Bad News from the Blubber

Air Date: Week of February 15, 2008

(Photo: Ocean Alliance)

Living on Earth’s Bruce Gellerman talks with Dr. Roger Payne and Captain Iain Kerr on board the research vessel Odyssey in Gloucester, Massachusetts. The pair recently completed a five and a half year journey around the world to collect samples of whale blubber to analyze for pollution - and they’re shocked by the results.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Gloucester Harbor—north of Boston—is perhaps best known as a fishing port. It’s also where the 93-foot ketch “Odyssey” is docked. The Odyssey is a unique research vessel. It’s designed to study the behavior and biology of the world’s largest and longest-lived mammals: whales.

Tail of a humpback whale in Alaska. Humpback whales are best known as extraordinary vocalists. Their songs evolve over time and can be heard across oceans. (Photo: Ocean Alliance/Iain Kerr)

[MAN SAYS “AHOY”; MAN SHOUTS; MAN SAYS “…BRING HER IN WHEN YOU’RE READY…” MAN ANSWERS “ALRIGHT”]

GELLERMAN: It was a cold, blustery day, but the seas were calm as I stepped on the deck of the research vessel Odyssey. Captain Iain Kerr lent a hand.

Iain Kerr is Captain of the research vessel Odyssey. (Photo: Ocean Alliance/Chris Johnson)

KERR: Doing good, doing good. You?

GELLERMAN: Fine, thank you.

KERR: It’s not the best of days.

GELLERMAN: Oh, it’s a bit nippy.

KERR: Wee bit nippy.

GELLERMAN: Iain Kerr was born in Scotland and is CEO of the Ocean Alliance. The Odyssey is owned and operated by the non-profit, which was founded by Dr. Roger Payne.

GELLERMAN: Hello, Dr. Payne. How are you?

PAYNE: Very well. Roger is my name by the way.

GELLERMAN: Roger Payne is perhaps best known for his discovery that humpback whales sing songs. Ten and a half million copies of the recording were distributed by National Geographic magazine. It’s still the largest single pressing in the history of the music industry. Roger Payne and Iain Kerr are shipmates from way back.

Dr. Roger Payne has been studying whale acoustics for 40 years. Five and a half years ago he began a round-the-world study to collect baseline data on pollution levels in whales. (Photo: Ocean Alliance/Chris Johnson)

PAYNE: I feel that this effort to figure out how badly polluted the oceans of the world are is in fact the most important thing I’ve ever been involved with scientifically.

GELLERMAN: Why did you get interested in whales?

PAYNE: Well, I started working on sounds of bats, then went to owls, then went to moths, which are all animals for which acoustics are really very important and then I began to think ‘well I’m just entertaining myself. I’m not doing anything that responds to their problems. I could see that we’re taking the world down the drain, basically.’ And then I thought, well if the only thing you know about is the acoustics of animals, what could you do that would matter and then I thought ‘ahh, whales.’

[MUSIC: Roger Payne “Tower Whales” from ‘Songs of the Humpback Whale’ (Living Music 1991)]

PAYNE: That would be it because I knew enough to know they were—had very important acoustic lives.

[WHALE SONG]

PAYNE: But I had never seen a whale. I didn’t know anything about them and the moment I had that idea I realized, okay, I’ll spend the rest of my life doing that.

[WHALE SONG]

GELLERMAN: What do you mean an ‘acoustic animal?’

KERR: Well, I think Roger should talk more to this, but we live in a world of sight. You know, we look around us. Whales live in a world of sound. Often the oceans are dirty, you can’t see more than ten feet. Yet Roger demonstrated that whales could hear sound across oceans. So you need to understand they live in a whole different world to us.

The Odyssey is a 93 foot long steel hulled ketch. (Photo: Ocean Alliance/Iain Kerr)

KERR: But one of the key components of this boat—and it goes back to Roger’s history with the bioacoustics of whales—is we have an acoustic array. A 1,000-foot cable that goes behind the boat. It’s about 100 feet down, and as we’re under way there’s a screen here in front of the helm. You can actually see images of sounds that are being made in the background. And that enables us to track whales 24 hours a day. And it’s really changed the way that we interact with whales and attract whales.

[WHALE SONG]

KERR: And what’s great about this boat is it’s a real tough deep-water boat. It’s got a great, extended offshore capability. Because while we know a lot about the pollution in the Hudson River or the St. Lawrence Seaway, what’s happening in the middle of nowhere. So the whole idea is we needed a boat that would be comfortable for the crew—you know on the old British expeditions you know, you had to have a couple of people die for it to be a successful expedition. We’ve evolved slightly from that now, and the truth is you’re more productive. If people can be comfortable, you can be more productive.

GELLERMAN: You had this five-year expedition. How many whales did you track during that time?

KERR: Well you know, boy, I don’t think I even have an answer for that but I would think thousands. I mean, you need to understand, as we’re going along, we’re recording whales that we interact with every 30 minutes often and the boat ran 24 hours a day. So that’s one of the challenging components about this voyage, is the masses of amount of data we’ve got, and what’s interesting about the data is not necessarily that we’ve been to places that no one’s been before, but we’ve been with a type of technologies, with a type of expertise and skill sets that haven’t been to some of these remotest places on the planet.

The research vessel Odyssey sailing the coast of Hawaii. (Photo: Ocean Alliance/Iain Kerr)

KERR: To get the physical sample from the whale, we like to do a little biopsy So here we just have a quite a simple crossbow—it only cost us like $100, okay, but it does fire a very expensive dart that’s actually made in Finland, and it’s got a little rubber head on it, and when it hits the whale, it bounces and pulls out a very small biopsy about the size of razor head on a pencil.

GELLERMAN: How does it physically work? You pull the string back…

KERR: Well we cock the string back, slide the arrow in—so you have to find a patch of skin. There’s a nice adult spoon whale that is bringing its toxic load down from Antarctica. And you take the biopsy, and the arrow bounces off and then the boat motors up and there’s a person on the bow that scoops the arrow out of the water.

GELLERMAN: Does it hurt the whale?

KERR: Well I don’t think so. You know, the skin of these whales is really tough. I mean, these animals are going down a mile deep. They have really tough skin. I mean, I think one of these arrows—occasionally we fire them and they bounce off. It’s incredible. Had it hit your eye it would have been stuck in three inches. Do you want me to show you?

GELLERMAN: (laughs) No. Thank you, no.

KERR: Okay, so let’s head up onto the bow now, and I’ll show you where we stand when we’re underway and where the biopsy person works from.

[SOUND OF BEING ON BOAT DECK, WALKING TO BOW]

KERR: It will give you a better perspective. You can see these doors are very seaworthy—very heavy. So we’re standing up on the bow now and there’s a pole that sticks out from here 35 feet that we call the whale boom. And what we found was—and just think about it in human nature. If I come up behind you—you know, in the street in the evening, you might be a little nervous. If I’m walking beside you, you know you feel more comfortable—I’m in your periphery. So we found with the whales, rather than coming up behind them, we’d come up alongside of them and then we could be 100 feet from the whale because the boom sticks out 30 feet and then when we took the biopsy, you know—

GELLERMAN: Now this boat is 90 some-odd feet long.

KERR: That’s correct.

GELLERMAN: Whale’s going to be 50-60 feet.

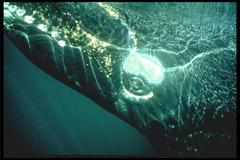

KERR: We’ve been next to blue whales in the Galapagos that was big as the boat. It’s certainly—you understand your place in the wild world when you study whales. You know, we all think it’s all about humanity and yet you get out in the ocean with some of these whales—eyes the size of a grapefruit, little wrinkles, and they’re looking at you saying ‘you know, you’re an intelligent species—look at my lifestyle.

Face to face with a southern right whale in Argentina (Photo: Ocean Alliance/Iain Kerr)

KERR: Yeah.

GELLERMAN: When somebody’s way up on top, do they say, and they see a whale, do they say ‘Thar she blows?’

KERR: They tend to do. You do get caught up in the mystique of the moment. The other favorite one is of course, ‘Land ahoy!’ When you’ve been at sea 36 days with nine people in a tin can, you know, listening to the same music, you know, sometimes you’re very ready to go ashore for some R&R.

[SOUND OF OBJECTS BEING SHUFFLED AROUND]

KERR: So on the wall here, we just have the general screen to show people that when we collect a biopsy we cut it up in from five to seven different parts. So here was our sort of workstation. Obviously we’re at dock right now so we don’t have all the scientific tools lying out.

GELLERMAN: This is your laboratory?

KERR: Well, it is our laboratory. We’re building a larger laboratory back aft in the boat but as soon as you get the samples you want to process them as quickly as you can. So if you think about it, the ocean is what—seven feet from where we are right now. So we collect the biopsy and within seconds sometimes, worst case minutes, we’re processing the samples. And Roger will talk to you more about what we do with each of those components.

PAYNE: We’ve looked at a bunch of samples, but we haven’t looked at all the samples. That remains to be done if we can ever raise the funds necessary to do that. But what we can say is that these animals are polluted beyond your wildest dreams. They are appallingly polluted.

The Odyssey ran 24 hours a day collecting audio recordings and blubber samples from thousands of whales. (Photo: Ocean Alliance/Chris Johnson)

GELLERMAN: Polluted with what?

PAYNE: All sorts of things, including synthetic molecules that human beings make of a huge variety—hundreds of different things. The ocean is downhill of everything on earth, and the result is that everything flows into the ocean from higher ground, and that means it’s the ultimate cesspool basically of the world. Industry has always said, ‘The solution to pollution is dilution’ and it’s absolutely true—if you take some poison and drop it somehow into the ocean or it eventually gets there in streams, it gets diluted down to such low concentrations that in fact, it is harmless. But then a totally insidious thing happens and that is—it dissolves into the oil droplets that are part of the—well they are the base of the food chain and so anything we produce that animals can’t handle they then can’t get rid of and the result is they have to store it and they pass it up foodchains.

KERR: We should talk about too—and maybe if I start this, Roger, and if I do it badly you’ll take it over—we collect this biopsy and we cut it up into pieces, and we get the skin for the genetics, for is it Ian, is it Roger, okay. You’ve then got the blubber, which has got fatty acids in it, which tell us where does it feed on the food chain. You’ve then got the stable isotopes, which tell us roughly where it actually picked up the food that it’s got. And then finally, we’ve got the blubber that we use for the hard contaminant load, and then the skin that we grow the cell lines for, so this tiny little piece of blubber really demonstrates one, that you don’t need to kill whales to learn about them, and two, provides us with, you know, an incredible amount of information about where the animal fed, where it lived, where it fed on the food chain, is it male, is it female.

GELLERMAN: What things are in the ocean, or showing up in these animals, that are causing such problems?

PAYNE: We’re concerned about things like fire retardants. We haven’t done any analysis of those. We don’t know where they stand yet, but hopefully we’ll soon know the answer to that, and we’re interested in the other kinds of things that everybody knows is out in the oceans- things like mercury and other metals and persistent organic pollutants, which is a category so large as to be almost useless, but nevertheless a whole series of molecules which we’re looking at a few of.

(Photo: Ocean Alliance/Chris Johnson)

PAYNE: Many of the substances that we’re concerned with are fantastically insoluble in water. They are highly soluble in fat. So what happens is that they end up in the ocean water, anywhere in parts per trillion or parts per quadrillion, so hugely diluted. But as soon as they get into fats they end up in very, very high concentrations because the fats can hold lots of them. The trouble is the animals don’t have any way of dealing with them so they store them, and then they get passed on when that animal gets eaten by some other animal. So here on your plate is a pound of swordfish. It took a million pounds of diatoms to create that one pound—not the whole fish—just that one pound. A million pounds is 500 tons, so it took 50, ten-ton truckloads of diatoms to make that one pound of swordfish. So you take all those trucks and you park them along a row, it’s about ten blocks long, and to the end of that row you attach your liver and with it you detoxify that entire line of trucks. And that’s what you do when you eat a pound of swordfish. And then maybe tomorrow you have another pound. I adore swordfish. I would do anything to have a piece of swordfish except eat it.

A humpback whale breeches in Argentina.(Photo: Ocean Alliance/Iain Kerr)

PAYNE: And an animal like whales—this is going to get worse and worse and worse from generation to generation, because these substances last so long—so much longer than the lifetimes of these animals, and the result is—I assume—is extinction.

GELLERMAN: What happens now? Where do you go from here?

PAYNE: We are desperately trying to raise the funds necessary to complete the analysis of these compounds. It’s—in the scheme of things—it’s so little money—I mean, it’s less than a million dollars that we need. Once we have the funding necessary to complete the analysis of the samples that we’ve got, we will be able to say, ‘this is how polluted the oceans of the world are with these substances. And the question of why does that matter would be—the answer is very simple. Humanity is about to lose access to fish from the sea, because the fish from the sea are becoming too polluted to be eaten safely.

The Odyssey often comes to within 100 feet of a whale to take a sample of blubber.(Photo: Ocean Alliance/Chris Johnson)

GELLERMAN: I would think that you believe this is the most compelling, important issue of our time, and I’m wondering why it’s so hard to raise money around research like this.

Tail of a right whale at sunset in Argentina.(Photo: Ocean Alliance/Iain Kerr)

GELLERMAN: So this is not an us-against-them problem.

PAYNE: Oh, absolutely not. And those who make it an us-against-them problem ensure that it is an unsolvable problem.

[WHALE SONG]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth’s Bruce Gellerman and producer Bobby Bascomb visited the Odyssey in Gloucester Harbor. Ian Kerr and Roger Payne of the Ocean Alliance use it to study whales around the world. There’s a link to their website at ours: L-O-E dot O-R-G. And these are humpback whales, recorded by Roger Payne.

[WHALE SONG]

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth