July 11, 2014

Air Date: July 11, 2014

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Great Lakes Wind Power On Hold

/ Julie GrantView the page for this story

Wind turbines in the Great Lakes could provide a large amount of renewable energy, but stiff opposition and failure to obtain federal grants have put an off-shore wind project in Lake Erie on hold. Julie Grant reports from Ohio. (03:50)

Feds Fund Cape Wind

View the page for this story

The US Department of Energy has given the 130-turbine Cape Wind project a $150 million loan guarantee. Ken Kimmell of the Union of Concerned Scientists tells host Steve Curwood that this federal vote of confidence may help make Cape Wind the first commercial offshore wind turbine farm in the United States (05:47)

Oklahoma Earthquakes Linked to Wastewater Injection

View the page for this story

As part of oil and gas extraction, a large volume of toxic waste water is injected deep underground. This can cause earthquakes, and Oklahoma now experiences more quakes than anywhere in the continental U.S. Cornell University geophysicst Geoffrey Abers tells host Steve Curwood how the research linked waste water injection in Oklahoma to earthquakes 25 miles away. (06:05)

BNSF Railways Workers Forced To Ignore Oil Train Safety

/ Ashley AhearnView the page for this story

One of the largest freight railroad companies in North America, BNSF, transports much of the country’s flammable oil supplies through the Northwest. But BNSF management has forced workers to skip critical safety checks, and fired employees who blow the whistle on unsafe practices. Ashley Ahearn reports from the State of Washington. (08:15)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s trip beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra and host Steve Curwood discuss endangered species news for manatees and wolverines, a fight over water in Texas and some of the many things more likely to kill you than sharks. (03:35)

Tangier, The Shrinking Island in Chesapeake Bay

View the page for this story

As the water rises around Tangier Island in Virginia’s Chesapeake Bay, both the land and the local dialect are disappearing. Kate Kilpatrick, a writer for Al Jazeera America, describes the unique island and its language in conversation with host Steve Curwood. (08:00)

Endangered Languages

View the page for this story

As global biodiversity steadily disappears, so do the world’s languages, says a new study from the World Wildlife Fund finds. Host Steve Curwood speaks with Jonathan Loh, a Research Associate of the Zoological Society of London, about the parallels and the need to conserve both nature and culture. (07:30)

Moose at the Mt. Engadine Wallow

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

Writer Mark Seth Lender watches a moose and her calf as they seek out salt in a briny mud wallow in the foothills of the Canadian Rockies. (03:15)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Ken Kimmell, Geoffrey Abers, Kate Kilpatrick, Jonathan Loh

REPORTERS: Julie Grant, Ashley Ahearn, Peter Dykstra, Mark Seth Lender

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. Millions of gallons of explosive crude oil now ride the rails, and some railway workers are getting fired when they insist on safety checks.

ROOKAIRD: I was just doing my job like I was trained to do that day. I didn't know I was going to be in such a battle.

KROHN: So there's this entire culture of blame and blame the messenger kind of situations. We've had situations where people have been fired because they continually did report safety violations.

CURWOOD: Also, the energy department backs the controversial Cape Wind power project with a multi-million dollar loan guarantee.

KIMMELL: It's a vote of confidence by the federal government in the project. My sense is the federal government is looking at the big picture and seeing that Cape Wind is a critical first-step to a larger development of the offshore wind industry.

CURWOOD: Those stories and wallowing with moose this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies – innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live.

Great Lakes Wind Power On Hold

Offshore wind turbines (Photo: Bigstockphoto)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Offshore wind farms already power more than six million homes in Europe, but so far, no home in America gets energy from commercial offshore wind. It is not for the want of trying. For years there have been efforts to install wind turbines off Cape Cod in the Atlantic. More on that in a moment, but first we go to Ohio. As recently as this spring, a proposed wind farm in Lake Erie near Cleveland looked promising, and then things changed. The Allegheny Front's Julie Grant reports.

LEED has proposed a wind farm off the coast of Cleveland, but has struggled with funding and pushback. (Photo: Bigstockphoto)

GRANT: The idea for building a wind farm in Lake Erie near Cleveland was hatched ten years ago. Wind energy developer Lorry Wagner says leaders started looking toward the energy sector to create more jobs. That’s when they realized the region’s potential for offshore wind energy.

WAGNER: But the real resource is in the lake, and the reason for that is you get about three times the energy over water due to the higher wind speeds and less turbulence than you do on land.

The average American household uses 12,000 kWh every year. A single offshore wind turbine could power over 450 households per year. (Photo: Łukasz Hejnak; Creative Commons Flickr)

GRANT: The Department of Energy estimates the country has an offshore wind capacity of four million megawatts. That’s four-times the generating capacity of all U.S. electric power plants. Wagner is president of the Lake Erie Energy Development Corporation, a nonprofit known as LEED Co. They started developing a pilot project to build a wind farm out in the lake. Other Great Lakes states were also moving forward with offshore wind. In 2012, Pennsylvania, Michigan and others negotiated with federal agencies to streamline the permitting process, and it looked like the Great Lakes might be the nation’s first region to get a project in the water. And LEED Co.’s wind farm was in line to be that project. LEED Co. was in the running for a $47 million dollar grant from the Department of Energy to get things started.

[LAKE ERIE PIER]

Eric Ritter is a spokesperson for LEED Co., the Lake Erie Energy Development Corporation. (Photo: Julie Grant)

GRANT: I met with LEED Co spokesman Eric Ritter in late April on the Cleveland pier. He pointed out into the Lake, at where they planned to build six turbines. Each would be taller than the Statue of Liberty. Ritter was confident LEED Co. would win.

RITTER: We’re anticipating good news in couple of weeks.

GRANT: But they didn’t get good news. Last month, the Department of Energy granted the money to offshore wind projects on the east and west coasts. Cleveland newspapers have called it a gigantic setback for LEED Co., saying it may be time to pull the plug on the project. In fact, the tide seems to have turned on wind development throughout the Great Lakes region. There’s been vocal opposition. Some people are worried turbines might ruin their lake view. Others, like Michael Hutchens of the American Bird Conservancy, say they might harm migratory birds.

Some worry that the turbines will pose a risk to birds such as the American Bald Eagle. (Photo: Bigstockphoto)

HUTCHENS: Because of its location and the importance to bird migration, this is an incredibly important bird migration area, and there are endangered species going through this area as well.

GRANT: Hutchens says more study is needed before turbines are built in the Great Lakes. Instead, it looks like states are retreating. In recent years, an offshore project was abandoned in New York. Pennsylvania has focused on natural gas as an energy source, and in Michigan the legislature introduced a bill to prohibit permits for offshore wind turbines. Some experts look back at the initial purpose of LEED Co’s project, and say the region is potentially giving up on a huge new sector for jobs.

A demonstration wind turbine in downtown Cleveland, Ohio. (Photo: Julie Grant)

KEMPTON: In Europe, there’s a total of fifty-eight thousand workers now working in offshore wind.

GRANT: That’s Willett Kempton. He’s a professor focused on offshore wind at the University of Delaware. Kempton says the Obama administration’s new proposed carbon rules could help make offshore wind more attractive. But he says it hasn’t helped that Ohio just weakened its renewable energy standards, and that the federal government rolled back the wind energy tax credits. Despite the setbacks, LEED Co. isn’t giving up on its wind farm on Lake Erie. A spokesman says they’re disappointed they didn’t get the federal grant money, but they’re still fully committed to making it happen.

CURWOOD: Julie Grant reports for the Allegheny Front.

Related links:

- Bird conservation groups move to block Lake Erie wind turbine project

- Great Lakes wind energy feasibility FAQ

- More from Allegheny Front

Feds Fund Cape Wind

The federal government has promised to back Cape Wind’s 130-turbine offshore wind farm. (Photo: Wessex Archeology; Creative Commons Flickr)

CURWOOD: Well, though Great Lakes offshore wind has yet to see a windfall of federal funding, things are looking better for a development off the coast of Massachusetts that's been controversial for over a decade. The Cape Wind project would build 130 turbines in Nantucket Sound, and generate enough energy to power 200,000 homes. The U.S. Energy Department has now promised to back Cape Wind with $150 million dollar federal loan guarantee, putting it on track to be the first offshore wind farm in the U.S. And Ken Kimmell, President of the Union of Concerned Scientists, says it will be a powerful way to cut global warming emissions.

KIMMELL: It's one of the largest carbon-reducing projects in the world. It would be reducing carbon emissions by about 700,000 tons a year, which to give you a feel for that—that's the equivalent of taking about 150,000 to 175,000 cars off the road every year.

CURWOOD: The U.S. Department of Energy has now promised to back Cape Wind with $150 million dollar federal loan guarantee. That's, of course, not nearly close to the $2.5 billion needed to put the whole project together. How important is that loan guarantee?

KIMMELL: Well, I think it's really going to help. The federal government, of course, has been behind the project and actually issued the permits for it several years ago, but the project is now in the process of finalizing the financing. And what the loan guarantee really does, it's a vote of confidence by the federal government in the project. It’s something that Cape Wind can take to investors and say, look, the federal government has evaluated the risks of this project and is comfortable with that level of risk and so should you be. So I'm hoping and others are as well, that that process of financing can be completed this fall with construction to begin in 2015.

CURWOOD: So if Cape Wind proceeds, it will be the first offshore wind farm in the U.S. Why do you think that Cape Wind got this federal backing while others such as the proposed one in the Great Lakes so far haven’t gotten support?

Ken Kimmell is the President of the Union of Concerned Scientists. (Photo: the Union of Concerned Scientists)

KIMMELL: Well, I mean, I think the Cape Wind project is very far along at this stage. The project now has all of its permits, although there's still a few appeals pending, and it has two signed contracts with Massachusetts utility companies for about three quarters of the output. Those are long-term contracts; they're locked in. They've been approved by the state’s Department of Public Utilities and, you know, right behind Cape Wind is a very exciting development in the northeast, which is the federal government's proposal to lease large tracks of waters further away from shore. And I think the goal here is to get this project up and running, prove that it works, build confidence in the industry as a whole, use the learning from the project to find ways to do it less extensively. My sense is the federal government’s looking at the big picture, and seeing that Cape Wind is a critical first-step to a larger development of the offshore wind industry.

CURWOOD: On the electricity from Cape Wind that’s already been contracted, what are the prices involved? What will the various utilities have to pay compared to present prices?

Cape Wind could supply a majority of the electricity needs for Cape Cod, Martha’s Vineyard, and Nantucket. (Photo: 6SN7; Creative Commons Flickr)

KIMMELL: So the contract prices, and there's no question about this, are higher than market rate. And as natural gas prices have fallen, the gap between the contract price has gone down. There's been an in-depth analysis of what the impacts will be on consumers, and it's about a dollar-fifty a month added to your electric bill. At the time, by the way, when in general electric bills have going down by $20 or $30 dollars a month.

CURWOOD: Now, there were – what? A couple dozen lawsuits filed against Cape Wind over the years. Some of those are still on appeal. How has all that opposition affected things moving forward, do you think?

KIMMELL: Well, I mean, the opposition really has delayed this project for years and years and years. The lawsuits, they do tend to put a shadow over the project and they inhibit investors from financing while they’re pending, but every one of those lawsuits has now been rejected. There may be some additional appeals pending, but not very significant, and so this tactic of delay, while it has worked for a while, is about to come to an end.

CURWOOD: Probably the most visible opponent to Cape Wind was the late Senator Ted Kennedy. Who’s behind the opposition now?

KIMMELL: It's pretty clear that one person who is behind the opposition is Bill Koch, one of the Koch brothers, who’s been very honest about this. He has a large home on Nantucket Sound and he’s said in articles that he doesn't want to have to look at the turbines, and he's funded a group called the Alliance to Protect Nantucket Sound, which has been responsible for these 26 failed lawsuits. And I think it’s well known that the Koch brothers have, you know, investments in oil and gas, and perhaps, given Mr. Koch’s holdings and his financial interest, perhaps he doesn't want to have a viable offshore wind industry competing with fossil fuels.

Some are concerned about the visibility of the turbines against the horizon (Photo: Alan Grinberg; Creative Commons Flickr)

CURWOOD: How optimistic are you now, Ken, that Cape Wind is going to wrap up its funding and stick to this projected timeline—getting done sometime the next couple of years?

KIMMELL: I'm really quite optimistic. I mean, I think the thing that's important is the progress that has been made of late in convincing the American public that climate change is real, and that we've got to start finding clean and renewable sources of energy. And this project clearly would offer that opportunity. The other argument that’s very strong in New England is the recognition that we are over-relying upon natural gas as our source of electricity. We’ve got to have some alternatives in place, and Cape Wind is one of the largest alternatives we have. So, I think that argument is really gaining ground and also giving it, if you will, a bit of a tailwind. And again, if we’re going to meet the carbon reductions that we need to meet, we can’t do it without a strong offshore wind industry. That’s where a lot of renewable energy can come from. We’ve got the technology, and now it’s a question of getting the political will and economics arranged to make it viable. And I think this loan guarantee is a very good sign.

CURWOOD: Ken Kimmell is the former Commissioner of Environmental Protection for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts and now President of the Union of Concerned Scientists. Thanks so much for taking the time today, Ken.

KIMMELL: Thank you for having me.

Related links:

- Read the Department of Energy announcement.

- Read Ken Kimmell’s post about the decision on the Union of Concerned Scientists’ blog.

[MUSIC: Various Artists/Binario “Balinha” from Gilles Peterson’s Brazilika (Far Out Recordings 2009)]

CURWOOD: Coming up: When the price of safety costs workers their jobs. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: This I Dig Of You” from Soul Station (Blue Note Records 1960)]

Oklahoma Earthquakes Linked to Wastewater Injection

Oil drill (Photo: Natalie Maynor; Creative Commons Flickr 2.0)

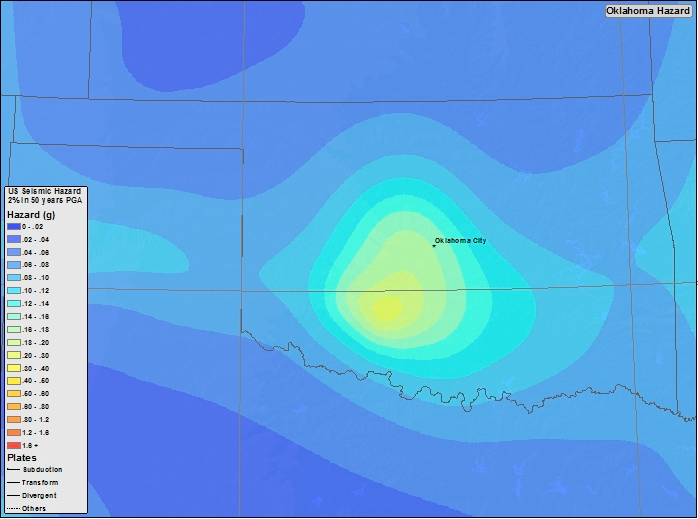

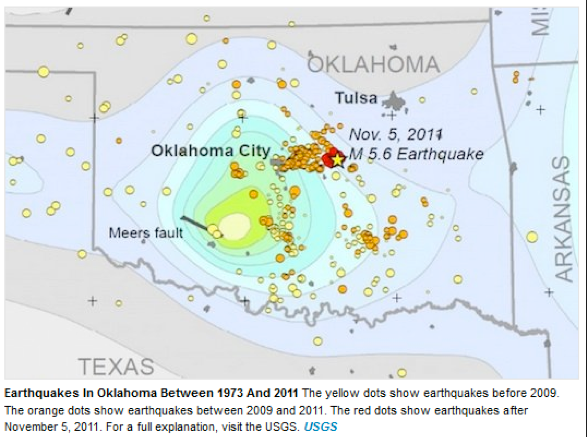

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth; I'm Steve Curwood. Oklahoma has overtaken California as the most earthquake-prone state in the continental U.S. with more than 230 earthquakes measuring 3.0 or more on the Richter scale this year alone. Most of this shaking is due to hundreds of thousands—even millions--of gallons of toxic wastewater from gas and oil drilling being injected underground. Professor Geoffrey Abers of Cornell University was part of a team that recently investigated this and published a paper in Science, and we asked him about it via Skype.

ABERS: Well, our study is actually about earthquakes, so what we think we’ve documented in this paper is a link between the small number of very high-volume injection wells to earthquakes that have been occurring throughout Oklahoma. I think what struck us a couple of years ago has been the really dramatic increase in seismicity across the central and eastern United States, which are usually places that have very few earthquakes. Since 2008, the number of earthquakes in these last seven years has increased at a rate of about five to ten times relative to the preceding several decades across the whole region, and much of that is actually in the state of Oklahoma where the rate of earthquakes increased about forty times relative to the preceding few decades.

Seismic Hazard Map of Oklahoma (Photo: USGS)

CURWOOD: Now I understand that you ran some models. What did you see when you ran those models and simulations?

ABERS: So we used the same kind of modeling tools that hydrologists use to figure out how water moves around in the subsurface. We took what we knew about the wells, which is how much they pump in every month. We took the 89 largest wells in central Oklahoma for the last decade, put this into our model to look at how the pressure is built up inside the formations at depth with time. What we saw was that there’s a large pressure-front that migrated away from Oklahoma City. The rate that it was migrating and the locations of this front match pretty closely the migration of earthquakes that we’ve seen since about 2009, 2010.

CURWOOD: Part of your study focuses on four particular wells. What was so special about them?

ABERS: Well, in the simulations we did, the patterns we saw show that the main pressure changes came out of a group of wells in southeastern Oklahoma City. That’s sort of where the main source of pressure is. So when we did simulations without those wells, we didn’t produce the same kind of patterns at all as we see with the earthquakes.

Locations of earthquakes in Oklahoma between 1973 and 2011 (Photo: USGS)

CURWOOD: How exactly does this wastewater injection affect the creation of earthquakes?

ABERS: Well, we’ve known for a long time that earthquakes are caused by a fault that slips. There’s faults everywhere. While the faults are under some stress, what the water does is it gets into the fault and weakens it, so it can no longer support as much stress as it used to. So it takes a fault that maybe was not ready to have an earthquake anytime soon and suddenly weakens it to the point that it fails and breaks and triggers an earthquake on that.

CURWOOD: How can you tell that all these earthquakes are from wastewater injection and not just, you know, normal seismic activity?

ABERS: So this kind of increase in seismic activity—this is just not just something that we've seen anywhere else in the natural system ever. We see clusters that are big earthquakes that have aftershock sequences and then there’s some swarms in volcanic centers that are fairly localized around a conduit, but to see an increase in earthquakes over such a big area by such an amount is really unprecedented anywhere.

CURWOOD: Now how far away can these earthquakes be felt?

ABERS: So that’s an important thing. What we’ve seen in this study is that earthquakes can be triggered as far away as about 25 miles—this is the furthest sort of cluster that we see associated with this main pressure pulse. It’s much further than people have previously been able to associate with injection wells, where it’s usually been just a couple of miles or less.

CURWOOD: So, what’s likely to happen to seismic activity in Oklahoma if all this wastewater injection isn’t curtailed?

Earthquake damage to a road (Photo: Martin Luff; Creative Commons Flickr 2.0)

ABERS: Well, I mean, it’s hard to know because we don’t have a good idea of where the faults are that are near failure, but if this continues it’s reasonable to expect that earthquakes will continue to happen.

CURWOOD: And are there a lot of earthquakes?

ABERS: Well, we’re seeing so far in 2014, there’s been an average of something more than an earthquake a day at magnitude three or larger.

CURWOOD: How much of a public safety risk is, say, a magnitude 3.0 earthquake?

ABERS: Well, if you knew you were only making magnitude threes, then there’s not that much to worry about. The trouble is, is that there’s nothing in our understanding of how these faults work that gives us a really good feel for how big these earthquakes could be, so the more of these small earthquakes that you’re triggering and you’re making, the higher the risk of there being a larger earthquake as well in the same area.

CURWOOD: What’s the most intense earthquake that’s been documented to have been triggered by wastewater injection?

ABERS: I’d say the 2011 Prague, Oklahoma, sequence. It was a magnitude 5.7; that’s the largest. There were two magnitude 5s that happened within a couple of days of that—that was just outside of our study area.

CURWOOD: Wow, what kind of damage did those earthquakes do?

ABERS: It was a few million dollars in damage to chimneys, roofs, roads, cracks in foundations. It was felt pretty widely around the Midwest as well. It was fortunately in a fairly rural area so the effects certainly could have been worse if it was in a more densely populated part of the world.

CURWOOD: What do you see as the takeaway message from your study?

ABERS: Well, I think the main takeaway is that high volume wastewater injection, or high volume pumping of fluids anywhere, of any kind, is going to increase the probability of triggering earthquakes significantly relative to other kinds of pumping into the subsurface.

CURWOOD: Geoffrey Abers is a Professor of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences at Cornell University. Thanks so much for taking the time with me today.

ABERS: Thanks for having me on the show.

Related links:

- Read the study in Science

- More about Prof. Geoffrey Abers

[MUSIC: Buck Pizzarelli And The West Texas Tumbleweeds “Ain’t Oklahoma Pretty” from Diggin Up Bones (Arbors Records 2009)]

BNSF Railways Workers Forced To Ignore Oil Train Safety

BNSF transports crude oil throughout much of North America (Photo: Roy Luck)

CURWOOD: Fracking has helped boost gas and oil production in the U.S. to the highest in the world, even more than Saudi Arabia. And much of that oil is now shipped by rail, especially from the Bakken shale of North Dakota, the source of highly flammable and explosive crude. More than fifteen trains of Bakken oil cross the Northwest each week, most of it transported by the Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railway. An investigation by the public media collaborative EarthFix reveals some troubling patterns in the way BNSF deals with whistleblowers who voice concerns about safety. EarthFix reporter Ashley Ahearn has the story.

AHEARN: Curtis Rookaird doesn't look like the kind of guy who wants to pick a fight. He's soft spoken yet strong, with a calm, unassuming way about him. He was a conductor for BNSF Railway for six years before he was dismissed in 2010.

ROOKAIRD: I was just doing my job like I was trained to do that day. I didn't know I was going to be in such a battle. And it's a battle for my life, for my family, you know, not just for my job.

The BNSF freight network transports as many as a million gallon of crude oil in a single train. (Photo: Ashley Ahearn)

AHEARN: On February 23rd, 2010 Rookaird went to the rail yard in Blaine, Washington, ready to start lining up train cars and doing safety checks. One of the most important checks is called an air test. That's when a conductor or brakeman walks the length of a train to see if the airbrakes on each car are properly set and functioning.

ROOKAIRD: If you don't have brakes, the cars roll away from you. You don't have control of the train; you can crash into things.

AHEARN: Forty-seven people died last summer when airbrakes on a train carrying Bakken oil from North Dakota were deactivated, allowing it to roll into a community in Quebec. That investigation is ongoing. Testing airbrakes is standard operating procedure for Class 1 railroads, including BNSF. But on that day, Rookaird's supervisor told him and his crew to hurry up and that the airbrake test wasn't necessary.

ROOKAIRD: It was really odd. We were, like, looking at each other going, can he be serious? What is going on here? Why would he even ask that? Yes, it does need to be tested, and he goes, “Well, we'll talk about it later.”

AHEARN: Instead of, “talking about it later,” Rookaird was dismissed. A replacement crew was brought on hours before his shift was supposed to be over. Rookaird called the Federal Railroad Administration, which regulates railroads, and asked if he'd done anything wrong. The FRA said he was right to have conducted the airbrake test, even though his supervisor told him not to. Later, the FRA conducted an investigation of the incident and fined BNSF Railway.

Curtis Rookaird lost his job at BNSF Railway after refusing to skimp on safety procedures. (Photo: Ashley Ahearn)

The FRA declined to be interviewed for this story.

BNSF Railway fired Curtis Rookaird. The company claimed he failed to work efficiently and had not properly filled out his timesheet that day. Rookaird and other current and former BNSF employees say management values speed over safety.

ROOKAIRD: They get performance bonuses based upon velocity and if they don't show those cars moving, they don't get those bonuses.

AHEARN: Curtis Rookaird is not alone in his experience with BNSF Railway. EarthFix found three other pending cases where workers say they were fired for insisting that standard airbrake testing procedures be followed. In more than a dozen interviews, current and former BNSF employees described an intimidating work culture that discouraged workers from reporting accidents, injuries or safety concerns. Several spoke on condition of anonymity because they are afraid BNSF Railway will fire them for speaking out.

BNSF Railway declined to be interviewed for this story.

George Gavalla was the head Safety Officer at the Federal Railroad Administration from 1997 until 2004 and has worked on rail safety issues for 37 years.

Curtis and his wife, Kelly Rookaird, face home foreclosure as their wrongful termination case awaits resolution in court. BNSF was ordered to rehire Mr. Rookaird by OSHA (the US Occupational Safety and Health Administration), but BNSF has appealed the finding. (Photo: Ashley Ahearn)

GAVALLA: If employees are either intimidated or discouraged from fully implementing all the safety rules and procedures it's going to impact on their own safety as well as on the public safety.

AHEARN: For example, say an employee is punished for taking the time to complete an airbrake test, that employee may not insist on conducting that important safety procedure in the future. Railroad safety records have improved over the years, but some in the industry say there is more work to be done.

KROHN: There's this entire culture of blame, and blame the messenger kind of situation. We've had situations were people have been fired because they continually did report safety violations.

AHEARN: That's Herb Krohn. He's a union representative for two thousand rail workers in Washington State.

Railroad worker fatigue is another issue that has dogged federal regulators for years. Railroad engineers and conductors have to be ready to report for duty on relatively short notice and their schedules are often erratic, making it difficult to get adequate or regular sleep. Krohn says that means the people working on any given oil train rolling through Seattle may have been awake for 24 hours at a time, and that, combined with fewer workers per train, could be a recipe for disaster.

KROHN: The history of railroads in America has been one where things generally don't get corrected until people die, and that is frightening to me.

AHEARN: In an emailed statement, BNSF Railway says it conducts frequent operational tests and audits to make sure employees are working safely and in compliance with all company rules. The company also pointed to its formal policies prohibiting retaliation against whistleblowers.

At a rail safety meeting held in Vancouver, Washington in March, BNSF spokeswoman Courtney Wallace told EarthFix the company is committed to worker safety.

WALLACE: We have a safety culture; so if an employee sees something that isn't right—whether that's a supervisor-level or someone below them or at their level—they feel comfortable enough to say, “Stop, that is not the right approach.” And so it doesn't matter, and so it all begins and ends with us.

AHEARN: Curtis Rookaird is skeptical about BNSF Railway's commitment to safety. He believes that he was fired from his job as a conductor because he insisted that standard airbrake tests be done, even though his supervisor said to skip the safety procedure.

The Rookairds live on well-kept cul-de-sac in Snohomish, Washington. Curtis sits at his kitchen table with his wife, Kelly, when their two sons, Reese and Roman, come home from school.

ROOKAIRD: Oh the boys are here.

AHEARN: The couple adopted the boys from Russia not long before Curtis lost his job.

KELLY ROOKAIRD: Hi babe. How was school?

SONS: Good.

KELLY ROOKAIRD: Can I have a kiss?

AHEARN: Roman, who is nine, plops down next to his mom.

KELLY ROOKAIRD: Prior to the BNSF incident our world was pretty perfect. We were very very happy. We finally got our kids and it was a miracle that we got them. We were very blessed.

ROMAN: And the lord blessed us all.

KELLY: Blessed you too, right?

[LAUGHS]

AHEARN: Curtis Rookaird has been in a legal battle with BNSF Railway for more than four years now, and things for his family have started to fall apart. He left for a while to work in the oil fields of North Dakota as a truck driver, but the pay wasn't as good as it was when he worked for BNSF. The family is now more than a hundred thousand dollars behind on their mortgage payments.

There's a fire in Kelly Rookaird's eyes when she talks about the ongoing case. She says that BNSF Railway, which is controlled by billionaire Warren Buffett, is delaying justice and had no right to fire her husband.

KELLY ROOKAIRD: Safety should come over money, and that's what I'd like to say to Warren Buffet. Wake up. Us little people—you can take everything from us—but you're not going to take our pride and our dignity. He loved his job [CRYING] and we loved his job too. And he would take those boys out to the train and teach 'em about the engines, and let everybody see his kids. He thought, well, maybe one day one of these kids might want to follow in his footsteps, but now that we go through this, I don't know. It's bittersweet, you know.

AHEARN: In September of last year, the Federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration ruled in favor of Curtis Rookaird and ordered BNSF Railway to put him back to work. BNSF Railway appealed OSHA's ruling, as they have done with several other similar whistleblower cases.

The Rookaird's home is now in foreclosure, and the family could be forced to move within a month. Curtis Rookaird's case won't go before a federal court until May of next year.

I'm Ashley Ahearn in Snohomish Washington.

CURWOOD: Tony Schick from EarthFix helped report this story. There's more at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Read the piece on EarthFix, with documents

- A map of crude oil transport facilities from BNSF

- More about explosive oil trains

[MUSIC: Michael Bloomfield & Al Kooper “Albert’s Shuffle” from From His Head To His Heart To His Hands (Columbia Legacy Records 2014)]

Beyond the Headlines

Wildlife Biologists at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service are recommending that the wolverines in the lower 48 states be classified as threatened, but their finding has been rejected by Regional USF&WS director Noreen Walsh. (Photo: Birgit Fostervold; Creative Commons Flickr 2.0)

CURWOOD: Off to Conyers, Georgia, now to check in with Peter Dykstra, the publisher of Daily Climate.org and Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org. So Peter, what are you finding beyond the headlines this time?

DYKSTRA: Well, hi, Steve. We've got some news about a famously gentle species, and a famously ferocious one. We’ll start with manatees—those big, flabby sea cows that could be found in lagoons in Florida may soon lose their status as an endangered species. Manatees were hammered by boat collisions, and pollution, and habitat loss throughout the twentieth century, but now the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service says that it “may be warranted” to lift that endangered status as manatees recover. The government responded to a petition from a conservative group, called the Pacific Legal Foundation, but most Florida conservationists say that it’s way too soon to lose protections for manatees.

CURWOOD: And what’s the ferocious species you mentioned?

DYKSTRA: Wolverines. Government biologists recommended that the last three-hundred wolverines living in the lower forty-eight states need a listing as a threatened species, but their bosses at Fish and Wildlife Service said don’t go there. The wolverine population is believed to be growing slightly, but the scientists say that climate change could hamper the cold winters that wolverines thrive in.

CURWOOD: So it sounds like two potential setbacks for struggling species. What else do you have for us?

DYKSTRA: Well, we always hear that drought impacts farmers and wildlife, but how about the impacts on industry? The Texas Tribune just reported on a brewing water war on the drought-stricken Brazos River. Dow Chemical operates a chemical complex near the mouth of the river. It’s undergoing a multi-billion dollar expansion, and Dow actually has a legal claim to use a huge amount of water from the Brazos River. That pits the company against all of the farmers, ranchers, and the growing cities upstream along the 900-mile long river.

CURWOOD: And as Mark Twain supposedly put it, ‘whiskey’s for drinkin’ and water’s for fightin’ over’.

DYKSTRA: Exactly, and if the Texas drought persists, the fight is going to be sooner and uglier than we thought.

CURWOOD: Hey, what did you bring us from the environmental calendar this week?

DYKSTRA: It’s from ninety-eight years ago, this week. This was 60 years before the movie “Jaws” came out, a great white shark killed four people and maimed a fifth person along the Jersey shore. And that, of course, caused a frenzy, as you might expect, and really gave birth to the contemporary image of sharks as cold-blooded psycho killers.

CURWOOD: Well, they are mostly cold-blooded, but, hey, don’t humans kill far more sharks than they kill us?

DYKSTRA: They do. Sharks get us one at a time; they get us only a few times a year. Humans take sharks by the tens of millions each year. They take them by accident. They take them on purpose for shark fin soup, which is now very trendy with the growing middle class in China. But for all the Jaws-hype and Shark Week-hype, here are a few things that are more deadly to people than sharks are. The first one: vending machines.

CURWOOD: Did you just say vending machines?

People die trying to get items stuck in vending machines twice as often than those attacked by sharks, according to the Consumer Product Safety Commission. (Photo: Midorisyu; Creative Commons Flickr 2.0)

DYKSTRA: I did indeed. A few years back, the Consumer Product Safety Commission tallied up the number of Americans who died because they rocked a vending machine to try and get their change out or dislodge their bag of Doritos. It’s about twice as frequent a cause of death as shark attacks. Want to hear a few more causes of death that are bigger than sharks?

CURWOOD: Well, there’s no point in stopping you now.

DYKSTRA: OK. Deer. They seem so adorable, but car and deer collisions are far more deadly than shark attacks. A few more things: boating accidents kill way more people. Hunters shooting other hunters kill more people than sharks do. And here’s my favorite, when you dig a huge sand hole at the beach and sometimes it caves in and smothers the person who dug it, that kills more people than sharks do.

CURWOOD: OK. So let’s all be careful out there. You can find links to all these stories, and causes of death, at LOE.org.

CURWOOD: Thanks so much, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Thank you, Steve. We’ll talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra is the publisher of Environmental Health News. That’s EHN.org and the DailyClimate.org.

Related links:

- Manatees may be soon only be considered “threatened”

- More about the fight over water in Texas

- The New York Times story from 1916 about a series of shark attacks

[MUSIC: Lee Morgan “Davisamba” from The Rajah (Blue Note Records Reissue 2014)]

CURWOOD: Coming up: How disappearing languages and species are linked. That's ahead here on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems provides building technologies and supplies, container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food, and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Hank Mobley: “A Caddy For Daddy” from A Caddy For Daddy (Blue Note Records 1965)]

Tangier, The Shrinking Island in Chesapeake Bay

Freddie Wheatley takes a break from painting maroon buoys for his crab pots to greet a friend. (Photo: Ian C. Bates)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. With their vulnerability to rising seas, low-lying small island nations in the South Pacific are considered ground zero for global warming. But an island in America is also under an immediate threat as well. Little known Tangier Island in Chesapeake Bay, a dozen miles off the coast of Virginia, is home to people with a unique way of speaking. Kate Kilpatrick, a writer with Al Jazeera, America has written about the island which may soon be underwater as well. Welcome to Living on Earth, Kate.

KILPATRICK: Hi, thank you.

CURWOOD: So first tell us a bit about Tangier Island. What’s it like there?

Richard Laird is one of the watermen of Tangier, many of whom feel the crab sanctuary puts them at an unfair disadvantage. As the northernmost fishing community affected by the sanctuary and its rules, they argue they have less time to catch crabs. (Photo: Ian C. Bates)

KILPATRICK: Tangier Island—it’s a fairly isolated island. There's no bridge or tunnels to get there, so if you want to get to the island you have to take one of the daily ferries or the mailboat that delivers everybody’s mail. There’s no mall, no movie theaters; there’s no arcades. There's a couple of restaurants that are open during the busy season in summer, but when we were there at the end of March, there's just one restaurant open with really odd hours. What was really interesting for me reporting there, what was unusual, was how easy it was to talk to people and it’s actually the greatest place to report because it's so small. There's a road that just goes in a circle on the island. And I would literally just start walking down that road and pretty much bump into people that I needed to talk to, and if I needed to interview the mayor, I went to his door and knocked on his front door. He wasn't there, so I went to see where his boat was, whether he was at his crab shack or not. So it’s not like other places where you have to schedule meetings, you just kind of bump into people, and if you don’t find them, you ask their neighbor where they are, and they’ll tell you.

Tangier Island relies on crabbing and fishing—but young people are moving away rather than becoming watermen. (Photo: J. Albert Bowden II)

CURWOOD: Now, this island’s only a few miles off the coast of Virginia, but many of the people to speak her own dialect of English. What's it like?

KILPATRICK: They do, and that was part of the reason why I was interested in the story. I’d listened to some of the videos on YouTube, and it’s just, sort of, this strange accent that I hadn’t heard before, and a lot of people call it Elizabethan or Restoration era English accent. And it’s not really that. I mean, I’m not a linguist, but a lot of my research came from a book written by a local Tangierman, David Shores. And he basically says that it’s dialects that comes from the early settlers that came from the Cornwall era of southwest England, and because of the isolation of the island, a lot of that dialect has just stuck around. And so, while the younger generation—you know, everyone has satellite TV, everyone has iPads—so it’s beginning to become a little bit more like standard English among the younger people, but when you get to talking to some the older folks, especially the older watermen, you’ll really hear it.

Storms and floods jostle old graves on Tangier Island. (Photo: baldeaglebluff; Creative Commons Flickr)

CURWOOD: You recorded some people talking for your story. Let’s listen to a clip you put together of the strange phenomenon islanders call “backwards talk.”

MAN: If I wanted to tell you that you had missed the opportune time to do something, I would not say that. I would say, ”Well, you’re too soon,” meaning you’re late.

WOMAN: Like when my boys will come in from being out, playing or whatever all day, I’ll tell them to go take their shower, and they’re like, “No, mom, we don’t need them.” I’ll say, “Wait, I bet you’re sweet,” which means smelly, not that they’re sweet. They’re smelly.

Due to rising waters, newer graves are located in residential areas—even in people’s yards. (Photo: baldeaglebluff; Creative Commons Flickr)

MAN: If, just for instance, a boat goes by or something, “Oh, she don’t go, she don’t get out—she don’t go very fast.” Stuff like that, but what we’re really saying how fast she goes.

MAN2: Nice looking lady comes down the street, and one guy will say to the other one, “Man, was that an ugly girl?” which means, she was a nice looking girl.

WOMAN: Just say, like our TV broke or something like that—an appliance broke and we had to get a new one. We’re just like, “Well, that’s going to be cheap,” which means it’s going to cost a lot of money. So it would be hard to catch on to everything if you tried to live here, you know. It’d take you a little while.

During storms and high winds, some homes on Tangier Island flood. (Photo: baldeaglebluff; Creative Commons Flickr)

KILPATRICK: A lot of their backwards talk just seems like an extreme form of sarcasm, but then they have some other expressions like, “Got the mibs”. Got the mibs, means you’re smelly or you stink. Or if you’re thirsty, you’ll say, “as dry as Peckerd’s cow”, and Peckerd apparently was a farmer that used to live on Tangier many years ago.

CURWOOD: So when did folks come the southwest of England to Tangier Island?

KILPATRICK: Yeah, we’re talking early 1600s, so I think it was 1608, that is when Captain John Smith supposedly discovered Tangier. And then sort of the turn for the island was the War of 1812—the Royal Marines built Fort Albion, which is no longer there; it’s now completely underwater. But they were offering American slaves to come there and they would be free. And they enlisted them in the Royal Marines, and then a lot of them ended up relocating to British Colonies in the Caribbean. So a lot of residents on the island are really proud of that, that thousands of slaves took their first steps of freedom on Tangier Island.

Crab traps and fishing gear are a common sight on Tangier Island. (Photo: schweizup; Creative Commons Flickr)

CURWOOD: So what’s the economy like on this island?

KILPATRICK: The economy’s rough. It’s especially rough for younger people, but basically the breadwinners of the family are the watermen, and they spend their days oystering in winter and crabbing in summer. They work six days a week; Sundays are off. But the population is shrinking. It's shrinking and it's aging. At Tangier’s height there was twelve hundred people on the island. By 2000, there was half that number—it dropped to six hundred—and now there’s right around 470 people on the island. So young people, there really aren't any sort of jobs or economic opportunities on the island. There isn’t a college on the island, so young people typically, either head to the mainland to go to college or to get jobs working on the tugboats.

CURWOOD: Let's take a listen now to a waterman, Gary Parks, talking about the population decline.

A waterman watches a blue heron. (Photo: Chesapeake Bay Program)

PARKS: When we grew up, that's all we wanted to be was a waterman. All our children are moving off to other careers ’cause there’s just no more future in the water business. On the mainland, they can get jobs, you know. They’re on the mainland; they can drive to their work. But here on Tangier, on the island, well, it’s all we’ve got, is the water. If you’re not a waterman, you can’t make it on Tangier.

CURWOOD: Now how is sea level rise affecting the island and the crabbing economy?

KILPATRICK: So, the sea level rise is really more affecting land on the island itself, and some people on the island actually dispute it. They say it’s not an issue of the sea level rising; it’s actually just the land sinking. And they’ll point to different markers that show that the water’s lower than it was in previous years. But the fact is, that even the highest parts of the island are only three, three and a half feet above water; so when there’s rain, you’ll see front yards are just a huge pool of water. And the water’s constantly coming up, even when there's not a storm.

CURWOOD: So, the island, I gather, is being eroded away slowly. What are the projections for erosion in the years to come?

Kate Kilpatrick. (Photo: Kate Kilpatrick)

KILPATRICK: Well, right now, the western side of the island is kind of getting bad, or the worst, and they're losing fifteen to sixteen feet a year. The uppers is sort of the area that's most threatened at the moment. It had been the center of the town, and then around the 1920s people started leaving that area because of the encroaching water, and just because the center of town was moving south, and so that area now is completely abandoned and uninhabited. And it's believed it'll be totally underwater by 2100. They're trying to get a seawall. In 2016 they’re going to finish building a seawall that'll protect the harbor which is where the mailboats and the ferries come in. But residents are worried that if the storm comes before that it could wipe them out before they even get the seawall.

CURWOOD: That's Kate Kilpatrick, who reported on the threats facing Tangier Island in Al-Jazeera America.

Related links:

- See Kate Kilpatrick’s piece, “Treasured Island,” on Al Jazeera America

- Read the Washington Post’s article on Tangier Island’s Jetty

- When hurricane Sandy hit, it exhumed old graves on the island. Here’s the local news coverage

Endangered Languages

Ashaninka woman, a speaker of an Arawakan language. Nueva Victoria, Yurua River, Ucayali Province, Peru. (Photo: © James Frankham / WWF-Canon)

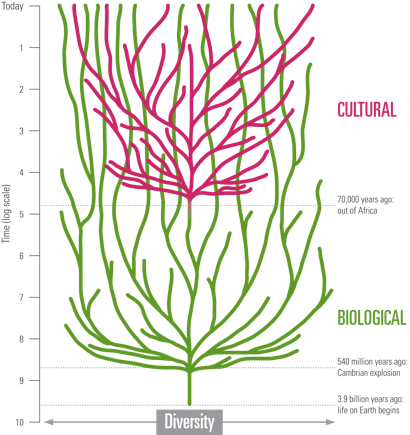

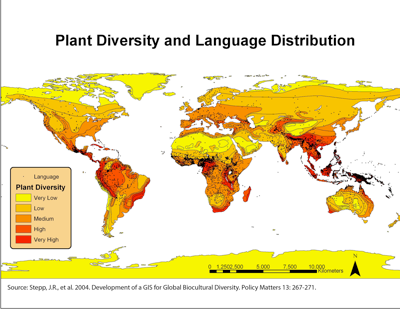

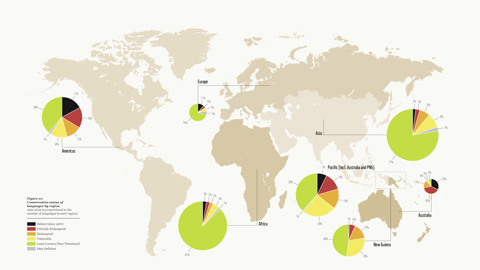

CURWOOD: So if the sea does swallow the island up, it will take with it an English dialect that exists nowhere else. And many of the seven thousand or so languages spoken round the world are also under threat. A new report from the World Wildlife Fund finds that where linguistic diversity declines, biological diversity often falls as well. Jonathan Loh is a Research Associate of the Zoological Society of London and a study co-author, and he says that is why it's important to conserve both biological and cultural diversity. Welcome to Living on Earth, Jonathan.

LOH: Thank you.

CURWOOD: Comparing language, and species diversity seems, well, a bit of an unusual pairing. How did you get into this?

LOH: Well, I am a conservation biologist in my background, and I got interested in the problem of endangered languages. And it really started out as a little bit of a hobby, but the more I looked into it, the more fascinated I became because I realized that, in fact, there’s some extraordinary parallels between biodiversity and linguistic diversity.

CURWOOD: So how did you go about comparing the diversity of language with the diversity of species?

LOH: Biologists use a system called the IUCN red list for assessing the threat status of different species around the world, and we applied exactly the same criteria that a biologist would use to assess the status of a species in order to determine how threatened a language is.

CURWOOD: IUCN, by the way, is the International Union for the Conservation of Nature. So, in sum, what did your study find?

The cultural tree of linguistic diversity began to diversify much later than the biological tree, after humans came on the scene. (Image: Loh and Harmon, 2014. Biocultural Diversity: threatened species, endangered languages. WWF Netherlands. Zeist, The Netherlands.)

The evolution of languages can be traced in much the same way as the evolution of species. (Image: Loh and Harmon, 2014. Biocultural Diversity: threatened species, endangered languages. WWF Netherlands. Zeist, The Netherlands.)

LOH: Overall, we find that the trends in numbers of speakers of different languages around the world on average are declining, and that the rate of decline, globally, is actually very close to the rate of decline in populations of wild vertebrate species.

CURWOOD: So, why is there such a close link between the decline in linguistic diversity and biological diversity?

Baka woman, a speaker of a Niger-Congo language, gathering plants in the forest of La trinationale de la Sangha. Central African Republic (Photo: © Martin Harvey / WWF-Canon)

LOH: Some of the drivers that are driving the extinction of biodiversity, and the decline of biodiversity—such as increasing global population, increasing consumption of natural resources, increasing globalization and so on—are applicable to languages as well, and those basic drivers are having a similar effect on linguistic diversity as biodiversity. You can look at the evolution of languages in a similar way to the evolution of species, and languages evolve over time. Of course, languages evolve much faster than a biological species, but nevertheless, you can trace closely related languages back to common ancestors. And then there are also remarkable parallels in the ecology, if you’d like, of languages and if you look at the distribution of the world's languages on a map, you'll see that the patterns of diversity of languages is not evenly spread around the world. There’s a much greater density of languages spoken in the tropics and as you move away from the tropics towards the poles, there are fewer and fewer languages spoken, which is exactly the same pattern that you see with species diversity.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about where you see the parallel declines and the lifestyle of the humans who are losing their languages.

The diversity of languages (black dots) strongly correlates with areas of high plant diversity (darker colors). (Image: Stepp, JR e al. 2004. Development of a GIS for Global Biocultural Diversity. Policy Matters, 13: 267-271.)

LOH: One of the interesting findings was that where a species goes extinct—because the population of the species declines away to nothing—a language doesn't go extinct because the population of speakers declines away to nothing, but usually because the speakers shift from their mother tongue to a second language, usually a more dominant one, and increasingly this means that the thousands of indigenous languages spoken around the world are being replaced by one of a dozen or so dominant world languages like English, Spanish, Mandarin Chinese. The places which are losing languages most rapidly are the Americas and Australia. About three-quarters of the languages of the Americas are under the threat of extinction, and in Australia, the situation, if anything, is more critical where ninety-five percent of the indigenous aboriginal Australian languages are threatened with extinction and declining extremely rapidly.

CURWOOD: What is your research tell us about the value of these less dominant indigenous cultures?

Australia’s languages are the most severely endangered in the world (92%).

(Image: Loh and Harmon, 2014. Biocultural Diversity: threatened species, endangered languages. WWF Netherlands. Zeist, The Netherlands.)

LOH: The cultures have evolved in a particular environmental context, so they have an extraordinary amount of traditional ecological knowledge—knowledge of the local species, plants, animals, the medicinal uses of them, the migration patterns of animals behavior—this vast wealth of knowledge, and that knowledge is encoded in their indigenous language. And sadly, when children stop learning the language, they also stop acquiring that traditional knowledge. So there’s tens of thousands of years of knowledge acquired over the course of human evolution about different environments of the world, but that's just, kind of, the useful aspects of the traditional culture—because of course the enormous cultural diversity that there is worldwide embodies more than just the knowledge of how to survive. It includes food, music, clothing, everything that we might consider being as part of culture has evolved in different ways, in different parts of the world, and as with species, when a language is lost, it's gone forever. You can never get it back.

CURWOOD: So Jonathan, if both biological and cultural diversity are important to preserve, what should we do, how do we move forward?

Nenets reindeer herdswoman, a speaker of a Uralic language, eating reindeer meat, Kánin Peninsula, Russia, Arctic. (Photo: © Staffan Widstrand / WWF)

LOH: I’ve met now a number of linguists who are working on endangered languages and trying to record them and transcribe them and write down grammars and dictionaries, and it struck me how useful it would be if biologists and linguists could work together on this, for a couple of reasons. There’s this extraordinary wealth of traditional ecological knowledge that's bound up with a lot of the world's indigenous languages, and I think it would be really useful to biologists in understanding how to manage natural ecosystems. And linguists often don’t have the knowledge of natural history that’s necessary in order to be able to record an endangered language because so much of the lexicon is tied up with names of species or types of ecosystems, and linguists don’t have the training in that. And if we can recognize that culture and nature are inextricably interlinked, then working on a biocultural diversity as a whole, as a subject, would be a more fruitful way of looking at conservation.

Jonathan Loh is a Research Associate at the Zoological Society of London and co-author of this study. (Photo: courtesy of Jonathan Loh)

CURWOOD: Jonathan Loh is a Research Associate of the Zoological Society of London. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today, Jonathan.

LOH: It's my pleasure.

Related link:

Read the World Wildlife Fund report

[MUSIC: Laurie Anderson “Speak My Language” from Talk Normal (Warner Bros 2000)]

Moose at the Mt. Engadine Wallow

Mother moose and her calf wallow in briny muck. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: Head fifty miles west from Calgary in Alberta, and you'll reach the edge of the Canadian Rockies with its jagged snow-capped peaks. Writer Mark Seth Lender visited Mount Engadine Lodge there. But it wasn't the spectacular mountains that riveted his gaze at sunrise; instead, he was captivated by the mud wallow just below the lodge.

Moose at the Mt. Engadine Wallow

© 2014 Mark Seth Lender

All Rights Reserved

LENDER: The land lies between two rows of mountains, white-capped like a sea of stone. Down in the trough between them water flows, not an ocean, but only the trickle of a stream: small reminder of the torrent that once flowed in a distant time…a time of ice.

In the foothills of the Canadian Rockies, a moose and her calf search for dietary salts, sodium and magnesium, necessary for life. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

The glacier’s grinding advance. All that rock and dust—the fines and filings of the land—made this soft silt ground, and the water that remains combines to make a mire, this La Brea made of mud where moose come to wallow in the dark and tar-like stuff. They are mothers and daughters and mothers and sons. They sink, up to their bellies and their hips, into the sucking bog, fossils in the making.

Instead, their long legs pull free. They turn. They bow their heads to drink.

A moose and her calf drink salty water that fills their footprints. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

Each hoof prints a cup that fills with water, and in that water are valuable things more pressing than thirst. Their quest is not for wet, but salt, the salt of the earth that once was mountains: calcium, magnesium in oxides and carbonates, sodium and chloride. Without these buffering salts they will starve though their bellies bulge with the sweetest grass on earth. Without salt, the ferment of digestion stops. And the moose knows this and shows the way to her calf-of-the-year.

And the calf, new in this world, watches and stands as close as she can—moving side to side; standing flank to flank; head to head; back to back.

A calf mirrors her mother, learning that they cannot survive on grasses alone. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

The calf and her mother, like atoms bound in a carbon ring, each mirroring the other. By salt they grow, healthy and fat.

The wide stiff brush of hair that runs along the calf’s young spine is a throwback to Lascaux and Chauvet where our ancestors drew hers in ochre and umber, and charcoal mixed with fat in those intimate torch-lit spaces in the ground. Portraying with the first paint in human hands what life was for all of us, on the edge of a vast and frozen place—its trepidation, borne like the whims of season without complaint, its hope, like sun entering the dark mouth of the cave; its agonies, at the end of the game.

Thirty thousand years ago that was. Is there much difference, now?

CURWOOD: To see what Mark Seth Lender saw, slog on over to LOE.org.

Related links:

- Mt. Engadine Lodge

- About Alberta, Canada

- Read more of Mark Seth Lender’s work on our site

- Follow Mark Seth Lender’s work on his page

[MUSIC: Monty Alexander “Do The Kool Step” from Monty Meets Sly And Robbie (Telarc Jazz 2000)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, James Curwood, Lauren Hinkel, Jake Lucas, Abi Nighthill, Jennifer Marquis and Olivia Powers all help to make our show. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org, and like us on our Facebook page; it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more. www dot stonyfield dot com.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth