December 19, 2014

Air Date: December 19, 2014

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

India Says UN Climate Summit Fails Poor Countries

View the page for this story

Earlier this month, for the first time, all 190 nations meeting in Lima Peru pledged to present actionable plans to cut CO2 emissions by early next year. But many feel that the landmark accord wasn’t strong enough. Host Steve Curwood discusses India’s need for cash for clean development, its role in UN climate negotiations, and how to share global warming’s burden fairly with Sunita Narain, Director General of India’s Centre for Science and the Environment. (11:05)

Giveaways Turn Appropriation Bills Into Christmas Trees

View the page for this story

As Congress rushed to get spending bills passed before lawmakers went home for the holidays, unrelated attached riders gave gifts to mining and fossil fuel companies. Host Steve Curwood points out that these can come at the expense of the environment and native Americans. (04:10)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s trip beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra tells host Steve Curwood about how time ran out for an oyster farm, the death of an iropneering environmental chemical watchdog, and a young activist who lived in a redwood tree. (04:45)

Turtle Rescue

/ Emmett FitzGeraldView the page for this story

Every fall, hundreds of frigid sea turtles wash up on Cape Cod beaches, victims of geography, winds and cold water. This year record numbers of turtles have been stranded, though scientists aren’t sure why. Thanks to volunteers at the Massachusetts Audubon society and the New England Aquarium, many endangered turtles will be rescued, rehabilitated, and released. Living on Earth’s Emmett FitzGerald reports. (08:15)

BirdNote® Freeway Hawks

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

North America’s bustling highways hardly seem an ideal habitat for wildlife, but the grassy medians teem with rodents and other small mammals, creating an ideal hunting ground for the Red-tailed Hawk. Mary McCann reports. (02:00)

Louisiana's Moon Shot

View the page for this story

The state of Louisiana is rapidly melting into the sea, and its sinking deltas threaten crucial US oil, gas and fishing industries. But Louisiana has a “Hail Mary” plan to save it. ProPublica reporter Bob Marshall speaks with host Steve Curwood about the state’s ambitious, expensive and first-of-its-kind plan to rebuild the region and the cost if they should fail. (11:25)

Place Where You Live: New Orleans, Louisiana

/ Erik IversonView the page for this story

Living on Earth is giving a voice to Orion Magazine’s long-time feature, The Place Where You Live, where essayists write about their favorite places. This week, we travel to New Orleans, Louisiana, as ecology student Erik Iverson recalls the beauty of its fragmented deltas, a land that unites a people. (04:40)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Sunita Narain, Gale Toensing, Bob

Marshall, Erik Iverson

REPORTERS: Emmett Fitzgerald, Peter Dykstra, Mary McCann

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. The latest climate summit in Peru produces the Lima Accord that for the first time requires all countries to say how they will cut emissions.

But poor developing countries with low emissions say the deal is not fair – and the industrialized world must do more.

NARAIN: If you cannot reduce your emissions, then you need to walk the talk in terms of providing the money and technology so that poor countries can grow differently.

CURWOOD: What must be done to create trust and equity among nations. Also, saving critically endangered turtles who get caught in cold water off Cape Cod, Massachusetts.

LECASSE: To our knowledge this phenomenon of a mass stranding of hypothermic sea turtles on an annual basis, this is the only place in the world that we know it happens at this scale.

CURWOOD: We'll have these stories and more this week, on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies – innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live.

India Says UN Climate Summit Fails Poor Countries

Thampanoor the transport hub of Trivandrum, capital city of Kerala in India. The monsoon and lack of planned drainage systems leads to flash floods on roads. The sight is quite common during the monsoon, in the inner city areas close to the rail & bus terminals. (Photo: indiawaterportal.org; Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. The climate summit, in Lima, Peru earlier this month, produced a major breakthrough. For the first time, all nations, developed and developing, agreed to lay out their plans to cut global warming gas emissions ahead of next year’s crucial summit in Paris. China, the world’s biggest carbon polluter, was the first major developing country to say when it will cut emissions. China’s per capita carbon emissions are 8 tons per year. The second biggest polluter, the US, produces 19 tons per person per year, but the number three emitter, India, produces less than two tons of carbon per capita. India desperately needs more power to meet its development needs, but says without help it can only afford to use more cheap, dirty coal. Joining us on the line from New Delhi is Sunita Narain, Director General of the Center for Science and the Environment in India. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Sunita.

CURWOOD: So first, in terms of the overall impact of the Lima deal, how good was it the world and the threat of disruptive climate change do you think?

NARAIN: Steve, I have to say we are very disappointed. I cannot say otherwise. The fact is, Lima needed to take tough decisions. We're at a very difficult space as far as climate change is concerned. A country like India is very vulnerable to climate change. I keep saying the monsoon in India is our true finance minister. The poor in India are being continuously hit by more and more extreme weather events. We know we need the world to take stuff action on climate change and yet at Lima many decisions that are important for the developing world was sidelined, and the tough decisions that we need for the world to review how serious it is going to be about cutting emissions at the base and the scale that is needed even that review was put aside. So what we are anticipating is a weak Paris deal.

The developing country of India is the world’s third largest CO2 polluter and its growing economy is still very much dependent upon coal energy. (Photo: Ben Beiske; Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Let's talk about in your view what was needed there, first, in terms of making a meaningful impact on the threat of climate disruption. What needed to be decided at Lima that wasn't your view decided?

NARAIN: Well, first, I think we need to make it very clear that countries need to take drastic action to reduce their emissions and even as Lima has agreed that these would be done through internationally determined actions, the fact is what we need is for countries to agree they will review those actions and make sure that the world is below 2 degrees, and that those actions also are fair even as they are ambitious, and I give you an example. The fact is that the US and China have just signed what many in the US are saying is a historic and ambitious deal to cut emissions, but when we in India have taken a look at it, we are finding that what this agreement does is to actually make sure that both countries, both big polluters, get more right to pollute, they equalize their emissions at 12 tons per capita in 2030 and more than that it means the world will not be able to keep temperatures below 2 degrees, so what Lima needed was a strong review process which would hold countries accountable, both in terms of ambition and if it is fair or not. The China/US makes sure that the two big polluters take up the biggest share of the atmosphere and leave nothing, no space, for the rest of the world to grow. That is what we need Paris to take tough actions on.

CURWOOD: So let's talk about India specifically. Under the Lima accord, for the first time, India's going to be asked to say what it will do to reduce emissions and as of 2012, your nation was the world's third largest emitter of greenhouse gases. How fair and effective is this Lima deal for India?

NARAIN: Well, I think it's very important for all countries to be part of a global agreement, so in that senses I think India needs to also put its own commitments on the table. There is no doubt that we all need to do something to combat runaway climate change, but the fact of the matter is, and I'll just give you some barebone figures just so that you understand the differences that exist. India's emissions today are 1.8 tons per person per year. China is eight tons. The US is 19 tons. In 2030, the US will be 12 tons. China will be 12 tons. India, even if it does business as usual will be four tons per person per year. So whereas India has to take steps to cut emissions, it has to do that in its own best interests because we need to become more energy efficient, we need energy security, we need to cut air pollution in our cities, but whatever India does is not going to be enough unless the big polluters in term of volume actually reduce and make space for the rest to grow.

CURWOOD: As the negotiations move forward, India's government is saying that it needs to build more coal-fired power plants. How much sense does that make in terms of climate stability?

Coffee production around the world has been adversely impacted by climate change, and developing countries such as India are less equipped than first-world countries to deal with the effects this has on food production. (Photo: Thangaraj Kumaravel; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

NARAIN: Well, it is a fact that India has a massive challenge to reach energy to very poor people. We have almost 30 million people who are still without energy in own country. 700 million people cook using dirty biomass fuel. And it cannot be acceptable for any government that you would allow your people to have no electricity not even a bulb to read under. No education as a result of it. That energy poverty is not acceptable. Now, given that situation, what choice does a country like India have? We can do coal which is much cheaper, or we can do solar, and many grids using solar, but that is still much more expensive. Now, if the word wants a country like India to leapfrog and go towards a future in which we can actually not go through the fossil fuel route, which no country in the world has done until now, and if that is the option then we will require money, we will require technology. Today, all governments in the world build grids because they are at scale, they are much cheaper, they build grids using fossil fuels, even the United States today is coal dependent, and if at all it is moving out of coal, it is moving to another fossil fuel, which is shale. It is not moving out of fossil fuel to renewable energy. The poor in the world have to provide us the options; then they have to be supported so that we can actually make the transition towards a low-carbon future.

CURWOOD: So how much would that leapfrogging cost and where would the funds come from?

NARAIN: Well, we have done some calculations for the government of India because we feel we do believe that the government of India needs to begin doing this. We are getting the government to think about a mini-grid policy for leapfrogging. Clearly it would mean first building some stations, looking at the cost, seeing what's the differential between a grid-based station and a mini-grid station. It's normally three to four times higher to supply energy using mini-grid simply because you have to literally duplicate or replicate the system for energy supply at a local level. But those plants could be grid interactive you may find a way to also reduce the costs, so I think the question is for countries like India who want to be able to leapfrog to have those options. We are certainly pushing our apartment but it would also be much easier if the rest of the world was put forward an agenda that says that climate change concerns us all, we will all reduce, the rich will reduce more so they will provide space for the poor to grow, and they will provide technology and finance so that all of us can build that new future. We are still not getting that in any climate negotiations and this time in Lima the distrust between the rich and the poor a new low where everything of concern to the developing countries, whether is it adaptation, whether it is finance, whether it is the issue loss and damage was seen to be negated by the more powerful countries, which means there is even less room for negotiations.

Sunita Narain is the Director General of The Centre for Science and Environment in India. (Photo: Courtesy of The Centre for Science and Environment)

CURWOOD: In an ideal world, Sunita Narain, how would you design a climate accord, an international climate deal?

NARAIN: I would design a climate deal, which is very similar to what we had in 1992, at the Rio Summit. I would design a deal which would make the world know that there is not that the space for growth is limited, that we all need to live within the planetary boundaries so between the two-degree target it becomes absolutely non-negotiable. We then have a space that we would need to share between nations, and that space would have to be shared on some principle of equity. Now it is very clear that you cannot ask the US to go down from 19 to two tons and therefore meet India's target today, but you can certainly ask the US and other large countries and say if you cannot reduce your emissions, then you need to walk the talk in terms of providing the money and technology so that the poor countries can grow differently. You need countries to build a climate agreement, which is built on trust between nations. You cannot therefore have a Paris deal, which is not based on principles of equity and justice.

CURWOOD: Sunita Narain is the Director General of the Center for Science and the Environment in New Delhi, India.

NARAIN: Thank you, Steve; I really enjoyed the show very much.

Related links:

- The United Nations’ Lima Climate Change Recap

- Lima COP20

- More about Sunita Narain and her work with The Centre for Science and Environment

CURWOOD: Coming up...in the rush to get home Congress passes “Christmas Tree” legislation. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems provides building technologies and supplies container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

Giveaways Turn Appropriation Bills Into Christmas Trees

Saguaro Lake in the Tonto National Forest north of Mesa, Arizona. The recent rider in the National Defense Authorization Act allows mining company Rio Tinto to dig for copper in the Tonto National Forest, an area sacred to the San Carlos Apache tribe. (Photo: Gary Wilmore; Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

U.S. Senator John McCain recently helped to pass a bill allowing a mining company access to copper located on land sacred to a First Nation tribe. (Photo: U.S. Congress)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. In a long awaited decision, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo has banned fracking for natural gas in his State, citing numerous studies that suggest risks of harmful health effects. But with no debate, a rider was slipped into the Defense Authorization Bill Congress passed on December 11th that makes it easier to get a permit to frack on federal land.

CURWOOD: There is a long tradition on Capitol Hill as Congress ends its term to deck “must pass” measures with unrelated riders—making for “Christmas tree” bills, adorned with baubles, goodies and presents for home districts. And this year the Defense Act became a Christmas tree bill with such amendments as allowing livestock to graze on the habitat of the vanishing sage grouse. One gift even puts coal in the public stocking, as among other places, a coal heritage site in West Virginia gets added to the national park system along with the ominously named River Styx in Oregon. The Defense act rider attracting perhaps the most attention is one dropped in by Republican Senator John McCain of Arizona. For the past decade Native Americans have been fighting a bid by mining giant Rio Tinto to extract copper from under a national forest in Southeast Arizona, which is sacred land for the San Carlos Apache tribe. In the name of jobs, billions for the economy and national security provided by a huge domestic source of copper, Senator McCain sponsored the rider that ignores a treaty and trades away 2,400 acres of holy land to the mining company.

Apache leap mountain is so named because it was the site where 75 Apache Indians rode their horses over cliffs rather than be taken by the U.S. Calvary. (Photo: Brent Bristol; Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Gale Toensing, a writer for the Indian Country Media Network describes this revered place, the Tonto National Forest.

TOENSING: This land, this particular land is beautiful; it’s diverse, it has ancient huge rock formations and petroglyphs, it has running streams, clean streams.

CURWOOD: And she says tribal people have fought this mine in part because of the land’s spiritual value for them and their ancestors.

TOENSING: I don't think the dominant society understands exactly what it means what a sacred place means to indigenous peoples. What’s going to happen to this land if in fact the copper mine goes through, it will be like destroying a church or a synagogue or a mosque. And we wouldn’t do that to Jews or Christians or Muslims, we just would not do that. But how come we can do it to Indians? It’s like a double whammy. It’s religious discrimination on the one hand, and because it’s religious discrimination based on race, it’s racism. It’s amazing to me that the government can do this.

New York Governor Andrew Cuomo recently announced a ban on fracking in his state, citing studies that it poses health risks. (Photo: Diana Robinson; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Toensing says the tribes can launch an appeal with the Organization of American States, and lodge protests at the United Nations.

TOENSING: So the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, one of the overriding themes of that document is that before governments do anything that would affect tribal lands or culture or their health, is that they have to get free, prior and informed consent of the tribes. There was no consultation on this whatsoever. So that’s a violation of the Declaration.

CURWOOD: Gale Toensing sees the mine land grab as a sad case of business as usual.

TOENSING: I’m always surprised by what this country does to its First Peoples, always – and I shouldn’t be, I mean there are over 400 treaties that have been violated – so I really should not be surprised when things like this happen, but I always am because I’m always hopeful that things like this won’t happen.

CURWOOD: Gale Toensing writes for the Indian Country Media Network.

Related links:

- Toensing’s “San Carlos Apache Leader Seeks Senate Defeat of Copper Mine on Sacred Land”

- Governor Andrew Cuomo bans fracking in New York State, citing health risks

- National Defense Authorization Act for FY 2015

Beyond the Headlines

Oysters harvested from California’s coast. (Photo: Min Lee; Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now we'll head off to discover what’s happening beyond the headlines. Peter Dykstra’s our guide. He publishes EHN.org, Environmental Health News, and the DailyClimate.org. He’s on the line from Conyers, Georgia, now. Hi, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve. There’s a story that’s been playing out this year that shows how honest efforts to protect the environment can still end up in a train wreck. The participants in that train wreck: A federally-protected estuary, a decades-old organic family farm business, federal regulators, and lurking in the background, world-class chefs and the Koch Brothers.

CURWOOD: Wow, that’s quite a cast of characters, how did they all come together?

DYKSTRA: Not very comfortably. The Lunny family raises grass-fed beef and prized oysters on their spread inside California’s Point Reyes National Seashore. When the feds created the Seashore in the 1960’s, they allowed some commercial entities, including the oyster operation, to stay open, but half a century later those agreements have expired and the Interior Department told the Drakes Bay Oyster Company they’d have to close up.

CURWOOD: So is there a bad guy in this episode?

DYKSTRA: I don’t think so. The Interior Department gave the Lunny family a grace period that lasted for decades, but battled them in court because they felt if they made an exception for this sustainable operation, they’d be buried in court cases from businesses maybe not quite as admirable as the Drakes Bay Oyster Company. The Lunnys fought to keep their business, drawing endorsements from the likes of Alice Waters, the renowned pro-environment sustainable chef and many other high-end chefs and foodies. They also brought in legal power for a lengthy court battle, taking some guilt-by-association heat for retaining a firm that once served the Koch Brothers, regarded by many environmentalists as villains par excellence. To me, it’s a case where nobody’s wrong: The Interior Department did what it had to do, and the Lunny family did what any business would do.

CURWOOD: But they didn’t both win.

DYKSTRA: The Lunnys are planning to open a gourmet restaurant now that the oyster farm is gone; the Feds lost a few environmentally-minded friends, the foodies lose a source of what one writer called “slimy but delicious bivalves,” but maybe the only saving grace is that a beautiful stretch of coastline called the Drakes Estero, is one step closer to being wild again.

Theo Colborn’s research helped illuminate how environmental pollutants affect body systems. Her work with what we now know are endocrine disrupters is particularly of note. (Photo: TEDx MidAtlantic; Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So a little good news, even from an environmental train wreck. What’s your next item?

DYKSTRA: Not-so-good news, on someone worthy of a tribute. Last week we paid respects to the late Martin Litton, a hero of the modern environmental movement. This week, a woman regarded by many as one of the heroes of environmental science, Theo Colborn, passed away at age 87.

CURWOOD: Yes, we’ve had Theo on the show over the years. She pioneered much of the science on the risks that some chemicals pose to our reproductive and immune systems as well as our brains.

DYKSTRA: Right, the so-called endocrine-disrupting chemicals like bisphenol-A, which is often found in plastic or metal food containers. Still a subject of some furious debate among scientists, not to mention a huge amount of industry pushback. Theo won the respect that science pioneers often do, and has been compared to Rachel Carson, and like Rachel Carson, she withstood some furious political attacks. Unlike Rachel, she lived long enough to see much of her work confirmed and vindicated by other scientists. Late in life, she turned her attention to the potential risks from the swarm of chemicals used in the fracking process.

CURWOOD: And those fracking chemicals are still shrouded in mystery. What have you brought us from the environmental history vault this week?

For 2 years, Julia Butterfly Hill lived in the canopy of a Northern California redwood tree, protecting it from being cut down. (Photo: Scott Schumacher; Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Back to Northern California: It’s hard to believe that it was fifteen years ago this week, but an activist named Julia Butterfly Hill moved out of the pad she’d lived in for the previous two years.

CURWOOD: And as I recall, literally it was some pad – a platform near the top of a Coastal Redwood tree.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, two years earlier, Julia, twenty-three years old at the time, became the center of attention when she climbed up the 180-foot tree in a symbolic protest to save it in a redwood forest scheduled to be logged. She endured some harassment and some pretty cold soggy Northern California weather, living in the tree for two years and eight days, climbing down after she’d turned twenty-five because she’d won concessions from the Pacific Lumber Company. She named the tree “Luna,” but after both she and the tree became worldwide symbols, somebody took a chainsaw to Luna, cutting about 60 percent of the way through the trunk.

CURWOOD: Why?

DYKSTRA: Because. Sorry, that’s the best answer available. Julia was making a point, so I guess somebody thought this was an appropriate counterpoint. Arborists were able to save the tree with steel braces and cables, and it’s still a mighty and symbolic redwood today instead of being somebody’s patio furniture. And Julia Butterfly Hill’s activism also continues but at ground level.

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra is the publisher of the DailyClimate.org and Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org -- thanks a lot Peter!

DYKSTRA: Thanks, Steve, talk to you soon!

CURWOOD: And there’s more at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Drakes Bay Oyster Company Settles Federal Lawsuit

- Feds evict the Lunny family from Drake’s Estero in California to protect the area.

- Remembering the late environmental hero, Theo Colborn, and her work

- Recounting Hill’s environmental activism and time in a redwood tree

- Environmental activist Julia Butterfly Hill’s personal site

Turtle Rescue

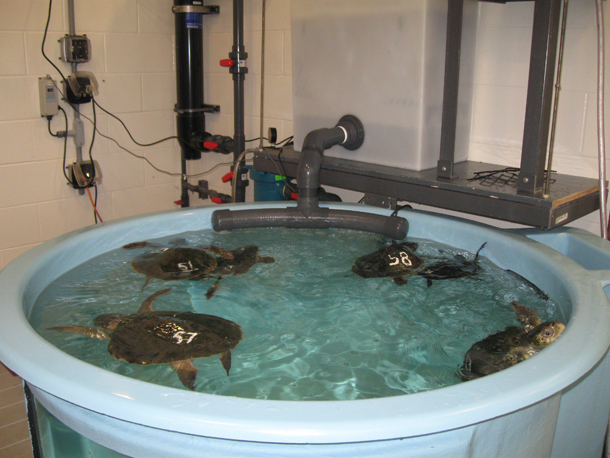

Tanks filled with turtles at the New England Aquarium’s Animal Care Center (Photo: New England Aquarium)

CURWOOD: It’s far too cold to swim in the waters off New England at the moment. But as winter comes on, chilly water regularly brings some special guests onto the beaches inside the arm of Cape Cod. Every year, sea turtles caught in the cold begin washing up on shore.

LECASSE: The north side of Cape Cod is formed like a big bucket. Turtles, when they get the instinct to swim south in the early autumn, that instinct is blocked by all this land.

CURWOOD: That’s Tony LeCasse of the New England Aquarium. For the past twenty years, the aquarium has been partnering with the Audubon Society to rescue turtles who become too cold and get stranded on the beach. Two years ago there were a record number, 242 of them, as Living on Earth's Emmett FitzGerald reported.

[Beach sounds]

FITZGERALD: Each year in November, dozens of volunteers pull on hats, zip up their parkas, and tramp the beaches of Cape Cod from Sandwich to Truro. They head out just after high tide, sometimes in the dark, following the wrackline, where seaweed marks the water’s highest point. These hardy beachcombers are looking for turtles.

LACH: We are watching for that familiar sea turtle shape, about the size of a dinner plate, but with flippers.

FITZGERALD: Michael Lach and his nine-year-old son Skyler have been volunteering with the Massachusetts Audubon Society for four years now.

Volunteer Skyler Lach, age 5, handing hypothermic turtles on the beach in Cape Cod in 2008 (photo: Michael Lach)

LACH: We asked if we could volunteer for their sea turtle rescue program and we were assigned to this very beach, Linnell Landing Beach, the next day. And what happened the next day? Who found the first turtle?

SKYLER: I did.

LACH: You did that’s right. I was really excited when we found that first one.

FITZGERALD: They comb the beach in the evening, after Skyler gets out of school. When they spot a turtle, they set it above the tide line for the Audubon staff to collect.

SKYLER: You try to find a marking, so that Audubon can see it better.

LACH: Something that really stands on the beach so that when Audubon comes down to the beach to find and pick it up they can locate it easily.

FITZGERALD: This year there have been more stranded turtles than ever before, but Skyler has only found a couple, and he's looking to add to his total.

LACH: The most we’ve found in one year is six and we’re trying to beat that record. We’ve still got five more numbers to go because we’ve already found two. If we added our last three years up I’d say that’s about 14.

[Beach sounds]

FITZGERALD: Bundled up and armed with flashlights, Skyler and his dad head off into the night.

SKYLER: Do you think we’re going to find any today?

LACH: I don’t know; we still have quite a bit of beach to walk. I think we have a pretty good chance of finding one because the northwest wind, that’s the best wind for it, but the wrackline is a bit thin.

FITZGERALD: Massachusetts Audubon delivers all of the turtles that volunteers find to the New England Aquarium’s Animal Care Center in Quincy, Massachusetts.

Numbered turtles swim in a small tank at the Animal Care Center in Quincy (photo: Michael Lach)

[Train]

FITZGERALD: The Animal Care Center is in an old brick building along the Quincy wharf. Freight trains wind between abandoned warehouses with smashed windows, and the smell of the sea is thick. Tony Lecasse let me into the Center.

[Door]

FITZGERALD: Inside the cavernous room are massive circular tanks like aboveground swimming pools. They are filled with threatened sea turtles—spotted Greens, large Loggerheads, and the most endangered sea turtle in the world, the Kemp’s Ridley.

LECASSE: The predominate species and the most important one is these little Kemp’s Ridleys. They are everywhere from dinner plate size to platter size. The juvenile sea turtles are a charcoal black with a white serrated edge and they sort of have a heart-shaped shell.

FITZGERALD: As I peer over the edge of the tank, a turtle comes up for air.

[breath noise]

FITZGERALD: Tony says, don't get too close.

A stunned loggerhead turtle being loaded into a plane bound for Georgia (Photo: New England Aquarium)

LECASSE: They’re cute little guys but you still gotta be careful with them. These guys primarily eat crabs, so if you stuck your finger in there, you might require some good stitches.

FITZGERALD: Every day, the Audubon Society delivers batches of turtles to the center in Quincy.

LECASSE: We had three days last week where we had more than 20 turtles come in at a time. To give you an idea of how unusual that is, sea turtle hospitals in Florida, might see 20 sea turtles in a season.

FITZGERALD: This hospital can hold about 100 turtles at a time. If they get more than that, they have to offload them to other facilities up and down the east coast. The center recently sent 35 turtles to Florida in a Coastguard plane. Tony says that scientists at the aquarium aren’t sure why so many turtles have stranded this year. It could be good news: the total population of turtles is recovering, and the number of hypothermic turtles is rising along with it. But climate change could be playing a role as well. Tony thinks that warm water temperatures last year might have confused the turtles, delaying their normal migration.

LECASSE: In 2011, we had water temperatures that were five and six degrees above normal for a good part of the year. And so the normal environmental cuing didn’t happen because the water was warm, and they probably thought they had more time.

FITZGERALD: When the turtles arrive at Quincy, they’re usually in pretty bad shape. They have often been floating in the bay for months, and have used up all of their fat reserves.

LECASSE: Normally there should be big rolls of fat like you’d see on a 12-month-old baby coming off the thighs. But what will happen is that you will literally see a skinny leg with sort of draped skin over it, and that just indicates how dehydrated and how emaciated a lot of these turtles are.

FITZGERALD: First the hospital staff treat each turtle for hypothermia and dehydration. Unlike warm-blooded animals, these reptiles need to be rewarmed gradually, about five degrees a day, to prevent infections. Once a turtle is back on its flippers, it can be moved into one of the big tanks with the others. The staff paint a number on the back of every turtle’s shell with white nail polish, so they can keep track of each individual.

One of the biggest challenges can be feeding.

Head veterinarian Charles Ennis treats a loggerhead at the turtle hospital in Quincy (Photo: New England Aquarium)

LECASSE: My job right now is to focus on number 28, he’s not eating.

FITZGERALD: Carla is a volunteer at the turtle hospital. She’s dangling a piece of herring in front of a small turtle with a white number 28 scrawled on its shell. Despite her efforts, 28 isn’t interested in the food.

CARLA: What we’re doing for 28 is we’re actually tube feeding him, which we don’t like to do, it’s stressful for the animal. So that’s why I need to work on him for at least a half an hour.

FITZGERALD: Feeding the turtles is an exact science, and the staff carefully monitor each individual’s food intake.

CARLA: We feed them squid and herring, and everything is weighed so we know exactly how much they’re eating.

FITZGERALD: Recent arrivals often struggle to eat solid food, and as Carla tries to coax these reluctant newcomers, healthier veterans sometimes get in the way.

CARLA: See number 55 he’s obviously hungry. So you’re trying to feed number 93 but…yes number 55 is hungry but I bet he’s already reached his capacity.

FITZGERALD: Turtle rehabilitation takes a long time. Best-case scenario, a turtle will be out of the center in a couple of months, but some will require nearly a year of treatment. When the turtles are healthy, the aquarium transports them to warmer waters to be released.

LECASSE If the turtle is ready to go in early January or February, we’ll arrange for the turtle to be flown down to Florida or Southern Georgia to be released down there. If the turtle is ready in March or April, we’ll bring that turtle down to the Carolinas. If they’re ready in the summer time we’ll release them off of the Cape or off of Martha’s Vineyard.

Stunned loggerheads being transported from Cape Cod to Quincy (Photo: Michael Lach)

FITZGERALD: The New England Aquarium and Wellfleet Audubon have been rescuing turtles for 20 years now, and they’re proud of their record.

LECASSE: If a turtle arrives alive here, it has a 90% chance of surviving and being released.

FITZGERALD: That’s thanks to biologists, veterinarians, and hundreds of committed volunteers, young and old. In the past twenty years, they have rescued, rehabilitated and released over a thousand sea turtles. For these critically endangered creatures, every effort counts. For Living on Earth, I’m Emmett FitzGerald.

CURWOOD: That number of a thousand turtles that Emmett reported had been rescued and rehabilitated over 20 years has been blown out of the water by the tally for this year. Mass Audubon volunteers have collected over a thousand turtles on Cape Cod just this fall, and they still expect some larger sea turtles to become stranded on the beaches. According to the New England Aquarium, about 97% of them are endangered Kemp’s Ridleys and so far some 640 hypothermic turtles have been warmed, treated and flown south.

As to the causes of this year’s truly historic event, so far there are only guesses. But biologists are encouraged by seeing so many Kemp’s Ridleys, given their critically endangered status.

Related links:

- New England Aquarium: Marine Animal Rescue Team Blog

- Massachusetts Audubon info about sea turtles and their rescue

- New England Aquarium: Marine Animal Rescue Program

BirdNote® Freeway Hawks

Red-tailed Hawk in flight. (Photo: Joanne Kamo)

The hawk’s breast is a light taupe color above a band of brown feathers on its belly. (Photo: Mike Hamilton)

CURWOOD: At this time of year, many people are driving on busy roads, travelling to visit family for the holidays. But the frustration of stalled traffic can offer an excellent opportunity to watch an iconic bird that feels right at home along the highway. Here’s Mary McCann with today’s BirdNote®.

BirdNote®

Freeway Hawks

[Call of Red-tailed Hawk]

MCCANN: Driving the freeway, [traffic noise] perhaps just inching along in traffic, you happen to glance up to an overhead light post where a large hawk sits in plain view. It’s brown, somewhat mottled; a small head and short tail make it appear football-shaped. It’s a Red-tailed Hawk.

[More calling]

During winter, many Red-tailed Hawks move south, joining year-round resident pairs, to feed on mice, voles, and other small mammals. The freeway’s wide center medians and mowed shoulders offer a mini-habitat of open grassland where Red-tailed Hawks watch for prey. And the light posts, telephone poles, and nearby trees offer excellent viewing perches.

The red tail of the “Red-tail” may be hard to see, since folded wings often cover it. If your view is of the bird’s front, watch for a dark bellyband across the lower part of a pale chest. If your view is of the back, try to observe a white spotted “V” in the center of the back. You’ll see the red tail when it flies.

Perhaps a bit of freeway bird watching may ease the frustration of slow traffic, so watch for this bulky football of a hawk. Once Red-tails find a successful hunting area, they return often.

I'm Mary McCann.

[Repeat calling]

The hawk has a spotted “V” pattern on its back and a red tail peeks out from beneath its wings. (Photo: Andrew Reding)

###

Written by Frances Wood

Call of the Red-tailed Hawk provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Recorded by G.A. Keller

BirdNote's theme music was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Dominic Black

© 2014 Tune In to Nature.org December 2014 Narrator: Mary McCann

http://birdnote.org/show/freeway-hawks

CURWOOD: You’ll find pictures of these chunky raptors at our website, LOE.org. Coming up...a trip to the Gulf coast, which has an ambitious and pricey plan to bring back land lost to the sea. That's just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

Related links:

- For more on Red-tailed Hawks, visit BirdNote’s page

- Listen, see and read more on the Red-tailed Hawk, its lifecycle and its history

Louisiana's Moon Shot

Louisiana’s Master Plan for the Coast includes projects like marsh creation, sediment diversion, levee, structural and shoreline protection, hydrologic restoration, and oyster reef restoration. The plan is ambitious and, if implemented on time, can restore and save some crucial wetland areas (in yellow and green), but some regions are sinking too quickly and will be sacrificed (in red). (Photo: Louisiana Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority, NASA/USGS)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Louisiana is in trouble. The Mississippi River Delta is disappearing into the Gulf of Mexico at the rate of 16 square miles a year, some of the fastest land loss on the planet. These bayou lands are crucial to the nation's fisheries as well as regional oil and gas supplies and ironically, activity by the energy industry is helping to destroy its own infrastructure. Now, industry and government have created an unprecedented plan to save and rebuild these wetlands over the next 50 years at an estimated cost of some $50 billion. Bob Marshall, a reporter for the Lens, discussed Gulf Coast land loss on Living on Earth earlier this year. And continuing with a joint project with ProPublica, he’s co-author of an analysis of the plan called “Losing Ground” Part II: Louisiana’s Moon Shot.

MARSHALL: What they're trying to do here has never been done before. They're trying to rebuild some of the wetlands that have been lost and then to maintain that against all these unknown variables such as subsidence and sea level rise and lack of funding. So in a very sense it is as ambitious in those two areas as going to the moon for the first time.

CURWOOD: So how do you rebuild wetlands? What are the methods that the engineering crowd is saying are possible to use?

MARSHALL: Well, the area was built by the river and that's the only chance to rebuild it is to get that settlement out of the river back into the sinking basins in this part of the state surrounding New Orleans. The problem is that there's only about half the sediment of the river that it had when it built this area because of all the dams north of us. And the other problem is that the land is sinking at such a rapid rate, many of these areas are already too deep and too large to be rebuilt.

Lake Hermitage’s Marsh Creation project in September. (Photo: Louisiana Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority)

CURWOOD: What are some of the specific projects associated with this plan?

MARSHALL: Well, marsh creation is the states term for what I call slurry pipelines. They dredge sediment out of the river, pump it into some of the sinking basins and just re-create these areas as a once were. Going forward they hope to do this in areas of 33,000 acres, and the diversions basically re-creating or mimicking the way the river built these deltas originally is the heart of this project because they can build land as long as the river is running, so that's why they're key. They're also doing lots of shoreline stabilization and they're rebuilding oyster reefs to help protect the shorelines from wave action. There are also different types of projects with levies. Half of this $50 billion is going to be spent on structural protection for hurricane storm surge and the cost of that has risen dramatically because the core of engineers discovered during Katrina that its design parameters for building levees didn't work, so they had to increase them and that's the cost up. They're also doing research on how different plants will be impacted - you have to have the plants to hold the soils together - what will happen to the fish and the wildlife and there are lots of variables and other concerns that they have to take into consideration such as leaving enough water in the river for shipping, not displacing communities that might be flooded by these projects and trying to tend to the concerns of fisherman and the oil gas industry.

CURWOOD: Now, what kind of time does it take to do these things?

Photos of Bay Denesse from 2004 and 2014. State and Federal governments noticed that the wetlands surrounding New Orleans were not accumulating sediment because of the fast flowing waters. In 2006, they cut into the riverbanks in order to slow waterflow and eventually sediment deposited, building 98 berms. (Photo: USGS, Digital Globe)

MARSHALL: Well, this plan is a $50 billion, 50-year plan. According to the computer projections, if everything works according to plan and is implemented on time they could actually be gaining more land then they're losing in aggregate by 2060. The problem is, they only have $50 billion. This has never been done before. In several other projections out there are big concerns such as sea level rise.

CURWOOD: So where are these projects taking place? Where exactly?

MARSHALL: New Orleans is about 90 miles from the mouth of the Mississippi River and most of these projects will be taking place in the stretch of river about 50 to 60 miles from New Orleans. The last 30 or 40 miles of the river delta is just being given up because it's sinking at such a fast rate, in some places five feet a century so there's no hope of really saving those areas, so they're trying to rebuild these wetlands that are close enough to the city and its suburbs and the smaller communities out there to provide some type of storm surge buffer as well as have a functional fishery. This is the most productive coastal fishery outside of Alaska in North America and it's based on these wetlands.

CURWOOD: So, talk to me about some of the challenges that the planners and engineers expect in this project?

MARSHALL: Say locating the sediment diversion per se, first they have to find out how much settlement and the right types of sand and sediment that are going to be in the river at a certain location. And then of course can they get it to a basin that isn't already and deep and too wide to be treated. Then they have to figure out if it's in a stretch on the river or if they take water out of the river it won't cause shoaling to the south and disrupt shipping.

Louisiana’s Barataria Barrier Island Complex Project: Pelican Island and Pass La Mer to Chaland Pass Restoration (Photo: Coastal Wetlands Planning, Protection and Restoration Act; Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, Bob, who's going to pay for this?

MARSHALL: So far the state hasn't got much help from the federal government except in the form of rebuilding the levees that they didn't build properly around New Orleans, and it collapsed during Katrina. Congress back in 2007 authorized about 27 projects that are part of this master plan, but they haven't funded any of them, and of course they haven't shown any willingness. They're waiting to see how much money the state can gain from the Deepwater Horizon settlements from BP. The state recently said they could maybe realize as much as $4 or $5 billion. If they don't find other revenue sources they figure they'll probably run up against a financial wall in about 10 years. So right now they really don't know, they're hoping that Congress will look at this and say you know this is a investment worth making because it pays for itself and its economic benefits to the country.

CURWOOD: And what about the oil and gas companies that make a lot of money with the infrastructure that's there? To what extent are they investing in protecting, well, their own infrastructure?

MARSHALL: Well, they will tell you they pay in excise taxes both to the federal government and to the state government. Those haven't been raised in some time, and the state will be getting a larger share of the offshore royalties that go exclusively to the federal government and get a larger slice beginning in 2017 to the tune of about $175 million a year depending on gas prices, of course, that fluctuates wildly, but the oil and gas companies have contributed things like PR campaigns and some individual projects, but as far as tapping into that financial resource to help pay for this, the state's political body, they want the oil and gas companies to willingly come to the conclusion that it's in their self-interest.

CURWOOD: Some would criticize this effort by saying, wait, we spend a lot of money to protect private profits with public dough.

Congress approved 27 projects in Louisiana’s Master Plan, including marsh creation around Highway 1, which is important for the oil industry, and sediment and freshwater diversions from the Mississippi to rebuild wetlands, protecting New Orleans from storm surge. (Photo: Louisiana Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority, NASA/USGS)

MARSHALL: It is a problem for the state. Other the states look here and say why should we help you if you won't help yourselves? The state's congressional delegation is also among the most aggressive in opposing climate legislation, carbon legislation, of course, this is one of the most endangered, in fact, NOAA says it's the most endangered large coastal landscape sea level rise in the country. So other states the same way to manage you know you're like someone with long cancer who wants us to help pay for the chemo but doesn't want to quit smoking. But down the road if this isn't the number one issue for the politicians in the state, I think they'll be a tremendous crisis here. There will be a storm eventually that will flood a bunch of these communities, knock out refineries. They'll expose or break lots of these pipelines and then the nation will have to deal with that. That's pretty much historically the way the country deals with these same things. We kind of move forward by crisis rather than doing proactive things.

CURWOOD: Now, the fishing industry is also big in this region so what's their role in evaluating and modifying the master restoration project plans?

MARSHALL: Well, the wetlands here, the marsh, that is really the engine that drives fish reproduction here, but, of course, you need to rebuild what you are losing because once that base of habitat gets so small, production will fall off a cliff. Problem is that the people who make money from fishing here - shrimp, finfish, crabs, oysters - have been making their fortunes on a system that has been gradually turning more saline, saltier, so the people who some of the fisherman, they don't like the idea of these big diversions being open because it will turn the water in their bays much fresher and it will displace many of their target species and so they say, "I may have to go a lot further to catch fish or oysters or crabs or there might not be any." So they're looking for ways maybe of finding funding to mitigate the economic cost to some of these people if, in fact, they would be really hurt. No one's really sure if they would be that severely impacted.

Bob Marshall is a reporter for The Lens. (Photo: Courtesy of The Lens)

CURWOOD: So, do the math for me as a projected cost of $50 billion. We know that these things end up costing a lot more the end of the day, but what is the potential loss if this does not succeed or does not even start?

MARSHALL: Well, that's hard to say, I think. You know, 50 percent of nation's refining capacities along this coast, 30 percent of its total energy supply comes in pipelines from these 4,000 rigs offshore. They would have to start looking for ways to either relay these pipelines, move the refineries, and so has this turns to open water they have to go somewhere they have to be rebuilt or re-engineered at enormous expense so it's quite the crisis that's fast approaching. People always ask me are you optimistic this will get done? I'm optimistic it could be done, but I think the human element is much more...and the political element is much more of a variable that could kill the effort than overcoming the science and engineering part of it. But if they don't succeed here then about a million people have to find new places to live and one of the nations key energy corridors could be disrupted, if not shut down, and the port that serves 31 states would be in serious trouble. So, you know the old cliché failure is not an option, and the other thing here is that there's a deadline. If they don't get this done and 50 to 60 years they can't get it done and it will just be this massive environmental evacuation, immigration from this part of the state north finding homes for people and industries.

CURWOOD: Bob Marshall is a reporter for The Lens. Thank you so much.

MARSHALL: Thank you.

Related links:

- ProPublica The Lens’ Losing Ground Part II: “Louisiana’s Moon Shot” co-authored by Bob Marshall includes interactives of the plan’s current projects and possible outcomes

- Louisiana’s Comprehensive Master Plan for a Sustainable Coast

- ProPublica The Lens’ Losing Ground Part I

- Our previous interview with Bob Marshall regarding Louisiana’s disappearing coasts

Place Where You Live: New Orleans, Louisiana

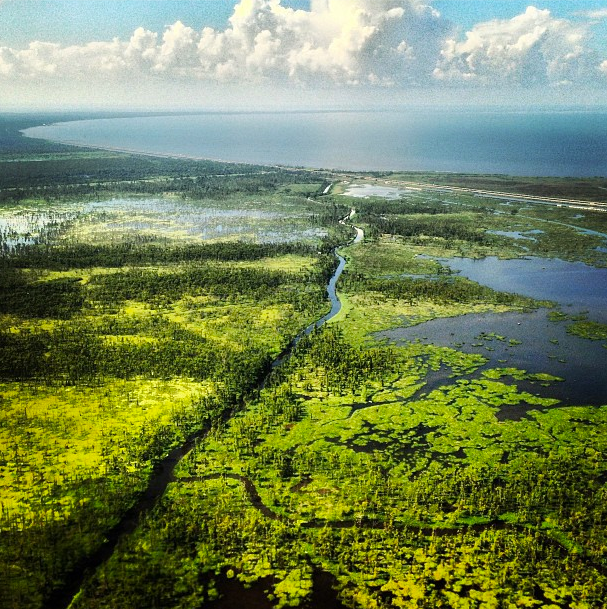

The Mississippi River north of New Orleans. (Photo: Erik Iverson; Instagram)

CURWOOD: Now another in the occasional Living on Earth/Orion Magazine collaboration, “The Place Where You Live.” Orion invites readers to put their homes on a map and submit essays to the magazine’s website, and we give them a voice.

[MUSIC: Edward Sharpe and The Magnetic Zeroes “Home” from Edward Sharpe and The Magnetic Zeroes (Rough Trade Records 2009)]

CURWOOD: We’re staying on the Gulf coast at a place dear to many people.

[MUSIC: Jelly Roll Morton, The Crave]

IVERSON: IVERSON: My name is Erik Iverson. I’m an undergraduate at Tulane University, studying ecology and evolutionary biology. I’m from the San Francisco Bay area originally, but for the last four years, I’ve made New Orleans my home. And I love it very much.

Cypress swamps ring Lake Ponchartrain and help protect communities from storm surges. (Photo: Erik Iverson; Instagram)

IVERSON: New Orleans really is sort of an island because it is isolated on all sides by water. On the north, there’s Lake Pontchartrain. To the south is the Mississippi River and there’s wetland on the east and west. You find that the land in this area is kind of a precious commodity, and so the shapes of the towns and cities mirror the shapes of the ridges in the landscape where people could find enough dry land to build on. We get around by causeway a lot. Most of the roads leading out of New Orleans are elevated up out of the swamps. You may feel like you’re driving on solid land, but that concrete is up out of the water to tell you that it’s actually a bridge.

On drier land, pines grow, like this grove in the De Soto National Forest, MS. (Photo: Erik Iverson; Instagram)

IVERSON: Land loss is a humongous issue. It’s quite sad, actually, the way things are going down there. Thankfully the state is implementing this Coastal Master Plan to attempt to reverse land loss by the year 2050, and ultimately have zero net land loss, start gaining land again. But, with the Coastal Master Plan, the land that is going to be added is not going to be in the same place as the land that’s lost, so the shape of the state is changing all the time. And by 2050, when you look at that boot of Louisiana, it’s not going to look like that anymore; you’re going to see something very different.

This is the place where I live: New Orleans, Louisiana.

The Place Where You Live

The marshes in the Barataria basin slip away with each passing year. (Photo: Erik Iverson; Instagram)

"A sense of place is the sixth sense, an internal compass and map made by memory and spatial perception together.” —Rebecca Solnit

New Orleans, Louisiana

Posted by Erik Iverson | September 8, 2014

IVERSON: Those who find comfort in the sweaty arms of New Orleans probably don’t fantasize much about life outside the levees. We are, in many ways, an island: an urban island pulled up from the swamps, a politically blue island in a sea of red, the northernmost outpost of the Caribbean’s cultural archipelago. Like all islands we are surrounded by water, and those waters rise menacingly with each passing year. It’s a refuge for folks of all kinds, but when I am tired of potholes, people, culture, and city-business, I look at those levee-walls, blind to the river beyond for our own unbearable flatness, and I feel trapped.

A shrimp boat heads to sea north of Venice, LA. (Photo: Erik Iverson; Instagram)

IVERSON: This island is, graciously, close to the mainland. Whenever I can I load up my little Ford with its awkward California plates and venture over bridges into Louisiana or Mississippi. Its not because I don’t love New Orleans—far from it—but because I love it enough to know when we should spend time apart.

The reach of the city is long. We’re in the De Soto, a wilderness of piney uplands and jungle-like bottomland hardwoods that’s been left to itself longer than the surrounding paper forests. In a black-water creek, shallow, sandy, old, and rich with tannins, we spend a naked afternoon with some new friends. We needn’t be worried; the threat of rain drove away any prudish locals, though its been nothing but beautiful for us. We all seem to have sensed that a rainy weekend in the woods was preferable to a rainy weekend in the city.

IVERSON: I could tell they were from New Orleans before we exchanged a word, and, once we spoke, I knew exactly which neighborhood. Geography is essential in such a flat space; we have only two dimensions to orient ourselves. Like all islanders we aggregate when set adrift, forming new islands on old connections to place. Wherever I go I find New Orleanians, or rather, we find each other, and friendship comes organically. Like a bottle of sand we carry this island with us, a reminder, a keepsake, a catalyst.

The Mississippi River, seen from New Orleans, LA. (Photo: Erik Iverson; Instagram)

CURWOOD: Erik Iverson, from New Orleans, Louisiana. And tell us about "The Place Where You Live." You can find details of our collaboration with Orion magazine – and learn how you can submit your own essay at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- How to contribute to Orion Magazine’s The Place Where You Live

- Orion Magazine

- Past editions of “The Place Where You Live” on Living on Earth

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth