Audubon’s Birds of America

Air Date: Week of July 27, 2012

|

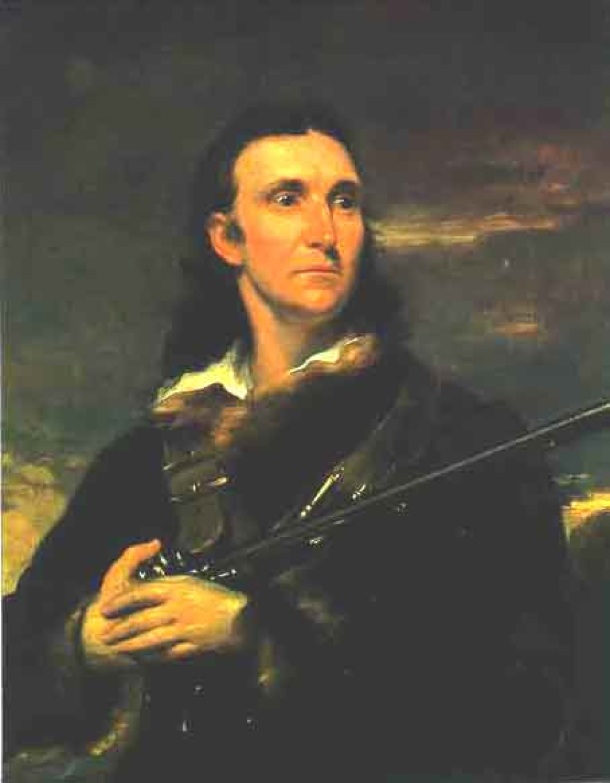

Audubon is a well-known name but, perhaps, the work of John James Audubon is not well-known. But his life-sized paintings of American birds have had a profound effect on the study of natural history. In the 1800’s, the collection of Audubon’s large portraits were made into a book called Audubon’s Birds of America. One of the complete original sets is housed at Amherst College in Massachusetts. Producer Laurie Sanders went to have a look.

Transcript

GELLERMAN: You’re listening to a recycled editition of Living on Earth. I’m Bruce Gellerman. John James Audubon’s book – “Birds of America” -- had a transforming effect on the study of natural history in the United States. The life-size images of the birds are colorful, artistic, and beautifully detailed. One hundred seventy five copies were originally printed but today just 120 of them have survived intact. Naturalist Laurie Sanders found one of the big bird books in Massachusetts at Amherst College.

[KEYS JINGLING]

SANDERS: Every Monday morning, in the lobby of the Special Collections department in Amherst College’s main library, Marion Walker undoes one lock, then another. She removes the back plate of glass from the display case that she and others in Archives call “the bird cage.” With a gentle pull, she slides out a large tray.

WALKER: This is one of the volumes of “Birds of America” by Audubon. It was given by the Pratt family, and we keep one volume out for a certain amount of time, and once a week we turn a page.

SANDERS: The book measures nearly two feet by three feet, and is one of the largest books every printed. Walker leans way over, gently, but firmly grips the page in two places, and slowly flips it over.

Red-winged blackbird, illustrated by John James Audubon. (Photo: Image courtesy of the National Audubon Society)

WALKER: And the paper’s rather-- not absolutely fragile, but we do want to be careful with it.

[SOUND OF PAGE FLIPPING]

WALKER: And there we have the prairie starling.

SANDERS: Today we know this specimen by a different common name—red-winged blackbird. On this plate, Audubon has painted the male and female perched on a shrub, the male with his wings arched to show off his red shoulder patches, the female watching him. The image is one of 435 different birds that Audubon painted for “Birds of America.” Each bird is shown in life size, so relative to the size of the paper, these red-winged blackbirds look small.

WALKER: We do have people who come here every week to see which bird is on display that week. So we have our regulars.

SANDERS: But anyone can come here and ask to see all of the Audubon books.

[KEYS OPENING VAULT]

SANDERS: The other volumes are stored in a locked vault. They’re so heavy and awkward, that archivist Peter Nelson says it takes 2 people to move them onto a cart and roll them to the reference room to look at.

NELSON: Most of the Audubon “Birds of America” are just the plates, and no letterpress printing. But our copy is the only known copy to have the list of subscribers’ names after the title page, and here we see the subscribers' names, about 130 or so of them-- at the very top, his most gracious majesty George the Fourth, King of England.

SANDERS: Audubon came to the United States from France in the early 1800s as a young man, sent by his father to avoid being drafted into the Napoleonic Wars. He was a self-taught artist and naturalist. Once here, his first job was to oversee a lead mine on some family property near Philadelphia.

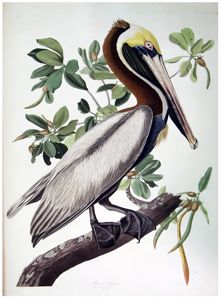

The Brown Pelican by John James Audubon. (Photo: Archives & Special Collections, Amherst College)

But Audubon wasn’t very interested in doing that, and he wasn’t very good at it either. In fact, all of his attempts at later businesses failed too. The main reason is because he was much more interested in being outdoors, exploring, observing and painting wildlife-- especially birds. In 1819 he decided to devote himself entirely to painting and describing all the birds of America.

NELSON: Are you ready for this?

SANDERS: I’m ready.

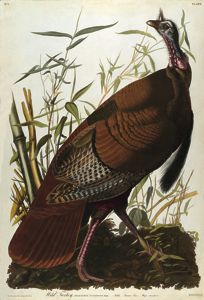

NELSON: Okay. This is the biggie. (TURNS PAGE). Plate 1. One of the most popular Audubon Plates is the Wild Turkey in life size. It fills the entire leaf, pretty much within about a half of an inch or a quarter of an inch to the edge. Audubon painted his birds as naturalistically as possible. This was a very big departure from previous naturalists’ illustrations of birds and animals.

BURK: The worst thing that could happen to a bird was to see Audubon comes towards it, with a shotgun, basically.

SANDERS: John Burk is an Audubon scholar and professor of botany at Smith College.

BURK: He would obviously kill them or buy them dead, very few birds were drawn alive. He worked at this and obviously he devised a way that he could prop the bird up in a life-like position. Essentially he would wire them up in poses and then paint them. And he had a grid so that he could transfer the body onto the paper life-size.

SANDERS: Although the poses Audubon used were sometimes criticized as overly theatrical—or even inaccurate—Burk says Audubon’s “Birds of America” was hugely important.

BURK: First the illustrations made every bird widely available. Secondly there was a text, and it is not as widely read as it should be. It has sort of a rambling tone to it, and people have objected to various aspects of it. But he described every bird that he knew, and gave a great deal of information that certainly is good today.

A Wild Turkey by John James Audubon. (Photo: The National Audubon Society)

SANDERS: In the process of preparing “Birds of America”, Audubon discovered new species of birds. He painted several that are now extinct— Carolina parakeet, passenger pigeon, the Great Auk, Heath Hen.

He was an avid hunter, but he also recognized that the certain species were declining because of over-hunting and habitat changes. Burk says, as a person, Audubon was driven, adventurous, lively and outspoken. He was a storyteller, who sometimes didn’t let the truth get in the way of telling a good story.

BURK: You can look at the “Birds of America” with pleasure, again and again. I mean just leafing through I’m surprised how appealing they are and the drama that’s inherent in many of the pictures.

SANDERS: Unlike modern field guides where the birds are grouped together according to their similarities, Audubon organized Birds of America with a repeating pattern: a big bird, then a medium-sized bird, and then three smaller ones. Given its layout, Marion Walker never knows week to week which species to expect. She says she could look it up in the index, but the surprise is part of the delight of her Monday morning ritual. Still, she doesn’t resist when I ask her to look ahead.

WALKER: [gasps] Oooh! Oh my goodness. It’s the pelican. It’s the brown pelican.

SANDERS: For Living on Earth, I’m Laurie Sanders.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth