July 27, 2012

Air Date: July 27, 2012

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Mozambique Coal Rush

/ Rowan Moore GeretyView the page for this story

Coal is abundant in Mozambique and mining companies from around the world will soon begin exporting coal from the region to China and India. Rowan Moore Gerety reports that coal exports will bring billions of dollars to Mozambique but that gain comes at a price. (08:25)

Urban Farming in Africa

View the page for this story

Persistent drought and desertification are driving 15 million Africans a year out of rural areas and into cities. OnEarth magazine writer Jocelyn Zuckerman tells host Bruce Gellerman that many people in cities are taking up urban agriculture as a way to feed their families. (06:30)

It’s a bird...It’s a plane...It’s a conservation drone!

View the page for this story

Drones are unmanned aircraft often associated with the military. But now they’re being used in the war against deforestation, animal poaching and habitat destruction. Living on Earth’s Bruce Gellerman, talks to the drones’ creator, Lian Pin Koh from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, Switzerland. (06:45)

Music to Help the Forests of Madagascar

View the page for this story

On the African island of Madagascar, the vast majority of plants and animals are endemic, found no place else on Earth. But deforestation is diminishing these riches at a rapid pace. Musician Razia Said talks to host Bruce Gellerman about the music she wrote to raise awareness about the problem in her native island. (08:20)

Sun Oven

View the page for this story

In the dog days of summer, many people try to avoid turning on their kitchen stove. And if you’re like commentator Pat Priest of steamy Athens, Georgia, you prefer cooking with the energy of the sun. (02:15)

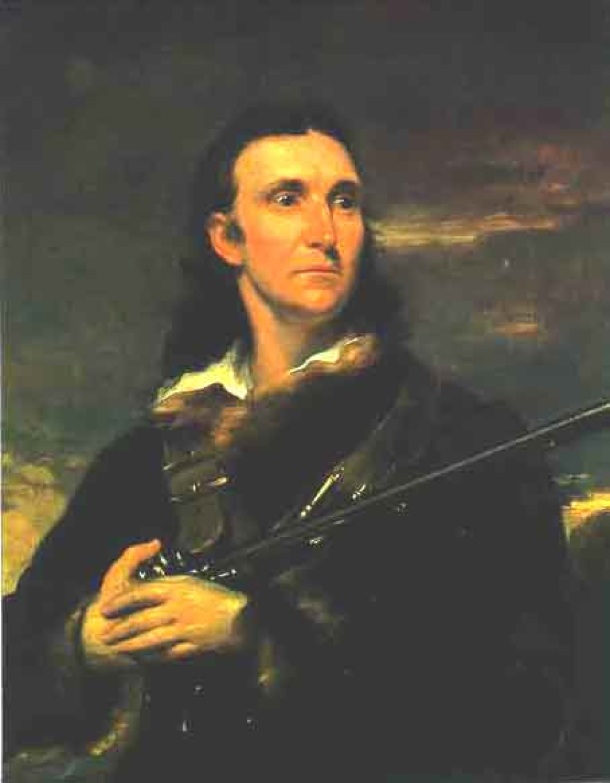

Audubon’s Birds of America

/ Laurie SandersView the page for this story

Audubon is a well-known name but, perhaps, the work of John James Audubon is not well-known. But his life-sized paintings of American birds have had a profound effect on the study of natural history. In the 1800’s, the collection of Audubon’s large portraits were made into a book called Audubon’s Birds of America. One of the complete original sets is housed at Amherst College in Massachusetts. Producer Laurie Sanders went to have a look. (06:10)

The Rap Guide to Evolution

View the page for this story

What do hip hop and Darwin have in common? According to rapper, Baba Brinkman, a lot. He’s the man behind The Rap Guide To Evolution, a musical project that finds natural selection in everything from the iPod shuffle, flashy jewelry to the act of rapping itself. Brinkman explains to host Bruce Gellerman why he, as a white Canadian, can proudly chant, “I’m A African.” (09:00)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Bruce Gellerman,

GUESTS: Jocelyn Zuckerman, Lian Pin Koh, Razia Said, Baba Brinkman.

REPORTERS: Rowan Moore Gerety, Pat Priest, Laurie Sanders.

[THEME]

GELLERMAN: From Public Radio International, it’s Living on Earth. I’m Bruce Gellerman. Mozambique has lots of coal, a lot of coal.

THERON: Well they say it’s the world’s largest undeveloped goal basin, and it’s got huge resources of coking and metallurgical coal. I think there’s a huge demand for coal now, with China and India…everybody that makes steel will be interested.

The coal rush is on in Mozambique, but there’s a price to be paid. And we leaf through a jumbo book: it’s a double elephant folio, but it’s strictly for the birds.

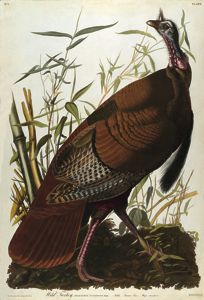

NELSON: One of the most popular Audubon plates is the wild turkey. In life size it fills the entire leaf pretty much within about a half an inch or a quarter of an inch to the edge.

Big birds in a big book, and a lot more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around!

PRI ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the National Science Foundation and Stonyfield Farm.

Mozambique Coal Rush

There’s little access to running water in many communities in the Moatize region of Mozambique. Here, people wash in the Zambezi River near Benga village. (Photo: Rowan Moore Gerety)

GELLERMAN: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Somerville, Massachusetts, this is a recycled edition of Living on Earth. I'm Bruce Gellerman. The red-hot economies of China and India have been cooling off in recent months, but their demand for coal is still voracious. The nations burn coal to provide two thirds of their energy.

And while both China and India are coal rich, they’re still looking overseas for new sources. The east African country of Mozambique is a prime place for a multinational mining company seeking to satisfy their demand, but as Rowan Moore Gerety reports, Mozambique’s coal rush may extract a high price.

[SOUNDS OF CUTTING WOOD, continues in the background]

MOORE GERETY: On the banks of the Zambezi River, Manuel Maenda cuts firewood near his home in Benga village. It’s hot – well over 100 degrees – and Maenda wears a worn nylon cowboy hat to escape the sun.

MAENDA (through translator): I’m cutting this wood to help me get by.

MOORE GERETY: Maenda drags the wood to his bicycle, propped against a tree in a speck of shade. He’ll bring the wood home to cook, or use it to produce charcoal which he sells on the side of the road to Tete, the provincial capital. Maenda points in the distance to large yellow dump trucks clearing rock.

MAENDA (through translator): You see? People lived right there. All the way up to Nganja, over there. Some left at the end of last year. Others went this year.

Rio Tinto relocated some villages to the arid and isolated town of Cateme. There’s no water or hopes for agriculture there. (Photo: Rowan Moore Gerety)

MOORE GERETY: The land now belongs to Rio Tinto, a British-Australian mining company that’s one of the world's largest. Rio Tinto will soon begin exporting coal from Mozambique, primarily to buyers in China and India. Tete is one of the driest regions in the country, and one of its least populated. But the land in the Zambezi river valley is prime real estate, largely because of access to water—and coal.

THERON: Well, they say it's the world's largest undeveloped coal basin, and it's got huge resources of coking and metallurgical coal.

MOORE GERETY: That’s Gerritt Theron, a geologist with the Ncondezi Coal Company. Ncondezi is still in the prospecting phase, but mine construction in the region has already displaced some 2,000 families. Before the resettlements of other villages nearby, Rio Tinto representatives came to Benga to speak with the locals. They promised help, like building a water source right in the village. Manuel Maenda says his community appreciated the gesture.

Manuel Maenda cuts wood for cooking or to make charcoal to sell. (Photo: Rowan Moore Gerety)

MAENDA (through translator): We were having problems with crocodiles attacking people and so forth, and so, they built it, and nobody goes to the river now or has problems with crocodiles.

MOORE GERETY: Now, women wash their clothes in a shaded pavilion in the middle of the village, thanks to the same pipe that brings water to the mine. All around Benga, more dramatic changes are taking place: construction is everywhere.

[SOUND OF CONSTRUCTION]

MOORE GERETY: Multiple hotels are going up. 4x4s are cruising through the bush. I asked Theron who’s driving the boom.

THERON: I think there's just a huge demand for coal now—with China, and India. Everybody that makes steel will be interested in it.

MOORE GERETY: Today, coal accounts for 20% of greenhouse gas emissions and more than a quarter of the world’s energy use. Still, the planet as a whole will burn 50% more coal in 2030 than it does this year. Already, the price of coking coal has increased six-fold in a decade. Prices for thermal coal are also at record-highs.

But the flip side of increased demand is reduced supply. Many experts believe that 'peak coal' — when the world’s maximum coal production rate is reached — will come as early as 2030, or 2025. In China's case, it could be 2015, or even sooner, while China currently mines more coal than the next three largest producers combined. Theron says that this economic pressure has changed the bottom line for mining companies.

THERON: And with the high prices that the guys are willing to pay now, you can exploit these resources which were uneconomical in the past, for instance Tete, which didn't have any railways to the ports or infrastructure.

These Ncondezi Coal Company workers are preparing boreholes for drilling. Their backhoe is down so they’re digging with shovels. (Photo: Rowan Moore Gerety)

MOORE GERETY: The Brazilian mining giant Vale has already begun exports by rehabilitating a colonial railway to the coast. More will have to follow, and ports too - the existing line can only transport a fraction of the coal Vale hopes to produce.

Meanwhile, 35 more companies are looking for coal throughout the province. Ncondezi, for one, has drilled more than 10 miles of boreholes. Today, they've decided to drill one more. With the backhoe out of commission, local workers are preparing the site by hand.

[SOUNDS OF SHOVELING AND FRIENDLY CHAT]

MOORE GERETY: These jobs are one reason that the District Administrator, Manuel Guimaraes, has high hopes for his district, Moatize.

GUIMARAES (through translator): Already, Moatize is advancing. And it's advancing in big steps.

MOORE GERETY: Locally, Guimaraes says that the coal projects have created 1500 jobs for Moatize residents, and brought medical clinics and schools in addition to Benga’s water source. Still, more than half the land in Tete Province has been licensed for prospecting.

Even if only a small number of projects become working mines, the implications for land use and resettlement are extensive. Rio Tinto is lobbying to dredge the Zambezi river and use it to transport coal. Guimaraes and many people here treat the mining projects with an air of resignation.

GUIMARAES (through translator): We all need to understand that mining in Moatize is irreversible. We have to learn to deal with the process because we have no way to stop it. The world today needs the resources that Moatize has.

MOORE GERETY: Local officials may have little choice but to take Guimaraes' view. In 2012, coal from Moatize will boost Mozambique's exports by 13%. With more than half the state budget dependent on foreign aid, mining has become a top priority. Lucia Francisco has worked on community development projects in Tete for more than a decade. She worries that locals have lost out in the government’s eagerness for investors.

These workers are laying railroad tracks to transport coal for Rio Tinto, a British-Australian mining company. (Photo: Rowan Moore Gerety)

FRANCISCO: There is so little community consultation, because all the licenses, and all the projects are being designed in Maputo. The Governor has no say. What he does is to go to the community and say, 'Please, this is not my will, but this part of land has been already allocated to someone. We have to leave'.

MOORE GERETY: All the same, says Francisco, the local people were understanding when they heard about resettlement. Some were even excited. From villages near the river, they were moved to Cateme, 20 miles away. The mining companies Vale and Rio Tinto built them concrete houses, known here as "casas melhoradas," or improved homes. But the houses were poorly built, and there are cracks throughout the walls. The area is isolated and arid.

FRANCISCO: And they are really suffering because there are no rivers or streams that they can get water. No shops.

MOORE GERETY: Cateme is at the end of a bumpy dirt track on a dusty plateau. In the center of the settlement, vendors chat and sift corn at a small market.

[SOUNDS OF SIFTING CORN IN A BASKET]

MOORE GERETY: Farming was an important source of income for the communities that were resettled in Cateme, yet none of this corn was grown here. Even the district administrator, Manuel Guimaraes, recognizes that the lack of water has made agriculture hard.

GUIMARAES (through translator): Right now, frankly, there are problems with pockets of hunger in the population there.

MOORE GERETY: There may soon be other reasons to worry. Studies in the US have linked open cast coal mining to higher rates of cancer, pulmonary diseases and birth defects from air and water pollution. In Moatize, many people and livestock drink straight from the rivers. According to Lucia Francisco, environmental effects of the mines have not gotten sufficient review.

FRANCISCO: And nobody speaks about the pollution. Everybody says the mining is good, because it's bringing money to the nation, but they don't even ask whether this open mining is going to damage their life.

MOORE GERETY: Rio Tinto recently published a report that estimates coal exports will earn Mozambique $15 billion over the next 25 years, but the government has not yet disclosed how mining revenue will be spent. The arrival of ‘peak coal’ globally is expected to push coal prices even higher. Mining companies here will surely gain as a result. The locals are hoping they will too. For Living On Earth, I’m Rowan Moore Gerety in Tete, Mozambique.

Coal companies, including Rio Tinto and Ncondezi Coal, are prospecting for coal in Benga. Rio Tinto installed a pipe to bring water to the village. (Photo: Rowan Moore Gerety)

GELLERMAN: And we have an update to our story. Mining giant Rio Tinto just exported its first shipment of coal from Mozambique. The coal is headed to a steel mill in India.

[MUSIC: African Virtuosos “Madame Nana” from The Classic Guinean Guitar Group (Sterns Africa 2007)]

Urban Farming in Africa

Kibera is the largest slum in Nairobi, Kenya and ground zero for urban farming. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

GELLERMAN: Nairobi, Kenya, is a bustling business city, but it’s also on the bleeding edge of climate change. Rainfall disruptions and drought have led to a mass migration from rural areas of the country to the city. And today 60 percent of the population of Nairobi live in slums. “Hell on Earth” is how Jocelyn Zuckerman describes these impoverished places. But writing in OnEarth magazine, she says that the slums of Nairobi are also on the leading edge of urban agriculture and what is called “vertical farming.” For her article, "The Constant Gardeners," Jocelyn Zuckerman traveled to the city’s vast shantytown called Kibera.

ZUCKERMAN: Most of the buildings are made of just sort of scraps of cardboard or mud - corrugated tin roofs on top of each other, really, with just little dirt alleys running between them, and laundry hanging all over open sewage that you have to step over and around. But there’s also lots of little stores and barbershops and butchers and bakeries, so there’s a lot of industry happening there - a lot more than people realize, I think.

GELLERMAN: And a lot of people. And a lot of people without food.

ZUCKERMAN: Yeah, people are really hungry there. There was a study that was recently done, and I think it was something like 20 percent said that they had gone a day and a night without food in the last couple of months. Poor people around the world - especially in cities where they don’t have access to land to grow their own food - generally spend from 75 to 80 percent of their incomes just on food.

GELLERMAN: So, this is an area that’s already feeling the effects of climate change, it’s sub-Saharan, there’s… the desert is moving further south, and it’s pushing people into cities, mass exodus.

ZUCKERMAN: Right, the desert is moving further south, and also the cycles of the weather are shifting. So the dry periods are longer, and the rains are coming at times when they’re not expecting them. They’re also tending to be more extreme - a lot of rain - and when a lot of rain falls on the land that’s been dry for so long, it can’t absorb it. So they’re finding it much more difficult to farm. In that part of the world, something like 15 million people are moving to the cities every year.

GELLERMAN: And you write that by 2050, two thirds of the world’s population will be living in cities.

ZUCKERMAN: Right, that’s according to the UN.

GELLERMAN: And they’re turning what little land they have into farms.

ZUCKERMAN: They are. They’re doing some of it in what they call vertical gardens, which are just recycled grain sacks. It’s about three feet tall and a diameter of probably a foot and a half. And they fill them up with some rocks to give it some structure, and then dirt, and they poke some holes in the side and plant… it’s kale, they call it sukuma wiki there, which is Swahili for “to push through the week” because it grows pretty quickly and, you can buy it cheap. So it’s pretty much the staple that Kenyans rely on. And so they’re growing that and scallions and cabbage in these vertical gardens. At first I saw one or two in front of various shacks, and then at one point, I turned a corner and there were something like 35 of them. And as I walked around the settlement, I just saw more and more of them.

GELLERMAN: Where do they get the water for their sacks?

ZUCKERMAN: Well, a lot of them are reusing wastewater. There are some public taps, but I think something like 100 people share a single tap, and that’s water for, you know, cooking, bathing. So, in terms of gardening, they’re often reusing wastewater - water that’s been used for maybe washing dishes or washing laundry. It’s that or nothing. These people are living in real desperation, and they’re finding ways around it.

GELLERMAN: In your article, you mentioned prominently a farmer, his name is Francis Wachira, have I pronounced that correctly?

ZUCKERMAN: Yes, Francis Wachira.

GELLERMAN: He’s quite a guy.

ZUCKERMAN: He’s a fantastic guy, he really is. He struggled for a long time living in the city. He wanted to farm. He started trying to do it and people made fun of him because there’s a lot of stigma attached to what people do in cities and what people are meant to do in the countryside. And he stuck with it. And now he’s got a pretty good-sized farm. He’s growing all sorts of vegetables and fruits.

GELLERMAN: How big is his plot?

ZUCKERMAN: It’s about a quarter of an acre. It’s amazing. In addition to all the fruits and vegetables, he’s got 500 rabbits there. He’s got wooden hutches - cages that he built himself - three stories high, each of which can have 2-5 rabbits, I would say, in there. And he feeds them with kitchen scraps and grass from his farm, and then he composts everything to use the nutrients to put back into his farm.

GELLERMAN: Well, we spoke with Francis Wachira - we called him up. I want you to hear what he said to us.

Farmers use any open available open space to grow their crops. (Photo: BBC World Service)

WACHIRA: Actually when I started this urban farming it was like a miracle - I’m feeding my family, a family of five. Everybody here is growing some vegetables. So, actually, the future of the world depends on urban farming. If we don’t encourage people to grow food in the urban areas, we are going to have a shortage of food.

GELLERMAN: Well, Francis Wachira, who you just heard from, actually traveled to the United States and he had things to teach Americans about farming.

ZUCKERMAN: Absolutely. He was a really inspirational figure. He was in the states for six weeks in Denver talking with farmers. And at one point, he gave this speech and he was talking about his rabbits - his 500 rabbits that he's raising in downtown Nairobi - and at the end of the speech, the whole crowd was on their feet shouting ‘Rabbit King, Rabbit King.’ And he understood that he really had something to teach these people.

GELLERMAN: So Jocelyn, is urban agriculture the face of farming in the future?

ZUCKERMAN: I think it absolutely is. I mean, I don’t think we’re going to have a choice, especially with the populations moving to the cities the way they are, and also our land being degraded. The soils in Africa in particular are so tired, they’re just not growing crops well. So people are needing to figure out other ways to do it, and these low tech methods that they’re using in Africa are really impressive and they’re sustainable.

GELLERMAN: Jocelyn, thanks so much for joining us. I really appreciate it.

ZUCKERMAN: Thanks for having me.

GELLERMAN: Jocelyn Zuckerman’s article “The Constant Gardeners” appeared in OnEarth Magazine. It’s published by the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Related link:

Read the OnEarth Article

[MUSIC: Various Artists/Orchestra Regional de Kayes: Sanjina from World Psychedelic Classics Vol 3 (Luaka Bop Records 2005)]

GELLERMAN: Just ahead, Nuevo fusion cuisine. Cooking with solar. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Various Artists/ Money Mark & Los Lobos: “Pepe & Irene” from Red Hot + Latin Redux (Nacional Records 2006)]

It’s a bird...It’s a plane...It’s a conservation drone!

Lian Pin Koh and Serge Wich with their conservation drone. (Photo: Lian Pin Koh)

GELLERMAN: It’s a recycled edition of Living on Earth, I’m Bruce Gellerman.

[WINDING SOUND]

GELLERMAN: Environmentalists have a new weapon in their war on deforestation, poaching of endangered species…

[BEEPING SOUND]

GELLERMAN:…and the destruction of animal habitats.

[DRONE ENGINE SOUNDS, FLYING SOUND]

GELLERMAN: Drones. Fleets of small, self-flying airplanes could soon become part of the eco-arsenal.

[SOUND OF DRONE TAKING OFF]

GELLERMAN: A tropical forest clearing in Sumatra serves as a runway—as Lian Pin Koh test-flies his conservation drone. Quickly airborne, the drone’s cameras capture a bird’s eye view of the dense forest below.

[DRONE STARTING TO LAND]

GELLERMAN: But Lian Pin Koh found that some of the test flight landings were rougher than expected.

[ROUGH LANDING SOUND]

Lian Pin Koh plotting the drone’s course. (Photo: Lian Pin Koh)

GELLERMAN: When he’s not in Sumatra testing his eco-surveillance plane, Professor Lian Pin Koh teaches ecology and conservation at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich. He’s co-developer of the conservation drone One-Point-O, and says the idea of using small, self-flying airplanes is really taking off.

KOH: So it's basically just a hobby, remote-control model plane that you can buy from any hobby shop. It has a wing-span of about 1.4 meters, so it’s pretty small and it's very compact. We can basically put it in a backpack and carry it around in the forest.

GELLERMAN: How far does it go and how high does it go?

KOH: It can fly for about 20 to 25 minutes, which gives it a range of about ten to 15 kilometers and it can be programmed to fly up to maybe about 300 meters above ground.

GELLERMAN: About a thousand feet.

KOH: Right. But the cool thing about this system is we’ve incorporated an autopilot system into this model airplane, which essentially makes it into a drone.

GELLERMAN: So, this plane flies itself?

KOH: Correct, it flies itself, autonomously!

GELLERMAN: (Laughs.) So, it’s the autonomous nature of the plane - that you have this software that allows it to fly itself - that’s the innovation that you bring to this.

An oil palm plantation photographed by the drone. (Photo: Lian Pin Koh)

KOH: Well, yes. But I should say that the autopilot hardware and software have been developed by a group of online developers and hobbyists, so it is open-source software. So, what we did was to take this system and apply it to our research area, which is tropical conservation.

By strapping a camera on the belly of the plane you can easily see the plumes of smoke on the horizon, and those could be illegal burning activities that many of the local rangers and forest mangers want to be able to control and to keep track of. The other would be taking aerial photos to produce real-time land cover maps.

GELLERMAN: What about tracking wild animals?

KOH: Yeah, that’s the third main purpose of these drones: to be able to count the number of cheetahs or antelopes or elephants, which would be already a huge cost savings, because what’s currently being done is that ecologists go on manned aircrafts to try to do those kinds of surveys and that can be very, very expensive.

So I should also add, that when we began using drones for conservation, we actually decided to first buy a commercial system that costs tens of thousands of dollars and we found that it doesn’t really do all the things that we wanted it to do, and besides, it cost a huge amount of money, which many local conservation workers in the tropics would not be able to afford.

GELLERMAN: So how much did your system cost?

KOH: So, our system costs less than two thousand dollars.

GELLERMAN: Wow!

The drone’s photo of an orangutan high up in a tree. (Photo: Lian Pin Koh)

KOH: Including the cameras and the electronics and the plane and the software, but the software is open-source, of course.

GELLERMAN: So when you’re about to fly this drone, what do you do, you program it? How do you make it go where you want it to go?

KOH: That’s very simple. We just basically have to click on waypoints on a Google map - we just upload it to the drone and flick a switch on the radio system and it takes off on its own and goes about its mission. And after it’s done with the mission, it flies back to us.

GELLERMAN: Professor Koh, why not use satellites for imaging the rainforest?

KOH: Yeah, we have been using satellites as well, but a couple of problems: one is the cost, and the second reason is because in many parts of the humid tropics, there is persistent cloud cover, so it’s very difficult to get real time images from a particular location using satellite-based remote sensing.

GELLERMAN: You know, Professor Koh, have you thought of this, that you’re flying this drone over a forest, and you hone in on a deforester, someone who is cutting down trees, and they start shooting at the drone, and maybe shooting at you.

The drone took this aerial photo of a roaming elephant. (Photo: Lian Pin Koh)

KOH: Actually, being shot at was one of the motivations for developing the drone too! Being shot at is a big risk of having manned aircraft flying over forests looking for illegal loggers, or poachers, so if the drone gets shot at, it’s the drone that goes down, it’s only a two thousand dollar technology. It’s practically disposable compared to a manned aircraft or an ultra-lite.

GELLERMAN: Since you’ve had successful test flights, have environmental groups coming to you saying, ‘hey, we could use that’?

KOH: Yeah, we’ve got lots of people contacting us, we’ve got colleagues from other research institutes asking us to go to Borneo to fly over the rainforest, asking us to go to Africa and we’ve even got someone asking us to bring our drones to the Antarctica to film penguins!

GELLERMAN: Professor Koh, were you the kind of kid - I know I was - who flew model airplanes and all that?

KOH: No, no. I wanted to fly, but we just couldn't afford to buy one of those things in my family, so I’m sort of living my childhood dream now. You know, one of my dreams is to be able to develop something that is of real practical use to conservation in the tropics, apart from all of the academic work that I’m engaged in, to reach out to the people on the ground who are actually doing conservation.

Photos like this taken by the drone can show logging in a forest. (Photo: Lian Pin Koh)

GELLERMAN: Is it fun to fly?

KOH: Oh, it’s very fun! That’s the other reason why we developed the drone! (Laughs)

GELLERMAN: (Laughs) Well, congratulations Professor Koh, you’ve earned your wings!

KOH: (Laughs) Oh, thank you very much.

GELLERMAN: Lian Pin Koh is a professor of ecology and conservation at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich.

Related link:

Learn more about the conservation drones, and watch videos

[MUSIC: Youssou N’Dour “Medina” from Set (Virgin Records – 1990)]

Music to Help the Forests of Madagascar

Ten percent of the profits from Razia Said's CD go to Reforestation efforts near Masoala National Park. (Photo: Razia Said)

GELLERMAN: Three hundred miles off the southeast coast of Africa is Madagascar. It’s the fourth largest island in the world; smaller than Texas but larger than California. Seventy percent of the plants on Madagascar and 80 percent of the animals are found no place else on Earth. It's biologically rich because it’s remote and has a wide diversity of forest habitats. But the island nation is economically impoverished and the forest resources are rapidly being removed. In just 20 years, Malagasy forests, equal to the size of Connecticut, have been cut down. Musician Razia Said is from Madagascar. She’s recorded a CD about the destruction of forests in her homeland. It’s called: Zebu Nation.

SAID: The zebu is a cattle that is very common in Madagascar and means a lot of things for the Malagasy people. The zebu represents the connection between the world of the living and the world of the dead. We eat the zebu, as well. It’s the daily meat of Madagascar, so it has a lot of different layers of meanings.

[MUSIC: Said: Razia “Slash and Burn" from Zebu Nation (Cumbancha Records 2011).]

GELLERMAN: Well, your album is basically an impassioned plea for preserving the forest of Madagascar.

Malagasy musician Razia Said (Photo: Razia Said)

SAID: I realized that there was not much that was done about that. I decided to do something about it, so I decided to write about this environmental, you know, disaster that we’re going through in Madagascar.

[MUSIC: Said: Razia “Slash and Burn” from Zebu Nation (Cumbancha Records 2011).]

SAID: One thing that is going on is slash and burn agriculture. You know, people are burning the forests in order to fertilize the soil, but after three crops, the soil is totally impoverished from its nutrients. At the end it becomes just some soil that is eroded. It’s a huge, huge problem in Madagascar because this is something that people have been doing for generations.

[MUSIC: Said: Razia “Slash and Burn” from Zebu Nation (Cumbancha Records 2011).]

SAID: There’s also the big problem of poverty. We are one of the poorest countries in the world, so it’s very difficult to make people understand something when they have to figure a way to live on a daily basis and how they’re going to feed their children the next day.

[MUSIC: Said: Razia “Slash and Burn” from Zebu Nation (Cumbancha Records 2011).]

GELLERMAN: Some of your trees are worth huge amounts of money – you’ve got ebony and rosewood. These are very exotic and very expensive trees.

Lowland Rainforest in Masoala National Park, Madagascar. (Photo: Frank Vassen)

SAID: Yes, very expensive once it comes out of Madagascar, but actually people are getting it for pretty cheap from Madagascar. So this is - this is the other layer of the big problem in Madagascar which is illegal logging. They’ve cut everything that was outside of national parks and they’re going into national parks.

You know, can you imagine if people go to Yellowstone, and get into the park and just start cutting the trees? People would be totally like outraged here in the States, I’m sure. In Madagascar, I’m trying to make people realize that these trees are worth much more than whatever they’re getting. But then again, you’re facing the same problem, which is they think about what’s happening today and tomorrow but they’re not thinking about much more than that.

GELLERMAN: Is that the reason that you wrote and sang the song on your album ‘Mifohasa’? Did I pronounce and say that correctly?

SAID: Yeah, Mifohasa. Mifohasa, which means Wake up!

[MUSIC: Said: Razia “Mifohasa” from Zebu Nation (Cumbancha Records 2011).]

SAID: This is what this song is about: let’s stop cutting this wood because these forests could bring so much more to Madagascar because Madagascar is known for its biodiversity and for its beautiful endemic species, and if we cut these trees, we’ll have no more animals living in them. We’ll have no trees, we’ll just become a desert.

GELLERMAN: All of your songs have been translated to English in the liner notes and it says ‘Don’t let anyone pretend to have the right to use them to fulfill their own greed.’

Madagascar is home to 33 different species of Lemur. They are all unique and live nowhere else on earth. (Photo: Frank Vassen)

SAID: Yes, absolutely.

GELLERMAN: Who are you talking about?

SAID: Specifically now, this case of Gibson, you know about the illegal wood. But it’s not just Gibson, you know…

GELLERMAN: Gibson Guitar?

SAID: Yes, Gibson Guitar. We have a lot of wood that had been exported to China. The people in Madagascar are not seeing really much money from this wood. They are getting paid two dollars fifty a day to go get some wood in the middle of national parks that they’re dragging through miles and miles to get them to some port where they leave Madagascar illegally. It’s horrible.

GELLERMAN: We should say, though, that Gibson Guitar Company has said they deny the allegations, that they have anything to do with illegal logging.

[VIDEO CLIP OF CONCERT]

GELLERMAN: We have a video of a concert of some Malagasy musicians who held a concert there in support of the rainforest.

SAID: Yes, this is what I did in October, I organized this concert. It was next to the national park of Masoala. People have been going into the park and cutting some trees. The concert attracted about ten thousand people.

[SOUNDS OF CONCERT IN MADAGASCAR]

SAID: It felt like it was not right to cut that forest. They showed us some wells and they started saying, ‘can you believe there was no more water in these wells; there were cobwebs.’ We tried to explain to them, you know, when you don't have any more forest, this is what happens, you know, it just dries up.

Razia Said in concert (Photo: Razia Said)

This is on the northeast corner, where I come from, of Madagascar. When I grew up I used to walk along that park because my grandfather was doing some agriculture, some coffee, some cloves, in that area. So it’s something that is really, really close to me. And, when I went there… now, I’m getting emotional talking about all of this - when I went there a year ago and I started speaking to people, introducing myself and they remembered my grandfather because, you know, he’s gone since. And they say ‘Oh, my God, you’re the granddaughter of this person,’ and they say, ‘Please do something to help us - do something to help us.’

GELLERMAN: I want to ask you about this song ‘Ny Alantsika.’ Did I say that right?

SAID: Ny Alantsika, Ny Alantsika.

GELLERMAN: What does that mean?

SAID: It’s nature’s lament, you know, what’s happening to our nature, and if we’re not careful, we’re not going to have anything left for future generations. Nature is begging for help.

GELLERMAN: Can you sing it there? I know that we’re not set up to do this but I just want to hear you sing.

SAID: (LAUGHS) Well, I don’t have any instrument around here but, okay…

[SINGS NY ALANTSIKA]

[MUSIC: Said: Razia “Ny Alantsika” from Zebu Nation (Cumbancha Records 2011).]

SAID: I think that there is something to be done, and we need to do it fast. You know, Malagasy people cannot do it on their own and I will not say it enough: we really need your help.

GELLERMAN: Boy. Razia, thank you so very much.

SAID: Thank you.

Related links:

- Razia Said’s Home Page

- Click here for a petition against illegal logging in Madagascar

[MUSIC: Said: Razia “Ny Alantsika” from Zebu Nation (Cumbancha Records 2011 http://www.raziasaid.com/main.html).]

GELLERMAN: Razia Said’s CD is Zebu Nation. Some of the profits from sales go to reforesting Madagascar. Our website has more information, it's LOE dot org.

[MUSIC CONTINUES]

Sun Oven

GELLERMAN: As former president Harry Truman once said, “If you can't stand the heat, get out of the kitchen.” Well, with the dog days of summer upon us, that’s just what commentator Pat Priest of Athens, Georgia does.

An aluminum reflective collar surrounds the cooking bowl, amplifies the heat of the sun.(Photo: Pat Priest)

PRIEST: When you say, "It's like an oven out there!"…when one baking hot day follows another, try baking outside using the free radiant heat of the sun. I’m cooking some beets this afternoon in my side yard in my solar cooker as I write this. I occasionally have to adjust the cooker slightly to orient it more squarely towards the sun. But other than that, it’s simple, working like a crock-pot you can leave all day while you’re at work. No plug needed, no danger of fire. The only problem I’ve ever had is that someone ran over mine in the driveway once, causing an explosion of glass and garbanzos.

Most sun ovens are shaped like the Elizabethan collar that you put on your dog so it won’t lick and scratch its wound - the shiny collar funnels the sun inward. The oven I use costs a little over a hundred bucks. It’s a black, enamel bowl that sits inside a rounded glass bottom and top, creating a greenhouse effect. I set the pot inside that reflective collar that cantilevers outward to surround the meal I’m cooking - it’s dazzling, really, gotta wear shades.

With my solar stove, I can cook without using electricity, which I avoid because of the CO2 emissions and the mountain top removal associated with coal-fired power plants. And when I’m cooking outdoors, I don’t have to use more energy still to cool my kitchen on these stiflingly hot days. I love to be outdoors working in my garden and catch a whiff of my dinner cooking. And the neat part about the company that makes my solar cooker is that a portion of its sales helps send these simple devices to developing countries. Fuel is expensive. And cooking with wood or dung is harmful to people’s health. Solar cooking limits the deforestation that happens when poor people cut trees for wood stoves. So there, and here, solar ovens make sense. Sun powered, and very cool.

GELLERMAN: Pat Priest produces a radio program called “True South” in Athens, Georgia. For more information on solar stoves, go to our website – loe.org.

(Photo: Pat Priest)

[MUSIC: Thunderball “Solar” from Scorpio Rising (ESL Music 2001)]

GELLERMAN: Coming up - Darwin evolves, a hip-hop version of the Origin of Species. Keep up the beat at Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and Gilman Ordway, for conservation and environmental change. This is Living on Earth on PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Junior Walker “Cleo’s Mood” from Jr Walker And The All Stars: The Definitive Collection (Motown Records reissue 2008)]

Audubon’s Birds of America

GELLERMAN: You’re listening to a recycled editition of Living on Earth. I’m Bruce Gellerman. John James Audubon’s book – “Birds of America” -- had a transforming effect on the study of natural history in the United States. The life-size images of the birds are colorful, artistic, and beautifully detailed. One hundred seventy five copies were originally printed but today just 120 of them have survived intact. Naturalist Laurie Sanders found one of the big bird books in Massachusetts at Amherst College.

[KEYS JINGLING]

SANDERS: Every Monday morning, in the lobby of the Special Collections department in Amherst College’s main library, Marion Walker undoes one lock, then another. She removes the back plate of glass from the display case that she and others in Archives call “the bird cage.” With a gentle pull, she slides out a large tray.

WALKER: This is one of the volumes of “Birds of America” by Audubon. It was given by the Pratt family, and we keep one volume out for a certain amount of time, and once a week we turn a page.

SANDERS: The book measures nearly two feet by three feet, and is one of the largest books every printed. Walker leans way over, gently, but firmly grips the page in two places, and slowly flips it over.

Red-winged blackbird, illustrated by John James Audubon. (Photo: Image courtesy of the National Audubon Society)

WALKER: And the paper’s rather-- not absolutely fragile, but we do want to be careful with it.

[SOUND OF PAGE FLIPPING]

WALKER: And there we have the prairie starling.

SANDERS: Today we know this specimen by a different common name—red-winged blackbird. On this plate, Audubon has painted the male and female perched on a shrub, the male with his wings arched to show off his red shoulder patches, the female watching him. The image is one of 435 different birds that Audubon painted for “Birds of America.” Each bird is shown in life size, so relative to the size of the paper, these red-winged blackbirds look small.

WALKER: We do have people who come here every week to see which bird is on display that week. So we have our regulars.

SANDERS: But anyone can come here and ask to see all of the Audubon books.

[KEYS OPENING VAULT]

SANDERS: The other volumes are stored in a locked vault. They’re so heavy and awkward, that archivist Peter Nelson says it takes 2 people to move them onto a cart and roll them to the reference room to look at.

NELSON: Most of the Audubon “Birds of America” are just the plates, and no letterpress printing. But our copy is the only known copy to have the list of subscribers’ names after the title page, and here we see the subscribers' names, about 130 or so of them-- at the very top, his most gracious majesty George the Fourth, King of England.

SANDERS: Audubon came to the United States from France in the early 1800s as a young man, sent by his father to avoid being drafted into the Napoleonic Wars. He was a self-taught artist and naturalist. Once here, his first job was to oversee a lead mine on some family property near Philadelphia.

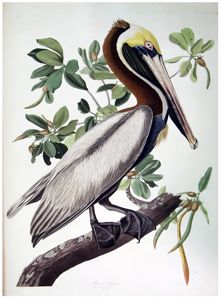

The Brown Pelican by John James Audubon. (Photo: Archives & Special Collections, Amherst College)

But Audubon wasn’t very interested in doing that, and he wasn’t very good at it either. In fact, all of his attempts at later businesses failed too. The main reason is because he was much more interested in being outdoors, exploring, observing and painting wildlife-- especially birds. In 1819 he decided to devote himself entirely to painting and describing all the birds of America.

NELSON: Are you ready for this?

SANDERS: I’m ready.

NELSON: Okay. This is the biggie. (TURNS PAGE). Plate 1. One of the most popular Audubon Plates is the Wild Turkey in life size. It fills the entire leaf, pretty much within about a half of an inch or a quarter of an inch to the edge. Audubon painted his birds as naturalistically as possible. This was a very big departure from previous naturalists’ illustrations of birds and animals.

BURK: The worst thing that could happen to a bird was to see Audubon comes towards it, with a shotgun, basically.

SANDERS: John Burk is an Audubon scholar and professor of botany at Smith College.

BURK: He would obviously kill them or buy them dead, very few birds were drawn alive. He worked at this and obviously he devised a way that he could prop the bird up in a life-like position. Essentially he would wire them up in poses and then paint them. And he had a grid so that he could transfer the body onto the paper life-size.

SANDERS: Although the poses Audubon used were sometimes criticized as overly theatrical—or even inaccurate—Burk says Audubon’s “Birds of America” was hugely important.

BURK: First the illustrations made every bird widely available. Secondly there was a text, and it is not as widely read as it should be. It has sort of a rambling tone to it, and people have objected to various aspects of it. But he described every bird that he knew, and gave a great deal of information that certainly is good today.

A Wild Turkey by John James Audubon. (Photo: The National Audubon Society)

SANDERS: In the process of preparing “Birds of America”, Audubon discovered new species of birds. He painted several that are now extinct— Carolina parakeet, passenger pigeon, the Great Auk, Heath Hen.

He was an avid hunter, but he also recognized that the certain species were declining because of over-hunting and habitat changes. Burk says, as a person, Audubon was driven, adventurous, lively and outspoken. He was a storyteller, who sometimes didn’t let the truth get in the way of telling a good story.

BURK: You can look at the “Birds of America” with pleasure, again and again. I mean just leafing through I’m surprised how appealing they are and the drama that’s inherent in many of the pictures.

SANDERS: Unlike modern field guides where the birds are grouped together according to their similarities, Audubon organized Birds of America with a repeating pattern: a big bird, then a medium-sized bird, and then three smaller ones. Given its layout, Marion Walker never knows week to week which species to expect. She says she could look it up in the index, but the surprise is part of the delight of her Monday morning ritual. Still, she doesn’t resist when I ask her to look ahead.

WALKER: [gasps] Oooh! Oh my goodness. It’s the pelican. It’s the brown pelican.

SANDERS: For Living on Earth, I’m Laurie Sanders.

Related links:

- Amherst College Archives and Special Collections

- Audubon’s Birds of America

[MUSIC: Jimi Hendrix “Everlasting First (Anthology Version) from West Coast Seattle Boy (Sony Music 2010)]

The Rap Guide to Evolution

GELLERMAN: Beats, rhymes, and evolutionary biology are what you’ll hear on the musical project - A Rap Guide to Evolution.

[MUSIC: “Natural Selection”…(SINGING: So long, the weak and the strong. We’ve got it going on. Creationism is dead wrong - the weak and the strong. Who got it going on? Whoever leaves the most spawn. Darwinism has got it going on. Creationism is erroneous. Erroneous…]

GELLERMAN: In the lab with a pen and a pad is Baba Brinkman. He’s a Canadian rapper with a Master’s degree in English and a passion for Darwin. Baba, welcome to Living on Earth.

BRINKMAN: Thanks a lot, Bruce, thanks for having me on!

GELLERMAN: So where did the idea for the Rap Guide to Evolution come from?

BRINKMAN: It came from a scientist. I don’t take credit for it - it was a commission. The thing that I was doing at the time was another project called the Rap Canterbury Tales and it was, you know, Geoffrey Chaucer remixed as hip-hop.

And a scientist saw that show - heard that show - and his name is Mark Pallen - he’s in Birmingham, UK- he studies bacterial genetics, and he said, you know, if you could do the Canterbury Tales, could you do the Origin of the Species next and he had a budget from the British Council to create an event for Darwin’s birthday and the Rap Guide to Evolution was the entertainment.

GELLERMAN: We’re going to listen to a selection from your album, it’s called “Natural Selection,” naturally.

BRINKMAN: Alright.

[MUSIC: Baba Brinkman: "Natural Selection 2.0" from The Rap Guide to Evolution: (June 2011) ]

DAWKINS: Whoever is left to believe that species are immutable will do good service by conscientiously expressing his conviction…For only thus can the load of prejudice by which this subject is overwhelmed be removed. Be removed…

BRINKMAN: That’s Richard Dawkins reading The Origin of Species, reading Darwin’s words. That’s basically, if you believe in evolution, you need to tell people that you believe in evolution because that’s what’s going to make all of the prejudice or the misunderstandings or the tension around it disappear.

[MUSIC: Baba Brinkman: "Natural Selection 2.0" from The Rap Guide to Evolution: (June 2011) ]

RAPPING: So what do you know about natural selection? Go ahead and ask a question and see what the answer gets you. Try being passive aggressive or try smashing heads in and see which tactic brings your plans to fruition. And if you have an explanation in mind, then you’re wasting your time because the best watchmaker is blind. It takes a certain base kind of impatient mind to explain away nature with intelligent design. It’s time to elevate your mind-state and celebrate your kinship with the primates (monkey sounds). The way of the strong, we’ve got it going on, we’ve lived in the dark for so long.

GELLERMAN: Well Baba, I understand that this may be the first scientifically peer-reviewed album in history.

BRINKMAN: That does seem to be the case, yeah! Which, you know, wasn’t really my original intention with it, but it basically came from the scientist Mark Pallen and he said: Look, you know if you’re going to rap about evolution, you need to make sure that you represent evolution accurately and don’t misconstrue what it actually means and how it works. So I’m going to ask you to send me drafts of your rap lyrics so I can check them for accuracy. So I had all of my raps checked before the performance.

GELLERMAN: So, how has it fared on stage, have you found success?

BRINKMAN: Yeah, well, it started onstage at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival in Scotland and it won an award there and a Broadway producer saw it and she optioned the rights to it and we started in June. We had over 10,000 people come see it in New York and now it’s going to be touring to colleges and performing arts centers around the country.

My hope is to take it to places that are slightly less culturally friendly towards evolution. If you can make people laugh at evolution and tap their feet along with it - it just makes it less scary.

GELLERMAN: We’ll have to see how your music evolves…

BRINKMAN: Yeah. The process is called “Performance, Feedback, Revision,” you put it on stage, you try it for people, you get their impressions, you talk to them, you get the feedback and then you fine-tune based on what they say.

[MUSIC: Baba Brinkman: "Performance, Feedback, Revision 2.0" from The Rap Guide to Evolution: (June 2011) ]

RAPPING: Well, sometimes people ask me, well how does your show get written. Like this: performance, feedback, revision. And how do I generally develop my lyricism: performance, feedback, revision. And how do human beings ever learn to do anything? Like this: performance, feedback, revision. And evolution is really just kind of an algorithm that kind of just goes like this: performance, feedback, revision. So, the…

BRINKMAN: I mean, I noticed similarities between things that rappers were saying and things that biologists were saying and ways in which hip-hop was a kind of showcase of the kinds of behaviors that evolution has been applied to: cooperation, aggression, mating dances, costly signaling displays…

GELLERMAN: In evolutionary terms, is there a role for “bling” in the rap world?

BRINKMAN: Absolutely. Yeah, bling features quite largely in the off-Broadway show. The peacock’s tail is the classic example because if you have some kind of a flaw in your genes, or you’re, you know, not strong - then it’s impossible to grow that large of a tail and carry it around and not get killed by a predator. So the tail is a handicap that’s an advertisement of its own cost and I think that’s what bling is as well. If you can afford to carry bling around, then it means you’re winning the game.

It’s your fashion sense, or your Harvard degree that you're showing off that hangs on the wall or the fact that you raised a couple of kids that are whip-smart or winning at something. You know, there are a lot of things that we display to each other to try to advertise something about ourselves. And bling just happens to be the sort of symbolism that hip-hop has settled on but anything could suffice as long as it’s difficult to fake and costly and represents your resources.

GELLERMAN: You know, I don't think I’ll ever listen to rap or look at a peacock again the same way.

BRINKMAN: Well, that really is my goal, as well as teaching people about evolution. I want people to appreciate rap, and you know, not just as some kind of aggressive chest-beating display. A lot of people take it for negativity and materialism and misogyny and all that, but it comes from a specific cultural context and it’s not just about the material bling - it’s about the verbal bling - the skill with words and storytelling, craft. And it’s a sort of virtuoso display of linguistic ability, which is also very difficult to fake. Anybody who doesn’t get it is either missing something - very similar to evolution actually, both rap and evolution are massively hated on, and I’m trying to redeem them.

GELLERMAN: Tell me about the cut “I’m a African.” It’s not “I’m AN African.” You’ve got a master’s degree in English - shouldn’t it be “I’m an African?”

BRINKMAN: Well, that’s me being respectful of the social context of the original track that that remixes. So “I’m a African” is actually a track by Dead Prez which is a rap group originally from Florida. Their version is based on Peter Tosh - that says: As long as you’re a black man, then you’re a African.

It’s sort of a reggae song that Peter Tosh made, sort of basing it on Garvey. And I'm just making the point that actually, that’s true for all black people if you go back 500 years. But it’s true for all living humans if you go back 500 centuries. Between 50 and 70 thousand years ago is when the first modern humans first left Africa and all of the races are descended from those first emigrants. And then, that’s actually not that much time. That makes racial differences superficial.

[MUSIC: Baba Brinkman: " I’m a African 2.0" from The Rap Guide to Evolution: (June 2011) ]

RAPPING: I wasn’t born in Ghana but Africa is my momma, because that’s where my momma got her mitochondria. You can try to fight it if you wanna, but it’s not going to change me because it’s plain to see Africans are my people. It’s not plain to see that your eyes deceive you - I’m talking primeval. The DNA in my veins tells a story that reasonable people find believable but it might even blow your transistors. Africa is the home of our most recent common ancestors which means human beings are our brothers and sisters…

BRINKMAN: I feel like the whole human race can shout it in unison:

[MUSIC: “I’m a African.” (Rapping: I’m a African, I’m a African and I know what’s happenin’… yeah.)]

BRINKMAN: And by the way, the grammatical thing, it’s all about the rhythm, right? I’m a African, I’m a African, but if you say I’m an African, and you say it that way and say it grammatically properly, it becomes I'm a Nafrakin and the word “Naf” just sounds wrong in there. In this case, you’ve gotta drop that “n” and make it into a sort of (staccato sounds) I’m a African - make all of the syllables pop.

[MUSIC: “I’m a African:” (Raps: “I’m African and it’s plain to see because I’m gonna be a homo sapiens for life.)]

GELLERMAN: So, what’s next, a Rap Guide to String Theory? A Rap Guide to the Higgs Boson?

BRINKMAN: Well, I’ve got a couple of projects I’ve got a half an eye on but I don’t have anything that I’m 100 percent confirmed. I’ll tell you, one thing I’m interested in doing a rap about is climate change, global warming, environmental sustainability. I think that’s another subject that there’s a scientific consensus on - scientists all agree that yes, the world is getting warmer and yes, it’s human caused to a large degree. There’s not complete agreement on what the political response to that ought to be. That’s one thing I’ve been interested in doing a rap on, although I haven’t been able to figure out how to make that entertaining enough yet, I think, so I’m still taking notes.

GELLERMAN: Well Baba, I love it.

BRINKMAN: Cool. That’s why I make it!

GELLERMAN: Baba Brinkman is the man behind the Rap Guide to Evolution. You can find the link to his songs and his brand new music videos at LOE dot org. Well, Baba, thank you so very much.

BRINKMAN: Thanks for having me on the show, I appreciate it.

Related links:

- See more Evolution music videos

- Listen to the full album here

[MUSIC: “I'm a African.”]

GELLERMAN: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Bobby Bascomb, Eileen Bolinsky, Ingrid Lobet, Helen Palmer, Jessica Ilyse Kurn, Ike Sriskandarajah and Jeff Young, with help from Meghan Miner, Gabriela Romanow and Sammy Souza. Our interns are Annabelle Ford, Christy Perera and Annie Sneed. Jeff Turton is our technical director, Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at Loe.org and check out our Facebook page—it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. Steve Curwood is our executive producer. I’m Bruce Gellerman, thanks for listening.

PRI ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the National Science Foundation, supporting coverage of emerging science. And Stonyfield Farm, organic yogurt and smoothies. Stonyfield invites you to just eat organic for a day: details at justeatorganic.com. Support also comes from you, our listeners, the Go Forward Fund and PaxWorld Mutual and Exchange Traded Funds, integrating environmental, social, and governance factors into investment analysis and decision making, on the web at paxworld.com: Pax World, for tomorrow.

PRI ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth