September 20, 2013

Air Date: September 20, 2013

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Extreme Weather-Colorado Floods

View the page for this story

An unprecedented tropical monsoon dumped more than 17 inches of rain on the Front Range of Colorado, an area which experienced devastating forest fires just last year. Matt Kelsch of the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research in Boulder tells host Steve Curwood that last year’s fires made this year's floods and landslides far more destructive. (07:00)

Oil and Gas Wells Under Water

View the page for this story

Weld County Colorado is home to more than 20,000 oil and gas wells, and related storage facilities, and installations have already spilled thousands of gallons of crude onto the flood plain. Todd Hartman of the Colorado Department of Natural Resources explains to host Steve Curwood that assessing the damage and controlling the oil in the surface water are the biggest priorities. (05:55)

Sex and the Single Pest

View the page for this story

Researchers have found a way to manipulate insect mating behavior. This discovery could limit the need for pesticides in the future, if the researchers can limit the effects merely to destructive insects. Poncie Rutsch reports. (01:50)

Power Shift - Energy From Food Scraps

View the page for this story

Massachusetts will ban large businesses and institutions from sending food waste to the landfill. Paul Sellew, CEO of Harvest Power, says this policy could contribute to the green energy revolution. He tells host, Steve Curwood, that the key to turning food waste to power is anaerobic digestion. (07:45)

Small Matters

View the page for this story

The key to many of the biggest mysteries may lie in the smallest of things. Ari Daniel reports that the origins of all life in our universe could come from the tiny chemicals created in clouds between the stars. (05:55)

Birdnote ®/Migration – Long, Short and In-Between

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

Many birds are heading south this month in search of warmer weather. As BirdNote®’s Mary McCann reports, some are long distance travelers, while others head for the hills. (02:00)

Oil and Honey

View the page for this story

Bill McKibben is the closest thing the grassroots climate movement has to a leader, organizing opposition to the Keystone XL pipeline and persuading institutions to divest their holdings from fossil fuels. He sits down with host Steve Curwood to discuss his new book, 'Oil and Honey' — an activist memoir and a meditation on beekeeping in Vermont. (16:45)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

Host: Steve Curwood

Guests: Matt Kelsch, Todd Hartman, Paul Sellew, Bill McKibben

Reporters: Poncie Rutsch, Ari Daniel, Mary McCann

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. The campaign to divest from fossil fuel stocks is gathering pace.

MCKIBBEN: 15 or 16 big cities have already divested: Seattle, San Francisco, Portland. Big religious denominations...the United Church of Christ heard more directly from the Almighty and they said it's not OK to be paying our pastors by investing in companies that are running Genesis in reverse.

CURWOOD: A conversation with Bill McKibben. Also, searching the sky for the origins of life.

LAAS: The first chemical reaction that takes place in the universe is actually just the formation of molecular hydrogen. Once you get these clouds, they’ll become thick enough that they'll help shield the contents to form more rare molecules.

CURWOOD: We'll have that and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm. Makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

Extreme Weather-Colorado Floods

The flooded fields of Boulder high school. (Photo: littlegreenfroggyy)

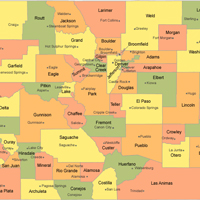

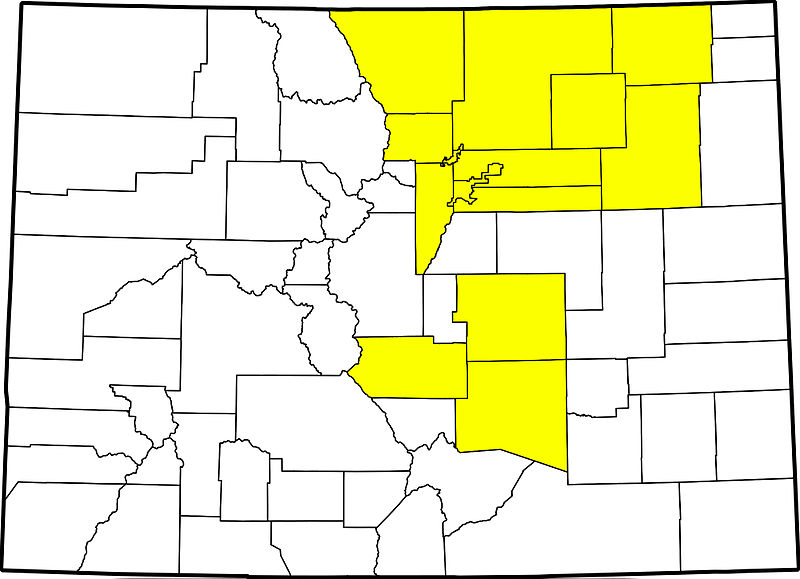

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. First fire, then flood. There were record fires last year in Colorado, and then the record heat at the beginning of this month suddenly broke into a monster monsoon and flooded parts of 17 counties. The torrents killed at least six people, and destroyed or damaged 19,000 homes. The National Weather Service called this latest extreme weather event “biblical”, but to put it in a more scientific context, we called up Matt Kelsch. He’s a hydrometeorologist at UCAR, the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research based in Boulder.

KELSCH: We demolished the old records. Since the European descendants when people moved here and set up rain gauges, we have never seen anything like this. We had about 14.5 inches of rain in three days. The average annual is 20.69. So that’s more than two-thirds of the average annual in three days, and over the entire week, we had 17.2 inches of rain. And the previous wettest year we ever had here had 29.9 per inches of precipitation, and we are up to 30.14 now with three-and-a-half months in the year.

A flooded road in Colorado. (Photo: Nurpu)

CURWOOD: Now, in 2012, we were reporting on the drought out west, and some of the most destructive wildfires in Colorado history. Now I understand that the areas that experienced fires that year are even more susceptible to landslides and perhaps flooding this year. Can you tell me more about that?

KELSCH: Yes, wildfire in the west definitely enhances the potential for flash flooding, and the reason for that is, when it rains, a lot of the water is first captured by the canopy of a healthy forest. So it wets the forest, and then it drips to the ground below, and there’s forest litter - pine needles and decaying leaves - and they act like a sponge that absorbs the water and slow down how it goes into the ground.

When you’ve had a fire, you remove the tree canopy, and you also burn away all that forest litter that’s on the ground. So that water that falls directly on the ground if it’s raining very hard, which it was in this storm. It can’t absorb that quickly and starts running off very quickly to the nearest stream channel, and along with that water running off the surface, it’s carrying all this sediment and debris and sometimes boulders because the land surface is less stable once the trees have been destroyed by fire. So fires definitely increase the risk of flash floods.

CURWOOD: Now, what about these extremes in drought and flooding, and what we might expect from a changing climate?

KELSCH: This flood that we just experienced does have a connection with climate change in that the odds of this kind of event seem to be increasing as the climate changes. It’s not that they were never possible before, but now they’re more possible than they used to be.

Colorado counties declared disaster emergencies by the governor are shaded in yellow. (Wikipedia)

CURWOOD: Now, as I understand it, the first week of September was about the warmest on record for Colorado. What might this warm weather have had to do with these intense rainstorms?

KELSCH: Well, the heat wave, the record heat wave we were having the first week in September probably did have direct correlation with what was to follow. In the western and southwestern United States in particular, there’s something your listeners may have heard of, called the southwest monsoon. Well, what happens is in the mid-to-late summer, typically in July and August, as the surfaces heat up, you have a big heat wave, warm air starts to rise, it creates like a thermal situation where it’s rising, and then tropical air from the Pacific and the Gulf of Mexico can sometimes surge in and cause the set up for the intense rains we see. That’s refered to as the southwest monsoon. But a lot of the biggest floods in the southwest, including Colorado, have been associated with the southwest monsoon, typically in the months of July and August. So this heat wave that we had in September, preceded a very exceptional surge of that monsoon moisture from the tropical Pacific and the Gulf of Mexico. The amounts of rain we had would not have been possible without that exceptional amount of atmospheric moisture.

CURWOOD: Now, of course, humans do change our environment in ways other than the climate. I’m thinking of the built environment - parking lots, roads, and all that. How does things like impermeable surfaces affect this flood?

KELSCH: That’s a really important thing, because when we develop an area, we tend to remove some of the forest and the natural vegetation, which act as a natural buffer to the rain when you do get a flood. And a lot of times, those natural surfaces are replaced with things like buildings and shopping malls and parking lots, and yes, as you indicate, when it rains hard on a parking lot or a building, the water doesn’t go to the ground. All of it just immediately falls off to the nearest stream or low spot, so that also played a role in what we had here, especially in the urban environments - places like Boulder and Aurora, the suburb of Denver, where you had all this urban flooding, just this rapid runoff across the urban environment to the nearest streams that also enhance the flooding that occurred.

CURWOOD: I’ve heard that some homes are isolated now in the wake of this storm...roads washed out. To what extent do you think this event is going to change people’s behavior or opinions about where it’s appropriate to live?

KELSCH: It’s not the first time this has happened. In Colorado, in July 1976, the big Thompson-River Canyon suffered a devastating flood - much more localized than we saw here but just as severe - 144 people died. That same canyon, by the way, was hit in this flood, and also suffered major devastation again. There was a sense back then this was a hundred or a thousand year flood. So I think there is this perception that, “well, that’s never going to happen again.” So I don’t know the answer to your question, but I’d be curious to see if, now that we’ve had another one of these big floods 37 years later, if the perception of risk is going to be a little greater.

CURWOOD: Now, what area were you in when it flooded? Tell me about your own experience.

KELSCH: Well, I live in a neighborhood that wasn’t hit too hard. I did have some flooding in my garage, and it’s a mess, but given that I work in hydrology and meteorology, when I bought my house 23 years ago, I was aware of where the flood plains were. There are some roads in Boulder, actually very close to where I live, just one neighborhood over, where the roads themselves are the designated 100-year floodplain. They’re very steeply sloped roads from west to east, and it’s something you could go to the city’s website, and see that on the website. But most people that live in that area, I’m guessing, didn’t know that. I don’t think real estate agents tell you that when they’re selling a house, and I’m just guessing that a lot of people were totally surprised by the severity of what hit them, even though it’s exactly what the 100-year floodplain map showed was going to happen.

CURWOOD: Matt Kelsch is a hydrometeorologist at UCAR, the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research based in Boulder, Colorado. Matt, thank you so much for taking the time with me today.

KELSCH: Well, thank you.

Related links:

- USGS on the Colorado Floods

- UCAR

[MUSIC: Elvis Costello & The Roots “Cinco Minutos Con Vos” from Wise Up (Ghost) (Blue Note Records 2013)]

Oil and Gas Wells Under Water

Weld County in the northeastern portion of the state is ground zero in Colorado for oil and gas production, agriculture, and this year’s flood.

CURWOOD: As the water recedes, authorities are scrambling to assess the extent of the damage. Weld County, northeast of Boulder, is the state’s leading agricultural producer, and also its second largest producer of gas and oil. Aerial photos of the area show several drilling platforms and oil

tanks toppled or washed away in the flood. Todd Hartman is with the Colorado Department of Natural Resources.

HARTMAN: There are about 20,000 active oil and gas wells in Weld County. Now that’s not to say that many wells have been impacted by this event, but surely I think it’s safe to say we’ve had hundreds of sites affected one way or the other.

CURWOOD: So what types of contaminants are in the area that could find their way into the environment as a result of this flood?

HARTMAN: To answer that question broadly, there are a number of municipal sewage treatment plants that have already been affected, there are enormous agricultural activities, so you have anything from pesticides, herbrbicides, and the sort of large diesel storage tanks that you might see on a lot of farms. And, of course, as you point out, you have a great deal of oil and gas development.

More than anything you have tanks and wellheads that capture the oil that comes up from the ground, and the tanks store the oil - it’s crude oil. A lot of folks have expressed concern specifically about fracturing chemicals, chemicals used in the hydraulic fracturing process; the number of sites that may have actually been fracking going on when this flood occurred is anywhere from few to perhaps zero. I think that’s still being sorted out. So, I guess my major point here is, that’s not to downplay the issue at all, because we do have crude oil stored in tanks at many of these sites, and clearly you don’t want that escaping into the environment.

A truck is washed away in Longmont, Colorado. (Photo: Nurpu)

CURWOOD: Yes, there are pictures one can see of the oil tanks toppled over, the drilling platforms destroyed. How large a concern do you have there that the oil spills could turn out to be a widespread problem, and how resistant are these wells to flooding situations?

HARTMAN: Generally speaking, those are double-walled tanks, and they’re pretty robust, but that’s certainly not to suggest that they would be immune to problems here. We do have concerns about the scenes you’ve described, and we’re out there now to get a sense of whether this is a widespread problem. We don’t know quite enough yet to say with any certainty this is either a very small impact or a very large impact.

CURWOOD: How concerned are you the contaminants might be finding their way into groundwater, which could potentially, of course, become a public health problem?

HARTMAN: That’s absolutely a concern. I’m no hydrologist, and I’m not a scientist and so I hestitate to make this point, but I would say, since you specifically asked about groundwater, initially, if you did have a problem, this is going to be carried in surface waters, and surface waters would be the most immediate concern. I think over a longer period of time, as the waters recede, and we have a better sense of water occurred, we will be looking at groundwater impacts and trying to determine what the impacts on groundwater are. But I think our immediate concern here is the more obvious and visible impacts.

CURWOOD: What about the question of sediment contamination in the weeks, months, years ahead? There’s a lot of agriculture there in Colorado. How might farmers, ranchers be affected, be concerned about pollution on their land following this great flood?

HARTMAN: Well, I think they should be very vigilant about that. We are taking it seriously. We, like the farmowners and landowners will want to know about that. We will be looking for it ourselves because it’s in nobody’s interest to have sediments, soil contamination or groundwater contamination. We all benefit from the agriculture that takes place in that region, and, in fact, all that food is consumed here in the Denver Metro area so there’s a high level of awareness there.

CURWOOD: I’m wondering, if, in the future, the experience of this flood might affect how you handle permitting for oil and gas wells.

HARTMAN: Well, I think anytime something out of the ordinary like this happens, it’s an opportunity to ask ourselves, can we do better? Is there a regulatory approach that needs to be reviewed here? By the same token, you have to balance that with the idea, this is, at least at this point in our state’s history, an extremely unusual event, and do you build regulations around an event this unusual or is there some middle ground you reach? Doubtless we will be examining closely what occurred here, what the impacts were, and whether there are things we can do in our regulatory capacity to address this if it were to occur in the future and reduce those impacts. But it’s awfully early for us to be thinking about that when we still don’t fully understand what the impacts were.

CURWOOD: Well, good luck sort of seems lame compared to what you’re up against.

HARTMAN: [LAUGHS] Well, I appreciate the sentiment. It’s good to speak about it with you.

CURWOOD: Todd Hartman is a spokesman with the Colorado Department of Natural Resources. Thanks so much, Todd.

HARTMAN: Thank you very much.

Related link:

Colorado Department of Natural Resources

[MUSIC: Bill Frisell “The Big One” from Big Sur (Savoy Jazz 2013)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...how the food we throw away could power our homes for the future. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Azule Serape” from Azule Serape (Impressions 1961) Happy Birthday Julian Cannonball Adderley (9/15/1928 – 08/08/1975)]

Sex and the Single Pest

The researchers also tested silkworm moths to see how the natalisin knock out impacted their reprodcution. They learned their research decreases reproduction of all insects tested – not just pest species. (Photo: Big Stock Photo)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. Just ahead, exploring very big concepts by contemplating the night sky. But first this note on emerging science from Poncie Rutsch.

RUTSCH: For decades, farmers have used noxious pesticides to kill insects that eat crops. But environmentalists complain that these pesticides run off from farms, contaminating the soil, lakes, and streams.

This pest control could change, though. Yoonseong Park, a professor of entomology at Kansas State University, has found a way to manipulate insects’ sexual activity.

Park worked with colleagues in Korea and Slovakia to identify a signaling chemical called natalisin, a cluster of amino acids that tells the brain to commence mating behavior. He knocked out natalisin in three different kinds of insects: fruit flies, silk worm moths, and a species of beetle.

Park reports that when natalisin isn’t present, the insects’ mating rituals didn’t quite work. The beetles lacking natalisin only managed to produce a quarter of their typical offspring. And the fruit flies struggled in their mating rituals – the male sang his typical mating song to an appealing female, but the sound came out much quieter than usual…and the female was too busy grooming herself to notice him!

Park and his colleagues tested their mating ritual manipulation on red flour beetles, a pest insect that plagues cereal silos. They are well adapted to dry environments and can withstand higher amounts of radiation than several species of cockroach. (Photo: Duncan Hull, via Flickr Creative Commons)

The findings suggest an environmentally safe technique to manage pests – birth control. But Park has yet to find a way to target a single species or even small groups of species. He says this method must be pursued cautiously, to limit the impacts just to pests. After all, there are plenty of pollinators and scavengers that he wouldn’t want to interrupt!

That’s this week’s note on emerging science. I’m Poncie Rutsch.

Related links:

- Sex and the Single Pest

- Yoonseong Park

Power Shift - Energy From Food Scraps

Harvest Power’s soil and mulch products (photo: Harvest Power)

CURWOOD: As part of its renewable energy program, Massachusetts will ban large institutions from sending food waste to the dump. Starting next July, major facilities must either compost their scraps, or send them to an anaerobic digester. Paul Sellew is the CEO of Harvest Power, a company that plans to run anaerobic digesters to convert thousands of tons of food waste to energy in Massachusetts. Sellew stopped by our studios to explain how he thinks food waste bans will help us take full advantage of the renewable energy source on our plates. Welcome to the show.

SELLEW: Great to be here!

CURWOOD: Paul, tell us about this food waste ban in Massachusetts. Just how would this work?

SELLEW: Well, it’s really straightforward. If you are a commercial generator of food waste, say a large restaurant, an institution, a university, a grocery store, then basically the legislation is around incenting and requiring you to put that to a higher and better use, versus sending it to a landfill or sending it to an incinerator which is where about 97 percent of the food waste is being disposed of right now in Massachusetts and, for that matter, the United States.

CURWOOD: It’s a rulemaking rather than legislation?

Paul Sellew, CEO of Harvest Power (photo: Harvest Power)

SELLEW: Yes, it’s rulemaking because you need to build out the infrastructure, and it’s a little bit of a chicken and egg issue, right? You need to have feedstock to build out the facility such as anerobic digestion and composting, and then you also need this infrastructure to be built so that you have a place to take the food waste that’s being generated.

So I think it’s very pragmatic and practical way to incent companies and incent generators to basically to do the right thing for the environment.

Harvest’s Energy Garden in Richmond, British Columbia (photo: Harvest Power)

SELLEW: So, how much food waste is there in Massachusetts where you operate your company?

SELLEW: DEP says about a million tons a year. So, if you look at it as a country, you multiply that by about 40, and that’s how much we have as a country, about 40 million tons, so enormous amounts of material. And basically, it’s a great feedstock for anerobic digestion, and or composting, and it is such a better use of the material than sending it to a landfill or an incinerator where you end up losing the value inherent in this material.

CURWOOD: Describe the process for us. How do you turn food waste into energy we can use?

Feedstock, food scraps and yard trimmings (photo: Harvest Power)

SELLEW: Well, the way we do it is that we borrow from nature, and scientists call this biomimickry. So a great example of a natural living anerobic digester is a ruminant - a cow, a sheep or a goat. They are basically operating anerobic digesters in their gut, and that’s why they can eat things such as grass and hay that we can’t eat. And literally we are mimicking the biological processes that go one in the stomach of a ruminant with one difference.

CURWOOD: And that is?

Anaerobic digesters (photo: Harvest Power)

SELLEW: We capture the biogas. Basically, it does not go into the atmosphere. It is captured, and biogas is about 65 to 70 percent methane, and methane is natural gas. So we capture and use that as a source of renewable energy which is a very obviously important part of our process.

CURWOOD: So how do you deliver the energy from this biogas to customers, let someone use it to turn on their lights?

SELLEW: Well, that’s a great question. We can put it into an onsite engine genset called a combined heat and power made by companies like Caterpillar and General Electric, and we basically can substitute, say, natural gas for diesel fuel or even gasoline, use biogas as the fuel, run this; that powers an electric genset, and that’s hooked right up to the grid, and then we in turn enter into a power purchasing agreement with the utility, and they buy the electricity we’re generating from our facility on a 24/7 basis. The other flexible uses for biogas is it’s about 65 percent methane; the balance is CO2. You can strip off the CO2, enrich the biogas now to what we call a biomethane, which is an identical product to natural gas. Once you’ve done that, you can put it into the natural gas grid. You can also compress it, and make what we call bio-CNG, or bio-compressed natural gas, which is a transportation fuel. So you’ve got a fuel that can be used for electricity, can be used for anything that natural gas is used for, and can also be used as a transportation fuel, and that also is available on a 24/7 basis because once again, we’ve captured the energy in the plant material. So unlike my friends in the wind and solar business, that are depending on the wind blowing or the sun shining, we basically are what we call base load power, so we’re available 24/7.

CURWOOD: You do depend on people eating regularly though.

SELLEW: [LAUGHS] Absolutely, and we’re quite confident that practice will continue.

CURWOOD: So, how much power can you generate with this?

SELLEW: Well, if you figure roughly three to four tons of basically of our input - food waste - things we would ordindinarily throw into a landfill, that will generate enough electricity to power an average home for one month.

CURWOOD: So how how soon will we be seeing one of these plants in Massachusetts?

SELLEW: Well, we have anerobic digesters right now in Massachuetts, facilities like Deer Island, and as part of the wastewater treatment infrastructure that many communities have in Massachusetts. So anerobic digestion is not a new technology. In fact, it’s quite common in the wastewater treatment field. What is new about what Harvest is proposing is the application of that technology to new organic waste streams, such as food waste, such as leaves, grass and brush. That is what’s new. I think Massachusetts will be at the forefront of this new type of renewable energy.

CURWOOD: How about Harvest Power? How soon for you?

SELLEW: Well, we’re quite active, so, I mean, we hope very soon. There’s significant environmental regulations and permitting. These facilities are not uncomplicated to develop, and they take time. So based on going through all the hurdles, we would hope to have an operating facility within a few years.

CURWOOD: You know, this sounds...well somebody listening to us might say, this sounds too good to be true. What’s the catch here?

SELLEW: Well, let’s look at a country, the fourth largest economy in the world, Germany. The largest form of renewable energy in Germany is from organic materials, principally through anerobic digestion. We have a large renewable energy industry, also using organic materials, but what we have elected to do in this country is to grow a corn plant, and take the corn kernels off that plant and turn it into ethanol. That is not the sustainable thing we should be doing.

Now, in Germany, they’ll take the cob, the kernels, the entire plant, and because we break down cellulose and hemi-cellulose, starches and sugars in an anerobic digester, you get about three to four times the energy per acre putting that corn plant through an anerobic digester. The Germans looked at this from a science base, and they did policy accordingly. We did it on a politic base analysis that our elected representatives decided to do something for the corn growers.

So I think we eventually will do the right thing, but I take great excitement seeing what a country like Germany has done where they have been close to building 1,000 anerobic digesters per year, and having much larger industry around anerobic digestion in Germany, and they’re one-fourth the size of the U.S. economy.

CURWOOD: Paul Sellew is the CEO of Harvest Power, a Massachusetts based company that makes anerobic digesters. Thanks for coming by, Paul.

SELLEW: Thank you.

Related links:

- Harvest Power website

- Watch Paul Sellew’s TEDtalk

[MUSIC: Flimm & The BB’s “Lunch Hour Wedding march” from Tricycle (DMP records 1983)]

Small Matters

CURWOOD: The key to the most profound realities of our existence may not be found on our world at all. It’s still a subject for speculation and conjecture, but the origin of life on Earth may well be unearthly, and the whole unbounded diversity of existence here may have seeds far, far away. At least, that’s a possibility that Ari Daniel found himself considering, as he contemplated what exactly is to be found in distant clouds across the universe. His story is part of a series called “Small Matters”, where he sweats the small stuff; in this case, seeking the world in a handful of stardust.

DANIEL: If someone were to offer to meet me in a dark, deserted parking lot in the middle of the night, I’d probably think twice. But I didn’t even bat an eye when Jacob Laas suggested it to me because that was the whole point of our rendezvous...the darker, the better. And that’s because LAAS is a stargazer.

LAAS: Just the expanse of the universe is just amazing, almost incomprehensible to what we’re used to on our day-to-day lives. And so when I look up, I just take it all in.

DANIEL: This parking lot is on the campus of Emory University in Atlanta where Laas is a graduate student in astrochemistry.

LAAS: It’s a good night. Beautiful here.

DANIEL: LAAS studies the molecules of outer space, and how those molecules may have shaped our galaxy and life itself. But first things first - we need to get our eyes on the sky.

[CAR TRUNK POPS OPEN]

DANIEL: Laas pops open the trunk to his Jeep to reveal his personal treasure.

LAAS: I’ve had this telescope I think since I was about 10 now. You know, I convinced my dad into getting it for me.

DANIEL: This isn’t your average handheld telescope. The whole setup weighs a good 70 pounds. It takes Laas 15 minutes to assemble it in the cold night air. First come a hefty tripod and mounting platform, which secure the actual telescope - a black cylinder the size of a small trash can. Finally, Laas screws a couple counterweights into position.

LAAS: Alright, so everything’s set up.

DANIEL: Laas spins the telescope effortlessly, the counterweights balancing every turn.

DANIEL to LAAS: I feel like you’re playing an instrument.

LAAS: An instrument in the dark.

DANIEL: To get things started, he swivels the telescope towards the half moon. Even from a couple feet away, I can see moonlight streaming out of the eyepiece.

LAAS: Yeah, do you wanna have a look?

DANIEL: I’d love to. Wow, it’s beautiful.

LAAS: Once you have a couple looks at one of these things, it’s easy to fall in love with the astronomy.

DANIEL: But we’re not out here tonight to look at the moon, as pretty as it is. We’re after something much less obvious. Laas ratchets up the magnification, and swings the telescope towards the bottom of Orion. He scans the constellation slowly until he finds a patch of soft blue mist, something called...

LAAS: The Great Orion Nebula.

DANIEL: And within this nebula, it looks like dark holes have been punched out of the mist. These chunks of darkness are what we’re looking for - interstellar clouds - dense accumulations of gas and dust that sit between stars. The reason that Laas studies these clouds, usually with much more powerful telescopes - is because they’re the site of some pretty remarkable chemistry.

LAAS: The first chemical reaction that takes place in the universe is actually just the formation of molecular hydrogen.

DANIEL: That is, hydrogen gas, or the stuff that exploded so disastrously on the Hindenburg. And hydrogen gas first gets formed inside these interstellar clouds.

LAAS: And so once you get these clouds that start to form more molecular hydrogen, they’ll become thick enough that they’ll help shield the contents to form more rare molecules.

DANIEL to LAAS: Shielding from what?

LAAS: Cosmic rays...

DANIEL to LAAS: So molecules have trouble forming in the universe because they’re being bombarded by this stuff?

LAAS: Yeah, they’re constantly being bombarded by particles or photons that otherwise would just rip them apart.

DANIEL: The interstellar clouds, puffed up with hydrogen gas - provide a kind of protective blanket for other molecules to form, and remain intact.

LAAS: You can start to get CO.

DANIEL to LAAS: Carbon monoxide.

LAAS: Yeah, carbon monoxide. Then you start to see methanol.

DANIEL: The simplest alcohol there is. Gradually, these interstellar clouds get warmer and build up an inventory of molecules. And it’s thought that this process may have seeded the early galaxies - over 13 billion years ago - with a set of chemical building blocks that helped to form meteors, and asteroids, and planets. And even, perhaps, molecules tied to the origin of life.

LAAS: Well, there’s another molecule called glycolaldehyde that is almost a sugar.

DANIEL: That almost sugar is made inside interstellar clouds too, and it’s been shown to give rise to the more complex sugars we see in living organisms today.

Now, this next bit is somewhat speculative, but hear me out. There’s some debate as to whether these clouds are the birthplace of comets - we just don’t have enough information to be sure. But if it’s true, then comets could act as a kind of delivery vehicle for these molecules to get out of the interstellar clouds and end up on planets, like Earth. And since comets are full of ice, we may have interstellar clouds to thank for the watery, life -filled world we see around us.

And this is what captures LAAS’ imagination...

LAAS: That what goes on right in front of us can also occur everywhere else out in the universe that we look at. It’s exciting to me to be able to make these connections between these two extremes.

DANIEL: All you need, says Jacob Laas, is a big telescope to look deep into outer space...and an even bigger amount of ambition, right here on Earth.

For Living on Earth, I’m Ari Daniel.

CURWOOD: Our series, Small Matters, is produced by the Center for Chemical Evolution, with support from the National Science Foundation and NASA.

Related links:

- National Science Foundation

- Small Matters

[MUSIC: Bonobo “Don’t Wait” from The North Borders (Ninja Tune 2013)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...oil, honey, and revolution. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment. Supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Outer Bridge Ensemble: “Determined” from Determined (Outer bridge Music 2013)]

Birdnote ®/Migration – Long, Short and In-Between

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood.

[BIRD NOTE® THEME]

Arctic Terns fly south from Alaska to Antarctica. (Photo: Tom Grey©)

CURWOOD: It's just past the autumnal equinox, and now the days are shorter than the nights and the infallible signs of approaching winter are all around us. Still, this season does offers the joys of fall - here in the north, the harvest, the turning leaves and the departing birds. Here's Mary McCann with our BirdNote®.

MCCANN: In September, Arctic Terns fly south over the ocean, from Alaska all the way to Antarctica.

[ARCTIC TERNS’ GRUFF CALLS]

MCCANN: Also in September, the last Rufous Hummingbirds depart their breeding range in the West, following “floral highways” of mountain wildflowers south to Mexico.

[MALE RUFOUS HUMMINGBIRD WING-WHISTLE]

MCCANN: Ruby-crowned Kinglets are leaving the northern evergreen forests where they nest, on their way to milder climates.

[RUBY-CROWNED KINGLET SONG]

MCCANN: Each of these birds is migrating, but on a very different course. All have the same adaptive goal – making the most of food and breeding opportunities that change with the seasons. Arctic Terns follow one of the longest annual migrations, traveling as much as 44,000 miles each year. Arctic tundra provides their ideal nesting site in summer, the Antarctic, the ideal feeding grounds in our winter.

[ARCTIC TERNS’ GRUFF CALLS]

The Rufous Hummingbird follows the wildflowers on its way south.(Photo: Tom Grey ©)

MCCANN: Rufous Hummingbirds are medium-range migrants, traversing about 5,000 miles a year between temperate and tropical nectar sources.

[MALE RUFOUS HUMMINGBIRD WING-WHISTLE]

MCCANN: Some Ruby-crowned Kinglets are altitudinal migrants, especially in the West. They may remain close to the same latitude all year, but spend the cold months in the relative warmth of the lowlands dining on insects and their eggs. In summer, you’ll need to ascend thousands of feet into the western mountain ranges to hear the kinglet’s exuberant song.

I’m Mary McCann

[RUBY-CROWNED KINGLET SONG]

CURWOOD: To find some photos, migrate over to our website LOE.org.

Related links:

- Bird audio provided by The Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Arctic Tern calls, Ruby-crowned Kinglet song and Rufous Hummingbird call recorded by G.A. Keller. Ambient songbird track recorded by C. Peterson.

- BirdNote® “Migration – Long, Short, and In-Between” was written by Bob Sundstrom.

[MUSIC: John Coltrane “Equinox” from Coltrane’s Sound (Atlantic Records 1960)]

Oil and Honey

A beekeeper at work (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: In early 2011, the Keystone XL Pipeline Project to bring tar sands crude from Canada to refineries on the US Gulf Coast seemed almost certain to be approved by the State Department, and the White House.

Now that approval's no longer quite such a slam-dunk, and part of what's changed the equation are protests organized by 350.org. In all, more than 1,000 people opposed to the project were arrested on the steps of the White House in the fall of 2011, setting off a fierce national debate on climate change.

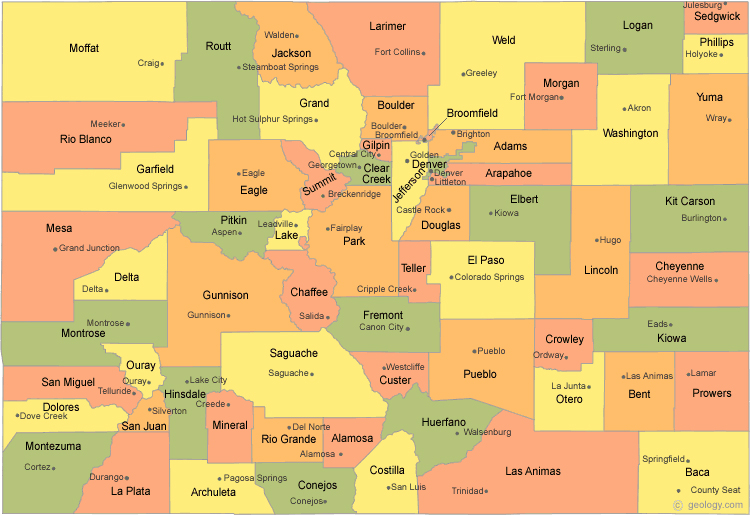

Among those arrested was Bill McKibben, a co-founder of 350.org. His new book, Oil and Honey, is part memoir of the life of a climate activist, and part meditation on beekeeping in Vermont. Bill, welcome back to Living on Earth.

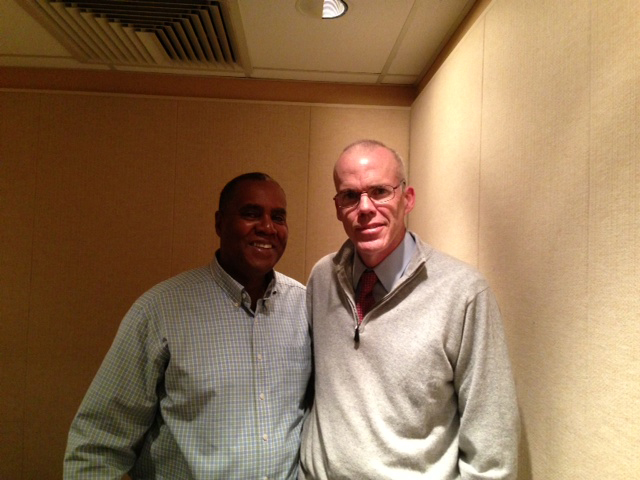

Bill McKibben speaking at a presentation on fossil fuel divestment (photo: Steve Liptay)

MCKIBBEN: Steve, as always it's awfully good to be with you.

CURWOOD: So, Oil and Honey, kind of a bibical reference? What’s this book all about.

MCKIBBEN: Well, I suppose it’s a title that works in a lot of ways. It either calls up those bibical ideas of milk and honey or the idea of oil and water not mixing or whatever, but it’s about the global and the local. Oil stands for the global problem in which we’ve fallen - the greatest problem that humans have ever faced. The honey, and the story about the beekeeper in Vermont, that underlies half of the book, reminds us that it’s possible to imagine a different world, that that world is the one we need to head toward. The reason we have to head off the climate crisis is so we can produce the kind of planet that works for people and works for the rest of creation too.

Oil and Honey by Bill McKibben

CURWOOD: This book is a delight to read, and it’s, well, much more personal that your other books, although you did write about just having one child, having only one. This is really a memoir about your personal transformation from Bill McKibben, the environmental writer to Bill McKibben, the rabble-rousing, getting arrested activist. At what point did you decide that being a commentator about climate issues just wasn’t going to cut it anymore?

MCKIBBEN: You know, I wrote the first book about global warming 25 years ago now, The End of Nature, and at the time, I think I and probably most people thought, “This is an argument about reason and science, and as that science becomes clear to everybody, well then, change will follow, that our leaders will do what’s necessary.” And for year after year, scientists trotted up to Capitol Hill and explained that the worst thing that ever happened is happening, and economists came up behind them and said it’s pretty clear what we need to do; we put a price on carbon to reflect the damage it does in the atmosphere; we’ve internalized the externalities; we won the scientific and economic arguments powerfully; we just weren’t winning any action; we were losing the war.

And at a certain point I think a bunch of us realized, this isn’t about reason. It’s mostly about the incredible power of the fossil fuel industry - they’re the richest industry on Earth. I mean, Exxon made more money the last four years than any company in the history of money, OK? And if we were going to take them on, it wasn’t enough to just win the scientific argument, to write some more books, wasn’t going to substantially contribute to this. We needed to build a movement that could find a different currency than money to work in; the currencies of movement, passion, spirit, creativity. Sometimes we’d need to spend our bodies.

Bees dancing (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: One of the gifts of your book, Bill, is you take us inside this massive demonstration in 2011, really, several days of demonstration action in Washington where you and a number of prominent people get arrested, including Gus Speth, who used to run the Presidential Council on Environmental Quality, a guy with a White House pass gets arrested in front of the White House. Tell us how that all came about.

MCKIBBEN: Well, we’d sent out a letter, Gus - myself and Wendell Berry and some others asking people to come to Washington and get arrested, with the start of this protest over the Keystone Pipeline. And we did not know if anyone would show up, but a lot of people showed up even on the first day of this planned, two-week thing. There were about 100 people there to get arrested. So the police decided they’d try to deter us by treating us somewhat more harshly than they normally do protesters.

The first wave of us got to spend three days in a central cell block in DC, which is about as much fun as it sounds like it would be. But the great pleasure was having Gus in the next cell through the bars, and we could talk. In fact, he shouted out a half hour synopsis of his new book America the Possible to the whole cell block - all the other protestors who were there were - kind of a jailhouse school, you know?

Keystone XL protesters in San Francisco (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

I remember at one point, they weren’t letting us out to see lawyers or anything. Well, Gus Speth’s son was a big heavy duty corporate lawyer in DC, and he’d been papering the jailhouse with writs I think and things, and finally they let Gus out to see his son for a few minutes. And we knew that was our chance to send a message to the press so we tried to think what Gus could say, and he just wrote out this one sentence - you’re right, he had been head of the Council on Environmental Quality, head of the UN Development Program, he’s pretty much as heavy a hitter as there had ever been - and the one sentence he wrote was, “I’ve held a lot of important positions in this town, but none of them seem as important as the one I’m in right now.” Which I thought was a pretty powerful way to explain why movements are really what underwrites all the other environmental policy and investigation and things that we engage in.

CURWOOD: So, three nights in jail, and not just any jail, but DC, downtown, pretty nasty place. I mean, one has to think it’s DC, that the White House would have had some influence over this decision.

MCKIBBEN: Oh, no, no, frankly, I kind of doubt it. I bet they weren’t paying that much attention, at least at the beginning, but they’re paying attention now. Keystone’s become the iconic environmental fight of our time, and sometime this year or next, the President’s going to have to make the call, and when he does, it’ll be an interesting moment. If he does the right thing and blocks it, it’ll be the first time any world leader has ever said ‘no’ to a big project on the grounds that it would be bad for the climate. If he says ‘yes’, I fear that we’ll have no choice but to think of him, at least on this issue, as big talk small action.

CURWOOD: Ah, Bill, you could have easily chosen to write a memoir exclusively about your work with 350.org, but it’s called Oil and Honey, and you spend an awful amount of time writing about your friend whose running an apiary - bee business - down in the Champlain Valley of Vermont. Why was it important to tell us about you and your friend’s relationship with honey?

MCKIBBEN: Well, first of all, this guy is a great character, Kirk Webster; first chemical-free commercial apiarist in the country, his hives thriving, despite the horrible things happening to honeybees ,as you know is happening across this planet, so I wanted to tell his story. But the more that I thought about it, the more it was clear to me, that this was the other half of the story that needed telling.

We need to do two things. We need to make our local places work again, to be able to be more self-reliant, to not depend on supply lines that stretch out forever in the world, but relocalize much of our lives. There’s no way to break the fossil fuel habit without doing some of that, and that’s why it’s beautiful to watch these things happen, and I love to describe the time with the bees and things.

Bill McKibben with host Steve Curwood in the Living on Earth studio. (Emmett FitzGerald)

By the same token, if that’s all we do, then it won’t work. There we were in Vermont in 2011, in beautiful bucolic Vermont, when Hurricane Irene came up the East Coast and passed over record warm waters off New York and New Jersey and soaked up immense amounts of rainfall and shattered every record that we had in Vermont for rain and it just washed away, not just roads and bridges, it washed away a lot of the beautiful organic farms. We’ve got to do both these things - local, global, home and away.

CURWOOD: One of the things you note about bees is their decisionmaking. You say this is a form of consensus.

MCKIBBEN: This fascinating book, about a year old, by a Cornell entomologist named Tom Seal and his question was how do bees...bees swarm in the spring...if they get too many in a hive, half the hive will go and find a new home. You’ve seen them sometime, big colonies of bees hanging from a lightpost or tree. They’re waiting for 48 hours to figure out where their new home will be. It’s not that the queen goes and makes a decision - just the opposite - she’s a bystander.

When that swarm emerges, hundreds of scouts go off in every direction, and they find suitable-sized holes and trees or under eaves and things, and they come back to the swarm and they tell the story. They do it by dancing to sort of describe the place they found and where it is, and the ferocity of the dance indicates how good they think it is. So if they’re really, serious, like Soul Train, then a lot of the bees start paying attention. Some of them go off and look at that hive, and they come back and if they agree, they’ll dance enthusiastically.

There’ll be six or seven contenders at first, and then more and more bees will go stand in one corner, as it were. When you get to about 60 or 70 percent, the whole thing just tips, and everyone agrees, and they fly off together. So it’s a lot like a New England Town Meeting, you know? Very direct democracy. And as far as one can tell, uncontaminated by...I mean, there’s no bees buying off other bees in order to get things to go their way. So yes, a useful reminder of what a more direct form of democracy looks like.

CURWOOD: OK, Bill, when you began 350.org, it seemed you were really focused on the political process, going after politicians to make a change. When did you decide to aim straight at the oil companies?

MCKIBBEN: Well, because we figured out that the politicians were not independent actors in this case. When we’ve watched the Keystone thing, we can predict with unerring accuracy how politicians, how congressmen will vote. If you tell me how much money they took from the fossil fuel industry, I can tell you how they’ll vote on virtually anything related to the energy industry. So we really began to understand that these guys were the problem. And it’s why we’ll play defense with things like Keystone, but why not try to play offense as hard as we can, especially with this divestment campaign that’s burgeoning around the country and very exciting to me.

CURWOOD: Let’s talk about divestment. You’ve been out there, fighting against Keystone, but now you’ve moved into this realm of asking to divest of their investments in fossil fuels.

MCKIBBEN: We focused first of all, on institutions, on colleges, on universities, churches, cities. We started about 10 months ago modeling ourselves really on the work that was done around apartheid in South Africa a generation ago, and it was Desmond Tutu who played such a role in that fight that recorded the seminal video for this. He said if you could see what drought and famine were doing to Africa through no fault of our own, you’d understand why we need you to take up the same tools again.

So far, beginners luck, we’re ahead of the pace of, say, the work on South Africa. 15 or 16 big cities have already divested: Seattle, San Francisco, Portland, Providence, Rhode Island. Six or seven colleges have already done so, most recently San Francisco State. This summer, big religious denominations...Unitarians said they’re going to spent a year in the process of discernment of whether to divest, the United Church of Christ heard more directly from the Almighty and decided to divest right away - they’re one of the oldest denominations – they’re sort of the ones that date back right to the pilgrims, - and they said it's not OK to be paying our pastors by investing in companies that are running Genesis in reverse.

This is spreading around the world, United Church of Australia, the Episcopal Diocese of Auckland in New Zealand this week, colleges and universities in Europe, and in many parts of the planet, people taking on this industry as forthrightly as they can.

CURWOOD: What’s the logic of divestment?

MCKIBBEN: It’s not that we’re going to bankrupt Exxon. We’re not. But we’re going to politically bankrupt them, morally bankrupt them, make it hard, turn them into the rogue industry they deserve to be. The math is pretty simple. If you go look at all the SEC filings and annual reports and things, the industries that kind of operate like fossil fuel companies have five times as much coal and gas and oil in their reserves as even the most conservative scientists thinks would be safe to burn - five times what it would take to pass a two degree rise in temperature.

But they’re going to burn it. That’s what they’ve told their banks, that’s what they’ve told their investors, they found this coal and gas and oil, they plan to dig it up and sell it, in fact, they look for more every day. Exxon boasts about spending about spending $100 million a year searching for more hydrocarbons even though we have already melted the Artic. In fact, the minute we melted the Artic, their first response was ‘let’s go up there and drill for some more stuff’.

CURWOOD: They don’t burn it though, we burn it.

MCKIBBEN: Well, that’s right, but most of us, day by day, we have some choice about how much we burn, and I trust that everybody who listens to Living on Earth has long since changed their light bulbs and changed their lifestyles to one degree or another. But there are limits to how much one can fully escape the fossil fuel world. You might want to take the train, but if there is no train, it’s hard to do. And the reason that there’s no train is because the fossil fuel industry has made sure that they’ve protected their racket for a long time.

They’re the only industry on the planet, that’s allowed to pour out their waste for free. Nobody else, ever, anywhere, gets to pollute for free - that’s a privilege reserved for these guys. As long as they’re able to hold onto that, the chances of deep structural change that we need are hard to come by.

CURWOOD: So, the subtitle of your book, Oil and Honey, is Education of an Unlikely Activist. What do you think you’ve learned most on this trail?

MCKIBBEN: That’s a good question. I think I’ve learned most, how many people there are who want to do something. The problem with taking action on climate change is it seems too big. The problem is so huge, that there’s nothing that any of us can do as individuals can matter. And in a way, that’s true. I mean, I’ve got all the right light bulbs in my house and solar panels all over the roof, but I try not to confuse myself with the idea that that’s how we’re going to solve this problem.

We’re going to solve it if we come together as a movement, and I think people realize that more and more all the time. If the problem is structural, then the solution has to be a joint solution that changes the balance of power. So, I suppose in some way, that makes us radical, but in other ways, it’s just the opposite. All we’re asking for is a planet that works the way the planet worked for a very long time, for the 10,000 years that is the sum total of human history. Asking for that kind of stability isn’t radical. If anything, it’s conservative.

I think, in the end, radicals work in oil companies. If you’re willing to make your fortune by altering the chemical composition of the atmosphere, if you’re willing to make your fortune by raising the temperature of the Earth, then you’re engaged in the most radical act that any human being’s ever been engaged in, and it’s time for us to check that radicalism.

CURWOOD: Bill McKibben is a writer, distinguished scholar at Middlebury College, and the progenerator of the organization 350.org. His new book is called Oil and Honey: The Education of an Unlikely Activist. Thanks for taking the time today, Bill.

MCKIBBEN: A pleasure as always, friend.

CURWOOD: And there's more of this interview at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Click here for expanded interview with Bill McKibben

- 350.org website

- Get a copy of Oil and Honey here!

- Check out Bill’s website

[MUSIC: Quincy Jones “A Taste Of Honey” from Quincy Jones Plays Hip Hits (Verve Records Reissue 2004)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, James Curwood, Jennifer Marquis and Gabriela Romanow all help to make our show. And this week we're happy to welcome a new intern, Andrew Keys. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org. And like us on our Facebook page, it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER 1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment. Supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by a friend of The Nation, where you can read such environmental writers as Gwen Stevenson, Bill McKibben, Mark Hertsgaard and others at TheNation.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth