Endangered Languages

Air Date: Week of July 11, 2014

|

As global biodiversity steadily disappears, so do the world’s languages, says a new study from the World Wildlife Fund finds. Host Steve Curwood speaks with Jonathan Loh, a Research Associate of the Zoological Society of London, about the parallels and the need to conserve both nature and culture.

Transcript

CURWOOD: So if the sea does swallow the island up, it will take with it an English dialect that exists nowhere else. And many of the seven thousand or so languages spoken round the world are also under threat. A new report from the World Wildlife Fund finds that where linguistic diversity declines, biological diversity often falls as well. Jonathan Loh is a Research Associate of the Zoological Society of London and a study co-author, and he says that is why it's important to conserve both biological and cultural diversity. Welcome to Living on Earth, Jonathan.

LOH: Thank you.

CURWOOD: Comparing language, and species diversity seems, well, a bit of an unusual pairing. How did you get into this?

LOH: Well, I am a conservation biologist in my background, and I got interested in the problem of endangered languages. And it really started out as a little bit of a hobby, but the more I looked into it, the more fascinated I became because I realized that, in fact, there’s some extraordinary parallels between biodiversity and linguistic diversity.

CURWOOD: So how did you go about comparing the diversity of language with the diversity of species?

LOH: Biologists use a system called the IUCN red list for assessing the threat status of different species around the world, and we applied exactly the same criteria that a biologist would use to assess the status of a species in order to determine how threatened a language is.

CURWOOD: IUCN, by the way, is the International Union for the Conservation of Nature. So, in sum, what did your study find?

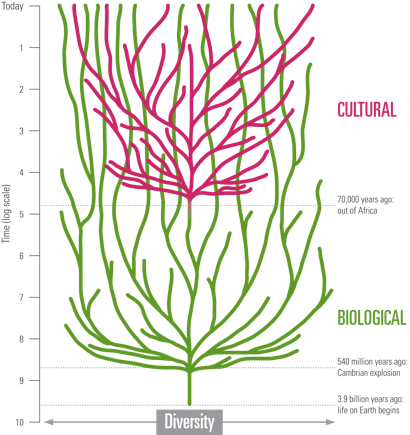

The cultural tree of linguistic diversity began to diversify much later than the biological tree, after humans came on the scene. (Image: Loh and Harmon, 2014. Biocultural Diversity: threatened species, endangered languages. WWF Netherlands. Zeist, The Netherlands.)

The evolution of languages can be traced in much the same way as the evolution of species. (Image: Loh and Harmon, 2014. Biocultural Diversity: threatened species, endangered languages. WWF Netherlands. Zeist, The Netherlands.)

LOH: Overall, we find that the trends in numbers of speakers of different languages around the world on average are declining, and that the rate of decline, globally, is actually very close to the rate of decline in populations of wild vertebrate species.

CURWOOD: So, why is there such a close link between the decline in linguistic diversity and biological diversity?

Baka woman, a speaker of a Niger-Congo language, gathering plants in the forest of La trinationale de la Sangha. Central African Republic (Photo: © Martin Harvey / WWF-Canon)

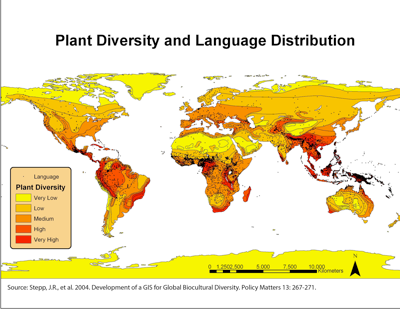

LOH: Some of the drivers that are driving the extinction of biodiversity, and the decline of biodiversity—such as increasing global population, increasing consumption of natural resources, increasing globalization and so on—are applicable to languages as well, and those basic drivers are having a similar effect on linguistic diversity as biodiversity. You can look at the evolution of languages in a similar way to the evolution of species, and languages evolve over time. Of course, languages evolve much faster than a biological species, but nevertheless, you can trace closely related languages back to common ancestors. And then there are also remarkable parallels in the ecology, if you’d like, of languages and if you look at the distribution of the world's languages on a map, you'll see that the patterns of diversity of languages is not evenly spread around the world. There’s a much greater density of languages spoken in the tropics and as you move away from the tropics towards the poles, there are fewer and fewer languages spoken, which is exactly the same pattern that you see with species diversity.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about where you see the parallel declines and the lifestyle of the humans who are losing their languages.

The diversity of languages (black dots) strongly correlates with areas of high plant diversity (darker colors). (Image: Stepp, JR e al. 2004. Development of a GIS for Global Biocultural Diversity. Policy Matters, 13: 267-271.)

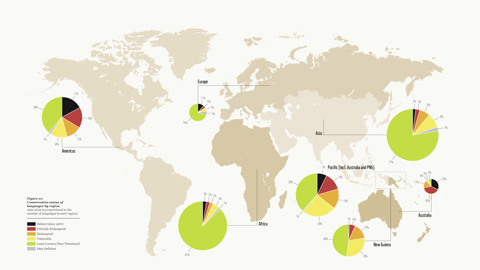

LOH: One of the interesting findings was that where a species goes extinct—because the population of the species declines away to nothing—a language doesn't go extinct because the population of speakers declines away to nothing, but usually because the speakers shift from their mother tongue to a second language, usually a more dominant one, and increasingly this means that the thousands of indigenous languages spoken around the world are being replaced by one of a dozen or so dominant world languages like English, Spanish, Mandarin Chinese. The places which are losing languages most rapidly are the Americas and Australia. About three-quarters of the languages of the Americas are under the threat of extinction, and in Australia, the situation, if anything, is more critical where ninety-five percent of the indigenous aboriginal Australian languages are threatened with extinction and declining extremely rapidly.

CURWOOD: What is your research tell us about the value of these less dominant indigenous cultures?

Australia’s languages are the most severely endangered in the world (92%).

(Image: Loh and Harmon, 2014. Biocultural Diversity: threatened species, endangered languages. WWF Netherlands. Zeist, The Netherlands.)

LOH: The cultures have evolved in a particular environmental context, so they have an extraordinary amount of traditional ecological knowledge—knowledge of the local species, plants, animals, the medicinal uses of them, the migration patterns of animals behavior—this vast wealth of knowledge, and that knowledge is encoded in their indigenous language. And sadly, when children stop learning the language, they also stop acquiring that traditional knowledge. So there’s tens of thousands of years of knowledge acquired over the course of human evolution about different environments of the world, but that's just, kind of, the useful aspects of the traditional culture—because of course the enormous cultural diversity that there is worldwide embodies more than just the knowledge of how to survive. It includes food, music, clothing, everything that we might consider being as part of culture has evolved in different ways, in different parts of the world, and as with species, when a language is lost, it's gone forever. You can never get it back.

CURWOOD: So Jonathan, if both biological and cultural diversity are important to preserve, what should we do, how do we move forward?

Nenets reindeer herdswoman, a speaker of a Uralic language, eating reindeer meat, Kánin Peninsula, Russia, Arctic. (Photo: © Staffan Widstrand / WWF)

LOH: I’ve met now a number of linguists who are working on endangered languages and trying to record them and transcribe them and write down grammars and dictionaries, and it struck me how useful it would be if biologists and linguists could work together on this, for a couple of reasons. There’s this extraordinary wealth of traditional ecological knowledge that's bound up with a lot of the world's indigenous languages, and I think it would be really useful to biologists in understanding how to manage natural ecosystems. And linguists often don’t have the knowledge of natural history that’s necessary in order to be able to record an endangered language because so much of the lexicon is tied up with names of species or types of ecosystems, and linguists don’t have the training in that. And if we can recognize that culture and nature are inextricably interlinked, then working on a biocultural diversity as a whole, as a subject, would be a more fruitful way of looking at conservation.

Jonathan Loh is a Research Associate at the Zoological Society of London and co-author of this study. (Photo: courtesy of Jonathan Loh)

CURWOOD: Jonathan Loh is a Research Associate of the Zoological Society of London. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today, Jonathan.

LOH: It's my pleasure.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth