Beyond the Headlines

Air Date: Week of December 5, 2014

In the 1980s, a flurry of reporting on the potential link between high-voltage power lines and cancer created an atmosphere of fear that persists today, despite the lack of evidence linking the two. (Photo: Hope Abrams, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

In this week’s trip beyond the headlines, host Steve Curwood and Peter Dykstra discuss the largely unproven connection between powerlines and cancer, why thalidomide wasn’t used in the U.S., and Prohibition’s long-term effect on ethanol as a fuel.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Time to take a trip to Conyers, Georgia, for a look beyond the headlines. Our guide as usual is Peter Dykstra. He publishes Environmental Health News, EHN.org and the DailyClimate.org, and he's on the line now. What’s on tap today, Peter?

DYKSTRA: Well, I'm all about history this week Steve, but let's start with a story that a lot of folks may have gotten wrong. A New York Times feature called the Retro Report tracked this one down. Back in the 1980s there was a flurry of reporting, and a frenzy of activism, over the potential cancer risk from radiation coming from high-voltage power lines.

CURWOOD: Now, there actually were studies that said there's a possible link between electromagnetic radiation from powerlines and leukemia, right?

DYKSTRA: Right, back in 1979, there was indeed such a study suggesting a link as well as another big study in 1987, but in the years since, many subsequent papers haven't really built on those findings, and speaking in epidemiological terms, 35 years is plenty of time to establish health patterns. A few scientists still continue to research the link, while some others say there's little chance at this point that radiation from powerlines is a human health threat.

CURWOOD: So if the research hasn't come in to back up the original concerns, are we mostly dealing with a fear factor here?

Frances Oldham Kelsey, who recently celebrated her 100th birthday, withheld approval of thalidomide for use in the U.S. In 1962, President Kennedy awarded Kelsey the President's Award for Distinguished Federal Civilian Service for her refusal to cave to the pharmacological industry’s pressure. (Photo: Luciana Christante, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Possibly. Some folks in the media have been known to play up scary things, and this one has all the ingredients: fear of cancer, particularly in kids, a risk we can’t control. There might be other reasons to be concerned about powerlines: in many parts of the country, rights-of-way for powerlines are still maintained by applying a healthy dose of pesticides, and also, huge steel towers and cables galloping through the countryside are just plain butt-ugly. That last one isn't peer-reviewed, but it seems to be a universal feeling. Bottom line: after 35 years of scrutiny and study, there's still no smoking gun to show a significant health threat exists from powerlines.

CURWOOD: And the other bottom line is that most environmental science gets validated over time, but not all, or at least so far. What's next?

DYKSTRA: A story from the Globe and Mail in Canada about a true science hero. Frances Oldham Kelsey is a hundred years old now but in 1960, she was a mid-level bureaucrat at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. If you were born in the US in the early '60s, Frances Kelsey may very well have saved your life.

CURWOOD: I think you may have just gotten some people's attention.

DYKSTRA: Yeah. Thalidomide was a wonder drug widely used in Europe and Canada in the late 1950s. It was prescribed as a sedative, and for pregnant women, it made morning sickness go away. There was a clamor to approve thalidomide for use in the U.S. and all that stood in the way of FDA approval was the sign off from medical officer Frances Kelsey. She had some serious questions about side effects from the drug, and despite relentless pressure from the manufacturer, she stood her ground until those questions were answered.

CURWOOD: And anyone who knows the history of thalidomide knows that those answers came in the form of a health disaster.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, in the countries where thalidomide was rushed to the market, it's blamed for thousands of deaths or serious deformities in the children of the pregnant women who took it. The US escaped the disaster, all because one government worker stood up to pressure and put health and safety first.

CURWOOD: Ah, so it's possible to be a government bureaucrat and a hero at the same time, huh? Now, what do you have on the history calendar this week?

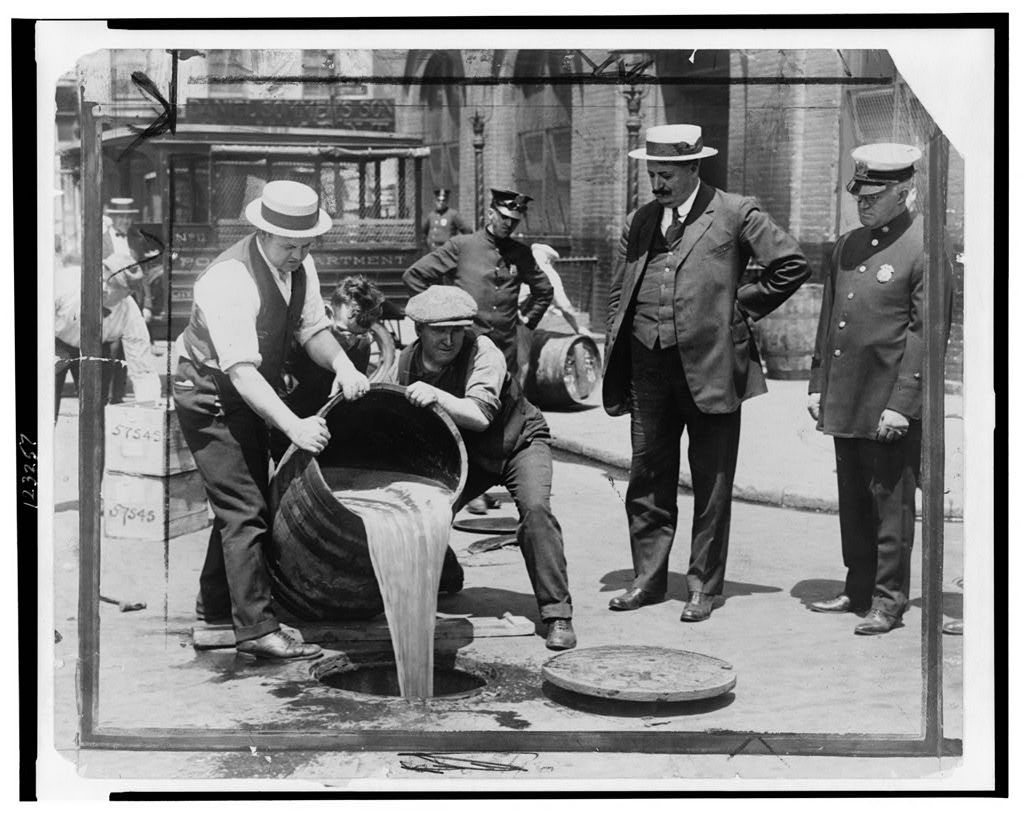

Since ethanol was banned during the Prohibition era, engineers designed motors to be gasoline powered. Subsequent models built upon these, causing lasting consequences for the U.S. energy infrastructure. (Photo: Dewar’s Repeal, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Eighty-one years ago this week, Prohibition was repealed, and America could legally drink once again, not that that many people had been deterred by the law in the first place. But Steve, the end of Prohibition had a huge environment and energy angle as well. Alcohol for drinking was still made, and sold, and smuggled throughout the Prohibition era and it helped build the Mafia and gangsters and all sorts of TV shows and movies, but when the making of alcohol was banned, ethanol for fuel was effectively outlawed as well because ethanol, most commonly made from corn these days, is essentially alcohol.

CURWOOD: Which in turn, put gasoline in the driver’s seat as the fuel of choice for cars.

DYKSTRA: Well, it didn't literally put gasoline in the driver’s seat, I believe that's still illegal, but yeah. Two titans of the early 20th century took opposite sides on Prohibition. Henry Ford was opposed because his iconic Model T cars were designed to run on ethanol. John D. Rockefeller and his oil business viewed ethanol as his main competition, so he was very pleased to see it outlawed.

CURWOOD: And only in recent years has ethanol recovered, but then again, corn-based ethanol has more than its share of critics today, right?

DYKSTRA: Pretty much. It made something of a comeback on both sides in World War II, when oil and gasoline were in short supply. The Germans actually fueled their V-2 rockets with ethanol. Renewable energy standards today give us a blend of ethanol and gasoline. The corn belt loves ethanol, Presidential candidates praise it while passing through Iowa, but its pollution burden and its real value are subjects of debate. But Prohibition and its ban of ethanol from 1919 to 1933 tipped the scales in favor of gasoline, and it changed the course of history.

CURWOOD: Well, thank you, Peter. Peter Dykstra is the publisher of Enviromental Health News – that's EHN.org and the DailyClimate.org. Talk to you soon!

DYKSTRA: Alright, Steve, talk to you soon!

CURWOOD: And there's more at our website, LOE.org.

Links

The fear of power lines’ link to cancer, as report by the New York Times

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth