Losing Ground in Louisiana

Air Date: Week of September 19, 2014

The network of canals cut through the marshes to enable oil and gas extraction has driven Louisiana’s coastal land loss. (Photo: John McQuaid; Flickr CC2.0)

Levees along the Mississippi river and years of oil and gas extraction have caused dramatic erosion and subsidence in Louisiana. Bob Marshall, a reporter with the New Orleans news-site The Lens, discusses the new interactive project he developed with ProPublica with host Steve Curwood and explains how the vanishing land could displace thousands of people if nothing changes.

Transcript

CURWOOD: Louisiana is growing smaller and smaller, thanks to changes in the Mississippi delta that were designed to increase flood protection and enhance oil and gas production. Bob Marshall has been covering coastal land loss in Louisiana for decades. He’s now a writer with the Lens, a non-profit news site in New Orleans. He recently collaborated with ProPublica to put out a graphically enhanced report called Losing Ground. Complete with dynamic maps and images, Losing Ground shows just how much of Louisiana’s wetlands have been eaten up by the Gulf of Mexico. Bob Marshall joins us now. Welcome to Living on Earth.

MARSHALL: My pleasure to be here.

CURWOOD: So the project is called "Losing Ground". How significant is this land loss crisis? How quickly are we Losing Ground down in Louisiana?

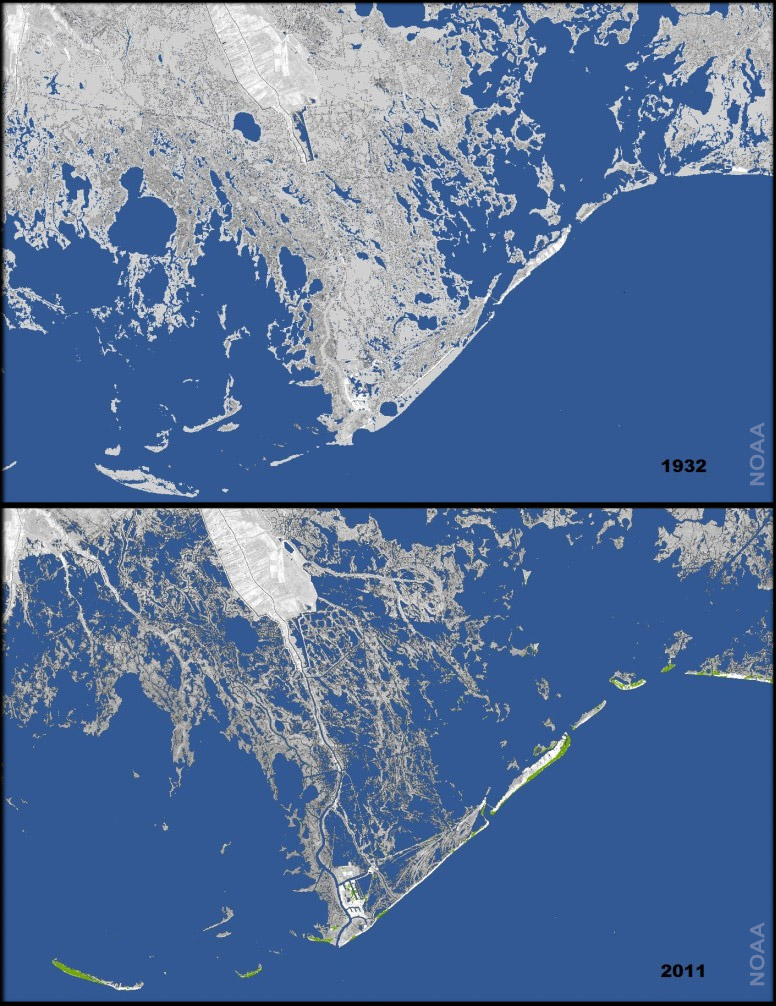

Image showing land loss since 1932 (Photo: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; public domain)

MARSHALL: Well, right now they're losing it at about 16 square miles a year. They like to say a football field every 48 minutes, but if you go back 20 or 30 years ago we were losing as much as 50 square miles a year. So we've lost about 2,000 square miles since the mid-1930s, and there's very little left now in southeast Louisiana.

CURWOOD: Now, I gather a lot of this has to do with the way people have controlled the Mississippi River over the years. Describe that process for me.

MARSHALL: Well, this whole area of the state, all of south Louisiana, really, from Mississippi to Texas, was built by the Mississippi River. It's delta-building process going back about 7,000 years when the end of the last glacier period. You know, when the river hits this flat plain, it slows down and all the sediment it's carrying begins to fall out. And it wasn't just the main stem of the river, it was all these distributaries that peeled off the river on its delta plain. So there was this big, really spider web of distributaries carrying all this freshwater and sediment, and during the spring floods, the river would come over its banks, and over the distributaries banks and spread this—really, nature's cement, if you want to call that—out all across this area. And so that process was still going on when Europeans arrived, and when New Orleans was founded in 1718, they were still building land out in the Gulf of Mexico. And everything went along as nature intended it until we began developing along the river, and people began putting up levies so that they wouldn't get flooded by this river every spring.

Many of the people living in wetland communities have already been forced to migrate because of land loss. (Photo: Alicia Lee; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So what did the levees do to the river exactly? Why did it make it lose land?

MARSHALL: Well, the levees block the river from spreading more settlement out on its delta, and so when a river can't get back out to replenish its delta, that delta begins subsiding. So there were levies on the Mississippi really going back to the 1850s, but after the Great Flood of 1927 when most of the Mississippi River Valley from Illinois to Louisiana was flooded, Congress said, "Never let this happen again." And so the Corps built these great levies, and they put the river in a straitjacket permanently blocking the river from getting back to its delta to replenishing this land. If that's all we had done, the researchers say that the delta would have been subsiding at an infinitesimal rate, milliliters per year, and the wetlands that were intact in the 1930s when these levies were finished, would still be largely intact today.

A wellhead in the wetlands (Photo: Paul Goyette; CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: But that's not what happened I gather. That's not all we did, because at the same time we finished those levies, oil and gas was discovered in this coastal zone, and we proceeded to go after it because there were no protections for wetlands then. Eventually 50,000 wells were permitted in this coastal zone, over 10,000 miles of canals were dredged for oil and gas, 500 miles for shipping, and we basically eviscerated this incredible delta. There've been dozens of reports that show where there was a heaviest amount of oil and gas extraction and canal dredging, we have the highest rate of land lost and subsidence. So we're fighting this massive loss of surface land, we're also subsiding, right, because we're not replenishing this land, these wetlands, I should say, and on top of that here comes global warming and sea level rise. So we're in this precarious situation where we have, according to NOAA, the highest rate of relative sea level rise of any place in the country, and one of the highest rates anywhere on the planet. So where most of the country might be looking at two feet of sea level rise by the end of the century, they're saying this area is looking at three and a half to four feet, four and a half feet because of this combination of sinking and rising seas.

Because of coastal erosion, many pipelines are now in open water. (Photo: Paul Goyette; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

MARSHALL: NOAA, of course, is the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. So your project features an online map, Bob, that illustrates the extent of the crisis through time. Why did you choose to make this so visual?

CURWOOD: This is really, the really new thing about this report on our coast. I've been covering this for years, for decades, but what the brilliant people at ProPublica did with their computer and graphic skills is they went back and took official US Geological Survey topographical maps and then aerial photographs and satellite photographs and blended them together going back to the 1930s and earlier. And then they could show you what actually happened as you move a slider across some of these pages. You'll see these pristine wetlands in the 1930s turn in some areas to open water. You'll watch as these canals came in and the place just opened up and fell apart. And, you know, writers hate to hear this: I can tell you I have been working on this for decades and people who have been reading my stories for decades say, "This is the best thing you've ever done." Well, the words are pretty much the same, but the pictures these graphics, really finally hit home as you watch this part of the state drown.

Louisiana’s coastal wetlands are importing spawning habitat for a wide variety of marine species like these blue crabs. (Photo: Mira (on the wall); Flickr CC BY 2.0)

MARSHALL: So what's been the impact of all this land loss on people living along the Gulf?

CURWOOD: Well, there are communities now that are faced with having to move. People are kind of angry and they’re stunned. And they want someone to pay to keep their communities where they are and the cost is just too high. Some communities are facing facts, they're seeing they have to move; others are hoping that the state or the federal government, someone will come to the rescue, and build higher or taller levies to protect them. But this could be the largest forced migration for environmental reasons and the history of the country.

Volunteers with the organization Common Ground Relief working to rebuild Louisiana wetlands. (Photo: Peter Lucak; Common Ground Relief)

MARSHALL: Bob, in your piece, you highlighted a couple of places that are particularly impacted by all of this. Tell me about Delacroix please.

CURWOOD: Well, Delacroix Island is a settlement about 30 miles from the French Quarter here in New Orleans that was founded back in the late 1700s, early 1800s. It's unique because it's Spanish. Back in 1780s when Spain owned this part of the world, King Philip was eager to have more settlers here, so he looked for volunteers from the Canary Islands. They moved here. They worked originally on plantations closer to the city, and then they moved down to the bayous onto the delta. The people lived there for a couple hundred of years and really into the 1950s, late ‘50s, they had very little contact with New Orleans. They had a subsistence lifestyle. They were fisherman, trappers; they picked pick moss to sell to furniture makers - Spanish moss. But the canal dredging that started in the ‘30s and ‘40s began to have an impact. They began noticing that the marshes, the wetlands they trapped were falling apart—that the lagoons and the bayous were getting wider; the lakes were getting bigger. When they want to set their traps for muskrat, nutra, mink, the traps were deeper in the water, and eventually the storms that came through basically made it impossible for them to live there full-time. So the whole ecosystem, this incredible delta that not only isolated them and kept their culture unique, but also provided their living, was being destroyed. That whole culture is gone. There’re maybe ten families living there now, and the amount of land, land once was so high and wide that bison and elk roamed it, is now about 50 yards wide on either side of the bayou, and the rest is either wetlands or open water.

The wetlands are rich in biodiversity. Here an alligator swims through the Atchafalaya Delta. (Photo: Rafael Medina; CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, Bob, how aware are Louisianans, living in other parts of the state, of these issues do you think?

MARSHALL: I think they're more aware than rest of the country. There's been a lot of media coverage here over the last...especially since Katrina. But I think the state just lived in denial in large measure because one of the major causes of land loss is the oil and gas industry.

CURWOOD: So to what extent has oil and gas, that business, been held accountable for what's happening?

Bald cypress trees are a distinctive feature of Louisiana’s swamps. (Photo: Vilseskogen; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

MARSHALL: Well, they really haven't. According to many studies, the oil and gas industry is responsible for anywhere between 36 to 60 percent of the loss. There were permits they had to get beginning in 1972 with the Clean Water Act, and state has its own permits, but they really were not forced to comply by the permits which required them to return the areas they were working in pretty much back to their original state. So instead of a backfilling these canals whenever they finished, that was not done. A lot of the waste pits that are out there were not properly taken care of.

Bob Marshall is a reporter for The Lens. (Photo: Courtesy of The Lens)

MARSHALL: In many cases, oil companies, when the well ran dry just left and left the damage there. There was a landmark lawsuit brought last year by the local flood protection authority seeking damages from 97 oil, gas and pipeline companies for wetlands loss. They're saying that without these wetlands, storm surge is higher; it's going to cost us more to keep the city in this area safe. But that provoked the ire of the state’s political establishment including the governor who promised to get the Legislature to pass laws retroactively preventing this board from suing, and they did get one through, and that's now in federal court on a constitutionality test. And we'll find out what happens there. So they really have not been held accountable for the damage done.

CURWOOD: Bob Marshall is a reporter with the Lens. Thanks for taking the time with us today.

MARSHALL: Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: You can find a link to his report at our website LOE.org.

Links

Check out more “Losing Ground” photos depicting Louisiana’s land loss crisis here.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth