December 5, 2014

Air Date: December 5, 2014

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Supreme Court To Hear Challenge to Power Plant Mercury Rule

View the page for this story

President Obama is using EPA authority under the Clean Air Act to try to curb dirty power plant missions including CO2 and mercury, but coal interests are fighting back in the courts. Vermont Law Professor Pat Parenteau tells host Steve Curwood that the latest of Obama’s regulations to wind up before the Supreme Court is the Mercury Rule. (08:00)

Coal Baron Indicted in Mine Disaster

View the page for this story

In 2010, in one of the deadliest mine accidents in US history, an explosion at the Upper Big Branch Coal mine in West Virginia killed 29 miners. Now Don Blankenship, the CEO of mining company Massey Energy, is facing federal criminal charges related to the disaster. Law professor Patrick McGinley talks to host Steve Curwood about the case. (07:10)

Human Rights On the UN Climate Change Agenda

View the page for this story

For years, national leaders have failed to create sustainable climate change solutions, and poorer nations and communities have borne the brunt of inaction. In conversation with host Steve Curwood, the Daily Climate’s Science Writer Marianne Lavelle discusses how human rights issues are now getting interwoven with climate change solutions and that future agreements must account for this. (06:10)

Rhinos For Sale

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

Poaching African rhinoceros for their horns has pushed to them to brink of extinction. Today, there are only 25,000 rhinos left in the world, 85-percent of them in South Africa. Now a national park there is selling off some of its rhinos to relocate and protect them. Bobby Bascomb reports from Pilanesberg National Park. (06:55)

Place Where You Live: Gaborone, Botswana

/ Karin VermilyeView the page for this story

Living on Earth is giving a voice to Orion Magazine’s long-time feature, The Place Where You Live, where people write essays about their favorite places. This week, we hear from Karin Vermilye in Gaborone, Botswana, a city where water scarcity is an ever present concern. (04:05)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s trip beyond the headlines, host Steve Curwood and Peter Dykstra discuss the largely unproven connection between powerlines and cancer, why thalidomide wasn’t used in the U.S., and Prohibition’s long-term effect on ethanol as a fuel. (05:05)

Beinecke's Message of Hope for a Planet In Peril

View the page for this story

After four decades of working for the Natural Resources Defense Council, its president Frances Beinecke is stepping down. Host Steve Curwood discusses her life, and her new book, The World We Create, with its message of hope for the future of the environmental movement and the Earth. (09:50)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Pat Parenteau, Patrick McGinley, Marianne Lavelle, Karin Vermilye, Frances Beineke

REPORTER: Bobby Bascomb, Peter Dykstra,

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. Coal-fired power plant owners appeal yet another clean air rule to the US Supreme Court.

PARENTEAU: The law is finally catching up with the health effects and the environmental effects of coal-fired electricity. The coal industry has enjoyed a lot of benefits and a lot of exemptions from strict environmental regulation and those days are over, and I think its fair to say that coal's days are numbered.

CURWOOD: Also, rhinos in Kruger Park in South Africa are being killed because their horns are so valuable on the black market.

HENDRICKS: Poaching takes advantage of the high level of poverty around Kruger. Poaching is a problem simply because there’s high monetary values involved. If someone is poor then obviously it’s an easy access to money.

CURWOOD: Plans to move the rhinos may help. That and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies – innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable, place to live.

[THEME RETURN]

Supreme Court To Hear Challenge to Power Plant Mercury Rule

The Clean Air Act regulates pollution coming from power plants. (Photo: bigstockphoto)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. The Clean Air Act is one of America’s most important environmental laws, and using its authority, President Obama’s EPA has imposed stricter mileage requirements for vehicles and restricted smog crossing state lines. But industry strongly resists the use of this act to clean up power plants, especially to curb carbon dioxide, and mercury and other toxins from coal. The EPA says its latest rule to cut toxic power plant pollution would prevent up to 11,000 premature deaths from cancer and respiratory illnesses. But coal power plant operators say the rule would cost too much money and the US Supreme Court has agreed to hear their appeal. Pat Parenteau is a Professor of Environmental Law at Vermont Law School and he joins us to talk about the case. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Pat.

PARENTEAU: Thank you, Steve.

CURWOOD: So, what exactly is the mercury rule anyway?

PARENTEAU: The mercury rule is under section 112 of the Clean Air Act that regulates hazardous air pollutants from among other things, coal-fired power plants. Mercury and arsenic are two of the primary pollutants and coal-fired power plants emit about 99 percent of mercury and arsenic in the country.

CURWOOD: And why is the coal industry challenging this rule?

PARENTEAU: Very expensive rule, almost $10 billion by EPA's estimates to comply, but also EPA asserts that the rule will create about $90 billion in health benefits from cleaning up mercury pollution through scrubbers.

CURWOOD: Now what did the Court of Appeals in DC say about the industry's complaints?

PARENTEAU: The Court of Appeals upheld EPA's rule by a 2-to-1 vote, and there was a dissenting vote by Judge Cavanaugh, claiming that EPA should have considered the costs of the rule when it decided it was appropriate - that's the word of the statute - to regulate hazardous air pollutants from coal-fired power plants. So the DC circuit said EPA had discretion to regulate these emissions based on health effects and did not have to consider their costs.

If upheld, the Mercury Rule would require coal-fired power plant operators to take extensive and expensive actions to clean the emissions coming from their plants. (Photo: bigstockphoto)

CURWOOD: So the dissenting judge’s view that cost should be considered is that what got the industry a ticket to the Supreme Court?

PARENTEAU: Yes, the statute is vague; it says that EPA may regulate where “appropriate and necessary” after studying the issue, and EPA's been studying hazardous air pollutants like mercury for over 10 years until it finally decided to take very decisive action and require that all these new and existing coal-fired power plants install scrubbers to take the mercury out.

CURWOOD: What you think of the chances that industry gets its way and the Supreme Court reverses the Appeals court and the EPA and the rule gets thrown out?

PARENTEAU: Well, anytime the Supreme Court takes a case it's usually not to simply affirm the lower court, so at least four justices out of the nine justices have some questions about why EPA didn't consider costs. It's interesting that the court reframed the question presented differently than the way the industry had framed it, and basically the court has said was it reasonable for EPA to decide that costs were not relevant to the consideration of regulation on the basis of health benefits. So the question, as the court has framed, is narrower than what the industry was looking for. That might mean that the ultimate decision could be a close decision, 5 to 4, for example, but it might well uphold EPA's discretion since the statute doesn't mandate that EPA must consider cost. So the court may say it's reasonable for EPA to say it doesn't have to consider the costs.

CURWOOD: Now, when in the past has the High Court looked at the costs of implementing pollution protections?

PARENTEAU: The main case is called the American Trucking Association case. This was a unanimous decision of the Supreme Court several years ago, and the question there dealt with what are called National Ambient Air Quality Standards. These are things like smog and soot and lead, and in that case the court said not only was EPA not required to consider costs, it wasn't allowed to consider costs. Now the language of the provision at issue in the American Trucking case is different than the section 112 provision that's at issue in the mercury case, so there's different language to be interpreted and that's why perhaps the earlier case isn't necessarily binding precedent. But it does show that the Supreme Court has in the past said that costs really aren't a relevant consideration when you're talking about human health.

Pollution from coal-fired power plants can be dangerous, and the EPA claims that, by limiting harmful emissions, the Mercury Rule could prevent human exposures and as many as 11,000 premature deaths every year. (Photo: bigstockphoto)

CURWOOD: How important is this case, and in particular, how is the challenge to the mercury rule related to the efforts by the administration to put in rules to regulate power plants for CO2?

PARENTEAU: Yeah, that is a very interesting question because the power plants are now subject to regulation under two different provisions: section 112 which regulates the hazardous pollutants and section 111(d) which regulates carbon, and interestingly enough the industry groups that are now claiming that EPA's mercury rule is invalid, are the same groups that are claiming in the rule challenge to the carbon rules, that EPA doesn't have authority to regulate coal-fired power plants because they are already regulated under section 112. So if the court overturns the mercury rule on the grounds that it was improperly adopted under section 112, that will undercut the industry’s arguments that EPA can't regulate carbon emissions from coal-fired power plants under this other section 111. So industry is actually arguing at cross purposes in these two cases and depending on which way the court decides the mercury rule, it may defeat their argument in the challenge to the carbon rule.

CURWOOD: Sounds like a catch-22 to me.

PARENTEAU: Does sound like that doesn't it?

CURWOOD: Now what's going on here? I mean, why so many challenges from the coal industry all at once, and seemingly inconsistent challenges?

PARENTEAU: Well, I think the reason is because the law is finally catching up with the health effects and the environmental effects of coal-fired electricity, in fact, coal mining and coal use in general. And a number of rules have now been issued by EPA. There was the Cross State rule dealing with pollution that drifts over state borders and affects people downwind, there was the rule now setting limits on mercury, there was the proposed rule to set limits on carbon. EPA has tightened the smog rule, that's also going to be challenged. All of these rules are aimed squarely at coal, and all of them are saying that coal's effects have to be taken into account and have to be regulated, and that means that coal-fired generation in the United States is in serious trouble, and I think the industry is reflecting that they're under stress.

Patrick Parenteau is a Law Professor at Vermont Law School. (Photo: Vermont Law School)

CURWOOD: Some would say that the days of the coal industry and particularly coal-fired power plants are numbered in America. To what extent do you think that this lawsuit and some of the others are part of a rear guard action, you know, desperation plays?

PARENTEAU: It does look that way. The coal industry's enjoyed a lot of benefits and a lot of exemptions from strict environmental regulation, and those days are over and I think it's fair to say that coal's days are numbered, at least as far as generating electricity. You see natural gas coming online much more quickly, you see renewable energy sources expanding, you see energy efficiency improvements being made and all of that spells bad news for the coal industry in the US.

CURWOOD: Pat Parenteau is a professor of environmental law at Vermont Law School. Thanks so much Pat.

PARENTEAU: You’re welcome, Steve.

Related links:

- The EPA’s Power Plant Mercury Rule

- Law Professor Pat Parenteau

Coal Baron Indicted in Mine Disaster

Don Blankenship, former CEO of Massey Energy. (Photo: Rainforest Action Network; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Well, if burning coal is bad for public health, mining it underground can cause serious illnesses like black lung, and it’s a dangerous profession. In 2010, the deadliest US mining accident in over four decades killed 29 workers in an explosion at the Upper Big Branch Mine in West Virginia. Don Blankenship, a prominent coal baron and the CEO of Massey Energy that owned the mine now faces criminal charges for an alleged conspiracy to evade federal mine regulations and mislead investors and regulators. Patrick McGinley, a law professor at West Virginia University was part of a state investigation into the accident, and he detailed the federal charges against Mr. Blankenship.

A tribute to the 29 miners who died in the Upper Big Branch Mine explosion in 2010. (Photo: Jamiev_03; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

MCGINLEY: The first conspiracy count accuses Mr. Blankenship of overseeing operations that put profits before miners' safety, and the indictment includes references to a paper trail of communications between Mr. Blankenship and mine officials at the Upper Big Branch Mine indicating that he was placing extraordinary pressure on the management there to produce coal and give short shrift to basic safety procedures. There's another count that alleges that Mr. Blankenship created an atmosphere and instructed the president of the Massey Energy subsidiary to carry out a policy of warning miners underground that federal inspectors were on their way to inspect the mine, and that type of warning is a felony under federal mine safety law.

CURWOOD: Why is that illegal?

MCGINLEY: If the mine is being operated in an unsafe manner and the law and regulations are not being complied with, then warning that the inspectors are on the way allows the foreman and the miners working there to correct those violations so they won't be cited and fined.

CURWOOD: What particular violations are alleged here that were being allegedly gamed by Mr. Blankenship under his orders?

Coal mining at Kayford Mountain, West Virginia. (Photo: Kate Wellington; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

MCGINLEY: The mine was being operated without regard to the requirement that adequate ventilation be afforded to miners working underground, and ventilation is known as the lifeline of a coal mine. Ventilation air blowing through the mine and exhausting, that carries out dangerous explosive cold dust and also explosive methane gas, and the indictment alleges that the company was not following those basic requirements and exposing coalminers to exactly what happened - a catastrophic event - which ultimately killed miners as far as a mile away from the point of ignition.

CURWOOD: How surprised were you by the decision to indict Mr. Blankenship?

MCGINLEY: I was surprised only insofar as there was a question whether there was the political will in the federal government to proceed with an indictment. I worked on the investigation of the Upper Big Branch Mine for more than a year for the Governor's independent investigation panel, and my view was that there was sufficient evidence to go much higher up the chain of management than the lower level Upper Big Branch employees who were previously indicted.

CURWOOD: You must have seen a lot of evidence investigating this for the governor of West Virginia, but what pieces of evidence did you find most compelling?

Members of Rainforest Action Network stand up and hold banners as Don Blankenship, CEO Massey Energy, addresses a luncheon at the National Press Club in Washington, DC on July 22, 2010. (Photo: Rainforest Action Network; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

MCGINLEY: Well, it was clear that Mr. Blankenship was receiving reports of production from the mine every 30 minutes by fax to his office and to his home. And there were men who worked at the mine who testified under oath in our investigation that their hands would shake when the phone rang from upper management asking about secession of production for safety reasons. The fact that the mine was not rock dusted, which means material being sprayed on the walls and the floor and the ribs of the mine to suppress coal dust which is very explosive. The evidence that very little attention was given to suppression of coal dust was shocking. And maybe the most interesting and disturbing part of the testimony I heard was that Massey energy purported to be following what they call an S1P2 process, Safety First and Production Second. Mr. Blankenship had testified before Congress that Massey's safety procedures were more stringent in more than 70 ways than federal law. That was clearly false and misleading and had been part of the Massey corporate mantra for a number of years preceding the explosion of the Upper Big Branch Mine.

Long wall coal mining is a dangerous profession, with a high rate of accidents and respiratory diseases. (Photo: Jan Truter; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, Professor, how have coal executives been treated in the past with accidents similar to this?

MCGINLEY: Well, there's never been a corporate CEO or a chairman criminally prosecuted. That's why this indictment of Mr. Blankenship is extraordinary, and, for many, unexpected because of the century-long history of failure to hold corporate officials responsible when a mine disaster has occurred.

CURWOOD: What kind of precedent could be set in terms of holding CEOs accountable for major disasters?

MCGINLEY: Well, the basic premise of criminal law is that it can be used as a deterrent, and if for a century, corporate officials presided over unsafe mining practices and got a free pass, then the law had no deterrent value. And hopefully this is a sign that history is past, in that corporate executives of coal companies will be held accountable if there's sufficient evidence to show their criminal culpability when miners are killed.

CURWOOD: Patrick McGinley is a Law Professor at West Virginia University. Thanks for taking time with us.

Memorial for the miners killed in the Upper Big Branch Mine explosion. (Photo: US Department of Labor)

MCGINLEY: Sure. It’s my pleasure.

CURWOOD: The federal judge recently imposed a total gag order in this case. Earlier, Mr. Blankenship’s lawyer assured reporters in West Virginia that his client is entirely innocent of the charges.

Related links:

- US DOJ indictment document of Don Blankenship

- Reuters opinion piece about the gag order imposed on the Blankenship case

- About Professor Patrick C. McGinley

[MUSIC: Squirrel nut zippers from “Put a Lid on it” from Hot]

Coming up...desperate measures to try to halt rhino poaching in South Africa for the Asian medicine trade. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Toufic Faroukh from “Land of milk and honey” from drab:zeen ]

Human Rights On the UN Climate Change Agenda

A Burundian countryside is deforested, some of which is farmed, but most is left barren. Forests help to sequester carbon from the atmosphere and provide (Photo: jane boles; Flickr CC BY NC-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. The latest meeting of United Nations climate negotiators, known as COP 20, the 20th Conference of the Parties, began the first of December in Lima, Peru, and it’s a key stepping stone on the path to a new global climate deal in Paris next year. There’s renewed optimism in the air, after the two mega-polluters, China and the US, agreed to substantial cuts in their emissions, and solid commitments of $10 billion have been made for the Green Climate Fund. And there’s a new commitment as well – to make human rights a guiding principle of any agreement, including green energy development, and forest protection programs like REDD. Marianne Lavelle is a Science Writer for The Daily Climate, and in two recent pieces she examined the issue of what’s being called “the Human Rights COP”. Welcome to Living on Earth, Marianne.

LAVELLE: Glad to be here, Steve.

CURWOOD: So, how are climate talks now getting interwoven with human rights issues?

LAVELLE: I think if you went a few years back, most of the discussion would be about emissions cuts and timetables and a whole lot of numbers, but as the years have gone on, the talk has been more about people really, about social justice and human rights. The poor countries and poor people around the world are most affected by climate change, but they are the people who have the least to do with carbon emissions overload that we now are facing.

CURWOOD: One of the things that was done way back in the climate negotiations, back in 2007, was to say that if we reduced deforestation and the degradation of forests, that it would help the climate situation since trees sequester carbon, but I gather that there are number of human rights issues that come up around the question of deforestation - REDD.

A hydropower dam in Brazil. Many hydropower projects in South America and poorer countries throughout the world are touted as a solution to climate change, providing “clean” energy, but often displace local peoples from their land and cause other human rights problems. (Photo: lynx81; Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

LAVELLE: Right. This was really thought of as a win-win solution because the richer nations could invest in projects to preserve forests in poorer nations, but it's not really preserving the forest as it is but putting up, say, palm oil plantations and that completely changes the forest and makes it very much a different place than it was for the people who were living there. Another thing that is happening is fortress conservation, where Kenya will come in and just evict people who are living in the forest from their homes and put up fences to protect the forest. Well, that is not a solution that really keeps social justice and human rights in mind. We have to come up with solutions, the advocates are saying, that really take into account the human beings who really are at the front line of protecting these forests.

CURWOOD: Of course, one of the goals of the international climate negotiations is to reduce emissions and people point to hydropower as a way to make electricity without putting carbon dioxide in the air, but of course there's controversy over that and I gather part of the controversy includes what happens to the poor people who get displaced when a dam gets put in.

LAVELLE: That's right. How are we carrying out these clean energy projects? Are we making sure that the people get just compensation for land that they're giving out for these projects? Are they part of the decision-making? Is there a process to really keep the rights of the people living on this land in account? There are big hydroelectric projects in Panama, for instance, where it's been very controversial because native residents are being displaced, and some of these projects have been stalled because of protests. And this is happening around the world.

CURWOOD: What do you make of UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon appointing Mary Robinson, the former President of Ireland, as his special envoy for climate change? She, of course, was the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights.

LAVELLE: Right, and she has actually taken it upon herself to make climate justice a real issue that people are talking about around the world. She has her own foundation that's dedicated to climate justice and it's just certain that she's going to be bringing all of these issues front and center. Right now, the draft climate treaty does have some language about respecting human rights, but folks like Mary Robinson and feel it does not go far enough. That's something that should be integrated into all actions on climate change.

Marianne Lavelle is a science writer for The Daily Climate.

CURWOOD: So, how do you think addressing human rights affects the urgency addressing the overall issue of climate change?

LAVELLE: The human rights issue has the potential to slow things down even further. I don't think there's any question that in a way it has already because really what's held up these negotiations for so many years is the rift between rich and poor nations, and who is willing to put in their fair share and what is a fair share, and that really has stymied the negotiations all along. The social justice and human rights issues...they’re there whether we make it explicit or not. What Mary Robinson and others are saying is let's just put it right out there on the table and let's be clear that this is what we're talking about.

CURWOOD: Marianne Lavelle is a Science Writer for The Daily Climate. Thanks for taking this time with us today.

LAVELLE: Glad to do it.

Related links:

- Lavelle’s story “As climate talks open, human rights issues take the spotlight”

- Lavelle on how “Social injustice dogs two promising climate solutions”

- The UN’s Green Climate Fund

- The Harvard Project on Climate Agreement’s paper

- More about Marianne Lavelle

[MUSIC: Thomas Newman “Weirdest home videos” from American Beauty Soundtrack]

Rhinos For Sale

Poaching for rhino’s horns has left the species on the brink of extinction. (Photo: brainstorm1984; Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now few people could say that rhinos are cuddly, but they are a majestic keystone species of the African savannah. They are also severely threatened by the demand for rhinoceros horn from wealthy consumers in Asia, and their numbers are now reduced to a mere 25,000. Over 85 percent of the world’s rhinos live in South Africa, mostly in game parks – but that does not necessarily protect them; Kruger National Park, South Africa’s largest reserve, has lost nearly 600 rhinos this year to poachers. Park officials have considered many schemes to protect the rhinos: from poisoning the horns to humanely removing them, and now the park is selling off some of its rhinos in the hope of protecting them. Bobby Bascomb reports from Pilanesberg National Park in South Africa.

[DRIVING SOUNDS ON BUMPY ROAD, RADIO IN BACKGROUND]

There are only 25,000 rhinos left in the world, most of which live in South Africa. (Photo: Dion Hinchcliffe; Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

BASCOMB: A red dirt path cuts through the savannah of the Black Rhino Game Reserve in South Africa’s Pilanesberg National Park. Michael Joubert, Co-owner of the reserve, bumps along in the back of a safari truck and points across a wide expanse of knee-high dried grass towards the anti-poaching unit charged with protecting the conservation land’s rhinos.

JOUBERT: Right on that hill about half a kilometer in front of us on the right, that’s usually where they are stationed. They always try to find the highest place in the reserve and then they’ll change their sort of patrol tracks because they don’t want any kind of routine because then it can be learned.

BASCOMB: The anti-poaching units are similar to military personnel and the job is just as dangerous.

JOUBERT: These guys, when they come on they’ve got snipers and they’ve got AK47s and they have weapons that can’t match what the anti-poaching guys have. It’s almost like an unprotected war zone.

BASCOMB: Black Rhino Game Reserve lost three rhinos to poaching this year, all of them within 100 meters of the road. It’s a dangerous place for rhinos and the people protecting them but it’s still far safer than the country’s largest park, Kruger National Park. Roughly 530 kilometers east of Pilanesberg, Kruger is home to more than 8000 rhinos, the single largest population in the world. But they are losing them at an unsustainable rate - between one and two a day are killed by poachers. Now the park is trying to sell off some of its rhinos to places like Black Rhino Game Reserve in the hope that they might find safer sanctuary. Howard Hendricks, from the South African National Parks conservation services explains.

Poachers tranquilized a pregnant black rhino and removed her horn. In order to do so, they cut into her skull and then left her to bleed to death. (Photo: Sokwanele-Zimbabwe; Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

HENDRICKS: Our translocation program is aimed at translocating rhinos from hotspots - poaching hotspots - to areas of high levels of security.

BASCOMB: Kruger Park is a poaching hotspot for several reasons. First, it’s huge - more than 19,000 square kilometers, about the size of the country of Wales, and difficult to manage.

[RANGER TALKING ON THE RADIO]

An even bigger problem though is the long porous border Kruger shares with neighboring Mozambique. Until recently, the penalty for poaching in Mozambique was a small fine that rarely got paid. As a result, Hendricks says roughly 80 to 90 percent of poachers in Kruger Park are from Mozambique, one of the poorest countries in the world.

HENDRICKS: Poaching takes advantage of the high level of poverty around Kruger. Poaching is a problem simply because there’s high monetary values involved. If someone is poor then obviously it’s an easy access to money.

South Africa’s Kruger National Park hosts many varieties of species, including elephants, rhinos and impala. (Photo: Jeppestown; Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

BASCOMB: It’s estimated that rhino horn is worth more than 1 million Rand, or $90,000 per kilo - although it’s difficult to confirm that figure. It is the black market after all and conservation groups don’t like to advertise its value, fearing it will spur more interest in poaching. In any case, poaching is a high-stakes multi-billion dollar industry. Again, Michael Joubert from Black Rhino Game Reserve.

JOUBERT: Per kilo it’s worth more than cocaine, gold, platinum, anything like that. It’s run professionally by crime organizations, similar to a drug cartel or anything.

BASCOMB: Earlier this year a ranger and two staff at Kruger Park were arrested for rhino poaching. One rhino horn could be worth nearly a lifetime in wages for anti-poaching units.

JOUBERT: The heartbreaking reality is they aren’t paid well at all. Just as police and law enforcement and teachers and stuff - these jobs that should have a high paying salary the truth is they don’t.

BASCOMB: Joubert says the trick is to hire guards that genuinely care about the animals and feel passionate about protecting them. Rhino horn can be humanely removed without hurting the animals, much like cutting your fingernails. But the thickest, widest part of the horn is embedded in the rhino’s skull.

JOUBERT: They want every gram of the horn. They’ll actually saw into the skull. And they don’t kill the rhino beforehand, they tranquilize them first so the rhino goes to sleep, they remove the horn, then the rhino eventually wakes up traumatized...it’s got this massive hole in its skull and then it actually bleeds to death. So it’s just so sad.

[MUSIC]

In some of the world’s poorest countries poaching and selling rhino horns on the black market is big business. (Photo: alcuin lai; Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

BASCOMB: Rhinos are in a sad state today and scientists worry that the number of rhinos being killed will soon exceed the number being born, threatening the species with extinction in the coming decades. But Jo Shaw, manager of the rhino program for World Wildlife Fund in South Africa, says the sale and translocation of rhinos being proposed has a proven track record for protecting the animals.

SHAW: At the turn of the 19th century there were only maybe 50 Southern White Rhinos left in the world in just one park in South Africa. And it was the movement of these animals to new areas like Kruger Park that grew the numbers that we see today. So, including this strategy to combat rhino poaching is actually really a tried and tested approach to combating this kind of threat.

BASCOMB: Kruger Park officials are still working out the details of their translocation sale, but observers like World Wildlife Fund are hopeful that moving some rhinos from poaching hotspots will be a step in the right direction towards saving one of Africa’s most iconic species.

Bobby Bascomb, Pilanesberg National Park, South Africa.

CURWOOD: That report came to us from Radio Deutsche Welle.

Related links:

- Pilanesberg National Park and the Black Rhino Game Reserve

- Kruger National Park

- More on Africa’s Rhino poaching crisis

Place Where You Live: Gaborone, Botswana

A water pipe burst and flooded Karin Vermilye’s yard in Gaborone, Botswana. (Photo: Courtesy of Karin Vermilye)

CURWOOD: And we stay in Southern Africa for another installment in the occasional Living on Earth/Orion Magazine series “The Place Where You Live.” Orion invites readers to put their homes on a map and submit essays to the magazine’s website, and we’re giving them a voice.

[MUSIC: Edward Sharpe and The Magnetic Zeroes “Home” from Edward Sharpe and The Magnetic Zeroes (Rough Trade Records 2009)]

Your special place doesn’t have to be exotic, but it certainly is for Karin Vermilye.

Vermilye and her daughter watch a giraffe at a game reserve nearby. (Photo: Courtesy of Karin Vermilye)

VERMILYE: I’m from Gaborone, Botswana, that’s the place where I live. So it's near South Africa and Namibia is in the north and Zimbabwe is right there too and Zambia and there's lots of wildlife all around. There's lots of people and it's lively, but it's also quiet. It’s nice for our family. We have two kids and we like to take them out on game drives right outside the city. There's a game park, a few of them actually, not far from here. We love that we can take our young kids and go see zebras and warthogs and ostrich and giraffe just on a weekend or some day after school.

CURWOOD: Here’s Karin’s essay.

[CREAKING DOOR OPENS]

VERMILYE: The water pipe outside our gate burst early one morning. It was a warm night in Gaborone, Botswana, a place I’d called home for two years. A new river bubbled up from the jagged hole in the ground and ran over the gate and into our thirsty yard. My mind was on mosquitoes that, I imagined, would now swarm to this wet oasis. Gaborone is only a few hours away from the Kalahari desert, whose name comes from the Setswana word “kgala” meaning “great thirst”, and Botswana struggles to meet the water demands of its growing population. A few weeks before, I had read another notice on water restrictions and the dropping level of water in the dams. We were urged not to use drinking water for gardens. Therefore, our yard was thirsty. The grass, long past any color close to green, had become a brown akin to the dust that sometimes swirled up around our car as we drove through the nearby game park searching for zebra and giraffe.

Karin Vermilye at a game park near her home in Gaborone, Botswana. (Photo: Courtesy of Karin Vermilye)

The water was finally turned off by Water Utilities at the main line, and the river turned to a trickle, and then stopped. My neighbor had come to help sweep some of the water away from the yard back into the street. The ground by the gate had softened as the water filled every crack in the soil, and it suddenly opened up to swallow her. She quickly put her arms out and stopped her fall into the muddy watery cavern that appeared so swiftly below her feet. We pulled her shaking and wet from the hole, laughing a laugh of what could have been, but did not come to be.

I told her my worries of the mosquitoes, as we sloshed through the water now up to our calves. She shook her head and said it would not be a problem. By noon, all the water was gone. Drunk up by the parched soil. A few days later our yard turned back to green.

CURWOOD: In the Setswana language, “pula” the word for “rain”, also means money – a mark of how scarce and valuable water can be in this parched land.

Plump lemons grow on a tree in Vermilye’s garden. (Photo: Courtesy of Karen Vermilye)

VERMILYE: For many months, it was very dry and so what we would do is save our bathwater and take that outside and water our plants with that. The rains just came and so you can just see that things are starting to come back now. The flowers are starting to come out and some of the plants are trying to peek their heads up from the ground and things like that. We have a lemon tree, and all the lemons are still green from the tree, but they are starting to turn a little bit yellow, so they should be ready in another few weeks, and there's some small little orange trees and a grapefruit tree, but those have not been very big this year because of the lack of water.

CURWOOD: That’s Karin Vermilye, from Gabarone, Botswana – and you can tell us about the place where you live if you like. There’s more about Orion Magazine and how to submit your essay at LOE.org.

Related links:

- How to contribute to Orion Magazine’s The Place Where You Live

- Orion Magazine

- Past editions of “The Place Where You Live” on Living on Earth

[MUSIC: Wilco from “Sky Blue Sky” from Sky Blue Sky]

Coming up...a message of hope on global warming despite the peril the planet faces.

That's just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems, provides building technologies and supplies container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Wynton Marsalis from “Cottontail” from Live In Swing City]

Beyond the Headlines

In the 1980s, a flurry of reporting on the potential link between high-voltage power lines and cancer created an atmosphere of fear that persists today, despite the lack of evidence linking the two. (Photo: Hope Abrams, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Time to take a trip to Conyers, Georgia, for a look beyond the headlines. Our guide as usual is Peter Dykstra. He publishes Environmental Health News, EHN.org and the DailyClimate.org, and he's on the line now. What’s on tap today, Peter?

DYKSTRA: Well, I'm all about history this week Steve, but let's start with a story that a lot of folks may have gotten wrong. A New York Times feature called the Retro Report tracked this one down. Back in the 1980s there was a flurry of reporting, and a frenzy of activism, over the potential cancer risk from radiation coming from high-voltage power lines.

CURWOOD: Now, there actually were studies that said there's a possible link between electromagnetic radiation from powerlines and leukemia, right?

DYKSTRA: Right, back in 1979, there was indeed such a study suggesting a link as well as another big study in 1987, but in the years since, many subsequent papers haven't really built on those findings, and speaking in epidemiological terms, 35 years is plenty of time to establish health patterns. A few scientists still continue to research the link, while some others say there's little chance at this point that radiation from powerlines is a human health threat.

CURWOOD: So if the research hasn't come in to back up the original concerns, are we mostly dealing with a fear factor here?

Frances Oldham Kelsey, who recently celebrated her 100th birthday, withheld approval of thalidomide for use in the U.S. In 1962, President Kennedy awarded Kelsey the President's Award for Distinguished Federal Civilian Service for her refusal to cave to the pharmacological industry’s pressure. (Photo: Luciana Christante, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Possibly. Some folks in the media have been known to play up scary things, and this one has all the ingredients: fear of cancer, particularly in kids, a risk we can’t control. There might be other reasons to be concerned about powerlines: in many parts of the country, rights-of-way for powerlines are still maintained by applying a healthy dose of pesticides, and also, huge steel towers and cables galloping through the countryside are just plain butt-ugly. That last one isn't peer-reviewed, but it seems to be a universal feeling. Bottom line: after 35 years of scrutiny and study, there's still no smoking gun to show a significant health threat exists from powerlines.

CURWOOD: And the other bottom line is that most environmental science gets validated over time, but not all, or at least so far. What's next?

DYKSTRA: A story from the Globe and Mail in Canada about a true science hero. Frances Oldham Kelsey is a hundred years old now but in 1960, she was a mid-level bureaucrat at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. If you were born in the US in the early '60s, Frances Kelsey may very well have saved your life.

CURWOOD: I think you may have just gotten some people's attention.

DYKSTRA: Yeah. Thalidomide was a wonder drug widely used in Europe and Canada in the late 1950s. It was prescribed as a sedative, and for pregnant women, it made morning sickness go away. There was a clamor to approve thalidomide for use in the U.S. and all that stood in the way of FDA approval was the sign off from medical officer Frances Kelsey. She had some serious questions about side effects from the drug, and despite relentless pressure from the manufacturer, she stood her ground until those questions were answered.

CURWOOD: And anyone who knows the history of thalidomide knows that those answers came in the form of a health disaster.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, in the countries where thalidomide was rushed to the market, it's blamed for thousands of deaths or serious deformities in the children of the pregnant women who took it. The US escaped the disaster, all because one government worker stood up to pressure and put health and safety first.

CURWOOD: Ah, so it's possible to be a government bureaucrat and a hero at the same time, huh? Now, what do you have on the history calendar this week?

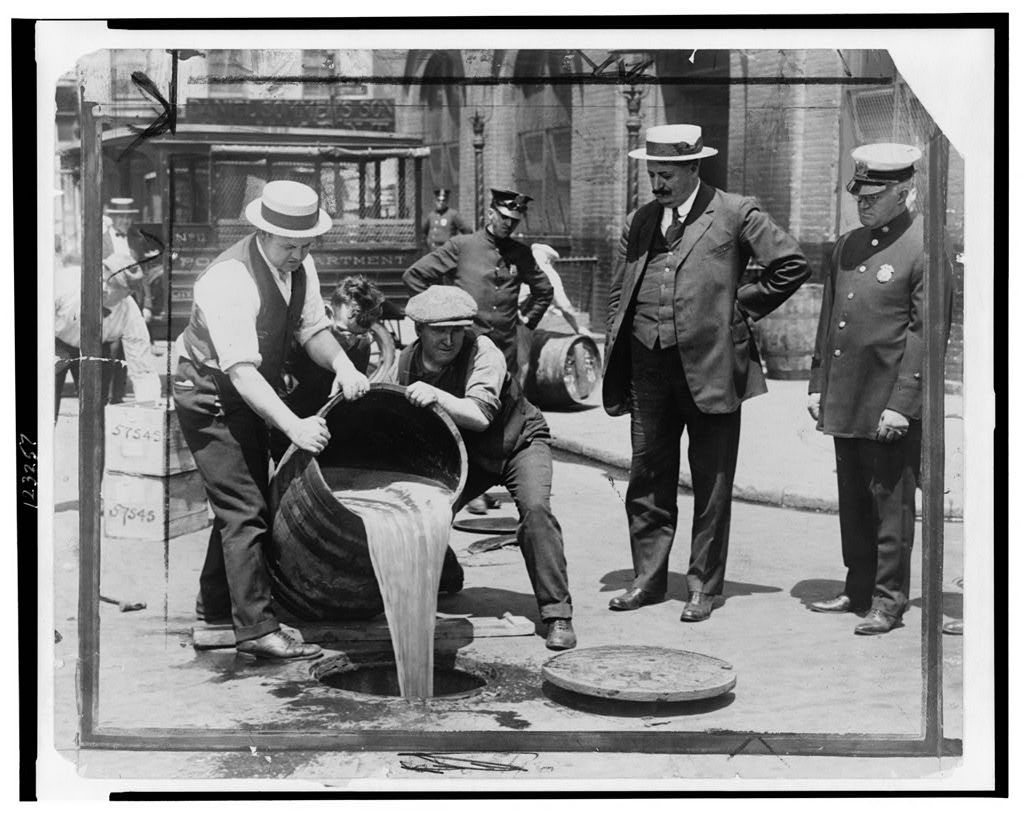

Since ethanol was banned during the Prohibition era, engineers designed motors to be gasoline powered. Subsequent models built upon these, causing lasting consequences for the U.S. energy infrastructure. (Photo: Dewar’s Repeal, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Eighty-one years ago this week, Prohibition was repealed, and America could legally drink once again, not that that many people had been deterred by the law in the first place. But Steve, the end of Prohibition had a huge environment and energy angle as well. Alcohol for drinking was still made, and sold, and smuggled throughout the Prohibition era and it helped build the Mafia and gangsters and all sorts of TV shows and movies, but when the making of alcohol was banned, ethanol for fuel was effectively outlawed as well because ethanol, most commonly made from corn these days, is essentially alcohol.

CURWOOD: Which in turn, put gasoline in the driver’s seat as the fuel of choice for cars.

DYKSTRA: Well, it didn't literally put gasoline in the driver’s seat, I believe that's still illegal, but yeah. Two titans of the early 20th century took opposite sides on Prohibition. Henry Ford was opposed because his iconic Model T cars were designed to run on ethanol. John D. Rockefeller and his oil business viewed ethanol as his main competition, so he was very pleased to see it outlawed.

CURWOOD: And only in recent years has ethanol recovered, but then again, corn-based ethanol has more than its share of critics today, right?

DYKSTRA: Pretty much. It made something of a comeback on both sides in World War II, when oil and gasoline were in short supply. The Germans actually fueled their V-2 rockets with ethanol. Renewable energy standards today give us a blend of ethanol and gasoline. The corn belt loves ethanol, Presidential candidates praise it while passing through Iowa, but its pollution burden and its real value are subjects of debate. But Prohibition and its ban of ethanol from 1919 to 1933 tipped the scales in favor of gasoline, and it changed the course of history.

CURWOOD: Well, thank you, Peter. Peter Dykstra is the publisher of Enviromental Health News – that's EHN.org and the DailyClimate.org. Talk to you soon!

DYKSTRA: Alright, Steve, talk to you soon!

CURWOOD: And there's more at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- The fear of power lines’ link to cancer, as report by the New York Times

- How Frances Oldham Kelsey kept thalidomide out of the U.S.

[MUSIC: KGFREEZE from “Grace” from VOLUNTEER]

Beinecke's Message of Hope for a Planet In Peril

Frances Beinecke has served as NRDC’s president since 2006. (Photo: ©Joshua Paul/NRDC)

CURWOOD: For 40 years, Frances Beinecke has been involved with the urgent need to protect our environment. She first worked as an intern at the Natural Resources Defense Council back when it was getting started…and stayed. For the past eight years she's been NRDC's President and for eight years before that she was executive director. Now, she's stepping down and has written “The World We Create”, a book subtitled “A Message of Hope for a Planet in Peril.” Welcome to Living on Earth, Frances.

BEINECKE: Well thank you, Steve, it's so great to be here.

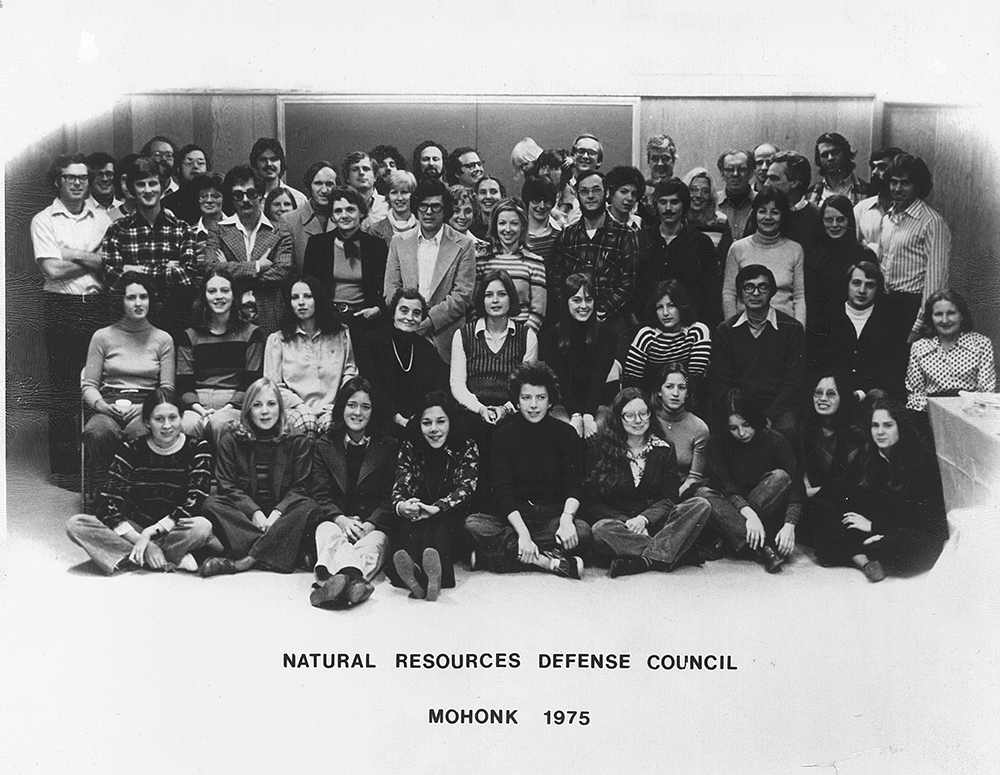

Frances Beinecke joined the NRDC as an intern in 1973. She is shown here in a staff photo taken five years after the organization’s founding, in the 2nd row, 1st on the left. (Photo: courtesy of NRDC)

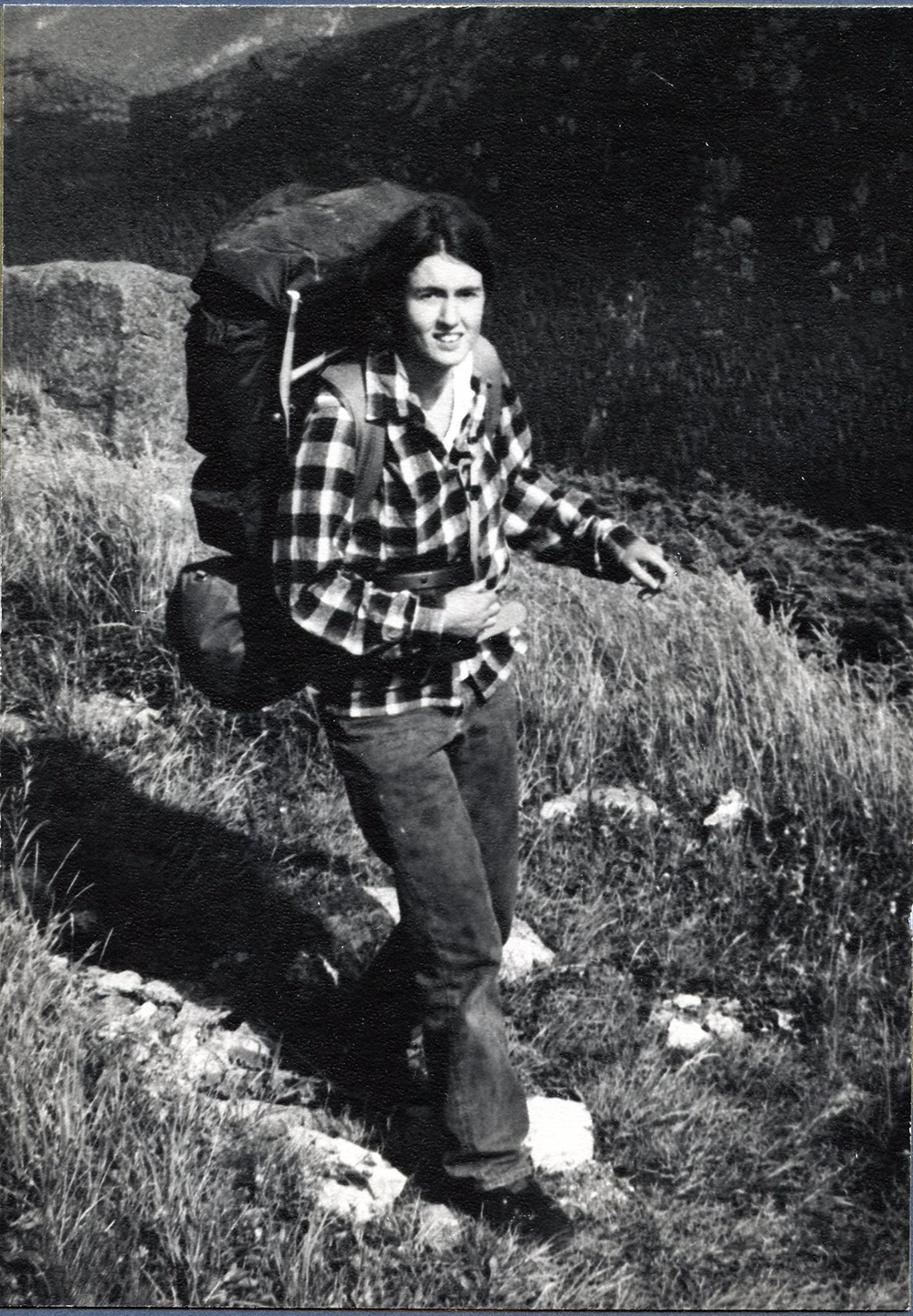

CURWOOD: Well, let's go back. Your early life gave you a love of nature and the US landscape, a house in the Adirondacks; your father taught you to fish, you were a keen hiker.

BEINECKE: You know, I was able to see a lot of the American landscape when I was very young, which really caught my attention, and really I think created a passion, and then when I was in college and later on I became a very avid hiker and a lover of nature, so it sort of came on throughout my childhood.

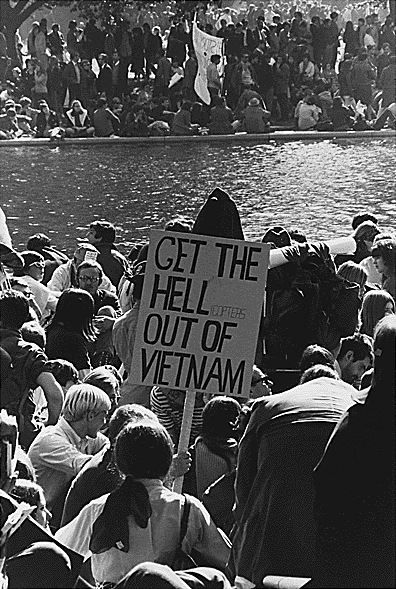

CURWOOD: So you were a student back in the 60s and 70s. It was exciting times for the environmental movement: Earth Day, new laws for clean air and water, and a great time for activism. How did that affect you?

After BP’s Deepwater Horizon oil spill, also known as the Macondo blowout, President Obama appointed Beinecke to the National Commission on the BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill and Offshore Drilling. (Photo: SkyTruth; Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

BEINECKE: It really affected me very, very significantly. So when I got to college in 1968, that was really at the beginning of the very strong anti-war movement and I was swept up in that. We went to Washington, we joined marches, we were on strike at our universities. I think that for me, that really formed my commitment to social change and to civic engagement.

CURWOOD: Given the current climate crisis, how much of the spirit of the ’60s and ’70s do we need today, do you think?

BEINECKE: Well, first of all, we really need it, and the thing I'm really heartened by is it's coming back. People are both rising up, they're raising their voices, and they're also looking at what are the alternatives, what are the clean energy pathways that we need to go down?

CURWOOD: You were, of course, a member of the president's commission on the BP Macondo well disaster. The commission's final report was critical of just about everybody involved in that. What's your biggest takeaway from that experience, looking at how the fossil fuel industry conducts itself?

BEINECKE: Well, my biggest takeaway, which was not new, but it was a potent reminder of how immensely powerful the oil industry is. It was a reminder that they basically own the game, and if we don't have the system of laws and oversight and enforcement of the environment, the public wellbeing and the economy of people who are living near their operations are at risk. It just doubled my resolve to ensure that we have a system of safeguards.

Beinecke’s involvement in environmental activism was seeded in part by her participation in Vietnam War protests. (Photo: Frank Wolfe, Wikimedia Commons CC)

CURWOOD: Now, for a number of years NRDC, the organization that you're the retiring president of, was at the forefront and try to get a cap-and-trade through Capitol Hill. It didn't work. What do you think went wrong and what you think needs to be done now?

BEINECKE: It didn't pass for a lot of reasons, I think first and foremost it was the downturn in the economy that really made it very difficult to get something as sweeping as that passed. But one thing coming out of that was it did not alter our resolve at all because climate is such an important and urgent matter. It really made us double down and look seriously at what are the strategies that we needed, where did need to make the investment to really build the public case and support for action on climate, and now what we're focused on is using the authority of the Clean Air Act under the executive authority of the president to get at our largest source of emissions, which is our power plants across the country, and that's something that you know we hope and we're working hard to achieve in the next two years: adoption of these carbon pollution standards under the Clean Air Act.

Beinecke cites the UN People’s Climate March in New York City, which drew a crowd of more than 400,000, as a hopeful sign of citizens’ engagement in climate issues. (Photo: Stephen Melkisethian, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: How fair is it to say that the failure of that cap and trade legislation is a sign that the fossil fuel industry is simply not willing to come half the distance with people who are concerned about climate, that it's their way or the highway?

BEINECKE: The industry, fossil fuel industry, has a great deal of money, they have a lot of power, but what we have are large numbers of people and a democracy that is engaged in the issue. And I think what we have to do is really to ensure that voices and numbers of people are raised for a different pathway.

CURWOOD: So the recent election brought gains for the Republicans. It doesn't look like there's much likelihood of congressional action to take on fossil fuels over the next couple of years, and the new likely Majority Senate Leader, Kentucky's Mitch McConnell, has made it a new top priority to approve, what, the Keystone XL pipeline and defund any carbon controlling measures by the EPA. What's your view?

While in college at Yale, Beinecke enjoyed connecting with nature while backpacking. (Photo: Courtesy of NRDC)

BEINECKE: So that is absolutely not what our agenda is, we think it's imperative to act on climate, to reduce emissions, to use the Clean Air Act authority which was upheld by the Supreme Court three times. We realize this is going to be a fight with the Congress and you know that's a fight we're prepared to undertake. We also believe that the President is deeply committed to putting these standards in place and will do everything within his power to ensure they are adopted. This will not be an easy path over the next two years, but it's certainly a path we're going down.

CURWOOD: What kind of backbone rating on climate change would you give the President of the United States? Mr. Obama's first four years there was really not much of a mention about climate. Yes, we did have vehicle emissions standards, mileage standards come forward but he didn't really get up on the bully pulpit until after he was re-elected. How strong is he really on this issue?

BEINECKE: Well, Steve, I think that the President is very strong on the need to act on climate. On June 25, 2013, when he made his speech at Georgetown and really kind of laid the template down for what his climate strategy was going to be, it was very comprehensive. I mean, it included the carbon pollution standards, but it really directed every agency in the federal government to have a very active climate agenda and figure out and take action on what they could do to reduce emissions and move us down a clean energy pathway. He really understands and sees what the long-term threat is to the country and to the planet, and, you know, I think the the US actually is in a very strong position through the fuel efficiency standards that he adopted in the first term to these carbon pollution standards for the power sector to put the US in a leadership position worldwide. You know as you know, the world leaders are going to gather in Paris in 2015 to again reach agreement on how to reduce our emissions from climate change, and I think the US will be going into those conversations from a very strong place.

Young Frances Beinecke hikes in Wyoming’s Grand Teton National Park. (Photo: Courtesy of NRDC)

CURWOOD: So since those days where you were an intern and you guys were wondering maybe when the next rent check would come from, NRDC has grown and developed beyond all recognition. What do you think is the most important focus for the NRDC today?

BEINECKE: Well, first of all, NRDC is 43 years old, and we now have 500 people and seven offices, we’re a very large place, but we still have our primary commitment, which is to safeguard the Earth and ensure that all people have a system of environmental protection. Climate change is the very urgent threat that we face every day. We have as many as probably 100 people on NRDC staff working at one aspect or another of curbing emissions and unleashing clean energy and people in our oceans program, our land program, our public health program are working on all aspects of this very serious threat, and are very focused on what are the solutions we have to put in place as well as making sure that people are aware of how very urgent this threat is.

In 2009, the NRDC joined more than 60 organizations to form the Clean Energy Works coalition, advocating “unleashing clean energy” as a strategy for mitigating the climate crisis. (Photo: Courtesy of NRDC)

CURWOOD: The subtitle of your book, Frances, is "A Message of Hope". Now, of course, we're looking at the latest UN reports that paint a fairly dire portrait of the state of the planet and the climate. Where is it that you find hope?

BEINECKE: Well, where I find hope, Steve, is in the engagement of people. Just looking at the last three years, the number of people who are now understanding what the consequences of fossil fuel development is to them and wanting to go down a different pathway, whether it's the frackivists in New York where are very loud and determined not to allow fracking here, to the farmers in Nebraska who live along the Keystone pipeline, to the people all across the gulf whose businesses, whether the fishing industry or the tourism industry or even the oil industry, were put out of business because of the Macondo disaster. One of the most heartening things to me was the climate march in New York City in September where over 400,000 people joined together to demand climate action. And those 400,000 people were just a tip of an iceberg that's growing across the country of people demanding action on clean energy and, at the same time, there is a tremendous amount of clean energy being developed around the country. There's wind farms, solar arrays, in state after state after state, and there are people who are employed in those industries, who are making money in those industries who see this as a huge opportunity for the country, so it's both in the voices raised and in the economic opportunity that's been created that I see hope.

CURWOOD: Frances Beinecke is the retiring President of the Natural Resources Defense Council and the author of the new book "The World We Create: A Message of Hope for a Planet in Peril”. Frances, thanks for taking the time today.

BEINECKE: Thanks, Steve, it's a pleasure to be here.

Frances Beinecke retires after more than forty years at the NRDC. (Photo: Courtesy of NRDC)

Related links:

- Frances Beinecke’s NRDC blog about her book, The World We Create

- Natural Resources Defense Council

[MUSIC: Radiohead from “Bloom” from The King of Limbs]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jenni Doering, Lauren Hinkel, Jake Lucas, and Jennifer Marquis are all part of our team. Our show was engineered by James Curwood, with help from Karlyn Daigle. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us on our Facebook page - it's PRI's Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more. www.stonyfield.com.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth