October 29, 2004

Air Date: October 29, 2004

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Toxic Sweets

View the page for this story

What started as a routine look at lead poisoning from old paint at the Orange County Register turned into a two-year investigation of lead poisoning from Mexican candy. The investigation focused attention on a little known problem and is already leading to change. Host Steve Curwood talks with the two journalists from the Register who uncovered the story. (12:30)

CO2 Spike Leaves Scientists Concerned

View the page for this story

A study out of Mauna Loa Laboratory reveals a dramatic jump in atmospheric levels of carbon dioxide in the last two years. Host Steve Curwood talks with David Schimel, senior scientist with the National Centers for Atmospheric Research, about the possible explanations for this spike. (06:30)

Listener Letters

View the page for this story

We dip into the Living on Earth mailbag to hear what listeners have to say. (02:30)

Beetle Mania

/ Paul InglesView the page for this story

A sound artist in New Mexico has devised a unique way to save drought-ridden piñon trees from falling under attack from the bark beetle. David Dunn listens to the tree to see if it's infested. Paul Ingles reports. (08:00)

Environmental Health Note/Now Hear This!

/ Jennifer ChuView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Jennifer Chu reports on a new discovery that explains how we translate sound waves to the brain. (01:20)

A Field Guide to Sprawl

View the page for this story

"Parsley round the pig" may not be a catchphrase for city planners, but it is a term you can find in Dolores Hayden’s new dictionary on sprawl. Host Steve Curwood talks with the author of "A Field Guide to Sprawl" about the many manifestations of sprawl slang. (12:00)

Buzz

/ Josie GlausiuszView the page for this story

Josie Glausiusz, author of "Buzz, the Intimate Bond between Humans and Insects," tells all you need to know about one of our most intimate insect partners – bedbugs. (03:30)

This week's EarthEar selection

listen /

download

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve CurwoodGUESTS: Jennifer McKim, Valeria Godines, David Schimel, Delores Hayden, Josie GlausiuszREPORTER: Paul InglesNOTE: Jennifer Chu

[THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: From NPR, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. There are some candies that are all trick and no treat, and you won’t want your family to have ‘em this Halloween or ever. They’re the popular sweets made in Mexico that feature a touch of tartness and a lot of chili. But all too often the ground chili comes contaminated with lead.

GODINES: I was talking to one of the workers and I said, “I’m just curious about the kind of impurities that might come in these [chili] bags.” And he kind of laughed, he’s like, “Oh, I’ll show you impurities.” And he came back and showed me a car battery part.

CURWOOD: Also, with piñon trees under attack in the Southwest, a sound artist turns bark beetle detective.

HARRILL: We can go out, insert a probe, listen for the presence of the beetle and tell the property owner that this tree is, or this tree is not, infected. That can help them make the decisions on which ones to spray.

CURWOOD: We’ll have those stories and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NPR NEWSCAST]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the National Science Foundation and Stonyfield Farm.

Toxic Sweets

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios in Somerville, Massachusetts, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

It’s that candy time of year. The time when kids put on costumes and knock on doors to load up with the sweet stuff of Halloween. But you don’t want them to bring back home some of the popular candies that are imported from Mexico. The problem surfaced in South California. That’s where a team of journalists from the Orange County Register found dangerous amounts of lead in some candies from south of the border.

The newspaper reported that a child in Orange County is as likely to get lead poisoning from tainted Mexican candy as from eating chips of lead paint. The Register traced the lead in sweets back to the production of chili deep inside Mexico. With me to talk about their investigation are journalists Jennifer McKim and Valeria Godines. Welcome to you both.

MCKIM: Hi, Steve.

GODINES: Hi.

CURWOOD: Jennifer, let me start with you. Now, we should say first that some of these are very, very popular candies that generations of Mexicans and Mexican Americans have grown up on, and they’re sold pretty widely in the United States wherever Mexican goods are sold. And you found out that the state of California and the federal government knew that there were problematic amounts of lead in some candies and were doing little about it. But what got you involved in this story in the first place?

MCKIM: We were interested in the issue of lead poisoning in Orange County because of another story had brought up this issue, so we went to this county healthcare agency. We wanted to find out what was the problem. We asked them for their documents of investigations into the homes of children who have lead poisoning. When a child is found with high lead levels they go to their home and look for sources. And when we got those documents what surprised us was that many of these children were getting poisoned by lead in candy.

So that was brought the story to us. And at that point we started requesting public records from the state and the feds asking for their information. And when we got the records from the state and federal government, we were surprised to see that they had known about this for ten years and that there were hundreds of tests of high levels of candy which they had found many times in the homes of lead poisoned children. And yet, in most cases, they weren’t telling neither public health officials, children, parents, or even Mexican officials or the companies that they were finding these problems.

![]()

MCKIM: It’s a significant amount of lead. We found that in 80 percent of the cases of high tests that eating just one piece of candy would exceed the amount of lead that the FDA thinks is safe for a child to eat in one day. So, if you eat over time you can really raise your blood lead level, and, as you know, Steve, lead poisoning even in low levels can affect a child’s ability to learn. They can have behavioral problems, so even at low levels it’s a significant problem.

CURWOOD: To what extent did the authorities who were discovering this report it to the public and warn people?

MCKIM: When we started reporting this, I think there’d been six public health warnings over a period of ten years and they’d had scores of other candies that had tested high over periods of time, which they hadn’t. So they had told a little bit, but not a lot. And we asked about that clearly, and said “why aren’t you telling people?” And through the emails and through interviews we found out several things.

One is that just part of the issue with these candies is you can test one candy in a batch and it will test high, and then the next will test low, so it’s not homogeneous, the testing. And some of the public health officials said they couldn’t go and warn people about a candy that only tested one out of ten times high in lead; they were concerned about liability. We found in the emails and interviews that they were concerned that they’d get sued by these companies if they warned people. We had public health nurses calling and saying “is this candy dangerous?” And they wouldn’t even give them the information they had.

CURWOOD: And I guess your newspaper, the Orange County Register, went to the trouble of testing candy samples yourself. So, what did you find?

MCKIM: We tested about 180 samples of candies and wrappers. The problems are both in the candies and the wrappers, and found about 32 percent of brands tested high. We also did extensive database work with the federal and state candy testing over years, and found about a quarter of their tests also were high.

CURWOOD: So, what of these high samples was high enough to elevate a child’s blood lead level to pass to safe limits?

MCKIM: If you have a candy that’s point two parts per million, which is the lowest level that they’d really been testing at, and it’s a regular size candy bar, if you ate that that could equal six micrograms of lead which, if you ate over time, would raise your lead level.

Again, they don’t have any testing for lead that if you eat one piece of anything it will raise your blood level. But eaten over time, they show that if you eat that much candy it will go up. Within a 30 day period your blood lead level could go to dangerous levels.

CURWOOD: And 30 days is enough to do a lifetime of damage?

MCKIM: Lead poisoning is irreversible, it doesn’t go away. So, yes, it can cause problems that never go away.

CURWOOD: The big question, obviously then, here is how on earth does lead get introduced into candy? Valeria Godines, can you help me here?

GODINES: Sure, yeah, that’s an excellent question. One thing during our reporting that we kept hearing from officials on the U.S. side of the border is that they suspected that chili, which is a main ingredient, milk chili - a main ingredient in a lot of these candies - was a problem. But there weren’t any conclusive comprehensive tests that they did so we were sort of at a crossroads and we wanted to find out the source of this poisoning and decided we would go find out ourselves.

And what that entailed was us tracing the trail of candy backwards, all the way down to the farms where this chili is grown. We tested everything from the well water to the soil in these chili farms to actually the fresh chilis off the fields, and followed the process all along the way until the chili was actually ground up.

CURWOOD: And where is the lead?

GODINES: We found from our tests in Zacatecas, we found that it actually wasn’t in the water, wasn’t actually coming fresh from the fields. What we found it was in the milling process. Somewhere between the drying process and the milling process lead is getting in. It’s really quite fascinating to see the way it happened because, you know, in the fields, fruits and vegetables generally don’t take up lead from the soil. I didn’t know that at the time, so we were submitting these tests of fresh peppers and they kept coming back negative, so we said “okay, we know that’s not it.”

Then we followed it to the next step, which is drying. And there are various drying facilities where they take them and dry them over 30, usually 34, 36-hour period, and then they lay them out on the ground. So we took some samples from several driers there, we began to see a problem with lead there. We began to get some hits there. It’s somewhat, a little bit of a dirty process; a lot of it’s laid out in the ground as they’re packing them up in various bags, you know men get in and stomp and it with their boots and whatnot.

So I then followed it from the driers to the chili mills, and what we saw was that in many cases, the chili is not washed before it’s milled. Something that was really startling that we discovered is that these chili farmers – when they sell them to the millers, it’s paid by weight. And so there’s a real incentive for them to weigh their bags down.

CURWOOD: Oh….so, what did you find in those bags?

GODINES: (LAUGHS) Well it was interesting because I was spending some time at a mill and I was talking to one of the workers and I said “I’m just curious about the kind of impurities that might come in these bags.” And he kind of laughed, he’s like, “Oh, I’ll show you impurities.” And he came back and showed me a car battery part…nails, rocks. They told me about, you know, they’ve found hammer coming out of these bags, and all sorts of things. And I asked him how…what he told me is that eight out of ten bags that went to that mill contained junk.

And then the dirt actually, too, since a lot of these chilis were not washed, the dirt clinging to these, you know, we think that that’s also another source.

CURWOOD: What happened if the chilis were washed then?

GODINES: We think, and from various lead experts, that that would reduce it by quite a bit. You know, there’s still these other ways – sometimes a lot of them use these really old milling equipment that might be lead soldered, and then over time it grinds itself up and can get in that way. So, there are different ways aside from the dirt, but I really think by doing a thorough washing, that that really could help.

And I should stress. too, because someone may be wondering, “well, maybe you just picked up a bad batch.” We went to four different Mexican states. We went to Michoacan, Zacatecas, Aguascalientes, and Jalisco, and went to the major, major agricultural markets over different periods and bought milled chili from these, and in almost all cases they had lead.

CURWOOD: Now, I understand that your paper, the Orange County Register, has printed up posters of all the candy that tested high for lead, and I’ve got a copy here. It’s both in Spanish and in English, it’s got a little chart showing what lead can do to you and how to avoid it, both in candy and in other sources. What has happened since your investigation?

MCKIM: That poster has been very popular. We printed up 370,000 copies that went out with our story, but since then we had requests from public health officials, public nurses, schools across the country from Virginia to Seattle asking for copies of that poster. We printed up 50,000 more copies to distribute and ran out. We also had the Los Angeles school district request permission to print them out; they printed out about a million copies to send out to their schools and their students.

I think candy manufacturers have seen their businesses drop, and they’ve been doing internal scrutiny to see where lead gets into the product. There’s also been a whole lot of government action since we started the project. A couple weeks before we ran the story, the U.S. FDA sent out a statement saying they were aware that there was problems with lead in candies, and that it would be prudent for kids not to eat certain candies with chili and tamarind in them, and also certain seasonings that kids eat as candy.

Since the story ran, the State Attorney General filed a lawsuit against 33 different companies trying to get the lead out. The U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission issued a ban on companies bringing in candies with high lead in their wrappers. State health departments from New York City, Chicago, Milwaukee, Nevada have all done their own testing and found some lead in certain things and also sent out health warnings on these candies. So there’s been a lot of action, which has been very gratifying.

The fact is these candies are still very available on the street still and we can’t be sure, at this point, that they’re much better than they were before. So there’s still a lot of people out there working on this issue at this point.

CURWOOD: Before we go, I have to ask you something. I have some ground chili in my kitchen that I use on things. Should I be getting that tested?

GODINES: Yeah, that’s a good question. When we were working on this and started to get positive hits on the chili, we all looked at each other and thought “oh my God” – our salsa, our pico de gallo, and things like that. So, in addition to the milled chili, we tested 25 U.S. and Mexican products made with chili: salsa, cooking seasoning, picante sauce, things like that. And what we found actually was almost none of those had any problems. There was one that had point two parts per million at the lower end of the scale.

CURWOOD: I want to thank you both. Jenifer McKim is a reporter, and Valeria Godines is an editor of the Orange County Register in Orange County, California. Thank you for taking this time with me today.

GODINES: Thank you.

MCKIM: Thank you very much.

[MUSIC: Los Lobos “Flor de Huevo” PUTOMAYO PRESENTS: MEXICO (Putomayo – 2001)]

CURWOOD: Coming up: a sudden uptick in the gases that are warming the earth has scientists concerned. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Buddy Emmons “Four Wheel Drive” AMAZING STEEL GUITAR: THE BUDDY EMMONS COLLECTION (Razor & Tie – 1997)]

Related links:

- The Orange County Register’s six part investigative series “Toxic Treats”

- Toxic Treats Index

CO2 Spike Leaves Scientists Concerned

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Science tells us the more greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide that are released into the atmosphere, the warmer the planet will become. And since the Industrial Revolution and the widespread use of coal, gas and oil, the average temperature of the planet has risen by a degree, and CO2 has reached levels unmatched for hundreds of thousands of years.

Now, data from the Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii show a sharp spike in the rate of increase of carbon dioxide over the last two years. Scientists say this jump in the rate of growth of CO2 levels could mean that we face a dramatically shortened timetable for addressing global warming. Joining me now is David Schimel, senior scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado. David, welcome to Living on Earth.

SCHIMEL: Thank you very much.

CURWOOD: We know that carbon dioxide levels have been rising for some years now. What’s different now?

SCHIMEL: Over the past decades, the increase in carbon dioxide has been roughly constant, somewhat paralleling the emissions from fossil fuel and other processes. The last two years have been very high growth rates of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Two consecutive years is a little bit unusual. The really unusual thing is that they’re not associated with any obvious climactic event that might trigger, say, widespread drought or unusually extensive wildfires.

CURWOOD: What are the possible explanations for this rather dramatic jump over the last two years in the amount of carbon dioxide coming into the atmosphere?

SCHIMEL: The first explanation is the scary one, which is that the steady warming that’s been occurring in the past few decades is somehow triggering a release of carbon from certain types of ecosystems: forests, or northern peatlands, or other types of ecosystems that store large amounts of carbon. And if that were to be the correct explanation, it would be of concern because that’s a feedback; the warmer it gets, potentially the more CO2 is released, contributing a fraction to the warming and then possibly releasing more carbon.

CURWOOD: So, in other words, carbon comes out of what, trees, or stuff on the (inaudible)…

SCHIMEL: Trees, soils, in the Arctic we’ve got many systems that have huge amounts of stored carbon in their soils. The soils are really just old, dead plant material, preserved there because of cold and wet conditions.

CURWOOD: Tell me about the not-so-scary explanation.

SCHIMEL: Ah, good. The not-so-scary explanation is a little bit more complicated. We believe that one of the reasons that ecosystems, forests and other types of systems, are taking up carbon now, in the 1990s and 2000s, is because there was a very large amount of forest harvesting in the U.S., in Europe, and parts of Asia between, say, 1850 and 1950. And there are large areas of re-growing forests in areas that were abandoned from agriculture and areas that were harvested, for example in the U.S. during the mining and railroad building eras in the West. And those re-growing forests take up carbon. And the young forests take it up quite rapidly; as they age they begin to take up less and less carbon. They approach a maximum size, if you will.

And it’s possible that what we’re seeing is the beginning of a turnaround in that process where all of these forests that were abandoned over the past hundred, 150 years, are beginning to mature. Now if that’s true, that’s not a good thing, we’d like to see those forests continuing to take up carbon, but it’s not a feedback cycle with warming, per se.

CURWOOD: Two years of data, looking at this increase, is obviously a very short period of time, probably too early to really tell what’s causing this jump, but at what point do you think we might be able to know if this increase in carbon dioxide is a pattern?

SCHIMEL: Well, you’ve asked the hardest question: when will we know something we don’t know now? The simple answer is if this were to continue for two to three more years, it would really be unprecedented and it would be a very conclusive result.

CURWOOD: So, at this point, it could still be a statistical fluke then?

SCHIMEL: That’s correct. And, in fact, it could be unusual conditions in the oceans and not associated with the biosphere at all, although that’s a much less likely explanation.

CURWOOD: For the sake of discussion, assuming that this increase is sustained, that we see it not for just two years, but for three, or five, or six years, how serious is this problem?

SCHIMEL: Well, it’s not going to cause the world to end any time soon. It’s certainly not leading us into a “Day After Tomorrow” scenario ten times faster than the situation that we’ve been observing over the past few decades. But it does mean that we have less time to develop new technology to implement hydrogen, solar, other alternative energies than we would otherwise.

CURWOOD: So, given these concerns, how long can we afford to wait to know for sure that this is a long-term problem? What point should we decide that it is or isn’t?

SCHIMEL: Well, if the increase in the atmosphere continues, that’s an observable fact and we’ll know it’s occurring. Federal agencies in the U.S., university groups and other nations measure this quantity with great care and precision. So, we’ll know the fact of whether it’s increasing, whether this increase is continuing, quite soon.

CURWOOD: David Schimel is a senior scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado. Thanks for taking this time.

SCHIMEL: Thanks, Steve.

Listener Letters

CURWOOD: Time now for your comments from you, our listeners.

[LETTERS THEME UP; FADES UNDER AND OUT]

CURWOOD: Our mailbox was stuffed this week with responses to our recent story about the unhealthy and dangerous conditions suffered by marine mammals at some sea parks. Some listeners said that by focusing on reports of animal abuse at parks without examining the case for non-capture, we were thinking too much inside the box.

“I wish there had been more commentary on the fact that marine mammals suffer horribly in captivity, not just physically, but socially,” writes Maggie Rufo, who listens to Living on Earth on KQED in San Francisco. Ms. Rufo was also disturbed by our interview with a former whale hunter who profited by capturing sea stars. “Rarely have I had a physical reaction to something on the radio,” she writes, “but I actually felt my stomach hurt while I listened to this man.”

Marilee Menard, executive director for the Alliance of Marine Mammal Parks and Aquariums, had a different take. She defends the care of animals at accredited marine parks and says park-based scientific research has filled critical gaps in our understanding of various species.

“Much of what we know today about dolphins and whales was learned from animals in marine life parks,” writes Ms.Menard, who hears us in Washington, D.C. “This information not only helps improve quality of life for animals in marine parks, but also helps save many wild dolphins, whales, sea lions and other marine mammals that are stranded, rehabilitated and released back into the wild each year.”

And finally, a correction. We identified Ted Griffin, the former whale collector we talked with, as the founder of the Seattle Aquarium in Washington. But according to Tom Schaefer of the Seattle Aquarium, Mr. Griffin founded the Seattle Marine Aquarium.

“The Seattle Marine Aquarium that opened in 1962 and displayed two killer whales was Ted Griffin’s private enterprise,” writes Mr. Schaefer, who tunes in to Living on Earth on KUOW. “The present Seattle Aquarium opened in 1977 after the closure of Griffin’s aquarium, and is owned and operated by the City of Seattle. The present aquarium has never had whales or dolphins.”

Your comments on our program are always welcome. Call our listener line anytime at 800-218-9988. That's 800-218-99-88. Or write us at 20 Holland Street, Somerville, Massachusetts 02144. Our e-mail address is comments at l-o-e dot org. Once again, comments at l-o-e dot o-r-g. And you can hear our program anytime on our web site, Living on Earth dot org. That's Living on Earth dot o-r-g.

[LETTERS THEME UP AND OUT]

Beetle Mania

CURWOOD: In the drought-stricken desert of northern New Mexico, the once common piñon tree is dying at a rapid rate. The thirsty, weakened trees are falling to an aggressive attack by tiny bark beetles. Some foresters say that there’s little to be done to stop the infestation and that the die-off is actually helping to thin out some areas of forests that are dangerously overgrown. But upset property owners are looking for ways to save their piñons. Producer Paul Ingles met someone in Santa Fe who is offering them help by literally listening to the beetles’ side of the story.

[CRUNCH OF NEEDLES UNDERFOOT]

INGLES: Nancy Dahl walks toward a mostly barren hillside, just a few feet from her southwest-style stucco home on the outskirts of Santa Fe.

[MORE CRUNCHING]

Nancy Dahl kneels by a dead piñon tree. (Photo: Paul Ingles)

INGLES: Dahl says she’s spent thousands of dollars over the last two years having more than 100 dead piñon trees cut down and hauled off to reduce the threat a wild fire might pose to her home.

[HIGHWAY SOUNDS]

INGLES: When she moved here 25 years ago from Michigan, Dahl found a quiet tree-buffered retreat.

[HIGHWAY SOUNDS]

INGLES: Now, the drone of the nearby highway rolls unfettered up this cleared-off hillside, right through the open windows of the home.

[HIGHWAY SOUNDS, BIRDS CHIRPING]

INGLES: Dahl’s view isn’t what it once was either. Across the highway, a hill of undeveloped open space – once a picturesque dense green – is now half brown with wasted piñons. The trees were killed off by the ips confuses bark beetle infestation that started midway through this region’s now four year drought.

DAHL: It’s sad. It’s very, very sad for me. Really, these are my friends. These trees were my friends.

|

|

DUNN: Basically it’s a meat thermometer meets a greeting card. INGLES: A greeting card? DUNN: Some of the best of these piezoelectric transducers actually can be found inside greeting cards, particularly Hallmark make really nice ones that they use as little playback speakers. These little things work as both input and output transducers for sound. INGLES: While Dunn is becoming known for creating unusual devices for recording the quieter sounds of nature, his resume includes classical training as a violinist, composing and performing experimental music and teaching about the properties of sound. But he’s set aside most of that this year for projects that merge his sound gathering skills with the environmental sciences. DUNN: I think it is essential that at this point historically that artists take a role in collaboration with the scientific world – that artists and scientists work together towards real world problem solving. We need all the help we can get. [SOUND OF BARK] INGLES: Like a nurse administering an IV, Dunn gingerly slips the sharp four-inch metal probe at an angle about a half inch into a tree on Nancy Dahl’s lot. DUNN: Like that, and that’s all we do. Then we listen to see if there’s any activity. [WHOOSHING OF NON-INFESTED TREE SOUNDS] INGLES: These Dunn recordings are amplified about six times over so we can hear them. The sounds we hear first are of a non-infested tree. [NON-INFESTED TREE SOUNDS] DUNN: And at this stage there’s virtually nothing. But what you do hear is, of course, is the movement of the tree and the wind and its motion. [NON-INFESTED TREE SOUNDS] INGLES: It’s when one of Dunn’s probes picks up noises like these that he knows a tree is a goner. [OCCASIONAL CLICKING OF BEETLE-INFESTED TREE] DUNN: As soon as the beetles are present, then we hear this characteristic sound [MORE CLICKING OF INFESTED TREE] DUNN: The sound of larvae and adult beetle motion. It’s a simple motion within the interior phloem of the tree. [INFESTED TREE SOUNDS] DUNN: And ips beetles, even though they’re very small, about the size of a small grain of rice, they have a little sound generating organ on the back of their head called a pars striden. And it essentially functions like a gyro, or a percussion instrument that has ridges on it. So they basically can rub this, their middle of their body, against their heads as they move the heads. And they produce sound both intentionally but also, I think, secondarily as just a consequence of motion within the tree. INGLES: A piñon tree, stressed by lack of water, essentially calls the beetles in by emitting a pheromone that signals it’s too weak to fight. If a beetle started to bore into a healthy piñon, the tree would produce sap to fill the hole and force the beetle out. But without water there’s no sap, and soon the beetles are drilling and breeding and making more of a racket. Here’s Dunn’s recording of a moderately infested tree. [FASTER CLICKING OF BEETLE-INFESTED TREE] INGLES: And before long, it sounds like quite a party in a fully infested tree. [LOTS OF CLICKING OF INFESTED TREE] INGLES: Even at this stage the piñon may look healthy on the outside, but the beetles have sentenced it to death by spreading a black stain fungus on the inside that moves down through the tree’s root structure. There it may spread on its own to other adjacent trees, or the beetles may themselves take the fungus to the next tree. But looking at, say, three apparently healthy piñons side by side is a bit like trying to guess which shell has the pea under it in a shell game. HARRILL: From the point of view of the property owner, you’d like to know whether a tree is infected first. INGLES: Bob Harrill is one of two scientists with David Dunn’s non-profit organization, the Art and Science Laboratory. He’s a doctor of chemistry who’s worked in applied environmental science since the late 1960s. Like Dunn, Harrill likes connecting the worlds of art and science to solve practical environmental riddles like, in this case, which tree has the beetles. HARRILL: We can go out, insert a probe, listen for the presence of the beetle and tell the property owner that this tree is, or this tree is not, infected. That can help them make the decisions on which ones to spray. INGLES: And which ones to water, which can also strengthen the tree against the beetle attack. As word of David Dunn’s technique spreads, he’s been asked by more property owners to listen to their trees. He’s happy to help and gather new data, but he says he’s not trying to create a business opportunity. In fact, if clients insist on paying, he suggests a contribution to his non-profit, so he can afford to make even more recordings and design affordable tools to unearth what Bob Harrill thinks may be a rich field of study. HARRILL: There’s been a great deal of research on what’s called the chemical ecology. How chemicals produced by a tree, for example, might attract a particular pest, like a beetle. But we need to explore more about how sound mechanisms might actually contribute to the interactions between insects and plants. INGLES: Whether Harrill and Dunn’s work can find utility beyond helping individual property owners save a few trees is uncertain. But their work has some state officials intrigued. Forest Service agents are open to the possibility that there might be some future role in forest management for the noises David Dunn and Bob Harrill are gathering. For Living on Earth, I’m Paul Ingles, in Santa Fe. [MUSIC: R. Carlos Nakai “Precious Waters” PRECIOUS WATERS RIVER OF LIFE (Narada – 1995)]

Environmental Health Note/Now Hear This!CURWOOD: Just ahead: a field guide to sprawl. First, this Note on Emerging Science from Jennifer Chu. [SCIENCE NOTE THEME] CHU: Now hear this! For years, scientists have puzzled over how sound waves flow through the ear and transform into electrical impulses that can be interpreted by the brain. In other words, how is it we can translate thousands of unique air vibrations into distinguishable sounds, such as the words in this report and the music you hear in the background? Researchers at the University of Virginia say they’ve taken the “mute” button off this mystery. In an article posted on the Internet edition of the journal Nature, the scientists report that they have identified a doughnut-shaped protein located at the tips of sensory hairs in the inner ear that’s key to our ability to hear. In the absence of sound, this doughnut hole is closed. But when sound strikes the protein, the hole pops open and allows potassium and calcium ions to flood the cells of the sensory hairs. The ions carry a positive electrical charge which generates an electrical signal inside the cells. This signal is then relayed to the brain and interpreted as specific sounds. Researchers hope the discovery could lead to new therapies for certain types of deafness in the next ten years. That’s this week’s Note on Emerging Science. I’m Jennifer Chu. CURWOOD: And you’re listening to NPR’s Living on Earth. ANNOUNCER: Support for NPR comes from NPR stations, and: Ford, maker of the Escape Hybrid, a full hybrid S-U-V able to run on electric power alone at certain speeds. For vehicles dot com back slash environment; The Noyce Foundation, dedicated to improving Math and Science instruction from kindergarten through grade 12; The Annenberg Fund for excellence in communications and education; and, The Kellogg Foundation, helping people help themselves by investing in individuals, their families, and their communities. On the web at w-k-k-f dot org. This is NPR -- National Public Radio. [MUSIC: Ry Cooder “Cancion Mixteca” PARIS, TEXAS ORIGINAL MOTION PICTURE SOUNDTRACK (Warner Brothers – 1985)]

A Field Guide to SprawlCURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Phrases like “snout-house” and “parsley round the pig” may sound more like they belong at a county fair than in a city planner’s guide. But this is typical jargon for builders and real estate developers when it comes to describing the kind of American landscape we’ve come to know as sprawl. Dolores Hayden teaches architecture at Yale University, and has compiled this slang – along with some of her own choice phrases – in a dictionary of sorts that she’s titled “A Field Guide to Sprawl.” The volume is illustrated with aerial photographs taken by Jim Wark. Dolores Hayden says that citizens armed with her guide will be able to identify tell-tale signs of sprawl in their own neighborhoods. And she joins me now. Welcome to Living on Earth. HAYDEN: Thank you. I’m delighted to be with you today. CURWOOD: Now, most field guides that I know are of things that people are particularly interested in looking at, and wanna see, I mean butterflies, birds, plants. But this really isn’t one that you, the author, are thinking that people are going to want to look at out of pleasure. HAYDEN: I organized this as a devil’s dictionary of bad building patterns. It begins with an alligator, which is an unsuccessful subdivision that isn’t producing any money, and it ends with a zoomburb, which is a place that’s growing at double digits in each census. And in between there are many other terms that seem to pretty much cover what one finds in vernacular American building today across the country. CURWOOD: Okay, so a zoomburg, you mention. You also have boomburg in here. Now what’s the difference between a zoomburg and a boomburg? HAYDEN: (LAUGHS) A boomburb is a rapidly growing, urban sized place, that is not in…that is located in the suburbs, that is not a central city. Many of them are in the metro areas of large cities like Phoenix, LA, Denver, Las Vegas. A boomburb is essentially the same thing as a zoomburb. A newspaper in the south was edited by people who heard the word boomburb, and they decided they could go it one better, and that’s where they came up with zoomburb. CURWOOD: Just tick off two or three of the most famous of these perhaps. HAYDEN: (LAUGHS) I think the one that’s in the book is Simi Valley, California. But these are not necessarily places that your listeners across the nation will have heard of because they’re not really places. They don’t have urban cores. They often don’t have much public space. They don’t have very many jobs. As opposed to edge cities, or edge nodes, which are places like Tyson’s Corner in Virginia, or Schaumburg outside of Chicago, and your listeners will know those places because they are urban scale in terms of the number of jobs that they have. And, indeed, they usually have more jobs than bedrooms, although they may have a little bit of housing they have substantial jobs. CURWOOD: Now, let’s see, some other words you have in here…what’s a “toad?” HAYDEN: Well, a toad is a very unattractive thing to find in the landscape. It is a temporary, obsolete, abandoned or deteriorating building, and this is another planner’s acronym. The example that I give is an abandoned industrial facility in the Midwest. Something that no one has found a new use for, something that’s just simply not working. CURWOOD: Uh-oh, I think the amphibian anti-defamation league might come after you on that one.

|

David Dunn listens for bark beetles in a piñon tree. (Photo: Paul Ingles)

David Dunn listens for bark beetles in a piñon tree. (Photo: Paul Ingles)

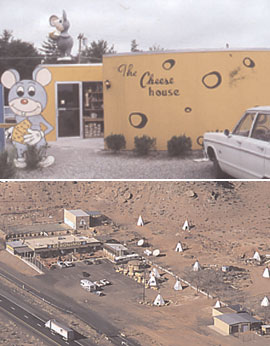

“Asphalt nation” is the paved-over United States. (Photo: Jim Wark ©, “A Field Guide to Sprawl,” W.W. Norton & Co.)

“Asphalt nation” is the paved-over United States. (Photo: Jim Wark ©, “A Field Guide to Sprawl,” W.W. Norton & Co.)  Top: The common bed bug. Bottom: A seven-spotted ladybug larva eats an aphid. (Photos: Volker Steger © “Buzz: The Intimate Bond Between Humans and Insects”)

Top: The common bed bug. Bottom: A seven-spotted ladybug larva eats an aphid. (Photos: Volker Steger © “Buzz: The Intimate Bond Between Humans and Insects”)