Oil and Honey

Air Date: Week of September 20, 2013

A beekeeper at work (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

Bill McKibben is the closest thing the grassroots climate movement has to a leader, organizing opposition to the Keystone XL pipeline and persuading institutions to divest their holdings from fossil fuels. He sits down with host Steve Curwood to discuss his new book, 'Oil and Honey' — an activist memoir and a meditation on beekeeping in Vermont.

Transcript

CURWOOD: In early 2011, the Keystone XL Pipeline Project to bring tar sands crude from Canada to refineries on the US Gulf Coast seemed almost certain to be approved by the State Department, and the White House.

Now that approval's no longer quite such a slam-dunk, and part of what's changed the equation are protests organized by 350.org. In all, more than 1,000 people opposed to the project were arrested on the steps of the White House in the fall of 2011, setting off a fierce national debate on climate change.

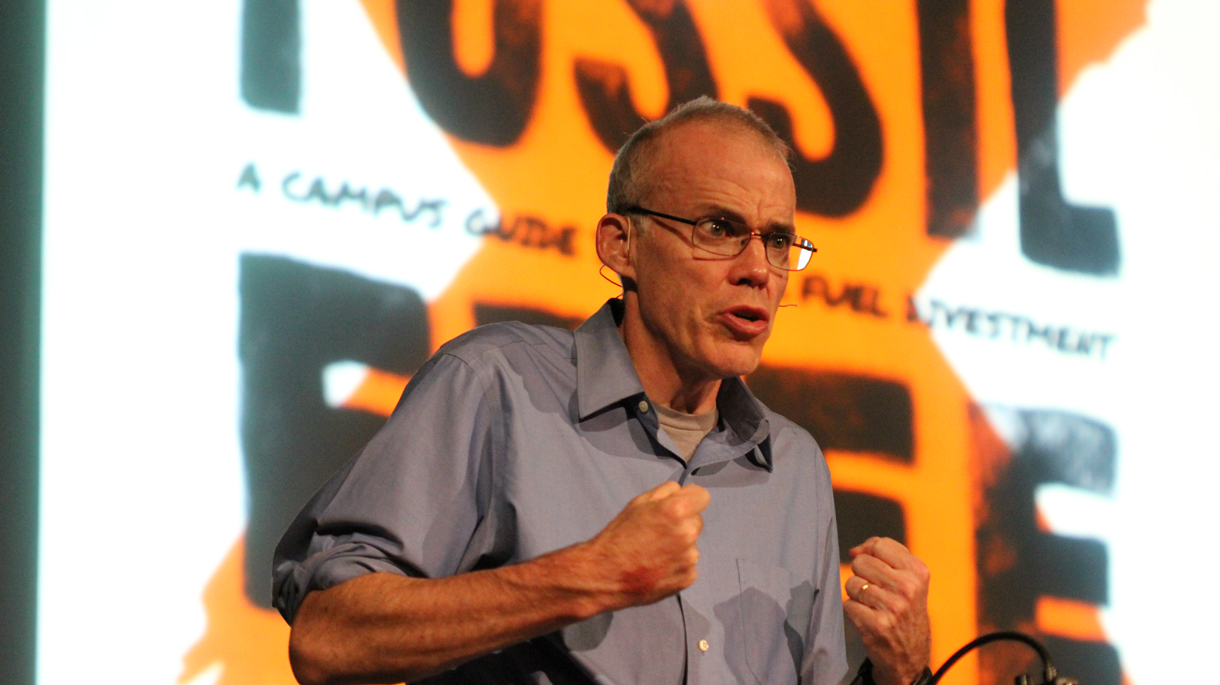

Among those arrested was Bill McKibben, a co-founder of 350.org. His new book, Oil and Honey, is part memoir of the life of a climate activist, and part meditation on beekeeping in Vermont. Bill, welcome back to Living on Earth.

Bill McKibben speaking at a presentation on fossil fuel divestment (photo: Steve Liptay)

MCKIBBEN: Steve, as always it's awfully good to be with you.

CURWOOD: So, Oil and Honey, kind of a bibical reference? What’s this book all about.

MCKIBBEN: Well, I suppose it’s a title that works in a lot of ways. It either calls up those bibical ideas of milk and honey or the idea of oil and water not mixing or whatever, but it’s about the global and the local. Oil stands for the global problem in which we’ve fallen - the greatest problem that humans have ever faced. The honey, and the story about the beekeeper in Vermont, that underlies half of the book, reminds us that it’s possible to imagine a different world, that that world is the one we need to head toward. The reason we have to head off the climate crisis is so we can produce the kind of planet that works for people and works for the rest of creation too.

Oil and Honey by Bill McKibben

CURWOOD: This book is a delight to read, and it’s, well, much more personal that your other books, although you did write about just having one child, having only one. This is really a memoir about your personal transformation from Bill McKibben, the environmental writer to Bill McKibben, the rabble-rousing, getting arrested activist. At what point did you decide that being a commentator about climate issues just wasn’t going to cut it anymore?

MCKIBBEN: You know, I wrote the first book about global warming 25 years ago now, The End of Nature, and at the time, I think I and probably most people thought, “This is an argument about reason and science, and as that science becomes clear to everybody, well then, change will follow, that our leaders will do what’s necessary.” And for year after year, scientists trotted up to Capitol Hill and explained that the worst thing that ever happened is happening, and economists came up behind them and said it’s pretty clear what we need to do; we put a price on carbon to reflect the damage it does in the atmosphere; we’ve internalized the externalities; we won the scientific and economic arguments powerfully; we just weren’t winning any action; we were losing the war.

And at a certain point I think a bunch of us realized, this isn’t about reason. It’s mostly about the incredible power of the fossil fuel industry - they’re the richest industry on Earth. I mean, Exxon made more money the last four years than any company in the history of money, OK? And if we were going to take them on, it wasn’t enough to just win the scientific argument, to write some more books, wasn’t going to substantially contribute to this. We needed to build a movement that could find a different currency than money to work in; the currencies of movement, passion, spirit, creativity. Sometimes we’d need to spend our bodies.

Bees dancing (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: One of the gifts of your book, Bill, is you take us inside this massive demonstration in 2011, really, several days of demonstration action in Washington where you and a number of prominent people get arrested, including Gus Speth, who used to run the Presidential Council on Environmental Quality, a guy with a White House pass gets arrested in front of the White House. Tell us how that all came about.

MCKIBBEN: Well, we’d sent out a letter, Gus - myself and Wendell Berry and some others asking people to come to Washington and get arrested, with the start of this protest over the Keystone Pipeline. And we did not know if anyone would show up, but a lot of people showed up even on the first day of this planned, two-week thing. There were about 100 people there to get arrested. So the police decided they’d try to deter us by treating us somewhat more harshly than they normally do protesters.

The first wave of us got to spend three days in a central cell block in DC, which is about as much fun as it sounds like it would be. But the great pleasure was having Gus in the next cell through the bars, and we could talk. In fact, he shouted out a half hour synopsis of his new book America the Possible to the whole cell block - all the other protestors who were there were - kind of a jailhouse school, you know?

Keystone XL protesters in San Francisco (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

I remember at one point, they weren’t letting us out to see lawyers or anything. Well, Gus Speth’s son was a big heavy duty corporate lawyer in DC, and he’d been papering the jailhouse with writs I think and things, and finally they let Gus out to see his son for a few minutes. And we knew that was our chance to send a message to the press so we tried to think what Gus could say, and he just wrote out this one sentence - you’re right, he had been head of the Council on Environmental Quality, head of the UN Development Program, he’s pretty much as heavy a hitter as there had ever been - and the one sentence he wrote was, “I’ve held a lot of important positions in this town, but none of them seem as important as the one I’m in right now.” Which I thought was a pretty powerful way to explain why movements are really what underwrites all the other environmental policy and investigation and things that we engage in.

CURWOOD: So, three nights in jail, and not just any jail, but DC, downtown, pretty nasty place. I mean, one has to think it’s DC, that the White House would have had some influence over this decision.

MCKIBBEN: Oh, no, no, frankly, I kind of doubt it. I bet they weren’t paying that much attention, at least at the beginning, but they’re paying attention now. Keystone’s become the iconic environmental fight of our time, and sometime this year or next, the President’s going to have to make the call, and when he does, it’ll be an interesting moment. If he does the right thing and blocks it, it’ll be the first time any world leader has ever said ‘no’ to a big project on the grounds that it would be bad for the climate. If he says ‘yes’, I fear that we’ll have no choice but to think of him, at least on this issue, as big talk small action.

CURWOOD: Ah, Bill, you could have easily chosen to write a memoir exclusively about your work with 350.org, but it’s called Oil and Honey, and you spend an awful amount of time writing about your friend whose running an apiary - bee business - down in the Champlain Valley of Vermont. Why was it important to tell us about you and your friend’s relationship with honey?

MCKIBBEN: Well, first of all, this guy is a great character, Kirk Webster; first chemical-free commercial apiarist in the country, his hives thriving, despite the horrible things happening to honeybees ,as you know is happening across this planet, so I wanted to tell his story. But the more that I thought about it, the more it was clear to me, that this was the other half of the story that needed telling.

We need to do two things. We need to make our local places work again, to be able to be more self-reliant, to not depend on supply lines that stretch out forever in the world, but relocalize much of our lives. There’s no way to break the fossil fuel habit without doing some of that, and that’s why it’s beautiful to watch these things happen, and I love to describe the time with the bees and things.

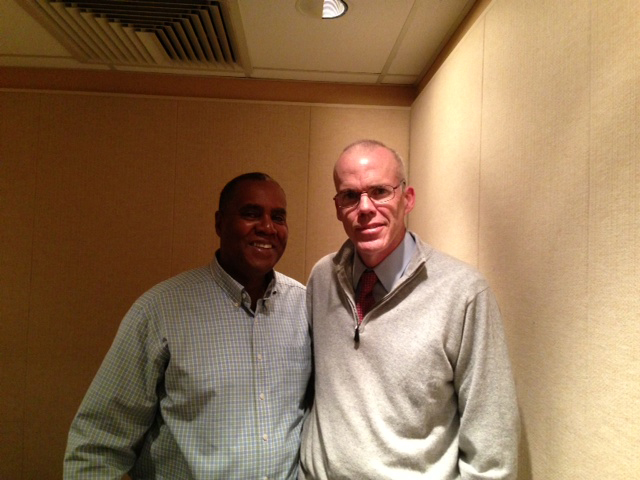

Bill McKibben with host Steve Curwood in the Living on Earth studio. (Emmett FitzGerald)

By the same token, if that’s all we do, then it won’t work. There we were in Vermont in 2011, in beautiful bucolic Vermont, when Hurricane Irene came up the East Coast and passed over record warm waters off New York and New Jersey and soaked up immense amounts of rainfall and shattered every record that we had in Vermont for rain and it just washed away, not just roads and bridges, it washed away a lot of the beautiful organic farms. We’ve got to do both these things - local, global, home and away.

CURWOOD: One of the things you note about bees is their decisionmaking. You say this is a form of consensus.

MCKIBBEN: This fascinating book, about a year old, by a Cornell entomologist named Tom Seal and his question was how do bees...bees swarm in the spring...if they get too many in a hive, half the hive will go and find a new home. You’ve seen them sometime, big colonies of bees hanging from a lightpost or tree. They’re waiting for 48 hours to figure out where their new home will be. It’s not that the queen goes and makes a decision - just the opposite - she’s a bystander.

When that swarm emerges, hundreds of scouts go off in every direction, and they find suitable-sized holes and trees or under eaves and things, and they come back to the swarm and they tell the story. They do it by dancing to sort of describe the place they found and where it is, and the ferocity of the dance indicates how good they think it is. So if they’re really, serious, like Soul Train, then a lot of the bees start paying attention. Some of them go off and look at that hive, and they come back and if they agree, they’ll dance enthusiastically.

There’ll be six or seven contenders at first, and then more and more bees will go stand in one corner, as it were. When you get to about 60 or 70 percent, the whole thing just tips, and everyone agrees, and they fly off together. So it’s a lot like a New England Town Meeting, you know? Very direct democracy. And as far as one can tell, uncontaminated by...I mean, there’s no bees buying off other bees in order to get things to go their way. So yes, a useful reminder of what a more direct form of democracy looks like.

CURWOOD: OK, Bill, when you began 350.org, it seemed you were really focused on the political process, going after politicians to make a change. When did you decide to aim straight at the oil companies?

MCKIBBEN: Well, because we figured out that the politicians were not independent actors in this case. When we’ve watched the Keystone thing, we can predict with unerring accuracy how politicians, how congressmen will vote. If you tell me how much money they took from the fossil fuel industry, I can tell you how they’ll vote on virtually anything related to the energy industry. So we really began to understand that these guys were the problem. And it’s why we’ll play defense with things like Keystone, but why not try to play offense as hard as we can, especially with this divestment campaign that’s burgeoning around the country and very exciting to me.

CURWOOD: Let’s talk about divestment. You’ve been out there, fighting against Keystone, but now you’ve moved into this realm of asking to divest of their investments in fossil fuels.

MCKIBBEN: We focused first of all, on institutions, on colleges, on universities, churches, cities. We started about 10 months ago modeling ourselves really on the work that was done around apartheid in South Africa a generation ago, and it was Desmond Tutu who played such a role in that fight that recorded the seminal video for this. He said if you could see what drought and famine were doing to Africa through no fault of our own, you’d understand why we need you to take up the same tools again.

So far, beginners luck, we’re ahead of the pace of, say, the work on South Africa. 15 or 16 big cities have already divested: Seattle, San Francisco, Portland, Providence, Rhode Island. Six or seven colleges have already done so, most recently San Francisco State. This summer, big religious denominations...Unitarians said they’re going to spent a year in the process of discernment of whether to divest, the United Church of Christ heard more directly from the Almighty and decided to divest right away - they’re one of the oldest denominations – they’re sort of the ones that date back right to the pilgrims, - and they said it's not OK to be paying our pastors by investing in companies that are running Genesis in reverse.

This is spreading around the world, United Church of Australia, the Episcopal Diocese of Auckland in New Zealand this week, colleges and universities in Europe, and in many parts of the planet, people taking on this industry as forthrightly as they can.

CURWOOD: What’s the logic of divestment?

MCKIBBEN: It’s not that we’re going to bankrupt Exxon. We’re not. But we’re going to politically bankrupt them, morally bankrupt them, make it hard, turn them into the rogue industry they deserve to be. The math is pretty simple. If you go look at all the SEC filings and annual reports and things, the industries that kind of operate like fossil fuel companies have five times as much coal and gas and oil in their reserves as even the most conservative scientists thinks would be safe to burn - five times what it would take to pass a two degree rise in temperature.

But they’re going to burn it. That’s what they’ve told their banks, that’s what they’ve told their investors, they found this coal and gas and oil, they plan to dig it up and sell it, in fact, they look for more every day. Exxon boasts about spending about spending $100 million a year searching for more hydrocarbons even though we have already melted the Artic. In fact, the minute we melted the Artic, their first response was ‘let’s go up there and drill for some more stuff’.

CURWOOD: They don’t burn it though, we burn it.

MCKIBBEN: Well, that’s right, but most of us, day by day, we have some choice about how much we burn, and I trust that everybody who listens to Living on Earth has long since changed their light bulbs and changed their lifestyles to one degree or another. But there are limits to how much one can fully escape the fossil fuel world. You might want to take the train, but if there is no train, it’s hard to do. And the reason that there’s no train is because the fossil fuel industry has made sure that they’ve protected their racket for a long time.

They’re the only industry on the planet, that’s allowed to pour out their waste for free. Nobody else, ever, anywhere, gets to pollute for free - that’s a privilege reserved for these guys. As long as they’re able to hold onto that, the chances of deep structural change that we need are hard to come by.

CURWOOD: So, the subtitle of your book, Oil and Honey, is Education of an Unlikely Activist. What do you think you’ve learned most on this trail?

MCKIBBEN: That’s a good question. I think I’ve learned most, how many people there are who want to do something. The problem with taking action on climate change is it seems too big. The problem is so huge, that there’s nothing that any of us can do as individuals can matter. And in a way, that’s true. I mean, I’ve got all the right light bulbs in my house and solar panels all over the roof, but I try not to confuse myself with the idea that that’s how we’re going to solve this problem.

We’re going to solve it if we come together as a movement, and I think people realize that more and more all the time. If the problem is structural, then the solution has to be a joint solution that changes the balance of power. So, I suppose in some way, that makes us radical, but in other ways, it’s just the opposite. All we’re asking for is a planet that works the way the planet worked for a very long time, for the 10,000 years that is the sum total of human history. Asking for that kind of stability isn’t radical. If anything, it’s conservative.

I think, in the end, radicals work in oil companies. If you’re willing to make your fortune by altering the chemical composition of the atmosphere, if you’re willing to make your fortune by raising the temperature of the Earth, then you’re engaged in the most radical act that any human being’s ever been engaged in, and it’s time for us to check that radicalism.

CURWOOD: Bill McKibben is a writer, distinguished scholar at Middlebury College, and the progenerator of the organization 350.org. His new book is called Oil and Honey: The Education of an Unlikely Activist. Thanks for taking the time today, Bill.

MCKIBBEN: A pleasure as always, friend.

CURWOOD: And there's more of this interview at our website, LOE.org.

Links

Click here for expanded interview with Bill McKibben

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth