September 26, 2014

Air Date: September 26, 2014

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Record March for Climate Action

/ Helen Palmer, Emmett FitzGerald, Naomi ArenbergView the page for this story

At the start of 2014’s Climate Week in New York City, Living on Earth’s Emmett FitzGerald, Helen Palmer and Naomi Arenberg were on the scene as 400,000 people of all types and ages marched through the streets demanding global cooperative action on global warming in advance of a UN climate summit. The team shares the sounds and scenes with host Steve Curwood. (11:45)

U.N. Climate Summit Pledges Global Commitment and Action

View the page for this story

On September 23rd, over 125 heads of state, as well as officials, CEOs, and NGOs gathered at the United Nation’s Climate Summit to reaffirm their commitment to curtailing climate change and their global plans for action. Jennifer Morgan, Director of the Climate and Energy Program with the World Resources Institute, discusses the Summit’s outcomes with host Steve Curwood. (10:45)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s trip beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra tells host Steve Curwood about the shrinking of the western snowpack, the spreading of Lyme disease, and the building of a dam despite the presence of a tiny, endangered fish. (03:40)

BirdNote® A River of Raptors Over Veracruz

/ Michael SteinView the page for this story

In September, migrating hawks, turkey vultures, and kestrels flood the skies above Veracruz State in eastern Mexico. Michael Stein shares an excerpt from Scott Weidensaul’s book Living on the Wind: Across the Hemisphere with Migratory Birds, as Stein witnesses hundreds of thousands of raptors on the wing. (02:05)

Capitalism vs. The Climate

View the page for this story

Naomi Klein, a best-selling author, social critic and climate activist, attended the public demonstrations of Climate Week 2014 events in New York. She sits down with host Steve Curwood to discuss her new book, This Changes Everything: Capitalism versus the Climate, which argues that global warming is largely driven by globalization and unregulated free trade. (19:20)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Jennifer Morgan, Naomi Klein

REPORTER: Peter Dykstra, Helen Palmer, Emmett FitzGerald, Naomi Arenberg, Michael Stein

[THEME]

From Public Radio International - this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. From across North America, a record crowd of more than 400,000 came to New York City to march for action global warming before it’s too late.

STEIN: This feels like it's a real transition moment. And as the old system grinds down, there is a new people’s movement, which is rising up from the bottom, it’s everyone united for this agenda of people, planet and peace over profit.

CURWOOD: And as the people marched, more than a hundred heads of state and government, business leaders and advocates came to the UN for a summit on the climate.

MORGAN: Both leaders and many others actually gave a very clear message that they do not see a choice between tackling climate change and growing their economy. They actually know that they have to pursue a different economic pathway and they are up for figuring that out.

CURWOOD: Climate week and more, on Living on Earth, stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies – innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live.

Record March for Climate Action

Climate leaders at the People’s Climate March on September 21, 2014. Pictured (from right): Ségolène Royal, Minister for Environment, Sustainable Development and Energy of France; Ban Ki-Moon, UN Secretary-General; Bill de Blasio, Mayor of New York City; Al Gore, former Vice President of the United States and Nobel Laureate; UN Messenger of Peace Jane Goodall. (Photo: United Nations Photo; Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

[CHANTING: WHEN THE AIR WE BREATHE IS UNDER ATTACK – WHAT DO WE DO? STAND UP FIGHT BACK! WHAT DO WE DO? STAND UP FIGHT BACK!]

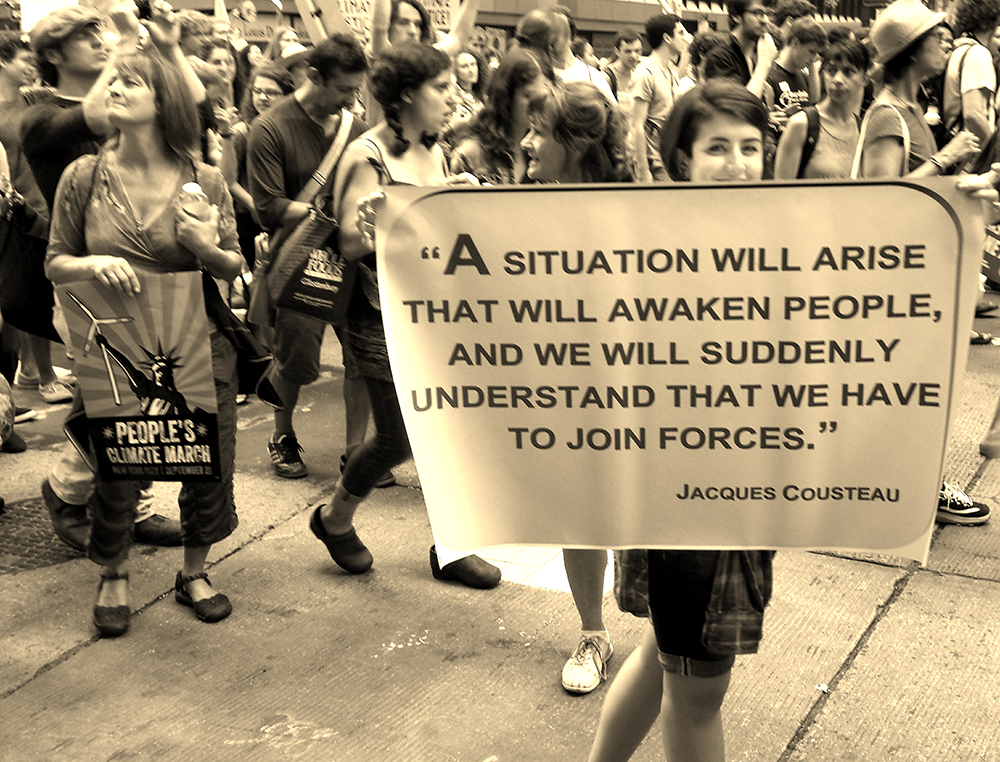

CURWOOD: It was Climate week in New York, and there was a massive call for action on global warming. More than 400,000 folks converged on Manhattan for the People’s Climate March, along with a special summit session at the UN and carbon profit protests along Wall Street. The Living on Earth team was there -- including Naomi Arenberg. So, Naomi, you got up before dawn to board one of a fleet of buses from Cape Cod, Massachusetts. Who was there?

United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon (in blue cap) hosted the UN Climate Summit at that UN headquarters on September 23rd, 2014 in New York. (Photo: United Nations Photo; Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

ARENBERG: Steve, lots of people were already waiting in the dark when I arrived. In fact the parking lot where we left our cars was just about full. What really surprised me was all the young faces in the crowd, teenagers, the ones I’d expect to be asleep at that hour. And four of them turned up on my bus. They snoozed along the way, but I talked to their Environmental Studies teacher.

DR. PETE: The students call me “Dr. Pete.” I teach at Sturgis Charter School, although this is a personal trip with students that are traveling down to what I hope to be a turning point in the political kick-in-the-butt that’s needed for change.

Marchers demand an end to fossil fuel consumption for energy. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

ARENBERG: So, Steve, the march started officially at Columbus Circle – that’s, what, 59th Street? My bus driver let us off at 89th Street, and even that far uptown the sidewalks were crammed with people, all scurrying toward Central Park and the march. In the midst of this sea of motion, one man was standing still and serenading the rest of us.

[ACCORDION AND SINGING: WE SHALL NOT BE MOVED.]

PAUL: My name is Paul. I’m an activist musician from Brooklyn, and I’m so happy to be here today, fighting for our planet, and for ourselves, our children, and our grandchildren. And thousands, literally thousands, of people are getting off buses here—it’s the most amazing thing. I’m so excited!

A woman in a mermaid costume holds a sign, “Mermaids oppose offshore drilling.” (Photo: Joshua Rifkin)

ARENBERG: And those thousands of people? They and I waited and waited and waited on Central Park West for over an hour before the crowd even budged. It took three hours for us to get to Columbus Circle! The street was packed, like the subway at rush hour. But folks stayed calm. There was a huge police presence, both officers and community police in blue polo shirts, and they were calm. Once in awhile I’d overhear someone say, and I love this, “At least people showed up.”

CURWOOD: Another Living on Earth team member, Helen Palmer, was there. Helen, where were you?

Marchers understand that the climate crisis is everyone’s problem and therefore everyone must band together, cooperate and be part of the solution. (Photo: Joshua Rifkin)

PALMER: Well, I was hanging out at 46th St and 6th Ave, and it was remarkable, Steve, and joyful and very musical. It was almost like a carnival parade.

[BALKAN JAZZ BAND PLAYING]

PALMER: There was a Balkan jazz band. There were singers and many familiar chants repurposed.

[CHANTING: “HEY HEY, HO HO, FOSSIL FUELS HAVE GOT TO GO!”]

PALMER: The organizers wanted a “big tent” because what’s happening to the climate affects everybody. More than 50,000 students marched. Over 1500 different organizations were there – there was a strong labor contingent, including many from the Domestic Workers Alliance, brandishing brooms and mops. There were anti-nuclear campaigners, Veterans for Peace, many different faith groups, and Native Americans.

Young marchers petition for climate justice for people and animals alike. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

[NATIVE AMERICAN CHANTING WITH DRUMS]

ANSTER: My name is Britney Anster, I represent the Haliwa-Saponi nation of Hollister North Carolina. It’s important because we are nature – we are the air, the earth, not just indigenous people, but all people. We share this communal earth and we’re here fighting for climate justice, just not for us, but for all people– especially for future generations.

PALMER: Native Americans and Canadian First Nations were leading the march along with some of the other communities most affected by global warming - island nations, and people on the frontlines who’ve already experienced weather extremes: people like Kathy Sykes from Jackson Mississippi.

Generations young and old walk together for action in the People’s Climate March. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

SYKES: I’m here because we as a people have to come together to do something about climate change –Mississippi has seen the brunt of it with Hurricane Katrina. We still have not recovered. We’ve had a bit oil spill on the Gulf Coast. It is terrible. So we’re here fighting, trying to do whatever we can to draw attention to the need to stop climate change and save our world.

[DRUMS AND CHANTING]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth’s Emmett Fitzgerald was there. Now, Emmett, what did you see along the lines of climate change as an environmental justice issue?

Peoples of all cultures walked in solidarity. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

FITZGERALD: Yeah, I was really curious going into the march where environmental justice would fit in. You know, mainstream environmentalism in the U.S. has tended to be such a white, middle-class movement, and that element was certainly there in New York—people from the big environmental groups like the NRDC and EDF. But many of the groups at the People’s Climate March were local grassroots organizations, and they brough lots of people of color. The whole thing just felt more egalitarian than environmental demonstrations I’ve been to in the past.

It was interesting to me that there weren’t any speeches. You know, you had all these celebrities and famous politicians, people like former Vice-President Al Gore and U.N. Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon, but they didn’t get any special attention. They were just marching in the crowd like everyone else. At one point I realized I was standing right next to Jill Stein, the former Green Party Presidential Candidate.

Indigenous peoples marched on Sunday for their rights to a healthy climate for the sake of the Earth and future generations. (Photo: Joshua Rifkin)

STEIN: This feels like it's a real transition moment. And as the old system, kind of, grinds down, there is a new people’s movement, which is rising up from the bottom. It’s everyone uniting on this united agenda for people, planet and peace over profit and that’s what I find so exciting—is for us to be here and to start discovering our strength at the moment when we badly need it.

[CROWD NOISE]

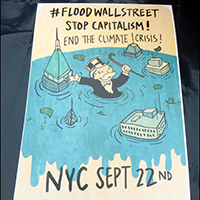

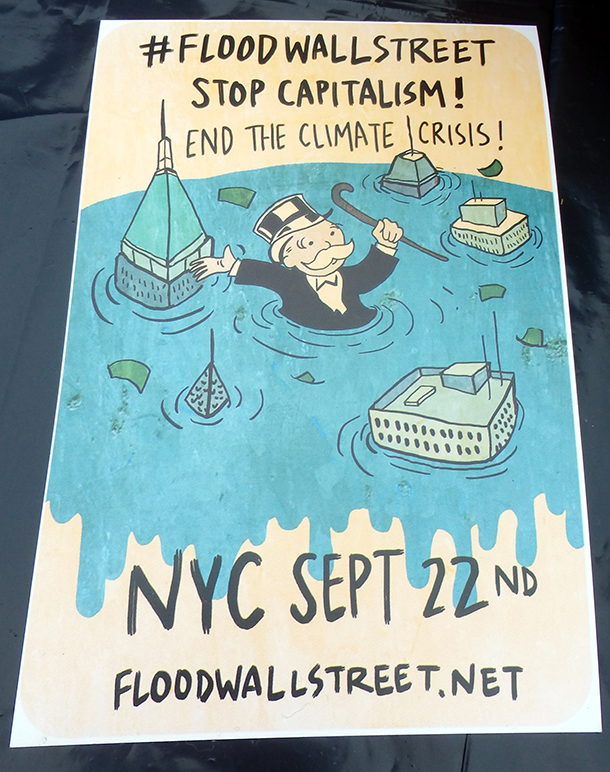

CURWOOD: And Emmett, you stuck around on Monday for this protest called Flood Wall Street.

Groups like the National Black Environmental Justice Network came out to the People’s Climate March, chanting about climate action. (Photo: Joshua Rifkin)

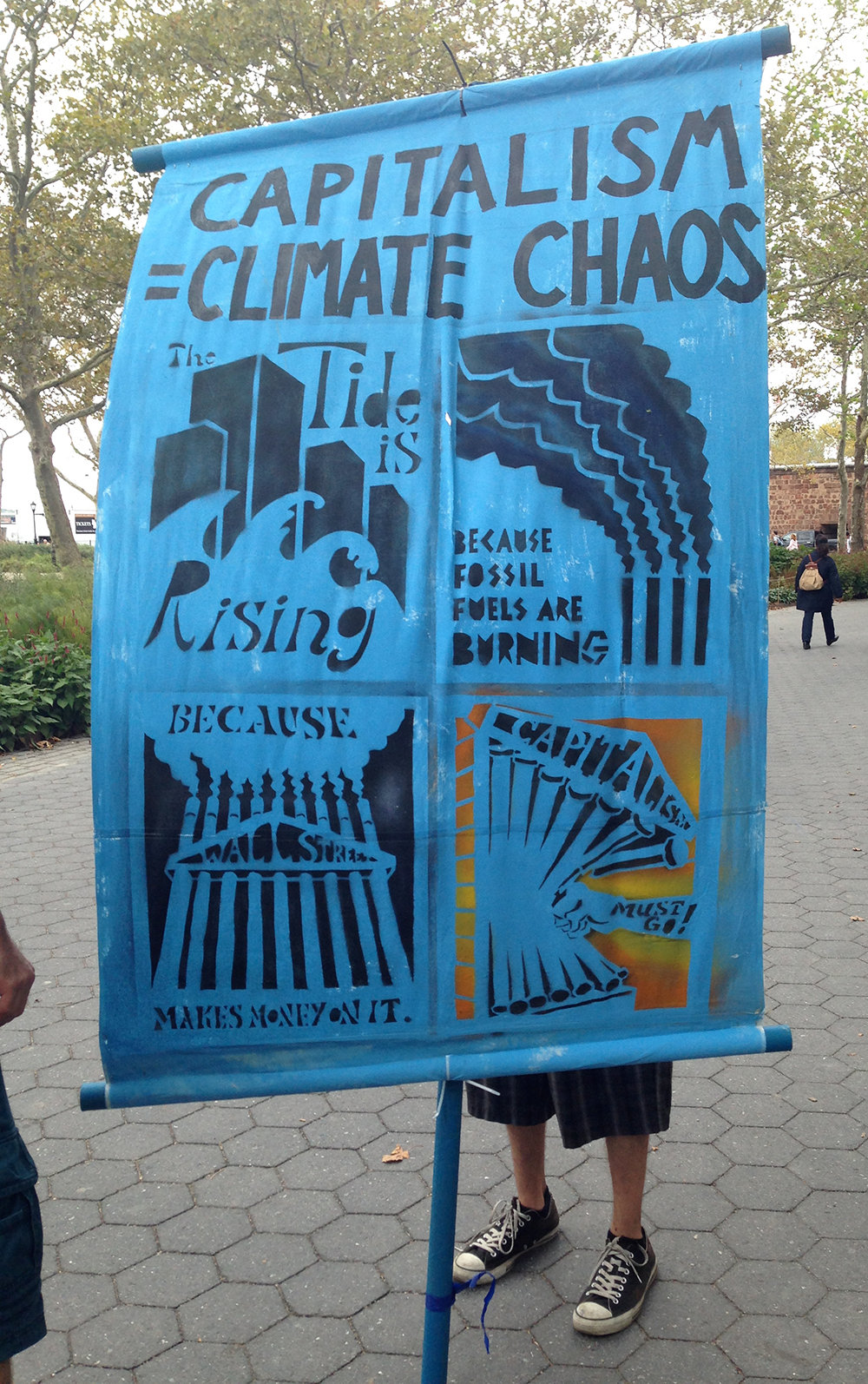

FITZGERALD: Yeah, Flood Wall Street was a demonstration called for by the Climate Justice Alliance, a coalition of Environmental Justice groups, and the plan was to stage a sit-in right in the heart of Wall Street.The organizers wanted to link the climate movement with the economic and racial justice movements, and really put the responsibility for climate change squarely on the capitalist economic system itself.

So, on Monday morning, a few thousand people, all wearing blue shirts, gathered in Battery Park. They got a quick Occupy Wall Street-style primer on civil disobedience, and then one of the organizers used the “people’s mic” technique from Occupy Wall Street to teach everyone a song.

Some worried about the climate crisis’ effect on pollinators like bees and their dwindling numbers. (Photo: Joshua Rifkin)

[MAN SHOUTING: MIC CHECK! CROWD: MIC CHECK! MAN: I’M GOING TO TEACH YOU A SONG. CROWD: I’M GOING TO TEACH YOU A SONG]

FITZGERALD: It took a little while, Steve, but they got the hang of it eventually.

Jill Stein, Green Party nominee for the 2012 Presidential election, marched in New York on September 21st. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

[CROWD SINGING: THE PEOPLE GOING TO RISE LIKE THE WATER, GOING TO CALM THIS CRISIS DOWN. I HEAR THE VOICE OF MY GREAT GRANDDAUGHTER, SAYING “SHUT DOWN WALL STREET NOW!”]

FITZGERALD: Eventually the blue flood of people poured into the streets. Police blocked the protesters trying to enter Wall Street proper, but they streamed around the iconic bronze bull on Broadway, effectively blocking all traffic on one of the financial district’s major arteries. You know, Steve, it was really hard to tell how many people were in the crowd at that point, well over a thousand I would guess, and the mood was hopeful.

Impoverished and indigenous groups feel the effects of climate racism and are disproportionately affected by it. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

[CHANTING: WE ARE UNSTOPPABLE ANOTHER WORLD IS POSSIBLE.]

FITZGERALD: I don’t know if the organizers were expecting to get arrested right away, but the police had clearly been instructed to let them do their thing. The demonstration carried on throughout the afternoon. Tourists stopped to take pictures, bankers in suits tried to push their way through the crowd to get to work. But at 6:45, the cops decided they had had enough and told the protesters to go home. At that point, a group of people sat down, and the police moved in and began cuffing them. In the end, 104 protestors got arrested, including one person dressed like a polar bear.

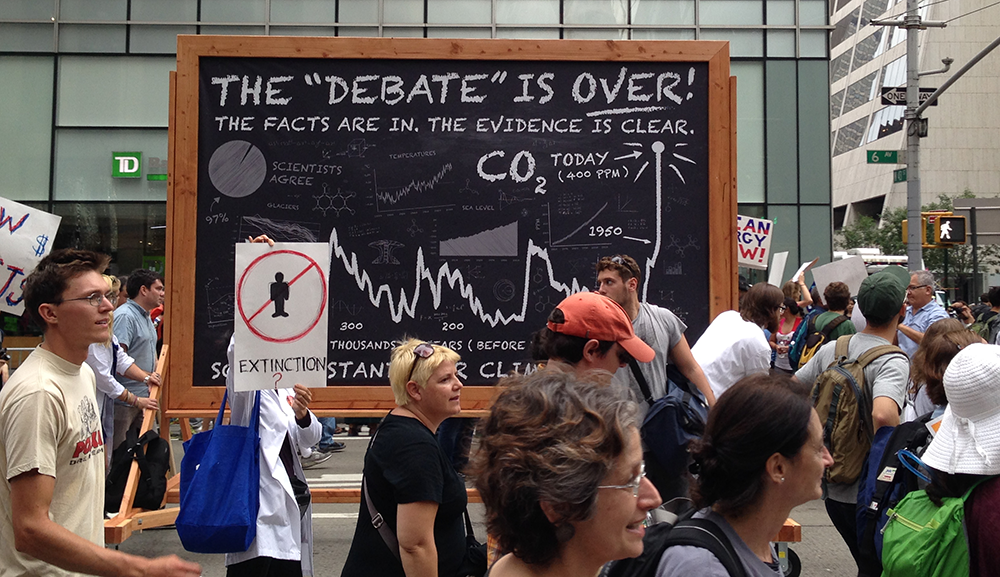

Marchers addressed climate deniers with signs reading, “Leave science to the scientists.” (Photo: Joshua Rifkin)

CURWOOD: So I want to ask all of you – this is the biggest public demonstration of people’s concern about the urgency to act on climate change that there’s been to date. What did you take away from this march? Emmett?

FITZGERALD: Yeah, I mean, a lot has been made of the size of the march and I think that was really impressive, but maybe more important was the messages that people were sending. This felt more pressing then anything I’ve been to before because so many people were talking about how climate change and the fossil fuel industry are impacting their day-to-day lives. I think human stories like that are always more powerful then abstract policy recommendations, and it was cool to see those voices front and center. And you know, Steve, although there was clearly a lot of anger about climate change in New York, there was also a palpable sense of positivity and hope that this kind of movement could lead to real change.

Climate change is science, not an option. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

CURWOOD: Now, Helen, what about you?

PALMER: Well, I was struck by how good-natured the whole thing was. and how witty some of the placards were. There were signs like “There is no Planet B” and “I’m sure the dinosaurs thought they had time too!” Then I thought the costumes were really imaginative– there were people dressed as trees, and one woman in a wheelchair decked out as a mermaid with a sign “Mermaids against climate change” and there were massive globes being propelled along by bicycle power.

Marchers held empowering banners expressing optimism for curbing climate change. (Photo: Joshua Rifkin)

PALMER: And you know, Steve, as a beekeeper, I was pleased to see quite a few folks wearing protective bee-suits, pointing out that these weather extremes aren’t too good for honey-bees either! One of my favorite moments – there was a group of biology and ecology professors wearing wings and stripy black and yellow tops who called themselves the “Bee Block” and they were chanting about insects.

[CHANTING: “WE ARE THE INSECTS – THE MIGHTY, MIGHTY INSECTS – THE GLOBAL WARMING INSECTS –THE DISAPPEARING INSECTS—THE PLANET SAVING INSECTS”]

People of all ages came to New York City for the climate march on Sunday. (Photo: Joshua Rifkin)

CURWOOD: Well, Helen, we can always count on you to give us the buzz!

PALMER: Oh!

CURWOOD: And Naomi, what did you take back on the bus?

ARENBERG: Well, Steve, I’m with Helen. What’s fixed in my memory is the whole sense of the event—friendly, calm, courteous and the true openness of each group to the other. Also, that focus on young people: Parents asking for a healthy environment for their children. Children speaking for themselves, carrying their own handmade signs. So my bus was waiting on 11th Avenue at 26th Street to take home 50 weary travelers, and there was a lot of conversation about the march and how important those young people had been.

Many blame a corrupt capitalist system for exploiting natural resources, leading to our climate crisis. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

MAN: I think the most inspirational part to me today was, everyone keeps saying, “Where’s the young people?” The young people were here today in droves. They came from Wisconsin. They came from Los Angeles. They came from North Carolina. It was just really inspirational.

ARENBERG: Three high school students were squished together into the two seats right in front of me.

GIRL: I had so much fun today. Yeah, it was my first protest, also my first time being in New York. I’m 17. I don’t know, it was a really good experience. There were so many people out there.

Covered in blue, thousands of protestors “flooded” Wall Street. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

BOY: I mean, it was my first protest as well, so I wasn’t very good at chanting at first, but I got pretty good at it.

GIRL: Yeah, it was pretty fun. I love chanting. Chanting is a good thing.

[LAUGHS]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth’s Naomi Arenberg, Helen Palmer and Emmett Fitzgerald, who were all in New York City for the climate demonstrations.

[SINGING: THE PEOPLE GOING TO RISE LIKE THE WATER, GOING TO CALM THIS CRISIS DOWN. I HEAR THE VOICES OF MY GREAT GRANDDAUGHTER, SAYING “SHUT DOWN WALL STREET NOW!”]

CURWOOD: And coming up: an assessment of what went down at the U.N. climate summit. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth – stay tuned.

Related links:

- Pictures, videos and tweets from The People’s Climate March: 400,000 marched in New York; 700,000 marched worldwide—the largest climate march to date!

- Read an analysis of the U.N. Climate Summit, which followed the People’s Climate March

- Flood Wall Street: Hundreds of people protested Wall Street institutions and their exploitation of natural resources leading to our climate crisis.

- Photos from Flood Wall Street on September 22nd, 2014

U.N. Climate Summit Pledges Global Commitment and Action

More than 100 world leaders, government officials and heads of state gathered at the United Nations headquarters in New York on September 23rd, 2014 for the UN Climate Summit to reaffirm their dedication to climate action and gearing up for climate negotiations in Paris next year. (Photo: Palazzo Chigi; Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Two days after the biggest public demonstration in history to call for climate protection, more than 125 heads of state and government gathered in New York for the opening of the General Assembly of the United Nations. The U.N. set aside September 23rd for an informal climate summit and President Obama set the tone:

[OBAMA: Mr. President, Mr. Secretary General, fellow leaders: for all the immediate challenges that we gather to address this week -- terrorism, instability, inequality, disease; there’s one issue that will define the contours of this century more dramatically than any other, and that is the urgent and growing threat of a changing climate.]

CURWOOD: The President and other world leaders pledged action ahead of a formal climate treaty session in Paris next year. Long time global warming negotiator Jennifer Morgan is the Director of the Climate and Energy Program for the World Resources Institute and she joins us now from New York. Welcome back to Living on Earth!

MORGAN: Thanks! Good to be here.

President Barack Obama speaks at the United Nations Climate Summit in New York City on September 23rd, 2014. (Photo: U.S. Department of State; Flickr Public Domain)

CURWOOD: So tell me about the kinds of people and groups who attended this U.N. summit.

MORGAN: It was a broad range of people. There was a strong business community, and within the business community you had insurers, private banks, oil and gas companies, you had paper and pulp companies, so you had a private sector part of the summit. You also, of course, had lots of government delegations that were there with their leaders, and you had civil society representation which also was a broad spectrum—from faith to environment NGOs, development NGOs. It's just an everyone problem and therefore it needs to be an everyone solution.

CURWOOD: So during the summit, leaders from those countries and those sectors stated goals and commitments towards addressing climate change. Give me a highlight of the kinds of pledges that were made and reaffirmed.

Heads of State and Government participate in the UN Summit on climate in New York on September 23rd, 2014. During the summit, Italian Prime Minister and President of the European Council, Matteo Renzi, chairs the thematic session on "Cities". (Photo: Palazzo Chigi; Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

MORGAN: So I think some of the really interesting highlights were things from the finance sector. You had the Swedish pension fund agree to commit to completely decarbonize their assets, which would shift $100 billion next year. You had insurers come in and commit also to be decarbonizing their investments moving forward and scaling that up if there's a global agreement next year. You had mayors there, committing to reducing their emissions in their cities more, countries coming forward and committing to restore degraded lands, to build forests. And then you had, kind of more political commitments from the heads of state, about delivering the agreement in Paris next year, about making sure their country puts forward its offer for what they’ll do in the future, and a few of them put real money on the table for this Green Climate Fund to support poor, developing countries.

CURWOOD: What about the Green Climate Fund, the pledge back in Copenhagen that eventually by 2020 to be what, $100 billion a year, that would go to support less-developed countries to address the climate? What emerged at this summit to support that pledge?

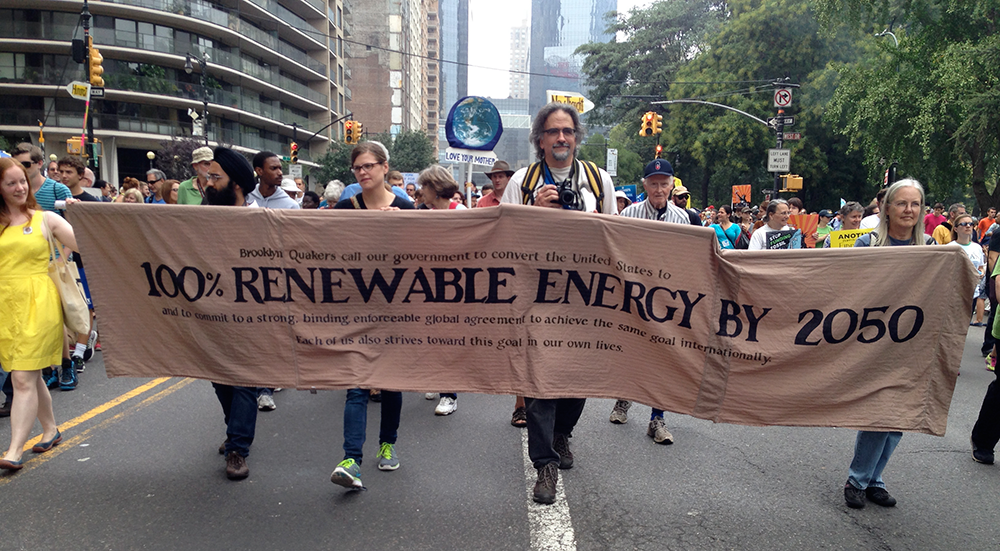

Agreeing with the marchers, many country leaders expressed a desire to run on 100% renewable energy by 2050. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

MORGAN: Well, at this the summit you had some pledges coming in: Germany reconfirmed its billion dollars. France put a new billion dollars on the table. You had, actually, countries like Mexico pledge, which was very important from a more developing country, and a number of countries said that they would deliver their pledges by November, which is the deadline. So there was a down payment of about $2.3 billion. I think there is a goal to get that to $10 billion by the end of this year, but clearly there's a lot more that needs to be done on leveraging and capitalizing that Green Climate Fund.

CURWOOD: What about the United States? Where is the U.S. government on these pledges?

MORGAN: Well, my understanding is that they are working hard right now to get their pledge together, and that they will meet that November deadline, so wait and see.

CURWOOD: I'm hearing that the U.S. is looking to the private sector as well as public money to help meet this pledge. What do you hear along these lines?

MORGAN: Yes, I think that's true. I think that there is a real recognition and these pension fund commitments that I mentioned go along these lines, that we not only need the public funding, but we also need to shift the trillions of private funding into infrastructure, into energy, and so I think there's a mix—you think about it almost like an ecosystem of different financial approaches where you need everything to be shifting with public leveraging much greater private finance.

CURWOOD: What about divestment? There was much made of some foundations saying that they're going to divest their portfolios of fossil fuel investments. How big a deal was this at the Summit?

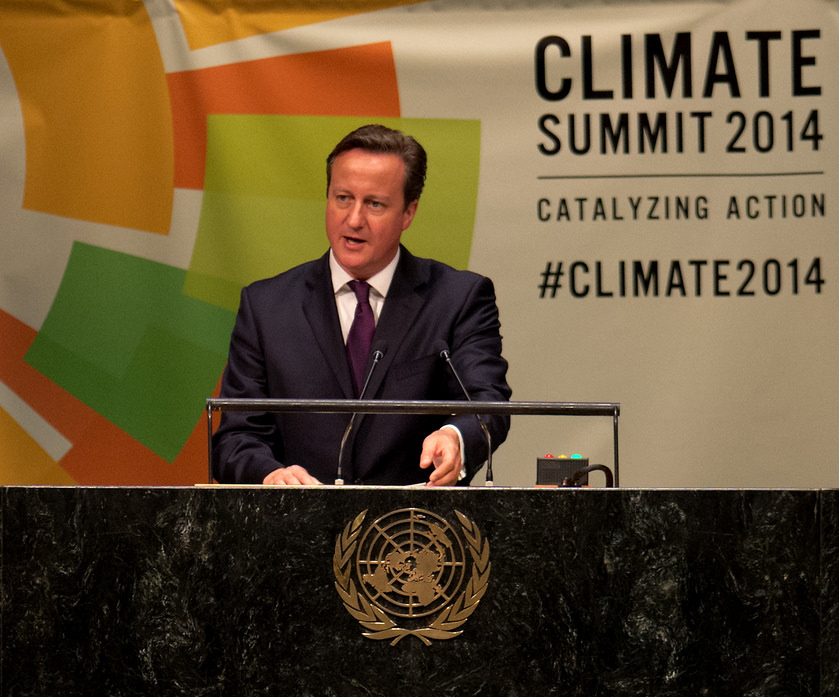

David Cameron gives a speech on climate change at the United Nations General Assembly. (Photo: Arron Hoare/Number 10; Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Well, the Rockefeller Brothers fund came out and made a major announcement that they are shifting their portfolio out of fossil fuel into clean [energy]. I think that sends a very big signal because of the background of that family in the oil industry. So I think you see those types of big announcements coupled with announcements from pension funds and insurance companies that are shifting into the clean solutions that are needed. It's a very clear signal into that finance sector.

CURWOOD: Now, half of world emissions now are between U.S. and China. Specifically, what did the U.S. say? What did China say at this summit?

MORGAN: Well, there were very powerful speeches by both the U.S. and Chinese leader, one after the other. It was like a one-two punch. President Obama committed himself personally to work together and said that the U.S. understands its responsibility. It is acting domestically, but it needs a global approach with all countries coming together or else it just doesn't work - nobody gets left off the hook. And he pledged to put their number on the table early next year and also to support developing countries with more resiliency or helping them adapt.

The Chinese leader also recognizes the Chinese responsibility to act, and his big announcement was that they will work to peak their CO2 emissions as soon as possible. China is the world's largest polluter right now, so when they peak, at what level they peak, is really very fundamental. And finally, I think both leaders and many others actually gave a very clear message that they do not see a choice between tackling climate change and growing their economy. They actually know that they have to pursue a different economic pathway and they are up for figuring that out.

Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon (left) and Sultan Ahmed Al Jaber, Climate Change Envoy of the United Arab Emirates (UAE), hold up signs that read, "I'm for Climate Action", in English and Arabic, at their joint press conference in Abu Dhabi. The UAE hosted on 4-5 May the Abu Dhabi Ascent, a high-level meeting to generate momentum for the 23 September Climate Summit being convened by the UN Secretary-General. (Photo: United Nations Photo; Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Let's talk about some of the different declarations that were made. Tell me about the New York Declaration on Forests that came out of this.

MORGAN: So the New York Declaration on Forests is a declaration that includes many countries and different players. It's aimed at ending deforestation by 2030, and really trying to drive that goal home.

CURWOOD: And what's the goal of the We Mean Business Coalition?

MORGAN: The We Mean Business Coalition is an interesting new, large group of companies and organizations that work with companies. They released a statement noting their support for a phase-out agreement of greenhouse gas emissions by mid-century. They want a clear signal from government. They support pricing carbon. I think it's a real attempt to try and show that there's support in business for action on climate.

Jennifer Morgan is the Director of the Climate and Energy Program with the World Resources Institute and was present during the People’s Climate March and UN Climate Summit 2014 in New York. (Photo: Courtesy of the World Resources Institute)

CURWOOD: In efforts to reduce the global carbon footprint, there are a number of proposals for greener transportation. What kinds of projects are being discussed?

MORGAN: Well, you know, transportation, I think, often gets forgotten, but it's really fundamental in this debate. We know there were a number of transportation initiatives for global alliances launched—initiatives to scale up sustainable mass public transport solutions. The International Union of Railways launched a low-carbon sustainable rail transport challenge and they're looking to reduce emissions by 75 percent by 2050. You had 110 public transport groups make commitments leading up to the summit and are really looking to double the market share of public transport around the world by 2025. This brings mega-savings in carbon: one gigaton of carbon by 2050, and it really puts transport on the map as far as a solution to climate change.

CURWOOD: And what's it worth to people and the economy to have this kind of shift?

MORGAN: Well, it actually could save governments, companies and individuals $70 trillion. I mean it's just a mega-winner for people getting to work, government saving money and cities to be much more clean, lower air pollution as well.

CURWOOD: So even though what's on the table is really sort of an amped up voluntary approach to restricting carbon, this is progress from your perspective?

MORGAN: Well, the New York summit was really not about the negotiations, it was about building momentum for the binding international agreement that is being negotiated in parallel, so it was meant to bring leaders back into the debate, to put it on their table. They have to engage with this issue, and so from that perspective, I think it really succeeded.

CURWOOD: What, if any, were the big surprises for you about what's going on during climate week there in New York in the U.N.?

MORGAN: Well, I think the biggest surprise was the size of the march. I think the organizers were hopeful that they could get 100,000 or so out and getting 400,000 people on the streets in New York and, you know, up to 700,000 around the world I think was just a big surprise and a big shot in the arm. I think the other surprises were these very clear financial sector commitments about insurance companies ready to shift their investments. That's big. And I think the other thing that came out was the need and the desire for a long-term goal to go to zero-carbon by mid-century. That was stated by a number of companies and by countries, and it just really shows there's a collective vision that's building.

CURWOOD: How did you feel about the demonstration, Jennifer, on the 21st [of September], people marching in New York? I imagine you were marching with them as well.

MORGAN: I was there, and I have to say I think it was one of the most exciting, dynamic things I've ever been part of. I think it was an outpouring from just so many different people: young, old, business, government, city, labor. Everyone was there, and I think it really gave a boost to the Summit because it showed that the people do want climate action and now the politicians have to respond.

CURWOOD: Jennifer Morgan is Director of the Climate and Energy Program for the World Resources Institute. Thanks so much for taking the time today.

MORGAN: Thank you.

Related links:

- Jennifer Morgan’s analyzes outcomes from the U.N. Climate Summit on WRI’s blog

- Read Ban Ki-Moon’s Opening Speech at the U.N. Climate Summit

- WRI’s Live Blog of the Climate Summit

- Pictures, videos and tweets from The People’s Climate March—the largest climate march to date. The energy carried over from the March into the Summit.

Beyond the Headlines

Lyme disease is spread by tick bites and, thanks to climate change, the disease’s geographic range is projected to increase over the coming decades. (Photo: John Tann; Flickr CC-BY-2.0)

CURWOOD: We turn now from climate week events to stories beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. He’s the publisher of Environmental Health News, that’s ehn dot org as well as Daily Climate dot org. He’s on the line now from Conyers, Georgia. So Peter, what did you find for us today?

DYKSTRA: Well, hi Steve. I’ve come armed with a story from the Western U.S. and another one from the Eastern U.S., but I can’t promise you that either story is terribly cheerful.

CURWOOD: Uh, Oh. Well, give me the bad news first, and then give me the other bad news.

DYKSTRA: Well if it’s any consolation, the bad news comes in the form of really good journalism. The first, National Geographic Magazine this month has a stunning portrayal of how much worse the western drought could get, and it all boils down to snowpack. In a series of images and graphics, writer Michelle Nijhuis and photographer Peter Essick look at the key to western drought, and that, of course, is the snowpack.

CURWOOD: And I take it the trend for snowpack isn’t good, huh?

The California Aqueduct shuttles water from the north, where snowmelt is abundant, to the farms and metropolitan areas of the south. But climate change and the shrinking Sierra snowpack leaves the southern region in a condition of severe drought. (Photo: John Loo; Flickr CC-BY-2.0)

DYKSTRA: Well, the only question left is whether western snowfall is in a major slump, or if it’s declining for good. We’ve turned dry, even desert land into farms and cities like Phoenix, L.A., San Diego, and Las Vegas. We’ve literally built the Western U.S. and much of our food supply on the assumption that melting snow would forever give water to the region, but now, all bets may be off.

CURWOOD: Well, that’s depressing. And you said you had some gloom from the Eastern U.S., as well.

DYKSTRA: I do: Lyme disease, that source of discomfort and fatigue for millions of Americans, appears to be spreading, and climate change is a likely suspect.This week as part of our new “Climate At Your Doorstep” project, reporter Marianne Lavelle looked at the projections for how Lyme disease may spread over the next several decades to cover much of North America.

CURWOOD: And we’re talking about an illness spread by ticks that, in our lifetimes, Peter, was once confined to parts of Connecticut and Long Island.

DYKSTRA: Right, but by the year 2080, researchers project that Lyme disease hotspots might range in warming winters from Omaha to Ontario to Orlando.

CURWOOD: Boy, Peter, you’re just full of great cheer this week.

DYKSTRA: Well, I guess there are worse things to be full of.

CURWOOD: Okay, well, bring us something now from the environmental history vault, please.

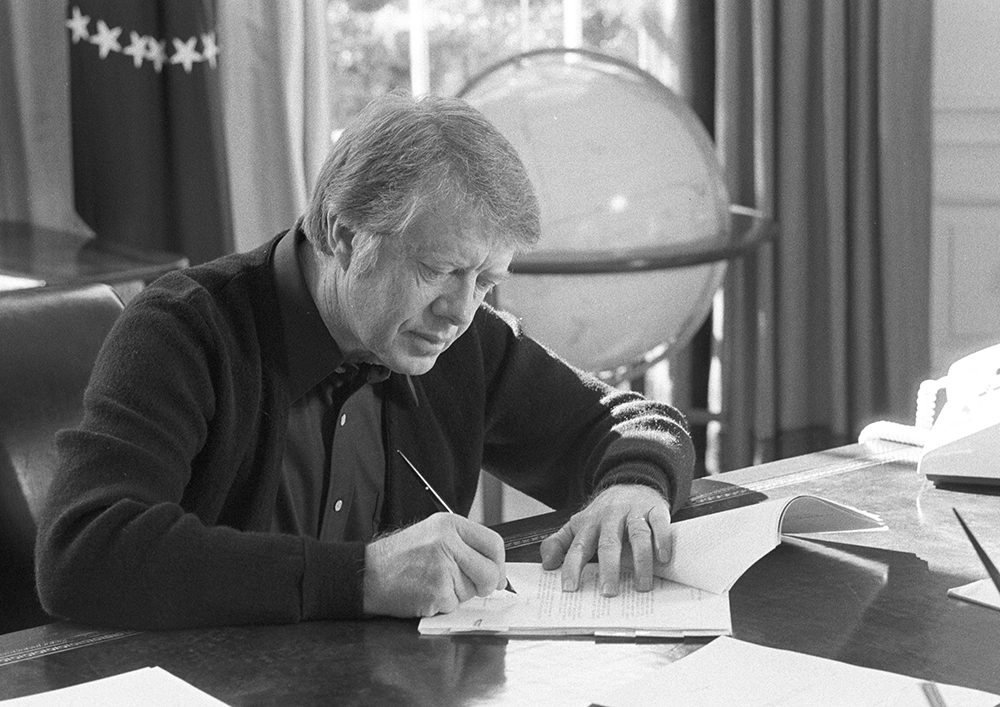

DYKSTRA: Well, it’s a little bit of a departure from the climate theme we’ve had for this show, but thirty-five years ago this week, President Jimmy Carter dealt one of the first assaults on the U.S. Endangered Species Act by giving in a little. There’s a tiny fish called the snail darter, known to exist only in one stretch of the Little Tennessee River, and it was blocking the completion of a massive dam. This little fish became a poster child, or maybe a poster fish, for both supporters and opponents of the Endangered Species Act.

CURWOOD: And President Carter felt he was stuck between a fish and a hard place.

Thirty-five years ago, then-President Jimmy Carter signed a bill exempting the Tellico Dam project from the Endangered Species Act, which protects endangered species like the snail darter—a small fish. This angered environmentalists. (Photo: Children’s Bureau Centennial; Flickr CC-BY-2.0)

DYKSTRA: Right, so he signed a bill exempting the Tellico Dam project from the Endangered Species Act, which upset environmentalists who saw it as a hole being poked in their legal dam to protect species.

CURWOOD: But as I recall, the dam got built, and the snail darter is still with us, right?

DYKSTRA: Correct on both counts. The Tellico Dam was almost complete when Jimmy Carter ended the controversy back in 1979. What happened was some snail darters were relocated from the Little Tennessee River to another river, and then they found other snail darter populations elsewhere. But there have been countless endangered species poster animals since then, from the Spotted Owl to the Desert Tortoise.

CURWOOD: So, is that good news that the snail darter still exists, or is it bad news, that even President Carter didn’t protect the fish or defend the law?

DYKSTRA: Well, it’s probably a little of both. We still have the Endangered Species Act, and it’s being both assaulted and protected today.

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra is the publisher of Environmental Health News – that’s EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. Thanks so much for taking the time today, Peter.

DYKSTRA: All right, Steve, thanks a lot. We’ll talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there’s more on these stories at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Writer Michelle Nijhuis and photographer Peter Essick collaborate to depict a snowpack dwindling in the West.

- Read the “Climate At Your Doorstep”, projecting the spread of Lyme disease

- Erection of the Tellico Dam threatens the snail darter, a small endangered fish.

BirdNote® A River of Raptors Over Veracruz

In Living on the Wind: Across the Hemisphere with Migratory Birds, author Scott Weidensaul describes watching hundreds of thousands of raptors circling on columns of rising warm air. (Photo: BGV23; CC)

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

CURWOOD: Well, the changing weather is already affecting the natural world and that includes birds and their migrations, with some species starting earlier or staying later. But in the right place at the right time, you can see the most spectacular sights – as Michael Stein tells us in today’s BirdNote®

http://birdnote.org/show/counting-million-raptors-over-veracruz

BirdNote®

Counting a Million Raptors Over Veracruz

Featuring Scott Weidensaul

[Musical selection from “Tree of Life” by Nancy Rumbel]

STEIN: In September, a river of raptors flows through Veracruz State in eastern Mexico.

In his book, Living on the Wind, Scott Weidensaul [WHY-den-saul] describes counting the birds there as they circle in “kettles” on columns of rising warm air and then drift steadily south.

[narrator reads from Living on the Wind]

“Nothing in a lifetime of birdwatching had prepared me for this spectacle. The kettles grew to almost frightening proportions, twenty or thirty thousand hawks in each one.”

Wiedensaul and his companions counted nearly 46,000 broad-winged hawks in one ten-minute period. (Photo: Putneypics; CC)

STEIN: “From two to three o’clock we counted 126,516 broad-winged hawks, nearly 46,000 of them in one ten-minute period. The next hour there were even more, along with nearly 11,000 turkey vultures. A steady stream of kestrels was moving low along the horizon, passing at a rate of five per minute, their wings flashing in the sun like a thin reflection off the distant Gulf."

“And so it went for hours. From our hot, dusty rooftop in Cardel, we had counted more than 435,000 raptors. As our sense of numbed disbelief gave way to comprehension, we realized we had witnessed – by far – the heaviest hawk migration ever recorded, anywhere in the world.”

Since that day in 1992 the record has been far eclipsed. Some days more than a million birds have been counted passing through the narrow, vulnerable corridor of Veracruz.

I’m Michael Stein.

In September, a “river of raptors” flows through Veracruz State in eastern Mexico. (Photo: Courtesy of Tom Grey)

Today’s show brought to you by the Bobolink Foundation. Find a link to Weidensaul’s book at birdnote.org.

Written by Todd Peterson

“Tree of Life” composed and played by Nancy Rumbel; album Notes from the Tree of Life, Narada, 1995.

BirdNote’s theme music was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Chris Peterson

© 2014 Tune In to Nature.org September 2014 Narrator: Michael Stein

http://birdnote.org/show/counting-million-raptors-over-veracruz

CURWOOD: And to find some picture of the raptors that gather over Veracruz – soar on over to our website LOE dot ORG. Coming up: Writer Naomi Klein on why climate change changes everything—including economic growth and capitalism. That's just ahead on Living on Earth – stay tuned.

Related links:

- Discover the BirdNote® website

- Living on the Wind: Across the Hemisphere with Migratory Birds by Scott Weidensaul

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems provides building technologies and supplies container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food, and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

Capitalism vs. The Climate

Klein spoke at the Flood Wall Street event on September 22nd, highlighting how a broken capitalist economy contributes to the climate crisis. (Photo: The All-Nite Images; Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Among the climate marchers in New York City was Naomi Klein, the activist and best selling author known for incisive critiques of U.S. foreign policy and corporate power. In recent years she has turned much of her attention towards the climate crisis, joining the divestment movement and the fight against the Keystone XL pipeline. Her newest book is called This Changes Everything, Capitalism Versus the Climate and it argues that solving climate change will require that we challenge the entire logic and structure of the deregulated capitalist economy. We caught up with her in New York shortly after the massive climate demonstrations.

Welcome to Living on Earth!

KLEIN: Thank you. So good to be with you.

Anti-capitalist sentiments ran high at the People’s Climate March in New York City on September 21st, 2014, a day before the Flood Wall Street protest. (Photo: The City Project; Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: One of the things that's really fascinating with this book this is you present climate change in its historical context. It doesn't exist in a vacuum, it's part of this history of globalization and trade and development. So what is the connection between free-trade and global warming in your view?

KLEIN: Well, we know that the global economy has been expanding very, very rapidly, and it's been expanding on a very particular model, which is all about removing the barriers to investment and manufacturing. This is what allows corporations to set up shop in free-trade zones in China and move their goods around the world and so on, and it's a very, very profitable model. It's also very high carbon model, not just because of the transport, but also because - and I argue in the book - that that there is a connection between cheap labor and cheap energy, and cheap energy tends to be coal. Right? So if you are multinational and your only goal is to lower your production costs, and that's really been the story of our era, then it isn't just that you're to find the cheapest, most exploited labor force in the world. But in that relentless drive to push down costs, you are also going to see a race towards ever dirtier energy. So at the same time as industrialized countries in Europe and United States and Canada and elsewhere are actually lowering their emissions and cleaning up their industrial production, and wages were going up when production moved to countries like China, not only did wages go down, but emissions went up.

In her new book, This Changes Everything, Klein argues that globalization and free trade drove climate change. (Photo: naomiklein.org)

CURWOOD: So that means that if I buy an air conditioner that was made in China with cheap energy, that my emissions in the U.S. are low, but I just raised China's?

KLEIN: Yes, sometimes we pat ourselves on the back in countries like the U.S. and Europe that our emissions are not going up as quickly or even going down a little bit in certain years. The problem is our goods are overwhelmingly produced in other parts of the world now, and the emissions associated with those goods are accounted for entirely on the ledgers of the countries that do the production, so your air conditioner, your television, if it was made in China—then China is the one who's responsible for all those emissions. And then the weird thing is that the emissions for transporting that air conditioner and TV are not counted towards any country's emission. They're just not accounted for.

And so, I talk about how you had these two parallel processes of international negotiations that were going on at the same time - the climate negotiations and then on the other hand the trade negotiations. And the weird thing is one pretended the other wasn't happening. It's like these two conversations were just entirely parallel and not intersecting, so the rules that were locked in when trade agreements like NAFTA were signed put up barriers for governments that wanted to enact good green energy programs. So for instance I live in Toronto, which is in Ontario—my government actually passed a really ambitious green energy plan, and there's a requirement that if you want to benefit from the subsidies, you have to produce a certain amount of your solar panels and wind turbines in Ontario. It was successful: 31,000 manufacturing jobs were created, closed down auto plants opened up and were turned into solar production plants; in the green economy that everybody talks about. And then Japan and the European Union took Canada to the WTO and said that this violated our obligations because you're not allowed to favor local industry, and in fact, there have been several trade challenges like this: the U.S. has challenged China, has challenged India, for its subsidies it supports for renewable energy.

In the midst of Climate Week in New York City, Steve Curwood sat down with Naomi Klein to discuss her new book, This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. The Climate. (Photo: Emmett Fitzgerald)

KLEIN: And to me it's just extraordinary because here we are in this moment where we want every government in the world to be doing everything possible as fast as they can to roll out renewable energy, and you go to a Climate Summit and all these governments are pointing the finger at each other. "No, you're not doing enough. No, you’re not doing enough." And then another wing, a more powerful wing of these governments, are running to the World Trade Organization and trying to knock down each other's windmills.

CURWOOD: I take it the bottom line of your book here is, if we want to solve the climate crisis, we have to change economic system, huh?

KLEIN: We do, and I think it's deeper than that. I think we need to have a debate about what kind of values we want to govern our society and the issue of bad timing that I lay out in the book, is that this crisis hit us with a certain set of values, sort of hyper-individualism—Margaret Thatcher's theory is there is no such thing as society, this idea that all we are is consumers—these were the values that came to govern. They're not the values that have always governed. This was a shift and it was a political project by a relatively small group of people that really set out to change the hearts and minds and change the culture. And it works to a great extent, but not completely because we know we're more than that. You know, especially when crises hit we see other sides of ourselves, that we can and want to act collectively. And so I think there's been this way in which we've been trying to respond to the climate crisis without rocking the boat, rocking the economic boat. So we'll appeal to people as consumers: It's all about changing light bulbs, buy a hybrid, buy some carbon offsets. This is the model that has dominated for 20 years.

The Revolutionary Communist Party was just one of several anti-capitalist groups at the People’s Climate March. (Photo: Jean Gazis; Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So let me ask you this: so the environmental movement, which has been sounding the alarm about climate has been trying to work within this economic model. How's that been going?

KLEIN: Well it hasn't been going very well. In the 1960s and ’70s and really up until 1980 when the Superfund Act was passed in the states, it was about polluter pays, right? You've got a pollution problem; the polluter's responsible. We're not just going to pass a new law, we're going to try to get the polluters to pay for the cleanup. Then comes the ’90s and climate change and it's, well, "No, no, no, it's polluter plays. We'll sit down with the polluters and we'll convince them that this is in their best interest. And we'll form a partnership, and we'll show Walmart that they'll save money if they introduce energy efficiency”. And you know what, it does. It saves money for Walmart to become more energy-efficient.

The problem is, Walmart is a company that, as we all know, is driven by an ethos of relentless growth just as our economy is, and though they are more energy-efficient, their carbon emissions continue to rise because they expand so rapidly. So this model of just trying to cajole corporations to introducing voluntary measures plus some consumer responses, it doesn't add up, and the carbon record doesn't lie. And if we mean what we say, when we call this "the greatest crisis facing humanity" to quote the Secretary-General of the U.N. or a "weapon of mass destruction" to quote John Kerry, if we believe this and we should, then why would we leave this to the boom and bust cycles of the market? Wouldn't we try to take the wheel and respond as we do in the face of grave threats?

A crowd of approximately 3,000 people carried signs and banners at the Flood Wall Street event on Monday September 22nd, 2014. (Photo: Stephen Melkisethian; Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: What's wrong with market-based mechanisms to deal with the carbon crisis, say something like cap-and-trade?

KLEIN: Well, we've been trying to deal with it this way, and I think, you know, that some of these mechanisms can work for smaller problems. The problem is that carbon is at the center of our economy. It's what our economies are built on. They're built on fossil fuels. So the changes required are just simply too great, and the market can get us partway there, but it can't get us all the way there. So it also requires some serious regulation. Europe has the largest carbon market in the world, and what we've seen is it's subject to all these problems: the housing market, they created a bubble, the price of carbon collapsed. It was also a magnet for fraud.

CURWOOD: So you say America lucked out not having Congress pass a cap-and-trade program.

KLEIN: Well, the cap-and-trade law was very much a product of this “polluter plays” model of environmental regulation. It was based on the logic that we aren't going to get anything done unless we can get the polluters on side. So, the model, and it was pioneered by the Environmental Defense Fund, was to bring some of the biggest carbon polluters in the country: big oil companies like BP and Chevron, Duke Energy, to sit around the table with a few environmental groups—there were many more corporations than there were environmental groups—and to hammer out an agreement. Well, imagine if we tried to do the same thing with the banks. What kind of agreement do you think you'd come up with? I think we kind of know. That's exactly what we've had. And so they came up with an agreement that really gave them a free pass that passed the cost to consumers. It also was a system that would allow coal companies to keep emitting so long as they offset those emissions by protecting a forest somewhere else or funding solar energy in another country, and that also takes away from the real energy towards climate action.

Protestors who ‘flooded’ Wall Street drew a direct connection between capitalism and “climate chaos.” (Photo: Susan Melkisethian; Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Like if you look at who came out to that climate march in New York—it was communities where kids have asthma, and they are already dealing with the real impacts of this toxic economic model. And so once you set up this carbon market offset system, it's called win-win but it's actually lose-lose because the people whose kids have asthma are still dealing with that. They don't get the refineries shut down and replaced with clean energy, and then often people on the other side of the world whose land is deemed a carbon an offset also lose because they often lose access to their land and their forest becomes a kind of tree museum that is all just about capturing carbon. And they're not able to engage in subsistence logging, in subsistence agriculture.

CURWOOD: So is your book criticizing capitalism or is it more simply about big oil, whether it's capitalist or not? I mean, Russia has gas, China has a huge petrol company, Statoil in Norway. There are other big private companies, but there are big public ones.

KLEIN: Well the book is about a clash between a logic: this logic of short-term growth, short-term profits above all else, and what we need to do to solve this climate crisis which is, I think, respond strategically, and that means that we need to contract certain parts of our economy and expand other parts of our economy. And whether it's a state-owned company at this point or a privately held company—they're all traded on stock exchanges, and they're all in the grips of the same logic. So, yeah, Statoil, is a publicly traded company even though it is still state-owned, and despite the fact that Norwegians are very concerned about climate change and have tried to pressure Statoil to pull out of the Alberta tar sands and to back away from Arctic drilling, they found that it's very difficult to get the company to be responsive. But still, I do think that having some of these energy companies in public hands, there's more of a chance of changing them. I think the Norweigans have more of a chance ultimately of changing a company like Statoil and capturing the enormous profits from fossil feels and using those profits to get us off this path. I mean, this is the issue: We need to return to a “polluter pays” model because we're told all the time that our government's are broke. We can't accept that as a response to climate change, and that means we need to go to where the money is, and luckily, fossil fuel companies are the wealthiest industries in the world. No company has ever made more than Exxon Mobil. And we need to find ways to capture more of those profits to pay for this transition.

Naomi Klein (Photo: Nicolas Haeringer; Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: You write at one point in your book, and I'm quoting you here, "The resources for this just transition must ultimately come from the state, collected from the profits of the fossil fuel companies in the brief window left while they're still profitable".

KLEIN: I mean, that seems logical enough to me. It's a principle that was applied to the tobacco companies, once tobacco profits were deemed to be illegitimate, in the sense that the science was in and documents were revealed that showed that the tobacco companies understood the link between smoking and cancer and were denying it. The same sort of dynamic is emerging with the fossil fuel companies and that's why you have this very fast-growing fossil fuel divestment movement, very much driven by young people and faith communities who are saying, “these are immoral profits. It's immoral to profit from a business model that knowingly is destabilizing our home, our life-support systems”.

So I think once we recognize that, then we need to capture more of them, and we need to use them to get off those sources of energy because it's an expensive process, and nobody else is offering the money. It's not just the fossil fuel companies that need to finance this, but it's impossible to imagine us responding to this crisis in the way that we must without having that, what I call in the book "the battle of world views", right? Because so many of the certain, reasonable, rational things that we need to do in the face of this crisis have become taboo. "You don't plan an economy, what you talking about?" Increasing taxes, you're not allowed to talk about that, taxation and regulation, all of these. This is the legacy of the ideological project that was launched in the 1980s and this is why climate change had the worst possible timing, it landed on our laps when all of the tools that we needed to respond to this crisis were being taken out of our hands. We need to take them back.

Hundreds of people helped carry a three-hundred-foot-long banner that read, “Capitalism = Climate Chaos – Flood Wall Street” at the Flood Wall Street event Monday. The banner had also made an appearance a day earlier, at the People’s Climate March. (Photo: A Jones; Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So how do we do this? And how long do we have to do this, I mean, both from a climate perspective and an economic one?

KLEIN: Well, look, I think the good news is that more and more people realize that we need a different kind of economic system, whether or not there is a climate crisis. There is an inequality crisis; it's extremely deep in the United States. And the level of dissatisfaction with deregulated capitalism is higher than it's been since the 1930s. People want a better system, and in fact they know that if we were to respond decisively to this challenge, the investments in the public sphere, the investments in renewable energy, would create many, many more jobs than the fossil fuel economy is offering now. And so we don't have a lot of time; I mean, we're on a deadline. I happen to think that deadlines can be helpful, but I think we're on a deadline for a lot of reasons. I think the inequality crisis is just as pressing as the climate crisis, and if we can bring these two discussions together, then I think we can start moving very quickly.

CURWOOD: In your book you say activism is rising because what you call "extractivism" has wound up here in America. It's not just overseas, in colonies, but it's happening in communities that are facing fracking and that sort of thing. How do you think that's changing the political discussion?

KLEIN: Well, the truth is our economy has always required sacrifice zones, sacrificial people and sacrificial places. This is the story of the founding of this country, whether the sacrificed people were slaves or whether the sacrificed places were the coal mining communities and the coal miners. So it's not that extractivism and the impacts of extractivism are new, it's that everybody is in the sacrifice zone now, and it's building alliances between different constituencies that had previously been separated.

CURWOOD: So in your book, you hold up grassroots political protest as really just about the only thing that's going to get us from where we are now to a climate-friendly future. What did if feel like to march here in New York?

KLEIN: Well, it felt great. I mean, the People's Climate March was an extraordinary experience. It wasn't just that it was huge, and it was - I've never participated in a larger demonstration - it was that it was completely unlike any climate event that I have been a part of. I was in Copenhagen in 2009, and I was at the Forward on Climate March in front of the White House protesting the Keystone XL pipeline. This felt different because it looked and felt like New York City. It was not an NGO organized event, although NGOs were involved. It really was a people's climate march, so the indigenous people who were at the front of the march, a lot of them came from Alberta, Canada, who are living downstream from the tar sands are dealing with very high cancer rates, are dealing with the fact that the animals that they've always depended on are getting sick.

Author Naomi Klein with our host Steve Curwood and producer Emmett FitzGerald in New York for the climate rallies. (Photo: Julia Prosser)

And then you have people from New York State who are trying to protect a moratorium on fracking and are worried about their water supplies. So I think that what's so significant about this wave of organizing, is that it has such a powerful sense of urgency, that it is about children's health. It is about people losing their homes to Superstorm Sandy. It's about the connection between this global crisis and how it's playing out locally, whether with the effects of climate change or the direct impacts of fossil feel extraction or combustion or transportation. I personally don't believe that grassroots resistance is going to get us to where we need to go, in that we need national bold policies; we need international treaties. You know, it's not just going to be the resistance at the community level that will get us there, but right now these are the signs of hope. It's the people who are doing what the politicians won't do, which is say to the fossil fuel companies, "You have to keep this carbon in the ground".

CURWOOD: Naomi Klein's new book is called "This Changes Everything: Capitalism Versus the Climate". Thanks for taking the time today.

KLEIN: Thank you. It was a great conversation.

[MUSIC FROM THE PEOPLE’S CLIMATE MARCH]

Related links:

- This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. The Climate by Naomi Klein

- Naomi Klein’s website

- Watch Naomi Klein on The Colbert Report

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jenni Doering, Lauren Hinkel, Jake Lucas, and Jennifer Marquis all help to make our show. James Curwood engineered the show, with help from Karlyn Daigle and special thanks to Nole Flatt. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us on our Facebook page - It’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more. www.stonyfield.com.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth