write that aerial photos are used by Wal-mart and McDonald’s. Why? HAYDEN: I think that many corporations looking for development sites, especially in the last 30 or 40 years, have taken to doing aerial surveys of neighborhoods that are growing and changing rapidly as a way to find sites for new big box stores, or new fast food places. And they’re frequently used in combination with geographic information systems. In my book, I am trying to make aerial photography available to activists and citizens groups who may be opposing developers’ suggestions about new big box stores, new fast food, new subdivisions. I want this technology to be available to both sides. CURWOOD: To what extent do you think that sprawl was born of speculation? That is, builders who would get some money together, get some space to put up buildings, without a customer already signing on the dotted line? HAYDEN: Well, in the 1920s, Herbert Hoover was secretary of commerce before he became president. And at the Department of Commerce he worked very closely with people in the real estate industry to find ways to stimulate real estate development, and to promote employment through construction jobs. He created over 7,000 local growth machines through an allied non-profit called Better Homes in America, Inc. They drafted a good deal of legislation, some of which eventually became the FHA, insured mortgages, which meant that banks would advance a developer 90 percent of what he needed to produce a subdivision without having anybody sign on the dotted line. After that, there were additional subsidies for real estate developers. In 1954, tax legislation created accelerated depreciation for Greenfield commercial real estate. And this is where the malls begin to thrive. It’s very hard to have a mall that doesn’t make money because of the way that taxes are structured – you don’t have to sell the goods to make money, you just have to write them all off in seven years.

CURWOOD: Now, you say that federal government encourages sprawl from the homeowner’s side by something you call a “mansion subsidy.” HAYDEN (LAUGHS): The mansion subsidy, that’s right. Well… CURWOOD: Can you explain what you mean by this? HAYDEN: We have a very strong subsidy for houses getting bigger and bigger all the time, and this is what’s called a mansion subsidy. Basically, anyone who buys a house can subtract the mortgage interest plus the points in the property taxes from their taxable income every year. And this is possible on not just one house, but up to two houses, and the total principle can be one million dollars a year. That is really a subsidy for people at the wrong end of the economic spectrum. We need to send our housing subsidies to people who need affordable housing, modest houses. That mansion subsidy ought to be capped at the price of a modest house. CURWOOD: Which is how much these days? HAYDEN: I think it depends a little bit on where you are. But it definitely isn’t a million dollars. CURWOOD: Now, why is there relatively little sprawl in Europe? HAYDEN: I think the Europeans have stronger land use control. They have better greenbelts, they have more barriers and growth boundaries, and much stronger historic preservation legislation. But that said, there is sprawl in Europe. If you go to the outskirts of many beautifully preserved, older towns or cities, you do find the big boxes, the fast food, and the tag farms. Many of the same things that one finds in the United States are there, sometimes camouflaged a little more effectively. And it will frequently be American corporations who are heading the planning projects and building projects that are there in Europe. It is a global thing. CURWOOD: Delores, your book is called “A Field Guide to Sprawl.” If you were writing a book called “A Field Guide to Anti-Sprawl, where would you take a picture? HAYDEN: Oh, there are many communities that I have found very fascinating, but a project that I would point to right away is down in Westchester County. There was an abandoned factory there which was really a toad. And a group of people decided they would convert it into a new public library for the town on the ground floor, and affordable housing on the two upper floors, with special priority given to firefighters and teachers working in that town. It’s right across the street from a railroad station and it anchors part of an older business district. And that’s the sort of project that knits together pieces of an existing town and makes everything a little bit stronger. CURWOOD: Delores Hayden is a professor of architecture and American Studies at Yale University, and author of the book, “A Field Guide to Sprawl.” Thanks for taking this time with me today. HAYDEN: Thank you, I enjoyed it. [MUSIC: Ry Cooder “Nothing Out There” PARIS, TEXAS ORIGINAL MOTION PICTURE SOUNDTRACK (Warner Brothers – 1985)] Links

|

“Asphalt nation” is the paved-over United States. (Photo: Jim Wark ©, “A Field Guide to Sprawl,” W.W. Norton & Co.)

“Asphalt nation” is the paved-over United States. (Photo: Jim Wark ©, “A Field Guide to Sprawl,” W.W. Norton & Co.)