Turtle Rescue

Air Date: Week of December 19, 2014

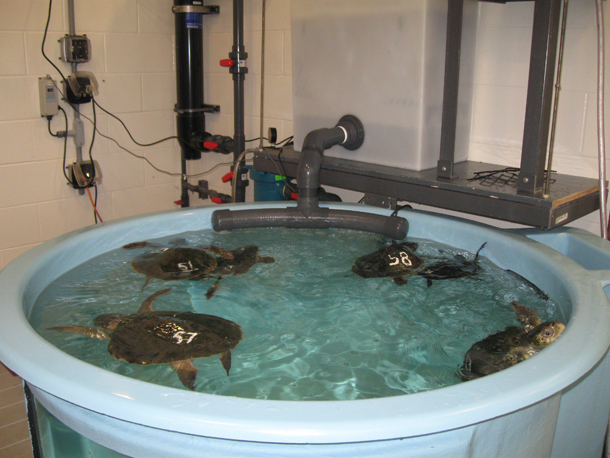

Tanks filled with turtles at the New England Aquarium’s Animal Care Center (Photo: New England Aquarium)

Every fall, hundreds of frigid sea turtles wash up on Cape Cod beaches, victims of geography, winds and cold water. This year record numbers of turtles have been stranded, though scientists aren’t sure why. Thanks to volunteers at the Massachusetts Audubon society and the New England Aquarium, many endangered turtles will be rescued, rehabilitated, and released. Living on Earth’s Emmett FitzGerald reports.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s far too cold to swim in the waters off New England at the moment. But as winter comes on, chilly water regularly brings some special guests onto the beaches inside the arm of Cape Cod. Every year, sea turtles caught in the cold begin washing up on shore.

LECASSE: The north side of Cape Cod is formed like a big bucket. Turtles, when they get the instinct to swim south in the early autumn, that instinct is blocked by all this land.

CURWOOD: That’s Tony LeCasse of the New England Aquarium. For the past twenty years, the aquarium has been partnering with the Audubon Society to rescue turtles who become too cold and get stranded on the beach. Two years ago there were a record number, 242 of them, as Living on Earth's Emmett FitzGerald reported.

[Beach sounds]

FITZGERALD: Each year in November, dozens of volunteers pull on hats, zip up their parkas, and tramp the beaches of Cape Cod from Sandwich to Truro. They head out just after high tide, sometimes in the dark, following the wrackline, where seaweed marks the water’s highest point. These hardy beachcombers are looking for turtles.

LACH: We are watching for that familiar sea turtle shape, about the size of a dinner plate, but with flippers.

FITZGERALD: Michael Lach and his nine-year-old son Skyler have been volunteering with the Massachusetts Audubon Society for four years now.

Volunteer Skyler Lach, age 5, handing hypothermic turtles on the beach in Cape Cod in 2008 (photo: Michael Lach)

LACH: We asked if we could volunteer for their sea turtle rescue program and we were assigned to this very beach, Linnell Landing Beach, the next day. And what happened the next day? Who found the first turtle?

SKYLER: I did.

LACH: You did that’s right. I was really excited when we found that first one.

FITZGERALD: They comb the beach in the evening, after Skyler gets out of school. When they spot a turtle, they set it above the tide line for the Audubon staff to collect.

SKYLER: You try to find a marking, so that Audubon can see it better.

LACH: Something that really stands on the beach so that when Audubon comes down to the beach to find and pick it up they can locate it easily.

FITZGERALD: This year there have been more stranded turtles than ever before, but Skyler has only found a couple, and he's looking to add to his total.

LACH: The most we’ve found in one year is six and we’re trying to beat that record. We’ve still got five more numbers to go because we’ve already found two. If we added our last three years up I’d say that’s about 14.

[Beach sounds]

FITZGERALD: Bundled up and armed with flashlights, Skyler and his dad head off into the night.

SKYLER: Do you think we’re going to find any today?

LACH: I don’t know; we still have quite a bit of beach to walk. I think we have a pretty good chance of finding one because the northwest wind, that’s the best wind for it, but the wrackline is a bit thin.

FITZGERALD: Massachusetts Audubon delivers all of the turtles that volunteers find to the New England Aquarium’s Animal Care Center in Quincy, Massachusetts.

Numbered turtles swim in a small tank at the Animal Care Center in Quincy (photo: Michael Lach)

[Train]

FITZGERALD: The Animal Care Center is in an old brick building along the Quincy wharf. Freight trains wind between abandoned warehouses with smashed windows, and the smell of the sea is thick. Tony Lecasse let me into the Center.

[Door]

FITZGERALD: Inside the cavernous room are massive circular tanks like aboveground swimming pools. They are filled with threatened sea turtles—spotted Greens, large Loggerheads, and the most endangered sea turtle in the world, the Kemp’s Ridley.

LECASSE: The predominate species and the most important one is these little Kemp’s Ridleys. They are everywhere from dinner plate size to platter size. The juvenile sea turtles are a charcoal black with a white serrated edge and they sort of have a heart-shaped shell.

FITZGERALD: As I peer over the edge of the tank, a turtle comes up for air.

[breath noise]

FITZGERALD: Tony says, don't get too close.

A stunned loggerhead turtle being loaded into a plane bound for Georgia (Photo: New England Aquarium)

LECASSE: They’re cute little guys but you still gotta be careful with them. These guys primarily eat crabs, so if you stuck your finger in there, you might require some good stitches.

FITZGERALD: Every day, the Audubon Society delivers batches of turtles to the center in Quincy.

LECASSE: We had three days last week where we had more than 20 turtles come in at a time. To give you an idea of how unusual that is, sea turtle hospitals in Florida, might see 20 sea turtles in a season.

FITZGERALD: This hospital can hold about 100 turtles at a time. If they get more than that, they have to offload them to other facilities up and down the east coast. The center recently sent 35 turtles to Florida in a Coastguard plane. Tony says that scientists at the aquarium aren’t sure why so many turtles have stranded this year. It could be good news: the total population of turtles is recovering, and the number of hypothermic turtles is rising along with it. But climate change could be playing a role as well. Tony thinks that warm water temperatures last year might have confused the turtles, delaying their normal migration.

LECASSE: In 2011, we had water temperatures that were five and six degrees above normal for a good part of the year. And so the normal environmental cuing didn’t happen because the water was warm, and they probably thought they had more time.

FITZGERALD: When the turtles arrive at Quincy, they’re usually in pretty bad shape. They have often been floating in the bay for months, and have used up all of their fat reserves.

LECASSE: Normally there should be big rolls of fat like you’d see on a 12-month-old baby coming off the thighs. But what will happen is that you will literally see a skinny leg with sort of draped skin over it, and that just indicates how dehydrated and how emaciated a lot of these turtles are.

FITZGERALD: First the hospital staff treat each turtle for hypothermia and dehydration. Unlike warm-blooded animals, these reptiles need to be rewarmed gradually, about five degrees a day, to prevent infections. Once a turtle is back on its flippers, it can be moved into one of the big tanks with the others. The staff paint a number on the back of every turtle’s shell with white nail polish, so they can keep track of each individual.

One of the biggest challenges can be feeding.

Head veterinarian Charles Ennis treats a loggerhead at the turtle hospital in Quincy (Photo: New England Aquarium)

LECASSE: My job right now is to focus on number 28, he’s not eating.

FITZGERALD: Carla is a volunteer at the turtle hospital. She’s dangling a piece of herring in front of a small turtle with a white number 28 scrawled on its shell. Despite her efforts, 28 isn’t interested in the food.

CARLA: What we’re doing for 28 is we’re actually tube feeding him, which we don’t like to do, it’s stressful for the animal. So that’s why I need to work on him for at least a half an hour.

FITZGERALD: Feeding the turtles is an exact science, and the staff carefully monitor each individual’s food intake.

CARLA: We feed them squid and herring, and everything is weighed so we know exactly how much they’re eating.

FITZGERALD: Recent arrivals often struggle to eat solid food, and as Carla tries to coax these reluctant newcomers, healthier veterans sometimes get in the way.

CARLA: See number 55 he’s obviously hungry. So you’re trying to feed number 93 but…yes number 55 is hungry but I bet he’s already reached his capacity.

FITZGERALD: Turtle rehabilitation takes a long time. Best-case scenario, a turtle will be out of the center in a couple of months, but some will require nearly a year of treatment. When the turtles are healthy, the aquarium transports them to warmer waters to be released.

LECASSE If the turtle is ready to go in early January or February, we’ll arrange for the turtle to be flown down to Florida or Southern Georgia to be released down there. If the turtle is ready in March or April, we’ll bring that turtle down to the Carolinas. If they’re ready in the summer time we’ll release them off of the Cape or off of Martha’s Vineyard.

Stunned loggerheads being transported from Cape Cod to Quincy (Photo: Michael Lach)

FITZGERALD: The New England Aquarium and Wellfleet Audubon have been rescuing turtles for 20 years now, and they’re proud of their record.

LECASSE: If a turtle arrives alive here, it has a 90% chance of surviving and being released.

FITZGERALD: That’s thanks to biologists, veterinarians, and hundreds of committed volunteers, young and old. In the past twenty years, they have rescued, rehabilitated and released over a thousand sea turtles. For these critically endangered creatures, every effort counts. For Living on Earth, I’m Emmett FitzGerald.

CURWOOD: That number of a thousand turtles that Emmett reported had been rescued and rehabilitated over 20 years has been blown out of the water by the tally for this year. Mass Audubon volunteers have collected over a thousand turtles on Cape Cod just this fall, and they still expect some larger sea turtles to become stranded on the beaches. According to the New England Aquarium, about 97% of them are endangered Kemp’s Ridleys and so far some 640 hypothermic turtles have been warmed, treated and flown south.

As to the causes of this year’s truly historic event, so far there are only guesses. But biologists are encouraged by seeing so many Kemp’s Ridleys, given their critically endangered status.

Links

New England Aquarium: Marine Animal Rescue Team Blog

Massachusetts Audubon info about sea turtles and their rescue

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth