Capitalism vs. The Climate

Air Date: Week of September 26, 2014

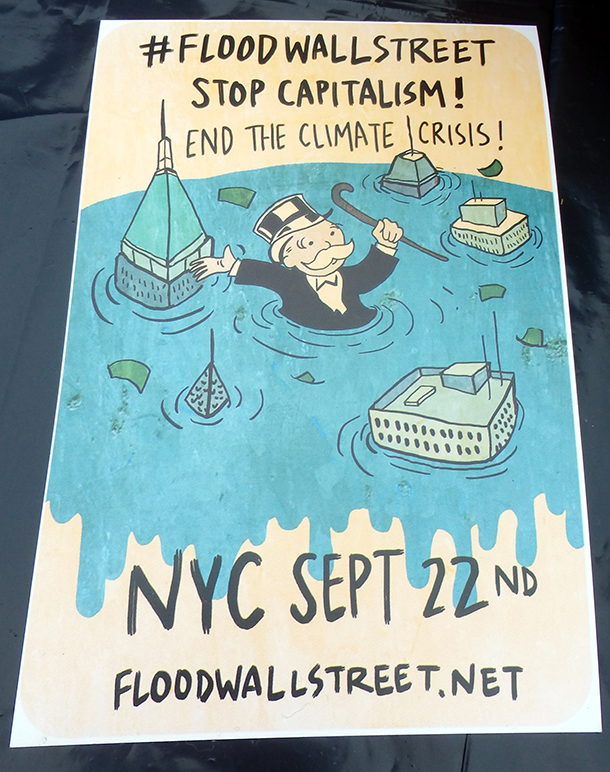

Klein spoke at the Flood Wall Street event on September 22nd, highlighting how a broken capitalist economy contributes to the climate crisis. (Photo: The All-Nite Images; Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

Naomi Klein, a best-selling author, social critic and climate activist, attended the public demonstrations of Climate Week 2014 events in New York. She sits down with host Steve Curwood to discuss her new book, This Changes Everything: Capitalism versus the Climate, which argues that global warming is largely driven by globalization and unregulated free trade.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Among the climate marchers in New York City was Naomi Klein, the activist and best selling author known for incisive critiques of U.S. foreign policy and corporate power. In recent years she has turned much of her attention towards the climate crisis, joining the divestment movement and the fight against the Keystone XL pipeline. Her newest book is called This Changes Everything, Capitalism Versus the Climate and it argues that solving climate change will require that we challenge the entire logic and structure of the deregulated capitalist economy. We caught up with her in New York shortly after the massive climate demonstrations.

Welcome to Living on Earth!

KLEIN: Thank you. So good to be with you.

Anti-capitalist sentiments ran high at the People’s Climate March in New York City on September 21st, 2014, a day before the Flood Wall Street protest. (Photo: The City Project; Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: One of the things that's really fascinating with this book this is you present climate change in its historical context. It doesn't exist in a vacuum, it's part of this history of globalization and trade and development. So what is the connection between free-trade and global warming in your view?

KLEIN: Well, we know that the global economy has been expanding very, very rapidly, and it's been expanding on a very particular model, which is all about removing the barriers to investment and manufacturing. This is what allows corporations to set up shop in free-trade zones in China and move their goods around the world and so on, and it's a very, very profitable model. It's also very high carbon model, not just because of the transport, but also because - and I argue in the book - that that there is a connection between cheap labor and cheap energy, and cheap energy tends to be coal. Right? So if you are multinational and your only goal is to lower your production costs, and that's really been the story of our era, then it isn't just that you're to find the cheapest, most exploited labor force in the world. But in that relentless drive to push down costs, you are also going to see a race towards ever dirtier energy. So at the same time as industrialized countries in Europe and United States and Canada and elsewhere are actually lowering their emissions and cleaning up their industrial production, and wages were going up when production moved to countries like China, not only did wages go down, but emissions went up.

In her new book, This Changes Everything, Klein argues that globalization and free trade drove climate change. (Photo: naomiklein.org)

CURWOOD: So that means that if I buy an air conditioner that was made in China with cheap energy, that my emissions in the U.S. are low, but I just raised China's?

KLEIN: Yes, sometimes we pat ourselves on the back in countries like the U.S. and Europe that our emissions are not going up as quickly or even going down a little bit in certain years. The problem is our goods are overwhelmingly produced in other parts of the world now, and the emissions associated with those goods are accounted for entirely on the ledgers of the countries that do the production, so your air conditioner, your television, if it was made in China—then China is the one who's responsible for all those emissions. And then the weird thing is that the emissions for transporting that air conditioner and TV are not counted towards any country's emission. They're just not accounted for.

And so, I talk about how you had these two parallel processes of international negotiations that were going on at the same time - the climate negotiations and then on the other hand the trade negotiations. And the weird thing is one pretended the other wasn't happening. It's like these two conversations were just entirely parallel and not intersecting, so the rules that were locked in when trade agreements like NAFTA were signed put up barriers for governments that wanted to enact good green energy programs. So for instance I live in Toronto, which is in Ontario—my government actually passed a really ambitious green energy plan, and there's a requirement that if you want to benefit from the subsidies, you have to produce a certain amount of your solar panels and wind turbines in Ontario. It was successful: 31,000 manufacturing jobs were created, closed down auto plants opened up and were turned into solar production plants; in the green economy that everybody talks about. And then Japan and the European Union took Canada to the WTO and said that this violated our obligations because you're not allowed to favor local industry, and in fact, there have been several trade challenges like this: the U.S. has challenged China, has challenged India, for its subsidies it supports for renewable energy.

In the midst of Climate Week in New York City, Steve Curwood sat down with Naomi Klein to discuss her new book, This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. The Climate. (Photo: Emmett Fitzgerald)

KLEIN: And to me it's just extraordinary because here we are in this moment where we want every government in the world to be doing everything possible as fast as they can to roll out renewable energy, and you go to a Climate Summit and all these governments are pointing the finger at each other. "No, you're not doing enough. No, you’re not doing enough." And then another wing, a more powerful wing of these governments, are running to the World Trade Organization and trying to knock down each other's windmills.

CURWOOD: I take it the bottom line of your book here is, if we want to solve the climate crisis, we have to change economic system, huh?

KLEIN: We do, and I think it's deeper than that. I think we need to have a debate about what kind of values we want to govern our society and the issue of bad timing that I lay out in the book, is that this crisis hit us with a certain set of values, sort of hyper-individualism—Margaret Thatcher's theory is there is no such thing as society, this idea that all we are is consumers—these were the values that came to govern. They're not the values that have always governed. This was a shift and it was a political project by a relatively small group of people that really set out to change the hearts and minds and change the culture. And it works to a great extent, but not completely because we know we're more than that. You know, especially when crises hit we see other sides of ourselves, that we can and want to act collectively. And so I think there's been this way in which we've been trying to respond to the climate crisis without rocking the boat, rocking the economic boat. So we'll appeal to people as consumers: It's all about changing light bulbs, buy a hybrid, buy some carbon offsets. This is the model that has dominated for 20 years.

The Revolutionary Communist Party was just one of several anti-capitalist groups at the People’s Climate March. (Photo: Jean Gazis; Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So let me ask you this: so the environmental movement, which has been sounding the alarm about climate has been trying to work within this economic model. How's that been going?

KLEIN: Well it hasn't been going very well. In the 1960s and ’70s and really up until 1980 when the Superfund Act was passed in the states, it was about polluter pays, right? You've got a pollution problem; the polluter's responsible. We're not just going to pass a new law, we're going to try to get the polluters to pay for the cleanup. Then comes the ’90s and climate change and it's, well, "No, no, no, it's polluter plays. We'll sit down with the polluters and we'll convince them that this is in their best interest. And we'll form a partnership, and we'll show Walmart that they'll save money if they introduce energy efficiency”. And you know what, it does. It saves money for Walmart to become more energy-efficient.

The problem is, Walmart is a company that, as we all know, is driven by an ethos of relentless growth just as our economy is, and though they are more energy-efficient, their carbon emissions continue to rise because they expand so rapidly. So this model of just trying to cajole corporations to introducing voluntary measures plus some consumer responses, it doesn't add up, and the carbon record doesn't lie. And if we mean what we say, when we call this "the greatest crisis facing humanity" to quote the Secretary-General of the U.N. or a "weapon of mass destruction" to quote John Kerry, if we believe this and we should, then why would we leave this to the boom and bust cycles of the market? Wouldn't we try to take the wheel and respond as we do in the face of grave threats?

A crowd of approximately 3,000 people carried signs and banners at the Flood Wall Street event on Monday September 22nd, 2014. (Photo: Stephen Melkisethian; Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: What's wrong with market-based mechanisms to deal with the carbon crisis, say something like cap-and-trade?

KLEIN: Well, we've been trying to deal with it this way, and I think, you know, that some of these mechanisms can work for smaller problems. The problem is that carbon is at the center of our economy. It's what our economies are built on. They're built on fossil fuels. So the changes required are just simply too great, and the market can get us partway there, but it can't get us all the way there. So it also requires some serious regulation. Europe has the largest carbon market in the world, and what we've seen is it's subject to all these problems: the housing market, they created a bubble, the price of carbon collapsed. It was also a magnet for fraud.

CURWOOD: So you say America lucked out not having Congress pass a cap-and-trade program.

KLEIN: Well, the cap-and-trade law was very much a product of this “polluter plays” model of environmental regulation. It was based on the logic that we aren't going to get anything done unless we can get the polluters on side. So, the model, and it was pioneered by the Environmental Defense Fund, was to bring some of the biggest carbon polluters in the country: big oil companies like BP and Chevron, Duke Energy, to sit around the table with a few environmental groups—there were many more corporations than there were environmental groups—and to hammer out an agreement. Well, imagine if we tried to do the same thing with the banks. What kind of agreement do you think you'd come up with? I think we kind of know. That's exactly what we've had. And so they came up with an agreement that really gave them a free pass that passed the cost to consumers. It also was a system that would allow coal companies to keep emitting so long as they offset those emissions by protecting a forest somewhere else or funding solar energy in another country, and that also takes away from the real energy towards climate action.

Protestors who ‘flooded’ Wall Street drew a direct connection between capitalism and “climate chaos.” (Photo: Susan Melkisethian; Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Like if you look at who came out to that climate march in New York—it was communities where kids have asthma, and they are already dealing with the real impacts of this toxic economic model. And so once you set up this carbon market offset system, it's called win-win but it's actually lose-lose because the people whose kids have asthma are still dealing with that. They don't get the refineries shut down and replaced with clean energy, and then often people on the other side of the world whose land is deemed a carbon an offset also lose because they often lose access to their land and their forest becomes a kind of tree museum that is all just about capturing carbon. And they're not able to engage in subsistence logging, in subsistence agriculture.

CURWOOD: So is your book criticizing capitalism or is it more simply about big oil, whether it's capitalist or not? I mean, Russia has gas, China has a huge petrol company, Statoil in Norway. There are other big private companies, but there are big public ones.

KLEIN: Well the book is about a clash between a logic: this logic of short-term growth, short-term profits above all else, and what we need to do to solve this climate crisis which is, I think, respond strategically, and that means that we need to contract certain parts of our economy and expand other parts of our economy. And whether it's a state-owned company at this point or a privately held company—they're all traded on stock exchanges, and they're all in the grips of the same logic. So, yeah, Statoil, is a publicly traded company even though it is still state-owned, and despite the fact that Norwegians are very concerned about climate change and have tried to pressure Statoil to pull out of the Alberta tar sands and to back away from Arctic drilling, they found that it's very difficult to get the company to be responsive. But still, I do think that having some of these energy companies in public hands, there's more of a chance of changing them. I think the Norweigans have more of a chance ultimately of changing a company like Statoil and capturing the enormous profits from fossil feels and using those profits to get us off this path. I mean, this is the issue: We need to return to a “polluter pays” model because we're told all the time that our government's are broke. We can't accept that as a response to climate change, and that means we need to go to where the money is, and luckily, fossil fuel companies are the wealthiest industries in the world. No company has ever made more than Exxon Mobil. And we need to find ways to capture more of those profits to pay for this transition.

Naomi Klein (Photo: Nicolas Haeringer; Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: You write at one point in your book, and I'm quoting you here, "The resources for this just transition must ultimately come from the state, collected from the profits of the fossil fuel companies in the brief window left while they're still profitable".

KLEIN: I mean, that seems logical enough to me. It's a principle that was applied to the tobacco companies, once tobacco profits were deemed to be illegitimate, in the sense that the science was in and documents were revealed that showed that the tobacco companies understood the link between smoking and cancer and were denying it. The same sort of dynamic is emerging with the fossil fuel companies and that's why you have this very fast-growing fossil fuel divestment movement, very much driven by young people and faith communities who are saying, “these are immoral profits. It's immoral to profit from a business model that knowingly is destabilizing our home, our life-support systems”.

So I think once we recognize that, then we need to capture more of them, and we need to use them to get off those sources of energy because it's an expensive process, and nobody else is offering the money. It's not just the fossil fuel companies that need to finance this, but it's impossible to imagine us responding to this crisis in the way that we must without having that, what I call in the book "the battle of world views", right? Because so many of the certain, reasonable, rational things that we need to do in the face of this crisis have become taboo. "You don't plan an economy, what you talking about?" Increasing taxes, you're not allowed to talk about that, taxation and regulation, all of these. This is the legacy of the ideological project that was launched in the 1980s and this is why climate change had the worst possible timing, it landed on our laps when all of the tools that we needed to respond to this crisis were being taken out of our hands. We need to take them back.

Hundreds of people helped carry a three-hundred-foot-long banner that read, “Capitalism = Climate Chaos – Flood Wall Street” at the Flood Wall Street event Monday. The banner had also made an appearance a day earlier, at the People’s Climate March. (Photo: A Jones; Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So how do we do this? And how long do we have to do this, I mean, both from a climate perspective and an economic one?

KLEIN: Well, look, I think the good news is that more and more people realize that we need a different kind of economic system, whether or not there is a climate crisis. There is an inequality crisis; it's extremely deep in the United States. And the level of dissatisfaction with deregulated capitalism is higher than it's been since the 1930s. People want a better system, and in fact they know that if we were to respond decisively to this challenge, the investments in the public sphere, the investments in renewable energy, would create many, many more jobs than the fossil fuel economy is offering now. And so we don't have a lot of time; I mean, we're on a deadline. I happen to think that deadlines can be helpful, but I think we're on a deadline for a lot of reasons. I think the inequality crisis is just as pressing as the climate crisis, and if we can bring these two discussions together, then I think we can start moving very quickly.

CURWOOD: In your book you say activism is rising because what you call "extractivism" has wound up here in America. It's not just overseas, in colonies, but it's happening in communities that are facing fracking and that sort of thing. How do you think that's changing the political discussion?

KLEIN: Well, the truth is our economy has always required sacrifice zones, sacrificial people and sacrificial places. This is the story of the founding of this country, whether the sacrificed people were slaves or whether the sacrificed places were the coal mining communities and the coal miners. So it's not that extractivism and the impacts of extractivism are new, it's that everybody is in the sacrifice zone now, and it's building alliances between different constituencies that had previously been separated.

CURWOOD: So in your book, you hold up grassroots political protest as really just about the only thing that's going to get us from where we are now to a climate-friendly future. What did if feel like to march here in New York?

KLEIN: Well, it felt great. I mean, the People's Climate March was an extraordinary experience. It wasn't just that it was huge, and it was - I've never participated in a larger demonstration - it was that it was completely unlike any climate event that I have been a part of. I was in Copenhagen in 2009, and I was at the Forward on Climate March in front of the White House protesting the Keystone XL pipeline. This felt different because it looked and felt like New York City. It was not an NGO organized event, although NGOs were involved. It really was a people's climate march, so the indigenous people who were at the front of the march, a lot of them came from Alberta, Canada, who are living downstream from the tar sands are dealing with very high cancer rates, are dealing with the fact that the animals that they've always depended on are getting sick.

Author Naomi Klein with our host Steve Curwood and producer Emmett FitzGerald in New York for the climate rallies. (Photo: Julia Prosser)

And then you have people from New York State who are trying to protect a moratorium on fracking and are worried about their water supplies. So I think that what's so significant about this wave of organizing, is that it has such a powerful sense of urgency, that it is about children's health. It is about people losing their homes to Superstorm Sandy. It's about the connection between this global crisis and how it's playing out locally, whether with the effects of climate change or the direct impacts of fossil feel extraction or combustion or transportation. I personally don't believe that grassroots resistance is going to get us to where we need to go, in that we need national bold policies; we need international treaties. You know, it's not just going to be the resistance at the community level that will get us there, but right now these are the signs of hope. It's the people who are doing what the politicians won't do, which is say to the fossil fuel companies, "You have to keep this carbon in the ground".

CURWOOD: Naomi Klein's new book is called "This Changes Everything: Capitalism Versus the Climate". Thanks for taking the time today.

KLEIN: Thank you. It was a great conversation.

[MUSIC FROM THE PEOPLE’S CLIMATE MARCH]

Links

This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. The Climate by Naomi Klein

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth