Extreme Weather-Colorado Floods

Air Date: Week of September 20, 2013

The flooded fields of Boulder high school. (Photo: littlegreenfroggyy)

An unprecedented tropical monsoon dumped more than 17 inches of rain on the Front Range of Colorado, an area which experienced devastating forest fires just last year. Matt Kelsch of the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research in Boulder tells host Steve Curwood that last year’s fires made this year's floods and landslides far more destructive.

Transcript

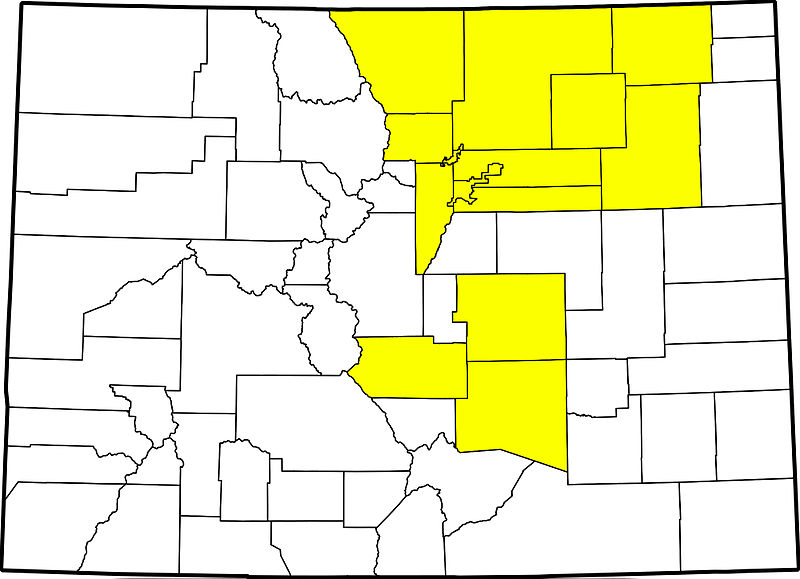

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. First fire, then flood. There were record fires last year in Colorado, and then the record heat at the beginning of this month suddenly broke into a monster monsoon and flooded parts of 17 counties. The torrents killed at least six people, and destroyed or damaged 19,000 homes. The National Weather Service called this latest extreme weather event “biblical”, but to put it in a more scientific context, we called up Matt Kelsch. He’s a hydrometeorologist at UCAR, the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research based in Boulder.

KELSCH: We demolished the old records. Since the European descendants when people moved here and set up rain gauges, we have never seen anything like this. We had about 14.5 inches of rain in three days. The average annual is 20.69. So that’s more than two-thirds of the average annual in three days, and over the entire week, we had 17.2 inches of rain. And the previous wettest year we ever had here had 29.9 per inches of precipitation, and we are up to 30.14 now with three-and-a-half months in the year.

A flooded road in Colorado. (Photo: Nurpu)

CURWOOD: Now, in 2012, we were reporting on the drought out west, and some of the most destructive wildfires in Colorado history. Now I understand that the areas that experienced fires that year are even more susceptible to landslides and perhaps flooding this year. Can you tell me more about that?

KELSCH: Yes, wildfire in the west definitely enhances the potential for flash flooding, and the reason for that is, when it rains, a lot of the water is first captured by the canopy of a healthy forest. So it wets the forest, and then it drips to the ground below, and there’s forest litter - pine needles and decaying leaves - and they act like a sponge that absorbs the water and slow down how it goes into the ground.

When you’ve had a fire, you remove the tree canopy, and you also burn away all that forest litter that’s on the ground. So that water that falls directly on the ground if it’s raining very hard, which it was in this storm. It can’t absorb that quickly and starts running off very quickly to the nearest stream channel, and along with that water running off the surface, it’s carrying all this sediment and debris and sometimes boulders because the land surface is less stable once the trees have been destroyed by fire. So fires definitely increase the risk of flash floods.

CURWOOD: Now, what about these extremes in drought and flooding, and what we might expect from a changing climate?

KELSCH: This flood that we just experienced does have a connection with climate change in that the odds of this kind of event seem to be increasing as the climate changes. It’s not that they were never possible before, but now they’re more possible than they used to be.

Colorado counties declared disaster emergencies by the governor are shaded in yellow. (Wikipedia)

CURWOOD: Now, as I understand it, the first week of September was about the warmest on record for Colorado. What might this warm weather have had to do with these intense rainstorms?

KELSCH: Well, the heat wave, the record heat wave we were having the first week in September probably did have direct correlation with what was to follow. In the western and southwestern United States in particular, there’s something your listeners may have heard of, called the southwest monsoon. Well, what happens is in the mid-to-late summer, typically in July and August, as the surfaces heat up, you have a big heat wave, warm air starts to rise, it creates like a thermal situation where it’s rising, and then tropical air from the Pacific and the Gulf of Mexico can sometimes surge in and cause the set up for the intense rains we see. That’s refered to as the southwest monsoon. But a lot of the biggest floods in the southwest, including Colorado, have been associated with the southwest monsoon, typically in the months of July and August. So this heat wave that we had in September, preceded a very exceptional surge of that monsoon moisture from the tropical Pacific and the Gulf of Mexico. The amounts of rain we had would not have been possible without that exceptional amount of atmospheric moisture.

CURWOOD: Now, of course, humans do change our environment in ways other than the climate. I’m thinking of the built environment - parking lots, roads, and all that. How does things like impermeable surfaces affect this flood?

KELSCH: That’s a really important thing, because when we develop an area, we tend to remove some of the forest and the natural vegetation, which act as a natural buffer to the rain when you do get a flood. And a lot of times, those natural surfaces are replaced with things like buildings and shopping malls and parking lots, and yes, as you indicate, when it rains hard on a parking lot or a building, the water doesn’t go to the ground. All of it just immediately falls off to the nearest stream or low spot, so that also played a role in what we had here, especially in the urban environments - places like Boulder and Aurora, the suburb of Denver, where you had all this urban flooding, just this rapid runoff across the urban environment to the nearest streams that also enhance the flooding that occurred.

CURWOOD: I’ve heard that some homes are isolated now in the wake of this storm...roads washed out. To what extent do you think this event is going to change people’s behavior or opinions about where it’s appropriate to live?

KELSCH: It’s not the first time this has happened. In Colorado, in July 1976, the big Thompson-River Canyon suffered a devastating flood - much more localized than we saw here but just as severe - 144 people died. That same canyon, by the way, was hit in this flood, and also suffered major devastation again. There was a sense back then this was a hundred or a thousand year flood. So I think there is this perception that, “well, that’s never going to happen again.” So I don’t know the answer to your question, but I’d be curious to see if, now that we’ve had another one of these big floods 37 years later, if the perception of risk is going to be a little greater.

CURWOOD: Now, what area were you in when it flooded? Tell me about your own experience.

KELSCH: Well, I live in a neighborhood that wasn’t hit too hard. I did have some flooding in my garage, and it’s a mess, but given that I work in hydrology and meteorology, when I bought my house 23 years ago, I was aware of where the flood plains were. There are some roads in Boulder, actually very close to where I live, just one neighborhood over, where the roads themselves are the designated 100-year floodplain. They’re very steeply sloped roads from west to east, and it’s something you could go to the city’s website, and see that on the website. But most people that live in that area, I’m guessing, didn’t know that. I don’t think real estate agents tell you that when they’re selling a house, and I’m just guessing that a lot of people were totally surprised by the severity of what hit them, even though it’s exactly what the 100-year floodplain map showed was going to happen.

CURWOOD: Matt Kelsch is a hydrometeorologist at UCAR, the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research based in Boulder, Colorado. Matt, thank you so much for taking the time with me today.

KELSCH: Well, thank you.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth