September 19, 2014

Air Date: September 19, 2014

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Climate Action As A Race to the Top

View the page for this story

International climate summits to date have brought disputes and stalling not agreement and action. Host Steve Curwood discusses tha latest UN meeting and his blueprint for ending inaction with Former Colorado Senator and climate negotiator, Timothy Wirth. (07:40)

China's Rejection of GMO Corn Shipments Prompts Lawsuits

View the page for this story

Grain Traders Cargill and Trans Coastal Supply are suing biotech giant Syngenta AG over tens of millions of dollars they lost from shipments containing the company's GMO corn China rejected. Temple University law professor Greg Mandel joins host Steve Curwood to analyze the lawsuits, China’s motivation, and what this might mean for GM corn. (06:45)

Ohio Community Protests Fracking Wastewater Zoning

/ Julie GrantView the page for this story

Fracking wastewater is trucked into Ohio from Pennsylvania, processed and injected into deep wells. The Allegheny Front’s Julie Grant reports that many locals worry about earthquakes and water contamination, and argue that the state rules override citizen’s concerns about waste water well siting. (07:05)

Losing Ground in Louisiana

View the page for this story

Levees along the Mississippi river and years of oil and gas extraction have caused dramatic erosion and subsidence in Louisiana. Bob Marshall, a reporter with the New Orleans news-site The Lens, discusses the new interactive project he developed with ProPublica with host Steve Curwood and explains how the vanishing land could displace thousands of people if nothing changes. (10:55)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s trip beyond the headlines Peter Dykstra and Steve Curwood discuss the lack of railroad bridge inspection in California and question whether we’re prepared to deal with a possible tar sands oil spill in the Great Lakes. (04:30)

MIDORI Prize—Acknowledging Excellence in Biodiversity Contributions

View the page for this story

The 2014 MIDORI Prize, a prestigious award for contributions to conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity was won by, among others, Kamal Bawa, a professor at University of Massachusetts at Boston. Host Steve Curwood discusses the prize, Dr. Bawa's tropical rainforest research and the state of biodiversity in India, the U.S., and the globe. (06:40)

Mallardy

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

Much of the habitat on which Mallards and other ducks depend has been devloped or drained, leaving them short of food and safety from hunters. Writer Mark Seth Lender observes as they gather to await his arrival, and does what he can to provide for them. (02:20)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Tim Wirth, Greg Mandel, Bob Marshall, Kamal Bawa,

REPORTER: Julie Grant, Peter Dykstra, Mark Seth Lender

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. As the UN holds a climate summit in New York, a new global treaty is not in the cards.

WIRTH: The people who are arguing for a treaty are a little bit like the test dummies for automobile safety. You know, you ram the car into the wall, and then you back it up and the heads are banging around and so on. And then you ram the car into the wall again. We’re not going to get a treaty right now, so let’s figure out what we do instead.

CURWOOD: Alternative approaches to help cool the planet. Also, the growing problems associated with dumping the wastewater from fracking has some folks in Ohio worried.

HAGAN: They had that earthquake come out of Youngstown because of fracking. And we felt it up here in Shalersville, so yeah, the concern is there, that it might contaminate our well, our water. The fracking, and causing another earthquake or causing some splits in the shale.

CURWOOD: We’ll have those stories and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies – innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live.

Climate Action As A Race to the Top

Thousands gathered at the 2009 UN Climate Summit in Copenhagen, Denmark in support of global climate action. (Photo: Marc Kjerland; Flickr CC-BY-SA-2.0)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. On September 23rd, more than 120 heads of state will take time out from the opening of the General Assembly of the United Nations in New York to hold a brief Climate Summit. The session is scheduled to come on the heels of what’s being billed as the largest climate march in history on the streets of New York City, September 21st. Back in 1990, the UN enthusiastically began hammering out international climate protection agreements and treaties, but for years the results have been disappointing. Tim Wirth is a one-time Senator from Colorado, and the former President of the UN Foundation. With former Senator Tom Daschle of North Dakota, he’s written a comprehensive blueprint for how to come to an agreement that every nation can back and find beneficial. He joins us on the line to lay out his thinking.

WIRTH: First of all I think we’re at an interesting inflection point from talk to action. I mean, people are now starting to understand, I think, much more deeply the urgency of the issue, and second are starting to see that there are a great number things that they can be doing, that's in their national interest, in their economic interest. So as those two come together, I think we have an opportunity to close the gap between the urgent need to reduce carbon emissions and the political reality around the world.

CURWOOD: Now, you write that the principal elements that need to come out of a grand deal in Paris next year involve reaffirming the basic global objectives to prevent more damage to the climate and instituting firm national targets, rather than an international treaty. So what's the advantage of that?

A Global Day of Action for Climate: A mass demonstration and march on December 12th, 2009 during the UN Climate Summit in Copenhagen. Organizer intended The People’s Climate March in New York on September 21st, 2014 to be one of the biggest ever. (Photo: Greenpeace Finland from Helsinki, Finland; Wikimedia CC-BY-2.0)

WIRTH: Well, the advantage of that is pragmatism. I mean, there is no way we're going to get an international treaty. The Senate can't even ratify the basic treaty on disabilities that was brought to it, or something as palpably in the U.S. national interest as the law of the sea. How in the world do we think that the United States Senate, at this point, is going to ratify an international treaty? If that is the reality, which I think it is, then you have to figure out, well, what do we do differently? And what we’re proposing is a number of individual steps, or what we call building blocks, that have to be taken anyway, and will ultimately lead to the kind of treaty we might be able to get in five years or 10 years.

CURWOOD: What do you say to critics who say that you’ve got to have a binding agreement here—if you don't make this mandatory it won't happen?

WIRTH: Well, I mean, that's a position to take, but that's not going to happen, so why keep banging your head against the wall? You know, I think the people who are arguing for a treaty are a little bit like the test dummies for automobile safety. You know, you ram the car into the wall, and then you back it up and the heads are banging around and so on. And then you ram the car into the wall again, you know. We’re not going to get a treaty right now, so let’s figure out what we do instead.

CURWOOD: Back in Copenhagen in 2009, the United States pledged that the developed countries would mobilize $100 billion dollars a year to address what's going on with climate disruption. Without some sort of ironclad agreement, less-developed countries are pretty nervous that they're not going to see any of this money.

Renewable energy including wind power is a building block in Tim Wirth’s plan for climate action. (Photo: Alex Ferguson; Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

WIRTH: Well, I think there are two different kinds of finance in all of this. Traditionally, people have said, "Oh, this has got to come from the official government assistance, you know, from foreign aid,” and some of that's going to be needed to help countries, but much more important is mobilizing the pools of capital that are available from the private sector—that now are seeing very significant and promising markets for themselves. If you look at some of the big international financial institutions, for example, are already committing tens of billions of dollars, pledging more than that. There's lots of money around. It's a matter of mobilizing it and making sure that the rules are right, so that the rate of return that financial institutions are getting is comparable to what they're getting elsewhere. Which brings us right back to another point, this divest movement related to investments and fossil fuels: I think it's the fastest movement that I've seen in terms of climate actions by citizens across the world. Many, many groups are now saying that they are no longer going to invest in the exploration for or development of further sources of fossil fuels—we just don't need them—but let's invest instead into renewables and efficiency.

CURWOOD: So, obviously, you see your blueprint as practical, but how far do you think the necessary players - I'm thinking of the United States, China, the Europeans - how much are they aboard with this idea?

WIRTH: That's a very good question. I think were going to find out more about the United States posture at the Asia-Pacific meetings when President Obama is in China for a day or two with President Xi. None of this effect is going to happen unless a major political agreement gets reached between the United States and China. Without that, it's hard to see the maintenance and sustaining of the international momentum that's going to be necessary to hold the temperatures of the world below the 2-degree, the red line. The United States and China, I think, will be directly responsible if that does not happen.

CURWOOD: How committed do you think the White House is to this approach? They're getting sniped at ..."Oh, they're going around the U.S. Senate. Oh, there goes Obama again; he’s ignoring the will of the people."

Former Colorado Senator and President of the UN Foundation Timothy Wirth is a longtime proponent of climate action. He speaks at the 2013 National Clean Energy Summit in Las Vegas. (Photo: Courtesy of Timothy Wirth)

WIRTH: I think the Obama White House is by and large very committed to this. You see that in the very important regulations that the White House has put out for the Environmental Protection Agency. The White House also has to back this with all kinds of other measures. In there, the records are a little thinner. For example, in my home state of Colorado they're just trying to let a huge coal lease again, which would allow coal companies to go into some very, very promising public lands, take the coal out, ship it to the west coast and ship it to China, and the administration is supporting that as well. So I think their posture has to be consistent throughout, and they're not there yet.

CURWOOD: So China has announced pretty significant plans to reduce first their carbon intensity, and then they say they're going to have a national carbon trading program and such. They seem very committed in moving forward. Does that make the U.S. with its ambivalence the skunk at the picnic here?

WIRTH: Well, as the U.S. has got ambiguities about their position, so do the Chinese. That's why it's terribly important, it seems to me, that the smartest thing that the two countries could do would be to appoint a czar on each side—a very senior person who is really assistant to the President with an enormous amount of authority over the interagency process and have that person's analog figure in China. So you have two people working out their problems together and developing the analysis, developing the research, sharing the technology. These are the things that have to be done. You know, India's going to be watching very carefully, and they'll be the next one on board. And then with Brazil and South Africa and, of course, the European Union and the Japanese would be on board any kind of a deal like that, so what the U.S. and China do becomes terribly, terribly important and let's have a firm, cooperative, real leadership position from these two giant countries.

CURWOOD: Tim Wirth is a former Senator from Colorado and founding President of the UN Foundation. Thanks much for taking the time, Tim.

WIRTH: Thank you, Steve. Always a privilege.

Related links:

- More on the UN Foundation’s 2014 Climate Summit in New York

- Read former US Senators Tim Wirth and Tom Daschle’s “A Blueprint to End Paralysis Over Global Action on Climate”

[MUSIC: The Whitest Boy Alive from “Roller Coaster Ride” from Rules (Bubbles 2009)]

China's Rejection of GMO Corn Shipments Prompts Lawsuits

China rejected Syngenta’s GMO corn, which sparked lawsuits from Cargill and Trans Coastal Supply. (Photo: *MarS; Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Since November, China has been rejecting boatloads of grain from the U.S. with trace amounts of a type of genetically engineered corn not approved in the People’s Republic. These rejections of corn have cost U.S. agribusiness nearly $3 billion dollars. Now, the agricultural trading giants Cargill and Trans Coastal Supply are suing Syngenta, the company that created this particular strain of corn, because it failed to get import approval from China. The two exporters together claim more than $130 million dollars in losses. It’s not obvious that Syngenta is to blame, because bulk transport and processing can co-mingle different varieties of corn. But even farmers who didn’t plant the Syngenta GMO corn in question could have wound up with trace amounts in their harvests because the wind blows corn pollen from field to field. Greg Mandel is a Professor of Law at Temple University who studies emerging technologies and intellectual property. Welcome to Living on Earth.

MANDEL: Thank you for having me, Steve. It's a pleasure to be here.

CURWOOD: Help us understand this backstory a little bit better. These companies have been shipping Syngenta’s products all over the world including China for years. What's the source of this sudden conflict?

MANDEL: Well, Syngenta got this particular crop, which is referred to as Agrisure Viptera, to be deregulated; that means it could be freely commercialized, sold, harvested, transported in the United States, but that regulatory approval doesn't necessarily affect approval in other markets. At the time they started commercializing the corn product, they did not yet have approval in most foreign markets, but were seeking it. Since that time, they've gotten approval in Canada, Mexico, and EU, but not in China.

Grain Trader and Distributor Cargill’s logo (Photo: skhakirov; Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Where's the balance of this dispute? Is this being raised by health and safety concerns, or is China just messing with us?

MANDEL: [LAUGHS] China's doing something. I would doubt very much that there are serious health and safety concerns about this product. This is not a product, for instance, that ran into significant hurdles in the other markets where it's been approved. So, one possibility is that China is just engaging in a little bit of trade pressure. We know that there have been some negotiations going on: the Secretary of Agriculture, I believe, went over to China to try to discuss this. China's certainly trying to develop their domestic GM crops. There's some other possibilities: obviously there could be just sort of a level of dysfunction in China's regulatory system. We know that some shipments of corn, which again almost definitely contain trace elements of this Syngenta Viptera, have been allowed to enter China, others have not. There are stories about some ports being more stringent, others being not. And the other thing going on is, of course, China's domestic corn market generally. Its growers apparently recently harvested a huge corn crop, and the Chinese government supports that industry significantly. And so there again maybe some market forces are leading to this action. All of that is guesswork. All of those are plausible theories, but I have not heard from anyone who sort of has a clear idea of exactly what's going on. And the Chinese regulatory entities have not said anything about it either.

China ports banned shipments containing GMO corn from the United States. (Photo: Bigstockphoto)

CURWOOD: Since these products haven't been approved in China, how is it that the grain companies can put the blame for their losses on Syngenta? They must've known that they weren't approved there.

MANDEL: Both of the actions that have been filed make a lot of claims about different things that Syngenta did wrong. But at the bottom of both lawsuits is essentially a negligence claim that Syngenta acted negligently towards these parties or towards the entire corn market. The grain companies are arguing that by negligently commercializing a biotech product that had not received regulatory approval in all major markets, Syngenta knew or should have known that that would comingle out in the market with approved products and non-genetically modified products and that trace amounts would begin to show up in shipments all around the world.

CURWOOD: So how surprised are you to see these lawsuits?

MANDEL: I was definitely surprised to see them. The plaintiffs are definitely facing an uphill battle. I’ve talked to a couple other people, and no one's been able to identify a lawsuit that would provide precedent for these kinds of lawsuits where the plaintiff is claiming that a party engaged in activities that were entirely legal, but affected a market in such a way that it caused damage, and that those actions were negligent. So it would be pretty surprising for Syngenta to be found liable on these bases and that made it surprising that these lawsuits were actually filed.

Gregory N. Mandel is a law professor with Temple University. (Photo: Courtesy of Temple Law School)

CURWOOD: So if Cargill and Trans Coastal win - recover some of the money they say they lost because China won't accept some of these shipments - what kind of impact would that have in the GMO-producing agribusiness?

MANDEL: From the GMO producers’ perspective, it would essentially mean that GMO producers would have to get regulatory approval in some significant percentage of the world's markets for their products before they could commercialize in the United States. Although, on the other hand if Syngenta is successful in this case, it might strengthen the hands of the producers and make them feel more confident about launching products prior to worldwide registration, in effect.

CURWOOD: So at the end of the day, what do you think will happen with this lawsuit? How likely is it that these giant companies, Cargill, Trans Coastal, Syngenta, will settle things out of court.

MANDEL: It's very likely they'll settle. Cargill and Syngenta had been in some discussions before, and those discussions fell apart. Cargill may be looking for some assistance in sharing the huge losses they're facing, but I do think it's unlikely that these cases actually go to trial.

CURWOOD: Greg Mandel is a Professor of Law at Temple University. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today, Professor.

MANDEL: Thank you for having me Steve, I enjoyed it.

Related links:

- Syngenta’s statement regarding Cargill’s lawsuit

- Cargill’s statement regarding the lawsuit

- Trans Coastal's complaint filed in Illinois' Federal District court

- Cargill sues Syngenta over GMO corn rejection by China

- Syngenta slammed with a lawsuit from Trans Coastal Supply in the wake of Cargill’s.

[MUSIC: Ásgeir from “In The Silence” from Rules (One Little Indian 2014)]

CURWOOD: Coming up: A fall-out from fracking. Millions of gallons of wastewater and earthquakes. That’s just ahead. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Johnny Hodges with the Duke Ellington from “I Got It Bad And That Ain’t Good” from The Art of Jazz Saxophone: Classic Sounds (Laserlight Jazz 1997)]

Ohio Community Protests Fracking Wastewater Zoning

Stallion Oilfield Holdings' Attorney Robert Ryan, Regional Vice President Cameron Simon and Regional Operations Manager Randy Ile, at a well pad in Portage County, Ohio. (Photo: Julie Grant)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. As natural gas production continues to spread across the country, some citizens are trying to fend off drilling rigs and waste sites in their backyards. While gas companies say they already face tough state regulations, that oversight doesn’t always ease residents’ fears. As Ohio quickly becomes a go-to destination for the nation's frackwaste, some people worry about earthquakes and water contamination, and argue the state has taken away their authority to decide whether oil and gas waste should be allowed in their backyards. Julie Grant reports for the public radio program the Allegheny Front, and has this story from a rural county that’s the biggest dumping ground in Ohio.

[INDUSTRIAL NOISE]

GRANT: This is the sound of dirty water flowing from a big, industrial truck into storage tanks. We’re in the countryside in Portage County, Ohio, in the midst of cornfields and a horse farm. When you drive in further, you see the large green storage tanks, the pump house, and the wellhead.

Retired University Professor Gwen Fisher has become an activist for community rights at injection well sites. (Photo: Julie Grant)

ILE: He’s just about unloaded there. See the hose shaking? That means that hundred barrel of water is in the system now.

[INDUSTRIAL NOISE]

GRANT: Randy Ile operates this well for a Texas company, Stallion Oilfield Holdings. He says the water was trucked here from Pennsylvania. It’s wastewater from an oil and gas well. The wastewater will spend the next few days moving through a series of 12 large tanks.

ILE: And then the last thing it does is come into the pump house in here, and it comes through a 25-micron filter and then through a ten-micron filter. So it’s basically as clean as...down to 10 microns.

GRANT: What are you filtering?

ILE: Sediment of any kind: particles of rock, or anything like that.

A truck carrying wastewater from oil and gas operations in Pennsylvania unloads at a well site in Portage County, Ohio. (Photo: Julie Grant)

GRANT: Ile says any radioactive material is trucked to special waste sites, but the rest stays here. Once it’s filtered, the wastewater is pumped into the injection well.

ILE: This is the well.

GRANT: It doesn’t look like much—some pipes in the ground, with a pressure meter attached. Ile says they use high pressure to push the wastewater down 3500 feet, and this is what has many residents who live near this and the 17 other frack-waste disposal wells in this County concerned. Mary Hagan started worrying about the water in her family’s well last winter, when the tinsel on her Christmas tree started to shake.

HAGAN: They had that earthquake come out of Youngstown because of fracking, and we felt it up here in Shalersville, so yeah. The concern is there, that it might contaminate our well, our water. The fracking, and, causing another earthquake or causing splits in the shale.

Stallion Operations Manager in Portage County, Ohio Randy Ile holds up 25 and 10 micron filters, showing how they clean the frack wastewater before sending it down the well. (Photo: Julie Grant)

GRANT; Earlier this year, Ohio regulators acknowledged that some fracking operations near Youngstown, about 45 minutes east of here, caused earthquakes. Hagan brought a jar of water from her well to a monthly water-monitoring program held by concerned citizens in the area. They say 500 million gallons of fracking wastewater will be dumped in their county this year. Gwen Fisher is a retired university professor. She worries that the disposal wells will fail, the pipes will leak, or the concrete surrounding them will crack, and the waste, laced with chemical and possible radioactivity, will contaminate their drinking water.

FISHER: Everybody around these injection wells in these rural areas lives on their water well. If it goes bad, they’re going to have to buy water.

GRANT: In Pennsylvania, the state has confirmed more than 240 cases where oil and gas operations have contaminated drinking water. Kathleen Chandler is a Portage County Commissioner. She worries when she sees truck after truck carrying waste into the county, and there’s nothing she can do to about it.

CHANDLER: We have no control at the local level. The state took away our control.

Ohio regulates how much pressure can be used at injection wells. (Photo: Julie Grant)

GRANT: Ten years ago, Ohio changed its zoning laws. It took control of zoning of oil and gas operations away from local communities, and gave authority to the state department of natural resources. Pennsylvania tried to limit local zoning rights around oil and gas operations, as part of Act 13. But late last year, the state Supreme Court struck it down--maintaining local control. New York courts have also upheld the rights of local governments to regulate fracking. Randy Roberts is an attorney for Houston-based Stallion Oilfield, which owns three injection wells in Ohio’s Portage County. He says they’re trucking waste here because of the geology. The layers of underground rock that are better for wastewater storage are easier to access here, than in Pennsylvania’s hilly Appalachian basin. Roberts knows some people don’t like it, but he says Ohio’s uniform state zoning regulations are also attractive.

ROBERTS: I’m not trying to be difficult here, but I would like to think that Ohio has made a pitch to be relatively benign. They do not make regulations just for the sense of making regulations, but they want us to do our jobs. They come out here and inspect us and then they leave us alone, if they find we’re doing our jobs.

GRANT: But some Ohio communities are trying to assert their rights. People in the city of Kent, in Portage County, will vote on something called a community bill of rights this November. It’s an attempt to regain local rights around energy production sites. Five miles east, the city of Munroe Falls has a case pending before the Ohio Supreme Court. They’ve argued that the home rule law in the Ohio constitution overrides the state’s zoning law. Community activist Gwen Fisher says her husband sees this problem all the time. He sits on the local township board, which is in charge of most zoning decisions.

Concerned citizens can bring water from their wells to a monthly water monitoring program. (Photo: Julie Grant)

FISHER: He can spend hours discussing with his fellow board members whether or not somebody can build a fence, or keep chickens, or put up a sign. And then the next day their neighbor could have leased land, and they could have a three-to eight-acre well pad pretty close to their house, or a pipeline, and have no choice about it.

GRANT: Fisher says the country roads near them suddenly become industrial sites with over-sized trucks regularly rumbling through. This issue, of whether states or local governments should control zoning around oil and gas operations, is being debated in eight states around the country. People are deciding if the new energy and possible economic growth are worth the loss of control and huge changes it brings to the countryside. Randy Roberts of Stallion Oilfields says it makes sense to decide energy development at the state level.

ROBERTS: It’s akin to the federal government regulating the drugs. The FDA regulates drugs; each county doesn’t regulate what drugs you can take. And it makes more sense for the state to do it than to have part-time zoning board people decide whether someone can drill for oil and gas. They’re not educated in that area, and they don't have time to get educated in that area.

GRANT: Energy companies, business groups and the state argued against Munroe Falls and other cities before the Ohio Supreme Court in February. They’re expecting a decision at any point. Meanwhile, the state continues to regulate injection wells that accept frack waste from Pennsylvania.

CURWOOD: That report came from Julie Grant of the Allegheny Front.

Related links:

- Read more about how Ohio locals are attempting to control wastewater injection zoning on Allegheny Front’s page

- Listen to how wastewater injection is causing earthquakes

- Radioactive Risks associated with Fracking Wastewater

[MUSIC: Wilco –“Pot Kettle Black” from Yankee Hotel Foxtrot (Nonesuch 2002)]

Losing Ground in Louisiana

The network of canals cut through the marshes to enable oil and gas extraction has driven Louisiana’s coastal land loss. (Photo: John McQuaid; Flickr CC2.0)

CURWOOD: Louisiana is growing smaller and smaller, thanks to changes in the Mississippi delta that were designed to increase flood protection and enhance oil and gas production. Bob Marshall has been covering coastal land loss in Louisiana for decades. He’s now a writer with the Lens, a non-profit news site in New Orleans. He recently collaborated with ProPublica to put out a graphically enhanced report called Losing Ground. Complete with dynamic maps and images, Losing Ground shows just how much of Louisiana’s wetlands have been eaten up by the Gulf of Mexico. Bob Marshall joins us now. Welcome to Living on Earth.

MARSHALL: My pleasure to be here.

CURWOOD: So the project is called "Losing Ground". How significant is this land loss crisis? How quickly are we Losing Ground down in Louisiana?

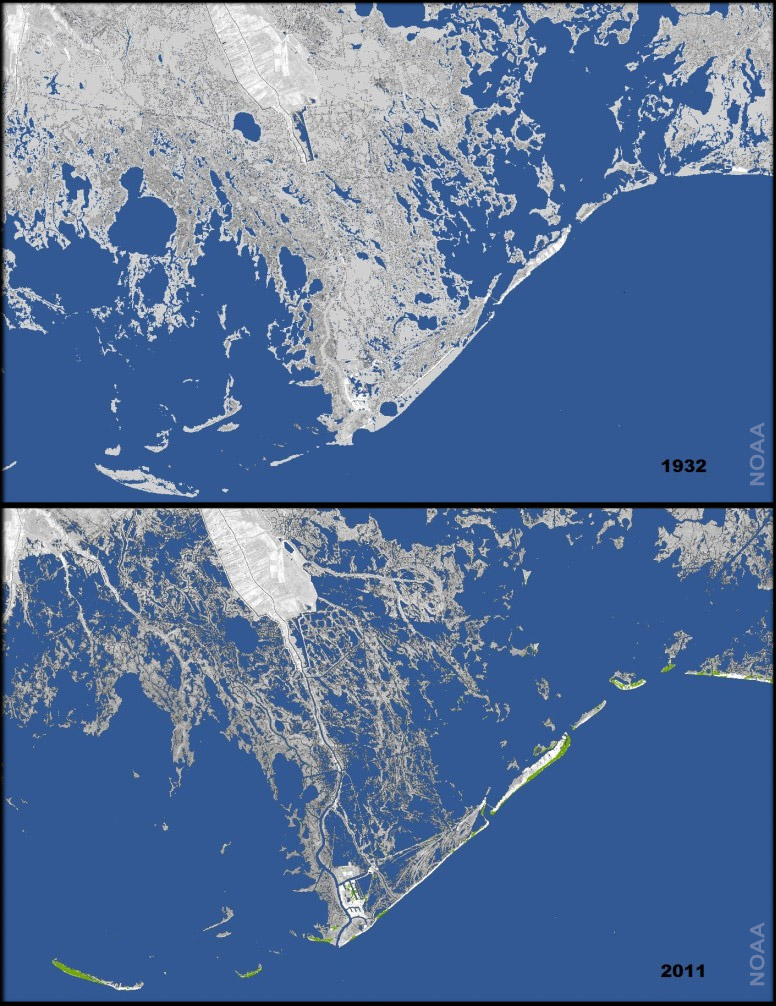

Image showing land loss since 1932 (Photo: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; public domain)

MARSHALL: Well, right now they're losing it at about 16 square miles a year. They like to say a football field every 48 minutes, but if you go back 20 or 30 years ago we were losing as much as 50 square miles a year. So we've lost about 2,000 square miles since the mid-1930s, and there's very little left now in southeast Louisiana.

CURWOOD: Now, I gather a lot of this has to do with the way people have controlled the Mississippi River over the years. Describe that process for me.

MARSHALL: Well, this whole area of the state, all of south Louisiana, really, from Mississippi to Texas, was built by the Mississippi River. It's delta-building process going back about 7,000 years when the end of the last glacier period. You know, when the river hits this flat plain, it slows down and all the sediment it's carrying begins to fall out. And it wasn't just the main stem of the river, it was all these distributaries that peeled off the river on its delta plain. So there was this big, really spider web of distributaries carrying all this freshwater and sediment, and during the spring floods, the river would come over its banks, and over the distributaries banks and spread this—really, nature's cement, if you want to call that—out all across this area. And so that process was still going on when Europeans arrived, and when New Orleans was founded in 1718, they were still building land out in the Gulf of Mexico. And everything went along as nature intended it until we began developing along the river, and people began putting up levies so that they wouldn't get flooded by this river every spring.

Many of the people living in wetland communities have already been forced to migrate because of land loss. (Photo: Alicia Lee; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So what did the levees do to the river exactly? Why did it make it lose land?

MARSHALL: Well, the levees block the river from spreading more settlement out on its delta, and so when a river can't get back out to replenish its delta, that delta begins subsiding. So there were levies on the Mississippi really going back to the 1850s, but after the Great Flood of 1927 when most of the Mississippi River Valley from Illinois to Louisiana was flooded, Congress said, "Never let this happen again." And so the Corps built these great levies, and they put the river in a straitjacket permanently blocking the river from getting back to its delta to replenishing this land. If that's all we had done, the researchers say that the delta would have been subsiding at an infinitesimal rate, milliliters per year, and the wetlands that were intact in the 1930s when these levies were finished, would still be largely intact today.

A wellhead in the wetlands (Photo: Paul Goyette; CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: But that's not what happened I gather. That's not all we did, because at the same time we finished those levies, oil and gas was discovered in this coastal zone, and we proceeded to go after it because there were no protections for wetlands then. Eventually 50,000 wells were permitted in this coastal zone, over 10,000 miles of canals were dredged for oil and gas, 500 miles for shipping, and we basically eviscerated this incredible delta. There've been dozens of reports that show where there was a heaviest amount of oil and gas extraction and canal dredging, we have the highest rate of land lost and subsidence. So we're fighting this massive loss of surface land, we're also subsiding, right, because we're not replenishing this land, these wetlands, I should say, and on top of that here comes global warming and sea level rise. So we're in this precarious situation where we have, according to NOAA, the highest rate of relative sea level rise of any place in the country, and one of the highest rates anywhere on the planet. So where most of the country might be looking at two feet of sea level rise by the end of the century, they're saying this area is looking at three and a half to four feet, four and a half feet because of this combination of sinking and rising seas.

Because of coastal erosion, many pipelines are now in open water. (Photo: Paul Goyette; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

MARSHALL: NOAA, of course, is the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. So your project features an online map, Bob, that illustrates the extent of the crisis through time. Why did you choose to make this so visual?

CURWOOD: This is really, the really new thing about this report on our coast. I've been covering this for years, for decades, but what the brilliant people at ProPublica did with their computer and graphic skills is they went back and took official US Geological Survey topographical maps and then aerial photographs and satellite photographs and blended them together going back to the 1930s and earlier. And then they could show you what actually happened as you move a slider across some of these pages. You'll see these pristine wetlands in the 1930s turn in some areas to open water. You'll watch as these canals came in and the place just opened up and fell apart. And, you know, writers hate to hear this: I can tell you I have been working on this for decades and people who have been reading my stories for decades say, "This is the best thing you've ever done." Well, the words are pretty much the same, but the pictures these graphics, really finally hit home as you watch this part of the state drown.

Louisiana’s coastal wetlands are importing spawning habitat for a wide variety of marine species like these blue crabs. (Photo: Mira (on the wall); Flickr CC BY 2.0)

MARSHALL: So what's been the impact of all this land loss on people living along the Gulf?

CURWOOD: Well, there are communities now that are faced with having to move. People are kind of angry and they’re stunned. And they want someone to pay to keep their communities where they are and the cost is just too high. Some communities are facing facts, they're seeing they have to move; others are hoping that the state or the federal government, someone will come to the rescue, and build higher or taller levies to protect them. But this could be the largest forced migration for environmental reasons and the history of the country.

Volunteers with the organization Common Ground Relief working to rebuild Louisiana wetlands. (Photo: Peter Lucak; Common Ground Relief)

MARSHALL: Bob, in your piece, you highlighted a couple of places that are particularly impacted by all of this. Tell me about Delacroix please.

CURWOOD: Well, Delacroix Island is a settlement about 30 miles from the French Quarter here in New Orleans that was founded back in the late 1700s, early 1800s. It's unique because it's Spanish. Back in 1780s when Spain owned this part of the world, King Philip was eager to have more settlers here, so he looked for volunteers from the Canary Islands. They moved here. They worked originally on plantations closer to the city, and then they moved down to the bayous onto the delta. The people lived there for a couple hundred of years and really into the 1950s, late ‘50s, they had very little contact with New Orleans. They had a subsistence lifestyle. They were fisherman, trappers; they picked pick moss to sell to furniture makers - Spanish moss. But the canal dredging that started in the ‘30s and ‘40s began to have an impact. They began noticing that the marshes, the wetlands they trapped were falling apart—that the lagoons and the bayous were getting wider; the lakes were getting bigger. When they want to set their traps for muskrat, nutra, mink, the traps were deeper in the water, and eventually the storms that came through basically made it impossible for them to live there full-time. So the whole ecosystem, this incredible delta that not only isolated them and kept their culture unique, but also provided their living, was being destroyed. That whole culture is gone. There’re maybe ten families living there now, and the amount of land, land once was so high and wide that bison and elk roamed it, is now about 50 yards wide on either side of the bayou, and the rest is either wetlands or open water.

The wetlands are rich in biodiversity. Here an alligator swims through the Atchafalaya Delta. (Photo: Rafael Medina; CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, Bob, how aware are Louisianans, living in other parts of the state, of these issues do you think?

MARSHALL: I think they're more aware than rest of the country. There's been a lot of media coverage here over the last...especially since Katrina. But I think the state just lived in denial in large measure because one of the major causes of land loss is the oil and gas industry.

CURWOOD: So to what extent has oil and gas, that business, been held accountable for what's happening?

Bald cypress trees are a distinctive feature of Louisiana’s swamps. (Photo: Vilseskogen; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

MARSHALL: Well, they really haven't. According to many studies, the oil and gas industry is responsible for anywhere between 36 to 60 percent of the loss. There were permits they had to get beginning in 1972 with the Clean Water Act, and state has its own permits, but they really were not forced to comply by the permits which required them to return the areas they were working in pretty much back to their original state. So instead of a backfilling these canals whenever they finished, that was not done. A lot of the waste pits that are out there were not properly taken care of.

Bob Marshall is a reporter for The Lens. (Photo: Courtesy of The Lens)

MARSHALL: In many cases, oil companies, when the well ran dry just left and left the damage there. There was a landmark lawsuit brought last year by the local flood protection authority seeking damages from 97 oil, gas and pipeline companies for wetlands loss. They're saying that without these wetlands, storm surge is higher; it's going to cost us more to keep the city in this area safe. But that provoked the ire of the state’s political establishment including the governor who promised to get the Legislature to pass laws retroactively preventing this board from suing, and they did get one through, and that's now in federal court on a constitutionality test. And we'll find out what happens there. So they really have not been held accountable for the damage done.

CURWOOD: Bob Marshall is a reporter with the Lens. Thanks for taking the time with us today.

MARSHALL: Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: You can find a link to his report at our website LOE.org.

Related links:

- Check out more “Losing Ground” photos depicting Louisiana’s land loss crisis here.

- Read more from Bob Marshall at the Lens.

[MUSIC: Kings of Convenience “The Passenger” from Quiet is the New Loud (Astralwerks 2001)]

CURWOOD: Coming up: We talk with a conservation champion about his work – and the major international prize it won him. That's just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems provides building technologies and supplies container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food, and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Zoot Sims from “Come Rain or Come Shine” from The Art of Jazz Saxophone: Classic Sounds (Laserlight Jazz 1997)]

Beyond the Headlines

Until it makes some planned hires, California doesn’t have any state inspectors to monitor the safety of bridges that oil trains go over every day. (Photo: Russ Allison Loar; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Time now to head beyond the headlines with the man who’s always searching out unusual and often ignored stories, that’s Peter Dykstra. He’s publisher of Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org, and the DailyClimate.org. He joins us from Conyers, Georgia. Hey, Peter, what’s up today?

DYKSTRA: Well, hi, Steve. Let’s start off with something you’ve covered before: the shipping oil and coal by railroad.

CURWOOD: And the dangers there, I mean, there are a lot of problems.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, the coal industry’s domestic business is declining, so they’re increasingly looking to ship coal to seaports for export around the world. And the domestic oil boom has put huge demand on rail lines for shipping to oil refineries. All this got a reporter named Matthias Gafni to thinking. He writes for the Contra Costa Times in California, where they have seaports and export terminals and a whole lot of railroads. But the state of California has an aging railroad infrastructure and absolutely no staff or no program to inspect all those railroad bridges.

CURWOOD: Wait, so there’s nobody checking out railroad bridges in the most heavily populated state in the country?

DYKSTRA: Well, not exactly. The rail lines are responsible for their own inspections, and there’s one Federal inspector who works California.

CURWOOD: Oh, so, an honor system, plus one inspector?

DYKSTRA: Well, still not exactly, the one federal inspector also works ten other states, and bear in mind that California is earthquake central. The 6.0 quake in the Napa Valley back in August was a little bit of a wake-up call, and now California is looking to hire its first-ever two railroad bridge inspectors and make its first-ever list of rail bridges that need inspecting. I will say this, at least we’re not reading about the inspection problem after a bridge collapse.

CURWOOD: Well, that’s a good point and let’s hope we won’t. What do you have for us next?

DYKSTRA: Well, it’s potential accidents waiting to happen, part two: the U.S. Coast Guard said this past week that if there’s a major oil spill in the Great Lakes, they and other agencies are unprepared to respond to it.

CURWOOD: So in this case, it’s not a reporter waving the red flag, but the government itself, huh?

A U.S. Coast Guard Admiral says we would be unable to deal with the cleanup if a 60-year-old pipeline that's carrying tar sands oil were to spill into the Great Lakes. (Photo: Coast Guard News; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Right. The Admiral in charge of the Coast Guard’s Great Lakes District said that oil pipelines running under the Lakes near Detroit, near Buffalo, under the Straits of Mackinac, some of these pipelines are over 60 years old. And of course there’s oil barges running on the Lakes. They could spill “heavy oil” and overwhelm the ability to respond and contain a spill.

CURWOOD: And of course they’re still dealing with the tar sands oil spill from a pipeline break in the Kalamazoo River four years ago. So, what’s the solution here?

DYKSTRA: Well, the bottom line is they don’t have a solution, but for now, the conversation between the oil companies, environmentalists, government folks and other stakeholders has started. And just like with the railroad bridges, at least we’re talking about the potential disaster before it happens.

CURWOOD: Well, let’s turn now to history. What do you have for us from the history vault for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Well, it’s hard to believe that it’s been 35 years since one of the biggest, star-studded, celebrity-soaked environmental events in history: the “No Nukes” concerts in New York City. There were some of the biggest rock and roll names of the era: Crosby Stills & Nash, Jackson Browne, Bonnie Raitt, and the Boss, Bruce Springsteen. The Three Mile Island near-meltdown had just happened in Pennsylvania, and a group called MUSE – Musicians United for Safe Energy – staged a series of shows in Madison Square Garden and an outdoor rally that drew almost 200,000 people.

CURWOOD: Yeah, and you have to wonder what all those rock stars think of what’s happened in the 35 years since.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, or what’s not happened. For starters, almost all of the headliners from the show are still active in both music and politics, and one of the organizers, John Hall – he was the front man for the band Orleans – ended up serving two terms in Congress starting in 2006. He represented, appropriately enough, the New York state district that includes the site of the Woodstock concert.

CURWOOD: So, that’s the story of the performers, but what about the energy picture?

DYKSTRA: Well, all that “Safe Energy” the musicians united for has grown lately, but I don’t think anyone on that stage 35 years ago would be pleased with the rate of progress for solar and wind. Nuclear power went into a deep slump; there have been no new U.S. plants completed for decades. There have been no huge domestic nuclear power accidents. And now there are some new plants under construction here in the Southeast, but we still haven’t figured out how to store nuclear waste safely.

CURWOOD: And, of course, we’ve seen disasters at Chernobyl and Fukushima.

DYKSTRA: Right, and in fact, many of these same performers reunited a few years ago to raise money for Fukushima victims.

CURWOOD: Thank you, Peter. Peter Dykstra is publisher of Environmental Health News – that’s EHN.org – and DailyClimate.org. Talk to you soon, Peter.

DYKSTRA: All right, Steve, thanks. We’ll talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there’s more on these stories at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Read Matthias Gafni’s story on the lack of California railroad regulation in Contra Costa Times.

- Keith Matheny’s story about Coast Guard preparedness for a Great Lakes Oil spill

[MUSIC: Crosby, Stills & Nash, “You Don’t Have To Cry” from No Nukes: The Muse Concerts for a Non-Nuclear Future (Elektra 1979)]

MIDORI Prize—Acknowledging Excellence in Biodiversity Contributions

CURWOOD: Species are disappearing at a rate unprecedented in recent times - a crisis that’s so severe some call it the sixth mass extinction. But there are heroes in our time working to preserve vital ecosystems, and to recognize these people, there’s the MIDORI Prize for Biodiversity. Every two years, the UN Convention on Biological Diversity chooses honorees to receive a wooden plaque and $100,000 U.S. dollars to support their work. The winners of the 2014 prize range from a Venezuelan expert in llamas, alpacas, and vicuñas, to a Ghanaian leader of the international dialogue on biodiversity, and a champion of conservation in India, Dr. Kamal Bawa. Dr. Bawa is also Distinguished Professor of Biology at the University of Massachusetts at Boston, and he came into our studio. Welcome to the program.

BAWA: Thank you.

CURWOOD: So, congratulations, professor!

BAWA: Thank you.

CURWOOD: So you get a wooden plaque and $100,000 dollars. You're going to give away the plaque and keep the $100,000 dollars, I imagine. [LAUGHS]

BAWA: [LAUGHS] Well, already, a number of claims have been filed against the $100,000 dollars: There is family; there is this environmental think tank that I established in India. Two years ago, I had won a larger prize that is $170,000 and I had given it all to Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment- a mouthful but the acronym is ATREE. So, I suspect in this case, too, much of the money would go to ATREE.

Dr. Bawa is a Distinguished Professor of Biology at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, and President of ATREE in Bangalore, India. (Photo: Courtesy of Dr. Kamal Bawa)

CURWOOD: So ATREE, I gather, trees are a special passion of yours. Why are trees so important?

BAWA: Trees are actually the main element of the major biological communities we find on Earth, and that's forests. I started working in Central American forests, primarily in Costa Rica. I was interested in these rainforests, in terms of trees, how do they reproduce? As we know, tropical rainforests are full of a large number of species. Two-thirds of all plant and animal species occur in the tropics, so when you have a very large number of species, individuals of a given species are scattered in the forest—two individuals of the same species maybe as far as one kilometer. So the question is, how are they reproducing? From where do they get pollen? Are they cross-pollinating or are they self-pollinating? And I was interested in those mechanisms, and I discovered actually that trees are cross-pollinated. There's no problem in having the pollen move from one tree to another tree even though they might be far apart by a wide variety of pollinators: bats, birds, bees.

CURWOOD: So in other words, trees can date another tree across town.

BAWA: Absolutely. Yes, and they're very good at that. [LAUGHS]

Costa Rica, where Dr. Bawa researched the reproduction of trees in tropical rainforests, is home to an astoundingly diverse array of organisms. (Photo: bayucca; Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] You focus primarily on whole ecosystems. Why?

BAWA: Working with trees, I was not particular interested in any given species of trees. I was working in the whole community. At that time there was a realization that there’s these biological interactions that are very critical in giving communities an entity that is larger than sum of its parts. Many of us also saw a very large-scale destruction of forests, and we started to wonder about the conservation of forests. Conservation is a sort of a social, economic, and political issue. It was a challenge at that time; it remains a challenge now.

CURWOOD: So how are we doing in this battle to save biological diversity on the planet? Winning? Losing? Holding our own?

BAWA: I think we're holding our own. I think there might be some improvement in some places. In other places there might be decline. We can't generalize at the global level. For example, in Brazil, the rates of deforestation have come down very significantly, but then there are other places, some places in Africa, where the rates of deforestation has gone up. Some people believe that as there is economic growth, people are better off, and we probably have better chances of conserving biodiversity.

Deforestation threatens the biological diversity found in tropical rainforests. (Photo: Wakx; Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: How optimistic are you about the biodiversity in India at this point, protecting it?

BAWA: I tell people I have to be optimistic; otherwise if I get up and I'm not optimistic I don't have any work to do. But seriously, I am optimistic. I think India is unique, despite the fact that it's a nation of almost 1.2 billion people, most of those people are very poor, has managed to conserve a very substantial amount of biodiversity. India has protected areas that account for about 150,000 square kilometers, and some would like to see that area doubled. And there's still a very large amount of biodiversity, which is of global significance.

CURWOOD: Before you go, can you give us some advice here please in United States about what you see as some top priorities for us to protect our biological diversity?

BAWA: I think we have to have a very comprehensive and interdisciplinary approach. We have to make sure that we are reaching the younger generation and civil society as a whole. I think we have to make certain that there is good exposure to the environment, to outdoors, and we have to reach people at a very young age. And just like in other parts of the world, we have to be very good in consensus making. And fortunately, I think our long history of democracy and democratic processes would allow us to do that.

Dr. Bawa calls for early exposure to the natural environment as one way to preserve biological diversity. (Photo: Gwoehl; Wikimedia Commons)

CURWOOD: So how well are we doing as Americans in meeting those opportunities?

BAWA: I think our record is good in some respects and in other respects it's not good. I think our policies are very well crafted, and I think in many cases we are doing a number of things at the local level, at the state level, I think issues like climate change, I think people are looking at the US to be a leader. And when people hear that there are many people who don't believe in climate change issues at the very highest levels of government, that doesn't help us.

CURWOOD: Kamal Bawa is one of the 2014 Midori prizewinners. He's a Professor at the University of Massachusetts in Boston and President of ATREE in Bangalore, India. Thanks so much for taking the time today.

BAWA: Thank you.

Related links:

- Discover more about the MIDORI Prize for Biodiversity and this year’s recipients

- Visit Dr. Kamal Bawa’s site

- Learn about the organization Dr. Bawa founded, ATREE (Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment)

Mallardy

A flock of Mallard drakes takes to the air when writer Mark Seth Lender arrives. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: Much of the habitat on which mallards and other ducks depend has been taken from them. And now it’s duck hunting season in parts of the U.S., and for mallards there is no safe place. Writer Mark Seth Lender does what he can to make up for it. He sends us this perspective from the other side of the guns.

Drakes and hens are annoyed, querulous and impatient for food that has not yet arrived. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

LENDER: Mallards are gathering, hungry, complaining, up before sunrise and nothing in the belly.

Soon they will separate, drakes to the one side. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

One calls—a loud descending voice like an old man railing against condition and age. The others mumble under their breath, annoyed, querulous, impatient for the food that has not arrived. Anxious for the giver to come yet mistrustful. A cry goes up and they fly a distance when they see him, even though they know him.

They are wise not to trust.

Hens to the other side. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

Soon they will separate: Drakes to the one side, molting together into winter iridescence, night sky blue and brilliant green fire. Hens to the other side, drab in the brown that hides them but for that flash of purple deep as a welder’s arc and a final daub of white. Soon they will leave, these two drawn lots, on different days weeks apart but not toward a different route or result. They will be shot with equanimity all along the way, in great number, on their endless perilous journey seeking south.

Lender provides grain for hungry ducks. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

But while they are here, I provide. I stand in place of the estuary that has been rerouted, water grass that was drowned, wild rice turned under, beaches walled off deep of the high tide mark and the sound of empty shells rolling in the back wash. I am the Source now, come stumbling, and blurry as the cold ground fog laid down on the earth. I come every day. As if their lives depend on it. As if my life depends on it.

Lender comes each day to feed the ducks, and they settle down for breakfast. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

And it does. And it does.

Lender observes as ducks gather during the fall, before a long migration south. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: Writer Mark Seth Lender observes that when mallards are feeding, they literally talk to each other. To see Mark’s photographs of the mallards he feeds, make way to our website. LOE.org.

Related link:

More of Mark Seth Lender’s work on his website

[WOMEN SINGING]

CURWOOD: We leave you this week with sounds of the annual Reed Dance in Swaziland. Some 80,000 young women and girls, traditionally all virgins, recently converged on the royal village in Swaziland. Wearing brightly colored beaded headbands and very short beaded skirts, they waved reeds, sang and danced topless for the Queen Mother and King Mswati the third, who usually chooses a new bride at the event.

[WOMEN SINGING]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb recorded these maidens singing and dancing. The new bride is reportedly a 19 year-old beauty pageant winner.

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jenni Doering, Lauren Hinkel, Jake Lucas, and Jennifer Marquis all help to make our show. James Curwood engineered today’s show, with help from Karlyn Daigle. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more. www.stonyfield.com.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth